Features

The NPP’s proposed way out

by Uditha Devapriya

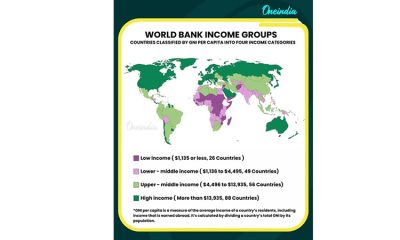

Promisingly titled “Rapid Response”, the NPP’s policy manifesto pits the party against the status quo and depicts itself as the clearly superior alternative. It advocates a politics free of corruption, a politics of the people. Written simply and striking an idealistic chord, it indicts every government since independence for the crisis we are in. This is to be expected with an outfit that views itself as better than the rest, and it is in line with the present mood, where people no longer care to distinguish between the regime and the opposition.

In such a scenario it is easy to claim, as the NPP does, that there’s no difference between the SLPP and the SJB. This explains Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s recent outbursts at Sajith Premadasa, the party’s rejection of the SLFP’s offer to get together, and its cold response to the prospect of an alliance with the Frontline Socialist Party. As far as sectarianism goes, the parliamentary avatar of the JVP is no different to the JVP.

The NPP is targeting something of a common denominator, what I have elsewhere called the golden mean of disgruntled voters. It reduces nearly everything to the corruption of the political class and comes close to condemning the idea of politics itself. That its policies are coloured by a jaundiced view of political representatives and that it considers other issues as peripheral can be gleaned from the opening lines of the manifesto: “We do not need a sophisticated grasp of statistics or politics,” it bluntly informs us, “to understand the socio-political catastrophe that has befallen our country.” In other words we don’t need to know: the facts speak for themselves and the writing is on the wall.

To indict all politicians apart from the NPP as equally responsible for the mess we are in is of course a convenient way out of figuring out what needs to be done to resolve that mess. It is for that reason, perhaps, that the NPP document does not offer substantive solutions, but veers with despairing frequency to vague suggestions and broad generalisations.

More pertinently, the authors of the manifesto draw a line between two kinds of people: those suffering and those responsible for the suffering. Laudable, but in trying to maintain that division everywhere, the NPP fails to come up with clear solutions; to give perhaps the best example, in its section on “Government Debt”, the authors admit to the severity of the crisis, but then offers to “develop a formal plan for the next five years.”

To be sure, the document is not without its merits. It is very clear about what it considers to the root of all our problems: the Open Economy. Whether or not you agree with its take, the NPP is specific on the point that it is the Open Economy that has entrenched corruption and greed, as well as the “unnecessary expansion of financialisation, austerity measures, subsidy cuts, market monopolies, inefficient borrowing, and sale of public property and state-owned enterprises.” To the best of my knowledge, the FSP is the only other party in the Opposition which traces the problems of our time to the post-1977 liberalisation of the economy. As far as its diagnosis goes, then, the NPP-JVP touts a distinctly socialist line.

Yet the NPP-JVP has evolved from what it used to be. Tactics and strategies are no longer what they once were. This, of course, has always been the JVP’s hallmark. As the late Hector Abhayavardhana used to say, it veered to the left of its leftwing opponents in the United Front government and to the right of its rightwing opponents in the Jayewardene regime. It opposed whoever was in power without formulating a clear programme that went beyond the goal of bringing down elected governments: this is why both its insurrections failed, and why the heroes of the first of them later turned to civil society outfits that are as opposed to political authoritarianism as they are to the JVP’s brand of “socialist” reform.

Today the JVP retains its critique of the Open Economy, but it has enmeshed it within an obscurantist anti-corruption discourse. That has made it eminently marketable to those who think the problems of the country are reducible to the excesses of its politicians, but at the exorbitant cost of ideological coherence. Indeed, the JVP’s shift from its supposedly Marxist roots to a parliamentary avatar housed by liberal and left-liberal intellectuals, activists, and artists, many of them allied with the yahapalana regime and not a few of them beneficiaries of yahapalanist largesse, points to a pivotal ideological turnaround.

The reforms these intellectuals urge are no different to those prescribed by the JVP’s liberal critics. They want to abolish the Executive Presidency and replace it with a parliamentary system. They want greater oversight over parliament. They want independent commissions and “completely independent” security services. They want asset declarations for MPs. They want more of what yahapalanist ideologues demanded, which was to reduce the powers of the government and transfer some of them to unelected professionals.

What is ironic here is that even MPs once allied with the spirit and letter of the yahapalanist project have swerved from these principles. Champika Ranawaka, for instance, no longer views the Executive Presidency as an evil to be abolished; replying to Victor Ivan, his proxies, including Anuruddha Pradeep Karnasuriya, now suggest that calls for abolition are based on exaggerated notions of the Presidency conceived by, of all people, Marxists.

Ranawaka has almost always been frank in his demonization of the Left, which is why these critiques should come as no surprise. What is surprising, however, is that those who batted for the overhaul of political systems, Ranawaka included, have turned the other way. The SJB is no different: it houses some of the most vociferous critics of the presidential system, but they are no longer as open about their criticism as they once were.

The point I am trying to make here is that the crisis we are undergoing today has swamped issues that we once thought mattered. Abolishing the presidency may have been the grand call of yahapalanist idealists, but now we have other things to worry about. What solutions do parties have vis-à-vis these issues? Do those solutions hold up? Are they clear or definite enough? Have they been conceived with the interests of the suffering many at heart? Can they be implemented, and if they can, how? If recent political turnarounds in Latin America and Central America are anything to go by, parties have a whole range of strategies open to them. Is the NPP availing itself of such strategies? Is it aware of them?

The NPP does not seem to be aware of them. Even if it is, it is not taking stock of them. Instead the NPP, and even the JVP, has caved into an abstract anti-political, anti-corruption discourse that has won it many fans, but not too many voters. Like its liberal critics, it has embraced a notion of politics free of politicians, a Radical Centrist view which reduces the problems we are facing to politicians and identifies the ruling class with their kind. It does offer criticisms of proposals like the privatisation of health and education, but then traces all these problems to the same source: the much derided 225 (MPs).

In aiming at a Centrist position, moreover, the NPP appears to be privileging compromises to hard-hitting reforms of the sort that progressive outfits in Latin America have opted for. This much is clear from a recent interview with the party leader: while highlighting the need for a better vision and reiterating they have that vision, Anura Kumara Dissanayake outlines a plan to “acquire at least USD 15 billion” by restructuring investment procedures. The NPP plans to do this, Dissanayake informs us, through “a long-term plan” that accounts for, inter alia, the “geographic setting”, “human resources”, and “civilisation” of the country. He does not specify what these are, where they can be found, and what should be done about them, but exudes a confidence in his party’s ability to make use of them.

In the final analysis, the NPP wants to bring together a broad coalition of anti-regimists. The clearer its policies are, the more specific its audience will be, and the more exclusivist it will appear to be. Hence, by limiting proposals like the implementation of import substitution to mere words, it can leave the task of specifying them to the future, no doubt after it wins an election. The NPP’s plan, in other words, is to keep as many as possible happy, targeting that golden mean of disgruntled voters I mentioned earlier.

Three decades of Third Way Centrism should make us realise that such tactics can only lead to electoral suicide. An obsession with reaching a compromise may win votes in the short term, but in the longer term it can only deprive parties of the radical potential they require to propose a way out. Why the NPP, of all parties, should opt for such a path, when recent developments in Latin America point to other strategies, boggles me.

Already influential think-tanks in the country are recalling and critiquing the JVP’s policies under the Chandrika Kumaratunga government. Already the middle-classes who professed admiration for the likes of Anura Kumara Dissanayake and Sunil Handunnetti are expressing disappointment with their proposals. What is the NPP’s response to them? We clearly need to know, but they are not giving us answers. This is to be regretted.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

From disaster relief to system change

The impact of Cyclone Ditwah was asymmetric. The rains and floods affected the central hills more severely than other parts of the country. The rebuilding process is now proceeding likewise in an asymmetric manner in which the Malaiyaha Tamil community is being disadvantaged. Disasters may be triggered by nature, but their effects are shaped by politics, history and long-standing exclusions. The Malaiyaha Tamils who live and work on plantations entered this crisis already disadvantaged. Cyclone Ditwah has exposed the central problem that has been with this community for generations.

A fundamental principle of justice and fair play is to recognise that those who are situated differently need to be treated differently. Equal treatment may yield inequitable outcomes to those who are unequal. This is not a radical idea. It is a core principle of good governance, reflected in constitutional guarantees of equality and in international standards on non-discrimination and social justice. The government itself made this point very powerfully when it provided a subsidy of Rs 200 a day to plantation workers out of the government budget to do justice to workers who had been unable to get the increase they demanded from plantation companies for nearly ten years. The same logic applies with even greater force in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah.

A discussion last week hosted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives on relief and rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah brought into sharp focus the major deprivation continually suffered by the Malaiyaha Tamils who are plantation workers. As descendants of indentured labourers brought from India by British colonial rulers over two centuries ago, plantation workers have been tied to plantations under dreadful conditions. Independence changed flags and constitutions, but it did not fundamentally change this relationship. The housing of plantation workers has not been significantly upgraded by either the government or plantation companies. Many families live in line rooms that were not designed for permanent habitation, let alone to withstand extreme weather events.

Unimplementable Promise

In the aftermath of the cyclone disaster, the government pledged to provide every family with relief measures, starting with Rs 25,000 to clean their houses and going up to Rs 5 million to rebuild them. Unfortunately, a large number of the affected Malaiyaha Tamil people have not received even the initial Rs 25,000. Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers do not own the land on which they live or the houses they occupy. As a result, they are not eligible to receive the relief offered by the government to which other victims of the cyclone disaster are entitled. This is where a historical injustice turns into a present-day policy failure. What is presented as non-partisan governance can end up reproducing discrimination.

The problem extends beyond housing. Equal rules applied to unequal conditions yield unequal outcomes. Plantation workers cannot register their small businesses because the land on which they conduct their businesses is owned by plantation companies. As their businesses are not registered, they are not eligible for government compensation for loss of business. In addition, government communication largely takes place in the Sinhala language. Many families have no clear idea of the processes to be followed, the documents required or the timelines involved. Information asymmetry deepens powerlessness. It is in this context that Malaiyaha Tamil politicians express their feeling that what is happening is racism. The fact is that a community that contributes enormously to the national economy remains excluded from the benefits of citizenship.

What makes this exclusion particularly unjust is that it is entirely unnecessary. There is anything between 200,000-240,000 hectares available to plantation companies. If each Malaiyaha Tamil family is given ten perches, this would amount to approximately one and a half million perches for an estimated one hundred and fifty thousand families. This works out to about four thousand hectares only, or roughly two percent of available plantation land. By way of contrast, Sinhala villages that need to be relocated are promised twenty perches per family. So far, the Malaiyaha Tamils have been promised nothing.

Adequate Land

At the CPA discussion, it was pointed out that there is adequate land on plantations that can be allocated to the Malaiyaha Tamil community. In the recent past, plantation land has been allocated for different economic purposes, including tourism, renewable energy and other commercial ventures. Official assessments presented to Parliament have acknowledged that substantial areas of plantation land remain underutilised or unproductive, particularly in the tea sector where ageing bushes, labour shortages and declining profitability have constrained effective land use. The argument that there is no land is therefore unconvincing. The real issue is not availability but political will and policy clarity.

Granting land rights to plantation communities needs also to be done in a systematic manner, with proper planning and consultation, and with care taken to ensure that the economic viability of the plantation economy is not undermined. There is also a need to explain to the larger Sri Lankan community the special circumstances under which the Malaiyaha Tamils became one of the country’s poorest communities. But these are matters of design, not excuses for inaction. The plantation sector has already adapted to major changes in ownership, labour patterns and land use. A carefully structured programme of land allocation for housing would strengthen rather than weaken long term stability.

Out of one million Malaiyaha Tamils, it is estimated that only 100,000 to 150,000 of them currently work on plantations. This alone should challenge outdated assumptions that land rights for plantation communities would undermine the plantation economy. What has not changed is the legal and social framework that keeps workers landless and dependent. The destruction of housing is now so great that plantation companies are unlikely to rebuild. They claim to be losing money. In the past, they have largely sought to extract value from estates rather than invest in long term community development. This leaves the government with a clear responsibility. Disaster recovery cannot be outsourced to entities that disclaim responsibility when it becomes inconvenient in dealing with citizens of the country with the vote.

The NPP government was elected on a promise of system change. The principle of equal treatment demands that Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers be vested with ownership of land for housing. Justice demands that this be done soon. In a context where many government programmes provide land to landless citizens across the country, providing land ownership to Malaiyaha Tamil families is good governance. Land ownership would allow plantation workers to register homes, businesses and cooperatives and would enable them to access credit, insurance and compensation which are rights of citizens guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, it would give them a stake that is not dependent on the goodwill of companies or the discretion of officials. The question now is whether the government will use this moment to rebuild houses and also a common citizenship that does not rupture again.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective

(This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.)

In 1977, addressing the Colombo Diocesan Council, Bishop Abeynaike made the following observation:

‘The World in which we live today is a sick and hungry world. Torture, terrorism, persecution seem to be accepted as part of our situation…We do not have to be very perceptive in Sri Lanka to see that the foundations of our national life are showing signs of disintegration…While some are concerned about these things, many more are mere observers…A kind of despair seeps into us like a dark mist. Who am I to carry any influence, anyway? (The Colombo Diocesan Council Address by the Rt Revd C L Abeynaike at the Diocesan Council 1977, ‘What the World Expects’ Ceylon Churchman (January/February 1978) 11.)

Nearly five decades later, it feels like not much has changed, in the world or in how we perceive our helplessness in relation to our public life. Many of us saw the crisis of 2022 in Sri Lanka as a crisis of political representation. We felt that our elected representatives were not only failing to act in our interests but were, quite boldly, abusing their office to serve their own interests. While that was certainly one reason for that crisis, it was not the only one. Along with each elected representative who may have abused their power, there were also a number of other public officials who either enabled it or failed to prevent that abuse of power. For whatever reasons, such public officials – whether in public administration, procurement or law and order – acted in ways which led to our loss of trust in public office. When we look further, we can also see that systems of education, religious institutions and cultural practices nurtured and enabled public officials to act in ways that caused this loss of public trust. We often doubt whether this system can be salvaged. However, speaking in 1977, Bishop Abeynaike reminds us that these are challenges that we ought to face collectively, and I quote again:

‘But the longest journey begins with the first step. In politics, as in religion, faith without works is dead. We are caught up with unifying faces that create proximity and with divisive faces that disrupt community. We have to discover how to build community in proximity.’ (The Colombo Diocesan Council Address by the Rt Revd C L Abeynaike at the Diocesan Council 1977, ‘What the World Expects’ Ceylon Churchman (January/February 1978) 11-12)

In my view, that task of building ‘community in proximity’ includes reviving and strengthening our public discourse about public office that focuses on securing public trust. This is why I proposed to provide a Christian perspective on Securing Public Trust in Public Office for this year’s Abeynaike memorial lecture. In the next 50 minutes, I will suggest to you that public officials ought to nurture and cultivate five attributes: truthfulness, rationality, conviction, critical introspection and compassion. To illustrate the scope of these five attributes, I have chosen four examples. Let me present them to you now and as I present the five attributes, I will selectively refer back to these examples.

Example 01 : In 2002, in Kandy, a group of persons threw acid at Audit Superintendent Lalith Ambanwela. The reason for this attack was Ambanwela’s disclosure of a fraud of Rs 17.5 million in purchasing computers for the Central Province Dept. of Education in 2002 (Daily Mirror 25 May 2021). This acid attack caused Ambanwela grave and life-threatening harm. Unusual for cases of this nature, the accused were tried and convicted by the Kandy High Court. Referring to this judgement, Ambanwela said, and I quote, ‘This is a good judgment given on behalf of the future of the country. This is not my personal victory. It is a victory gained by government servants on behalf of good governance’(Judgement promoting good governance, TISL, 25 October, 2012). In 2004, the Sri Lanka chapter of Transparency International awarded Mr Ambanwela the National Integrity Award.

Example 02 : In 2014, South Africa’s Public Protector, Thuli Madonsela, published a report titled ‘Secure in Comfort’ (Report No 25 of 23/24, March 19, 2014). This was a report that concluded that the then President of South Africa had, among other things, enriched himself and his family by excessive spending to improve his private family home – purportedly to improve security. The President rejected the report and refused to comply with the decision that the misused public funds should be paid back. Over the next two years this battle for accountability continued. As Thuli Madonsela ended her term in October 2016, she finalised and fought to release another report, titled ‘State of Capture’ (Report No: 6 of 206/17). This report documented entrenched corruption involving a leading business family and President Zuma in which the public protector recommended a judicial inquiry commission. By early 2018, President Zuma resigned under threat of facing a no-confidence motion in Parliament, primarily over these two matters.

Example 03 : William Wilberforce was a British politician who lived in 18th century England. He was a member of the British Parliament, a leading figure in the Anit-Slavery movement of that time and, relevant for this lecture, a Christian. His first unsuccessful attempt at proposing the adoption of a law to prohibit the slave trade was in 1789. Since then, he failed 11 times in trying to bring about this law and eventually, 15 years later, he succeeded on the 12th occasion, in 1807. He then went on to push for the abolition of slavery itself but retired from politics in 1825. In 1833, 44 years since he began his anti-slavery work in Parliament and three days before his death, slavery was abolished in the United Kingdom (Slavery Abolition Act 1833).

Example 04 : In April 2022, Sri Lanka declared its first ever default from sovereign debt repayment. This default was a result of a worsening balance of trade over decades and due to a series of political and expert decisions that led Sri Lanka into a debt. As we all know, this was a time when the people mobilised peacefully, reacting to the systematic institutional failures and demanding a ‘system change’, particularly, but not limited to, a change in a system of governance headed by an Executive President. Much has been said about the events of 2022, but for the purposes of today’s talk, I would like to recall the several failures on the part of public officials, including of our elected representatives, that led us to this crisis point. People died, while waiting in queue, to pay and obtain fuel or gas. Such was the extent of that tragedy. Today, much of the cost of the mismanagement, negligence, abuse of power and recovery are borne by you and me, including for example the losses incurred by SriLankan Airlines.

Before I use these examples to present the five attributes of public office, permit me to explain what I mean by public office, the idea of securing public trust and describe what I understand to be a Christian perspective on both.

Public Office

We often associate elected representatives, or public servants, with the term public office. But I will use this term in a broader sense today. For the purposes of today’s talk, I include within the idea any office that requires the person holding that office to exercise power or authority under public law. This description would cover members of Parliament, the President, members of the Judiciary, the police and public servants. In the Sri Lankan context, it would also include university academics and members of what we commonly describe as independent commissions such as the Human Rights Commission and the Election Commission.

When we consider all these personnel at this general level, we must bear in mind that different limitations and protections apply to different types of public officials. For instance, the role of judges is unique and comes with extensive limitations and protections in contrast with the role of an elected representative. Members of the judiciary are diligently required to avoid not only actual conflicts of interests but also perceived conflicts of interest and, therefore, are often very selective in their public engagements unlike legislators. University academics enjoy academic freedom, a freedom not available to public servants. Doctors in the public health system enjoy professional discretion while members of the police are subject to a unique form of order and discipline. Broadly speaking, different types of public officials play a unique and essential role in sustaining our collective life which is why public trust on public officials assumes great significance.

Public Trust

Public trust is a concept that I have worked with for about 15 years in relation to public law in Sri Lanka. (The basic idea here is that anyone who exercises public power ought to exercise that power only for the benefit of the People. The ‘Public Trust Doctrine’ is a public law concept that seeks to enforce this idea in the law. In several jurisdictions in the world, the Public Trust Doctrine has been invoked by judges to recognise rights of the natural environment or rights to the natural environment and a corresponding duty on the state to respect such rights. In Sri Lanka, however, the public trust doctrine has been developed much more broadly by judges to review the exercise of executive discretion and to decide whether such discretion has been exercised for the benefit of the people or not. Examples of executive discretion would include the discretion that lies with the Executive President to grant a pardon to a convict, the discretion that lies with the Governor and Monetary Board of Sri Lanka to determine Sri Lanka’s monetary policy and the discretion that lies with the Cabinet of Ministers to manage state assets. Over the last three decades, Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court has developed the public trust doctrine to recognise that the exercise of public power must be reasonable, that it cannot be arbitrary and that it must only be for the benefit of the people. I draw from this idea of the public trust doctrine to ask a more ethical question as to what can be done to secure public trust, by public officials.

A Christian Perspective

How do we identify a Christian perspective on securing public trust? There are at least two approaches: one is the evangelical approach where we draw from the life of Jesus, and the second is the broader Anglican approach which combines the first, with the teachings of the Church as well. Of course, Christ did not exercise public power nor did he hold public office. But through his ministry and the Bible more generally, we learn about the Kingdom of God – its purpose and its value commitments. The calling for Christians is to internalise and practice the values of the Kingdom of God in all we do, including in our public lives and to offer that perspective to the rest of the world. For this talk, therefore, I derive my Christian perspective from the Bible, the teachings of the Church and through that from our collective understanding of the Kingdom of God. It is important to bear in mind that much of what we draw from our faith may resonate with the other faiths that are practiced in Sri Lankan society or may be explained in secular terms too.

I now turn to the main task I have set up for myself today – which is to try to interpret what a Christian perspective may have to offer in securing public trust in public office. I present my ideas through five attributes: 1) truthfulness, 2) rationality, 3) conviction 4) critical introspection and 5) compassion. I chose these attributes drawing on my study of the deficit of public trust in our public officials here in Sri Lanka but also from my own experiences.

· Truthfulness

Of the five attributes that I present to you today, truthfulness might be the one that is most familiar to us. Truthfulness is a common demand placed on us by most religions and can have an internal and an external dimension.

What do the scriptures have to offer us in this regard? Consider the example of Jesus in relation to the adulterous woman in the Gospel of John 8: 1-9. In that account, Jesus had significant power to influence how the religious establishment and the broader public would react to her and indeed, determine how she should be punished for being adulterous. In that moment, rather than exercise a harsh power of judgement, Jesus intentionally chose to take the path of truthfulness. The truthfulness that he exercised there had an internal or personal dimension as well as an external and structural dimension to it. At the internal or personal level, through his act, he demanded that those who sought to punish this woman, be truthful about their own conduct. But in doing so, he truthfully drew attention to the religious and cultural structures of that society which sought to selectively penalise and condemn women. The woman did not get a free pass either. Jesus asked her too, to be truthful and leave her life of sin.

A helpful contemporary challenge that we can apply these principles to would be the responsibilities of public officials to be truthful about practices such as corruption, ragging or sexual harassment internal to our public institutions. What does it mean, for a public official, to be truthful in the face of these deeply problematic and entrenched injustices within our public institutions and in the way in which these public institutions offer their services to society? In the context of holding public office, being truthful about these issues is often inconvenient, uncomfortable and has too many implications for the status quo. Being truthful often requires too much work. It causes persons who hold public office to become unpopular, disliked, be made of targets for retaliation and in some instances to even have to risk losing their jobs. It is useful to recall here that speaking the truth about himself, that is his claim to be the Messiah, led Jesus ultimately to his crucifixion.

Speaking truth to power is equally difficult and often can attract serious risks. In his brief public life of three years, Jesus did not hold back from speaking truth to power. One of my personal favourites is his description of the Pharisees as graves painted in white (Matthew 23:27). For public officers, speaking truth to power may entail calling out the abuse of power, refusing to engage in or endorse illegal actions and being willing to take action against wrongdoing.

Recall here my first example of the acid attack against Lalith Ambanwela. He nearly paid for his truthfulness with his life, is reported to have lost sight in one eye and his face was permanently disfigured. Why then, should public officials be truthful and in what ways would it help to secure public trust? From a Christian perspective, there are two ways to justify the attribute of truthfulness. First, it is an attribute that we practice for its intrinsic value. As Christians, we believe that the God of the Bible is true and practices truthfulness and requires the same of those who follow him. Followers of Christ are required to be lovers and seekers of the truth. The second reason is consequentialist. The Christian perspective requires that we are truthful because the absence of truth is a lie, an injustice and God abhors the lie as well as injustice. (To be continued)

By Dinesha Samararatne

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

Features

Making waves … in the Seychelles

The group Mirage, led by drummer and vocalist Donald Pieries, just returned from a little over a month-long engagement in the Seychelles, and reports indicate that it was a happening scene at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort.

The group Mirage, led by drummer and vocalist Donald Pieries, just returned from a little over a month-long engagement in the Seychelles, and reports indicate that it was a happening scene at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort.

The band even adjusted their repertoire to include local and African songs, and New Year’s Eve turned out to be a memorable event for the guests who turned up to usher in 2026.

The scene became active, around 8.00 pm, and the lead up to the dawning of the New Year was nostalgic as the crowd was on the floor, enjoying the music of Mirage.

As the New Year approached, the countdown began and then it was ‘Auld Lang Syne,’with everyone participating in the singing.

Enjoying the 31st night scene … on the dance floor

Mirage did six nights a week at the Lo Brizan and it was their fourth trip to the Seychelles, and they go back again this year – in April, August, and for the festive season in December.

Guests patronising this outlet, include French, German and Russian tourists, and locals, as well, and the group’s repertoire is made up of songs that include Russian, French and German, and the language spoken in the Seychelles, Creole, with female vocalist Danu being quite adaptive, singing in all four languages.

Many attribute the band’s success to Donald Pieries, including their recent engagement in the Seychelles.

Interestingly, Donald’s been with Mirage through various lineup changes, and he’s currently fronting an extremely talented lineup, made up of Sudham (bass/vocals), Gayan (lead guitar/vocals), Danu (female vocalist) and Toosha (keyboards).

Donald is also quite the family man – his 50th wedding anniversary was recently celebrated in style in the Seychelles.

In Colombo, Mirage will be obliging music lovers every Friday at the Irish Pub.

In fact, they went into action at the Food Harbour, Port City, Colombo, on the 23rd and 24th of this month.

Mirage: Extremely popular with the crowd at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor