Features

The Colombo Aligned Summit

In the latter half of the 20th century, the Non-Aligned Movement played an important role at a time when East-West tensions were running high. In August 1976, Sri Lanka hosted the 5th Non-Aligned Summit in Colombo. This was one of the high points in Sri Lanka’s international relations. Here, we publish an extract from Leelananda De Silva’s autobiographical volume – The Long Littleness of Life – his Memoir of Government, the United Nations, family and friends.

Sometime in 1973, Mrs. Bandaranaike, the Prime Minister, directed that I should be in charge of the economic side of the Non Aligned Summit (NAS), to be held in 1976 in Colombo. She was anxious to attach a high profile to economic issues in non aligned discussions. This was for two reasons. The first was that she wanted to make the NAS clearly more non-aligned, getting rid of the extreme anti western rhetoric of previous conferences, which was partly due to the focus on political issues. Talking economics, specially at a time when the North-South dialogue was a dominant feature in international relations made great sense. The second reason was that she felt that greater attention to international economic issues would better relate the Summit proceedings to Sri Lanka’s own economic interests. As I advised her, it was necessary to focus on relevant economic issues for Sri Lanka, instead of merely following earlier Non Aligned economic agendas where issues like transnational corporations and the New International Economic Order were focused upon. These issues were pushed by countries like Cuba and Algeria, as these were aimed at attacking the United States and other Western countries. Thereafter, my engagement with non aligned issues became my central task, during my Planning Ministry years. Between 1973 and 1977, 1 was working as much with the Foreign Ministry as with the Planning Ministry.

The Fifth Non Aligned Summitheldin 1976 was the culmination of a long process which started with the Fourth Summit in Algiers in 1973. The Prime Minister led the delegation to Algiers and the other members were Felix Dias Bandaranaike, Mrs. Lakshmi Dias Bandaranaike, Shirley Amarasinghe (Permanent Representative to the UN in New York), W.T. Jayainghe (Permanent Secretary of Foreign Affairs), Susantha De Alwis (Permanent Representative to the UN in Geneva) and myself. This delegation constituted many of the key persons who were responsible for the substantive preparations of the Colombo Summit. The other two persons who were not there were Arthur Basnayaka and Izeth Hussain. The Algiers Conference was a grand affair and was held in a newly constructed palatial conference hall. One of the things that struck me most was that the Conference was not organized well. During the week we were there, the conference sessions were held in the night, and during the day we had our rest. This made most of the delegates very tired. Mrs. Bandaranaike suggested to the delegation that we should observe the way in which the Conference was organized in Algiers. There was nothing much to learn from them.

I was looking after the Economic Committee and it was being chaired by Ambassador Hernan Santa Cruz of Chile, a leading personality of the time in international affairs. I remember working closely with the Ambassador from India, K.B. Lall, who was later to lose out to Gamani Corea, in the UNCTAD Secretary General stakes. The work of the Economic Committee was dominated by Algerian pressures to obtain support for the Opec oil price hike which had just occurred, raising the price of oil from US $4 to $13. This was a great shock to poorer developing countries. The Algerians and other oil suppliers manipulated the Summit to obtain a clear endorsement of the Opec position, although it was the poorer developing countries which paid a heavy price for the oil price hike. Opec promised that they would support schemes to obtain better prices for other commodities, but this- never happened, apart from unrealistic resolutions to change the world economic order. The Opec countries started to push for a New International Economic Order which was later adopted by the United Nations in 1974. Layachi Yaker, the Algerian Minister of Trade was the key figure organizing this Opec campaign in the non aligned context (he was later to be the head of the UN Economic Commission for Africa).

I was looking after the Economic Committee and it was being chaired by Ambassador Hernan Santa Cruz of Chile, a leading personality of the time in international affairs. I remember working closely with the Ambassador from India, K.B. Lall, who was later to lose out to Gamani Corea, in the UNCTAD Secretary General stakes. The work of the Economic Committee was dominated by Algerian pressures to obtain support for the Opec oil price hike which had just occurred, raising the price of oil from US $4 to $13. This was a great shock to poorer developing countries. The Algerians and other oil suppliers manipulated the Summit to obtain a clear endorsement of the Opec position, although it was the poorer developing countries which paid a heavy price for the oil price hike. Opec promised that they would support schemes to obtain better prices for other commodities, but this- never happened, apart from unrealistic resolutions to change the world economic order. The Opec countries started to push for a New International Economic Order which was later adopted by the United Nations in 1974. Layachi Yaker, the Algerian Minister of Trade was the key figure organizing this Opec campaign in the non aligned context (he was later to be the head of the UN Economic Commission for Africa).

The great event of the Conference, in effect, took place outside Algiers. Salvador Allende, the President of Chile was overthrown and killed in a coup led by General Pinochet during the week of the Conference. Chile under Allende had emerged as an icon standing up to US hegemony in Latin America and generally in the third world. Many of the non aligned delegations were shocked by what happened in Chile. Hernan Santa Cruz, who was chairing the Economic Committee, was the living embodiment of the Chilean crisis and he was not to go back to his country fora long time. One unforgettable memory that I have of this Summit was our departure from Algiers airport. Waiting for our respective planes, along with Mrs. Bandaranaike, were Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and President Houari Boumedienne of Algeria was there to wish us goodbye.

The most important objective for Sri Lanka at Algiers was to get the Summit to endorse Colombo as its next venue. Whether this would be done was not at all certain. To the great delight of Mrs. Bandaranaike, the Algiers Summit confirmed Colombo as the venue for the Fifth Summit. This was the start of the preparatory process. Mrs. Bandaranaike was anxious that economic issues, particularly in a North- South context, should be equally placed with political issues on the NAS agenda. This was my task in the next four years, and those preparations were pursued largely in UN multilateral forums, which were then brought into convergence at the NAS. The story of my involvement with these North- South issues will be related in another chapter. Here, I will confine myself to non aligned forums.

After the Algiers Summit and prior to the Summit in Colombo, I attended three non aligned meetings held in Dakar (Senegal), Lima (Peru) and Algiers. The Dakar and Lima meetings were at Foreign Ministers level. Apart from myself, others on the delegations were Felix Dias Bandaranaike, Shirley Amarasinghe, and Arthur Basnayaka. The Dakar meeting was held outside the main city in a newly built conference hall, in the middle of nowhere. One night, Shirley Amarasinghe, Arthur Basnayake and I had to go in a car assigned to us by the government fora late night meeting. The relations with our driver was pretty bad as he was using the official vehicle assigned to us for his own purposes. This night, on our way to the conference hall, he stopped the car in the middle of a jungle saying there was no petrol and that he was going to leave us and go to collect some petrol. This was a frightening experience. We had to forget our status and had to plead with the driver offering him some goodies to take us to the conference hall somehow. About half an hour later, he said that he had some petrol in the car and that he would use it. Anyway, we got to the conference hall and we did not see the driver again.

I was to work closely with Shirley Amarasinghe on Non Aligned issues, although he was in New York and I was in Colombo. We travelled together for many meetings and met often in New York and in Colombo. I enjoyed working with Shirley Amarasinghe. Shirley had held the highest offices of government, being appointed as Secretary to the Treasury at the age of 47. One day in Dakar he told me that when Felix Dias Bandaranaike had to leave the Finance Ministry in 1962, he also had to leave his post of Treasury Secretary. He had thought of retiring from the public service and his brother Clarence who ran the leading motor firm Car Mart had asked him to come and take over the running of the company. He was seriously considering moving to the private sector. At this point, Mrs. Bandaranaike and N.Q. Dias who was the Secretary of the Ministry of Defence and Foreign Affairs had asked him whether he would like to move into the diplomatic service and proceed to New Delhi as High Commissioner. His whole life changed with that decision to go to New Delhi at the age of 50. For the next 17 years until his death, he was a leading figure in UN circles and latterly as Chairman of the Law of the Sea Conference.

I remember another amusing incident. Over the weekend in Dakar, Arthur Basnayake, whose academic background was geography, wished to go to the interior of Senegal by train. He wanted to go alone, and there was a train going to that place. So I accompanied Arthur to the railway station. The Dakar main railway station was totally deserted and there was no train in sight. We walked down the long platform and there was a man seated at the end of it, smoking a cigar. We asked him whether we could see the station master. He said he was the station master. We asked him about the train, which was scheduled to leave that morning. He told us that was a good question, as yesterday’s train had not yet left. He suggested to us that we take the bus outside the station to our destination, as that will get us there sooner. The bus was run by the station master’s son, and to get business for the bus, it was in the interest of father and son to see that the trains were delayed.

The meeting at Lima, Peru had the usual agendas and the usual speeches. What was more interesting was the coup that took place while we were in Lima. On the Monday morning of the conference, it was ceremonially opened by General Morales, the Military Dictator of Peru. On the Wednesday morning, as we were leaving for the conference, we were informed that we should stay in the hotel as a coup had taken place and there was a curfew. The conference met again the day after and it was wound up on the weekend. When it was wound up, the new military ruler came to declare the conference closed. The host Government Peru insisted that the former dictator Morales’s name should not be mentioned in the communique and he should not be thanked for opening the conference. This was non aligned politics at its best.

The mechanism for pursuing non aligned agendas was the Coordinating Bureau of the Non Aligned Countries Meeting at Foreign Minister’s level. I attended a meeting in Algiers of the Bureau in early 1976. The task of the Sri Lankan delegation was to keep the Bureau informed of our preparations in Colombo. I remember this meeting for one poignant reason. Although Chile had a military government now, the Non Aligned Bureau, still recognized the Allende government of Chile. Its Foreign Minister Orlando Letelier, suave, elegant and the perfect diplomat, was there in Algiers. I had a cup of tea with him and discussed the forthcoming Conference in Colombo, which he expected to attend. About a month later, he was gunned down in the streets of Washington D.C. in broad daylight, a murder which had ramifications the world over.

Let me now briefly set out my observations of the NAS in Colombo. I was appointed by the Prime Minister to be Secretary of the Economic Committee of the Conference. By virtue of my position, I chaired an inter-ministerial committee on economic issues for the NAS in Colombo. We met a few times but it was not productive in shaping an economic agenda from Sri Lanka’s point of view. This had to be done by the Planning Ministry. One of the first things I had to do was to provide an input into the Prime Minister’s speech for the Conference. After discussing with the Prime Minister and with Felix Dias Bandaranaike, I submitted two proposals- one for a Countervailing Third World Currency and the other for the establishment of a Third World Commercial and Merchant Bank. The first proposal for a third world currency was a political one, to please radicals like Cuba. The second proposal was one I had developed and discussed with the Prime Minister. She liked the proposal which was pragmatic, and this was included in her speech. The Summit adopted the proposal and was later to be followed up by UNCTAD. I was asked by UNCTAD to come over to Geneva to prepare a paper on this proposal which I did in May 1977.

I am proud of this proposal, with which Mrs. Bandaranaike agreed. She wanted a high profile for economic issues, as they related to her own domestic concerns. People could relate to food and agriculture and pharmaceuticals in a way that they do not relate to Arab- Israel or East West political confrontations. The proposal fora Bank, which had merchaht banking functions, was modelled on the experience of the Crown Agents in London. Most developing countries at the time did not have the expertise and the skills to get the best terms from exporting and importing transactions. It was found at that time that Sri Lanka was purchasing commodities like oil, rice and wheat, when prices were high in a volatile world market; and full of stocks locally when the prices were low in world markets (at a time when we should be buying). A central facility for developing countries would enable them to obtain large gains through combined purchasing and other means. The bank could also handle many financial transactions of borrowing and obtaining export credits. An institution of this kind is still relevant in today’s world for many of the smaller developing countries.

Prof. Senaka Bibile had made his mark through his proposals for rationalization of pharmaceutical supplies and the purchase of non- branded, generic products for national health services. Such arrangements reduced the costs of medical supplies. Senaka Bibile was known to Mrs. Bandaranaike. She suggested to me that I should have him on the delegation to work with me in the Economic Committee to develop his ideas through a resolution which would then be applicable to the developing countries in general. Senaka Bibile worked with me at the Conference to get the resolution drafted, and we had to do some lobbying among the delegations. I found that most countries welcomed the proposals on pharmaceuticals and there was no problem in getting a strong resolution adopted. This is a resolution which had clear implications for health policies in countries like Sri Lanka. It was a delight to have worked with Senaka Bibile.

The NAS was a historic event and it should be remiss of me if I did not mention the others who were associated closely with the NAS, as I had personal knowledge of the event. In organizing an NAS on this scale, Sri Lanka was punching above its weight in international relations. Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the Prime Minister, was primarily responsible for the success of the Summit. She personally supervised many of its key aspects. Felix Dias Bandaranaike and Shirley Amarasinghe were actively engaged in most of the preparatory work between 1973 and 1976. They were persons of international standing and were highly respected, and with Mrs. Bandaranaike, were responsible for a highly acclaimed Summit. W.T Jayasinghe , the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Basnayake, Director General of the Foreign Ministry and Izeth Hussein, Director of the Non Aligned desk at the Foreign Ministry were key figures in the preparations on the political side. Susanta De Alwis who was our ambassador in Geneva, was the secretary of the political committee, and he and I being secretaries of the two committees had to interact closely to avoid possible conflicts in conference proceedings and resolution drafting. Neville Kanakarathne can be added to this list. Izeth Hussein made a distinctive contribution in drafting what was considered an outstanding Political Declaration which captured the essence of Non-Alignment.

Dr. Mackie Ratwatte, was the man in charge of the organizational side of the Conference. He was assisted by several Foreign Office officials, specially Ben Fonseka. Manel Abeysekara managed a flawless protocol operation with finesse and flair. This aspect of the Summit was crucial, as delegations with Heads of Governments and State are sensitive to their treatment by the host country. Vernon Mendis, who was then the High Commissioner in London, was brought to Colombo to act as Secretary General of the Conference, as W. T Jayasinghe and Arthur Basnayake declined to undertake that role, Vernon’s role was to assist the Prime Minister during the Conference proceedings. Dharmasiri Peiris, Secretary to the Prime Minister, worked behind the scenes over this entire four year period and was guide and adviser to the Prime Minister on many NAM issues, and ran her office at the Conference, where many questions had to be addressed on an urgent basis. He was associated with Nihal Jayawickrama, Secretary to the Ministry of Justice and Sam Sanmuganathan, Secretary to the Ministry of Constitutional Affairs On the economic side I received much assistance from Wilfred Nanayakkara, Deputy Director of the Economic Affairs Division in the Ministry of Planning. Lakdasa Hulugalle, an outstanding economist working with UNCTAD and an authority on North South issues was in regular contact, and was a great source of advice during the Summit. Havelock Brewster, a well known Caribbean economist from UNCTAD worked with the Economic Committee, at my request. He was actively involved in the drafting of the large number of economic resolutions which came up at the Conference.

Let me divert here to record my recollections of two episodes connected with the Summit as they are instructive and should not be forgotten. First was Mrs. Bandaranayaike’s decision to vacate ” Temple Trees” so that Mrs. Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India could occupy it during her visit to Colombo. At this time, Indo- Sri Lanka relations were at a low ebb, due to Sri Lanka’s assistance to Pakistan during the Bangladesh crisis. Mrs. Bandaranaike wanted to signal her closeness to India and also her personal regard for Mrs. Gandhi by this gesture. That was a master stroke in bilateral relations. The second was with regard to Kurt Waldheim, the Secretary General of the UN. He was in Colombo accompanied by Dr. Gemini Corea, who was Secretary General of UNCTAD. He expected to address the Non Aligned Summit, of Heads of Government. There were many who were opposed to Waldheim addressing the Summit and preferred him to address the Foreign Minister’s Conference the previous week. It is my recollection that Waldheim in the end addressed the Summit. In 1976, the Secretary General of the UN was not regarded as an equal to Heads of Government.

The Colombo Summit was attended by over 60 Heads of Government and I remember seeing most of them either in the Conference hall or outside. There were Anwar Sadat of Egypt, Gadaffi of Libya, and Marshall Tito of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was one of the key countries in Non Aligned and Third World organizations, and it is astonishing that 20 years later Yugoslavia is no more. I remember standing next to Tito as the national anthem was being sung to bring the Summit to an end. He had gone out of the hall and had just come in and I happened to be standing next to him. Apart from the Heads of Government, there were many other Foreign Ministers and high officials I came in contact with in the course of my work on the Economic Committee. It is a long time and I forget their names.

After the Summit, in early 1977, Felix Dias Bandaranaike, Sherley Amarasinghe, Arthur Basnayake, Izeth Hussein and I were the delegation to the Non Aligned Foreign Ministers meeting in New Delhi. Mrs. Gandhi had lost the election and there was a new BJP government. Mrs. Bandaranaike had asked the Sri Lanka delegation to meet with Mrs. Gandhi, informally at her residence. This was not at all appreciated by the new Indian Government. That was the last time I was to see Mrs. Gandhi, having seen her on many occasions in the last 6 years. This was also my last non aligned meeting, as Mrs. Bandaranaike lost the election later in the year and a new government came in.

Features

The invisible crisis: How tour guide failures bleed value from every tourist

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

If you want to understand why Sri Lanka keeps leaking value even when arrivals hit “record” numbers, stop staring at SLTDA dashboards and start talking to the people who face tourists every day: the tour guides.

They are the “unofficial ambassadors” of Sri Lankan tourism, and they are the weakest, most neglected, most dysfunctional link in a value chain we pretend is functional. Nearly 60% of tourists use guides. Of those guides, 57% are unlicensed, untrained, and invisible to the very institutions claiming to regulate quality. This is not a marginal problem. It is a systemic failure to bleed value from every visitor.

The Invisible Workforce

The May 2024 “Comprehensive Study of the Sri Lankan Tour Guides” is the first serious attempt, in decades, to map this profession. Its findings should be front-page news. They are not, because acknowledging them would require admitting how fundamentally broken the system is. The official count (April 2024): SLTDA had 4,887 licensed guides in its books:

* 1,892 National Guides (39%)

* 1,552 Chauffeur Guides (32%)

* 1,339 Area Guides (27%)

* 104 Site Guides (2%)

The actual workforce: Survey data reveals these licensed categories represent only about 75% of people actually guiding tourists. About 23% identify as “other”; a polite euphemism for unlicensed operators: three-wheeler drivers, “surf boys,” informal city guides, and touts. Adjusted for informal operators, the true guide population is approximately 6,347; 32% National, 25% Chauffeur, 16% Area, 4% Site, and 23% unlicensed.

But even this understates reality. Industry practitioners interviewed in the study believe the informal universe is larger still, with unlicensed guides dominating certain tourist hotspots and price-sensitive segments. Using both top-down (tourist arrivals × share using guides) and bottom-up (guides × trips × party size) estimates, the study calculates that approximately 700,000 tourists used guides in 2023-24, roughly one-third of arrivals. Of those 700,000 tourists, 57% were handled by unlicensed guides.

Read that again. Most tourists interacting with guides are served by people with no formal training, no regulatory oversight, no quality standards, and no accountability. These are the “ambassadors” shaping visitor perceptions, driving purchasing decisions, and determining whether tourists extend stays, return, or recommend Sri Lanka. And they are invisible to SLTDA.

The Anatomy of Workforce Failure

The guide crisis is not accidental. It is the predictable outcome of decades of policy neglect, regulatory abdication, and institutional indifference.

1. Training Collapse and Barrier to Entry Failure

Becoming a licensed National Guide theoretically requires:

* Completion of formal training programmes

* Demonstrated language proficiency

* Knowledge of history, culture, geography

* Passing competency exams

In practice, these barriers have eroded. The study reveals:

* Training infrastructure is inadequate and geographically concentrated

* Language requirements are inconsistently enforced

* Knowledge assessments are outdated and poorly calibrated

* Continuous professional development is non-existent

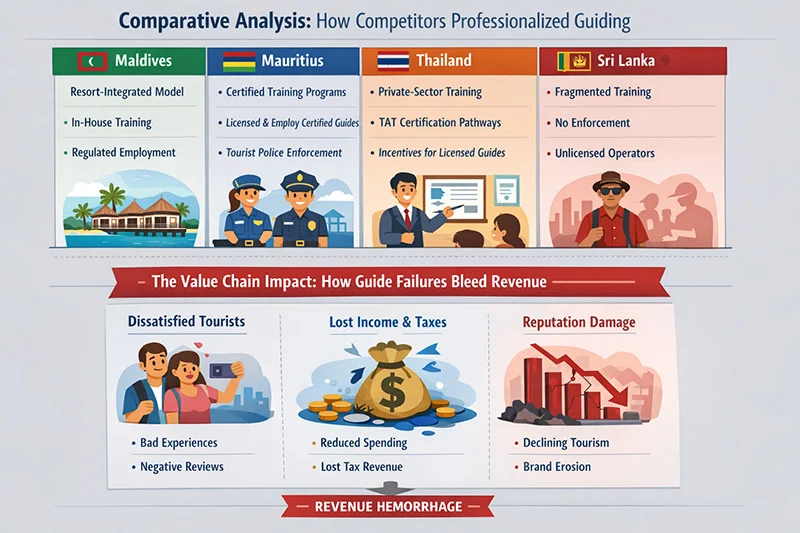

The result: even licensed guides often lack the depth of knowledge, language skills, or service standards that high-yield tourists expect. Unlicensed guides have no standards at all. Compare this to competitors. In Mauritius, tour guides undergo rigorous government-certified training with mandatory refresher courses. The Maldives’ resort model embeds guide functions within integrated hospitality operations with strict quality controls. Thailand has well-developed private-sector training ecosystems feeding into licensed guide pools.

2. Economic Precarity and Income Volatility

Tour guiding in Sri Lanka is economically unstable:

* Seasonal income volatility: High earnings in peak months (December-March), near-zero in low season (April-June, September)

* No fixed salaries: Most guides work freelance or commission-based

* Age and experience don’t guarantee income: 60% of guides are over 40, but earnings decline with age due to physical demands and market preference for younger, language-proficient guides

* Commission dependency: Guides often earn more from commissions on shopping, gem purchases, and restaurant referrals than from guiding fees

The commission-driven model pushes guides to prioritise high-commission shops over meaningful experiences, leaving tourists feeling manipulated. With low earnings and poor incentives, skilled guides exist in the profession while few new entrants join. The result is a shrinking pool of struggling licensed guides and rising numbers of opportunistic unlicensed operators.

3. Regulatory Abdication and Unlicensed Proliferation

Unlicensed guides thrive because enforcement is absent, economic incentives favour avoiding fees and taxes, and tourists cannot distinguish licensed professionals from informal operators. With SLTDA’s limited capacity reducing oversight, unregistered activity expands. Guiding becomes the frontline where regulatory failure most visibly harms tourist experience and sector revenues in Sri Lanka.

4. Male-Dominated, Ageing, Geographically Uneven Workforce

The guide workforce is:

* Heavily male-dominated: Fewer than 10% are women

* Ageing: 60% are over 40; many in their 50s and 60s

* Geographically concentrated: Clustered in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Cultural Triangle—minimal presence in emerging destinations

This creates multiple problems:

* Gender imbalance: Limits appeal to female solo travellers and certain market segments (wellness tourism, family travel with mothers)

* Physical limitations: Older guides struggle with demanding itineraries (hiking, adventure tourism)

* Knowledge ossification: Ageing workforce with no continuous learning rehashes outdated narratives, lacks digital literacy, cannot engage younger tourist demographics

* Regional gaps: Emerging destinations (Eastern Province, Northern heritage sites) lack trained guide capacity

1. Experience Degradation Lower Spending

Unlicensed guides lack knowledge, language skills, and service training. Tourist experience degrades. When tourists feel they are being shuttled to commission shops rather than authentic experiences, they:

* Cut trips short

* Skip additional paid activities

* Leave negative reviews

* Do not return or recommend

The yield impact is direct: degraded experiences reduce spending, return rates, and word-of-mouth premium.

2. Commission Steering → Value Leakage

Guides earning more from commissions than guiding fees optimise for merchant revenue, not tourist satisfaction.

This creates leakage: tourism spending flows to merchants paying highest commissions (often with foreign ownership or imported inventory), not to highest-quality experiences.

The economic distortion is visible: gems, souvenirs, and low-quality restaurants generate guide commissions while high-quality cultural sites, local artisan cooperatives, and authentic restaurants do not. Spending flows to low-value, high-leakage channels.

3. Safety and Security Risks → Reputation Damage

Unlicensed guides have no insurance, no accountability, no emergency training. When tourists encounter problems, accidents, harassment, scams, there is no recourse. Incidents generate negative publicity, travel advisories, reputation damage. The 2024-2025 reports of tourists being attacked by wildlife at major sites (Sigiriya) with inadequate safety protocols are symptomatic. Trained, licensed guides would have emergency protocols. Unlicensed operators improvise.

4. Market Segmentation Failure → Yield Optimisation Impossible

High-yield tourists (luxury, cultural immersion, adventure) require specialised guide-deep knowledge, language proficiency, cultural sensitivity. Sri Lanka cannot reliably deliver these guides at scale because:

* Training does not produce specialists (wildlife experts, heritage scholars, wellness practitioners)

* Economic precarity drives talent out

* Unlicensed operators dominate price-sensitive segments, leaving limited licensed capacity for premium segments

We cannot move upmarket because we lack the workforce to serve premium segments. We are locked into volume-chasing low-yield markets because that is what our guide workforce can provide.

The way forward

Fixing Sri Lanka’s guide crisis demands structural reform, not symbolic gestures. A full workforce census and licensing audit must map the real guide population, identify gaps, and set an enforcement baseline. Licensing must be mandatory, timebound, and backed by inspections and penalties. Economic incentives should reward professionalism through fair wages, transparent fees, and verified registries. Training must expand nationwide with specialisations, language standards, and continuous development. Gender and age imbalances require targeted recruitment, mentorship, and diversified roles. Finally, guides must be integrated into the tourism value chain through mandatory verification, accountability measures, and performancelinked feedback.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Can Sri Lanka achieve high-value tourism with a low-quality, largely unlicensed guide workforce? The answer is NO. Unambiguously, definitively, NO. Sri Lanka’s guides shape tourist perceptions, spending, and satisfaction, yet the system treats them as expendable; poorly trained, economically insecure, and largely unregulated. With 57% of tourists relying on unlicensed guides, experience quality becomes unpredictable and revenue leaks into commission-driven channels.

High-yield markets avoid destinations with weak service standards, leaving Sri Lanka stuck in low-value, volume tourism. This is not a training problem but a structural failure requiring regulatory enforcement, viable career pathways, and a complete overhaul of incentives. Without professionalising guides, high-value tourism is unattainable. Fixing the guide crisis is the foundation for genuine sector transformation.

The choice is ours. The workforce is waiting.

This concludes the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation. The diagnosis is complete. The question now is whether policymakers have the courage to act.

For any concerns/comments contact the author at saliya.ca@gmail.com

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka