Features

Remembering Sumithra

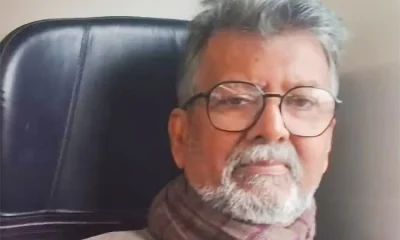

By Uditha Devapriya

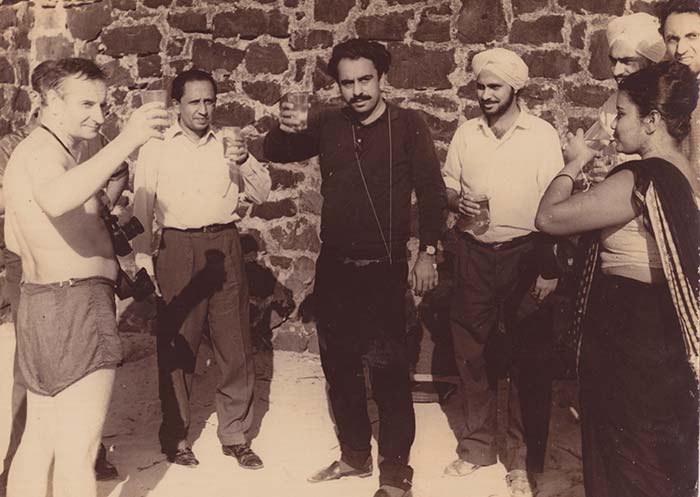

One of the defining auteurs of Sri Lankan cinema, Sumitra Peries made an indelible and enduring contribution to women’s filmmaking in South Asia.Satyajit Ray once reportedly called Lester James Peries, the Sri Lankan film director who passed away at the age of 99 in April 2018, his “only relation east of Suez.” Lester’s wife Sumitra, who was his closest colleague, and who passed away on 19 January 2023 at the age of 87, had her first encounter with Ray in Mexico in 1963.

By that point, Sumitra had returned from her studies in England and earned a reputation as an assistant director and editor. She recalled that Ray had been “kind and courteous”, but a little disdainful of her profession. When she told him of what she did, the Indian director had been somewhat unimpressed, comparing her work to that of a cutter. Temperamentally candid, Sumitra had fired back, “Well, I’m glad I’m not just a cutter!”

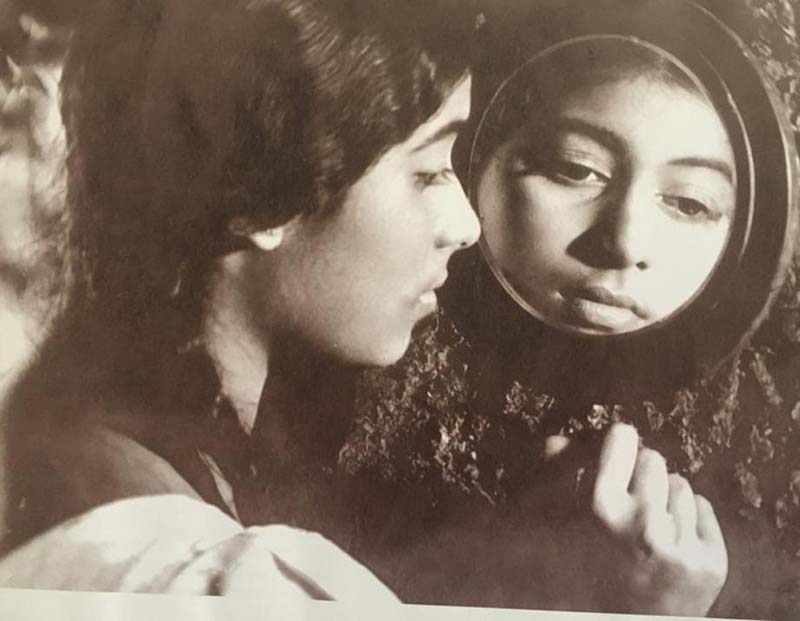

Sumitra Peries did not remain a cutter for long. After working on her husband’s films, she made her directorial debut in 1978 with Gehenu Lamayi (Girls). The film established the themes that would preoccupy her for the rest of her career: the rift between rich and poor, the torments of adolescent love, and most significantly, the agony of being a woman in Sri Lanka and in South Asia. Sumitra’s work thus clearly stands out in the pantheon of regional cinema, in ways that critics have so far not done justice to.

Sri Lanka has long been orientalised for its sandy beaches and its cultural sites. In the first half of the 20th century, the colonial government helped establish a local cinema in the capital, Colombo. The first Sri Lankan film, Kadawunu Poronduwa (Broken Promise), came out in 1947, a year before the country obtained its independence.From its inception, however, local films were derided as derivative, because they were shot abroad and were felt to be too artificial, contrived, and unauthentic.

Seeking a better and more grounded cinema, a group of Westernised, urban middle-class artistes moved into this void. The most prominent of them was Lester James Peries, who had worked for some time at the official propaganda arm of the Sri Lankan government, the Government Film Unit (GFU), and who had imbibed the aesthetics of Italian neo-realism and the British documentary. Peries’s first film, Rekava (1956), came out around the same time that Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali did in India. Like Ray’s film, it was lukewarmly received by local critics, but went on to establish the country on the world map.

Sumitra Peries subsequently established herself in this circle, but she came from a very different background. Born Sumitra Gunawardena on 24 March 1935, she hailed from a family of affluent arrack distillers on her mother’s side and a family of radical, socialist, and anti-imperialist activists on her father’s. Her two paternal uncles, Philip and Robert, had been actively involved in the struggle against British colonialism: a far cry from the middle-class, Westernised, and Anglicised milieu of her husband.

Born in the southwestern village of Payagala, Sumitra was raised in Avissawella, located roughly 30 miles from Colombo. Initially she was educated at the local school, St Mary’s College, where she mingled with her social peers as well as more deprived sections of her village. Though not part of an urban elite, her mother, Harriet Wickramasinghe, moved around in important circles, “playing tennis with her sari on.” In contrast to her two uncles, her father, Henry, adjusted to his wife’s milieu, “practising as a proctor.”

Sumitra’s earliest influence was her mother. Through a distillery that her own mother, or Sumitra’s grandmother, had set up, “she took responsibility for the family.” Sumitra’s father, on the other hand, “sought and went after less practical pursuits.”

Their social status did not limit their daughter’s social interactions. “We lived in the most basic of settings,” she remembered. “No electricity, no proper running water, certainly no attached bathrooms. Only through a small radio did we get to know of what was happening in the outside world. As such I would get out and meet other people, including the sons and daughters of estate workers. I revelled in these encounters.”

Colombo lay a world away from all this. When Sumitra turned 13, a month after Sri Lanka gained independence from Great Britain, her family decided to send her there to study. Her new home was to be at Gower Street, in Colombo 4. It was conveniently located right next to her new school, Visakha Vidyalaya, the island’s leading Buddhist girls’ school. “I took time to adjust to my new setting, but eventually got used to life in Colombo.”

Among her siblings, Sumitra was closest to her elder brother, Gamini or “Kuru.” When their mother died two years after they shifted to Colombo, he entered a long period of depression. “My brother was a very temperamental man. He left everything to us and left the country. We did not know where he was, or whether he planned to return.”

A few years later, he got in touch with Sumitra: he was in Malta, and he wanted her to join him. Though she was engaged with her higher studies, she heeded his call. She packed her belongings and soon boarded a P&O Liner. “I was not quite 21.”

At Malta, Sumitra joined her brother and a bohemian coterie of friends. Together they sailed across the Mediterranean, dropping anchor in the French Riviera. At Saint-Tropez near the Riviera, Sumitra spotted Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim filming And God Created Woman (1956). It was the first time she had seen a film being made.

By then she was at a loss: “I badly wanted to be a psychiatrist. My brother felt it would be best if I went to Switzerland, to study at the Jung Institute.”

Just as Sumitra was about to embark on her higher education, however, Gamini decided to return to Sri Lanka. “This led to a series of misadventures that ended in Paris. There I had a vague desire to settle in the Left Bank.” Fate, however, had other plans for her.

Sri Lanka had just established a Legation in Paris. The country’s Envoy, Vernon Mendis, got in touch with Sumitra and boarded her at his official residence. It was here, at the Legation, that she met Lester James Peries. “He told me to go to England and study film. He felt I was wasting my talents in Paris. Since I had nothing to lose, I heeded his advice.”

Sumitra enrolled herself at the London School of Film Technique (LSFT) in Brixton, the sole female in a class of white and middle-class males.

During her years at the LSFT, she grew very close to the filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, who taught her class. Lindsay had already met Lester a few years before. Needless to say, he and Sumitra became very good friends. Their association grew so strong that in her later visits to England, “we would meet, and he would cook for me.”

Sumitra successfully completed her studies. But finding a job was challenging. “Those days, if you weren’t a member of a union, it was not easy to enter the industry.”

Armed with her qualification, she knocked on the doors of Elizabeth Mai-Harris, one of Britain’s leading subtitling firms. “I passionately argued my case. Fortunately, they believed in me and took me in. My fluency in French may have helped.”

Sometime later, though, she encountered another problem: “I started growing homesick.” Her elder brother ordered her to return. She thus came back home.Sumitra then found work as an assistant to Lester Peries, onboard his film Sandesaya (The Message, 1960). “I was the sole female crew member. We were shooting a world away from Colombo. A tough ordeal for any woman, but I grew to enjoy it.”

She also grew close to Lester. Four years later, in 1964, she married him.

Making full use of her editing skills, Sumitra wound up as her husband’s closest aide. She worked on all his films in the 1960s: Gamperaliya (1963), Delovak Athara (1966), Ran Salu (1967), Golu Hadawatha (1968), and Akkara Paha (1969).

These films won awards and accolades abroad: Gamperaliya secured the Golden Peacock or the Best Film Award at the 3rd Indian International Film Festival and the Golden Head of Palenque at the Mexico Film Festival, while Ran Salu won the Gandhi Award at New Delhi and was telecast on Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Ireland.

Recalling her years as an editor, she once told me, “What fascinated me during these years was the mise-en-scène. To achieve the right cut is harder than you think. You need to train your eyes and you need to make the decision then and there.” Contrary to what Satyajit Ray may have felt, then, her job was hardly that of a mere cutter.

After a stint in France and a few idle years, Sumitra carved her path as director with Gehenu Lamai in 1978. Based on a popular novel, it became an instant success wherever it went: the British press in particular loved it, with David Robinson of The Times lauding it for its “holistic feminine sensibility.”

Its success emboldened her to make nine more films: Ganga Addara (By the Bank of the River, 1980), Yahalu Yeheli (Friends, 1982), Maya (1984), Sagara Jalaya Madi Handuwa Oba Sanda (A Letter Written in the Sand, 1988), Loku Duwa (The Eldest Daughter, 1994), Duwata Mawaka Misa (Mother Alone, 1997), Sakman Maluwa (The Pleasure Garden, 2003), Yahaluwo (Friends, 2007) and Vaishnavee (The Goddess, 2018).

Apart from her work in film, Sumitra also worked in television, having gained six months’ work experience at the French Radio and Television Institute (ORTF) in Paris in 1971. She served as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to France and Spain from 1995 to 1998, and did her part to secure international goodwill for the country at a time of rising ethnic tensions and separatist conflict.

With Yahaluwo and Vaishnavee behind her, she was toying with several ideas, as late as 2022, for her next venture. Humble to a fault, she remained open to outsiders, in particular young, aspiring directors who would constantly seek her advice.

Sumitra’s passing, given all this, signifies an end and a passing of an era. Linked through her husband to some of the most exciting strides in the arts of post-independence Sri Lanka, she nevertheless carved her own path. Indeed, as Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin rightly argues in her biography, Sumitra Peries: Sri Lankan Filmmaker, while she is considered a mere appendage to her husband’s work, her career was distinct on its own right.

Moreover, unlike South Asian women filmmakers from her time – including Fatma Begum, Parveen Rizvi, Shamin Ara, Kohinoor Akhter, and Aparna Sen – she did not come to the director’s chair as an actress. In that sense Sumitra, with her education in the West, was a definitive precursor to the likes of Mira Nair and Deepa Mehta. This point has not yet been appreciated or acknowledged by historians of the regional cinema.

A product of a rural upper middle-class, Sumitra Peries remained intimately attached to her people, in particular women. Her films, which dwell considerably on their agonies and their torments, are in that sense an enduring testament, not just to her craft, but also to a bygone era in filmmaking – both in Sri Lanka and in South Asia.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst based in Sri Lanka who contributes to a number of publications on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Trade preferences to support post-Ditwah reconstruction

The manner in which the government succeeded in mobilising support from the international community, immediately after the devastating impact of Cyclone Ditwah, may have surprised many people of this country, particularly because our Opposition politicians were ridiculing our “inexperienced” government, in the recent past, for its inability to deal with the international community effectively. However, by now it is evident that the government, with the assistance of the international community and local nongovernmental actors, like major media organisations, has successfully managed the recovery efforts. So, let me begin by thanking them for what they have done so far.

Yet, some may argue that it is not difficult to mobilise the support for recovery efforts from the international community, immediately after any major disaster, and the real challenge is to sustain that support through the next few weeks, months and years. Because the recovery process, more specifically the post-recovery reconstruction process, requires long-term support. So, the government agencies should start immediately to focus on, in addition to initial disaster relief, a longer-term strategy for reconstruction. This is important because in a few weeks’ time, the focus of the global community may shift elsewhere … to another crisis in another corner of the world. Before that happens, the government should take initiatives to get the support from development partners on appropriate policy measures, including exceptional trade preferences, to help Sri Lanka in the recovery efforts through the medium and the long term.

Use of Trade Preferences to support recovery and reconstruction

In the past, the United States and the European Union used exceptional enhanced trade preferences as part of the assistance packages when countries were devastated by natural disasters, similar to Cyclone Ditwah. For example:

- After the devastating floods in Pakistan, in July 2010, the EU granted temporary, exceptional trade preferences to Pakistan (autonomous trade preferences) to aid economic recovery. This measure was a de facto waiver on the standard EU GSP (Generalised Scheme of Preferences) rules. The preferences, which were proposed in October 2010 and were applied until the end of 2013, effectively suspended import duties on 75 types of goods, including textiles and apparel items. The available studies on this waiver indicate that though a significant export hike occurred within a few months after the waiver became effective it did not significantly depress exports by competing countries. Subsequently, Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014.

- Similarly, after the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal, the United States supported Nepal through an extension of unilateral additional preferences, the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP). This was a 10-year initiative to grant duty-free access for up to 77 specific Nepali products to aid economic recovery after the 2015 earthquakes. This was also a de facto waiver on the standard US GSP rules.

- Earlier, after Hurricanes Mitch and Georges caused massive devastation across the Caribbean Basin nations, in 1998, severely impacting their economies, the United States proposed a long-term strategy for rebuilding the region that focused on trade enhancement. This resulted in the establishment of the US Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA), which was signed into law on 05 October, 2000, as Title II of the Trade and Development Act of 2000. This was a more comprehensive facility than those which were granted to Pakistan and Nepal.

What type of concession should Sri Lanka request from our development partners?

Given these precedents, it is appropriate for Sri Lanka to seek specific trade concessions from the European Union and the United States.

In the European Union, Sri Lanka already benefits from the GSP+ scheme. Under this arrangement Sri Lanka’s exports (theoretically) receive duty-free access into the EU markets. However, in 2023, Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, that is, the ratio of preferential imports to GSP+ eligible imports, stood at 59%. This was significantly below the average utilisation of other GSP beneficiary countries. For example, in 2023, preference utilisation rates for Bangladesh and Pakistan were 90% and 88%, respectively. The main reason for the low utilisation rate of GSP by Sri Lanka is the very strict Rules of Origin requirements for the apparel exports from Sri Lanka. For example, to get GSP benefits, a woven garment from Sri Lanka must be made from fabric that itself had undergone a transformation from yarn to fabric in Sri Lanka or in another qualifying country. However, a similar garment from Bangladesh only requires a single-stage processing (that is, fabric to garment) qualifies for GSP. As a result, less than half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports to the EU were ineligible for the preferences in 2023.

Sri Lanka should request a relaxation of this strict rule of origin to help economic recovery. As such a concession only covers GSP Rules of Origin only it would impact multilateral trade rules and would not require WTO approval. Hence could be granted immediately by the EU.

United States

Sri Lanka should submit a request to the United States for (a) temporary suspension of the recently introduced 20% additional ad valorem duty and (b) for a programme similar to the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP), but designed specifically for Sri Lanka’s needs. As NTPP didn’t require WTO approval, similar concessions also can be granted without difficulty.

Similarly, country-specific requests should be carefully designed and submitted to Japan and other major trading partners.

(The writer is a retired public servant and can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

by Gomi Senadhira

Features

Lasting power and beauty of words

Novelists, poets, short story writers, lyricists, politicians and columnists use words for different purposes. While some of them use words to inform and elevate us, others use them to bolster their ego. If there was no such thing called words, we cannot even imagine what will happen to us. Whether you like it or not everything rests on words. If the Penal Code does not define a crime and prescribe a punishment, judges will not be able to convict criminals. Even the Constitution of our country is a printed document.

A mother’s lullaby contains snatches of sweet and healing words. The effect is immediate. The baby falls asleep within seconds. A lover’s soft and alluring words go right into his or her beloved. An army commander’s words encourage soldiers to go forward without fear. The British wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s words still ring in our ears: “… we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender …”

Writers wax eloquent on love. English novelist John Galsworthy wrote: “Love is no hot-house flower, but a wild plant, born of a wet night, born of an hour of sunshine; sprung from wild seed, blown along the road by a wild wind. A wild plant that, when it blooms by chance within the hedge of our gardens, we call a flower; and when it blooms outside we call a weed; but flower or weed, whose scent and colour are always wild.” While living in a world dominated by technology, we often hear a bunch of words that is colourless and often cut to verbal ribbons – “How R U” or “Luv U.” Such words seem to squeeze the life out of language.

Changing medium

Language is a constantly changing medium. New words and forms arrive and old ones die out. Whoever thought that the following Sinhala words would find a place in the Oxford English Dictionary? “Asweddumize, Avurudu, Baila, Kiribath, Kottu Roti, Mallung, Osari, Papare, Walawwa and Watalappan.” With all such borrowed words the English language is expanding and remains beautiful. The language helps us to express subtle ideas clearly and convincingly.

You are judged by the words you use. If you constantly use meaningless little phrases, you will be considered a worthless person. When you read a well-written piece of writing you will note how words jump and laugh on the paper or screen. Some of them wag their tails while others stand back like shy village belles. However, they serve a useful purpose. Words help us to write essays, poems, short stories and novels. If not for the beauty of the language, nobody will read what you write.

If you look at the words meaningfully, you will see some of them tap dancing while others stand to rigid attention. Big or small, all the words you pen form part of the action or part of the narrative. The words you write make your writing readable and exciting. That is why we read our favourite authors again and again.

Editorials

If a marriage is to succeed, partners should respect and love each other. Similarly, if you love words, they will help you to use them intelligently and forcefully. A recent survey in the United States has revealed that only eight per cent of people read the editorial. This is because most editorials are not readable. However, there are some editorials which compel us to read them. Some readers collect such editorials to be read later.

Only a lover of words would notice how some words run smoothly without making a noise. Other words appear to be dancing on the floor. Some words of certain writers are soothing while others set your blood pounding. There is a young monk who is preaching using simple words very effectively. He has a large following of young people addicted to drugs. After listening to his preaching, most of them have given up using illegal drugs. The message is loud and clear. If there is no demand for drugs, nobody will smuggle them into the country.

Some politicians use words so rounded at the edges and softened by wear that they are no longer interesting. The sounds they make are meaningless and listeners get more and more confused. Their expressions are full of expletives the meaning of which is often soiled with careless use of words.

Weather-making

Some words, whether written or spoken, stick like superglue. You will never forget them. William Vergara in his short essay on weather-making says, “Cloud-seeding has touched off one of the most baffling controversies in meteorological history. It has been blamed for or credited with practically all kinds of weather. Some scientists claim seeding can produce floods and hail. Others insist it creates droughts and dissipates clouds. Still others staunchly maintain it has no effect at all. The battle is far from over, but at last one clear conclusion is beginning to emerge: man can change the weather, and he is getting better at it.”

There are words that nurse the ego and heal the heart. The following short paragraph is a good example. S. Radhakrishnan says, “In every religion today we have small minorities who see beyond the horizon of their particular faith, not through religious fellowship is possible, not through the imposition of any one way on the whole but through an all-inclusive recognition that we are all searchers for the truth, pilgrims on the road, that we all aim at the same ethical and spiritual standard.”

There are some words joined together in common phrases. They are so beautiful that they elevate the human race. In the phrase ‘beyond a shadow of doubt’, ‘a shadow’ connotes a dark area covering light. ‘A doubt’ refers to hesitancy in belief. We use such phrases blithely because they are exquisitely beautiful in their structure. The English language is a repository of such miracles of expression that lead to deeper understanding or emphasis.

Social media

Social media use words powerfully. Sometimes they invent new words. Through the social media you can reach millions of viewers without the intervention of the government. Their opinion can stop wars and destroy tyrants. If you use the right words, you can even eliminate poverty to a great extent.

The choice of using powerful words is yours. However, before opening your mouth, tap the computer, unclip a pen, write a lyric or poem, think twice of the effect of your writing. When you talk with a purpose or write with pleasure, you enrich listeners and readers with your marvellous language skills. If you have a command of the language, you will put across your point of view that counts. Always try to find the right words and change the world for a better place for us to live.

By R. S. Karunaratne

karunaratners@gmail.com

Features

Why Sri Lanka Still Has No Doppler Radar – and Who Should Be Held Accountable

Eighteen Years of Delay:

Cyclone Ditwah has come and gone, leaving a trail of extensive damage to the country’s infrastructure, including buildings, roads, bridges, and 70% of the railway network. Thousands of hectares of farming land have been destroyed. Last but not least, nearly 1,000 people have lost their lives, and more than two million people have been displaced. The visuals uploaded to social media platforms graphically convey the widespread destruction Cyclone Ditwah has caused in our country.

The purpose of my article is to highlight, for the benefit of readers and the general public, how a project to establish a Doppler Weather Radar system, conceived in 2007, remains incomplete after 18 years. Despite multiple governments, shifting national priorities, and repeated natural disasters, the project remains incomplete.

Over the years, the National Audit Office, the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA), and several print and electronic media outlets have highlighted this failure. The last was an excellent five-minute broadcast by Maharaja Television Network on their News First broadcast in October 2024 under a series “What Happened to Sri Lanka”

The Agreement Between the Government of Sri Lanka and the World Meteorological Organisation in 2007.

The first formal attempt to establish a Doppler Radar system dates back to a Trust Fund agreement signed on 24 May 2007 between the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). This agreement intended to modernize Sri Lanka’s meteorological infrastructure and bring the country on par with global early-warning standards.

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations established on March 23, 1950. There are 193 member countries of the WMO, including Sri Lanka. Its primary role is to promote the establishment of a worldwide meteorological observation system and to serve as the authoritative voice on the state and behaviour of the Earth’s atmosphere, its interaction with the oceans, and the resulting climate and water resources.

According to the 2018 Performance Audit Report compiled by the National Audit Office, the GoSL entered into a trust fund agreement with the WMO to install a Doppler Radar System. The report states that USD 2,884,274 was deposited into the WMO bank account in Geneva, from which the Department of Metrology received USD 95,108 and an additional USD 113,046 in deposit interest. There is no mention as to who actually provided the funds. Based on available information, WMO does not fund projects of this magnitude.

The WMO was responsible for procuring the radar equipment, which it awarded on 18th June 2009 to an American company for USD 1,681,017. According to the audit report, a copy of the purchase contract was not available.

Monitoring the agreement’s implementation was assigned to the Ministry of Disaster Management, a signatory to the trust fund agreement. The audit report details the members of the steering committee appointed by designation to oversee the project. It consisted of personnel from the Ministry of Disaster Management, the Departments of Metrology, National Budget, External Resources and the Disaster Management Centre.

The Audit Report highlights failures in the core responsibilities that can be summarized as follows:

· Procurement irregularities—including flawed tender processes and inadequate technical evaluations.

· Poor site selection

—proposed radar sites did not meet elevation or clearance requirements.

· Civil works delays

—towers were incomplete or structurally unsuitable.

· Equipment left unused

—in some cases for years, exposing sensitive components to deterioration.

· Lack of inter-agency coordination

—between the Meteorology Department, Disaster Management Centre, and line ministries.

Some of the mistakes highlighted are incomprehensible. There is a mention that no soil test was carried out before the commencement of the construction of the tower. This led to construction halting after poor soil conditions were identified, requiring a shift of 10 to 15 meters from the original site. This resulted in further delays and cost overruns.

The equipment supplier had identified that construction work undertaken by a local contractor was not of acceptable quality for housing sensitive electronic equipment. No action had been taken to rectify these deficiencies. The audit report states, “It was observed that the delay in constructing the tower and the lack of proper quality were one of the main reasons for the failure of the project”.

In October 2012, when the supplier commenced installation, the work was soon abandoned after the vehicle carrying the heavy crane required to lift the radar equipment crashed down the mountain. The next attempt was made in October 2013, one year later. Although the equipment was installed, the system could not be operationalised because electronic connectivity was not provided (as stated in the audit report).

In 2015, following a UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services) inspection, it was determined that the equipment needed to be returned to the supplier because some sensitive electronic devices had been damaged due to long-term disuse, and a further 1.5 years had elapsed by 2017, when the equipment was finally returned to the supplier. In March 2018, the estimated repair cost was USD 1,095,935, which was deemed excessive, and the project was abandoned.

COPA proceedings

The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) discussed the radar project on August 10, 2023, and several press reports state that the GOSL incurred a loss of Rs. 78 million due to the project’s failure. This, I believe, is the cost of constructing the Tower. It is mentioned that Rs. 402 million had been spent on the radar system, of which Rs. 323 million was drawn from the trust fund established with WMO. It was also highlighted that approximately Rs. 8 million worth of equipment had been stolen and that the Police and the Bribery and Corruption Commission were investigating the matter.

JICA support and project stagnation

Despite the project’s failure with WMO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) entered into an agreement with GOSL on June 30, 2017 to install two Doppler Radar Systems in Puttalam and Pottuvil. JICA has pledged 2.5 billion Japanese yen (LKR 3.4 billion at the time) as a grant. It was envisaged that the project would be completed in 2021.

Once again, the perennial delays that afflict the GOSL and bureaucracy have resulted in the groundbreaking ceremony being held only in December 2024. The delay is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

The seven-year delay between the signing of the agreement and project commencement has led to significant cost increases, forcing JICA to limit the project to installing only one Doppler Radar system in Puttalam.

Impact of the missing radar during Ditwah

As I am not a meteorologist and do not wish to make a judgment on this, I have decided to include the statement issued by JICA after the groundbreaking ceremony on December 24, 2024.

“In partnership with the Department of Meteorology (DoM), JICA is spearheading the establishment of the Doppler Weather Radar Network in the Puttalam district, which can realize accurate weather observation and weather prediction based on the collected data by the radar. This initiative is a significant step in strengthening Sri Lanka’s improving its climate resilience including not only reducing risks of floods, landslides, and drought but also agriculture and fishery“.

Based on online research, a Doppler Weather Radar system is designed to observe weather systems in real time. While the technical details are complex, the system essentially provides localized, uptotheminute information on rainfall patterns, storm movements, and approaching severe weather. Countries worldwide rely on such systems to issue timely alerts for monsoons, tropical depressions, and cyclones. It is reported that India has invested in 30 Doppler radar systems, which have helped minimize the loss of life.

Without radar, Sri Lanka must rely primarily on satellite imagery and foreign meteorological centres, which cannot capture the finescale, rapidly changing weather patterns that often cause localized disasters here.

The general consensus is that, while no single system can prevent natural disasters, an operational Doppler Radar almost certainly would have strengthened Sri Lanka’s preparedness and reduced the extent of damage and loss.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s inability to commission a Doppler Radar system, despite nearly two decades of attempts, represents one of the most significant governance failures in the country’s disastermanagement history.

Audit findings, parliamentary oversight proceedings, and donor records all confirm the same troubling truth: Sri Lanka has spent public money, signed international agreements, received foreign assistance, and still has no operational radar. This raises a critical question: should those responsible for this prolonged failure be held legally accountable?

Now may not be the time to determine the extent to which the current government and bureaucrats failed the people. I believe an independent commission comprising foreign experts in disaster management from India and Japan should be appointed, maybe in six months, to identify failures in managing Cyclone Ditwah.

However, those who governed the country from 2007 to 2024 should be held accountable for their failures, and legal action should be pursued against the politicians and bureaucrats responsible for disaster management for their failure to implement the 2007 project with the WMO successfully.

Sri Lanka cannot afford another 18 years of delay. The time for action, transparency, and responsibility has arrived.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of any organization or institution with which the author is affiliated).

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoJetstar to launch Australia’s only low-cost direct flights to Sri Lanka, with fares from just $315^

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’