Features

Inauspicious start and getting into my stride at the Victorian Bar

Excerpted from a Life in the Law by Nimal Wikramanayake

I drove into work on Monday, 13 October 1972 trembling with excitement. I walked into Owen Dixon Chambers and took the lift up to the third floor to DB’s chambers. DB took me next door and introduced me to a lady barrister, Lyn Opas, in a little dog-box next to his chambers. Next he took me across the corridor and introduced me to a young barrister by the name of John Coldrey. Coldrey had a criminal practice and was later to become the Director of Public Prosecutions, and still later he was appointed to the Supreme Court. Coldrey asked whether I would like to have a cup of coffee and suggested we go up to the lounge on the thirteenth floor.

He was a delightful man with an impish sense of humour. As we walked into the lounge the buzz of conversation suddenly stopped and all the barristers in that room turned around to stare at me. Not a word was spoken as John went up to the servery and ordered two cups of coffee. We sat down and the conversation resumed.

A number of barristers clustered around me and asked me what I was doing there. I told them that I had come to the Victorian Bar to give it some colour. This little quip of mine elicited guffaws of laughter. Coldrey and I then went back down to the third floor and I sat at my little desk. Peter Heerey had arranged for me to sign the Bar Roll on October 26 so that I was now a member of the educated unemployed for the next fortnight.

In the first few weeks, almost every single barrister I saw stopped me to ask me who I was and what I was doing in Owen Dixon Chambers. My stock reply was that I had come to the Bar to give it some colour, but I had to stop my little quip because it elicited some rather snide racist comments.

In the meantime, I was of considerable assistance to DB; having been an advocate/barrister for twelve years, I was extremely skilled in drafting legal documents. I whiled away my time drawing Statements of Claim in the Supreme Court, Particulars of Demand in the County Court, interrogatories and answers to interrogatories.

Mr Nkrumah

November was soon upon me and I sat at my desk for the first two weeks, looking longingly at my telephone and waiting for it to ring. When it did ring suddenly it was my former neighbour, Peter Allaway. While I was a solicitor, we rented a house in Jordan Street, Malvern, but once I made my decision to go to the Bar we moved into a small flat in Myamin Street, Armadale. Peter had been my neighbour in Jordan Street. He had a motor car collision case, or what is commonly called a “crash-and-bash” case.

Peter’s client was IPEC, a large firm of removalists. One of its drivers had been involved in a three-car collision and Peter retained me to appear for the driver, who was the second defendant in the Magistrates’ Court at Williamstown. Peter duly delivered the brief and I spent many an hour preparing it. I would show these young Australian barristers my mettle.

I got up the next morning and left home at 8.30 am for Williamstown. My knowledge of Australian roads was extremely limited as I had been but a year in Melbourne. I had pored over my Gregory’s Street Directory the previous night. Now I wandered up and down the Nepean highway for a couple of hours and was hopelessly lost. I finally arrived at a ferry and went across on it, arriving at the Williamstown Court at 11 am. I rushed into the Magistrates’ Court and learned to my chagrin that my case had been called and was about to be heard. I rushed in and took my seat at the Bar table when two young barristers moved across and sat on either side of me.

I was nonplussed when the first one got up and marked his appearance. He was Peter Rattray and the second was John Tebbutt. After they had marked their appearance I marked my appearance. I had shortened my name to Wikrama when I went to the Bar, and the magistrate, Harry Boarder, asked me to spell my name. I said: W-I-K-R-A-M-A. The magistrate was a beady-eyed, pompous man who looked down at me and said, “Carry on, Mr Nkrumah” (Nkrumah was then the president of Ghana and I can assure you that I bore no resemblance to him.) I gently told the magistrate that my name was Wikrama and not Nkrumah.

His reply was, “That’s alright. Carry on, Mr Nkrumah.” This was my first experience of blatant racism in Australia. Rattray put his client in the box, led his evidence-in-chief, and counsel for the first defendant cross-examined him. I then got up to cross-examine to find that Rattray and Tebbutt each in turn objected to every question I put. Most of my questions were clearly admissible but the magistrate, Harry Boarder, joined in the exchanges. He upheld every single objection, yet most of the objections were completely and utterly frivolous.

The same thing happened when John Tebbutt put his client in the box. My cross-examination was interrupted by Rattray and Tebbutt’s objections. When I put my client in the witness box, these two young heroes objected to every single question I put. I was completely shattered at the end of this experience.

Of course, you can guess the inevitable. Rattray won 100 per cent, John Tebbutt’s client was exonerated and in addition received compensation from my client for his damage. Furthermore, my client was made liable to pay two sets of damages and two sets of costs. I was mortified. I walked out of court and told both these heroes that this would never happen to me again – and it never did.

I returned to my chambers and gave Peter Allaway the bad news. He was furious. I was about to have my dinner that evening when Peter burst into our little flat in Armadale. He was screaming and yelling at the top of his voice, and was uncontrollable. He told me that because of my incompetence and stupidity, he had lost an exceptionally good client, as IPEC was taking all its business away from him.

Explanations were useless, as Allaway refused to believe his client could in any way have been negligent. He promised me that he would never brief me again and that I should leave the Bar, as I was hopelessly and utterly incompetent. He stormed out of the flat leaving me speechless. What an inglorious beginning!

My brief fee in the Allaway case was $46 – my only income for November 1972 – an inauspicious beginning.

The Christmas vacation

The Christmas vacation was soon upon me as the courts, in my case the Magistrates’ Court, was closed for two weeks. DB had given me about forty briefs to work on during the summer vacation. I spent the next two weeks diligently working my way through them as Anna Maria had to work through January.

In that month, DB invited us home for dinner. We took chocolates for his four children. The youngest, little Willie, was two years old. He finished eating his slab of chocolate and stood beside me while I was having dinner. He kept staring at my hand which was resting on the arm of my chair. He suddenly leant forward, grabbed my hand and bit it, obviously thinking it was another piece of chocolate. I gave a loud yell and little Willie disappeared.

I returned to work in the first week of January and sat there twiddling my thumbs, as no solicitors delivered briefs to Gamin’s list. I worked through DB’s pleadings and gave my completed work to him when he returned to work on February 1. I got plenty of thanks but no money.The next few months were uneventful, save for the fact that volume one of Williams found its way back to my desk. I was writing in about $400 a month until the time came for me to end my reading.There were about 420 barristers at the Bar at that time and rooms were rare as hens’ teeth. I remember my friends, Peter Buchanan (now the late Mr Justice Buchanan of the Court of Appeal) and Clive Rosen sharing a little cubicle on the first floor in Owen Dixon Chambers.My friend Michael Croyle and I had coffee early in the month of April and he proudly told me that he had obtained a room in Equity Chambers. This is where Sir Eugene (“Pat”) Gorman comes into my story.

Sir Eugene Gorman

In 1952, Dad had brought us out to Australia on a holiday. His friends were aghast because Australia was regarded, as Ava Gardner once said, as “the end of the world” Dad said that he would like to see a place where no one else had been to, so we travelled to Australia on the Neptunia, a Lloyd Triestine vessel. It was a small boat, some 12,000 tonnes in weight, and it rolled badly. We spent three weeks in Melbourne because the Neptunia was to go on to Sydney, be refurbished, and return three weeks later. But the voyage was delightful, as we traveled first class and the service on board first class was unbelievable, second to none.Dad was vice-chairman of the Ceylon Bar Council. When he came to Australia he met two distinguished lawyers, Pat Gorman and Monahan KC, later Mr Justice Monahan of the Supreme Court of Victoria.

Ceylon was one of the richest countries in the world at that time. It was selling its rubber to China as no other country was trading with China. Tea was extremely expensive, costing one English pound for a pound of tea until our prime minister ruined the market in 1954.The stupid man went to England and when he expressed surprise at the price of tea, which he said should not have been one English pound, the price of tea fell to two shillings and sixpence a pound.

In addition, when malaria was virtually eradicated, the population started increasing in leaps and bounds. The final straw came when the government granted free education, which meant Ceylon became a third-world country. I refer to this debacle because Monahan KC was horrified at my father’s fees. He was charging fifty English guineas a day while Monahan was charging fifteen Australian pounds a day.

Pat Gorman and Dad became good friends and when he discovered that Dad was on the committee of the Ceylon Turf Club, he took him to the three race courses in Melbourne. They kept up their friendship over the years. When I decided to emigrate to Australia, Dad wrote to Pat Gorman and told him that I was coming to Australia.

Sir Eugene Gorman (known as Pat) was one of the great advocates at the Victorian Bar. He was born in 1892 and had a large and a lucrative practice. His boast was that he intended retiring at the age of fifty, but the war intervened so he went off to war and retired immediately after. I believe he was a general in the Australian Army and ran the race course in Egypt during the war.

He had large salubrious chambers on the third floor of Equity Chambers, and a sign on his door read: Nothing matters half as much in life, as you think it does.Whenever I went to see Pat Gorman he was seated behind his large desk in his large room puffing on a large Cuban cigar. He would greet me with great affection, but within a few minutes would start moaning about how badly off and poor he was. For the life of me I was at a loss to understand why his conversation always started off with his poor financial situation.

It was only after he died that the penny dropped. Gorman thought that every time I visited him I was coming there to “touch him for a load”. When I decided to go to the Bar, he invited two of his friends who were senior partners in two big city firms to dinner with me. Suffice it to say I never got a brief from them.He always threw a large party every Christmas and he invited me to his party when I was reading with DB in 1972. These parties were magnificent affairs, with champagne flowing freely, oysters and the rest.

Anyway, I decided to see Pat Gorman about getting a room in Equity Chambers. I remember going to see him one afternoon in April 1973. His secretary, Pam Nicholson, ushered me into his room and he greeted me with his customary warmth. I told him that there was a room falling vacant in Equity Chambers and asked whether it would be possible for me to have it.

He picked up the phone and dialled Sir James Tate, who then handled accommodation at the bar. Pat Gorman said, “James, I have young Nimal Wikramanayake here with me. I believe there is a room going in Equity Chambers on the second floor. I want you to give it to him” I did not hear what Sir James said but Pat put the phone down, looked up at me and said: “Sonny, the room is yours” This was, I might say with some modesty, the only underhand thing I have ever done in my life. To this day Michael Croyle does not know how he lost his room. Mick died after I began this writing.

I would like to tell you about an interesting incident that happened during the final months of my reading period. It is slightly risque and un-Australian but still amusing. DB decided to take me for a drink to his club, the Victorian Club. It was in Queen Street and the subject of the “Great Bookie Robbery” a few years later. We got there shortly after five pm and joined a large group of about 15 people.

There was a short, florid Australian who appeared to take umbrage at my presence for he started relating racist Indian jokes, obviously under the impression that I was Indian. When he had finished relating his second anti-Indian joke, I asked the group whether I could have the floor and tell them a joke about the “New Australian”. They all agreed to let me have the floor, save for the florid Australian.

I told them that an Italian recently had been granted citizenship. He was excited about it and that evening he went to a pub close to his home, something he had never done before. He asked the bartender for an empty glass and then urinated into it and drank its contents. This created great interest among the members in the pub. He then left the pub with the members trailing behind him. He went back home and entered his garden through a side-gate, went to his fowl run and started choking a few of his hens to death. He then opened the back gate and went into a paddock where a cow was grazing peacefully. He went up to the cow, picked up its tail and put his ear to his rectum. At this stage the police were contacted and he was taken before the authorities for certification as being mentally unsound.

He was furious and said, “Why you arrest me? Me new Australian. Me go the pub, me drinks da piss, me screws da birds and then me listen to da bull-shit.’ This little anecdote was greeted with roars of laughter and the racist gentleman put his drink down and disappeared. I shouted to him to come back as I had a lot more jokes.

Features

Development must mean human development

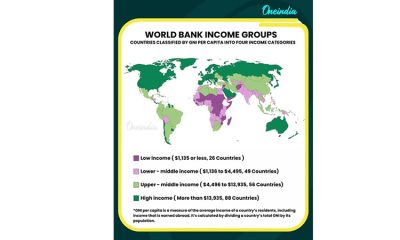

Neo-liberal economists assess economic development using parameters like GDP growth, inflation rate, interest rates, debt/GDP ratio and such and recommend measures to improve these expecting a resultant improvement in poverty rates, employment and household income, but this seldom happens as revealed by increasing inequality, decline in real incomes, malnutrition and school dropouts. Increased GDP doesn’t always translate into improved living standards or reduced poverty if benefits aren’t shared.

Quality of life has to be measured in terms of health, education, morals, satisfying employment and cultural activity. Further the society and environment of humans must be conducive for achieving a satisfactory quality of life. Present development models designed to fit the global neoliberalism focus on the development of the economy often at the expense of poor lives, labour, environment, morals and culture.

Human Development

Development must mean human development because true progress focuses on expanding people’s freedoms, capabilities (health, education, skills), and choices, rather than just economic growth (GDP). It’s a people-centered process that ensures individuals can lead fulfilling, productive lives, requiring inclusive policies, social equity, environmental stewardship, and empowerment for meaningful participation in society, moving beyond mere income increases to holistic well-being and human potential. True development addresses social, cultural, political, and environmental aspects alongside economic progress for sustainable well-being. Development, at its core, is about the expansion of human potential and rights, ensuring everyone has a chance to achieve their full potential.

It’s a transformative process that prioritizes people, their freedoms, and their ability to shape their own lives, making it a fundamental human right and the true measure of societal progress. Investing in education, healthcare, and culture has a powerful multiplier effect on families and societies

If Sri Lanka is taken as an example, over the 70 years since independence economic, social, health and education disparity between the rich and the poor has increased. Poverty rate at present is 24%, malnutrition is hovering around 15%, school dropout rates are alarmingly high, environment and climate vulnerability as experienced recently is frightening, regarding morals less spoken the better, and debt pressure is uncontrollable despite IMF.

Global Scene

Global scene is no better with inequality rising even in countries like the US, Europe, except in China and Vietnam. Poverty rate in the US is 11% and in Europe 12%. In contrast, China and Vietnam, which are not wholly linked to the neo-liberal economic system, have poverty rates below 1% and 4%, respectively. India still has a substantial number below an income level of USD 3.65 per day amounting to about 40% though extreme poverty (income below USD 2.5 a day) has reduced to about 2%. The upper 10% in the countries with more than 10% poverty own more than 60% of the wealth. One may argue that poverty cannot be totally eliminated, however it needs only 0.3% of the global GDP to eradicate poverty of people living below an income level of USD 2.5 per day. The rich don’t seem to care about this sad situation.

Wealth inequality in Sri Lanka is severe, with recent UNDP reports (2023) placing it among the top five most unequal countries in Asia-Pacific, where the richest 1% own about 31% of wealth, while the poorest 50% own less than 4%; this concentration of assets, coupled with the recent economic crisis, exacerbates deep gaps between rich and poor. Income gaps are stark, with Colombo district seeing the richest group hold over 72% of household income, compared to lower-income areas. Despite easing inflation and reasonable GDP growth, food prices more than doubled between 2021 and 2024, contributing to elevated malnutrition and food insecurity and real wages remain below their 2019 levels.

These facts and figures clearly show that neo-liberal policies have failed in human development in Sri Lanka as well as all countries in the grip of neoliberalism. A quarter of the population is in decline in health, education, real income, employment, morals, culture and all other good aspects of living. On the other hand, in countries which are not bound by the neo-liberal global system poor people are not on the decline but are well incorporated in the inclusive system of governance. Martin Jacques a British journalist and author of When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order, has lauded the Chinese model for its economic success and argued that it represents a distinct, effective approach to governance.

Broad-based investment

Sourabh Gupta, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Institute for China-America Studies, has praised China’s governance model for its “broad-based” investment in people, including healthcare, education, and infrastructure. China’s governance model prioritizes stability and long-term policy continuity, positioning it as an adaptable and effective system in certain non-Western contexts. The model’s emphasis on performance-based governance, continuous public engagement through consultative mechanisms, and controlled media strategies presents a unique approach that aligns well with the developmental needs of some emerging economies (M Y Abesha, B F Kebede, 2024). Similarly praise for the Vietnamese system of government, often centers on its political stability, the success of its Đổi Mới (Renovation) economic reforms, and its ability to maintain rapid, sustained growth.

In the grip of neo-liberalism

It is not that the countries caught in the grip of neo-liberalism have not made special attempts to improve the lot of the poor and it is also true that there had been significant improvements but the gains are not stable, and are very much vulnerable to external vagaries such as Trump and his tariffs, climate disasters, etc. as recently observed in Sri Lanka where poverty jumped from 14% to 24%. This is the fault of the system we are caught in and not so much in the intentions or competence of governments. Having said that, the onus however, is on the rulers to try and develop alternate systems that address poverty and human development.

The greed dependent, consumerism driven, profit motivated neo-liberal systems focus on capital accumulation and expect benefits to trickle down to the poor, but as seen so often the amounts that trickle down are woefully inadequate to solve poverty. This is why the national poverty statistics show that the richest country in the world, the US has 11% poor people while China has almost none. This is despite continuous effort by the US government to solve and overcome the problem.

This predicament is common to all poor countries in the global south, they are all in the neo-liberal trap. Individual countries cannot escape even if they want to. If they attempt it what could happen could be seen when one looks around. Vietnam had to pay a heavy price to defeat two imperial powers and fortunately they had Ho Chi Minh which made all the difference. Iraq, Libya, Syria, Venezuela lost but their people may still harbour anti-imperial fervour and one day may rise up.

Need for new World Order

Instead of waiting for that day what has to be done, as I have repeatedly said in my earlier letters in these columns, is for the global south to join forces and develop a new world order based on an economic system that would emphasize on human development rather than GDP, which would have the capacity to face up to the might of imperialism. Together they would be a force that could fearlessly face up to the hegemony of the global north. The new world order must jettison the export led economic model and instead make self- sufficiency in each country the common goal. Instead of competition between these countries to produce for export to the global north, there should be cooperation to help each other to achieve self-sufficiency and human development. If countries of the global south become self-sufficient in essential needs neo-liberalism will be eradicated and human development would take precedence.

by N. A. de S. Amaratunga

Features

The Separation of Powers and the Independence of the Judiciary

Checks and Balances in the Present Constitution

Moreover, the recent ruling given by the Speaker in Parliament on January 9, 2026, on the Opposition Motion to appoint a Select Committee to review recent appointments made by the JSC to the Judiciary further buttresses the explicit recognition of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary. The Speaker reiterated the commitment of Parliament to the doctrine of the SOP and refused the Motion on the basis inter alia that Parliament was not hierarchically superior to the Judiciary and cannot be permitted to control the judiciary by creating an oversight mechanism with regard to the JSC.

Professor G.L. Peiris (Prof. GLP) in a speech delivered on December 12, 2025 at the International Research Conference at the Faculty of Law, University of Colombo published in The Island of December 15, 2025 under the caption “Presidential authority in times of emergency – A contemporary appraisal” has critiqued the majority judgment of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka in Ambika Sathkunanathan V. A.G. on the declaration of emergency by Ranil Wickremesinghe as Acting President on July17, 2022 in response to the Aragalaya. The majority held that Wickremasinghe had violated the Fundamental Rights of the people by a Declaration of a State of Emergency. The author was to attend this event but was unable to do so due to a professional commitment out of Colombo.

After citing authority from several foreign jurisdictions in support of his view of judicial deference to the Executive on matters relating to an Emergency, he advances as one of the grounds as to why the majority were wrong in the Sri Lankan context is that the predisposition to judicial deference is reinforced by a firmly entrenched constitutional norm – “a foundational principle of our public law is the vesting of judicial power not in the courts but in parliament, which exercises judicial power through the instrument of the courts. This is made explicit by Article 4(c) of the constitution which provides “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts, tribunals and institutions created and established, or recognised by the Constitution, or created and established by law, except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law” . Prof GLP opines that the majority judgment constitutes “judicial overreach which has many undesirable consequences” including “traducing constitutional traditions; subverting the specific model of separation of powers reflected in our Constitution”.

Prof. GLP, is in effect advancing the view that the Sri Lankan Courts in the present constitutional framework of the Second Republican Constitution 1978 are subservient to the Executive or Parliament.

This view of Prof. GLP is with respect, wrong on both constitutional principle and policy. There are no constitutional restraints on the judicial review of executive action in relation to declarations of emergency. Self-imposed judicial restraint may well constitute an abdication of judicial responsibility.

Unlike the Independence Constitution where a Separation of Powers (SOP) was found by judicial interpretation with the concomitant judicial power to even strike down post enacted legislation, the 1st Republican Constitution of 1972 explicitly did away with the concept of an SOP and instead whilst vesting sovereignty in the people, nevertheless made the National State Assembly the supreme instrument of state power exercising the Executive, Legislative and Judicial power of the people (vide Article 5). Resultantly the judicial review of enacted legislation was expressly done away with and instead pre-enactment review of a Bill tabled in Parliament by a Constitutional Court was provided for.

Indisputably, this fundamental departure introduced by the First Republican Constitution was a direct response to the Queen V. Liyanage and the other judicial power cases where the Courts expressly recognised an SOP and the jurisdiction to even review the constitutionality of post enacted legislation.

But this doctrine of the abolishing of the SOP was subsequently abandoned, and one of the significant and welcome departures introduced by the Second Republican Constitution of 1978 was the explicit reintroduction into our constitutional framework of the principle of an SOP. This is made explicit by Articles 3 and 4 of the Constitution which vests Sovereignty in the people but proceeds to delineate how that sovereignty is exercised in terms of the trichotomy of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers and the further recognition of franchise and Fundamental Rights as also integral components of the sovereignty of the people.

Although the twin principles introduced in 1972 of a constitutional bar on the post-enactment review of legislation was retained together with the pre-enactment review of legislation in the present 1978 Constitution, nevertheless the reintroduction of the SOP which guarantees the independence of the Judiciary is a fundamental feature of the present Constitution.

Although Article 4(c) of the present Constitution does state that “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts … recognised by the Constitution … except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its Members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law”, nevertheless there is a cursus curiae (practice of the court) of judicial authority by the Sri Lankan superior Courts that have recognised both the concepts of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary from Executive or Legislative encroachment.

Leading cases which have recognized an SOP include Premachandra V. Monty Jayawickrema (1994) 2 SLR 90 (SC) and the Supreme Court Determination on the 19th Amendment to the Constitution (2002) in which the author appeared as Junior Counsel to the late Deshamanya H.L. de Silva P.C. The Supreme Court has recognised that the independence of the Judiciary is an intrinsic component of the present Constitution in several cases including the Court’s Determination on the Industrial Disputes Act (Special Provisions) Bill 2022. In fact, a more explicit pronouncement was made in Hewamanne V. De Silva where the Supreme Court held that judicial power vested solely and exclusively in the Judiciary (1983) 1 SLR 1 at 20.

Moreover, the explicit vesting in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka under Articles 125 and 126 of the exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and in respect of Fundamental Rights underscores the preeminent role of the Judiciary in our constitutional framework. Foundational principle of the present Constitution as recognized by our Courts include the Rule of Law, power is a trust, and there are no unfettered discretion in public law. Regrettably, Prof. GLP assails these welcome advances made in our public law jurisprudence.

In our constitutional setting of checks and balances and judicial oversight it is the function of the Judiciary to review the legality of Executive action, including matters relating to the declaration of a State of Emergency and Emergency Regulations. The duty of interpreting an Act of Parliament is a function of Courts and not of Parliament (Court of Appeal in C.W.C. V. Superintendent, Beragala Estates 76 NLR 1). The author cited this decision to the Supreme Court in challenging the Inland Revenue Bill introduced by the late Mangala Samaraweera. That Court reiterated this principle and agreeing with the author, ordered a referendum on a particular Clause.

Even in the pre-independence period up to 1948, when vide powers were conferred on the Governor who exercised Executive authority, the Courts have unequivocally reviewed the legality of executive action as manifest by the significant decision of the Supreme Court in 1937 in “In Re. Mark Anthony Lester Bracegirdle“, where the executive act of the Governor of arrest and deportation of Bracegirdle to Australia was reviewed by the Supreme Court and quashed. This decision was a striking assertion of judicial independence and is the first significant judicial review of executive action.

Moreover, the recent ruling given by the Speaker in Parliament on January 9, 2026, on the Opposition Motion to appoint a Select Committee to review recent appointments made by the JSC to the Judiciary further buttresses the explicit recognition of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary. The Speaker reiterated the commitment of Parliament to the doctrine of the SOP and refused the Motion on the basis inter alia that Parliament was not hierarchically superior to the Judiciary and cannot be permitted to control the judiciary by creating an oversight mechanism with regard to the JSC.

(The author is a President’s Counsel and a Professor of Law)

By Nigel Hatch1

Features

Trump’s Interregnum

Trump is full of surprises; he is both leader and entertainer. Nearly nine hours into a long flight, a journey that had to U-turn over technical issues and embark on a new flight, Trump came straight to the Davos stage and spoke for nearly two hours without a sip of water. What he spoke about in Davos is another issue, but the way he stands and talks is unique in this 79-year-old man who is defining the world for the worse. Now Trump comes up with the Board of Peace, a ticket to membership that demands a one-billion-dollar entrance fee for permanent participation. It works, for how long nobody knows, but as long as Trump is there it might. Look at how many Muslim-majority and wealthy countries accepted: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Pakistan, Indonesia, and the United Arab Emirates are ready to be on board. Around 25–30 countries reportedly have already expressed the willingness to join.

The most interesting question, and one rarely asked by those who speak about Donald J. Trump, is how much he has earned during the first year of his second term. Liberal Democrats, authoritarian socialists, non-aligned misled-path walkers hail and hate him, but few look at the financial outcome of his politics. His wealth has increased by about three billion dollars, largely due to the crypto economy, which is why he pardoned the founder of Binance, the China-born Changpeng Zhao. “To be rich like hell,” is what Trump wanted. To fault line liberal democracy, Trump is the perfect example. What Trump is doing — dismantling the old façade of liberal democracy at the very moment it can no longer survive — is, in a way, a greater contribution to the West. But I still respect the West, because the West still has a handful of genuine scholars who do not dare to look in the mirror and accept the havoc their leaders created in the name of humanity.

Democracy in the Arab world was dismantled by the West. You may be surprised, but that is the fact. Elizabeth Thompson of American University, in her book How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs, meticulously details how democracy was stolen from the Arabs. “No ruler, no matter how exalted, stood above the will of the nation,” she quotes Arab constitutional writing, adding that “the people are the source of all authority.” These are not the words of European revolutionaries, nor of post-war liberal philosophers; they were spoken, written and enacted in Syria in 1919–1920 by Arab parliamentarians, Islamic reformers and constitutionalists who believed democracy to be a universal right, not a Western possession. Members of the Syrian Arab Congress in Damascus, the elected assembly that drafted a democratic constitution declaring popular sovereignty — were dissolved by French colonial forces. That was the past; now, with the Board of Peace, the old remnants return in a new form.

Trump got one thing very clear among many others: Western liberal ideology is nothing but sophisticated doublespeak dressed in various forms. They go to West Asia, which they named the Middle East, and bomb Arabs; then they go to Myanmar and other places to protect Muslims from Buddhists. They go to Africa to “contribute” to livelihoods, while generations of people were ripped from their homeland, taken as slaves and sold.

How can Gramsci, whose 135th birth anniversary fell this week on 22 January, help us escape the present social-political quagmire? Gramsci was writing in prison under Mussolini’s fascist regime. He produced a body of work that is neither a manifesto nor a programme, but a theory of power that understands domination not only as coercion but as culture, civil society and the way people perceive their world. In the Prison Notebooks he wrote, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old world is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid phenomena appear.” This is not a metaphor. Gramsci was identifying the structural limbo that occurs when foundational certainties collapse but no viable alternative has yet emerged.

The relevance of this insight today cannot be overstated. We are living through overlapping crises: environmental collapse, fragmentation of political consensus, erosion of trust in institutions, the acceleration of automation and algorithmic governance that replaces judgment with calculation, and the rise of leaders who treat geopolitics as purely transactional. Slavoj Žižek, in his column last year, reminded us that the crisis is not temporary. The assumption that history’s forward momentum will automatically yield a better future is a dangerous delusion. Instead, the present is a battlefield where what we thought would be the new may itself contain the seeds of degeneration. Trump’s Board of Peace, with its one-billion-dollar gatekeeping model, embodies this condition: it claims to address global violence yet operates on transactional logic, prioritizing wealth over justice and promising reconstruction without clear mechanisms of accountability or inclusion beyond those with money.

Gramsci’s critique helps us see this for what it is: not a corrective to global disorder, but a reenactment of elite domination under a new mechanism. Gramsci did not believe domination could be maintained by force alone; he argued that in advanced societies power rests on gaining “the consent and the active participation of the great masses,” and that domination is sustained by “the intellectual and moral leadership” that turns the ruling class’s values into common sense. It is not coercion alone that sustains capitalism, but ideological consensus embedded in everyday institutions — family, education, media — that make the existing order appear normal and inevitable. Trump’s Board of Peace plays directly into this mode: styled as a peace-building institution, it gains legitimacy through performance and symbolic endorsement by diverse member states, while the deeper structures of inequality and global power imbalance remain untouched.

Worse, the Board’s structure, with contributions determining permanence, mimics the logic of a marketplace for geopolitical influence. It turns peace into a commodity, something to be purchased rather than fought for through sustained collective action addressing the root causes of conflict. But this is exactly what today’s democracies are doing behind the scenes while preaching rules-based order on the stage. In Gramsci’s terms, this is transformismo — the absorption of dissent into frameworks that neutralize radical content and preserve the status quo under new branding.

If we are to extract a path out of this impasse, we must recognize that the current quagmire is more than political theatre or the result of a flawed leader. It arises from a deeper collapse of hegemonic frameworks that once allowed societies to function with coherence. The old liberal order, with its faith in institutions and incremental reform, has lost its capacity to command loyalty. The new order struggling to be born has not yet articulated a compelling vision that unifies disparate struggles — ecological, economic, racial, cultural — into a coherent project of emancipation rather than fragmentation.

To confront Trump’s phenomenon as a portal — as Žižek suggests, a threshold through which history may either proceed to annihilation or re-emerge in a radically different form — is to grasp Gramsci’s insistence that politics is a struggle for meaning and direction, not merely for offices or policies. A Gramscian approach would not waste energy on denunciation alone; it would engage in building counter-hegemony — alternative institutions, discourses, and practices that lay the groundwork for new popular consent. It would link ecological justice to economic democracy, it would affirm the agency of ordinary people rather than treating them as passive subjects, and it would reject the commodification of peace.

Gramsci’s maxim “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” captures this attitude precisely: clear-eyed recognition of how deep and persistent the crisis is, coupled with an unflinching commitment to action. In an age where AI and algorithmic governance threaten to redefine humanity’s relation to decision-making, where legitimacy is increasingly measured by currency flows rather than human welfare, Gramsci offers not a simple answer but a framework to understand why the old certainties have crumbled and how the new might still be forged through collective effort. The problem is not the lack of theory or insight; it is the absence of a political subject capable of turning analysis into a sustained force for transformation. Without a new form of organized will, the interregnum will continue, and the world will remain trapped between the decay of the old and the absence of the new.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa ✍️

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoHistory of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor