Features

Sri Lanka under British rule : Neither Gemeinschaft nor Gesellschaft

By Uditha Devapriya

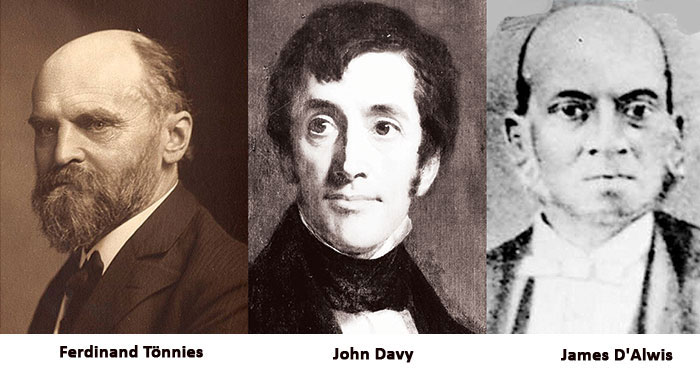

Since at least Marx and Malinowski, anthropologists have been fascinated by, and focused on, the links between “primitive-tribal” and “modern-secular” societies. I use these terms with a pinch of salt – hence the asterisks – for the simple reason that no society can be said to fit one case or the other. In its initial phase the social sciences did, admittedly, distinguish between the two, and took the teleological position that the one would lead to another: hence Ferdinand Tönnies’s idea of a progression from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft. Such progressions were depicted as long, eventual, but inevitable, and were accepted widely at a time when Europe, the harbinger of industrialisation and colonialism, had consolidated its position as the main, if not sole, locomotive of world history.

I have pointed out earlier, in this column, that Europe’s encounters with the non-West – Africa and Asia, basically – did not spur the kind of transition from tribalism to modernity which the most benighted missionary and colonial official had publicly advocated. This was no less true in India than it was in Sri Lanka. To give a simple and much used example, upon their annexation of Kandy, the colonial government did not do away with the caste-based duty system, and corvee labour, at once. Unlike scholars and romantics who envisioned a supposedly nobler role for the colonising West, the administrators and officials working on the ground saw the need to retain precapitalist, and thus primitive, social relations, in order to legitimise their rule over the newly acquired territories.

One discerns an intriguing, if fundamental, disconnect or contradiction here, between the supposed aims and the actual, lived experience of colonial rule. If the objective of colonial rule was indeed to transform the societies they had acquired by force and compulsion, then the relationship between the coloniser and colonised had to go beyond the position of mere dependence which colonised territories were subjected to. We know, however, that this was never the case. India, for instance, accounted for a quarter of the world’s industrial production, and British rule smothered its textile sector in the interests of ensuring a market for British textile exports. What this reveals is that, regardless of what scholars at the time may have believed, the West was primarily interested in sabotaging the national industries of the non-West, rather than in transforming their societies.

It was the destruction of these industries, as well as official patronage of precapitalist social relations, especially in regions like Kandy, that hindered the long progression from tribalism to modernity which the likes of Tönnies, Durkheim, and Henry Maine advocated. The latter were, strictly speaking, not propagandists or mouthpieces for colonialism: it would be wrong to consider them so on the basis of their Western and European background alone. But they were products of their time, and in their time the Western view of non-Western countries gradually being subsumed by colonialism and then developing into capitalist and modernist societies was more or less accepted. Even Marx, in his initial despatches on India, pondered whether British colonialism would beneficially impact that country’s historical and economic trajectory. Of course, Marx later changed his position, proving himself an exception.

In any case, these processes ran their course more discernibly, and thoroughly, in Sri Lanka than they did in India, where, perhaps because of its size or its plurality, colonial rule did not, and could not, destroy its industrial base or pre-empt the formation of an industrial (and somewhat anti-imperialist) bourgeoisie. In Sri Lanka, by contrast, British rule managed successfully to hinder the progression from feudalism to capitalism, thereby preventing it from achieving a transition from “tribalism” to “modernity.”

Since I have reflected on these concerns in my recent essay on Maduwanwela Dissawe and the temples of the South, I will limit my analysis here to another area where colonial rule had an undeniably distinct, and paradoxical, impact on local society.

Education had long been viewed, even by the Portuguese, and more prominently by the Dutch, as a useful instrument for the consolidation of colonial power. The Dutch, through their network of parish schools, were interested more in eradicating Portuguese power – with little to no effect, as the enduring popularity of Catholicism, even today, illustrates – than in educating local elites. The latter objective formed the cornerstone of British policy on education, particularly after the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1833.

The British government was itself not in one mind over education, and it was hardly in agreement with missionary enclaves who were interested more in converting locals to their specific brand or denomination. But by and large, a sort of tacit understanding developed between the two that these schools would inculcate Western values, and educate a class of locals who could staff the civil administrative service.

The first British officials to set foot in Kandy – among them, John Davy – were demonstrably surprised at the state of education there. Products of elite public schools and universities themselves, they were astonished by how much of a widespread institution education had become in the highlands, administered by the pansalas and limited to the male population. In Britain at the time, education had become the preserve of the old aristocracy and an emerging bourgeoisie. It was this model, based fundamentally on filtration theory – or the entrenchment of a minority, to the exclusion of the masses – which British officials sought to enforce in the island. By contrast, missionary bodies were interested in taking their gospel as far as possible, even preaching it in the vernacular. Yet even though they were in conflict with the government’s more utilitarian approach to education, over the years they conformed to that approach while pursuing their own objectives.

For obvious and logical reasons, the institutions of a colonial society – the superstructure, to borrow Marxist terminology – acutely reflect, or appropriate, that society’s economic base. In Sri Lanka, colonialism had transformed if not transmogrified precapitalist social relations without fundamentally challenging them: hence the government’s decision to retain rather than overhaul caste and rajakariya, and hence its decision to co-opt rather than eradicate the Kandyan aristocracy. Within such a setup, a transition from tribalism to modernity was simply not possible, particularly after the grafting of a plantation economy which reduced the peasantry to a position of dependence while undercutting them through the import of cheap, indentured, and perpetually exploited labour from South India.

It goes without saying that this setup was well reflected in the schools and other educational institutions that the colonial State established in the mid-19th century. How so? First and foremost, these schools reaffirmed the colonial State’s advocacy, and enforcement, of elite filtration, or education for a minority as opposed to the masses. In areas like Kandy, the State did not interfere when missionary bodies set up schools, because it provided them with the opportunity to educate the children of native elites and European planters. The colonial State itself did not own the kind of “superior” schools that missionary bodies did: it had the Colombo Academy, but that was in Colombo. Elsewhere, as far as the aims of the State and missionary enclaves went, laissez-faire ruled the day. Individual governors may have held views that were antithetical to the aims of these enclaves, but again, such rifts were temporary, and were in any case resolved by succeeding governors.

Secondly, the curriculum of these schools was, in comparison to the needs of a society that had yet not industrialised, hardly modern or progressive. The students of these institutions not only learnt the literature, history, and culture of a society far removed from them, their very education distanced them from the society to which they had been born. This had the dual effect of distancing themselves from their roots while failing to root them in the society of the “mother country”, or the metropole. James d’Alwis’s memoirs, in which he recounts the pressure to conform and uproot himself that he experienced at the Colombo Academy, illustrate this dilemma well. Many years later, Ralph Pieris could recount his childhood at the Academy – by then renamed Royal College – in just about the same terms. I quote him in full, simply because it sheds light on what these schools stood for.

“The Ceylon schools supported an authoritarian regime in the classroom where the rod was not spared, idealised ‘manly’ sports such as boxing and rugger, while a disciplined military apprenticeship was provided by the cadet battalion. Many adults have hankering fixation on school life, the joys of cricket; and masochistic adoration or the father-figures of teachers. even if they were responsible for sadistic and humiliating physical chastisement… All too frequently I have witnessed the tragicomic spectacle of elderly men leading a hollow existence, pitiful spectators of sports they can no longer actively participate in, who have rejoiced only in the transient marvel of their physical strength, [to] discover in later life that their range has become restricted and their interests few.”

Ralph Pieris, Sociology as a Calling: A Desultory Memoir

Modern Sri Lanka Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1988, pp 1-33

Pieris’s observation leads me to my third point, which is that the elitism engendered and perpetuated by these institutions continued long after colonial rule, and in fact continues today. There are, of course, important differences between colonial and post-colonial society. The right to vote, and free education, emancipated the masses from the fields or “avocations” to which the colonial State had restricted them. These developments were not wholeheartedly accepted by the elite of the day: in criticising the Central School System, for instance, a member of the Colombo upper class remarked that the new schools would never be as good as the elite ones. Yet such reforms had in themselves been necessitated by the right to vote, and could not be prevented or pre-empted. Despite the machinations of the English-speaking bourgeoisie – which either accepted these reforms or chose to migrate from the country – free education became well established, even in the schools which they had attended, and to which many of them continued sending their sons.

In my essay on the Royal College Hostel, published last August, I noted that independence brought about a transfer of power from the legatees of British power to an indigenous class. In elite schools, I added, this transfer was not so much from the upper echelons to the lower classes as it was from an elite to an upward aspiring petty bourgeoisie, or intermediate elite. Such transformations did not fundamentally put to question, much less challenge, the elitist structures that had been implanted in these establishments by the British government. This is why Pieris’s memoirs paint an accurate picture of these institutions, not just from his time but also from ours: Pieris’s description of past pupils’ “hankering fixation on school life, the joys of cricket” and of “elderly men leading a hollow existence, pitiful spectators or sports they can no longer actively participate in”, to give one example, is amply visible at the many matches, parades, and functions organised by these schools today.

All this goes back to my original point, that British rule did not liberate colonial societies, like ours, from our tribalist past. A careful examination of the institutions which were set up by colonial officials here, during that period, should make that much clear. The transition from colonial to post-colonial society has not really challenged the status quo. If at all, it has only substituted the domination of one social class for that of another: the petty bourgeoisie, for the Anglicised colonial elite. Against such a backdrop, it behoves us to ask what exactly must be done to ensure, not merely the eradication of colonial-precapitalist remnants in these institutions, but the eventual progression, in our country, from the colonial-tribalist setup to which it continues to be tethered, 75 years after independence, to a truly modern, secular, and progressive society. Such a transformation requires a radical shift in our perceptions of education, governance, and political reform. Yet it is needed, especially at a time when mass anger against the elite class has reached fever pitch.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Educational reforms under the NPP government

When the National People’s Power won elections in 2024, there was much hope that the country’s education sector could be made better. Besides the promise of good governance and system change that the NPP offered, this hope was fuelled in part by the appointment of an academic who was at the forefront of the struggle to strengthen free public education and actively involved in the campaign for 6% of GDP for education, as the Minister of Education.

When the National People’s Power won elections in 2024, there was much hope that the country’s education sector could be made better. Besides the promise of good governance and system change that the NPP offered, this hope was fuelled in part by the appointment of an academic who was at the forefront of the struggle to strengthen free public education and actively involved in the campaign for 6% of GDP for education, as the Minister of Education.

Reforms in the education sector are underway including, a key encouraging move to mainstream vocational education as part of the school curriculum. There has been a marginal increase in budgetary allocations for education. New infrastructure facilities are to be introduced at some universities. The freeze on recruitment is slowly being lifted. However, there is much to be desired in the government’s performance for the past one year. Basic democratic values like rule of law, transparency and consultation, let alone far-reaching systemic changes, such as allocation of more funds for education, combating the neoliberal push towards privatisation and eradication of resource inequalities within the public university system, are not given due importance in the current approach to educational and institutional reforms. This edition of Kuppi Talk focuses on the general educational reforms and the institutional reforms required in the public university system.

General Educational Reforms

Any reform process – whether it is in education or any other area – needs to be shaped by public opinion. A country’s education sector should take into serious consideration the views of students, parents, teachers, educational administrators, associated unions, and the wider public in formulating the reforms. Especially after Aragalaya/Porattam, the country saw a significant political shift. Disillusionment with the traditional political elite mired in corruption, nepotism, racism and self-serving agendas, brought the NPP to power. In such a context, the expectation that any reforms should connect with the people, especially communities that have been systematically excluded from processes of policymaking and governance, is high.

Sadly, the general educational reforms, which are being implemented this year, emerged without much discussion on what recent political changes meant to the people and the education sector. Many felt that the new government should not have been hasty in introducing these reforms in 2026. The present state of affairs calls for self-introspection. As members affiliated to the National Institute of Education (NIE), we must acknowledge that we should have collectively insisted on more time for consultation, deliberations and review.

The government’s conflicts with the teachers’ unions over the extension of school hours, the History teachers’ opposition to the removal of History from the list of compulsory exam subjects for Grades 10 and 11, the discontent with regard to the increase in the number of subjects (now presented as modules) for Grade 6 classes could have been avoided, had there been adequate time spent on consultations.

Given the opposition to the current set of reforms, the government should keep engaging all concerned actors on changes that could be brought about in the coming years. Instead of adopting an intransigent position or ignoring mistakes made, the government and we, the members affiliated to NIE, need to keep the reform process alive, remain open to critique, and treat the latest policy framework, the exams and evaluation methods, and even the modules, as live documents that can be made better, based on constructive feedback and public opinion.

Philosophy and Content

As Ramya Kumar observed in the last edition of Kuppi Talk, there are many refreshing ideas included in the educational philosophy that appears in the latest version of the policy document on educational reforms. But, sadly, it was not possible for curriculum writers to reflect on how this policy could inform the actual content as many of the modules had been sent for printing even before the policy was released to the public. An extensive public discussion of the proposed educational vision would have helped those involved in designing the curriculum to prioritise subjects and disciplines that need to be given importance in a country that went through a protracted civil war and continue to face deep ethno-religious divisions.

While I appreciate the statement made by the Minister of Education, in Parliament, that the histories of minority communities will be included in the new curriculum, a wider public discussion might have pushed the government and NIE to allocate more time for subjects like the Second National Language and include History or a Social Science subject under the list of compulsory subjects. Now that a detailed policy document is in the public domain, there should be a serious conversation about how best the progressive aspects of its philosophy could be made to inform the actual content of the curriculum, its implementation and pedagogy in the future.

University Reforms

Another reform process where the government seems to be going headfirst is the amendments to the Universities Act. While laws need to be revisited and changes be made where required, the existent law should govern the way things are done until a new law comes into place. Recently, a circular was issued by the University Grants Commission (UGC) to halt the process of appointing Heads of Departments and Deans until the proposed amendments to the University Act come into effect. Such an intervention by the UGC is totalitarian and undermines the academic and institutional culture within the public university system and goes against the principle of rule of law.

There have been longstanding demands with regard to institutional reforms such as a transparent process in appointing council members to the public university system, reforms in the schemes of recruitment and selection processes for Vice Chancellor and academics, and the withdrawal of the circular banning teachers of law from practising, to name a few.

The need for a system where the evaluation of applicants for the post of Vice Chancellor cannot be manipulated by the Council members is strongly felt today, given the way some candidates have reportedly been marked up/down in an unfair manner for subjective criteria (e.g., leadership, integrity) in recent selection processes. Likewise, academic recruitment sometimes penalises scholars with inter-disciplinary backgrounds and compartmentalises knowledge within hermetically sealed boundaries. Rigid disciplinary specificities and ambiguities around terms such as ‘subject’ and ‘field’ in the recruitment scheme have been used to reject applicants with outstanding publications by those within the system who saw them as a threat to their positions. The government should work towards reforms in these areas, too, but through adequate deliberations and dialogue.

From Mindless Efficiency to Patient Deliberations

Given the seeming lack of interest on the part of the government to listen to public opinion, in 2026, academics, trade unions and students should be more active in their struggle for transparency and consultations. This struggle has to happen alongside our ongoing struggles for higher allocations for education, better infrastructure, increased recruitment and better work environment. Part of this struggle involves holding the NPP government, UGC, NIE, our universities and schools accountable.

The new year requires us to think about social justice and accountability in education in new ways, also in the light of the Ditwah catastrophe. The decision to cancel the third-term exams, delegating the authority to decide when to re-open affected schools to local educational bodies and Principals and not change the school hours in view of the difficulties caused by Ditwah are commendable moves. But there is much more that we have to do both in addressing the practical needs of the people affected by Ditwah and understanding the implications of this crisis to our framing of education as social justice.

To what extent is our educational policymaking aware of the special concerns of students, teachers and schools affected by Ditwah and other similar catastrophes? Do the authorities know enough about what these students, teachers and institutions expect via educational and institutional reforms? What steps have we taken to find out their priorities and their understanding of educational reforms at this critical juncture? What steps did we take in the past to consult communities that are prone to climate disasters? We should not shy away from decelerating the reform process, if that is what the present moment of climate crisis exacerbated by historical inequalities of class, gender, ethnicity and region in areas like Malaiyaham requires, especially in a situation where deliberations have been found lacking.

This piece calls for slowing-down as a counter practice, a decelerating move against mindless efficiency and speed demanded by neoliberal donor agencies during reform processes at the risk of public opinion, especially of those on the margins. Such framing can help us see openness, patience, accountability, humility and the will to self-introspect and self-correct as our guides in envisioning and implementing educational reforms in the new year and beyond.

(Mahendran Thiruvarangan is a Senior Lecturer attached to the Department of Linguistics & English at the University of Jaffna)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies

by Mahendran Thiruvarangan

Features

Build trust through inclusion and consultation in the New Year

Looking back at the past year, the anxiety among influential sections of the population that the NPP government would destabilise the country has been dispelled. There was concern that the new government with its strong JVP leadership might not be respectful of private property in the Marxist tradition. These fears have not materialised. The government has made a smooth transition, with no upheavals and no breakdown of governance. This continuity deserves recognition. In general, smooth political transitions following decisive electoral change may be identified as early indicators of democratic consolidation rather than disruption.

Democratic legitimacy is strengthened when new governments respect inherited institutions rather than seek to dismantle them wholesale. On this score, the government’s first year has been positive. However, the challenges that the government faces are many. The government’s failure to appoint an Auditor General, coupled with its determination to push through nominees of its own choosing without accommodating objections from the opposition and civil society, reflects a deeper problem. The government’s position is that the Constitutional Council is making biased decisions when it rejects the president’s nominations to the position of Auditor General.

Many if not most of the government’s appointments to high positions of state have been drawn from a narrow base of ruling party members and associates. The government’s core entity, the JVP, has had a traditional voter base of no more than 5 percent. Limiting selection of top officials to its members or associates is a recipe for not getting the best. It leaves out a wide swathe of competent persons which is counterproductive to the national interest. Reliance on a narrow pool of party affiliated individuals for senior state appointments limits access to talent and expertise, though the government may have its own reasons.

The recent furor arising out of the Grade 6 children’s textbook having a weblink to a gay dating site appears to be an act of sabotage. Prime Minister (and Education Minister Harini Amarasuriya) has been unfairly and unreasonably targeted for attack by her political opponents. Governments that professionalise the civil service rather than politicise them have been more successful in sustaining reform in the longer term in keeping with the national interest. In Sri Lanka, officers of the state are not allowed to contest elections while in service (Establishment Code) which indicates that they cannot be linked to any party as they have to serve all.

Skilled Leadership

The government is also being subjected to criticism by the Opposition for promising much in its election manifesto and failing to deliver on those promises. In this regard, the NPP has been no different to the other political parties that contested those elections making extravagant promises. The problem is that the economic collapse of 2022 set the country back several years in terms of income and living standards. The economy regressed to the levels of 2018, which was not due to actions of the NPP. Even the most skilled leadership today cannot simply erase those lost years. The economy rebounded to around five percent growth in the past year, but this recovery now faces new problems following Cyclone Ditwah, which wiped out an estimated ten percent of national income.

In the aftermath of the cyclone, the country’s cause for shame lies with the political parties. Rather than coming together to support relief and recovery, many focused on assigning blame and scoring political points, as in the attacks on the prime minister, undermining public confidence in the state apparatus at a moment when trust was essential. Despite the politically motivated attacks by some, the government needs to stick to the path of inclusiveness in its approach to governance. The sustainability of policy change depends not only on electoral victory but on inclusive processes that are more likely to endure than those imposed by majorities.

Bipartisanship recognises that national rebuilding and reconciliation requires cooperation across political divides. It requires consultation with the opposition and with civil society. Opposition leader Sajith Premadasa has been generally reasonable and constructive in his approach. A broader view of bipartisanship is that it needs to extend beyond the mainstream opposition to include ethnic and religious minorities. The government’s commitment to equal rights and non-discrimination has had a positive impact. Visible racism has declined, and minorities report feeling physically safer than in the past. These gains should not be underestimated. However, deeper threats to ethnic harmony remain.

The government needs to do more to make national reconciliation practical and rooted in change on the ground rather than symbolic. Political power sharing is central to this task. Minority communities, particularly in the north and east, continue to feel excluded from national development. While they welcome visits and dialogue with national leaders, frustration grows when development promises remain confined to foundation stones and ceremonies. The construction of Buddhist temples in areas with no Buddhist population, justified on claims of historical precedent, is perceived as threatening rather than reconciliatory.

Wider Polity

The constitutionally mandated devolution framework provided by the Thirteenth Amendment remains the most viable mechanism for addressing minority grievances within a united country. It was mediated by India as a third party to the agreement. The long delayed provincial council elections need to be held without further postponement. Provincial council elections have not been held for seven years. This prolonged suspension undermines both democratic practice and minority confidence. International experience, whether in India and Switzerland, shows that decentralisation is most effective when regional institutions are electorally accountable and operational rather than dormant.

It is not sufficient to treat individuals as equal citizens in the abstract. Democratic equality also requires recognising communities as collective actors with legitimate interests. Power sharing allows communities to make decisions in areas where they form majorities, reducing alienation and strengthening national cohesion. The government’s first year in office saw it acknowledge many of these problems, but acknowledgment has not yet translated into action. Issues relating to missing persons, prolonged detention, land encroachment and the absence of provincial elections remain unresolved. Even in areas where reform has been attempted, such as the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the proposed replacement legislation falls short of international human rights standards.

The New Year must be one in which these foundational issues are addressed decisively. If not, problems will fester, get worse and distract the government from engaging fully in the development process. Devolution through the Thirteenth Amendment and credible reconciliation mechanisms must move from rhetoric to implementation. It is reported that a resolution to appoint a select committee of parliament to look into and report on an electoral system under which the provincial council elections will be held will be taken up this week. Similarly, existing institutions such as the Office of Missing Persons and the Office of Reparations need to be empowered to function effectively, while a truth and reconciliation process must be established that commands public confidence.

Trust in institutions requires respect for constitutional processes, trust in society requires inclusive decision making, and trust across communities requires genuine power sharing and accountability. Economic recovery, disaster reconstruction, institutional integrity and ethnic reconciliation are not separate tasks but interlinked tests of democratic governance. The government needs to move beyond reliance on its core supporters and govern in a manner that draws in the wider polity. Its success here will determine not only the sustainability of its reforms but also the country’s prospects for long term stability and unity.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Not taking responsibility, lack of accountability

While agreeing wholeheartedly with most of the sentiments expressed by Dr Geewananda Gunawardhana in his piece “Pharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics” (The Island, 5th January), I must take exception to what he stated regarding corruption: “Enough has been said about corruption, and fortunately, the present government is making an effort to curb it. We must give them some time as only the government has changed, not the people”

With every change of government, we have witnessed the scenario of the incoming government going after the corrupt of the previous, punishing a few politicians in the process. This is nothing new. In fact, some governments have gone after high-ranking public servants, too, punishing them on very flimsy grounds. One of the main reasons, if not the main, of the unexpected massive victory at the polls of this government was the promise of eradication of corruption. Whilst claiming credit for convicting some errant politicians, even for cases that commenced before they came to power, how has the NPP government fared? If one considers corruption to be purely financial, then they have done well, so far. Well, even with previous governments they did not commence plundering the wealth of the nation in the first year!

I would argue that dishonesty, even refusal to take responsibility is corruption. Plucking out of retirement and giving plum jobs to those who canvassed key groups, in my opinion, is even worse corruption than some financial malpractices. There is no need to go into the details of Ranwala affairs as much has been written about but the way the government responded does not reassure anyone expecting and hoping for the NPP government to be corruption free.

One of the first important actions of the government was the election of Ranwala as the speaker. When his claimed doctorate was queried and he stepped down to find the certificate, why didn’t AKD give him a time limit to find it? When he could not substantiate obtaining a PhD, even after a year, why didn’t AKD insist that he resigns the parliamentary seat? Had such actions been taken then the NPP can claim credit that the party does not tolerate dishonesty. What an example are we setting for the youth?

Recent road traffic accident involving Ranwala brough to focus this lapse too, in addition to the laughable way the RTA was handled. The police officers investigating could not breathalyse him as they had run out of ‘balloons’ for the breathalyser! His blood and urine alcohol levels were done only after a safe period had elapsed. Not surprisingly, the results were normal! Honestly, does the government believe that anyone with an iota of intelligence would accept the explanation that these were lapses on the part of the police but not due to political interference?

The release of over 300 ‘red-tagged’ containers continues to remain a mystery. The deputy minister of shipping announced loudly that the ministry would take full responsibility but subsequently it turned out that customs is not under the purview of the ministry of shipping. Report on the affair is yet to see the light of day, the only thing that happened being the senior officer in customs that defended the government’s action being appointed the chief! Are these the actions of a government that came to power on the promise of eradication of corruption?

The new year dawned with another headache for the government that promised ‘system change.’ The most important educational reforms in our political history were those introduced by Dr CWW Kannangara which included free education and the establishment of central schools, etc. He did so after a comprehensive study lasting over six years, but the NPP government has been in a rush! Against the advice of many educationists that reforms should be brought after consultation, the government decided it could rush it on its own. It refuses to take responsibility when things go wrong. Heavens, things have started going wrong even before it started! Grade Six English Language module textbook gives a link to make e-buddies. When I clicked that link what I got was a site that stated: “Buddy, Bad Boys Club, Meet Gay Men for fun”!

Australia has already banned social media to children under 15 years and a recent survey showed that nearly two thirds of parents in the UK also favour such a ban but our minister of education wants children as young as ten years to join social media and have e-buddies!

Coming back to the aforesaid website, instead of an internal investigation to find out what went wrong, the Secretary to the Ministry of Education went to the CID. Of course, who is there in the CID? Shani of Ranjan Ramanayake tape fame! He will surely ‘fix’ someone for ‘sabotaging’ educational reforms! Can we say that the NPP government is less corrupt and any better than its predecessors?

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoPharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoCurran, bowlers lead Desert Vipers to maiden ILT20 title