Opinion

Numbers behind different COVID-19 vaccines

By M. C. M. Iqbal

The vaccines against COVID-19, available today, are based on different strategies and come with different numbers to indicate their performance. Many of us wish to know if one vaccine is better than the other. Two concepts underlying the performance of the vaccines are efficacy and effectiveness. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has an efficacy of 95 percent, the Moderna Vaccine is 94.5 percent and the Russian made Sputnik vaccine is over 90 percent. Does this mean some vaccines are better than the other? The short answer is no. All the approved vaccines are equally good. So, let us look at what these numbers mean.

These numbers refer to statistical calculations to interpret the results of vaccination trials conducted by the manufacturers of vaccines, following a prescribed format. The method of calculation was developed over 100 years ago by two statisticians, who published their results in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1915. They, Major Greenwood (Major is his first name and not a military title) and Udny Yule, were tasked with interpreting the results of immunization of British soldiers against typhoid and cholera, who were fighting in different regions of Europe and Asia favourable to the development of cholera epidemics. In a paper stretching over 82 pages, the authors developed the theoretical and mathematical background for calculating the efficacy of vaccines.

This article seeks to explain to the lay reader what these numbers imply and to bring out the differences between efficacy and effectiveness of a vaccine.

Efficacy and effectiveness

At first sight these two terms appear to be synonyms. However, in the world of vaccines and medicine, these two terms are not the same. Efficacy of a vaccine is how it performs under ideal and controlled conditions in a clinical trial (see below). During clinical trials, the outcome of vaccination is compared between a group of vaccinated people and another group given an inactive form of the vaccine (called a placebo). The effectiveness of a vaccine is how the vaccine performs in the real world – that is after the vaccine is approved by the regulatory agencies and you and I are vaccinated.

The efficacy of a vaccine is measured by the manufacturers under ideal conditions in a clinical trial where criteria are specified for selecting and excluding volunteers. These criteria are usually age groups, gender, ethnicity, geographical location and socio-economic standing. If the criteria are specific, then the effects of the vaccine or drug would not be applicable across the population. For example, if the COVID-19 vaccines are not tested on children below 18 years, then the approved vaccine cannot be used on children.

The effectiveness of a drug or vaccine is a measure of how well the drug or vaccine performs in real life, in a diverse population: Fitness geeks and couch potatoes, housewives and nurses, and farmers and office workers. Effectiveness is of relevance to the medical community and healthcare authorities who are treating the patients. Thus, studies on effectiveness would look at to what extent the vaccine is beneficial to the patient to prevent infection.

One may ask, why not simply look at the effectiveness of the vaccine? This is because if the participants in an initial trial of the vaccine are not carefully controlled, then it is difficult to interpret the outcome of the trial. We have many characteristics, which can potentially interfere with the outcome of a trial testing a vaccine. The person volunteering for the trial could be young or old, pregnant or not, a marathon runner or an average person and smoker or non-smoker. Thus, the volunteers selected for the trials are very similar within their groups with many criteria to exclude persons who could confuse the results (for example, an unhealthy person with other diseases would be excluded).

Efficacy of a vaccine asks the question ‘Does the vaccine work under ideal conditions?’ On the other hand, a study on the effectiveness of the same vaccine asks the question ‘Does vaccination work in the real world?’

Clinical trials

Under normal circumstances, vaccines take many years of research and testing to be approved. The COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented, and pharmaceutical companies embarked on a race against time to produce safe and effective vaccines. The genome of this coronavirus, which was discovered by Chinese scientists, in January 2020, was a major contribution to the development of the vaccines. At the moment there are 94 vaccines being tested on humans in clinical trials, 32 of which have reached the final stage of Phase 3 testing.

To obtain approval for a vaccine, the vaccine manufacturers go through a prescribed process to ensure that the vaccine is safe. All the countries have a national drug approval agency, who should approve the use of a drug or vaccine in that country. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States is an important regulatory agency, which has stringent criteria to approve medicines and drugs. In Sri Lanka, it is the National Medicines Regulatory Authority. COVID-19 vaccines are also assessed and approved by the WHO.

Initially, the vaccine is tested on cells in the laboratory and then given to animals, usually mice or monkeys. After this, if the mice or monkeys are happy, human volunteers are recruited to conduct the clinical trials, which is done in three phases. In the first phase, the vaccine is tested on a small group of people to determine the safety, dosage and ability to stimulate our immune system. If this is confirmed, the vaccine then moves into the Phase 2 stage where the safety of the vaccine is tested on hundreds of people who are split into different groups. Once these trials are successful, the vaccine moves to the final Phase 3 trials. Here thousands of people are recruited as volunteers. For the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine there were over 40,000 volunteers, above the age of 16, from different countries. This trial is more comprehensive, with the volunteers belonging to different age groups, physical fitness, ethnicities and geographical locations. The volunteers are divided into two groups. One group gets the real vaccine while the other group gets a fake vaccine or placebo (the syringe has just water). The volunteers would not know if he/she is getting the vaccine or a placebo and neither do the nurses and doctors giving the vaccine. This is called a double-blind clinical trial. Thus, no one knows, except those conducting the trial, who was vaccinated with what.

After some time, the volunteers, who fell sick with the coronavirus, are PCR tested to confirm if they are COVID-19 positive. The scientists will be on the lookout for any side effects of the vaccine; if they find any cause for concern the trial can be stopped temporarily to conduct investigations and remedy the problem. If the scientists are not satisfied, the trial would be abandoned. Once the results are in, the calculations are done, and all the details are submitted to the regulating authorities. The regulators would ask the manufacturers more questions and once they are satisfied, approval is given to manufacture and market the vaccine. To accelerate the process, such as now during the COVID-19 crises, Phase 1 and 2 may be combined and run in parallel.

Calculating efficacy

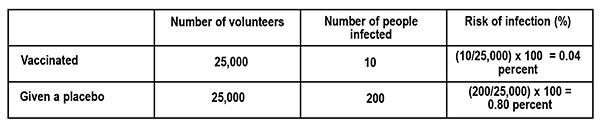

The calculations involved are quite simple once the data is collected. Let us assume that 50,000 volunteers were recruited for the vaccination trial. Half were given the vaccine and the other half a placebo. Let us assume that of the 25,000 who received the vaccine, 10 persons were infected, and of the other 25,000 who received the placebo, 200 were infected. Although the numbers of people infected are small, those in the placebo group are 20 times larger (see Table). The researchers are concerned with the relative risk between the groups. This is called the efficacy of the vaccine.

The risk of infection is calculated as follows.

What is the difference in the risk of infection between the vaccinated group and those who got the placebo? From the table this is, 0.80 percent – 0.04 percent = 0.76 percent.

Thus, the vaccine reduced the risk of infection by 0.76 percent, which looks quite small. This is what would happen if we are vaccinated. To understand this in terms of the risk of infection, if none were vaccinated, we look at the ratio of the Reduction in Infection (0.76 percent) to the Risk of infection (0.80 percent – those who got the fake vaccine). This is the Vaccine Efficacy (VE).

VE percent = Reduction in infection ÷ Risk of infection = 0.76 ÷ 0.80 = 95 percent

If this is still confusing, let us see what it means in a population of 100,000 persons who are vaccinated with a vaccine of 95 percent efficacy, and exposed to the virus. From the table above, the risk of infection for the vaccinated population is 0.04 percent, which translates to 40 persons (0.04 percent x 100,000). That is, we can expect that 40 persons would fall ill with an infection by the coronavirus and the rest of the vaccinated people may not develop an infection at all or develop an asymptomatic infection (you are infected but do not show symptoms) or get a mild disease.

(This example of calculating Vaccine Efficacy is adapted from an article by Dashiell Young-Saver in the New York Times of December 13, 2020, where the above calculation is explained in detail for students.)

What does efficacy mean?

The efficacy of a vaccine refers to two aspects. The first is how many of us are protected by the vaccine if we are exposed to the virus; this is given by the percentage. The vaccine also refers to different disease conditions it is capable of preventing. This could be causing an infection, mild disease, severe disease, hospitalisation, or death. This information can be found if one looks carefully at the statements issued by the vaccine manufacturer and regulatory agencies. For example, the statement by Pfizer-BioNTech states: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, BNT162b2, was 91.3 percent effective against COVID-19 (symptomatic cases of COVID-19), measured seven days through up to six months after the second dose. The vaccine was 100 percent effective against severe disease as defined by the US centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 95.3 percent effective against severe disease as defined by the US FDA.

The efficacy of a vaccine (VE) is the relative reduction of being infected, if we are vaccinated, compared to the placebo or unvaccinated group. If the vaccine is perfect, then the risk of being infected is totally eliminated, so that VE = 1 or it is 100 percent. On the other hand, if there is no difference in the number of people infected between the two groups, the vaccine has no efficacy, or it is zero. Even with a perfect vaccine, our capacity to acquire an infection is determined by our age, health and immunity status.

In short, efficacy is a statistical measurement based on clinical trials of the vaccine’s ability to prevent infection. The volunteers taking part in the trials are not a perfect sample or representative of the real world (for example, children and sick people do not take part). Is there a lower limit for the efficacy of a vaccine to be accepted? Under the present circumstances, the FDA said it would consider granting emergency approval if the vaccines showed even 50 percent efficacy; the vaccines that have received approval now show an efficacy of over 90 percent.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the vaccine tells us how well the vaccine is performing among the population, in the real world, to prevent infection. The effectiveness of the vaccine depends on the impact it makes on society. After vaccination our immune system is primed to combat the coronavirus, reducing the multiplication of the virus in our body. This will gradually slow down the spread of the virus as more and more people are vaccinated. In other words, it is important that most if not all the people are vaccinated to have a large impact on the spread of the virus in society. Good examples are the smallpox vaccine, which completely eliminated the smallpox virus, and the polio vaccine, which has almost wiped out the polio virus except for a few small pockets in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Africa. Thus, the effectiveness of a vaccine looks at the medical and societal importance of the outcome.

Here is the above in a nutshell. The percentage numbers given with a vaccine refers to its efficacy – its ability to prevent an infection developing into a serious condition, determined under controlled clinical trials. Vaccines do not prevent infection – they prevent the infection from developing into a severe disease. Once we are vaccinated, our immune system is activated. If we are infected by the coronavirus, the virus has a small window of time to multiply, before it is eliminated by our immune system. This means we can release virus particles from our body, but much less than if we were not vaccinated. The message is we should get vaccinated with the first available vaccine and still wear our masks when going outside, even if we are vaccinated. The chances of ending up in a hospital is low and the chances of ending up in the ICU is very low. There is always a chance.

‘Tis impossible to be sure of anything but Death and Taxes (Christopher Bullock, 1716).

(M.C.M. Iqbal is Associate Research professor, Plant and Environmental Science, National Institute of Fundamental Studies, Hanthane Road, Kandy, and can be reached at iqbal.mo@nifs.ac.lk)

References

Zimmer, C. New York Times Nov. 20, 2020. Two companies say their vaccines are 95 percent effective. What does that mean?

Haelle,T. Association of Health Care Journalists. October 22, 2020. Know the nuances of vaccine efficacy when covering Covid-19 trials. https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2020/10/know-the-nuances-of-vaccine-efficacy-when-covering-covid-19-vaccine-trials/

Greenwood, M., & Yule, G. U. (1915). The Statistics of Anti-typhoid and Anti-cholera Inoculations, and the Interpretation of such Statistics in general. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 8 (Sect Epidemiol State Med), 113–194.

Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.fda.gov/media/139638/download

Opinion

Why so unbuddhist?

Hardly a week goes by, when someone in this country does not preach to us about the great, long lasting and noble nature of the culture of the Sinhala Buddhist people. Some Sundays, it is a Catholic priest that sings the virtues of Buddhist culture. Some eminent university professor, not necessarily Buddhist, almost weekly in this newspaper, extols the superiority of Buddhist values in our society. Some 70 percent of the population in this society, at Census, claim that they are Buddhist in religion. They are all capped by that loud statement in dhammacakka pavattana sutta, commonly believed to have been spoken by the Buddha to his five colleagues, when all of them were seeking release from unsatisfactory state of being:

‘….jati pi dukkha jara pi dukkha maranam pi dukkham yam pi…. sankittena…. ‘

If birth (‘jati’) is a matter of sorrow, why celebrate birth? Not just about 2,600 years ago but today, in distant port city Colombo? Why gaba perahara to celebrate conception? Why do bhikkhu, most prominent in this community, celebrate their 75th birthday on a grand scale? A commentator reported that the Buddha said (…ayam antima jati natthi idani punabbhavo – this is my last birth and there shall be no rebirth). They should rather contemplate on jati pi dukkha and anicca (subject to change) and seek nibbana, as they invariably admonish their listeners (savaka) to do several times a week. (Incidentally, Buddhists acquire knowledge by listening to bhanaka. Hence savaka and bhanaka.) The incongruity of bhikkhu who preach jati pi duklkha and then go to celebrate their 65th birthday is thunderous.

For all this, we are one of the most violent societies in the world: during the first 15 days of this year (2026), there has been more one murder a day, and just yesterday (13 February) a youngish lawyer and his wife were gunned down as they shopped in the neighbourhood of the Headquarters of the army. In 2022, the government of this country declared to the rest of the world that it could not pay back debt it owed to the rest of the world, mostly because those that governed us plundered the wealth of the governed. For more than two decades now, it has been a public secret that politicians, bureaucrats, policemen and school teachers, in varying degrees of culpability, plunder the wealth of people in this country. We have that information on the authority of a former President of the Republic. Politicians who held the highest level of responsibility in government, all Buddhist, not only plundered the wealth of its citizens but also transferred that wealth overseas for exclusive use by themselves and their progeny and the temporary use of the host nation. So much for the admonition, ‘raja bhavatu dhammiko’ (may the king-rulers- be righteous). It is not uncommon for politicians anywhere to lie occasionally but ours speak the truth only more parsimoniously than they spend the wealth they plundered from the public. The language spoken in parliament is so foul (parusa vaca) that galleries are closed to the public lest school children adopt that ‘unparliamentary’ language, ironically spoken in parliament. If someone parses the spoken and written word in our society, there is every likelihood that he would find that rumour (pisuna vaca) is the currency of the realm. Radio, television and electronic media have only created massive markets for lies (musa vada), rumour (pisuna vaca), foul language (parusa vaca) and idle chatter (samppampalapa). To assure yourself that this is true, listen, if you can bear with it, newscasts on television, sit in the gallery of Parliament or even read some latterday novels. There generally was much beauty in what Wickremasinghe, Munidasa, Tennakone, G. B. Senanayake, Sarachchandra and Amarasekara wrote. All that beauty has been buried with them. A vile pidgin thrives.

Although the fatuous chatter of politicians about financial and educational hubs in this country have wafted away leaving a foul smell, it has not taken long for this society to graduate into a narcotics hub. In 1975, there was the occasional ganja user and he was a marginal figure who in the evenings, faded into the dusk. Fifty years later, narcotics users are kingpins of crime, financiers and close friends of leading politicians and otherwise shakers and movers. Distilleries are among the most profitable enterprises and leading tax payers and defaulters in the country (Tax default 8 billion rupees as of 2026). There was at least one distillery owner who was a leading politician and a powerful minister in a long ruling government. Politicians in public office recruited and maintained the loyalty to the party by issuing recruits lucrative bar licences. Alcoholic drinks (sura pana) are a libation offered freely to gods that hold sway over voters. There are innuendos that strong men, not wholly lay, are not immune from seeking pleasures in alcohol. It is well known that many celibate religious leaders wallow in comfort on intricately carved ebony or satin wood furniture, on uccasayana, mahasayana, wearing robes made of comforting silk. They do not quite observe the precept to avoid seeking excessive pleasures (kamasukhallikanuyogo). These simple rules of ethical behaviour laid down in panca sila are so commonly denied in the everyday life of Buddhists in this country, that one wonders what guides them in that arduous journey, in samsara. I heard on TV a senior bhikkhu say that bhikkhu sangha strives to raise persons disciplined by panca sila. Evidently, they have failed.

So, it transpires that there is one Buddhism in the books and another in practice. Inquiries into the Buddhist writings are mainly the work of historians and into religion in practice, the work of sociologists and anthropologists. Many books have been written and many, many more speeches (bana) delivered on the religion in the books. However, very, very little is known about the religion daily practised. Yes, there are a few books and papers written in English by cultural anthropologists. Perhaps we know more about yakku natanava, yakun natanava than we know about Buddhism is practised in this country. There was an event in Colombo where some archaeological findings, identified as dhatu (relics), were exhibited. Festivals of that nature and on a grander scale are a monthly regular feature of popular Buddhism. How do they fit in with the religion in the books? Or does that not matter? Never the twain shall meet.

by Usvatte-aratchi

Opinion

Hippocratic oath and GMOA

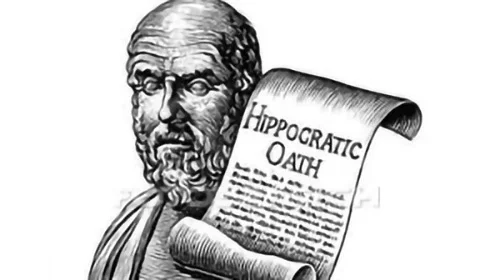

Almost all government members of the GMOA (the Government Medical Officers’ Association). Before joining the GMOA Doctors must obtain registration with Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC) to practice medicine. This registration is obtained after completing the medical studies in Sri Lanka and completing internship.

The SLMC conducts an Examination for Registration to Practise Medicine in Sri Lanka (ERPM) – (Formerly Act 16 in conjunction with the University Grants Commission (UGC), which the foreign graduates must pass. Then only they can obtain registration with SLMC.

When obtaining registration there are a few steps to follow on the as stated in the “

GUIDELINES ON ETHICAL CONDUCT FOR MEDICAL & DENTAL PRACTITIONERS REGISTERED WITH THE SRI LANKA MEDICAL COUNCIL” This was approved in July 2009, and I believe is current at the time of writing this note. To practice medicine, one must obtain registration with the SLMC and complete the oath formality. For those interested in reading it on the web, the reference is as follows.

https://slmc.gov.lk/images/PDF_Main_Site/EthicalConduct2021-12.pdf

I checked this document to find the Hippocratic Oath details. They are noted on page 5. The pages 6 & 7 provide the draft oath form that every Doctor must complete with his/her details. Oath must be administered by

the Registrar/Asst. Registrar/President/ Vice President or Designated Member of the Sri Lanka Medical Council and signed by the Doctor.

Now I wish to quote the details of the oath.

I solemnly pledge myself to dedicate my life to the service of humanity;

The health of my patient will be my primary consideration and I will not use my profession for exploitation and abuse of my patient;

I will practice my profession with conscience, dignity, integrity and honesty;

I will respect the secrets which are confided in me, even after the patient has died;

I will give to my teachers the respect and gratitude, which is their due;

I will maintain by all the means in my power, the honour and noble traditions of the medical profession;

I will not permit considerations of religion, nationality, race, party politics, caste or social standing to intervene between my duty and my patient;

I wish to ask the GMOA officials, when they engage in strike action, whether they still comply with the oath or violate any part of the oath that even they themselves have taken when they obtained registration from the SLMC to practise medicine.

Hemal Perera

Opinion

Where nature dared judges hid

Dr. Lesego the Surgical Registrar from Lesotho who did the on-call shift with me that night in the sleepy London hospital said a lot more than what I wrote last time. I did not want to weaken the thrust of the last narrative which was a bellyful for the legal fraternity of south east Asia and Africa.

Lesego begins, voice steady and reflective, “You know… he said, in my father’s case, the land next to Maseru mayor’s sunflower oil mill was prime land. The mayor wanted it. My father refused to sell. That refusal set the stage for everything that followed.

Two families lived there under my dad’s kindness. First was a middle-aged man, whose descendants still remain. The other was an old destitute woman. My father gave her timber, wattle, cement, Cadjan, everything free, to build her hut. She lived peacefully for two years. Then having reconciled with her once estranged daughter wanted to leave.

She came to my father asking for money for the house. He said: ‘I gave you everything free. You lived there for two years completely free and benefitting from the produce too. And now you ask for money? Not a cent.’ In hindsight, that refusal was harsh. It opened the door for plunderers. The old lady ‘sold’ the hut to Pule, the mayor’s decoy. Soon, Pule and his fellow compatriots, were to chase my father away while he was supervising the harvesting of sunflowers.

My father went to court in September 1962, naming Thasoema, the mayor, his Chief clerk, and the trespassers as respondents. The injunction faltered for want of an affidavit, and under a degree of compulsion by the judge and the attending lawyers, my father agreed to an interim settlement of giving away the aggressors total possession with the proviso that they would pay the damages once the court culminates the case in his favour. This was the only practical alternative to sharing the possession with the adversaries.

From the very beginning, the dismissals and flimsy rulings bore the fingerprints of extra‑judicial mayoral influence. Judges leaned on technicalities, not justice. They hid behind minutiae.

Then nature intervened. Thasoema, the mayor, hale and hearty, died suddenly of what looked like choking on coconut sap which later turned out to be a heart attack. His son Teboho inherited the case. Months later, the Chief clerk also died of a massive heart attack, and his son took his place. Even Teboho, the mayor’s young son of 30 years died, during a routine appendectomy, when the breathing tube was wrongly placed in his gullet.

About fifteen years into the case, another blow fell. A 45‑year‑old judge, who had ruled that ‘prescription was obvious at a glance, while adverse possession was being contested in court all the time, died within weeks of his judgment, struck down by a massive heart attack.

After that, the case dragged on for decades, yo‑yoing between district and appeal courts. Judges no longer died untimely deaths, but the rulings continued to twist and delay. My father’s deeds were clear: the land bought by his brother in 1933, sold to him in 1936, uninterrupted possession for 26 years. Yet the courts delayed, twisted, and denied.

Finally, in 2006, the District Court ruled in his favour embodying every detail why it was delivering such a judgement. It was a comprehensive judgement which covered all areas in question. In 2015, the Appeal Court confirmed it, his job being easy because of the depth the DC judge had gone in to. But in October 2024, the Supreme Court gave an outrageously insane judgment against him. How? I do not know. I hope the judge is in good health, my friend said sarcastically.

Lesego paused, his voice heavy with irony “Where nature dared, judges hid. And that is the truth of my father’s case.”

Dr.M.M.Janapriya

UK

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction