Opinion

The most dangerous moment

By Jayantha Somasundaram

“British Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered the most dangerous moment of the Second World War, and the one which caused him the greatest alarm, was when news was received that the Japanese Fleet was heading for Ceylon.” –The Most Dangerous Moment by Michael Tomlinson (1976) William Kimber, London.

It is 80 years since Ceylon, the British colony, came under attack from a Japanese armada on Easter Sunday 5th April 1942. The Second World War, which commenced in September 1939, was a distant war, with the theatre of war being initially Europe and North Africa. Commencing with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the defeat of British forces in Malaya, in January 1942, and the fall of Singapore in February, World War II entered the Indian Ocean, and its epicentre British Ceylon.

In British strategic perception, Fortress Singapore was the key to the protection of their colonies on the Indian Ocean littoral and the sea route to East Asia. With the fall of Singapore, the Indian Ocean became the central theatre of the War. In the Indian Ocean itself the fulcrum of maritime control rested in Ceylon and the Maldives. And this perception predated the Japanese entry into the War in December 1941.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had written to the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand in August 1940, that in the event of Japan entering the War “we should also be able to base on Ceylon a battle cruiser and a fast aircraft carrier which, with Australian and New Zealand cruisers and destroyers… act as a very powerful deterrent.”

If the Japanese took Ceylon, the Maldives, the Seychelles and Christmas Island they could paralyse Allied shipping and resupply to its theatres globally, in Europe and in Asia. This included US shipments to the Soviet Union, via the Persian Gulf, and to China, via the Bay of Bengal. The Japanese could even ultimately link hands with the Germans, now advancing towards Cairo and Suez, in North Africa.

Vice-Admiral James Somerville, Commander of the Royal Navy’s (RN) Eastern Fleet, would later explain to Australia’s Minister of External Affairs, Dr Herbert Evatt, why he was not stationed in Western Australia, because “Ceylon flanks, or covers, all vital lines of communication to the Middle East, India and Australia,” while Australia, lying as it does at the end of a line of communication, was not the ideal location for protecting the Allied sea lanes across the Indian Ocean.

Ceylon’s Loyalty

At the outbreak of the War, Governor Andrew Caldecott wrote to the Colonial Office that the Ceylon National Congress dominated State Council had passed a resolution pledging loyalty to London, unlike the rebellious Indian National Congress in the more important British colony India. In June 1940 Caldecott went on to report to the Colonial Office that the only exception was the “left-wing Samajists (sic) … (who) have come out definitely anti-British.” And in September 1940 Caldecott went further telling the Colonial Office that “Ceylon’s loyalty to the Empire during the War which I assess at over 99 per cent…is due to…a high sentimental regard for the King’s Person and Throne.”

When Singapore fell on 15 February the Chiefs of Staff, ̶̶ the heads of the RN, the British Army and the Royal Air Force (RAF) ̶̶ asserted that “the basis of our general strategy lies in the safety of our sea communications for which secure naval and air bases are essential…Thus we must secure Ceylon…The loss of Ceylon will imperil our whole British War effort in the Middle East and Far East.”

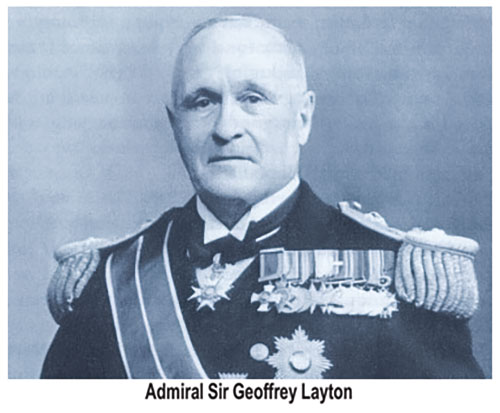

Meanwhile, on 26th February, Churchill suggested to the Commander-in-Chief India, General Archibald Wavell, who was on his way to Ceylon, to consider a Supreme Commander in overall charge of the Island in order to prevent a repetition of Singapore. On 5th March Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton was promoted Commander-in-Chief Ceylon, “London took the drastic step of subordinating the Island’s civil authorities to military command.” This was “Britain’s first experiment with unified command in an operational theatre.”

Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton

However, not only was Britain’s airpower in the Indian Ocean weak, they lacked an adequate maritime capability that could halt the advance of the expected Japanese carrier fleet. In fact Admiral Layton complained that “he was profoundly shocked … that Ceylon was virtually defenceless.”

In response “at the highest levels of war direction, Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff determined that Ceylon could not be allowed to fall and pumped in troops and aircraft while strengthening the Island’s shore defences and base infrastructure,” wrote Ashley Jackson in his 2018 book Ceylon at War 1939-1945. “The British Government was pulling out all the stops to reinforce the Indian Ocean and get troops and aircraft to Ceylon, but things took time to move across vast distances. It was a race against time.”

The Eastern Fleet

The First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound decided to withdraw the battleship HMS Warspite and the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable which were under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville from the Eastern Mediterranean and move them to Ceylon where Somerville would assume command of the Eastern Fleet. They were followed by four Revenge-class battleships and six destroyers.

By end March the Eastern Fleet included one light and two fleet carriers, five battleships, seven cruisers, 16 destroyers and seven submarines. The Eastern Fleet maintained seven shore bases including in India, the Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles. Further, the RN’s East Indies Station was relocated to Colombo, with headquarters now at shore base HMS Lanka.

On 14th March, Admiral Layton ordered the evacuation from Ceylon of all non-residents, servicemen’s wives, European women and children; all except those doing essential work. While London rushed weapons, equipment and personnel to Ceylon, Admiral Layton strengthened the institutions and military capability of the Island’s defences.

Admiral Geoffrey Layton operated from the ‘Old’ Secretariat at Galle Face. Under his command were Admiral Somerville, Commander of the Eastern Fleet, Admiral Geoffrey Arbuthnot, Commander East Indies Station, General Officer Commanding Troops Major General Roland Inskip and Air Vice-Marshal John D’Albiac as Air Officer Commanding No. 222 Group. Capt Palliser RN was appointed Trincomalee Fortress Commander.

Troop reinforcements arriving in Ceylon included the 65th Heavy Anti Aircraft Regiment, 43rd Light Anti Aircraft Regiment and RAF personnel. 62 heavy and 100 light anti-aircraft guns along with barrage balloons, searchlights and radar units were established. This prompted the requisition of S. Thomas’ College Mount Lavinia for the accommodation of officers and St. Joseph’s College Maradana, for that of the men. “Schools and public buildings, hotels and houses were requisitioned to accommodate the new forces pouring into the island along with all that was needed to support them,” records Jackson.

Admiral Layton conceived, inspired and drove the hurried preparations, dictating to and overriding the key actors. Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the King’s cousin observed that even “the Governor is definitely under the Commander-in-Chief.”

Layton’s language and manner were rough quarter deck style. At the War Council meeting when a future Prime Minster John Kotelawala Minister of Communications and Works, responded to a query from Layton regarding a task with “the head overseer is having a lot of trouble with supplies;” Layton barked “then give him six on the backside!”

And when a future Governor-General, Civil Defence Commissioner Oliver Goonetilleke protested to Governor Andrew Caldecott that Layton had called him a black bastard, the Governor replied, “My dear fellow that is nothing to what he calls me!” Admiral Somerville explained to First Sea Lord Pound that “Layton takes complete charge of Ceylon and stands no nonsense from anyone.”

Battle for Ceylon

Meanwhile the Ratmalana Civil aerodrome was commandeered by the RAF and its runway doubled in length, the Colombo Museum became Army HQ, a flying boat base was developed at Koggala, fighter airbases opened in Dambulla, Minneriya and Vavuniya and a fleet air arm airbase at Katukurunda. Ashley Jackson, Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College London, in his 2009 paper War on the Home Front in Ceylon, writes “Ceylon was transformed from a (military) backwater into a key Allied military base.”

Number 258 Fighter Squadron withdrawn from Malaya and after seeing action in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) was re-equipped with Hurricanes from Karachi RAF Depot and reformed at Ratmalana on 30th March. It was then transferred to the new Colombo Racecourse RAF Base at Reid Avenue, with provision for the aircrew to sleep in the Grandstand during alerts and emergencies. Under Squadron Leader Peter Fletcher from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) its pilots were from America, Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The RAF’s Fighter Operations Room was located at Bishop’s College, Kollupitiya.

The Battle for Ceylon was going to be a duel of skill, nerves and grit between the pilots of the approaching Japanese Carrier Fleet and the RAF fighter pilots defending Ceylon. The Air Order of Battle in Ceylon was:

Number 11 Bomber (Blenheim) Squadron at the Race Course, 30 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at Ratmalana, 205 Maritime Reconnaissance (Catalina) Sq at Koggala, 258 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at the Race Course, 261 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at China Bay, 273 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq at China Bay, 788 Torpedo Bomber (Swordfish) Sq at China Bay, 803 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq Ratmalana and 806 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq Ratmalana.

Carrier borne aircraft on HMS Indomitable: 11 Sea Hurricanes, 10 Fulmar, 24 Albacore and 2 Swordfish.

On HMS Formidable: 21 Albacores and 12 Martlets

On HMS Hermes: 12 Swordfish.

The Eastern Fleet had 29 major warships, and they were divided into the Fast Division known as Force A and the Slow Division Force B. On 30th March well aware that the Japanese Fleet was in the Indian Ocean and heading for Ceylon, Admiral Somerville put to sea in the hope of intercepting the enemy fleet south of the Island. Somerville reasoned that Ceylon faced a night attack by Japanese aircraft, probably when the moon would be full on 01 April. But after two days of fruitless search the Eastern Fleet changed course on 3rd April and headed for Addu Atoll in the Maldives in order to replenish their stock of fuel and water.

(To be continued)

Opinion

M. D. Banda: Memories of our Appachchi

(The 112th Birth Anniversary M. D. Banda fell on March 09.)

My memories of Appachchi when I was very little are nebulous. Whilst this may be the case with all little children, even ones with fathers who have regular 9-5 jobs, in my case, this was due to two additional reasons: our Appachchi lived mostly at “Shravasthi” the special residence for Lankan parliamentarians and not at our ancestral home home, in our village, Panaliya.

Additionally, we were all at boarding schools and spent nine months of the year in our respective school hostels. Thus, it was just during the holidays that the seven of us (my four sisters, two brothers and I) were at home, in Panaliya.

Looking back on this time, I realise that during most of my childhood my father was a Cabinet Minister, and one who was completely dedicated to his duties. He was conscientious to a fault, attending to ministerial duties, attending parliamentary sittings and cabinet meetings diligently. Appachchi first entered Parliament in 1947 when he was just 29 years old, and

was almost immediately appointed to the post of Parliamentary Secretary (Junior Minister) to the Minister of Labour and Social Services in May 1948. He was Minister of Labour and Social Services in February in 1950 and was again appointed to the same post by Hon Dudley Senanayake in March 1952. He became Minister of Education in June 1952 so that by the time I was born in December 1952, he was a senior member of the Dudley Senanayake Cabinet. I only fully realised how busy he must have been much later in life. As young children, it is our mother who gave us love and a sense of security by being fully present in our lives and seeing to all our needs, even when we were in school hostels.

Pivotal points

Our mother informed us one day, when I was around 3 or 4 years old , that Appachchi would be coming home that evening. Although my memories of this period are quite hazy, I recall very clearly the keen enthusiasm with which we awaited his arrival. Evening moved into night and his arrival was pushed back late and further late into the night. The moment I woke up the next morning I remember asking Amma where Appachchi was. “He came home very late last night but had to leave early this morning. He was a little annoyed with you, Lokka (everyone in the family calls me ‘Lokka’ even now), because you had parked your little car near the stairway, and Appachchi nearly tripped over it’ (this was before we had electricity in our home). My little heart was overwhelmed with sorrow for not only had I not seen Appachchi but I had inadvertently caused him injury with my careless parking of my miniature car.

This incident is indelibly etched in my mind because I believe that this was the first time in my life, that I experienced the agony of shattered expectations. Why I felt such intense pain then as a little child was perhaps because of how much I loved my father.

I was admitted to Hillwood College, Kandy at the age of three and a half and lived in the school hostel for three years. I clearly remember Amma visiting us at least once or twice a month with goodies and treats for us and our friends. I do not however have any clear memory of Appachchi visiting us during this time. At the time I didn’t realise that this was due to the busy life he led. At Hillwood, I had all the love and attention I needed from my four older sisters and my four older cousin sisters (our Lokuamma’s daughters).

My younger brother Senaka and I then entered Dharmaraja College, Kandy in 1961 . We were hostelers and attended school from the hostel. I clearly remember Amma visiting us regularly during this period too. I had my first real and meaningful conversation with Appachchi during this time: One day, our warden Mr Wimalachandra informed me that appachchi had come to take Senaka mallie and me out. We visited a relative of ours in Harispattuwa, had lunch with them and on our return journey to the school hostel, I told appachchi that I was playing cricket for the under 12 team at Dharmaraja College, and therefore needed a bat.

“Are you playing hardball?”

(I didn’t understand the question so I was silent)

“Is it the red ball?”

“Ah, yes.”

“Is it that kind of bat that you need?”

“Yes.”

“What is your position in the team?”

(I was once again silent)

“Are you an opening batsman? Or are you number 3, 4 or 5?”

“I can bat and bowl. I do both”

“Ah! Then you are an all-rounder. Number 6,7 – I will buy you this kind of bat. Play well till then.”

And the conversation continued in the vein but no bat has come to date!!!

Little did I know at the time that Appachchi was himself an outstanding cricketer, who represented the St Anthony’s College.Katugastota team and, later, for the Ceylon University College team, as an opening batsman. This is why he was so well versed with the game and was highly interested in my own cricketing capabilities. His passion for cricket was clear to us later on too because we all recall how he and his nephews, Bertie and Nimal, would listen to cricket commentaries and were glued to the radio when England and Australia played biennially for the famous Ashes trophy.

On the day of this momentous conversation, Bertie aiya (appachchi’s long-time Private Secretary, and his sister’s son; a lawyer by profession) had also come with Appachchi. It is from Bertie aiya that I learnt that day that the car they had driven up to Kandy in (an Austin A 70) belonged to Appachchi. I later learnt that Appachchi had not one but two cars (a Fiat 1400 too). Both cars were driven by Ranbanda, the chauffer, and were in Colombo because there was no one who could drive them at Panaliya. Amma always hired a car for her personal use at Panaliya, and would visit us in school in these hired cars, until her youngest brother Tissa came to live in our home at Panaliya. Tissa maama then drove amma around and would very often drive us to our school hostels. Another rather amusing memory from this same time goes like this: during a school holiday when I was in grade 6 at Dharmaraja College, Appachchi asked for my report card. I was 6 th

in class and therefore promptly and proudly took it to him. Appachchi scrutinised my report card carefully and said, not unkindly, ‘If you are 6 th in class with marks like this, all the other children in your class must be buffaloes’.

A shift in gears

I think I really got to know Appachchi well when Senaka malli and I entered Ananda College in Colombo. Although we first went to school from the school hostel, we would go to Appachchi’s official residence at Wijerama Mawatha every weekend. By this time, Amma too had moved to Colombo. Thus, between 1965 – 1970 , our home was at Wijerama Mawatha, with them. So, that is when I got the chance to interact closely with Appachchi. It was only at this time that it dawned on me that Appachchi was a powerful Cabinet Minister who was loved and respected by his constituents and the people of our country.

During this time, when I needed anything, I would go to his room early in the morning to remind him of what I needed. These requests were for the most part fulfilled.

Once I remember that I asked for track shoes (spikes) and Appachchi bought me a pair from abroad. When I needed money to buy a Tennis racket, he told me to go to the sports-ware store, ‘Chands’ at Chatham Street and select a racket. I received top treatment there and was even offered orange barley!

Then again I urgently needed ‘longs’ (trousers) to wear to school. “How many do you need?” he asked. Without thinking I said, “six”. “Why six?” he demanded. “There are only 5 days in the school week, no? Three would do.” Then he directed me to the ‘West End’ tailors’ shop in Pettah and asked me to get them stitched there.

It was Appachchi’s habit to take us to the Lake House Book shop every year and allow us to buy whatever we wanted. Considering that there were 7 of us, Senaka Malli and I chose just three or four books and took them to the counter, while our Chuti Malli Senerath, would bring a pile of books! “Do you want all these books?” Appachchi asked. Chuti Malli nodded “yes” and Appachchi bought all of them for him! This was probably because Appachchi himself loved books and wished to encourage the reading habit in his children.

When apachchi passed away in 1974, Senerath Malli was only 14 years old and I believe that the loss was greatest for him.

(To be concluded)

Loku Putha,

Gamini Leeniyagolla

Opinion

Social and Biological Landscape of Kidney Disease in Sri Lanka

World Kidney Day falls today

The Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) crisis in Sri Lanka represents one of the most formidable public health challenges of the twenty-first century, manifesting as a complex tapestry of environmental, social, and physiological factors. Unlike the traditional forms of kidney disease seen in urban centres—which typically stem from well-understood comorbidities like long-term diabetes and hypertension—the situation in the Sri Lankan ‘Dry Zone’ is defined by a mysterious and aggressive variant known as Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu). This specific form of the disease has devastated the agricultural heartlands, particularly the North Central Province, for over three decades, yet it continues to evolve in its geographic reach and its socio-economic impact as of 2026. The persistence of this epidemic despite extensive international research highlights a profound gap in our understanding of how tropical environments and traditional occupational hazards intersect to damage human renal systems.

Historically, the emergence of CKDu was first noted in the late 1990s around the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa districts. What began as sporadic cases in rural hospitals quickly transformed into a localized epidemic, catching the medical community off guard because the patients did not present with the usual risk factors. These were not the sedentary, elderly populations usually associated with renal failure; rather, they were lean, active, middle-aged rice farmers.

The demographic specificity of the disease remains a chilling hallmark of the crisis today. It predominantly strikes men during their peak productive years, which triggers a catastrophic ripple effect through the family unit. When a primary breadwinner in a subsistence farming household falls ill, the family is thrust into a ‘poverty trap’ where limited resources are redirected toward transport to distant clinics, expensive nutritional supplements, and eventually, the gruelling routine of dialysis. This economic erosion often forces children out of school and into labour, perpetuating a cycle of systemic vulnerability that lasts for generations.

Intense scientific debate

The aetiology of the disease remains a subject of intense scientific debate and is currently viewed through a multifactorial lens. Researchers have moved away from the search for a single ‘smoking gun’ and are instead examining a lethal synergy of environmental triggers. Groundwater quality remains at the forefront of this investigation. The dry zone of Sri Lanka is characterized by high levels of fluoride and groundwater hardness, and it is theorized that the interaction between these natural minerals and anthropogenic pollutants—such as heavy metals from agrochemicals—creates a nephrotoxic cocktail.

The historical reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides in the ‘Green Revolution’ era of Sri Lankan agriculture is often cited as a major contributing factor. While direct links to specific brands of pesticides have been difficult to prove definitively, the accumulation of cadmium, arsenic, and lead in the soil and food chain continues to be monitored as a primary catalyst for the slow, progressive scarring of the kidney tubules.

In recent years, the discourse around CKDu has expanded to include the role of heat stress and chronic dehydration, exacerbated by the changing climate. Farmers in the North Central and Eastern provinces work long hours under an unforgiving sun, often without access to adequate quantities of clean drinking water.

There is growing evidence that repeated episodes of acute kidney injury caused by dehydration can lead to the permanent interstitial fibrosis characteristic of CKDu. This theory connects the Sri Lankan experience with similar ‘Mesoamerican Nephropathy’ seen among sugarcane workers in Central America, suggesting that CKDu may be a global phenomenon tied to the physical realities of manual labour in warming tropical climates. As global temperatures rise, the ‘heat stress’ hypothesis gains more urgency, positioning the Sri Lankan crisis not just as a local medical mystery, but as an early warning sign of how climate change impacts the health of the global agrarian workforce.

Geographical expansion of disease

The geographic expansion of the disease is a significant concern for the Ministry of Health in 2026. While Anuradhapura remains the epicentre, new ‘hotspots’ have been identified in the Uva and Northwestern provinces, as well as parts of the Southern hinterlands. This spread suggests that the environmental or behavioural triggers are more widespread than previously thought or that the migration of labour and changing agricultural practices are carrying the risk factors into new territories. The government has responded by shifting its strategy toward a more decentralized model of care. The establishment of the Specialized Nephrology Hospital in Polonnaruwa was a landmark achievement, providing state-of-the-art facilities for transplantation and dialysis. However, the sheer volume of patients means that the burden on tertiary care centres remains unsustainable. Consequently, the focus has shifted toward early detection through mobile screening units and the empowerment of primary healthcare centres to manage the early stages of the disease through aggressive blood pressure control and dietary management.

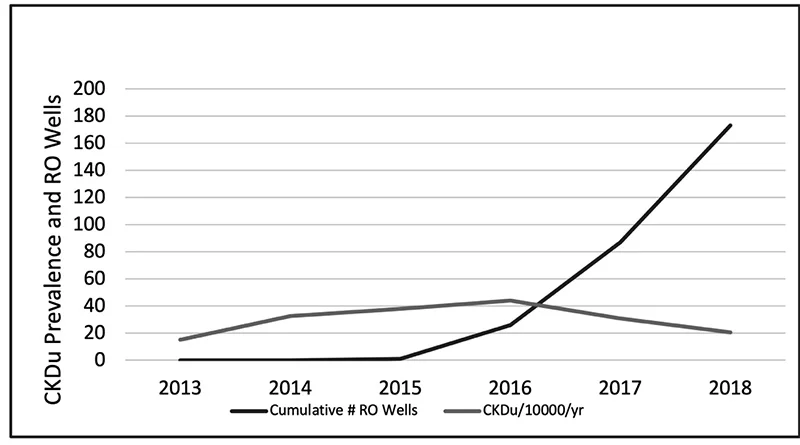

Water Security

Water security has become the primary defensive strategy in the national fight against CKDu. The widespread installation of Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants across high-risk villages has been a transformative community-led intervention. These plants provide filtered water that is significantly lower in mineral content and potential toxins compared to traditional shallow wells. While the long-term efficacy of RO water in preventing new cases is still being evaluated through longitudinal studies, there is strong anecdotal and preliminary evidence suggesting a decline in the rate of new diagnoses in villages that have had consistent access to filtered water for over a decade.

However, the maintenance of these plants remains a challenge, as rural communities often lack the technical expertise or the consistent funding required to replace membranes and ensure the water remains safe for consumption over the long term.

Beyond the biological and environmental dimensions, the CKD situation in Sri Lanka is deeply tied to the social fabric and the psychological well-being of the rural population. There is a profound stigma attached to the disease; in some areas, families hide a diagnosis for fear that it will affect the marriage prospects of their children or lead to social isolation.

This fear often drives patients toward traditional healers or unregulated ‘cures,’ which can sometimes exacerbate kidney damage through the use of heavy-metal-rich herbal preparations. Addressing the ‘fear factor’ through community education and the normalization of regular screening is as essential as any medical treatment. Furthermore, the mental health of caregivers—often women who must balance farming, household duties, and the intensive care of a bedridden relative—is a neglected aspect of the crisis that requires urgent policy attention.

Need for paradigm shift

As we look toward the future, the resolution of the CKD crisis in Sri Lanka will require a paradigm shift in how the state manages its agricultural and environmental resources. The transition toward organic or ‘low input’ farming is being discussed not just as an ecological goal, but as a public health necessity to reduce the chemical load on the soil and water. Simultaneously, the push for universal access to pipe-borne water is the only permanent solution to the groundwater problem. The current situation in 2026 is one of cautious optimism tempered by the reality of a massive existing patient load. While the ‘mystery’ of CKDu may never be reduced to a single cause, the integrated approach of clean water, early detection, and social support offers a roadmap for mitigating the impact of this devastating epidemic.

The resilience of the Sri Lankan farming communities, supported by robust scientific research and empathetic governance, remains the greatest asset in overcoming a disease that has for too long defined the landscape of the Dry Zone.

The Northwestern Province of Sri Lanka, particularly within the districts of Kurunegala and Puttalam, has emerged as a critical front in the national battle against chronic kidney disease. Unlike the early epicentre in the North Central Province, the Northwestern region faced a delayed but rapid surge in cases, largely attributed to its unique hydro-geochemical profile.

The groundwater in areas such as Polpithigama and Nikaweratiya is characterized by high levels of calcium and magnesium, leading to extreme water hardness that, when coupled with fluoride, has been statistically linked to accelerated renal damage. As of 2026, the strategy for this province has shifted from reactive medical treatment to a massive expansion of safe drinking water infrastructure, reflecting a policy acknowledgment that the quality of the ‘input’ into the human body is the single most controllable variable in the CKD epidemic.

Clean water projects

Central to this effort is the National Water Supply and Drainage Board’s Regional Support Centre for the North-Western Province, which has accelerated its goal of achieving near-universal pipe-borne water coverage. A primary focus has been the Anamaduwa Integrated Water Supply Project, a multi-billion-rupee initiative designed to serve over 80,000 residents across the most vulnerable divisions. By transitioning communities away from shallow, untreated agricultural wells and toward centralized, treated surface water systems, the project aims to bypass the nephrotoxic minerals inherent in the local bedrock. This shift is not merely a matter of convenience; it is a life-saving intervention. Early longitudinal data from 2024 and 2025 suggests that in villages where pipe-borne water has replaced groundwater as the primary source for over five years, the rate of new Stage 1 CKDu diagnoses has begun to plateau, providing the first tangible evidence that infrastructure development can decouple agricultural livelihoods from the risk of kidney failure.

Reverse Osmosis Water Supply Wells and The Reduction of Incidence of CKDu in the North central Province (Source: Kidney disease, health, and commodification of drinking water: An anthropological inquiry into the introduction of reverse osmosis water in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka by de Silva and Albert 2021)

Indispensability of RO plants

While large-scale projects provide a long-term solution, the ‘interim’ role of community-based Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants remains indispensable in the Northwestern hinterlands. These plants, often managed by local community-based organizations (CBOs) with technical oversight from the government, serve as the primary defence for remote settlements that the pipe-borne network has yet to reach. The operational success of these RO plants is increasingly tied to a new model of ‘Water Safety Trust.’

Surveys conducted in 2025 indicate that the reduction of CKD in these areas depends heavily on consistent maintenance; when filters are changed regularly and brine disposal is managed correctly, the resulting ‘soft’ water significantly reduces the metabolic stress on the kidneys of the local farming population. However, the province still faces the challenge of ‘water commodification,’ where the cost of filtered water can occasionally burden the poorest families, highlighting the need for continued state subsidies to ensure that clean water remains a universal right rather than a luxury.

The reduction of CKD in the Northwestern Province is also being driven by a more sophisticated integration of water management and occupational health. Recent initiatives have begun to combine the provision of clean water with ‘cool zones’ and hydration advocacy for farmers working in the intensive heat of the dry zone. There is an increasing understanding that it is not just the quality of water that matters, but the quantity and timing of consumption to prevent the sub-clinical acute kidney injuries that precede chronic failure. By 2026, the regional health authorities have integrated water quality testing with mobile renal screening,

creating a data-driven approach where water projects are prioritized for ‘red-zone’ villages showing the highest incidence of early-stage disease. This holistic strategy marks a transition from viewing CKD as a medical mystery to treating it as a manageable environmental health hazard, with the Northwestern Province serving as a vital testing ground for these integrated interventions.

Biochemical landscape

The biochemical landscape of the Northwestern Province’s water crisis is defined by a sophisticated and lethal interaction between naturally occurring minerals and the human renal system. At the molecular level, the primary concern is the synergistic effect of fluoride ions and water hardness, which is predominantly caused by high concentrations of calcium and magnesium cations. While fluoride is often discussed in isolation, recent research in 2025 and 2026 emphasizes that its toxicity is profoundly amplified when it enters the body through ‘very hard’ water (typically exceeding 180 mg/L of calcium carbonate). When these ions meet in the slightly alkaline environment of the kidney’s proximal tubules, they can form insoluble nanocrystals of calcium fluoride or fluorapatite. These microscopic precipitates act as physical irritants, causing mechanical clogging and chronic inflammation of the delicate tubular basement membranes, eventually leading to the interstitial fibrosis that characterizes CKDu.

Furthermore, the ‘Northwestern profile’ of groundwater often includes the presence of glyphosate—a common herbicide—which scientists now believe acts as a carrier or ‘chelating agent.’ Glyphosate has the chemical ability to bind with calcium and magnesium ions in hard water, forming stable complexes that may protect the toxic elements from being filtered out by the body’s natural defences, allowing them to reach the kidneys in higher concentrations. This ‘Trojan Horse’ mechanism suggests that the disease is not caused by a single pollutant, but by a geochemical cocktail where the hardness of the water essentially ‘primes’ the body to be more susceptible to other environmental toxins. Interestingly, some studies have noted that magnesium-rich water may actually offer a slight protective effect compared to calcium-dominant water, suggesting that the specific ratio of minerals in a village’s well could determine its status as a ‘hotspot’ or a safe zone.

To combat these complex interactions, the maintenance of Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants has become a cornerstone of rural health policy, though it remains fraught with logistical challenges. As of 2026, the Ministry of Health has moved toward a ‘Uniform Regulation and Training’ model to address the high variability in water quality produced by community-managed plants. Without precise maintenance, RO membranes can become ‘fouled’ by the very minerals they are designed to remove, leading to a precipitous drop in filtration efficiency. Policy experts now advocate for a ‘Public-Private-Community Partnership’ where the government provides the technical sensors and remote monitoring technology, while local organizations handle day-to-day operations. This ensures that the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) levels remain consistently below the 30-ppm threshold required to effectively ‘reset’ the mineral balance for residents who have spent decades consuming the region’s hazardous groundwater.

Fruitful environmental intervention

Ultimately, the reduction of CKD in the Northwestern Province is a testament to the power of targeted environmental intervention. By treating the water supply as a biological variable rather than just a utility, Sri Lanka is creating a global blueprint for managing ‘geogenic’ diseases. The transition from the ‘shallow regolith aquifers’—which are highly susceptible to both natural mineral leaching and agricultural runoff—to deeper, treated surface water sources represents the most significant shift in the province’s public health history. As these infrastructure projects reach completion, the hope is that the next generation of farmers in Kurunegala and Puttalam will be the first in decades to work their land without the looming shadow of a silent, water-borne epidemic.

Opinion

U.S. foreign policy double standards and Iran’s Iron theocracy

The world’s most theatrical stage

Welcome to the Grand Circus

If global geopolitics were a TV show, it would be cancelled after the first season for being too unbelievable. Consider the plot: the world’s largest arms exporter lectures others about peace; a government that executed over 500 people in a single year tells its citizens it governs by divine law; and international bodies created to enforce rules seem to apply those rules with remarkable … flexibility. Welcome to the real world of international relations, where the rules are made up and the principles don’t matter.

If global geopolitics were a TV show, it would be cancelled after the first season for being too unbelievable. Consider the plot: the world’s largest arms exporter lectures others about peace; a government that executed over 500 people in a single year tells its citizens it governs by divine law; and international bodies created to enforce rules seem to apply those rules with remarkable … flexibility. Welcome to the real world of international relations, where the rules are made up and the principles don’t matter.

This analysis examines two of the most consequential actors shaping global instability today: the United States of America, a democracy that can’t quite decide whether it believes in democracy, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, a theocracy that has perfected the art of punishing its own people for simply existing.

Episode I: The United States, ‘Do as I Say, Not as I Do’

The Democracy Export Business

The United States has, for decades, positioned itself as the global guardian of democracy, freedom, and human rights. It is a noble brand. The marketing budget alone, in the form of military expenditure at $886 billion in 2023, is staggering. And yet, the product being sold and the product being delivered have often been … different things.

The CIA-backed coup of 1953, codenamed Operation Ajax, removed Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and reinstated the autocratic Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, primarily to protect Anglo-American oil interests.

Nuclear Exceptionalism: The World’s Worst-Kept Secret

The United States currently holds approximately 5,044–5,177 nuclear warheads (depending on the source and year), while Russia being the largest with a stockpile estimated at approximately 5,580 warheads. yet it leads international campaigns demanding that other nations not develop nuclear weapons. This is a bit like the world’s most heavily armed person standing at the door of a gun shop, telling customers they cannot purchase firearms.

Furthermore, Israel is widely believed to possess 80–90 nuclear warheads. The United States has never imposed sanctions on Israel for this. India and Pakistan, both outside the NPT, were rewarded with nuclear cooperation deals after the tested nuclear weapons.

The Saudi Arabia Paradox

Perhaps, no relationship illustrates U.S. foreign policy hypocrisy more vividly than Washington’s alliance with Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom is an absolute monarchy with no elections, no free press, where women were legally barred from driving until 2018, and where the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, carried out, according to U.S. intelligence, on orders from Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, resulted in … arms sales continuing and diplomatic ties intact.

The United States sold Saudi Arabia over $37 billion in arms between 2015 and 2020, weapons used in a Yemen war that the United Nations described as one of the world’s worst humanitarian catastrophes. Yet the U.S. simultaneously held press conferences about human rights. The cognitive dissonance is not a bug. It is the feature.

Iraq: The Weapons of Mass Distraction

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq on the basis of alleged weapons of mass destruction (WMD) that did not exist. The invasion resulted in an estimated 150,000–1,000,000 Iraqi civilian deaths depending on methodology, the displacement of millions, the destabilization of an entire region, and the rise of the Islamic State, none of which appeared in the original brochure. The officials responsible for this foreign policy catastrophe faced no international tribunal. No sanctions were imposed on the United States. Several architects of the war are today respected media commentators.

Meanwhile, the International Criminal Court (ICC), an institution the United States has never ratified, is expected to hold others to account for far lesser offenses. As of 2024, the U.S. has actively sanctioned ICC officials who attempted to investigate American personnel for potential war crimes in Afghanistan.

Episode II: Iran, The People’s Nightmare

Iran’s political system is built on the concept of Velayat-e Faqih, the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, a political-theological doctrine holding that a senior Islamic cleric should govern society. In practice, this means that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, unelected by the general public, holds veto power over all branches of government, controls the military, the judiciary, state media, and the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The elected president, whether ‘moderate’ or ‘hardliner’, operates within a system where real power resides with the Supreme Leader and an unelected Guardian Council that vets all candidates and can disqualify anyone it deems insufficiently Islamic. In the 2021 presidential election, the Guardian Council disqualified over 590 candidates out of 592 who applied. The word ‘election’ is being used loosely here.

Women’s Rights: A Systematic Dismantling

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iranian women have endured one of the most comprehensive rollbacks of rights in modern history. Within weeks of the revolution, mandatory hijab laws were imposed, women were barred from serving as judges, and the minimum marriage age for girls was reduced to 9 years (later revised to 13 in 1982). This was not incidental policy; it was ideological architecture.

Today, Iranian women face legal discrimination across virtually every domain. Under the Iranian Civil Code, a woman’s testimony in court counts as half that of a man’s. Women cannot travel abroad without the written permission of their husband or male guardian. Married women cannot work without spousal consent in many circumstances. The diyeh (blood money) for a woman’s life is legally valued at half that of a man.

In September 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa (Zhina) Amini died in the custody of Iran’s Morality Police, after being arrested for allegedly wearing her hijab improperly. Her death triggered the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, one of the largest protest movements in Iranian history. The government’s response was to kill over 500 protesters, arrest more than 19,000, and execute at least four people in connection with the protests by early 2023.

The IRGC and State-Sponsored Repression

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is a military-economic-political entity unlike any other in the region. It controls an estimated 20–40% of Iran’s economy through businesses, construction contracts, and import monopolies. It commands proxy militias across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. And it suppresses domestic dissent with a ruthlessness that has drawn consistent condemnation from United Nations human rights bodies.

Amnesty International’s 2022-2023 annual report documented the IRGC and security forces using live ammunition, birdshot, and metal pellets against protesters, deliberately targeting eyes, resulting in hundreds being blinded. The UN Special Rapporteur on Iran documented ‘serious, widespread and systematic human rights violations’ constituting potential crimes against humanity.

Episode III: Where the Two Hypocrisies Meet

The relationship between the United States and Iran is, in many ways, a story of two entities who deserve each other in the sense that the behavUior of each government has fed the domestic narrative of the other for decades.

Washington uses Iran as justification for its military presence in the Gulf, its arms sales to autocratic Gulf states, and its general posture as indispensable regional hegemon. Tehran uses American hostility and sanctions as justification for economic failure, political repression, and nuclear advancement. Both governments’ hard-liners need each other to remain in power.

The Iranian people, 85 million of them, majority under 35, highly educated, and overwhelmingly wanting engagement with the world, are trapped between a government that treats them as subjects and an international sanctions regime that punishes them for their government’s choices. The American people, meanwhile, continue paying for a foreign policy architecture that serves arms manufacturers, defense contractors, and geopolitical abstractions more than it serves democratic values or human security.

Some Uncomfortable Truths

The United States is not the villain of every story, nor is Iran irredeemably authoritarian in the hearts of its people. What is consistent, and what this analysis has documented, is that both governments operate by standards they refuse to apply to themselves.

Tehran’s theocratic governance has failed its population economically, politically, and most visibly in its treatment of women and dissidents. The Woman, Life, Freedom movement showed the world what Iranian society wants. The government’s violent response showed the world what the Islamic Republic fears.

The lesson, uncomfortable as it is, is that powerful states, whether wielding aircraft carriers or theology, tend to exempt themselves from the rules they want others to follow. The only antidote is an informed public that refuses to accept these double standards as the natural order of things. Read critically. Follow the money. And remember: when a government tells you it acts in the name of God or democracy.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

News7 days ago

News7 days ago‘IRIS Dena was Indian Navy guest, hit without warning’, Iran warns US of bitter regret

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoSri Lanka evacuates crew of second Iranian vessel after US sunk IRIS Dena