Features

Personal contacts with top Burgher cops and other Public Servants of 50-years ago

by Senior DIG (Rtd.) Edward Gunawardene

In recent weeks many interesting articles have appeared in the Sunday Island on the Burghers of Ceylon. The contributions by Godwin Perera, Laksman Ratnapala, A. J. Perera, Sumith de Silva and Manel Fonseka have rekindled in me memories of the many public figures of the Burgher community, particularly police officers at the time I joined the police in the late fifties of the last century. The mix-up in photos of Col. F. C. de Saram and Canon R. S. de Saram and the references to Burgher bits were indeed amusing.

When I joined the police, the induction process of new entrants to gazetted rank, required probationary ASPs to be introduced by appointment to senior public officers including the Governor General, Prime Minister, Chief Justice, Attorney General etc. As such, with my batchmates before long I was able to meet several amiable public servants of the Burgher community.

It is with a sense of nostalgia that I recall memories of these Burgher stalwarts. Not many days after I first met Justice M. C. Sansoni I had the pleasure of playing a game of billiards with him at the Police Officer’s Mess. In l the mid-seventies I came to know him better as I was the main witness before the Sansoni Commission inquiring in to the communal riots of 1977 in Trincomalee.

Attorney General Douglas Budd Jansze remains unforgettable. In a 1961 murder case well known as the Pathiraja JP murder case of Kurikotuwa in the Veyangoda police area, being ASP Gampaha, I was the chief investigator together with crown counsel G.P.S.de Silva, later chief justice, who was my Marrs Hallmate at Peradeniya, and Ranjith Abeysuriya met AG Budd Jansze and suggested that one of the suspects be made a Crown Witness. After a prolonged discussion the AG was of the view that a conviction could be obtained without such a move. After a lengthy trial at the Negombo Assizes the accused were acquitted. The defence team of lawyers consisted of G.G.Ponnambalam Senior, A.C.M.Ameer, Dicey Kanagaratnem; Nihal Jayawickrama and Asoka Obeysekara were assigned counsel. Daya Perera Senior Crown Counsel prosecuted. Although the case failed, I was especially commended by the IGP S.A.Dissanayake.

Budd Jansze, the true gentleman that he was sent for me and apologized to me for not taking my advise of making a suspect a Crown Witness. Such admirable senior officers have become a rarity today. Senior Burgher officers Messrs Neville Jansze, R.L.Arnolda, David Loos and Travis Ludowyk were extremely helpful when I had to learn treasury procedures. Francis Pietersz my classmate at St.Joseph’s College, who as the AGA Kalutara when I was at the police training school was of great assistance in the sustenance of the thousands of Tamil refugees who had flocked to the police training school during the 1958 communal riots. Pietersz, who is today my immediate neighbour at Battaramulla, remains a dear friend.

Anton Mc Heyzer is remembered as the GA Trincomalee who hosted the three probationary ASPs when they rode 1,000cc Harley Devidson motor bikes to Trinco as learners with Sub Inspector Dudley Von Haght as the instructor. Von Haght rode an 800cc Triumph Thunderbird with a booming beat. Mc Heyzer, the dedicated sports promoter, hosted us to lunch at the Welcombe Hotel.

Justice Percy Collin Thome , whom I had met with my friends Prof. Lyn Ludowyk and senior dons Doric de Souza and Ian Van den Driesen at the university faculty club invited me on several occasions to his apartment close to the Regal Cinema. At one of these dinners that were catered by Pilawoos I had the pleasure of meeting Justice E.F.N. Graetien, easily one of the foremost Burgher public figures of 20th century Ceylon. Two Burgher police officers that used to meet with this elite group of officers were Tommy Kelaart and R.A.Stork. More of them later.

As I reminisce about my Burgher colleagues of the police of the fifties, it is with much pleasure that I remember MLD Caspersz, one of the most senior public servants of the time. I had met him before I joined the police, during my early days in the police and also living in retirement. I met him first when I worked as a temporary clerk in the Food Control Department after sitting the university entrance exam in 1952. He was the Food Controller; and my immediate boss was another Burgher, Brendon Joachim, Asst. Food Controller. I came to know him better in 1959 when I had a three weeks assignment as the ASP Harbour as ASP Royden Vanderwall, the incumbent, was on overseas leave. On my second day in office, to my surprise, it was the Principal Collector of Customs, M.L.D. Caspersz himself that walked in to my room saying “Good Morning”. After a pleasant chat he told me that I as the ASP will also enjoy the powers of an Asst. Collector especially in the detection of customs offences.

In later years, I had the pleasure of meeting Mr and Mrs Caspersz on the south west breakwater. They were both keen anglers who got me too interested in this profitable hobby.

By the time I had completed my Divisional Training in the Colombo Division and the CID I had come to know the bulk of the senior gazetted officers of the police. The total number was about 70. Living in the officers mess on Brownrigg Road, befriending most of these officers was by no means difficult but costly. The mess was a pleasant meeting place with a not too expensive ‘watering hole’!

When I commenced police life at the Kalutara Training School there were three DIGs C.C.Dissanayake who was acting IGP, Sydney de Zoysa and Willem Leembruggen, two Gr 1 SP’s (present day SSPs) 17 SPs and 65 ASPs. Of the total of these officers over 25 were Burgher officers ranging from DIGs to ASPs.

In fairness to the Burgher community at this stage I wish to mention the names of some of Inspectors of Police who held key positions. Derrik Christofelsz was perhaps the only Chief Inspector. He was the respected court officer of the Colombo Chief Magistrate Court. This tall and imposing officer was highly regarded by even the senior lawyers of the Magistrate Court of the time; Merril Pereira, Charles Vethacan, A.Mahesan, R.L.N de Soyza and Manoharan Nagaraja to mention few. Derrik’s brother Hague Christofelsz was attached to the Batticaloa Divition. Eric Van den Driesen, Vernon Dickman, Anton Joachim, Mervin Serpanchy and Hubert Bagot were senior Burgher Inspectors on the verge of promotion to the rank of ASP. Bagot who was the chief horse-riding insructor and head of the Mounted Police Div. was an excellent horseman who had been in the Ceylon mounted squad at the Coronation. Inspector Eddie Gray, also an outstanding horseman and boxer, had just retired and was living in the Inspector’s quarters at Bambalapitiya opposite the Officers Mess.

In 1960 when I was ASP Gampaha I was fortunate to have Inspector Mike Schokman as the OIC of Mirigama. With Divulapitiya MP Lakshman Jayakkody, the junior Minister of Defence, the ASP Gampaha had no problems as Jayakkody and Schokman had been cricketing mates and friends at Trinty College. It must be said that the police suffered a great loss when this outstanding officer decided to emigrate before his promotion to gazetted rank.

Other Burghers of the Inspectorate that I remember who served under me in the early sixties were Lyn Taylor, Petersz, Rosairo of the Police Training School, Vernon Elias, ‘Sweety’ Weber, B.Stave my senior at St.Joseph’s an excellent hockey player, Batholomeuz, Eddie Buultjens, Fred Barthelot and Gerry Paul.

The last named was the conductor of the prestigious Police Band and was popularly referred to as the Band Master. His father too had been the first Ceylonese Police Band master. Inspector Gerry Paul was an outstanding musician. His proudest moment had been when Sir Malcom Sergeant, the conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, having listened to a special rendition of classical music by the Police Band had written in the Officer’s Visiting Book “Mr. Gerry Paul is without doubt one of the finest conductors in the East”

As mentioned earlier in this essay when I joined the police in early 1958 the total number of officers of the rank of ASP and above was about 70. Of this number over 25 were Burgher Officers ranging from DIGs to Probationary ASPs. Willem Leembruggen as DIG Range 3 was the most senior of these Burgher officers.

An experience I had with him in 1960 when I was ASP Chilaw is worth recalling. ‘Lemba’ as he was better known by the Junior Officers was to pay me a surprise visit one morning. Having stopped his jeep by the beach with a girlfriend inside he walked in to my office in white shorts and a white cloth hat. He looked a tourist. After saluting I offered my seat. Saying, “Thank you” he sat on a chair in front of my desk. He then politely offered me a cigarette and lit it before lighting his. When I was smoking and chatting with the DIG, HQI Opatha peeped in to the room and hurriedly left. All officers present were moving about in excitement. When ‘Lemba’ left after thanking me he did not want me to accompany him to the jeep. The story that went round Chilaw Police circles was that the young ASP was seated and smoking in front of the DIG! This is what the HQI had seen when he peeped into the room. Indeed, a perfect example of perception.

When I underwent training in the CID towards the end of 1958, the head of this important Division was David Pate who had been just appointed as a DIG about two months earlier. He was a gentleman to his fingertips.

One evening when I walked in to the Mess after a game of tennis I saw him seated in the veranda with a middle aged gentleman who very much resembled him. There was a bottle of Gordon’s gin on the table. As I passed them, saying “wait a minute” he introduced me to his father who was seated with him. The older Pate was the reputed racing correspondent of the ‘Observer’

Cecil Wambeek was the most senior of the SPs. As ASP Nugegoda I was fortunate to have him as my superior. The HQI was M.B.Werapitiya the elder of the well-known Werapitiya brothers. Blue eyed and handsome Wambeek was an excellent horseman. He insisted that I join him on horseback on the many gravel paths leading to Diyavanna in the Kotte area.

Another Burgher officer, high up in seniority, Richard Arndt, was the SP Headquarters in 1958. He was thorough with all the rules and regulations; and the entire civilian staff came under him. Practical in outlook he once told me ‘’Never be guided by the minutes made by subject clerks. Learn to make your own decisions and take responsibility for such decisions’’. An excellent swimmer be spent much of his leisure in the sea.

Karl Van Rooyen, Tommy Kelaart, H.K.Van den Driesen, Herbert Toussaint and Jamie Rosmale-Koch were all accomplished senior officers. Van Rooyen was the descendant of a Boer prisoner who had been banished for not taking the oath of allegiance to the King. As the SP Kandy he was held in very high esteem. Tommy Kalaart was an excellent cricketer. H.K. Van den Driesen who was SP Colombo was a tactful officers who had earned the confidence of Prime Minister Bandaranaike. Aubrey Collette, the respected cartoonist, caricatured him as Hari Kattaya (HK). Collette a Burgher of the class of Lionel Wendt and Eric Swan enjoyed a place of importance in the Ceylonese social scene.

A considerable percentage of the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) were Burghers. Having become friends with them primarily by associating with them at the Officer’s Mess, I not only remember their names, but also visualize their behavioural peculiarities.

Some of the names I can easily recall are Jack Van Sanden, Rex Hepponstall, I.D.M. Van Twest, R.A.Stork, Fred Brohier, Royden Vanderwall, Louis Potger, Fred Zimsen, Leonard Conderlag, H.G.Boudewyn, Fred De Saram, Alan Falmer Caldera, COS Orr and Ainsely Batholomeuz.

Fred Brohier was the second in command to Stanley Senanayake at the Police Training School. Prior to joining the Police he had been a RAF Pilot who had been awarded the Burma Medal. Van Twest was a national football administrator. R.A. Stork as the ASP Colombo West supervised my training at the Pettah Police Station. He was a national putt shot champion. Alan Flamer Caldera, if he was in the Mess, could be heard from Brownrigg Road. His pretty daughter, Jilska, was an outstanding national athlete.

Fred de Saram nick named ‘Kukul’ Saram claimed he was a Goigama Sinhalese. One of his daughters, Srimani, married Lalith Athulathmudali. When I married in 1966, ‘Kukul’ Saram in retirement was the banquet manager of the GOH. He laid out the best that the hotel could offer when he came to know that Governor General Gopallawa and Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake were to be the attesting witnesses.

Before I conclude I cannot help but mention Rear Admiral, Victor Hunter who was the head of the Navy whom I met under fortuitous circumstances. On my way to Police Headquarters one morning I heard on police radio clatter that a navy rating guarding Radio Ceylon had shot himself dead inside the sentry box. An investigation was on and Rear Admiral Hunter was there as an observer. Being the senior officer present as an ASP, I got chatting with him. He casually asked me ‘’why do you think this fellow committed suicide?’’ My reply was ‘’A young man joins the Navy to see the world and not to stand in a sentry box day in and day out”! Hunter smiled in agreement and said ‘’you have a similar problem. Several young policemen wanting to join the Navy interviewed by me have confessed that they hated manning the gates of residences of politicians and saluting even family members and visitors!’’

Hunter and B.R.Heyn were perhaps the only burghers to head the Navy and Army respectively in post-independence Sri Lanka.

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Features6 days ago

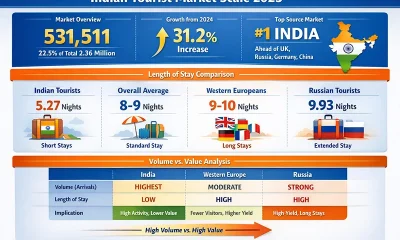

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans