Features

Television takes off; JRJ takes over ITN fathered by two of his nephews

Excerpted from vol, 2 of Sarath Amunugama’s autobiography

I visited Tokyo and had discussions with the Ministry of Finance and the Nippon Electrical Corporation [NEC] to quickly begin work on our Television complex. We could save time because it was an outright grant from Japan to thank JRJ for his memorable contribution at the Peace Conference in San Francisco. At the same time another grant was awarded at JRJ’s request for a hospital which was to become today’s Sri Jayewardenepura hospital.

Here too the President acted in his inimitable manner. He was asked to decide on the number of beds for the new hospital. He inquired from the Japanese authorities about the number of beds in their largest hospital abroad. The answer was 1000. JRJ asked for 1001 beds and the nonplussed Japanese agreed subject to their own request that the 1001st bed be permanently reserved for the use of JRJ. That was the type of ‘bon homie’ that prevailed at that time. Sri Lanka was placed high on the priority lists for technical cooperation and funding in the OECD countries as later proved in the bi-lateral funding of the Mahaweli scheme.

We organized a spectacular stone laying ceremony for the TV complex under the patronage of the President at the Colombo ladies hockey grounds which now houses Rupavahini. It was also a farewell of sorts for Ambassador Ochi who was retiring amid much appreciation from his government. Ochi, representing Japan, had missed out on funding a Mahaweli dam. The UK, Germany, Canada and Sweden had agreed to undertake those projects. So TV was Ochi’s final throw of the dice.

This was his last assignment and we made it a memorable one for him. Since Japan was identified as a Buddhist country the senior priests who were connected to the SLBC came in large numbers. They were led by Baddegama Wimalawansa, Tallale Dhammananda and Hettimulle Vajirabuddhi Theros who were held in high regard among the ‘intellectual Sangha. The President made a thoughtful speech saying that “Rupavahini should be a Satyavahini”. Ambassador Ochi replied and I gave the vote of thanks ending with a few sentences in Japanese which I had memorized the night before.

Altogether it was an impressive ceremony, and the construction work began the following day. Teams of Japanese specialists were coming in regularly and with my new Minister Anandatissa’s approval I set up a steering committee of SLBC, Film Unit, Information Department and Ministry of Finance officials under my chairmanship to monitor progress weekly. A cell was set up in the Ministry to service the steering Committee. In fact it was not too complicated an operation since this was a ‘turnkey’ project, which meant that all the construction work was undertaken by the Japanese contractor who was paid direct in Tokyo. Thus the work went on without a hitch and we were working ahead of schedule.

PAL System

At this stage I had to make a crucial decision regarding the Television transmission standard. There were three models – American, French [NTSC] and German [PAL]. This referred to the transmission and reception of the TV image. The Indian Doordharshan TV which was primitive and was transmitting black and white images to limited areas was using NTSC based on a UNESCO grant. I discussed this question with the President and decided to consult Arthur Clarke who was living in Colombo and was the father of the ‘geo stationary satellite’.

A few days later Arthur called over and advised, in no uncertain terms, that we should select the PAL option. I informed the Japanese side about our choice and, despite the fact that they used NTSC in Japan, they agreed to provide the PAL system. This has been, as later proved, to be a correct decision and the country is indebted to Arthur Clarke for his forthright and timely advice.

Pidurutalagala

Another strategic decision to be made was regarding the location of TV transmitters. Though countries with a large land mass had to depend on satellites for transmitting the signal, we were fortunate in that our topography enabled us to go for a terrestrial system. This was a great advantage both in terms of costs and easy maintenance. As Arthur Clarke said, “Sri Lanka had been designed by god for TV”. With a central hill massif and the highest point of Pidurutalagala right in the centre of it, we could erect the main tower from which the signal could radiate island-wide.

It only needed two booster towers – in Kokavil in the north and Deniyaya in the south – to reach every nook and corner of the island. This configuration which had the approval of Japanese as well as SLBC engineers, some of whom like Shantilal Nanayakkara had worked as TV engineers abroad, was decided on without much difficulty. The problem however was to take the main tower to Pedro since the top was a virgin jungle with no access.

The Japanese had suggested building a road up to the top but both my Minister and I were opposed to cutting a road as that would lead to the rape of a national treasure by timber extractors and vandals. It was while pondering the problem that I tried out a far out solution which finally worked, though it seems like the ending of a Hollywood movie. I contacted the American Embassy and diverted its 7th fleet to Colombo harbour. Giant helicopters of the 7th fleet were used to airlift the TV towers to the top of Pidurutalagala. This must be recorded as a unique service of the much maligned US navy.

Independent Television Network [ITN]

While the work on the National station was proceeding satisfactorily, Anil Wijewardene and Shan Wickremesinghe were hard at work setting up their private TV station at Mahalwarawa. Shan who had studied engineering in the UK was a genius in mechanical and engineering matters and Anil took care of the administrative side of the operation. JRJ kept an avuncular eye on the family project, meeting his nephews from time to time and asking us to monitor their progress.

Their channel was named the Independent Television Network [ITN] and an American investor joined them to help expedite the project. After a couple of years they were ready to begin transmissions well ahead of the national system [Rupavahini]. ITN soon began test transmissions which were enthusiastically viewed by Colombo society. Anil had got down popular programmes like ‘Sesame Street’ and ‘Mind your Language’ which whetted our appetite for TV.

ITN then announced that they would begin regular broadcasts which would cover a wide urban area soon. Local companies then began to sell TV reception sets mostly imported from Japan. They were all globally known brands and were based on ‘state of the art’ technology. In fact the TV sets were selling in such large numbers that it was way ahead of the projections made by UNESCO and other specialized bodies. It was suggested that some of these sets may be smuggled to India as global brands were hard to come by there.

Indian television in black and white, which was geared to educating farmers, was not very popular. Expectations on ITN were running high and we all looked forward to opening day. Later I was told that Mrs. Elina Jayewardene had invited her friends to her home for tea and TV. The President himself had joined the party. Imagine everybody’s surprise, and anger, when at the appointed hour nothing appeared on their screens. Actually what they saw was a series of white lines, which gave the effect of rain, on a black screen.

Telephones started to ring at Breamar and the President was humiliated. He called Anandatissa and asked him to take over ITN and run it properly. The Minister and all of us were embarrassed because we liked Shan and Anil as young entrepreneurs. We all had to climb out of the hole that they had dug because the public which had invested in TV sets were not interested in the niceties of the blame game. They blamed the President and his Government.

We were savvy enough to know that the family will try to make amends and get the President to rescind his order for a takeover by the Ministry. For some reason, unknown to us, JRJ refused to budge. Our guess was that Mrs. Jayewardene had put her foot down. The President’s decision was a traumatic one for his kin group. Anil’s mother who was a very smart lady, was devastated by this decision. She told me that it reminded her of the traumas inflicted on her husband, Seevali, and family by the Wijewardenes many years ago. (background note – Seevali Wijewardene was ostracized by his father, DR Wijewardene over his marriage).

I replied that JRJ had nurtured this project and had given every opportunity to his young relatives. His decision was a ‘bona fide’ one as he had to face the wrath of the public, I assured her. But she was not satisfied with my explanation. She quite rightly encouraged her son and nephew to start all over again. Anil continued to provide programmes to the reconstituted ITN and the ‘never say die’ Shan worked round the clock and set up Tele Shan which later metamorphosed into the present TNL. Anil quit along the way and Shan and his daughter Ishini ran TNL.

Given the ‘hot potato’ of ITN overnight by the President we had to scramble to salvage the operation. Since we took over ITN under the SLBC Act, I with the Minister’s concurrence, decided to appoint Thevis Guruge – the Director General of SLBC – as the Competent Authority of the network. Guruge was an ideal choice because he was a key member of our Rupavahini planning cell and a veteran of radio broadcasting. He also had a reputation as a ‘go getter’ who had the confidence of his staff.

Because of this interlocking arrangement we could easily deploy the staff and finances of SLBC to get ITN moving. It also had the advantage that we could now coordinate ITN operations with the building of Rupavahini which was already ahead of schedule. Many of the early broadcasters of TV came from SLBC while its camera and editing departments were manned by veterans from the Government Film Unit.

I had sent all Departmental heads of the GFU for training in Germany and Malaysia and outstanding technicians like Leo Wickremaratne, Sanath Liyanage and Wimal Perera and Engineers like Buell and Shantilal Nanayakkara were attached to ITN. With all that talent we took a daring decision to telecast the Independence Day celebrations of 1980 from Galle Face green. SLBC announcers led by H.M. Gunasekere and Palitha Perera were on duty, and we successfully completed our mission.

My Minister and JRJ were delighted. Thanks to the take over and the skills of our personnel we were trained and ready when Rupavahini was launched in 1982. Ochi was replaced by Ambassador Chiba who was a veteran Foreign Service Officer having served in many western capitals before being assigned to Colombo. He worked very -closely with our Ministry and Rupavahini was able to broadcast before the scheduled date.

Then the question of appointing the new Chairman arose. I strongly recommended the appointment of M.J. Perera who was a veteran CCS officer and a much admired Director of Radio Ceylon in its heyday. The President and Menikdiwela were not too happy with our proposal but went along as up to now we had piloted the operation without any problems. The appointment was made but soon I began to have reservations.

I had planned to have a lean and mean administration with productions both in- house and contracted out to many new producers who could sell their wares to Rupavahini. The rise of the ‘Independents’ was the latest approach in order to introduce variety and professionalism to TV broadcasting. MJ’s approach was quite different. As he had done in his Radio Ceylon days he wanted to concentrate power in his own hands and accommodate his loyalists who were encouraged to sing his praise.

As usual he attempted to create his own ‘comfort zone’ by surrounding himself with artistes in other fields such as the Sinhala stage who were given executive positions that they were not familiar with. He expanded the administration, even going to the extent of first building an administration block to accommodate a large number of clerks who were called ‘The Horana Horde’ since many of them came from his home town.

The idea of a new style TV was abandoned for a bureaucratic monolith which to date cannot compete with the private channels which are lean and mean and making handsome profits. State TV is at the bottom of viewer ratings and its Chairmen have had to appeal to the Treasury for funds to pay its overstaffed cadres. The latest equipment donated by Japan are not utilized and corruption is rampant, as in most state Institutions. Many years later when I was an advisor to the President, I managed to change the Board but by then it was too late. State radio and television have been rejected by the audience.

Features

A long-running identity conflict flares into full-blown war

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

The current crisis in the Middle East which was triggered off by the recent killing of Iranian spiritual head of state Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in a combined US-Israel military strike is multi-dimensional and highly complex in nature but when the history of relations between Islamic Iran and the West, read the US, is focused on the religious substratum in the conflict cannot be glossed over.

In fact it is not by accident that US President Donald Trump resorts to Biblical language when describing Iran in his denunciations of the latter. Iran, from Trump’s viewpoint, is a primordial source of ‘evil’ and if the Middle East has collapsed into a full-blown regional war today it is because of the ‘evil’ influence and doings of Iran; so runs Trump’s narrative. It is a language that stands on par with that used by the architects of the Iranian revolution in the crucial seventies decade.

In other words, it is a conflict between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ and who is ‘good’ and who is ‘evil’ in the confrontation is determined mainly by the observer’s partialities and loyalties which may not be entirely political in kind. It should not be forgotten that one of President Trump’s support bases is the Christian Right in the US and in the rest of the West and the Trump administration’s policy outlook and actions should not be divorced from the needs of this segment of supporters to be fully made sense of.

The reasons for the strong policy tie-up between Rightist administrations in the US in particular and Israel could be better comprehended when the above religious backdrop is taken into consideration. Israel is the principal actor in the ‘Old Testament’ of the Bible and is seen as ‘the Chosen People of God’ and this characterization of Israel ought to explain the partialities of the Republican Right in particular towards Israel. Among other things, this partiality accounts for the strong defence of Israel by the US.

For the purposes of clarity it needs to be mentioned here that the Bible consists of two parts, an ‘Old’ and ‘New Testament’ , and that the ‘New Testament’ or ‘Message’ embodies the teachings of Jesus Christ and the latter teachings are seen as completing and in a sense giving greater substance to the ‘Old Testament’. However, Judaism is based mainly on ‘Old Testament’ teachings and Judaism is distinct from Christianity.

To be sure, the above theological explanation does not exhaust all the reasons for the war in the Middle East but the observer will be allowing an important dimension to the war to slip past if its importance is underestimated.

It is not sufficiently realized that the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979 utterly changed international politics and re-wrote as it were the basic parameters that must be brought to bear in understanding it. So important is the Islamic factor in contemporary world politics that it helped define to a considerable degree the new international political order that came into existence with the collapsing of the Cold War and the disintegration of the USSR .

Since the latter developments ‘political Islam’ could be seen as a chief shaping influence of international politics. For example, it accounts considerably for the 9/11 calamity that led to the emergence of fresh polarities in world politics and ushered in political terrorism of a most destructive kind that is today disquietingly visible the world over.

It does not follow from the foregoing that Islam, correctly understood, inspires terrorism of any kind. Islam proclaims peace but some of its adherents with political aims interpret the religion in misleading, divisive ways that run contrary to the peaceful intents of the faith. This is a matter of the first importance that sincere adherents of the faith need to address.

However, there is no denying that the Islamic Revolution in Iran of 1979 has been over the past decades a great shaper of international politics and needs to be seen as such by those sections that are desirous of changing the course of the world for the better. The revolution’s importance is such that it led to US political scientist Dr. Samuel P. Huntingdon to formulate his historic thesis that a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ is upon the world currently.

If the above thesis is to be adopted in comprehending the principal trends in contemporary world politics it could be said that Islam, misleadingly interpreted by some, is pitting a good part of the Southern hemisphere against the West, which is also misleadingly seen by some, as homogeneously Christian in orientation. Whereas, the truth is otherwise. The West is not necessarily entirely synonymous with Christianity, correctly understood.

Right now, what is immediately needed in the Middle East is a ceasefire, followed up by a negotiated peace based on humanistic principles. Turning ‘Spears into Ploughshares’ is a long gestation project but the warring sides should pay considerable attention to former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s memorable thesis that the world needs to transition from a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ to a ‘Dialogue of Civilizations’. Hopefully, there would emerge from the main divides leaders who could courageously take up the latter challenge.

It ought to be plain to see that the current regional war in the Middle East is jeopardising the best interests of the totality of publics. Those Americans who are for peace need to not only stand up and be counted but bring pressure on the Trump administration to make peace and not continue on the present destructive course that will render the world a far more dangerous place than it is now.

In the Middle East region a durable peace could be ushered if only the just needs of all sides to the conflict are constructively considered. The Palestinians and Arabs have their needs, so does Israel. It cannot be stressed enough that unless and until the security needs of the latter are met there could be no enduring peace in the Middle East.

Features

The art and science of communicating with your little child

The two input gateways of communication, sight and sound, are quite well developed at birth. In fact, the auditory system becomes functional around 24 weeks in the womb, and the normal newborn can hear quite well after birth. However, the newborn’s vision is a little blurry at birth, and the baby sees the world in shades of grey, while being able only to focus on things 20 to 30 cm (8–12 inches) away. Coincidentally, this is perhaps the exact distance to a mother’s face during breastfeeding. By 2-3 months, there are colour vision capabilities and the ability to track. By 5-8 months, there is depth perception, and by 12 months, there is adult clarity of vision.

By the time a child turns five, his or her brain has already reached 90% of its adult size. This astonishing physical growth is not just happening on its own; it is, to a certain extent, fuelled by experience, and the most vital experience a young child can have is communication with his or her parents.

Modern developmental neuroscience has shifted our understanding of how children learn. We used to think babies were passive sponges, slowly absorbing the world. We now know they are active characters from day one, constantly seeking interaction to build the architecture of their minds. This architecture is not built by apps, vocabulary flashcards, or educational television. It is built through simple, loving, back-and-forth interactions with anyone they come across, but mostly their parents.

The Foundation: Serve and Return (0–12 Months)

Communication with an infant from birth to one year of age begins long before they speak their first word. In the first year, the goal is to master a phenomenon called Serve and Return. This is a basic scenario picked up from the game of tennis. At the start of each game of a set in tennis, a player serves, and the opponent returns the serve. Just imagine a tennis match, where a baby “serves” by making a sound, making eye contact, reaching for a toy, or crying. The job of anyone in the vicinity, who very often are the parents of the baby, is to “return” the ball. If they babble, you babble back. If they point at a cat, you look and say, “Yes, that’s a furry cat!” This simple act does two things. The first is Brain Building, which creates and strengthens neural pathways in the language and emotional centres of the brain. The other is Emotional Security, a thing which teaches a baby that he or she has some help in the learning processes. The baby absorbs the notion that when he or she signals a need, his or her world will respond. This forms the basis of a secure attachment. Scientists have advocated that during this stage, people, especially the parents of a baby, should embrace what is called ‘parentese’. It is the use of a somewhat high-pitched, exaggerated voice. Research has shown that babies pay more attention to parentese than to regular adult speech, helping them to map the sounds of their native language more quickly.

The Language Explosion: Toddlers (1–3 Years)

When a child starts speaking words, the game changes considerably and quite profoundly. This period is defined by a rapid increase in his or her vocabulary and the beginning of grammar. It is very important to narrate everything. The people around, especially the parents, need to become kind of sports commentators for your life. While dressing them, one could say, “First we put on the red sock. After that, we put the other red sock on your left foot.” What we are doing by this is to give them the labels for the world they see.

It is also important to expand, but not truly correct, whatever the child says. If a toddler points to a car and says “Car!”, don’t just say “Yes.” Expand on it: “Yes, that is a big, fast, red car!” You are adding a new vocabulary and grammatical structure through a natural process. If the child says “Me go,” respond with, “Yes, you are going!” rather than correcting and saying “No…, you should say ‘I am going’.”

Toddlers love reading the same book, even one hundred times. While it may be tedious for those around the baby, it is important to realise that such repetition is vital for their learning. They are predicting what comes next, which is a core cognitive skill.

The Preschooler: Building Stories and Logic (3–5 Years)

By age three, the focus shifts from “what” to “why.” Preschoolers are beginning to understand complex emotions, time, and causality. This is the age at which it is best to ask questions which require thought and understanding. Such indirect open-ended questions would sound like “What was the best part of the park today?” or “How do you think that character in the story is feeling?“

A preschooler’s world is full of “big feelings” they cannot yet manage. When they are upset because they cannot have a cookie, avoid saying “Don’t cry over nothing.” Instead, name the emotion: “Don’t cry, you can have a cookie after dinner“. This teaches them emotional literacy. Parents and others around in the home could share stories about when they were little, or make up fantasy tales together. Storytelling teaches sequential logic (beginning, middle, end) and strengthens their imagination.

The Absolute Master Class: Learning Through Play

If communication is the fuel for brain development, play is the engine. For a child under five, play is not a break from learning; play is learning. It is how they explore physics (stacking blocks), mathematics (sorting shapes), social dynamics (sharing toys), and language (pretend play). We can boost their development exponentially by weaving communication into their play.

When a child is playing with blocks, dough, or puzzles, they are building fine motor skills and spatial awareness. It is also useful to use three-dimensional words: “Can you put the blue block on top of the red one?” “The puzzle piece is next to your knee.” One could also ask them to describe the texture: “Is the dough soft or hard?“

Pretend play, such as acting as a doctor, an engineer, a chef, or a superhero, is one of the most cognitively demanding things a child can do. It requires them to understand symbolic thought and to take on another person’s perspective. Join their world as a supporting character, not the director. If they are the doctor, ask, “Doctor, my teddy bear’s tummy hurts. What should I do?” This encourages them to use vocabulary relevant to the scenario and practice complex social problem-solving.

Playing with water, sand, slime, or safe food products allows children to process sensory information. This is the perfect time for descriptive vocabulary. Use contrasting words: wet/dry, hot/cold, sticky/smooth, loud/quiet.

A few special words for parents. You do not need an expensive degree or specialised toys to build your child’s brain. The most powerful tool you have is your own responsiveness. Modern science tells us that the basic recipe for a thriving child is simple: Look at them when they signal you. Respond with warmth and words. Narrate their world and Join their play.

You are not just talking to your child; you are building his or her future, even via just one conversation at a time. So, go on talking to your child and even make him or her a real-life chatterbox.

Dr B. J. C. Perera

Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Features

Promoting our beauty and culture to the world

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

With this in mind, Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency recently had a spectacular event to select Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka in order to promote Sri Lanka in the international scene.

Nimesha Premachandra was crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026.

She says she owes her success to Ruki (Rukmal Senanayake), the National Director and model trainer, and personality and advocacy trainer Tharaka Gurukanda.

Nimesha is a school teacher by profession, an actress and TV presenter by passion, and an entrepreneur by spirit.

She believes in balancing grace with purpose, and using her platform to inspire women, while promoting the beauty and culture of Sri Lanka to the world. And this is how our Chit-Chat went:

Nimesha Premachandra: Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026

01. How would you describe yourself?

I am a passionate, disciplined, and people-oriented person. I love learning, performing, and guiding others, especially young minds, through education.

02. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

I would probably try to be less self-critical and allow myself to celebrate achievements more often.

03. If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

Nothing major. I am grateful for my family’s love and support, which has shaped who I am today.

04. Is Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka your very first pageant?

No. I have been part of pageants before, but Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka is very special because it represents purpose, culture, and global representation.

05. What made you take part in this contest?

I wanted to represent Sri Lanka internationally and use this platform to promote tourism, culture, and women’s empowerment.

06. Obviously, you must be excited about participating in the grand finale, in Vietnam; any special plans for this big event?

Yes, I am extremely excited. My focus is to showcase Sri Lankan elegance, hospitality, and authenticity, while building meaningful connections with participants from around the world.

07. How do you intend promoting tourism, in Sri Lanka, during your rein?

I plan to highlight Sri Lanka’s diverse experiences in culture, heritage, wellness, nature, and local hospitality through media appearances, digital storytelling, and tourism collaborations.

08. School?

Kaluthara Balika. School life played a big role in shaping me. I actively participated in sports and performing arts, which later helped me build confidence as an actress and presenter.

09. Happiest moment?

Being crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026 and seeing the pride in my family’s eyes – definitely one of my happiest moments.

10. What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Peace of mind, good health, and being surrounded by the people I love while doing work that has meaning.

11. Which living person do you most admire?

I most admire Angelina Jolie because she beautifully balances her work as an actress with meaningful humanitarian efforts. She uses her global platform to support refugees, advocate for human rights, and inspire women to be strong, compassionate, and independent.

12. Which is your most treasured possession?

My memories and experiences because they remind me how far I’ve come, and keep me grounded.

13. Your most embarrassing moment?

Like everyone, I’ve had small on-stage mishaps, but they always taught me to laugh at myself and move forward confidently.

14. Done anything daring?

Participating in pageants while balancing teaching, media work, and family life has been one of the boldest and most rewarding decisions I’ve made.

Keen to use her title to promote Sri Lanka globally

15. Your ideal vacation?

A peaceful destination surrounded by nature; somewhere I can relax, reconnect, and experience local culture.

16. What kind of music are you into?

I enjoy soft, soulful music because it helps me relax and stay inspired.

17. Favourite radio station:

I enjoy stations that blend good music with meaningful conversation and positive energy.

18. Favourite TV station:

Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation. It’s where it all began for me. It played a significant role in my journey as a TV presenter and helped shape my confidence and passion for media.

19 What would you like to be born as in your next life?

Someone who continues to inspire others because making a positive impact is what matters most.

20. Any major plans for the future?

I hope to expand my work in media and entrepreneurship while continuing my role as an educator and using my title to promote Sri Lanka globally.

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

-

Features3 days ago

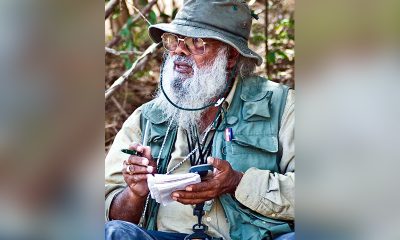

Features3 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul