Features

Sri Lanka sails into murky waters in the Red Sea

By Uditha Devapriya

Speaking at an awards ceremony on Wednesday, January 3, President Ranil Wickremesinghe announced that the government would be deploying a Navy vessel to the Red Sea. Wickremesinghe pointed out that the disruption of shipping lanes in the region would lead to increased freight charges and cargo costs, increasing import prices in the country. Arguing that this was not in Sri Lanka’s interest, he declared that the government would do what it could to contribute to stability in the region.

The announcement came as a surprise to many, not least since the President revealed it only towards the tail-end of his speech. Soon after, the government launched a feasibility study for the proposal. The President had earlier admitted that deploying a vessel would cost the government Rs 250 million every fortnight, while a Navy spokesman stated that the Red Sea operation required clear “logistics supplies” and “a robust weapon outfit.” Meanwhile, on social media and in the press, commentators and analysts weighed in on the proposal, many expressing scepticism at and condemning the move.

The Sri Lanka Navy has since confirmed that it will be despatching a number of vessels to the region. While no date has been finalised yet, the Navy has stated that the deployment will be in support of Operation Prosperity Guardian, the United States led initiative combating Houthi rebels in the Red Sea. The rebels have vowed not to back down until Israel ends its attacks on Palestine. Since December, they have planned and carried out a series of drone and missile strikes which have forced cargo ships to reroute. In response, several countries, including India, have deployed vessels to the region.

Sri Lanka is the latest country to join these efforts, but its entry seems to have left more questions than answers. For one thing, the Red Sea operation marks the first major military confrontation between the US and the Houthi rebels. This has several crucial geopolitical implications.

On the one hand, the US and its allies have justified their intervention on the grounds of protecting international trade and shipping lines, while the Houthis have justified their attacks as a show of solidarity with Palestine and Gaza. On the other, the rebels are allegedly backed by Iran, which has so far belittled or ignored US warnings, and has gone so far as to deploy a warship in response to escalating tensions.

Complicating matters further, US allies themselves seem less than forthcoming about their involvement. When Washington launched Operation Prosperity Guardian in December, the Pentagon announced a united campaign of several countries, many from Europe. Yet apart from a few like the UK, most of them have kept their participation under wraps. The more forthcoming among them have made relatively modest contributions, while key allies such as Germany have been ambivalent about the extent of their intervention.

On the face of it, Europe’s indecisiveness has left an opening for US allies in other regions to assert their strength in the Red Sea operation. India, for instance, has despatched escorts, including frigates and destroyers, for Indian container ships.

The United States has invited Delhi to join its coalition, the Combined Maritime Forces, expanding its reach in the Red Sea as well as in adjacent regions. Yet while India has been willing to commission vessels to the Red Sea, it has preferred to maintain its own presence rather than joining a coalition. As of now, tellingly, no Asian country apart from Bahrain – the sole Gulf country to join – has deployed vessels for the operation; Singapore and Seychelles have agreed to take part, but only to contribute to information sharing.

Sri Lanka’s willingness to join with US forces is hence perplexing. Ostensibly, it is filling a gap no other Asian country has: in December, it became the 39th country to join the Combined Maritime Forces partnership. While details of the vessels that will be despatched to the Red Sea have yet to be confirmed, reports indicate they will be stationed outside the immediate Houthi weapons range, given the near absence of air defence and counter-missile systems in Sri Lankan Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs). When these vessels enter the Red Sea, they will be placed under the command of US Task Force 153.

Yet, however perplexing these developments may be, they are hardly unpredictable. The Sri Lankan and the US Navies have been engaging and cooperating with each other for a fairly long time. Last year, for instance, they embarked on a series of training sessions to prepare for disaster relief and “maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific.” These exercises and sessions will be conducted this year as well.

The US Navy has also handed over ships and coastguard cutters to the Sri Lankan Navy. In fact, two of the three ships which have been proposed for the Red Sea operation, SLNS Gajabahu and SLNS Vijayabahu, were gifted by the US in 2018 and 2021 respectively. Given these engagements, the Sri Lankan Navy’s willingness to deploy ships to the Red Sea under the US Fleet’s command is not entirely surprising.

There are arguments for and against the proposal on both the domestic and foreign policy front. On the domestic front, perhaps the biggest concern is cost. The operation is expected to burn up LKR 250 million or USD 777,000 every two weeks. The government has justified the expense on the basis that securing the Red Sea would help stabilise import prices. On the face of it, this is true. Marine insurance rates have more than tripled since the rebels began their campaign in the Red Sea, while at least one major shipping line has diverted to the longer alternative route around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Opposition lawmakers, critics of the government, and ordinary citizens have denounced the proposal on the grounds that it brings no immediate benefit to Sri Lanka. The Leader of the Opposition Sajith Premadasa, for instance, questioned the need for such a campaign at a time when people were reeling from grinding austerity, including an unpopular Value-Added Tax which has led to massive price hikes nearly everywhere, and on every item.

Predictably, the move has also been condemned as hypocritical: while forcing Sri Lankans to practice economies at home, the government is doing the exact opposite abroad, and what’s worse, as the country’s leading political and foreign policy commentator Dr Dayan Jayatilleka observes, in a conflict that is “not our fight.”

According to political researcher and archivist Uthpala Wijesuriya, however, the problem hasn’t just to do with cost, but also with capability. While there has been no shortage of supporters of the proposal who confidently point at the Sri Lankan Navy’s past successes, including its operations against illegal drug peddling in the Arabian Sea and its supposedly untarnished historical record, the Navy relies almost exclusively on vessels gifted by foreign governments which have the latest capabilities. “The question in that sense isn’t whether we have money for these kinds of operations, but whether we have the capabilities we need and if not, who is going to give them to us,” Wijesuriya argues.

This is a valid concern. On the other hand, though, former Chief Hydrographer of the Sri Lankan Navy Rear Admiral Y. N. Jayarathna (Retd.) sees the proposal as a massive investment opportunity for the country’s military. He estimates that Sri Lanka’s OPVs require equipment like thermal cameras and stabilised platforms, and argues that the government’s decision could spur investments in such “operational necessities.” While conceding that the media may portray the government as a “US partner” vis-à-vis its operations in the Red Sea, he contends that it is time the Navy extends its activities to areas like the Gulf of Yemen and the Arabian Sea in partnership with other countries.

At the same time, however, international relations commentator Rathindra Kuruwita argues that there is a manpower problem in the military. “Motivation is at an all-time low in the army and the navy, because their members are feeling the impact of austerity, reduced food rations, and so on.” Against such a backdrop, Kuruwita says that no number of investments would motivate them to embark on such a risky mission in the Red Sea.

Moreover, perceptions of the Sri Lankan government joining up with US forces could make Sri Lanka vulnerable to attacks abroad, especially since the Houthis have vowed retaliation on anyone joining the US coalition. This has only been compounded by what Kuruwita views as Sri Lanka’s problematic stance on the Gaza issue.

“On the one hand, we are voting with the rest of the Global South on Palestine at the UN,” he says. “Yet on the other, we are sending our youth to Israel to meet labour shortages there after they expelled Palestinian workers.” According to Kuruwita, the Gaza issue has become particularly sensitive for Muslims in Sri Lanka and everywhere else. “The government is now acting in a way that is hurting their feelings. That could generate a backlash in the not-too-distant future.” All that, he concludes, could boomerang on the country, particularly as the Houthis have vowed to attack any ship connected to Israel, and the Sri Lankan government is about to join the US, Israel’s number one military partner, in the Red Sea.

These developments underlie the immense complexities that Sri Lanka faces in the current geopolitical context. The decision to deploy vessels to the Red Sea has turned the Sri Lankan Navy into more than just a passive bystander; it has turned it into an active participant in the tensions erupting in the region. While supporters of the decision may make grandiose claims about the Navy’s past successes, there is no doubt it has opened a can of worms in Sri Lanka, the full repercussions of which will be felt in the months to come.

A version of this article appeared in The Diplomat on January 11, 2024.

The writer is an international relations analyst, independent researcher, and freelance columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Sri Lanka after the 2025 Deluge and the NPP’s Tidal Opportunity for 2026

“After me, the deluge,” is the widely used English translation of the notorious French expression, “Après moi, le deluge,” attributed to the 18th century King Louis XV of France and his indifference to what might happen after him. What happened afterwards was of course the French Revolution that led to the birth of the Republic amid the carnage of a people. The expression was quite common in the Sri Lankan parliament when it had quite a contingent of ‘Oxbridge purists and London practicals’. It was a favourite phrase of Dr. NM Perera, in particular, to deride the last budget of a government on its last legs before an election. The phrase takes a different meaning now, as the year 2025 ends and 2026 begins.

2025 was the year of the deluge, and 2026 is the year after it. The NPP government is not a falling regime before a deluge, but the regime that is at the helm to steer the country after the deluge. As many have said many times before, the JVP, which is the NPP’s creator and command centre, was the cause of two political deluges in Sri Lanka with far few benefits and far more griefs. It is now the epicentre of state power with the responsibility to restore the country’s habitats and infrastructure that have been devastated by Cyclone Ditwah and never ending rains. Engels called history, “the most cruel of all goddesses,” but even as it repeats history does give more than a second chance for political comebacks. Will the JVP/NPP take this second chance literally ‘at the flood’ and lead the country on to restoration and normalcy, if not fortune itself? That is the question.

The NPP government has been in power for more than a year now – after its preferential win in the presidential election and a historic landslide victory in the parliamentary election. Its performance to date has been moderately good, but not spectacularly great. As the old hard tasking schoolmaster would say: Not too good, not too bad! At the same time and in fairness to the NPP government, it is pertinent to ask which Sri Lankan government past has been spectacularly great at any time? How many have been even moderately good? Which government or country anywhere in the world now has fewer crises, less chaos, no state oppression, or greater public goodwill than the NPP government in Sri Lanka?

Such a situation is elusive to most countries in the world, and more so as the world waits for the second year of the second term of the Trump presidency. For Trump’s opponents in America, the New Year has brought a spark with the rousing swearing in of Zohran Mamdani on New Years Day, as New York City’s new Mayor. More on that next week.

Police Vanities

In Sri Lanka, whatever general goodwill that is now there for the NPP government, it is almost entirely due to the satisfaction among a large number of people in all walks of life that this government is virtually corruption-free in comparison to any and all of its predecessors this century – which were all laden with corruption. But in fighting corruption, the government should be careful not to let the police forces go rogue and overboard, arresting people at their whim.

What is the point in arresting someone like Charitha Ratwatta over some warehouse tendering ten years ago? Or taking Douglas Devananda into custody for a pistol that went missing more than 15 years ago? What was the earthly purpose in a police team traveling to the University of Wolverhampton in the United Kingdom to investigate the university’s invitation to the Wickremesinghes? Did they go for fingerprints, and who authorized the expenses? What is it they could not have found out by communicating from Colombo.

No government anywhere has unlimited resources to arrest and indict everyone who has violated a law. Limited resources must be spent on pursuing and apprehending criminal people who are a clear and present threat to society, and for solving serious crimes. Are Charitha Ratwatta, Douglas Devananda or Ranil Wickremesinghe any threat to any one? When will there be answers to the Colombo murders of Lasantha Wickrematunge (2009), Wasim Thajudeen (2012) or Dinesh Schaffter (2022), or all the other killings that UNHRC calls ‘emblematic murders’? When there are so many mortal crimes waiting to be solved, wouldn’t it be a crime to waste scarce resources on political peccadillos to satisfy petty police vanities?

A goody-goody report card alone at the end of five years is not good enough to win a repeat election. There is never going to be another massive majority as there was in the 2024 November election. That history is not going to be repeated. But even to win a modest majority the NPP has to show results – not spectacular, but solid and that touch the people.

Major reform initiatives, such as in education and electricity, do by nature take a long time to consummate, but if there are no tangible results, there will be no vote dividends for the government from its two hitherto signature initiatives. Near term tangible results from these two initiatives will be – easy school placements in urban areas and improved school facilities in rural areas, and steady electricity supply at affordable rates. Any reform initiative without such results will be a pie in the sky for the voting people.

Growing List of Discontents

The government is also creating a growing list of disappointments and criticisms for want of action on campaign promises and foot-dragging on routine matters. The indecision over the timing of provincial council elections and playing selection games for appointing a permanent Auditor General are not signs of sincerity or transparency, but they are reminding people of the games that President Ranil Wickremesinghe was playing in postponing local elections and avoiding the appointment of a permanent IGP.

There is nothing to be gained by these games and it is important for the government to realize that the person it nominates to be the Auditor General should be palpably acceptable to all for competence and experience. No one should be appointed to a high position in government as reward for loyalty to the governing party. Otherwise, people will be reminded of the high post appointments that were routinely made by President Chandrika Kumaratunga.

While I have been critical of the somewhat over-the top criticisms of the government on the abolition of the PTA, the government is not doing itself any favours by drafting a new replacement law that includes the main flaws of the old PTA. It is unconscionable that someone could be held in custody for as long two years without being indicted with criminal charges even under the proposed new law.

There is also concern that with the government’s proposed nominees for the Office of Reparations, three out of the five members of the Office could be former defense officials. The purpose of these appointments should not be to reward retired defense officials for their support of the government, but to ensure that victims of war are given a sympathetic hearing by the Office, and that they are not made to feel intimidated by the presence of war veterans as members of the Office of Reparations.

Speaking at a Ministry New Year ceremony, Harshana Nanayakkara, the Minister of Justice and National Integration (a joint portfolio pregnant with promise), promised that the government will begin early in the new year, the long awaited “investigations into the complaints of enforced disappearances will commence.”

This is welcome news and the Minister has also added that when all citizens begin to feel that they are “acknowledged in their own language, treated fairly by the law, and safeguarded irrespective of their identity, it signifies that national integration is in progress.” We applaud the Minister’s noble sentiments for the New Year, and would hope that he will ‘operationalize them’ in the establishment of the Office of Reparations and in the annulling of the PTA.

After Ditwah and the Deluge

The elephant in the NPP cabinet room now is the aftermath of Ditwah and the deluge. Through an Extraordinary Gazette issued on December 31, the government has established a Presidential Task Force for Rebuilding Sri Lanka that will oversee all activities relating to post Ditwah rehabilitation, recovery and reconstruction operations. The Task Force of 25 members will be headed by Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, and will include another 10 Ministers (virtually half the cabinet), seven deputy ministers and senior officials, the Governor of the Western Province, as well as six civilian members. The Task Force will set up eight Committees that will be headed by sector ministers on subjects including Needs Assessment; the restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing for Affected Communities, Local Economies and Livelihoods, and Social Infrastructure; as well as Finance and Funding, Data & Information System, and Public Communication.

The Committee on Finance and Funding has already been appointed on December 1. Led by Anil Jayantha Fernando, Minister of Labour and Deputy Minister of Finance and Planning, the Committee includes the Governor of the Western Province, four senior officials and five industry captains from the Hayleys Group, John Keells, Aitken Spence, Brandix and LOLC Holdings. Three members of the Committee are also on the main Task Force, viz., Minister Fernando, WP Governor Hanif Yusuf who is also the President’s Special Representative for Foreign Investments, and Secretary Harshana Suriyapperuma of the Ministry of Finance.

When the Finance Committee was first announced in early December there were concerns about the five civilian slots being exclusively assigned to business leaders. The sprawling composition of the new Task Force, including six civilian members might be intended to address the earlier concerns. There are other matters as well which are appropriate for the government’s consideration.

First, the Task Force does not seem to include anyone with technical or engineering background. Even among the Ministers and government officials in the Task Force, ministries and departments overseeing, irrigation, roads and bridges, power, plantations and food and agriculture do not seem to be represented at all. Most noticeably, the National Building Research Organization (NBRO) does not seem to be given the technical prominence it deserves to be given at the highest level.

Second, the lack of inclusion of technical expertise and experience on the Task Force is all the more inexplicable in light of the criticisms of inclusion of others with backgrounds in election monitoring and journalism. This is similar to the silly appointments of fashion and clothing lines people to the Tsunami task force by President Kumaratunga twenty years ago.

Third, technical expertise will invariably have to be brought into many of the eight Committees that the Task Force will be setting up. But it is necessary and appropriate that the technical presence in the committees is reflected in the main Task Force itself.

Fourth, the descriptions of the Committee on Public Infrastructure and the Committee on Housing make references to ‘disaster resilience’ and ‘safe zones.’ These are NBRO’s bailiwicks and both are associated with the main technical cause of Sri Lanka’s recurrent disasters, namely landslides. The importance of highlighting this in the composition and the mandate of the Task Force should be obvious to every minister on the Task Force.

Fifth, the Committee on Data & Information and the Committee on Public Communication should include and disseminate all accurate information about landslides and the warnings about them. For this reason, NBRO experts should be given a prominent role in these two committees as well.

And sixth, none of the committee descriptions carry any allusion to tapping external resources both for technical expertise and for funding assistance. Sri Lanka needs both, and needs them badly. However, this matter is hardly addressed in the mandate of the Task Force and the committee assignments that flow from it. For what it is worth, I will repeat what I wrote earlier that it would be worth the effort for the President and his Task Force to reach out to the countries that undertook the projects of accelerated Mahaweli scheme, and ask for their support with the new restoration work that has now become necessary in their old catchment areas.

by Rajan Philips ✍️

Features

Education Reforms and Democratic Deficit: A Warning for Sri Lanka

Introduction

Education reforms are among the most consequential policy decisions a nation can undertake. They shape not only the intellectual capacity of future generations but also the economic resilience, social cohesion, democratic culture, and long-term sovereignty of a country. In Sri Lanka, education has historically functioned as a powerful engine of social mobility, equity, and national integration. From the mid-twentieth century onward, free education enabled generations from rural and disadvantaged backgrounds to access higher learning and professional careers, thereby contributing to nation-building and relative social stability.

Against this backdrop, any attempt to reform the education system without broad-based, meaningful stakeholder consultation carries profound risks. The growing perception that recent or proposed education reforms in Sri Lanka have been hurried, opaque, and insufficiently consultative signals a looming danger. Teachers, academics, students, parents, professional bodies, universities, trade unions, provincial authorities, and civil society actors increasingly express concern that they are being treated as passive recipients rather than active partners in reform.

The critical question, therefore, is not merely whether reforms will succeed or fail, but who will ultimately bear the cost of failure. Will political leaders and senior bureaucrats be held accountable, or will the burden fall disproportionately on students, families, and the nation as a whole? It is widely arguing that while political actors may face short-term criticism, it is the entire nation especially its youth, that will be penalized if education reforms proceed without inclusive consultation, contextual sensitivity, and long-term vision.

The Imperative for Education Reform in Sri Lanka

It must be acknowledged at the outset that education reform in Sri Lanka is not only desirable but imperative. The education system faces multiple, well-documented structural challenges, foremost among them a growing mismatch between educational outcomes and labour market demands. This disconnect is evident across disciplines, including STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) as well as HEMS, humanities, education, management, and the social sciences where limited integration with applied, vocational, and industry-relevant training constrains graduate employability. As a result, graduate unemployment and underemployment have become persistent features of the system, steadily eroding public confidence in the relevance, quality, and economic value of higher education.

Global competitiveness has declined as Sri Lanka struggles to keep pace with rapidly evolving knowledge economies. Regional and socioeconomic inequities remain entrenched, with rural, estate, and conflict-affected areas lagging behind urban centres in infrastructure, teacher availability, and learning outcomes. Public educational institutions from primary schools to universities remain chronically underfunded, while research output and innovation ecosystems are weak by international standards. Moreover, curricula at many levels continue to emphasize rote learning and examination performance over critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, and interdisciplinary learning. These deficiencies are real and demand reform. However, the legitimacy, sustainability, and effectiveness of reform depend not only on technical design but also on participatory governance and social consensus.

Sri Lanka introduced the more advanced National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) framework around 2004-2005 through the Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC), established under the TVEC Act No. 20 of 1990, with the objective of creating a unified, competency-based vocational education and training system. Subsequently, the Sri Lanka Qualifications Framework (SLQF) was established in 2012 to integrate the NVQ framework into a single, coherent national qualifications structure encompassing both higher education and vocational training. This integration was intended to ensure parity of esteem, transparency, and clear progression pathways across academic and vocational streams.

While periodic amendments and reforms are necessary to align the system with evolving international standards, such reforms should strengthen not curtail the fundamental principles and institutional integrity of the NVQ and SLQF frameworks. These foundational structures have been carefully designed to safeguard quality, mobility, and inclusivity, and any reform that undermines them risks weakening the coherence and credibility of Sri Lanka’s national qualifications system.

Participatory Governance and the Legitimacy of Reform

Education is not a purely technocratic domain. It is deeply embedded in culture, language, values, identity, and social aspirations. Consequently, reforms imposed from the top however well-intentioned often encounter resistance, misinterpretation, or unintended consequences when they fail to engage those who must implement and live with them. Participatory governance in education reform involves structured, transparent, and inclusive consultation processes that genuinely incorporate stakeholder feedback into policy design. This includes not only elite consultations with select experts but also systematic engagement with teachers’ unions, university senates, student bodies, parent-teacher associations, professional councils, provincial education authorities, and independent scholars.

When reforms are designed in isolation often driven by political expediency, external pressure, or short-term fiscal considerations the system becomes vulnerable to distortion and eventual collapse. Policies may appear coherent on paper but prove unworkable in classrooms, lecture halls, and rural schools. The absence of consultation undermines moral authority and weakens public trust, even before implementation begins.

Sri Lanka’s education system, particularly in the post-independence period, has evolved as a distinctive synthesis of Buddhist philosophy and selected Catholic and Western pedagogical principles, while consistently giving primacy to cultural continuity, family values, and social cohesion. Rooted in a civilizational history spanning over 2,500 years, education in Sri Lanka has never been merely a vehicle for skills transmission; it has functioned as a moral and cultural institution shaping disciplined, compassionate, and socially responsible citizens. Buddhist values such as mindfulness, ethical conduct, respect for knowledge, and social harmony have historically informed educational thinking, while the legacy of nearly five centuries of colonial engagement introduced institutional rigor, structured curricula, and global academic standards. Importantly, this hybrid model respected religious pluralism and ethnic diversity, allowing Buddhism to guide the philosophical core of education without marginalizing other faiths or traditions. Within this context, ad hoc deviations from established educational principles particularly those introduced without broad-based consultation become deeply contentious.

Proposals such as curtailing History from a core subject to a peripheral “basket” subject are therefore viewed not merely as curricular adjustments, but as symbolic ruptures with national memory, identity, and civic consciousness.

Many educators and scholars argue that while Sri Lanka must undoubtedly modernize and adapt to contemporary global demands, reform should aim to produce modern yet civilized citizens technically competent, historically grounded, and ethically anchored.

The long-standing British and Commonwealth-influenced education system, once widely respected for its balance of academic excellence and moral formation, demonstrates that modernization need not come at the expense of cultural depth. Meaningful reform, therefore, must proceed through inclusive dialogue, historical sensitivity, and collective ownership, ensuring that progress strengthens rather than erodes the intellectual and cultural foundations of Sri Lankan society.

Erosion of Trust: Teachers, Academics, and the Front-line of Education

The most immediate consequence of inadequate stakeholder consultation is the erosion of trust. Teachers and academics are the backbone of the education system. They translate policy into practice, mediate curriculum content, mentor students, and sustain institutional continuity across political cycles. When they perceive reforms as imposed rather than co-created, morale suffers. This erosion of trust often manifests as low ownership of reforms, passive compliance, or active opposition through trade unions and professional associations. In Sri Lanka, where teachers’ unions and university academics have historically played a significant role in public discourse, such opposition can quickly escalate into strikes, protests, and prolonged disruptions to learning.

Beyond organized resistance, there is a more insidious cost: disengagement. Teachers who feel dis-empowered may adhere mechanically to new directives without conviction or creativity. Academics may withdraw from curriculum development and institutional leadership, focusing instead on individual survival strategies. Over time, this hollowing out of professional commitment undermines educational quality far more than any single policy flaw.

Students and Parents: Anxiety, Uncertainty, and Silent Costs

Students and parents are often the least consulted yet most affected stakeholders in education reform. Sudden changes to curricula, assessment methods, language policies, or admission criteria create confusion and anxiety. Families invest years of effort, emotional energy, and financial resources based on existing educational pathways. Abrupt policy shifts can render these investments uncertain or obsolete. For students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, instability in education policy translates into lost opportunities. Transitional cohorts may suffer from poorly aligned syllabi, inadequately trained teachers, or unclear progression routes to higher education and employment. These losses are rarely captured in official evaluations but have lifelong consequences for individuals.

Once trust is lost among students and parents, even well-designed reforms struggle to gain acceptance. Education systems depend on shared belief in fairness, predictability, and merit. Without these, social legitimacy erodes, and private alternatives often expensive and unequal proliferate, further fragmenting the system.

Democratic Accountability and the National Public Good

From a governance perspective, bypassing consultation weakens democratic accountability. Education is not merely a sectoral policy area; it is a national public good with inter-generational consequences. Decisions taken today shape the cognitive, ethical, and civic capacities of citizens decades into the future. When reforms are developed without inclusive dialogue, they risk being narrow, urban-centric, or misaligned with ground realities.

Provincial disparities may widen as centrally designed policies fail to accommodate linguistic diversity, regional labour markets, and infrastructural constraints. Marginalized communities already facing barriers to quality education may be further excluded. Such outcomes contradict the foundational principles of Sri Lanka’s post-independence education philosophy, which emphasized equity, access, and national integration. Reforms that deepen inequality rather than reduce it undermine social cohesion and long-term stability.

Who Pays the Price When Reforms Fail?

The question of accountability lies at the heart of this debate. In the short term, politicians may face public criticism, media scrutiny, protests, or electoral backlash. However, history suggests that political accountability in complex policy domains like education is often diffuse and delayed. Governments change, ministers rotate portfolios, and policy architects move on to new roles.

In contrast, the nation pays an enduring price. Students become the silent victims, losing critical years of learning under unstable or poorly implemented policies. Employers confront a workforce ill-prepared for modern economic demands, necessitating costly retraining or reliance on foreign expertise. Universities struggle with incoherent mandates, fluctuating regulations, and declining international credibility. The cumulative effect is stagnation in human capital development the most critical resource for a small, resource-constrained country like Sri Lanka.

Long-Term National Consequences

In the long run, the costs of failed or poorly designed education reforms manifest in multiple dimensions. Economic productivity declines as skills mismatches persist. Brain drain accelerates as talented students and academics seek stability and opportunity abroad. Social frustration grows among youth who feel betrayed by a system that promised mobility but delivered uncertainty.

Such frustration can spill over into social unrest, political polarization, and declining trust in public institutions. National competitiveness weakens as innovation ecosystems fail to mature. No political narrative, however persuasive, can compensate for a generation that feels shortchanged by experimental or externally driven policies.

External Funding, Donor Influence, and Policy Sovereignty

A particularly sensitive dimension of contemporary education reform in Sri Lanka is the role of external funding and donor influence. In economically bankrupt or fiscally constrained countries, education reform funding from institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is common. Such funding can provide much-needed resources for infrastructure, teacher training, digitalization, and system modernization.

However, donor-funded reforms often come with policy conditionality, timelines, and performance indicators that may not fully align with national contexts. When reforms are hurried to meet funding milestones rather than educational realities, the risk of superficial compliance increases. There is a danger that reforms become single-sided approaches driven more by the logic of grants and loans than by pedagogical soundness and social consensus. Policy-makers and top bureaucrats must therefore exercise extreme caution when engaging with donor-driven reform agendas. Education, like health, is integral to the long-term health of a nation. Short-term fiscal relief should not come at the cost of policy sovereignty, institutional stability, or social trust.

The Role of Bureaucracy and Political Leadership

Senior bureaucrats and political leaders occupy pivotal positions in shaping education reform trajectories. Their responsibility extends beyond drafting policy documents and securing funding. They must act as stewards of the public interest, balancing economic constraints with educational integrity. This requires humility to acknowledge the limits of centralized expertise, openness to dissenting views, and commitment to transparent decision-making. Consultation should not be treated as a symbolic ritual or box-ticking exercise, but as a substantive process that can reshape policy direction. Failure to do so risks reducing education reform to an administrative experiment one conducted on the lives and futures of millions of young citizens.

Towards Inclusive, Sustainable Education Reform

Meaningful stakeholder consultation is not a procedural luxury; it is a strategic necessity. While genuine dialogue may slow the pace of reform, it ultimately strengthens both the quality and durability of outcomes. Inclusive engagement enables policymakers to identify blind spots, anticipate implementation challenges, and adapt reforms to diverse social and local contexts. More importantly, it fosters shared ownership, reduces resistance, and enhances long-term sustainability. When consultation is embedded in reform processes, policy initiatives evolve beyond short-term political agendas to become national missions that transcend electoral cycles and donor-driven timelines.

Instruments such as white papers, public hearings, pilot testing, independent evaluations, and phased implementation are essential for bridging the gap between policy intent and classroom reality. Sri Lanka possesses the intellectual capital and institutional experience to adopt such approaches provided the necessary political will is exercised.

Recent public discourse widely reflected across social media platforms and multiple information sources underscores the consequences of neglecting these principles. The inclusion of references to sexually explicit web-based content in a Grade 6 teaching module-later temporarily withdrawn-stands as a clear example of an uncoordinated and hastily executed intervention. This episode exposed serious deficiencies in the reform process, particularly the absence of meaningful stakeholder consultation and the lack of rigorous academic, ethical, and pedagogical review prior to implementation.

The present Sri Lanka government rose to power with the explicit backing of civil society activists, university academics, and progressive intellectuals who have long championed pro-people values. Central to this moral and political support were firm commitments to free education, equal opportunities for poor and marginalized communities, national sovereignty, the protection of valuable historical and cultural heritage, and respect for all religious beliefs and sentiments. These principles resonated deeply with the public, particularly with students, teachers, and parents who viewed education not as a commodity but as a social right and a cornerstone of social justice. The government’s legitimacy, therefore, was built not merely on electoral victory but on a perceived ethical alignment with pluralism, inclusivity, and democratic participation.

From the standpoint of education reform, however, there is a growing and troubling contradiction between these proclaimed values and the government’s actual conduct. Policies and reform initiatives increasingly appear to be designed and advanced with minimal consultation, technocratic haste, and an over reliance on elite or external inputs, sidelining the very constituencies that once formed its moral backbone. This dissonance risks hoodwinking the public using the language of equity, free education, and reform while pursuing approaches that undermine participatory decision-making and social trust.

When political movements invoke progressive ideals but act in ways that contradict them, especially in a sensitive domain like education, the result is public disillusionment. Over time, such contradictions do not merely weaken specific reforms; they erode confidence in political movements themselves, turning education reform from a collective national endeavor into yet another instrument of political expediency.

Conclusion

If education reforms in Sri Lanka continue to be pursued without wide, sincere, and institutionalized stakeholder consultation, the immediate political consequences may indeed appear manageable. Ministers may weather criticism, senior officials may be transferred, and compliance reports to external agencies may be duly completed. However, this apparent surface-level stability masks a far deeper and more enduring national cost. The erosion of trust between policymakers and the education community such as teachers, academics, students, and parents will accumulate silently but steadily.

Reforms conceived in isolation risk weakening institutional morale, fragmenting professional consensus, and fostering cynicism among the youth, who will increasingly perceive education not as a pathway to empowerment but as an arena of uncertainty and imposed change. While individual decision-makers may evade lasting accountability, the collective penalty will be borne by society at large, particularly by generations whose intellectual formation and civic confidence are shaped within these contested systems.

Education reform should be a unifying national project one that builds shared purpose, strengthens social cohesion, and nurtures critical yet responsible citizens. When consultation is inclusive and genuine, reform can inspire confidence, encourage innovation, and align modernization with cultural continuity. In its absence, however, reform becomes divisive, alienating those entrusted with implementation and confusing those meant to benefit.

Education is not a domain for hurried experiments, technocratic shortcuts, or externally scripted solutions divorced from local realities. It is the bedrock of national resilience, sovereignty, and long-term development. To disregard this is not merely a policy miscalculation; it is a gamble with Sri Lanka’s future, one whose costs may take decades to repair and whose consequences the nation can ill afford to ignore.

Finally, I would like to end by quoting a thought that has immensely helped shape Finnish education in its current strength. Finnish education scholar Pasi Sahlberg, whose work has profoundly influenced Finland’s globally admired education system, aptly reminds us: “Educational change depends on what teachers do and think; it is as simple and as complex as that.”

Prof. M. P. S. Magamage is a senior academic and former Dean of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka. He is an accomplished scholar with extensive international exposure. Prof. Magamage is a Fulbright Scholar, Indian Science Research Fellow, and Australian Endeavour Fellow, and has served as a Visiting Professor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, USA. These views are entirely personal and do not represent any institution, association, or organization.E mail; magamage@agri.sab.ac.lk

by Prof. MPS Magamage ✍️

Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka

Features

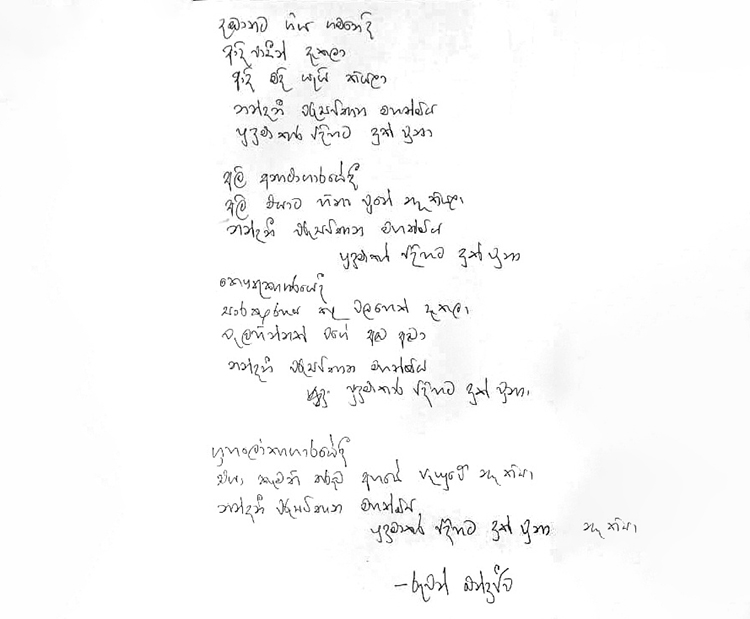

Nandani Warusavithana’s sorrow

[Disclaimer: neither I nor Ruwan Bandujeewa know of a Nandani Warusavithana. If such a person does exist, please note that none of what follows has anything to do with her. It was a random name that the poet, Bandujeewa, came up with perhaps in the part-delirium of a persisting fever sometime in March 2025]

I’ve mostly met Ruwan Bandujeewa at the ‘Kavi Poth Salpila’ run by poet, novelist and publisher Mahinda Prasad Masimbula. That’s at the annual Book Fair. That’s the only stall I visit and I do so because for many writers, especially poets, it is a meeting point. I know that I will meet a few, whatever the time of day. We talk. I cherish the conversations because I always learn something from poets, especially those writing in Sinhala.

So we talk. Have tea.

We meet randomly at book launches, either at the Library Services Board auditorium or the Mahaweli Centre. Talk. Tea.

It is rare that we plan to meet. We did last week. At some point he told me about Nandani Warusavithana. Yes, the fictional character. I asked him how he came by that name. He laughed, almost in embarrassment, and said he did not know.

Here’s the context. As mentioned, he had a fever that kept him home for several weeks. On a whim, he had explored AI and tried his hand at fusing African and Chinese music. As he fiddled around he discovered that he could ‘sing’ as in, he would voice some words and the engine would generate melody and music. It would correct the obvious flaws of rendition. So he had written a few songs.

One was about the palaa-pala of moonlight, drawing from the superstitions related to geckos, i.e. what is portended by the place on the body that a gecko might fall. In Sinhala it is referred to as hoonu-palaa-pala or simply hoonu-saasthara. ‘Moonlight’ was the poetic twist. If it fell on the right eyebrow, what would it mean? If it fell on the shoulder, then? Such questions he answered in the song. I told him that he could publish a collection of these fever-day songs and call it ‘handa-eliye palaa-pala.’ He laughed.

Then he mentioned Nandani Warusavithana. Here goes:

Having visited Dambana

and met the ancients there

she noted they weren’t ancient enough for her

Miss Nandani Warusavitharana was inconsolably distraught

At the elephant orphanage

since not a single elephant smiled at her

Miss Nandani Warusavitharana was inconsolably distraught

At the museum

upon seeing a taxidermy mount of a bear

weeping like a female bear that had lost her cubs

Miss Nandani Warusavitharana was inconsolably distraught

At the planetarium

unable to find in the sky

that one star she loved the most

Miss Nandani Warusavitharana was inconsolably distraught

Simple stuff. Hilarious too. And that’s how this ‘works,’ at least for me. It reminded me of a conversation I had with my Grade 6 class teacher, Sunimal Silva. I wasn’t his best student but not the worst either. I did nothing noteworthy in that Grade 6 classroom.

Anyway, more than thirty years later, I happened to take my daughters to the school’s swimming pool because I had heard of a coach who was kind and grandfatherly. It was him. We had met many times over the years, so the recognition was immediate.

Are these your daughters? I will coach them!’

I didn’t even have to ask.

‘Is this your wife?’

So I made the introductions. Then he declared, in Sinhala, ‘of all the students I’ve taught throughout my career as a teacher, he is the one who did absolutely nothing with the skills he had.’

I couldn’t help but smile. That was the way he expressed affection, I now feel. And now, thinking of that moment, it occurs to me that Sunimal Sir actually believed I had skills.

I just responded, ‘sir, asthma thrupthiya neveida vadagath vanne (isn’t contentment what matters most)?’

His tone and demeanour changed immediately: ‘ow, ehemanam hariyatama hari (yes, if that’s the case, it’s all good).’

I think I was just being clever. Somehow, over the years, I had acquired some decent level of competence when it comes to repartee.

Nandani Warusavithana is a random name that came to my friend from who knows where, but her grief is common to us all to the extent that we are enamoured with expectations, the splendour that’s in the advertisement but is less than promised, and sense of the exotic in place, artefact and love that is anticipated with such relish but disappoints and the promised land that’s non-existent.

Contentment. That seems to be the key factor.

In Uruvela, a long time ago, the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, elaborated on this to the Kassapas. It’s in the Santuṭṭhi Sutta (ref the Anguttara Nikaya or the Numerical Discourses of the Buddha).

‘When you’re content with what’s blameless, trifling, and easy to find, you don’t get upset about lodgings, robes, food, and drink, and you’re not obstructed anywhere,’ the Kassapas were told.

Not becoming agitated is what it is about. For example if a monk does not get a robe he should not be agitated, and if he does get one he should use it ‘without being tied to it, un-infatuated with it, nor blindly absorbed in it, seeing the danger in it, understanding the escape.’

Do we? Can we? Miss Nandani Warusavithana couldn’t. Her fascinations were mild, ours may not be. Ruwan Bandujeewa, as usual, touched a nerve. And laughed about it. At himself, at me, at all of us. I am enriched. Fascinated. Time to ‘see the danger.’ Time to stop.

Malinda Seneviratne is a freelance writer. malindadocs@gmail.com.

by Malinda Seneviratne ✍️

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance