Features

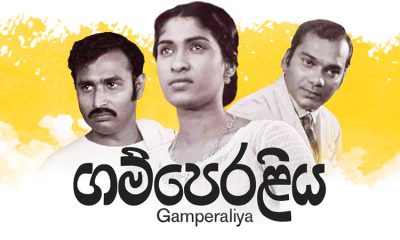

The Popular Sinhala Cinema : Rukmani Devi; Mohideen Baig ; Gamini Fonseka

by Laleen Jayamanne

Rukmani Devi, the first star of the Sinhala cinema and incomparable singer with a unique voice, originally known as Daisy Rasamma Daniel, was a Tamil Christian. It was well known that she couldn’t read or write Sinhala and that her dialogue and lyrics were written in English. Al-Haj Mohideen Baig, who sang some of the most cherished, perennial popular Sinhala film songs (including Budhu Gee), wrote down the Sinhala lyrics in his mother tongue, Urdu. The multilingual Mohideen Baig came to Lanka in 1932 for his brother’s funeral and stayed on. With the guidance of Mohammed Gauss at Columbia records, he began singing on radio soon after. In India he had sung Ghazals in Urdu in his village Salem and also Hindi and Tamil songs.

Once film production began in Lanka, he had a long career as a backup singer, starting with Asokamala (1947). His powerful, textured voice was unique just like Rukmani Devi’s, which made their songs immensely popular. Also, he acted as a beggar in Sujatha (53), walking across landscapes, singing melancholy shoka gee, commenting on the action. His love songs with Rukmani Devi are some of the most heartfelt songs of longing (viraha), in films like Nalagana (1960), which I heard as a child, at the proletarian Gamini theatre Maradana, where their songs blared out vibrating the small theatre and our hearts. Listening to the songs now on YouTube, those memories flood my thoughts (as I write), as only music can, though the films themselves are a faint memory. Gamini was among several Tamil owned cinemas burned down in July 83 race riots.

Here, I wish focus on Rukmani Devi and Baig Master’s careers within the multi-ethnic composition of the Lankan film industry. Gamini Fonseka will make a guest appearance here as a trilingual Sinhala star who built a Tamil fan base. I examine the period from Rukmani Devi’s starring role in the very first Sinhala film Kadawuna Produwa (Broken Promise) in 1947, going beyond her accidental tragic death in 1978, to the murdering of the director K. Vanket in July 83, and concluding with the assassination of the pioneering film producer and entrepreneur, K. Gunaratnam in 1989, by a JVP gunman.

I do this so as to understand anew the cultural value of the early Lankan hybrid popular cinema and its cross-cultural heritage of songs, its multi-ethnic history, through reading and listening carefully to several of its most ardent cinephiles and researchers. They are a group of older, now retired journalists who are in fact the first generation of Sinhala cinephiles and writers of the Lankan cinema, such as A.D. Ranjith Kumara, Sunil Mihindukula former editors of Saraswiya, Ranjan de Silva, Ananda Padmasiri and Ariyasiri Withanage, who have conducted research into those critically maligned early films, their songs and the mass audience and have helped create a film culture through their writing and programming of film songs.

As cinephiles and collectors, their passion for that popular cinema of the past remains undiminished even in retirement. I came across them through a series of informative programmes on Independent Television Network (ITN), directed by Indrasiri Suraweera (available on YouTube). Their careful historical research into the musical traditions of the films, and generosity of spirit should inspire younger generations of critics and intellectuals to do more historical and theoretical work on the Lankan cinema more broadly and not forget its hybrid foundations. It is a cinema I enjoyed as a child, but studied critically while writing my doctorate on female representation in these films. Also, because most of these men were trained as journalists on radio and the print media, they are highly disciplined concise speakers (unlike us verbose academics), so it was a pleasure to listen to them exploring an undervalued period of Lankan mass cultural history. This history has an important relationship to Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism and its relation to the ethnic minorities of the country as well.

A Feminist Perspective on Rukmani Devi’s Career

Rukmani Devi died in a car crash in the early hours of one morning in October 1978. She had been travelling all night from Matara to Negombo, after having sung at a carnival variety show there. While there are numerous accounts of her death in all its detail and of the mass funeral and public mourning recorded on film, there is no discussion of why she was travelling such a long distance all night, from Matara to Negombo, after a ‘hard day’s work…’. As far as I know there is no critical analysis of what happened to her career at midlife and how that might have had some connection to the circumstances leading to that fatal accident. Her career trajectory from super-stardom as both an actress and singer from the 1940s, mingling with political and business leaders and some of the major Indian film stars, appearing on the cover of the Indian film magazine Film Fare, and a long recording and singing career, starting as a girl, from 1938, to end up singing in a variety show down South, is surely an index of the precariousness of her life. Her financial insecurity was also true of the lives of many other people who had worked in the film industry (including technicians, directors, main and supporting actors), in the first decades of Lankan cinema. This dark history should also be included as an essential part of what is often referred to (with pride), by some Sinhala critics as, Sinhala sinamawe wansa kathawa (the illustrious genealogy of the Sinhala cinema).

That Rukmani Devi lived an independent personal life as a professional woman in Lanka, starting quite young as an actress, on stage and film in the late 1940s, strikes me as an important aspect of her career, though the roles available to her on film reinforced feudal patriarchal values. The film Samiya Birindage Deviyaya (The Husband is the Wife’s God, 1963, WMS Tampo), stands as one of the most extreme examples of these oppressive values. It’s been referred to as a ‘women’s picture’, one which ‘they like to watch crying’, said one Sinhala male critic. Hollywood called their version ‘the weepies’, a profitable melodramatic genre targeting the new female spectator-consumer, who attended matinees.

The panellists, Ranjith Kumara has written a book on Rukmani Devi and Ranjan de Silva is a collector of her gramophone records and the song sheets of that era. He is also knowledgeable about Indian musical traditions such as the Raga based Hindustani music and popular Bajan and Ghazal songs for instance. He could hear their precise influences on the best of the early Sinhala film songs and how the originals were adapted and modified, rather than simply copied in the best examples. Appreciating the high quality of the Indian originals, he didn’t simply dismiss the early songs as ‘bad’ just because their origins were ‘Indian’.

His ideas on adaptation are sophisticated and can be used to revise dogmatic views on the early film songs. Most entries on the web simply list Rukmani Devi’s’ films with plot summaries without an analysis of her roles, some even extending her film list to dates well after her death, perhaps their dates of exhibition!

I can find no discussion on how her career ended in sharp decline, and what that means about the economically precarious state of some of the personnel, both men and women in the film industry of that time. There is plenty of adulation and appreciation of Rukmani Devi now as a singer, especially at anniversaries. People still listen to her songs and know her ‘legend’, and sing her songs, but with voices that are very high-pitched and ‘thin’, without her rich timbre nor the wide range of her voice and intensity of feeling. These innate qualities prompted one critic to suggest that she might have been able to sing Western opera as well. There is an unfortunate absence of an account of her as a pioneering female professional actress and singer, the challenges she faced (as a modern high profiled Tamil woman), all of which I think merit research, especially by feminist scholars and critics.

A useful thesis or two may be formulated and written on this and related topics at one of our universities. The existing research by Ranjith Kumara and Ranjan de Silva and younger critics and researchers should be drawn on and extended from a feminist perspective on ‘women and work’ and ‘female representation’ on film. There are a few books written by these older cinephiles, which must be collectors’ items by now. There is a small book by Sarath Ranaweera on Master Baig.

The fact that Rukmani Devi returned to the stage to perform in Dhamma Jargoda’s Vesmuhunu (an adaptation of A street car named desire by Tennessee Williams), either in 69 or 70, was mentioned by Ranjith Kumara, along with a significant anecdote. He said that just before she went on stage to perform as an aristocratic lady (originally Blanche du Bois in Williams’ play), she had insisted on showing her respect to Dhamma in the traditional Sinhala manner of bowing to him by going down on her hands and knees at his feet.

Ranjith Kumara mentions this because, as he rightly says, it was an unusual gesture for a Christian such as Rukmani Devi to perform. Certainly, in our catholic villages, stretching from Uswatakeiyawa to Negombo (Rukmani’s home town with Eddy Jayamanne), there was never such a practice and it still remains quite a foreign gesture to me, though I do appreciate the idea of ‘guru bhakti’ which encodes Rukmani Devi’s gesture. Ranjith Kumara elaborates on this, saying that it was Dhamma’s Shilpiya manasa (artistic intelligence) that Rukmani bowed to. One could take up this fascinating anecdote, told with such perspicacity, a little further.

Cultural Capital: Rukmani Devi and Irangani Serasinghe

I happened to have seen some of the rehearsals of Dhamma’s Vesmuhunu, as an inaugural student of the Art Centre Theatre Studio of 1970/71. If I remember right, Dhamma also did a version of it with Irangani Serasinghe simultaneously, alternating between these two brilliant Lankan actors. Some of us saw both rehearsals in Harrold Peiris’s large open garage at Alfred House, where our workshops were held, before the Lionel Wendt complex was refurbished to house the workshop. So, Rukmani’s unusual gesture of gratitude to Dhamma, I imagine, is because someone of his stature in Lankan theatre had finally given her the gift of playing a serious dramatic role in a modern play. The actress who started her career in the popular Tower Hall Nurti plays of the 40s and the Minerva theatre of B.A.W. Jayamanne, was finally given the opportunity to act in a modern western classic. Kumara also mentioned how much Rukmani Devi appreciated being able to act in Lester James Peries’ Ahasin Polowata (From the Sky to the Earth) where the Nimal Mendis song she sang won her a posthumous award.

There are several other famous global super stars who have yearned recognition and respect as ‘serious’ actors. The most famous of course being Marlin Monroe who produced The Prince and the Showgirl just so she could act with the famous British Shakespearean actor, Lawrence Olivier, while she was still married to Arthur Miller the famous American playwright. For unusually gifted super stars such as these, popularity alone is insufficient, knowing full well how ephemeral, limited and confining their popular ‘sexy’ image is for them, they longed for something more durable to work on, something with cultural and intellectual capital, one might now say.

Perhaps reading Rukmani’s autobiography (Mage Jeevitha Vitti), might provide more leads into the intricate intersections between her life and work, which in her case are especially inseparable, unlike that of any other Lankan film star I know of. Her use of the word ‘vitti’ (information), rather than ‘katha’ (story) suggests that she knew how to protect herself, her privacy. Rukmani Devi’s career started with her elopement and marriage, while still a minor, and she never stopped working in the dominant language which was not her mother tongue, having done only a few performances in Tamil. Whereas, many Lankan Sinhala female stars have left their careers at the height of their popularity to get married and have a family. Most memorably Jeevarani Kurukulasuriya (who formed such a popular romantic duo with Gamini Fonseka, our first male action hero), abandoned her career at marriage.

Dharmasena Pathiraja’s comments, at the official celebration held by the then president Maithripala Sirisena (along with the former president Chandrika Bandaranayaka), to mark the 50th anniversary of his professional work in the Lankan film industry, are relevant in thinking about Rukmani Devi’s predicament. He undercut the idea that he had worked ‘professionally’ in the ‘Lankan film industry’. He asked, rhetorically but politely:

“What Industry? How can there be an industry without capital, if there is no professional stability and proper infrastructure? When we look at the sad last days of Rukmani Devi, Domi Jayawardhana and Eddie Jayamanne, how can we speak of an industry? I wasn’t a filmmaker professionally, was anyone able to make a living professionally? I made a living by teaching as a lecturer from 1968-2008. (Maha lokuwata, arambaye sita karmanthayak gana katha keruwath, ape athdakeema anuwa wurthiya sthawarathwayk nathnam kohomada karmanthayak thienne!) The people who say there is an industry are the exhibitors and some producers.”

These starkly realist comments may be taken as an important starting point for future research into the economic, cultural and biographical histories of stars of the Lankan cinema, by young scholars. Clearly, Pathiraja knew from within what exactly had happened to these once very popular actors late in their lives. Perhaps it’s not too late yet to do some oral history before those with personal memory and deep knowledge of the vital early decades also pass away.

I remember visiting Master Hugo Fernando (who did comic routines with his little knot of hair tied at the back and large umbrella tucked under his arm), to talk about the ethos of the old days, which he did so graciously. Kumara and de Silva’s research is indispensable in this regard. Irangani Serasinghe would probably welcome a chance to talk about working with both Dhamma and Rukmani on the same play simultaneously, a most unusual experiment only he could have devised. I feel, in doing so, he was paying homage to two of Lanka’s uniquely popular actors from vastly different social worlds and actorly traditions, with very different cultural capital.

There is a strange symmetry in their career trajectories, but going in opposite directions. Irangani became a beloved house hold name only after the advent of the teledramas once Television was introduced in the late 70s. Prior to that, her acting began at the University Dram Soc where she famously played the heroine in the Greek classic Antigone. After her training at Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, she acted in the English language theatre and in the films of Lester beginning with Rekava (1956). Her repertoire included Shakespeare, Chekov, Lorca, Brecht and others. This also led her to play in Sinhala theatre as well.

During this time, she was recognised as one of our finest actors in both languages, but was not a household name as her work was consistently on the English stage. In contrast, Rukmani was a national figure of great adoration as an actress and singer on film and radio starting from the 40s. While Irangani worked in the domain of high-culture, Rukmani Devi created a Lankan popular mass culture (with Master Baig and others), through her films and songs. But with each change of taste, fashion and the fact of ageing, her film appeal diminished. But her resilience at self-reinvention is evident when she joined the group Los Cabelleros, singing Sinhala pop songs to Latin rhythms, with a show in Jaffna where she sang in Tamil.

I wonder if her Sinhala fans were curious enough to ask her to sing in Tamil as well. In her later years she longed to perform in work that was considered intellectually serious, engaged art. And this chance she did get but belatedly with Dhamma, while Irangani, through her later work in tele-dramas and films, has been able to continue her career well into her 90s and also become a cherished ‘national treasure’. Just as some critics dismissed the early Sinhala films dependent on Indian models, there are those who are critical of many teledramas for their low quality and diluting of popular taste and powers of discrimination. Unlike Irangani’s, Rukmani’s career trajectory marks a sad decline, as Pathiraja stated so forcefully. Therefore, all the massive outpouring of love and grief at her death is no compensation for the loss of worthwhile work. After all she died at only 55 with so much untapped creativity still left.

I am not alone in thinking that Lanka failed this rare artist of national and international stature, as it did Master Mohideen Baig (but more of him later). A visiting Indian star on hearing Rukmani Devi sing had said that, had she been born in India she would have been far more famous. Perhaps like the iconic singer Latha Mangeshkar, of whom Kumar Shahani once said: ‘If India has a heart, then that would be Latha Mangeshkar.’ Singing melancholy songs (Shoka Geetha), but with poetic lyrics written especially for her in Tamil and Sinhala, Rukmani Devi might have become, for all of us, (irrespective of our ethnic differences), Lanka’s sole soulful female voice. Baig Master was the only singer who sang with Mangeshkar, who also sang a song in Sinhala.

Rukmani Devi’s unerring ear meant that she could ‘pass’ as Sinhala, without a trace of her Tamil mother tongue inflecting her enunciation of the words. This ability was not a matter of aesthetics alone within the history of race relations in modern Sri Lanka, then Ceylon. In fact, the ability to pronounce ‘correctly’ the Sinhala word for bucket as ‘baldi’, became a sign of one’s ethnic identity during anti-Tamil riots in July 83. Saying ‘valdi’ instead of ‘baldi’ resulted even in death.

Mohideen Baig, a Muslim, who sang duets with Rukmani Devi, did so with a slight Urdu inflected accent and yet he was an essential part of Sinhala cinema and radio with mass appeal for much of the early period. Together, they evoked a haunting feeling of pathos tinged with a melancholy mood (viraha), in many of their songs, most especially in Jeevana me gamana sansare (samsare of this life’s journey).

Muttusamy and Rocksamy were the leading composers of music for the songs in Sinhala, though there were many other Tamil and Muslim musicians working in the industry as well. Even after better educated writers of lyrics entered the industry these highly skilled musicians continued to compose for them. For example, while Karunaratna Abeysekara wrote the lyrics for Kurul Badda the music was by Muttusamy. Rocksamy composed the music for Dharmasena Pathiraja’s great Tamil language film Ponmani, a truly innovative score in that the main song in the Karnataka idiom is repeated as a refrain, creating an emotional commentary on the main violent action. He also played the saxophone which was banned by the Sinhala nationalists at Radio Ceylon as being a brass Western instrument!

To be continued…

Features

Building on Sand: The Indian market trap

(Part III in a series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation.)

Every SLTDA (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority) press release now leads with the same headline: India is Sri Lanka’s “star market.” The numbers seem to prove it, 531,511 Indian arrivals in 2025, representing 22.5% of all tourists. Officials celebrate the “half-million milestone” and set targets for 600,000, 700,000, more.

Every SLTDA (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority) press release now leads with the same headline: India is Sri Lanka’s “star market.” The numbers seem to prove it, 531,511 Indian arrivals in 2025, representing 22.5% of all tourists. Officials celebrate the “half-million milestone” and set targets for 600,000, 700,000, more.

But follow the money instead of the headcount, and a different picture emerges. We are building our tourism recovery on a low-spending, short-stay, operationally challenging segment, without any serious strategy to transform it into a high-value market. We have confused market size with market quality, and the confusion is costing us billions.

Per-day spending: While SLTDA does not publish market-specific daily expenditure data, industry operators and informal analyses consistently report Indian tourists in the $100-140 per day range, compared to $180-250 for Western European and North American markets.

The math is brutal and unavoidable: one Western European tourist generates the revenue of 3-4 Indian tourists. Building tourism recovery primarily on the low-yield segment is strategically incoherent, unless the goal is arrivals theater rather than economic contribution.

Comparative Analysis: How Competitors Handle Indian Outbound Tourism

India is not unique to Sri Lanka. Indian outbound tourism reached 30.23 million departures in 2024, an 8.4% year-on-year increase, driven by a growing middle class with disposable income. Every competitor destination is courting this market.

This is not diversification. It is concentration risk dressed up as growth.

How did we end up here? Through a combination of policy laziness, proximity bias, and refusal to confront yield trade-offs.

1. Proximity as Strategy Substitute

India is next door. Flights are short (1.5-3 hours), frequent, and cheap. This makes India the easiest market to attract, low promotional cost, high visibility, strong cultural and linguistic overlap. But easiest is not the same as best.

Tourism strategy should optimize for yield-adjusted effort. Yes, attracting Europeans requires longer promotional cycles, higher marketing spend, and sustained brand-building. But if each European generates 3x the revenue of an Indian tourist, the return on investment is self-evident.

We have chosen ease over effectiveness, proximity over profitability.

2. Visa Policy as Blunt Instrument

3. Failure to Develop High-Value Products for Indian Market

There are segments of Indian outbound tourism that spend heavily:

* Wedding tourism: Indian destination weddings can generate $50,000-200,000+ per event

* Wellness/Ayurveda tourism: High-net-worth Indians seek authentic wellness experiences and will pay premium rates

* MICE tourism: Corporate events, conferences, incentive travel

Sri Lanka has these assets—coastal venues for weddings, Ayurvedic heritage, colonial hotels suitable for corporate events. But we have not systematically developed and marketed these products to high-yield Indian segments.

For the first time in 2025, Sri Lanka conducted multi-city roadshows across India to promote wedding tourism. This is welcome—but it is 25 years late. The Maldives and Mauritius have been curating Indian wedding and MICE tourism for decades, building specialised infrastructure, training staff, and integrating these products into marketing.

We are entering a mature market with no track record, no specialised infrastructure, and no price positioning that signals premium quality.

4. Operational Challenges and Quality Perceptions

Indian tourists, particularly budget segments, present operational challenges:

* Shorter stays mean higher turnover, more check-ins, more logistical overhead per dollar of revenue

* Price sensitivity leads to aggressive bargaining, complaints over perceived overcharging

* Large groups (families, wedding parties) require specialised handling

None of these are insurmountable, but they require investment in training, systems, and service design. Sri Lanka has not made these investments systematically. The result: operators report higher operational costs per Indian guest while generating lower revenue, a toxic margin squeeze.

Additionally, Sri Lanka’s positioning as a “budget-friendly” destination reinforces price expectations. Indians comparing Sri Lanka to Thailand or Malaysia see Sri Lanka as cheaper, not better. We compete on price, not value, a race to the bottom.

The Strategic Error: Mistaking Market Size for Market Fit

India’s outbound tourism market is massive, 30 million+ and growing. But scale is not the same as fit.

Market size ≠ market value: The UAE attracts 7.5 million Indians, but as a high-yield segment (business, luxury shopping, upscale hospitality). Saudi Arabia attracts 3.3 million—but for religious pilgrimage with high per-capita spending and long stays.

Thailand attracts 1.8 million Indians as part of a diversified 35-million-tourist base. Indians represent 5% of Thailand’s mix. Sri Lanka has made Indians 22.5% of our mix, 4.5 times Thailand’s concentration, while generating a fraction of Thailand’s revenue.

This reveals the error. We have prioritised volume from a market segment without ensuring the segment aligns with our value proposition.

These needs are misaligned. Indians seek budget value; Sri Lanka needs yield. Indians want short trips; Sri Lanka needs extended stays. Indians are price-sensitive; Sri Lanka needs premium segments to fund infrastructure.

We have attracted a market that does not match our strategic needs—and then celebrated the mismatch as success.

The Way Forward: From Dependency to Diversification

Fixing the Indian market trap requires three shifts: curation, diversification, and premium positioning.

First

, segment the Indian market and target high-value niches explicitly:

, segment the Indian market and target high-value niches explicitly:

* Wedding tourism: Develop specialised wedding venues, train planners, create integrated packages ($50k+ per event)

* Wellness tourism: Position Sri Lanka as authentic Ayurveda destination for high-net-worth health seekers

* MICE tourism: Target Indian corporate incentive travel and conferences

* Spiritual/religious tourism: Leverage Buddhist and Hindu heritage sites with premium positioning

Market these high-value niches aggressively. Let budget segments self-select out through pricing signals.

Second

, rebalance market mix toward high-yield segments:

* Increase marketing spend on Western Europe, North America, and East Asian premium segments

* Develop products (luxury eco-lodges, boutique heritage hotels, adventure tourism) that appeal to high-yield travelers

* Use visa policy strategically, maintain visa-free for premium markets, consider tiered visa fees or curated visa schemes for volume markets

Third

, stop benchmarking success by Indian arrival volumes. Track:

* Revenue per Indian visitor

* Indian market share of total revenue (not arrivals)

* Yield gap: Indian revenue vs. other major markets

If Indians are 22.5% of arrivals but only 15% of revenue, we have a problem. If the gap widens, we are deepening dependency on a low-yield segment.

Fourth

, invest in Indian market quality rather than quantity:

* Train staff on Indian high-end expectations (luxury service standards, dietary needs)

* Develop bilingual guides and materials (Hindi, Tamil)

* Build partnerships with premium Indian travel agents, not budget consolidators

We should aim to attract 300,000 Indians generating $1,500 per trip (through wedding, wellness, MICE targeting), not 700,000 generating $600 per trip. The former produces $450 million; the latter produces $420 million, while requiring more than twice the operational overhead and infrastructure load.

Fifth

, accept the hard truth: India cannot and should not be 30-40% of our market mix. The structural yield constraints make that model non-viable. Cap Indian arrivals at 15-20% of total mix and aggressively diversify into higher-yield markets.

This will require political courage, saying “no” to easy volume in favour of harder-won value. But that is what strategy means: choosing what not to do.

The Dependency Trap

Every market concentration creates path dependency. The more we optimize for Indian tourists, visa schemes, marketing, infrastructure, pricing, the harder it becomes to attract high-yield markets that expect different value propositions.

Hotels that compete on price for Indian segments cannot simultaneously position as luxury for European segments. Destinations known for “affordability” struggle to pivot to premium. Guides trained for high-turnover, short-stay groups do not develop the deep knowledge required for extended cultural tours.

We are locking in a low-yield equilibrium. Each incremental Indian arrival strengthens the positioning as a “budget-friendly” destination, which repels high-yield segments, which forces further volume-chasing in price-sensitive markets. The cycle reinforces itself.

Breaking the cycle requires accepting short-term pain—lower arrival numbers—for long-term gain—higher revenue, stronger positioning, sustainable margins.

The Hard Question

Is Sri Lanka willing to attract two million tourists generating $5 billion, or three million tourists generating $4 billion?

The current trajectory is toward the latter, more arrivals, less revenue, thinner margins, greater fragility. We are optimizing for metrics that impress press releases but erode economic contribution.

The Indian market is not the problem. The problem is building tourism recovery primarily on a low-yield segment without strategies to either transform that segment to high-yield or balance it with high-yield markets.

We are building on sand. The foundation will not hold.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Digital transformation in the Global South

Understanding Sri Lanka through the India AI Impact Summit 2026

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly moved from being a specialised technological field into a major social force that shapes economies, cultures, governance, and everyday human life. The India AI Impact Summit 2026, held in New Delhi, symbolised a significant moment for the Global South, especially South Asia, because it demonstrated that artificial intelligence is no longer limited to advanced Western economies but can also become a development tool for emerging societies. The summit gathered governments, researchers, technology companies, and international organisations to discuss how AI can support social welfare, public services, and economic growth. Its central message was that artificial intelligence should be human centred and socially useful. Instead of focusing only on powerful computing systems, the summit emphasised affordable technologies, open collaboration, and ethical responsibility so that ordinary citizens can benefit from digital transformation. For South Asia, where large populations live in rural areas and resources are unevenly distributed, this idea is particularly important.

People friendly AI

One of the most important concepts promoted at the summit was the idea of “people friendly AI.” This means that artificial intelligence should be accessible, understandable, and helpful in daily activities. In South Asia, language diversity and economic inequality often prevent people from using advanced technology. Therefore, systems designed for local languages, and smartphones, play a crucial role. When a farmer can speak to a digital assistant in Sinhala, Tamil, or Hindi and receive advice about weather patterns or crop diseases, technology becomes practical rather than distant. Similarly, voice based interfaces allow elderly people and individuals with limited literacy to use digital services. Affordable mobile based AI tools reduce the digital divide between urban and rural populations. As a result, artificial intelligence stops being an elite instrument and becomes a social assistant that supports ordinary life.

Transformation in education sector

The influence of this transformation is visible in education. AI based learning platforms can analyse student performance and provide personalised lessons. Instead of all students following the same pace, weaker learners receive additional practice while advanced learners explore deeper material. Teachers are able to focus on mentoring and explanation rather than repetitive instruction. In many South Asian societies, including Sri Lanka, education has long depended on memorisation and private tuition classes. AI tutoring systems could reduce educational inequality by giving rural students access to learning resources, similar to those available in cities. A student who struggles with mathematics, for example, can practice step by step exercises automatically generated according to individual mistakes. This reduces pressure, improves confidence, and gradually changes the educational culture from rote learning toward understanding and problem solving.

Healthcare is another area where AI is becoming people friendly. Many rural communities face shortages of doctors and medical facilities. AI-assisted diagnostic tools can analyse symptoms, or medical images, and provide early warnings about diseases. Patients can receive preliminary advice through mobile applications, which helps them decide whether hospital visits are necessary. This reduces overcrowding in hospitals and saves travel costs. Public health authorities can also analyse large datasets to monitor disease outbreaks and allocate resources efficiently. In this way, artificial intelligence supports not only individual patients but also the entire health system.

Agriculture, which remains a primary livelihood for millions in South Asia, is also undergoing transformation. Farmers traditionally rely on seasonal experience, but climate change has made weather patterns unpredictable. AI systems that analyse rainfall data, soil conditions, and satellite images can predict crop performance and recommend irrigation schedules. Early detection of plant diseases prevents large-scale crop losses. For a small farmer, accurate information can mean the difference between profit and debt. Thus, AI directly influences economic stability at the household level.

Employment and communication reshaped

Artificial intelligence is also reshaping employment and communication. Routine clerical and repetitive tasks are increasingly automated, while demand grows for digital skills, such as data management, programming, and online services. Many young people in South Asia are beginning to participate in remote work, freelancing, and digital entrepreneurship. AI translation tools allow communication across languages, enabling businesses to reach international customers. Knowledge becomes more accessible because information can be summarised, translated, and explained instantly. This leads to a broader sociological shift: authority moves from tradition and hierarchy toward information and analytical reasoning. Individuals rely more on data when making decisions about education, finance, and career planning.

Impact on Sri Lanka

The impact on Sri Lanka is especially significant because the country shares many social and economic conditions with India and often adopts regional technological innovations. Sri Lanka has already begun integrating artificial intelligence into education, agriculture, and public administration. In schools and universities, AI learning tools may reduce the heavy dependence on private tuition and help students in rural districts receive equal academic support. In agriculture, predictive analytics can help farmers manage climate variability, improving productivity and food security. In public administration, digital systems can speed up document processing, licensing, and public service delivery. Smart transportation systems may reduce congestion in urban areas, saving time and fuel.

Economic opportunities are also expanding. Sri Lanka’s service based economy and IT outsourcing sector can benefit from increased global demand for digital skills. AI-assisted software development, data annotation, and online service platforms can create new employment pathways, especially for educated youth. Small and medium entrepreneurs can use AI tools to design products, manage finances, and market services internationally at low cost. In tourism, personalised digital assistants and recommendation systems can improve visitor experiences and help small businesses connect with travellers directly.

Digital inequality

However, the integration of artificial intelligence also raises serious concerns. Digital inequality may widen if only educated urban populations gain access to technological skills. Some routine jobs may disappear, requiring workers to retrain. There are also risks of misinformation, surveillance, and misuse of personal data. Ethical regulation and transparency are, therefore, essential. Governments must develop policies that protect privacy, ensure accountability, and encourage responsible innovation. Public awareness and digital literacy programmes are necessary so that citizens understand both the benefits and limitations of AI systems.

Beyond economics and services, AI is gradually influencing social relationships and cultural patterns. South Asian societies have traditionally relied on hierarchy and personal authority, but data-driven decision making changes this structure. Agricultural planning may depend on predictive models rather than ancestral practice, and educational evaluation may rely on learning analytics instead of examination rankings alone. This does not eliminate human judgment, but it alters its basis. Societies increasingly value analytical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Educational systems must, therefore, move beyond memorisation toward critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning.

AI contribution to national development

In Sri Lanka, these changes may contribute to national development if implemented carefully. AI-supported financial monitoring can improve transparency and reduce corruption. Smart infrastructure systems can help manage transportation and urban planning. Communication technologies can support interaction among Sinhala, Tamil, and English speakers, promoting social inclusion in a multilingual society. Assistive technologies can improve accessibility for persons with disabilities, enabling broader participation in education and employment. These developments show that artificial intelligence is not merely a technological innovation but a social instrument capable of strengthening equality when guided by ethical policy.

Symbolic shift

Ultimately, the India AI Impact Summit 2026 represents a symbolic shift in the global technological landscape. It indicates that developing nations are beginning to shape the future of artificial intelligence according to their own social needs rather than passively importing technology. For South Asia and Sri Lanka, the challenge is not whether AI will arrive but how it will be used. If education systems prepare citizens, if governments establish responsible regulations, and if access remains inclusive, AI can become a partner in development rather than a source of inequality. The future will likely involve close collaboration between humans and intelligent systems, where machines assist decision making while human values guide outcomes. In this sense, artificial intelligence does not replace human society, but transforms it, offering Sri Lanka an opportunity to build a more knowledge based, efficient, and equitable social order in the decades ahead.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Features

Governance cannot be a postscript to economics

The visit by IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva to Sri Lanka was widely described as a success for the government. She was fulsome in her praise of the country and its developmental potential. The grounds for this success and collaborative spirit go back to the inception of the agreement signed in March 2023 in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s declaration of international bankruptcy. The IMF came in to fulfil its role as lender of last resort. The government of the day bit the bullet. It imposed unpopular policies on the people, most notably significant tax increases. At a moment when the country had run out of foreign exchange, defaulted on its debt, and faced shortages of fuel, medicine and food, the IMF programme restored a measure of confidence both within the country and internationally.

Since 1965 Sri Lanka has entered into agreements with the IMF on 16 occasions none of which were taken to their full term. The present agreement is the 17th agreement . IMF agreements have traditionally been focused on economic restructuring. Invariably the terms of agreement have been harsh on the people, with priority being given to ensure the debtor country pays its loans back to the IMF. Fiscal consolidation, tax increases, subsidy reductions and structural reforms have been the recurring features. The social and political costs have often been high. Governments have lost popularity and sometimes fallen before programmes were completed. The IMF has learned from experience across the world that macroeconomic reform without social protection can generate backlash, instability and policy reversals.

The experience of countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal in dealing with the IMF during the eurozone crisis demonstrated the political and social costs of austerity, even though those economies later stabilised and returned to growth. The evolution of IMF policies has ensured that there are two special features in the present agreement. The first is that the IMF has included a safety net of social welfare spending to mitigate the impact of the austerity measures on the poorest sections of the population. No country can hope to grow at 7 or 8 percent per annum when a third of its people are struggling to survive. Poverty alleviation measures in the Aswesuma programme, developed with the agreement of the IMF, are key to mitigating the worst impacts of the rising cost of living and limited opportunities for employment.

Governance Included

The second important feature of the IMF agreement is the inclusion of governance criteria to be implemented alongside the economic reforms. It goes to the heart of why Sri Lanka has had to return to the IMF repeatedly. Economic mismanagement did not take place in a vacuum. It was enabled by weak institutions, politicised decision making, non-transparent procurement, and the erosion of checks and balances. In its economic reform process, the IMF has included an assessment of governance related issues to accompany the economic restructuring process. At the top of this list is tackling the problem of corruption by means of publicising contracts, ensuring open solicitation of tenders, and strengthening financial accountability mechanisms.

The IMF also encouraged a civil society diagnostic study and engaged with civil society organisations regularly. The civil society analysis of governance issues which was promoted by Verite Research and facilitated by Transparency International was wider in scope than those identified in the IMF’s own diagnostic. It pointed to systemic weaknesses that go beyond narrow fiscal concerns. The civil society diagnostic study included issues of social justice such as the inequitable impact of targeting EPF and ETF funds of workers for restructuring and the need to repeal abuse prone laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Online Safety Act. When workers see their retirement savings restructured without adequate consultation, confidence in policy making erodes. When laws are perceived to be instruments of arbitrary power, social cohesion weakens.

During a meeting between the IMF Managing Director Georgeiva and civil society members last week, there was discussion on the implementation of those governance measures in which she spoke in a manner that was not alien to the civil society representatives. Significantly, the civil society diagnostic report also referred to the ethnic conflict and the breakdown of interethnic relations that led to three decades of deadly war, causing severe economic losses to the country. This was also discussed at the meeting. Governance is not only about accounting standards and procurement rules. It is about social justice, equality before the law, and political representation. On this issue the government has more to do. Ethnic and religious minorities find themselves inadequately represented in high level government committees. The provincial council system that ensured ethnic and minority representation at the provincial level continues to be in abeyance.

Beyond IMF

The significance of addressing governance issues is not only relevant to the IMF agreement. It is also important in accessing tariff concessions from the European Union. The GSP Plus tariff concession given by the EU enables Sri Lankan exports to be sold at lower prices and win markets in Europe. For an export dependent economy, this is critical. Loss of such concessions would directly affect employment in key sectors such as apparel. The government needs to address longstanding EU concerns about the protection of human rights and labour rights in the country. The EU has, for several years, linked the continuation of GSP Plus to compliance with international conventions. This includes the condition that the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) be brought into line with international standards. The government’s alternative in the form of the draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PTSA) is less abusive on paper but is wider in scope and retains the core features of the PTA.

Governance and social justice factors cannot be ignored or downplayed in the pursuit of economic development. If Sri Lanka is to break out of its cycle of crisis and bailout, it must internalise the fact that good governance which promotes social justice and more fairly distributes the costs and fruits of development is the foundation on which durable economic growth is built. Without it, stabilisation will remain fragile, poverty will remain high, and the promise of 7 to 8 percent growth will remain elusive. The implementation of governance reforms will also have a positive effect through the creative mechanism of governance linked bonds, an innovation of the present IMF agreement.

The Sri Lankan think tank Verité Research played an important role in the development of governance linked bonds. They reduce the rate of interest payable by the government on outstanding debt on the basis that better governance leads to a reduction in risk for those who have lent their money to Sri Lanka. This is a direct financial reward for governance reform. The present IMF programme offers an opportunity not only to stabilise the economy but to strengthen the institutions that underpin it. That opportunity needs to be taken. Without it, the country cannot attract investment, expand exports and move towards shared prosperity and to a 7-8 percent growth rate that can lift the country out of its debt trap.

by Jehan Perera

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction