Features

Back home working in Sri Lanka with WHO, ILO, World Bank and ICES

(Excerpted from Memories that linger: My journey through the world of disability by Padmani Mendis)

Although I had carried out assignments for all the WHO Regional Offices except the European Office quite early on in my journey, I had not really had the opportunity to work with WHO Colombo. That is until the year 2012 when the World Report on Disability was published jointly by WHO and the World Bank, a very significant event for disabled people worldwide. The Regional Office in New Delhi, for reasons best known to them, had selected Sri Lanka as a regional focal point for an official launch of the publication.

Dr. Lanka Dissanayake was handling the subject of disability in WHO Colombo and helped coordinate the event. Responsibility was shared by the Ministries of Social Services and that of Health. It was obvious to anyone that on this occasion the former held the floor. Disability was theirs and theirs alone. So clear they made it, that the Minister of Health left it to his deputy to attend the event. His position, it seemed, had been insulted. Such was the hierarchy.

Dr. Tom Shakespeare, one of the key figures behind the prestigious World Report, came from the UK to represent WHO and the World Bank. The launch was quite an affair. As is usual with the Ministry an exhibition of products made by disabled people was organised as well as a concert by them. A committee of six members from both ministries was set up to oversee arrangements. Dr. Dissanayake brought me into the committee. My task was to accompany Tom Shakespeare on a programme of visits she arranged for him. But she brought me in really because beyond the launch, she had another activity in mind.

And this is how she got the activity going. She took the opportunity of the launch of the publication to suggest to the two ministries that they launch at the same time the preparation of a National Plan of Action for Disability. This was later called the NAPD. The two ministries had naught to do but work with each other. To see the activity through she gave me an official position as a Consultant to work with the two ministries.

With the relevant officials, we brought together disabled people and others with expertise in various areas in particular groups to prepare the eight sections of the plan. These were based on the National Policy on Disability, NPD. My task, as well as providing advice, was the preparation of the written edited document based on the drafts submitted by the groups.

Much was achieved this way until it was time for an open forum. This was held with the participation of over 200 people. I have not to this day seen that many disabled people participate together with others at such an event in Sri Lanka.

The process did not end there. We followed through using the email to circulate the draft document as widely as possible. Feedback obtained was fed in until the draft was as complete as it could be. I estimated quite roughly that well over 600 people had participated in the preparation of that document.

Approved by the two ministries, it was submitted to cabinet by the Minister of Social Welfare. The formal document in the three languages has on its cover both ministries as co-producers. And a decade after our National Policy on Disability had been approved, we now had in 2014 a National Plan for its implementation.

How I wish that I could say that these documents were put into effect by government. No, that was never formally done. But one can still have some sense of satisfaction that much of the statements in the National Policy and strategies in the National Action Plan have even to some small extent been disseminated within and have pervaded our society. This is to be credited to concerned individuals and organisations, including academia dedicated to improving the situation of our disabled people over these many years.

It may also be that it was a result of these efforts as well as others that a consciousness grew in our society about the situation of our disabled people. And consequently, a consciousness also of their rights. And of what appeared to be associating disability with rights in the increasing public discourse and national dialogue. But no, not yet a major concern within government.

Following these few small steps, many hoped finally that Sri Lanka had taken a leap in 2016. This was when our country finally ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities or CRPD, on February 8 of that year. Nope. No action to follow. False alarm again. Our government was likely responding to outside pressure that this had to be done. The enabling legislation for the CRPD is, just to remind you, still in the pipeline. The mechanism for its implementation has never been given a thought.

Nonetheless the two National Human Rights Action Plans (NHRAPs) that were made at around this time included disabled people as a subject area. I participated in the preparation of the NHRAP 2012 – 2016. It had been decided that disability was to be a cross-cutting issue in this plan and I was invited to serve on the relevant drafting committees.

By the time NHRAP 2017 – 2021 was being prepared, Sri Lanka had approved the CRPD so Disability had a whole section to itself. Here I was appointed to the drafting committee of the Disability section. Both remained as documents prepared using expensive paper with a glossy cover.

The whole fiasco led one to believe the NHRAPs were made only to impress the international community. Or to respond to their vociferous requests for Sri Lanka to fulfil our international commitments.

Journeying with the International Labour Organisation, Colombo

Journeying with the ILO in Colombo took me into a completely new ethos. Work, employment and the right to an income that was not connected with Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR). The right to work is the area in which perhaps the rights of disabled adults are most violated. Just as for children the greatest violation would undoubtedly be the right to education.

The most interesting of the tasks I did for ILO was in the Factory Improvement Programme implemented by the EFC or Employers Federation of Ceylon. It was therefore called the ILO – EFC Factory Improvement Programme.

This was an ILO regional programme aimed at improving the overall efficiency levels and competitiveness of selected factories. Including disabled people in these factories was part of the programme. A manual for training factory managers to fulfil programme aims was being developed by ILO.

My task was to field test the module in the manual which dealt with the inclusion of disabled people. I was first required to visit 10 factories in the western province selected for the field test and motivate employers to include disabled people in their workplace. Most were garment industries, while a few were related to the tea trade. It was a first experience for me going inside these factories and meeting staff. The factories were exceptionally well maintained as were their gardens, usually landscaped. All very pleasant.

I was most surprised by this finding. That is, nine of the 10 factories already had disabled employees. Speaking with them, I found that these employees were quite content with their situation. The managers, it appeared needed no motivating from me. This finding did not quite match the situation we found on the ground. The National Census of 2012 indicated that unemployment among disabled people was over 70%. Field workers believe it is even higher.

Beyond this was another welcome finding. While I was on the floor of a certain garment factory with the factory manager, the bell rang announcing the tea break. All the workers on the floor left as if in a hurry to make the most of the free time they were given. Except for one young man who waited to look around him; he went up to a colleague’s machine, did something with it and then left.

The manager explained to me what it was about. The young man, let’s call him Nanda, looked around him to see if all was in order. He found that a colleague had failed to switch his machine off, and this is what Nanda did before leaving the floor. The manager went on to tell me that Nanda had, the previous year, been recognised as the “Best Employee”. Nanda was deaf. He communicated with his colleagues using gestures and signs they made up. His impairment was no barrier at this workplace.

At yet another factory, the manager was proud to show me around so I could see how he had integrated in his factory more than a dozen disabled employees. He went on to say to me “If you bring me 20 disabled people tomorrow, I will give them all work.” And who talks of the low productivity levels of these our people?

The World Bank

Two of the more interesting tasks I did for The World Bank I would like to share with you. They were quite different from each other. The first took me in 2009 to many parts of my country again talking with many people from many different walks of life and a variety of institutions. This learning and experience went into a comprehensive report I gave to The World Bank calling it “Disability in Sri Lanka”.

The first appointment I carried out for this task was with the Director-General of Labour. Before I entered the beautiful new building housing the Ministry and Department of Labour, I had a toss, fell flat on my face and injured my foot. It was awfully painful and I could see my foot swelling up immediately. Appointments with these people were hard to get so I went ahead with it. It was later when I got to a hospital that I found out I had a fracture. My foot was put in a plaster cast. It could not take any weight for six weeks.

And so I started using a wheelchair. And this I used until I had completed the task travelling to all parts of the island for my work. Accessible hotels were very hard to find. Many buildings and offices were inaccessible. But people were kind. Even top Government officials came down to earth to meet me, some down from their Ivory Towers.

For the second task of preparing a document, I worked with the Ministry of Health, disabled people and a few others. This was approved and published by the ministry as their rehabilitation policy in 2014 and called “National Guidelines for Rehabilitation Services in Sri Lanka”. The process of preparing it involving discussions with a wide range of health personnel seemed to make them conscious to some degree of the needs of disabled people.

ICES and the Disability Policy Brief

The last formal work I carried out on my journey was with the International Centre for Ethnic Studies, ICES. The ICES was popular in our world because of the interest it showed in disability. Dr. Mario Gomes, the Executive Director, could very easily be approached by both disabled people and by us disability workers for particular support that we needed. So over the years, many meetings and workshops were sponsored and some research conducted related to disability.

Disability by this time had moved out of the public discourse. Action on it seemed to be low-key. Binendri Perera, an attorney attached to the University of Colombo and I discussed with Dr. Gomes the possibility of preparing for publication a brief document that may help to change this situation. The outcome of this is the ICES publication “Disability Policy Brief for Law Makers, Administrators and Other Decision Makers” in all three languages.

What Binendri and I did was synthesise in the document in point form the National Policy and National Action Plan both of which had Cabinet approval and the UN Convention on Disability which Sri Lanka had ratified.

To do this we analysed each recommendation and put them into one chart so that they could be related to each other and compared. This we trusted would lead to a comprehensive approach to implementation. We believed this simple format would encourage users to understand their respective roles in the overall process and take whatever action they could. ICES made sure it was distributed to reach all districts in Sri Lanka and divisions within many of those districts. One last attempt to move closer to a better life for our disabled people.

End of travel, but not of The Journey

I started my Journey in the World of Disability here at home in my Sri Lanka. I have shared with you the first small step of my journey that I took while yet at school with my decision to be a physiotherapist. And with that first step, the next to proceed to the UK to be an Orthopaedic Nurse as a means of studying to be a Physiotherapist.

It was right at the start of the five years and more of learning this process took that I made my contacts with disabled people of all ages. First as their nurse, to many their friend and confidante. Space permits me to share with you my experiences with only a few individuals of the many thousands that impacted my life as it was to unfold.

The first was but a small step, but one that led to all the steps I have taken since, taken during the next 65 years of my life to the age of 83 where I am now, back home where I started. Sharing my memories with you.

During the 64 years that I journeyed, unending opportunities made for me a journey that criss-crossed continents. When asked about it I have said that “I travel horizontally”. Because whilst I was in South America and the Caribbean during the early years, the rest of my journey I have spent in Asia, Africa and much of it in between, in the Middle-East. To me that is more important than the journeys I made North-South, although to participate in the many conferences, meetings and workshops in the industrialised north was also rewarding, as much as it was in the countries of the global south. And, of course, to share my learning through the innumerable teaching opportunities in many of the same countries.

Since about six years or so ago, physical impairment and difficulties have ended travel for me. But my journey is not ended. This continues in the Realm of Disability to this day. Modern communication technology makes it possible to meet North to South and East to West. Skype and Zoom and the good old telephone itself are a boon. My same dining table still serves as a conference table when I sit with the many visitors who come to talk with me about the situation of disabled people in Sri Lanka and elsewhere, past and present.

To share with you how my journey continues as of now here at home are just two examples. Last week I was interviewed by a Master’s student named Nathaniel from Columbia University in New York. About certain aspects of disability in Sri Lanka. But our discussion and my sharing also brought into it an international perspective. He was involved in a multi-country research study related to inclusive adolescent health care, the Report of which will be presented to a UN agency.

The second, a few months ago I was interviewed by Taryn from Mc Gill University in Montreal, Canada, also on zoom. She was carrying out a study related to women activists in Sri Lanka. I told her I did not consider myself to be an activist. But her definition being what it was she could not accept my reasons for that, and we had a really interesting discussion. Which came to be focused on my global journey in disability as it impacted my work in Sri Lanka.

And with that, it is time now to move on. To move on and reflect on my life as I lived it and on these the memories I shared with you.

Features

The middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

The problem isn’t our intentions, it’s our approach. We treat financial management as a personality flaw that needs fixing, rather than a skill that needs the right strategy. This year let’s try something different. Let’s put actual behavioural science behind how we handle our rupees.

Based on the article ‘Seven proven, realistic ways to improve your finances in 2026’ published on 1news.co.nz, I aim to adapt these recommended financial strategies to the Sri Lankan context.” Here are seven money habits that work because they’re grounded in how humans actually behave, not how we wish we would.

While these strategies offer useful direction for strengthening personal financial management, it is important to acknowledge that they may not be suitable for everyone. Many households face severe financial pressure and cannot realistically follow traditional income allocation frameworks, such as the well-known but outdated Singalovada Sutta guidelines, when even meeting daily food expenses has become a struggle. For individuals and families who are burdened by escalating costs of essentials, including electricity, water, mobile connectivity, transport, and other non-negotiable commitments, strict adherence to prescriptive models is neither practical nor fair to expect. Therefore, readers should remain mindful of their own financial realities and adapt these strategies in ways that align with their income levels, essential obligations, and broader personal circumstances.

1. Your Money Problems Aren’t Moral Failures, They’re Data Points

When every rupee misspent becomes evidence of personal failure, we stop looking for solutions. Shame is a terrible problem-solver. It makes us hide from our bank statements, avoid difficult conversations, and repeat the same mistakes because we’re too embarrassed to examine them.

Instead, try replacing judgment with curiosity. Transform “I’m terrible with money” into “That’s interesting, why did I make that choice?” Suddenly, mistakes become information rather than indictments. You might notice you overspend at Odel or high-end restaurant when stressed about work. Or that you commit to expensive plans when feeling socially pressured. Perhaps your online shopping peaks during power cuts when you’re bored and frustrated.

2. Forget the Year-Long Marathon, Focus on 90-Day Sprints

A Sri Lankan year is densely packed with financial obligations: Sinhala/Tamil Avurudu, Christmas, Vesak, and Poson celebrations; recurring school fees; seasonal festival shopping; wedding and almsgiving periods; yearend festivities; and an evergrowing list of marketing-driven occasions such as Valentine’s Day, Father’s Day, Mother’s Day, and many others. Each of these events carries its own financial weight, often placing additional pressure on already-stretched household budgets.

Research consistently shows that shorter time frames work better. Ninety days is long enough to create a meaningful change, but short enough to maintain focus and momentum. So instead of one overwhelming annual goal, give yourself four quarterly upgrades.

In the first quarter, the focus may be on organising your contributions toward key duties and responsibilities, while also ensuring that you are maximising the available benefits for your designated beneficiaries. Quarter two could be about building a small emergency fund, even Rs. 10,000 provides breathing room. Quarter three might involve auditing your bills and subscriptions to eliminate unnecessary expenses. Quarter four could be when you finally start that investment you’ve been postponing. You don’t need superhuman discipline or complicated spreadsheets, just focused attention, one quarter at a time.

3. Make One Decision That Eliminates Weekly Worry

The best money decisions are the ones you make once but benefit from repeatedly. These are decisions that permanently reduce what behavioural economists call “decision fatigue”, the mental exhaustion that comes from constantly managing money in your head. What’s one choice you could make today that would remove a recurring financial worry?

It might be setting up an automatic standing order to transfer Rs. 10,000 to savings the day your salary arrives, before you can spend it. Maybe it’s consolidating your scattered savings accounts into one that actually pays decent return.

These aren’t dramatic moves that require personality transplants. They’re structural decisions that work with your human tendency toward inertia rather than against it. Most banks now offer seamless digital automation. You can set it up once and benefit from that decision every single month without additional effort or willpower. You make the decision once. You benefit all year. That’s leveraging your energy intelligently.

4. Stop Spending on Who You Think You Should Be

Sri Lankan society comes with heavy expectations. The car you drive, the school your children attend, the hotels you patronise, the brands you wear, all communicate your worth, or so we’re told. Much of our spending isn’t about actual enjoyment. It’s about meeting unspoken expectations, keeping up appearances, or aspiring to a version of us that doesn’t actually exist.

We buy expensive saris we’ll wear once because everyone does. We maintain memberships to clubs we rarely visit because it looks good. We say yes to weekend plans at overpriced restaurants because declining feels like admitting we can’t afford it. We upgrade phones not because ours stopped working, but because others have.

Before your next purchase, ask yourself: do I actually want this, or do I want to want it? If it’s the second one, walk away. You won’t miss it. This isn’t about deprivation, it’s about precision. When you stop spending to perform and start spending to support the life you genuinely enjoy, money pressure eases dramatically. Your resources align with your actual values rather than imagined expectations.

Maybe you don’t care about fancy restaurants, but you love long drives along the southern coast. Maybe branded clothing leaves you cold, but you’d spend any amount on art supplies or books. That’s fine. Spend accordingly.

5. Break One Habit, See If You Actually Miss It

We’re creatures of routine, which serves us well until those routines outlive their usefulness. Sometimes we spend money on habits that started for good reasons but no longer serve us. Alpechchathava, in Buddha’s teaching, means living contentedly with few desires. It guides a person to manage money wisely by avoiding excess spending, unnecessary debt, and craving, and by focusing on essential needs and wholesome priorities. In this way, wealth supports mental cultivation, generosity, and spiritual progress.

The daily kottu roti that once felt like a convenient solution after working late may now have turned into an unnecessary routine. Similarly, frequent P&S or Caravan snack runs, and the habit of picking up sugary treats like cakes and sweets, are not only costly but also wellknown to be unhealthy, as nutritionists consistently point out. Beyond food, other expenses such as magazine subscriptions, the monthly coffee meetup, or weekend mall browsing often continue on autopilot without us realising how much they add up. These seemingly small, habitual expenses can quietly drain your budget while offering very little longterm value.

Try this experiment: keep a money diary for one week. Note every expense, no matter how small. Then identify one regular spend and eliminate it for the following week. If you don’t miss it? Excellent, keep it gone. If you genuinely miss it? Add it back without guilt. This isn’t about permanent sacrifice.

It’s about snapping yourself out of autopilot and checking whether your spending still reflects your current reality, priorities and purchasing power. You might discover you’re spending Rs. 15,000 monthly on things you barely notice.

6. Create Your Crisis Playbook on a Good Day

Many financial disasters don’t happen because we’re careless, they happen because we’re panicked. When crisis strikes, job loss, medical emergency, unexpected business downturn, fear hijacks our decision-making. Our rational brain exists while panic makes expensive choices: high-interest personal loans, selling investments at losses, making commitments we can’t sustain.

The solution? Make your crisis plan before the crisis arrives. On a calm day, sit down and document: If I lost my income tomorrow, what would I do first? Which expenses are truly essential? What’s the absolute minimum I need to function? Who could I call for advice? Which savings are untouchable, which could be accessed if necessary? What government support or loan restructuring options exist (Not in Sri Lanka)? This is a sort of preparation for sudden shocks.

7. Question the Money Stories You Inherited

Sometimes our biggest financial obstacles aren’t failed attempts, they’re the attempts we never make because we’ve internalised limiting stories. “Our family was never good with money.” “Investing is for rich people.” “I’m just not the type who earns more.” “Women don’t understand finance.” These narratives, absorbed from family, culture, or past experiences, become invisible fences.

Question them. Where did this belief originate? Is it actually true, or is it a story you’ve been telling yourself for so long, it feels like fact? What would happen if you tested it? Often, these stories protect us from the discomfort of trying and potentially failing. But they also protect us from the possibility of succeeding. And that’s a far costlier protection than most of us realise.

The Bottom Line

Improving your finances in 2026 doesn’t require becoming a different person. It requires understanding the person you already are, your patterns, triggers, and tendencies, and working with them rather than against them.

These aren’t magic solutions. They’re evidence-based approaches that acknowledge a simple truth: you’re not broken, and your money management doesn’t need fixing through willpower alone. It needs better systems, clearer thinking, and a lot less shame.

Features

Public scepticism regarding paediatric preventive interventions

A significant portion of the history of paediatrics is a triumph of prevention. From the simple act of washing hands to the miracle of vaccines, preventive strategies have been the unsung heroes, drastically lowering child mortality rates and setting the stage for healthier, longer lives across the globe. Simple measures like promoting personal hygiene, ensuring the proper use of toilets, and providing Vitamin K immediately after birth to prevent dangerous bleeding, have profound impacts. Advanced interventions like inhalers for asthma, robust trauma care systems, and even cutting-edge genetic manipulations are testament to the relentless and wonderful progress of paediatric science.

A shining beacon that has signified increased survival and marked reductions in mortality across the board in all paediatric age groups has been the development of various preventive strategies in the science of children’s health, from newborns to adolescents. The institution of such proven measures across the globe, has resulted in gains that are almost too good to be true. From a Sri Lankan perspective, these measures have contributed towards the unbelievable reduction of the under-5-year mortality rate from over 100 per 1000 live births in the 1960s to the seminal single-digit figure of 07 per 1000 live births in the 2020s.

Yet for all this, despite the overwhelming evidence of success, a most worrying trend is emerging. That is public scepticism and pessimism regarding these vital interventions. This doubt is not a benign phenomenon; it poses a real danger to the health of our children. At the heart of this challenge lies the potent, often insidious, spread of misinformation and disinformation.

The success of any preventive health strategy in paediatrics rests not just on its scientific efficacy, but on parental cooperation and commitment. When parents hesitate or refuse to follow recommended guidelines, the shield of prevention is compromised. Today, the most potent threat to this partnership is the flood of false information.

Misinformation is false information spread unintentionally. A well-meaning friend sharing a rumour about a vaccine side-effect they heard online is spreading misinformation.

Disinformation is false information deliberately created and disseminated to cause harm or sow doubt. This often comes from organised groups or individuals with vested interests; sometimes financial, sometimes ideological, who seek to undermine public trust in medical institutions and scientific consensus.

The digital age, particularly social media, has become the prime breeding ground for these falsehoods. Complex scientific data is reduced to emotionally charged, simplistic, and often sensationalist soundbites that travel faster and farther than the truth.

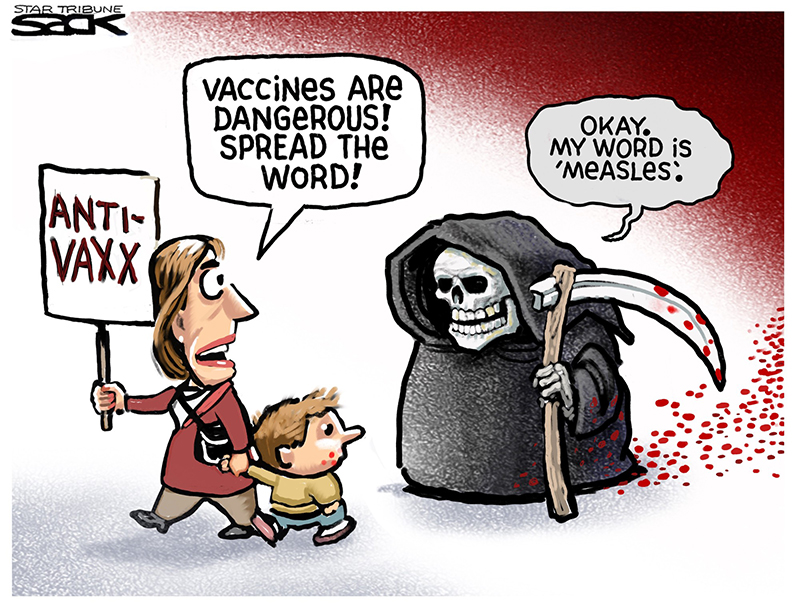

The most visible battleground is childhood vaccination. Decades of robust, high-quality research have confirmed vaccines as one of the most cost-effective and successful public health interventions ever conceived. Global vaccination efforts have saved an estimated 150 million lives in the past 50 years, eradicating or drastically controlling diseases like polio, measles, diphtheria, and tetanus.

However, a single, long-retracted, and scientifically debunked paper claiming a link between the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism continues to be weaponised by disinformation campaigns. This persistent myth, despite being soundly disproven, taps into deep-seated fears about children’s development. Other common vaccine myths target ingredients such as trace amounts of aluminium or mercury, which are harmless in the quantities used and often less than what is naturally found in food or the idea that “natural immunity” from infection is superior, totally ignoring the fact that natural infection carries the devastating risk of severe complications, long-term disability, and even death. The tangible consequence of this doubt is the dropping of childhood vaccination rates in various communities, leading to the wholly unnecessary re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

Scepticism is not limited to vaccines. It can touch any area of paediatric preventive care where an intervention might seem unnecessary, invasive, or have perceived risks. Routine screenings for speech disorders, motor skills, or mental health issues can sometimes be perceived as medicalising normal childhood variations or putting a “label” on a child. Parents may resist or delay screening, missing the critical window for early intervention of proven measures that are likely to help. Advice on managing childhood obesity, reducing screen time, or adopting a balanced diet can be viewed by some parents as intrusive or judgmental, leading to poor adherence to essential health-promoting behaviours.

The regular use of inhalers for asthma or other chronic conditions might be looked down upon due to the fear of “dependency”, “addiction”, or long-term side effects, despite medical consensus that these preventive measures keep conditions controlled and prevent life-threatening exacerbations.

The common thread is a lack of understanding of the risk-benefit ratio. Parents, bombarded by fear-mongering narratives, often overestimate the rare, mild risks of an intervention while catastrophically underestimating the severe and permanent risks of the disease or condition itself.

The power of paediatric preventive medicine is not in a single shot or pill, but in the consistent, committed partnership between healthcare providers and parents. Paediatric science, driven by rigorous evidence-based medicine, do continue to refine guidelines, conduct transparent research, and communicate its findings clearly. When guidelines are confusing or lack robust evidence, it naturally creates openings for doubt. The scientific community’s commitment to continuous quality improvement and accessibility is paramount.

Ultimately, the success of prevention rests with the parents. Parenting, as a vital form of preventive care, includes all activities that raise happy, healthy, and capable children. The simple, non-medical steps mentioned in the introduction, proper handwashing, good sanitation, and encouraging exercise, are all forms of parental preventive intervention.

For more complex interventions, parental commitment requires several actions. They need to seek and trust the guidance provided by qualified healthcare professionals over anonymous, unsubstantiated online claims. They need to engage in an open dialogue by asking relevant questions and expressing concerns to doctors in an open, non-confrontational manner. A good healthcare provider will use this as an opportunity to educate and build trust, and not a portal to simply dismiss concerns. Then, of course, there is the spectre of adherence to various protocols and actions by the parents. These include consistently following recommended schedules, whether for well-child checkups, vaccinations, or daily medication protocols.

Addressing public scepticism requires a multi-pronged, collaborative strategy. It is not just about correcting false facts (debunking), but about building resilience against future falsehoods (prebunking). The single most influential voice in a parent’s decision-making process is their paediatrician or primary care provider. Clinicians must move beyond simply reciting facts. They need to use empathetic communication techniques, like Motivational Interviewing (MI), which focuses on active listening, validating parental concerns, and then collaboratively guiding them toward evidence-based decisions. For example, responding with, “I hear you’re worried about the side-effects you read about. Can I share what we know from decades of safety monitoring?” Being open about common, minor side effects such as a short-lasting fever after a vaccine pre-empts the shock and distrust that occurs when an expected, yet unmentioned, reaction happens.

Public health campaigns must go on the offensive, not just a defensive fact-checking spree. Teaching the general public how disinformation works, the use of “fake experts”, selective cherry-picked data, and conspiracy theories all add up to a most powerful form of inoculation (prebunking) against future exposure. Health institutions must simplify their communications and make verified, high-quality information easily accessible on platforms where parents are already looking.

Parents often trust their peers as much as their doctors. Engaging local community leaders, faith leaders, and even trusted social media influencers to share accurate, positive messages about paediatric health can shift the public narrative at a grassroots level. While protecting privacy, sharing aggregate data and stories about the dramatic decline in childhood diseases thanks to prevention can re-emphasise the collective good.

The battle against child mortality and morbidity has been one of the great human achievements, a testament to scientific ingenuity and collective effort. Today, the greatest threat to maintaining these gains is not a new virus, but a breakdown of trust fuelled by unchecked falsehoods.

Paediatric preventive interventions, from a cake of soap and a proper toilet to the most sophisticated genetic therapies, are the foundation of a healthy future for every child. To secure this future, the scientific community must remain transparent, the healthcare system must lead with empathy, and the public must commit to informed, critical thinking. By rejecting the noise of disinformation and embracing the clear, evidence-based consensus of science, we can ensure that every child continues to benefit from the life-saving progress that defines modern paediatrics. The well-being of the next generation demands nothing less than this renewed commitment.

Little children are not in a position to make abiding decisions regarding their health, especially regarding preventive strategies in health. It is ultimately the crucial decisions made by responsible parents regarding the health of their children that really matter. As doctors, our commitment is never to leave any child behind.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera ✍️

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

Attacks on PM vulgar, misogynistic; education reforms welcome

We express our profound concern and deep outrage at the vulgar, misogynistic, and defamatory attacks being directed at the Prime Minister and Minister of Education, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya.

Dr. Harini Amarasuriya is not merely a political leader; she is a scholar, public intellectual, and lifelong advocate of social justice, equality, and education. Attempts to discredit her through personal abuse rather than reasoned policy debate are not only an insult to her, but an assault on democratic values, women’s leadership, and intellectual integrity in public life.

Such attacks are unjust and unethical, and they corrode democratic discourse. We are deeply disappointed that certain political actors and their supporters continue to rely on misinformation, prejudice, and emotional manipulation, instead of engaging in rational, evidence-based, and constructive debate.

Sri Lanka has already paid a heavy price for decades of politics rooted in fear, communal division, and sentiment-driven populism. The country’s economic collapse and social breakdown are the direct consequences of these failed approaches. The people decisively rejected this style of politics through the Aragalaya, signaling a clear demand for change. Sri Lanka now stands at a historic turning point. After decades of corruption, ethnic manipulation, and policy paralysis, the people have given a clear mandate for systemic reform.

At this critical moment, Sri Lanka urgently needs structural reforms, particularly in education, which is the foundation of long-term national development, social mobility, and global competitiveness. Yet we observe that the very forces responsible for the country’s decline are once again attempting to block or derail reforms by exploiting religious, cultural, and emotional narratives.

We strongly affirm that no nation can be rebuilt through hatred, fear, or division. Education reform is not a political threat; it is a national necessity. Efforts to undermine reform through personal attacks and manufactured controversies serve only those who seek to return to power by keeping the country weak, divided, and intellectually impoverished.

Those who now attack Dr. Harini Amarasuriya are not defending culture or morality. They are defending privilege and political survival. Having failed the country for over seventy-five years through communalism, patronage, and anti-intellectualism, they now fear that an educated, critical, and empowered generation will render their outdated politics irrelevant.

This is why they target:

=a woman,

=an academic,

=and a reformer.

We therefore state clearly that we:

1. Condemn all forms of character assassination, gender-based attacks, and hate propaganda against the Prime Minister and Minister of Education.

2. Affirm our full support for Dr. Harini Amarasuriya’s leadership in advancing Sri Lanka’s education reforms.

3. Urge the government to proceed firmly and without retreat in implementing the proposed education reforms, in line with national policy and the public mandate.

4. Call upon academics, professionals, teachers, parents, and citizens to stand together against reactionary forces that seek to sabotage reform through fear mongering and disinformation.

A country cannot be rebuilt by those who destroyed it. A future cannot be created by those who fear education reforms.

Sri Lanka’s future must not be sacrificed for the ambitions of a few.Sri Lanka must move forward — with knowledge, dignity, and courage.

Signatories:

1. Markandu Thiruvathavooran, Attorney at law

2. S. Arivalzahan, University of Jaffna

3. Dr S.Ramesh, University of Jaffna

4. Dr. Mariadas Alfred, Former Dean, University of Peradeniya

5. Prof B.Nimalathasan, Senior Professor, University of Jaffna

6. S. Srivakeesan, Station Master, SriLankan Railways

7. A. T. Aravinthan, Branch Manager, Commercial Bank

8. Dr. S. Niththiyaruban, Paediatrician, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

9. Dr. S. Selvaganesh, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

10. Dr. S. Mathievaanan, Consultant Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

11. Prof. P. Iyngaran, University of Jaffna

12. Eng. M. Sooriasegaram, President, Education Development Consortium

13. Dr. S. Raviraj, Senior Consultant Surgeon, Former Dean, Faculty of Medicine, University, Jaffna.

14. Mr. Saminadan Wimal, University of Jaffna

15. Dr. A. Antonyrajan, University of Jaffna

16. P. Regno, Attorney at Law

17. Prof. J. Prince Jeyadevan, University of Jaffna

18. Prof. S. Muhunthan, University of Jaffna

19. Prof. R. Kapilan, University of Jaffna

20. Dr. S. Jeevasuthan, University of Jaffna

21. J.S. Thevaruban, University of Jaffna

22. S. Balaputhiran, University of Jaffna

23. Dr. N. Sivapalan, Retired Senior lecturer, University of Jaffna

24. I. P. Dhanushiyan, University of Jaffna

25. Dr. K. Thabotharan, University of Jaffna

26. Dr. Bahirathy J. Rasanen, University of Jaffna

27. Perinpanayagam Ronibus, Vice Secretary, Change Charitable Trust, Jaffna

28. Dr. S. Maheswaran, University of Peradeniya

29. Mr. S. Laleesan, Principal, Kopay Teachers’ College

30. Victor Antany, Teacher, Kilinochchi

31. K. Shanthakumar, Principal, Technical College, Vavuniya

32. S. Thirikaran, Principal, J/ Puttur Srisomaskanda College

33. Dr. T. Vannarajan, Advanced Technical Institute, Jaffna.

34. X. Don Bosco, Resource person, Piliyandala Educational Zone

35. K. Ravikumar, Regional Manager, Powerhands Pvt Ltd

36. Sathiyapriya Jeyaseelan, DO, Economist

37. A. Kalaichelvan, Chief Accountant, Animal Productive & Health

38. C. Vathanakumar, Retired Project Director

39. P. Kirupakaran, Department of Buildings (NP)

40. A. Antony Pilinton, David Peris Company, Jaffna

41. A. Muralietharan, Social Activist

42. Sinthuja Sritharan, Independent Researcher

43. T. Sritharan, Social Activist

44. Ms. Gnasakthi Sritharan, Social Activist

45. P. Thevatharsan, Management Service Officer

46. . S. Mohan, Social Activist

47. K. Jeyakumaran, Social Activist

48. Dr. N. Nithianandan, Chairman, Ratnam Foundation

49. George Antony Cristy, Social Activist

50. S. Thangarasa, Social Activist

51. N. Bhavan, Retd. Deputy Principal, Mahajana College

52. P. Muthulingam, Executive Director, Institute of Social Development, Kandy

53. M.K. Sivarajah, Social Activist

54. Mr. V. Sivalingam, Human Rights Activist

55. S. Jeyaganeshan, Samuthi Development Officer

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective