Features

That Midnight Knock on the Door:Sundarampuram: Janel Piyanpath

English name: ‘Jaffna Doors and Windows’

Concept, Design, Editing: Sarath Chandrajeeva

Layout: Kanishka Vijayapura

Printed and bound by Neo Graphics Pvt (Ltd)

Sales points: Barefoot Book shop Galle road Colombo 03, Sarasavi Book shops, Sakura agencies Colombo 04, Plate Pvt. (Ltd) Colombo 03.

Selling price: Rs.10,000.00 (below cost)

by Laleen Jayamanne

Jaffna Doors and Windows is the blunt English title of a large book of multilingual poems, each written in relation to a specific photograph of bomb-blasted buildings of Jaffna during the civil war. Each poem is printed on the partnered photographic image which covers an entire page or two. At a glance the Jaffna ruins feel like a vast overgrown archaeological site, intertwined with wild creepers, tangled roots, green foliage, trees, teeming with vitality.

The project was born on the 31st January 2021 when the Sinhala poet Lal Hegoda sent his friend Hiniduma Sunil Senevi a poem and the latter responded with one himself, within 45 minutes! (I love this innate skill and impulse, which I have observed on FaceBook as well, among Sinhala poets). Then, Lal sent both poems to several friends, including Sarath Chandrajeewa.

Sarath, in turn, then decided to send a photograph from his collection of destroyed buildings of Jaffna and asked each recipient to write a poem (in any of our three languages), in relation to the image. While there are wonderful Muslim, Tamil and Sinhala poets among them, many are not poets but have felt impelled to write a poem when the request came with an image that moved them, spoke to them, perhaps even with a ‘foreign’ script like Brahmi. As the project expanded, many other photographers contributed their own images of destroyed buildings, houses, kovils, mosques, churches, etc. Fourteen photographers and 86 writers participated in the project creating 108 poems.

Thus was born, not quite a Kavi Maduwa (poetry-shed), nor exactly a Raga Mala (garland of melody), but what I like to imagine as an electronic, wild Mycelial Network (a fungal web), growing under the rubble, entwined with human bones in that blood-soaked earth of Jaffna, emerging into the sunlight like fungi (mushrooms, hathu), in all their colourful variety of shapes and sizes. Such was the chance beginnings of this interethnic, networked collective project of friendship and solidarity, expressed in this singular book, coordinated and edited by Sarath and published by The Contemporary Art & Crafts Association of Sri Lanka in October 2022.

It’s been launched in Jaffna but not in Colombo, nor even reviewed as yet. The Jaffna Doors and Windows have stories to tell, stories of fear, terror, death and destruction and systematic, well-planned theft, during the civil war years, of these valued, detachable artefacts from Tamil and Muslim homes. The Tamil title, ‘Displaced Doors and Windows’, captures this history precisely. It is this aspect of war profiteering that has galvanised many to reflect and write a poem, even though some have never done that before.

This carefully crafted ‘Artists’ Book’, must surely be of interest to institutions such as the International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Geoffrey Bawa Foundation, in particular. A book launch and a moderated discussion at any of these institutions (at the forefront of work on the cultural intersection of ethnicity with photography, poetry, art & crafts, art history and architecture), could provide a hospitable forum for ‘Truth-Telling’, enhancing the ongoing processes of ‘Reconciliation,’ after the long civil war (1983-2009).

These Doors and Windows are booty, and might well haunt the conscience of the good folk sleeping in houses well secured with them, if they did know the full story. A Southern book launch would be something of an exorcism I imagine, leading to reparation through a return of the looted precious objects, laden with generational family memories and scarred with historical trauma, varnished and polished over no doubt.

The looted Jaffna Doors and Windows are made of hardwood and crafted with traditional decorative patterns such as I have not seen in the South. Some are painted. They are palpable evidence of traditions of craft practices of Jaffna. Who were these craftsmen? Are they still alive? Are they both Muslim and Tamil? I imagine Geoffrey Bawa would have been interested in answers to these questions. I heard a formal discussion at an exhibition of Bawa’s architectural drawings once (accessed on YouTube), where Channa Daswatte mentioned pointedly that Bawa hired Muslim builders for his projects.

Clearly, these doors and windows were made to last generations, like Kandalama. And no doubt, these sturdy antique artefacts must now grace architect-designed houses in the South, especially in Colombo. These items, along with the sturdy cross beams (uluwahu), were wrenched out and transported to Colombo during the war, openly sold at a brisk pace and bought by eager architects and other middle-class folk with antiquarian interest in craft, for their cool new houses. There is a recorded instance where shop owners prevented Hegoda from photographing a stack of these doors on display at a store front, on the outskirts of Colombo with the signage, ‘Jaffna Doors and Windoors’. This was to be the impetus for Hegoda’s inaugural poem sent to Sunil, which then led to the long process of creating this collaborative and moving book.

Sundarampuram Janel Piyanpath

, the poetic title in Sinhala, is taken from Hegoda’s own poem called Hogana Pokuna (a beautiful vernacular phrase for the ocean, to those from inland who have never heard the ‘roaring’ ocean and imagine it to be a ‘pond’!). The poet muses, where the doors and windows of Jaffna might have gone to, and responds, perchance to see the Hogana Pokuna in Colombo!

Restitution of Stolen Artefacts

It would be an interesting art-historical based activist project of reclamation of a lost tradition, to try to find these doors and windows and photograph them if visible from outside. The photographs can then be components of an installation and/or the matrix for another book of trilingual poetry. Such a project would excite poets and others keen to work across the three languages and cultures and media, to create robust networks of exchange across wounding divides. Perhaps, even, the owners can be persuaded to return the stolen artefacts, which is now global best practice in art institutions and among respectable ethical collectors.

This issue reminds me of the paintings stolen by the Nazis from wealthy Jewish homes and the struggles to reclaim them by the descendants. There was a film recently about one of Klimt’s most famous paintings which, after a legal drama, was finally given to its rightful inheritor. Of course, these beautifully crafted or even purely functional solid doors don’t share the aesthetic and monetary values of high modernist European art, but given the revival of Lankan arts & crafts in the wake of Bawa’s visionary, celebrated project, those astute architects who formulated and activated the idea of ‘Tropical Modernism’ might take up this activist project as a challenge in Lanka now. It could take the once radical idea out of its comfort zone of South Asian cool and give it a further ethical resonance for the region too.

When flicking through the book full of colour, with the profuse green foliage, the splashes of abstract colours on the pages, the intensity of sun- light, the blue sky and randomly reading a stanza or two that caught my eye, one sees the empty holes on walls, a recurring visual motif. Then, the memory of reading accounts of how Richard de Zoysa, the Lankan journalist, was taken away by government law enforcement officials, from his home one night, never to return, came to mind. Was there a knock on his door late that night? I wondered. Richard’s abduction, torture and murder brought home to the Sinhala middle classes in Colombo and those of us living outside the country, what had in fact been happening to countless unknown young persons, right across the country. Many knew Richard as a charismatic actor and fearless journalist.

I remember hearing Richard’s mother, Dr Manorani Saravanamuttu, talk about the state of terror in Sri Lanka (that of the state, the LTTE and JVP), and also about Richard’s death, at an Amnesty International meeting in Sydney in 1991 perhaps. I still remember Richard and his mother playing as mother and son in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon in Colombo, in the late 70s, in the open, perhaps at the British Council. Manorani was Clytemnestra and Richard Orestes, duty bound to kill his mother, because she killed his father, because he killed their daughter, so as to placate the wind god to set sail to sack Troy. This cycle of relentless mythic violence the mother and son enacted in the Greek tragedy, appeared to have gripped Lanka too. But the play is a part of a trilogy, which concludes with the establishment of trial by jury where the principle of Justice, rather than vengeance, is established in Athens, through argument and a spirit of reconciliation led by Athena, governed by reason. This too appears relevant to Lanka now where the state enacts vengeful violence on peaceful protestors and journalists and the independence of the judiciary is eroded.

Sundarampuram

is dedicated to Dr Rajani Thiranagama, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Jaffna, also a well-known human rights activist, who was gunned down by a member of the LTTE. There is an image in the book of her smiling at us and her long poem ‘Letter from Jaffna’, printed beside it in the three languages. Her poem describes the quotidian, ceaseless mass violence and sense of terror they all experienced caught between the IPKF, LTTE and the Lankan Army. She speaks on behalf of the nameless victims. Her sister Sumathy writes of the mass eviction of Muslims from Jaffna by the LTTE, and of their abandoned homes then subject to acts of vandalism.

Hiniduma Sunil’s poem describes the interior of a posh Colombo home where a Tamil servant-girl finds herself alone in the living room where one of those Jaffna windows and doors have landed. Her silent thoughts are given poetic expression. Priyantha Fonseka apostrophises a Jaffna window in happier times, when it opened on its intact hinges, to let in a gentle breeze in a moonlit night and the beloved. Readers will no doubt pick up poems that appeal to them from its large selection and the images themselves will lure us despite all, because they have become allegorical, like all ruins, and as such, have the power to address us with the injunction, ‘Read Me!’ ‘Say something,’ they whisper to our ears. (To be continued)

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

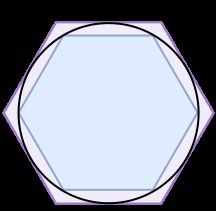

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US