Features

Royal-Thomian dance nearly cost me job of Secretary of Prohibition Commission

Excerpted from A Cabinet Secretaries Memoirs by BP Pieris

(Continued from last week)

In July, 1950, I was asked to be, in addition to my own duties, Secretary-General to the Standing Committee of the Commonwealth Consultative Committee, which went on till September. This was a follow up of the Colombo Plan. The Secretariat was housed in the Cabinet office and work went on each day till about midnight. The Police were on duty to prevent access by strangers, and they were kind enough to provide a van to take the members of my staff to their homes after the day’s work was over as no public transport was available at that time.

The Ceylon Delegation consisted of A. G. Ranasinha, K. Williams, R. Coomaraswamy and N. J. Jansz. All the other Commonwealth countries were represented and they worked out the details of implementing the Colombo Plan. It was at one of these meetings that two of the delegates nearly came to blows. An afternoon meeting had been adjourned at 5 p.m. to resume at 9 p.m. to enable delegates to attend a cocktail party.

On resumption, some of the delegates appeared not to be in a mood to carry on a “sober” and level-headed discussion. In vino, the most innocent observation can be misunderstood. And it was unfortunate that the exchange of words took place between the two senior delegates of two of the most senior Dominions of the Commonwealth. “What did you mean by that?” asked one delegate of the other. The other said “I have used plain English words and, if you don’t know the meaning, look up a dictionary.”

The first, grabbing the arms of his chair and going red in his already very tomato face, said “Will you repeat that?” and then the meeting heard the cool, calm voice of the Chairman, A. G. Ranasinha, saying “Gentlemen, we are all very tired. I am sleepy. Hadn’t we better adjourn now and meet tomorrow morning?” The next day, one of the other delegates asked me “Why do you Ceylonese chaps make, such good Chairmen?”

My next assignment, in 1951, was more important. It was as Secretary-General to the Consultative Committee on Economic Development in South and South-East Asia. Ranasinha was again unani-

mously elected Chairman and the following countries were represented: Australia 2, Burma 2, Cambodia 2, Canada 4, Ceylon 2, India 4, Indonesia 2, New Zealand 2, Pakistan 3, Philippines 2, Thailand 1, United Kingdom 6, United States of America 2, Vietnam 2, International Bank 1 and the Technical Bureau 1.

I was given two assistants, Mrs Imogen Kannangara and Miss Canakaratne, who knew shorthand, a daughter of Mr Justice Canakaratne. My assistants found great difficulty in taking down what the American delegate said because we were not used to the American way of speaking English. I therefore asked Miss Canakaratne to sit with her notebook immediately behind the American delegate’s chair and take down in shorthand all that he said. The other lady made a note in longhand and naturally there were discrepancies in the two versions which I, as Secretary-General, had to reconcile.

The proceedings were in English which language the Cambodian delegate did not understand. He spoke only French and refused to attend the meetings after the first as there was no French translator at the meeting. I wonder what would have happened if the Ceylonese delegate had insisted on addressing the meeting in our official language.

A number of proposals for a continuing organization was placed before the meeting, but it was considered premature to determine precise arrangements until the size and scope of the external finance available to the countries were better known. The meeting agreed that the representatives of the various countries should meet by mutual consent, at least once a year, and that a small secretariat should be established.

The President of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, by letter, informed the meeting that the Bank welcomed the opportunity to cooperate with the Governments in the preparation of their development programmes and in financing as large a part of those programmes as each country’s creditworthiness would allow. All the richer countries were willing to help. I reproduce an extract of a speech made in the Canadian Parliament by Mr Lester Pearson:

“We must also do what we can to improve the economic conditions and human welfare in Free Asia. We must try to work with, rather than against, the forces struggling for a better life in that part of the world. Such cooperation may in the long run become as important for the defence of freedom – and therefore for the defence of Canada – as sending and army to Europe, in the present immediate emergency.

“Many members in the House will have read the Colombo Plan for cooperative economic development in South-East Asia. This imaginative and, I think, well-founded report, which was published last November, as a result of the work of the Commonwealth Consultative Committee, points the way to the kind of effective assistance which we in the West can offer to the free peoples of Asia. They stand in very great need of capital for economic development and of technical assistance.

“For Canada to supply either the capital or the technical assistance in any substantive volume would mean considerable sacrifice, now that the demands of our defence programme are imposing new strains on our economy. On the other hand, I personally have been struck by the modesty and good sense which such countries as India and Pakistan have shown in drawing up plans for their own development for the next six years.

“The countries of South and South-East Asia which have drawn up programmes for inclusion in the report with populations involved including nearly one quarter of the population of the world state that they require, over the six year period, external finance to the amount of three billion dollars, the greater part of which will be supplied by the release of sterling balances in London.

“I believe that a Canadian contribution to these programmes, even if it has to be smaller than we might be able to make if we were not bearing other and heavy burdens, would have a great effect, not only in doing something to improve the standard of living in that part of the world, but also in convincing the people there of our sympathy and our interest. It is for these reasons, Mr Speaker, that the Government has decided to seek the approval of the House for an appropriate Canadian contribution to the Colombo Plan.”

The Conference ended, after the customary farewell speeches, with a cocktail party at the Chairman’s house.

I was next appointed as Secretary to the Prohibition Commission. It happened at one of Sir John’s Cabinet meetings. I, as Secretary, sat on the right of the Prime Minister, and next to me was the Home Minister, A. Ratnayake, who was in charge of Excise. Without presenting a Cabinet Paper, the Minister asked orally that a commission be appointed to inquire into the question of Prohibition and Gambling, including Racing.

The Prime Minister, addressing Ratnayake, and patting me on the back, said “Yes, Ratty, I’ll give you the most efficient secretary you can have”. Ratnayake, who was taken completely by surprise when a matter of such importance was decided so quickly, inquired – who the secretary was to be, and, Sir John, again patting my back said “Our friend here, man”. Ratnayake protested and said that as Excise was his subject, he surely should be allowed to select the secretary.

It was obvious that he had something to say against me, and one Minister suggested that I should leave the room for a moment. When I was recalled a few minutes later, the Prime Minister said “Well, Peiris, you are the Secretary. Carry on and do a good job.”

I was curious to find out what Ratnayake had against me, but I did not like to ask any of the Ministers. When the meeting was over and I had got back to my room, my telephone rang. Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan, Minister of Housing, who retired from the public service as Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs, and whom I knew very well, was at the other end of the line.

He said “Now, Percy, that you are the Prohibition Secretary, remember not to dance in public on Royal-Thomian nights.” I was amazed. I asked him whether t that was all that Ratnayake had to say against me, and he said “Yes”.

Which leads me to the story of my dance. My only child, a daughter who passed her Senior School Certificate Examination at the age of 15 decided to follow a course in agriculture and animal husbandry at the Girls’ Farm School at Kundasale. When the vacation was due, she asked me whether she might invite about six other girls home for the holidays and I readily agreed.

The girls were trained and used to a fairly rough life; – they could cook, run a house, sleep on mats on the floor, and were not likely to cause us any inconvenience. They came. In the evenings, I used to sit at the piano and play for them while they did a sowing and reaping dance. I watched them carefully for some days, got the e hang of the dance, and used to practice the steps and the body movements in the privacy of the bathroom.

Soon I was confident that I could perform the dance in public and bought a set of foot-bells. A niece of mine gave me a full length green skirt and a black blouse into which I used to stuff about a dozen handkerchiefs at the appropriate places.

On the night preceding the opening day of the Royal-Thomian match, there has always been a stag party in the College grounds, attended by about 600 old boys. That year, there was a large bar which was well patronized. There was no hired orchestra. Music was supplied by the old boys in turn. One would sit at the piano, another would take up a fiddle, a third a saxophone and someone else would sit at the drums.

The drink had to be carefully looked after because, if it was left unattended for a moment, it was pinched. On the night in question, I wanted to go with my skirt, blouse and handkerchiefs, but my daughter advised against it as the skirt needed a lot of fixing with safety pins and there would be no one to fix it for me. I therefore carried the foot-bells in my pocket.

Suddenly I heard what I call “my piece” being played. I threw my shoes, tied the bells, mounted the platform, and danced. It was appreciated by all. There were eight ministers, including Ratnayake, in the hall waiting for dinner. After my dance, I walked up to their table with my drink in my hand to show them that it was not an excess of alcohol that made me perform. The Minister of Justice, Wikramanayake said “B. P., I am going to move in the next Cabinet that your salary be enhanced in view of your added qualifications.” Minister of Lands Bulankulama. Dissawe said that he did not know that I had such a supple body. That was the spirit in which my act was taken, and it nearly cost me my Prohibition Secretaryship.

One of the first things the Prohibition Commissioners did was to address the Governor-General requesting that the remuneration payable to them should be regarded as a nontaxable allowance for meeting out of pocket expenses. I advised against the move because it gave the impression that the Commissioners were more concerned about the safeguarding of their financial interests than sitting down to the task which had been entrusted to them.

The question was one which they should have raised before they accepted their appointments. In the second place, if the request had been granted, it would have necessitated an amendment of the Income Tax Ordinance, and the same concession would have had to be extended to other Commissions then sitting, and which would be appointed in the future.

The principle that payment to members of Commissions should be regarded as remuneration and therefore taxable had been accepted for several years. I had to point all these matters out when the Governor-General referred the Commissioners’ letter to the Cabinet for advice: the advice was that the request should not be granted.

As I was also, at this time, the Secretary to the Cabinet, the Commissions found it difficult to fix the days for its sittings. Cabinet meetings are summoned at short notice. The Commission’s sittings had to be fixed well in advance because witnesses giving evidence had to be notified in time. If both meetings fell on the same day, the Commission would have been without a Secretary, as I would have had to attend the Cabinet. The Commission, therefore, asked for a full-time Secretary to attend to their work.

Sir John did not agree to this; he wanted me to continue as Secretary, and gave them a full-time Assistant, Shantikumar Tampoe Phillips, a young Civil Servant and an English Honours man. Between the two of us, we wrote a ‘suitable’ report, I writing the legal chapters and he the rest, which amounted to about three-quarters of the whole. I am not too shy to say that it is a well-written report but the credit and praise for it must go to Phillips.

We examined the history of nearly every country in which total or partial prohibition had been tried: the United States of America, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, even Russia under the Czarist regime, and an Islamic country like Turkey. Everywhere, it had been a sorry record of failure. The story of prohibition in India is known to all. With this world picture before us, the Commission came to the conclusion that prohibition could not be successfully enforced in Ceylon.

Features

2025 Budget: Challenges, hopes and concerns

Sri Lanka’s recent government budget has sparked both hope and concern. While some see it as a positive step toward improving the country’s economy, others worry about whether the government’s proposals can be successfully implemented. This analysis explores the budget’s approach and what it could mean for the country’s financial future.

Sri Lanka’s recent government budget has sparked both hope and concern. While some see it as a positive step toward improving the country’s economy, others worry about whether the government’s proposals can be successfully implemented. This analysis explores the budget’s approach and what it could mean for the country’s financial future.

Credit Rating Improvement and What It Means

Fitch Ratings recently upgraded Sri Lanka’s credit rating, moving it from a risky “Restricted Default” (RD) to a “CCC+” rating. This shows that the country’s financial situation is improving, though it still faces a high risk of default. The government aims to increase its revenue, especially through trade taxes and income tax, but experts warn that the success of these plans is uncertain, particularly when it comes to lifting restrictions on imports.

Economic Democracy and Market Regulation

The government claims that this budget is based on the idea of “economic democracy,” aiming to balance market forces with government control. While it promises fairer distribution of wealth, critics argue that it still relies on market-driven policies that may not bring the desired changes. The budget seems to follow similar strategies to past administrations, despite the government’s claim of pursuing a new direction.

The current government, led by a Marxist-influenced party, has shifted its approach by aligning with global economic institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This represents a departure from its previous, more radical stance. The government’s vision focuses on rural development, support for small businesses, and an export-driven economy, continuing strategies from previous administrations rather than implementing drastic changes.

Stability and Continuity in Policy

One of the more positive aspects of the budget is its consistency with the fiscal policies of the past government. Sri Lanka’s economy has suffered from sudden policy changes in the past, often triggered by political transitions. By maintaining a steady course, the current government seeks to ensure stability in the recovery process, despite criticisms from political opponents.

Sri Lanka continues to face significant financial challenges, including a large budget deficit. The government’s spending in 2025 is expected to exceed its revenue by about LKR 2.2 trillion, leading to a deficit of around 6.7% of GDP. To cover this gap, the government plans to borrow both locally and internationally. However, debt repayment remains a major concern, with billions needed to settle existing obligations.

Tax Revenue and Public Spending Issues

Sri Lanka’s tax collection remains critically low, which worsens the country’s financial troubles. Tax evasion, exemptions, and inefficient administration make it hard to collect sufficient revenue. The government has raised VAT to 18% to boost income, but this could increase inflation, further harming families’ ability to afford basic goods. Additionally, corruption in public institutions continues to drain state resources, preventing effective use of funds for national development.

The Auditor General’s Department recently uncovered financial irregularities in several ministries, reinforcing concerns over systemic corruption.

Sectoral Allocations, Budget Inequities and Falures

Despite claims of prioritizing social welfare, the government’s budget allocation for key sectors remains insufficient. For example, while the government allocated LKR 500 million to improve 379 childcare centers nationwide, this amount pales in comparison to regional standards. In neighboring Bangladesh, the government spends around USD 60 per child annually, while Sri Lanka spends less than USD 25. It’s unclear whether this allocation represents an increase in funding or just a reshuffling of existing resources.

One of the biggest criticisms of the budget is its failure to address the high cost of essential goods, going against promises made during the election. Prices for basic items like rice and coconut are still high, due to supply chain issues, rising fuel costs, and tax policies. The absence of targeted subsidies or price controls has led to growing public dissatisfaction.

Public sector salary adjustments are also a point of contention. The government plans to introduce salary increases in three phases, with the full benefits expected by 2027. However, much of this increase was already granted in previous years through allowances, meaning the adjustment is more about restructuring existing funds than providing real pay increases. This slow approach raises concerns about whether employees’ purchasing power will improve, especially with inflation still a pressing issue.

The government has also urged the private sector to raise wages, but past experiences suggest that private companies often resist such requests. Without formal agreements or laws to enforce wage hikes, there is uncertainty over whether employees will see real wage growth that matches the rising cost of living.

Neglecting Vulnerable Workers and Obstinate Behaviour

Another group left out of the budget’s plans is casual and contract workers, who were expecting improvements in job security and wages, particularly those earning below LKR 1,800 per day. Despite promises made during the election, these workers have not seen any significant changes, which raises doubts about the government’s commitment to improving labor rights and income equality.

The government’s handling of private sector wage increases has also been criticized for a lack of transparency. In a televised discussion, A government representative became visibly agitated when questioned about the date of the agreement with employers, displaying obstinate behavior and refusing to answer the opposition MP’s inquiry.

Review of the Banking Sector’s Role in Govt. Revenue and Economic Growth

The banking sector helps generate national revenue through taxes such as corporate income tax, value-added tax (VAT), and financial transaction levies. However, the claim that it contributed 10% to government revenue in 2024 needs to be understood in context. Past figures have shown fluctuations in financial sector taxes, influenced by economic conditions and fiscal policies. The government’s growing reliance on the banking sector for tax revenue could signal financial stress, and this situation warrants further analysis to understand its long-term sustainability.

While the Sri Lanka Bankers Association (SLBA) emphasizes banks’ support for implementing the government’s budget proposals, their ability to do so effectively depends on broader economic conditions, regulations, and financial stability. Sri Lanka has faced persistent economic issues like high public debt and inflation, which could hamper the ability of banks to help implement fiscal policies effectively. The real impact of the banking sector in driving economic growth remains uncertain, especially given factors like currency instability and a lack of foreign investment.

Digitization and Financial Transparency

The proposal to introduce Point-of-Sale (POS) machines at VAT-registered businesses aligns with global trends in digital financial integration. This move is expected to improve transparency, reduce tax evasion, and increase banking efficiency. Research has shown that digital payments can boost financial inclusion and reduce informal economic activities. However, Sri Lanka faces challenges such as limited digital infrastructure, cybersecurity concerns, and resistance from businesses that still prefer cash transactions.

More digital services could strengthen anti-money laundering (AML) controls, improve transaction monitoring, and reduce cyber threats. However, shifting to a fully digital banking system requires substantial investments in technology, regulatory alignment, and digital literacy among consumers.

Support for SMEs and Development Banking Initiatives

The creation of a Credit Guarantee Institute for SMEs is a significant step. Research shows that credit guarantees can reduce lending risks and improve SME access to financing. However, past state-managed financial programs in Sri Lanka have been inefficient, often involving politicized lending practices.

For these new initiatives to succeed, they will need transparent governance, careful credit risk management, and strong regulations….

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s banking sector is crucial for economic stability and revenue generation, but the increasing fiscal demands and the push for digital transformation present both significant opportunities and risks. Policymakers need to avoid over-taxation that could stifle credit expansion and investment while addressing digital finance challenges like cybersecurity and infrastructure gaps. The 2025 budget underscores the nation’s vulnerable fiscal situation, where efforts for economic stabilization are hampered by public debt, corruption, and welfare constraints. Achieving sustainability requires comprehensive tax reforms, better public expenditure management, and stronger anti-corruption measures. Without these reforms, Sri Lanka faces prolonged economic hardship, rising inequalities, and diminishing trust in governance. The budget also reflects a blend of ideological transformation and economic pragmatism, with policies largely aligning with past approaches. Fitch Ratings’ cautious optimism signals the potential for recovery, contingent on successful policy implementation. Ultimately, policy continuity is seen as Sri Lanka’s best bet for navigating fiscal uncertainty and achieving economic stability.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Rethinking cities – Sustainable urban innovation

by Ifham Nizam

Dr. Nadeesha Chandrasena is an urban innovator reshaping the landscape of sustainable development. With a background that spans journalism, banking, and military engineering, she brings a unique perspective to urban planning and environmental resilience.

Her work integrates cutting-edge technology with human-centered design, ensuring that cities of the future are not only livable but also adaptive to climate change and rapid urbanisation.

In this interview with The Island, Dr. Chandrasena shares insights into her journey—from her early days in journalism to pioneering the Smart Drain Initiative, a groundbreaking infrastructure project addressing urban drainage inefficiencies. She discusses the critical role of community engagement, the challenges of balancing innovation with political realities, and the urgent need for sustainable urban solutions in Sri Lanka and beyond.

Her story is one of relentless curiosity, problem-solving, and a deep commitment to building better cities. As she puts it, “Urbanisation is inevitable; our challenge is to shape it in ways that are inclusive, sustainable, and forward-thinking.”

Urbanisation is one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, and few understand its complexities better than Dr. Chandrasena. A trailblazer in sustainable urban development, she has dedicated her career to bridging the gap between technological innovation and environmental sustainability. Through her work, she emphasises a crucial message: cities must evolve—not just grow.

From Journalism to Urban Innovation

Dr. Chandrasena’s career path is anything but conventional. Beginning as a journalist, she honed her skills in field research and community engagement, which later became instrumental in her work as an urban planner. “Journalism taught me how to listen to people’s stories and understand the realities on the ground,” she explains. This background helped her develop urban solutions rooted in real-world insights rather than abstract theories.

Her transition into urban innovation was fueled by a deep-seated passion for environmental resilience. After a stint in banking and serving in the Sri Lanka Army Corps of Engineers, she pursued town and country planning, ultimately integrating her diverse experiences to address urban challenges holistically.

The Smart Drain Initiative: A Game Changer in Urban Infrastructure

One of Dr. Chandrasena’s most groundbreaking contributions is the Smart Drain Initiative—a next-generation urban drainage system designed to combat flooding and waste accumulation. Implemented in areas like Balapola and Ambalangoda, this technology incorporates IoT-based monitoring, predictive maintenance, and automated waste filtration to enhance resilience against climate change.

“Storm drains are often neglected, but they are the foundation of a city’s flood resilience,” she says. By modernising drainage infrastructure, her initiative is setting a precedent for cities worldwide to rethink their approach to urban water management.

Livability as the Core Urban Challenge

For Dr. Chandrasena, urban planning is not just about infrastructure—it’s about people. She identifies livability as the root problem that must be addressed in city planning. “Congestion, pollution, lack of green spaces, and inefficient waste management are all symptoms of poor urban planning,” she explains. Her work focuses on designing cities that prioritise well-being, accessibility, and sustainability.

Sri Lanka, in particular, faces unique challenges due to rapid urbanisation. With cities like Colombo struggling to accommodate a massive influx of commuters, Dr. Chandrasena advocates for affordable housing solutions near economic hubs and improvements in public transportation. “A city’s economic success should not come at the cost of its residents’ quality of life,” she insists.

Technology and Community Engagement: The Future of Urban Development

Dr. Chandrasena sees technology as a powerful tool for fostering inclusive urban development. From using social media for community consultations to deploying smart infrastructure, she believes digital solutions can democratise urban planning. “We need to move beyond traditional engagement methods and empower people through accessible technology,” she says.

Her leadership philosophy reflects this inclusive approach. Through initiatives like the MyTurn Internship Platform, she mentors young professionals, encouraging them to take an active role in shaping the future of cities. “Leadership is not about authority—it’s about creating opportunities for collaboration,” she adds.

Global Urban Challenges and the Need for Collaboration

Urban issues are not confined to national borders. Dr. Chandrasena highlights the importance of global partnerships, citing the twin-city concept as a model for knowledge exchange. By pairing cities with similar challenges—such as Galle, Sri Lanka, and Penang, Malaysia—municipalities can co-create solutions that address both local and global urban challenges.

Her work has not gone unnoticed. She recently won Australia’s Good Design Award for Best in Class Engineering Design, a testament to the impact of her innovative approaches.

Call to Action for Sustainable Cities

Dr. Chandrasena’s vision for the future is clear: cities must be designed to be resilient, inclusive, and sustainable. While challenges like climate change and urban congestion persist, she remains optimistic. “There are no perfect cities—just as there are no perfect people. But by striving for practical solutions, we can make cities better for everyone.”

Her journey—from journalist to urban innovator—demonstrates that change begins with a vision and the determination to act on it. As urbanisation accelerates, her work serves as a blueprint for how cities can not only survive but thrive in an ever-evolving world.

Features

Need to appreciate SL’s moderate politics despite govt.’s massive mandate

by Jehan Perera

President Donald Trump in the United States is showing how, in a democratic polity, the winner of the people’s mandate can become an unstoppable extreme force. Critics of the NPP government frequently jibe at the government’s economic policy as being a mere continuation of the essential features of the economic policy of former president, Ranil Wickremesinghe. The criticism is that despite the resounding electoral mandates it received, the government is following the IMF prescriptions negotiated by the former president instead of making radical departures from it as promised prior to the elections. The critics themselves do not have alternatives to offer except to assert that during the election campaign the NPP speakers pledged to renegotiate the IMF agreement which they have done only on a very limited basis since coming to power.

There is also another area in which the NPP government is following the example of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe. During his terms of office, both as prime minister and president, Ranil Wickremesinghe ruled with a light touch. He did not utilise the might of the state to intimidate the larger population. During the post-Aragalaya period he did not permit street protests and arrested and detained those who engaged in such protests. At the same time with a minimal use of state power he brought stability to an unstable society. The same rule-with-a-light touch approach holds true of the NPP government that has succeeded the Wickremesinghe government. The difference is that President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has an electoral mandate that President Wickremesinghe did not have in his final stint in power and could use his power to the full like President Trump, but has chosen not to.

At two successive national elections, the NPP obtained the people’s mandate, and at the second one in particular, the parliamentary elections, they won an overwhelming 2/3 majority of seats. With this mandate they could have followed the “shock and awe” tactics that are being seen in the U.S. today under President Donald Trump whose party has won majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives. The U.S. president has become an unstoppable force and is using his powers to make dramatic changes both within the country and in terms of foreign relations, possibly irreversibly. He wants to make the U.S. as strong, safe and prosperous as possible and with the help of the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, the duo has become seemingly unstoppable in forging ahead at all costs.

EXTREME POWER

The U.S. has rightly been admired in many parts of the world, and especially in democratic countries, for being a model of democratic governance. The concepts of “checks and balances” and “separation of powers” by which one branch of the government restricts the power of the other branches appeared to have reached their highest point in the U.S. But this system does not seem to be working, at least at the present time, due to the popularity of President Trump and his belief in the rightness of his ideas and Elon Musk. The extreme power that can accrue to political leaders who obtain the people’s mandate can best be seen at the present time in the United States. The Trump administration is using the president’s democratic mandate in full measure, though for how long is the question. They have strong popular support within the country, but the problem is they are generating very strong opposition as well, which is dividing the U.S. rather than unifying it.

The challenge for those in the U.S. who think differently, and there are many of them at every level of society, is to find ways to address President Trump’s conviction that he has the right answers to the problems faced by the U.S. which also appears to have convinced the majority of American voters to believe in him. The decisions that President Trump and his team have been making to make the U.S. strong, safe and prosperous include eliminating entire government departments and dismissing employees at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) which were established to protect the more disadvantaged sectors of society. The targets have included USAID which has had consequences for Sri Lanka and many other disadvantaged parts of the world.

Data obtained from the Department of External Resources (ERD) reveal that since 2019, USAID has financed Sri Lankan government projects amounting to Rs. 31 billion. This was done under different presidents and political parties. Projects costing USD 20.4 million were signed during the last year (2019) of the Maithripala Sirisena government. USD 41.9 million was signed during the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government, USD 26 million during the Ranil Wickremesinghe government, and USD 18.1 million so far during the Anura Kumara Dissanayake government. At the time of the funding freeze, there were projects with the Justice Ministry, Finance Ministry, Environment Ministry and the Energy Ministry. This is apart from the support that was being provided to the private sector for business development and to NGOs for social development and good governance work including systems of checks and balances and separation of powers.

MODERATE POLITICS

The challenge for those in Sri Lanka who were beneficiaries of USAID is to find alternative sources of financing for the necessary work they were doing with the USAID funding. Among these was funding in support of improving the legal system, making digital technology available to the court system to improve case management, provision of IT equipment, and training of judges, court staff and members of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. It also included creating awareness about the importance of government departments delivering their services in an inclusive manner to all citizens requiring their services, and providing opportunities for inter-ethnic business collaboration to strengthen the economy. The government’s NGO Secretariat which has been asked to submit a report on USAID funding needs to find alternative sources of funding for these and give support to those who have lost their USAID funding.

Despite obtaining a mandate that is more impressive at the parliamentary elections than that obtained by President Trump, the government of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has been more moderate in its efforts to deal with Sri Lanka’s problems, whether in regard to the economy or foreign relations. The NPP government is trying to meet the interests of all sections of society, be they the business community, the impoverished masses, the civil society or the majority and minority ethnic and religious communities. They are trying to balance the needs of the people with the scarce economic resources at their disposal. The NPP government has demanded sacrifice of its own members, in terms of the benefits they receive from their positions, to correspond to the economic hardships that the majority of people face at this time.

The contrast between the governance styles of President Trump in the U.S. and President Dissanayake in Sri Lanka highlights the different paths democratic leaders can take. President Trump is attempting to decisively reshape the U.S. foreign policy, eliminating entire government departments and overwhelming traditional governance structures. The NPP government under President Dissanayake has sought a more balanced, inclusive path by taking steps to address economic challenges and governance issues while maintaining stability. They are being tough where they need to be, such as on the corruption and criminality of the past. They need to be supported as they are showing Sri Lankans and the international community how a government can use its mandate without polarising society and thereby securing the consensus necessary for sustainable change.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCourtroom shooting: Police admit serious security lapses

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoUnderworld figure ‘Middeniye Kajja’ and daughter shot dead in contract killing

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoKiller made three overseas calls while fleeing

-

Features3 days ago

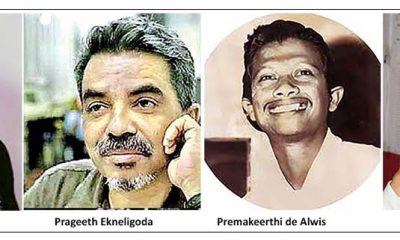

Features3 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSC notices Power Minister and several others over FR petition alleging govt. set to incur loss exceeding Rs 3bn due to irregular tender