Features

NPP govt., a patchwork of ideological differences, bound to suffer splits – FSP

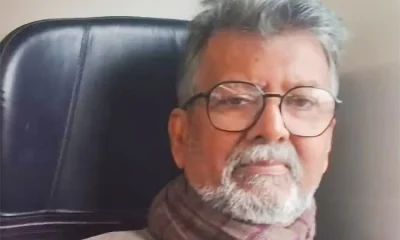

by Saman Indrajith

Education Secretary of the Frontline Socialist Party, Pubudu Jagoda, has expressed skepticism about the government’s ability to overcome the country’s pressing economic challenges.

In an interview with The Island, Jagoda highlights the inherent divisions within the JVP/NPP coalition, which, he believes, are bound to hinder its ability to provide meaningful relief to the public.

“The government is a patchwork of ideological contradictions,” Jagoda says. “It includes remnants of the old JVP cadre who advocate socialist solutions for economic problems. Alongside them are newer social democrats whose views often clash with the socialist stance. Adding to this complexity are neoliberals who align with Ranil Wickremesinghe’s policies but reject him personally, and a faction of nationalists—many of whom were part of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s Viyath Maga initiative before joining the NPP.”

Jagoda says that this diversity of perspectives has resulted in an inability to present a cohesive strategy for addressing the country’s economic woes. “This collection of divergent views struggles to formulate practical solutions for the people’s problems.”

Jagoda is of the view that the government’s current approach relies heavily on rhetoric around anti-corruption initiatives and promises of reforming the political culture. While these efforts may garner short-term support, they lack the capacity to address the more immediate issues faced by the population. “There are limits to how far you can go with slogans about changing the political culture. These initiatives cannot put food on people’s tables,” he said.

Excerpts of the interview:

Q: What is your assessment of the current situation in Sri Lanka?

A: The global economy has faced numerous crises over the years, from time to time. In the late 19th century, the 1920s, and 1973, significant economic downturns came into being. Historically, these crises have been characterised by fluctuating trends, often described using the shapes of English letters—V-shaped, U-shaped, and W-shaped—to denote the pattern of economic recovery and recession. For example, the 1973 crisis was V-shaped, while the 1927 crisis exhibited a W-shaped recovery. However, the global economic crisis of 2008 defied such conventional classifications. Initially described as L-shaped due to a sharp decline followed by prolonged stagnation, it later evolved into a pattern resembling a staircase cross-section. Economists now predict a further decline in 2025 and 2026, signifying a fast-collapsing global economy.

Economists argue that addressing the economic crisis requires a comprehensive strategy to manage external interventions by superpowers and to protect national interests. However, opposition parties, including the NPP and SJB, have failed to articulate clear economic policies. Their manifestos are technocratic and lack detailed strategies for addressing issues such as the debt crisis, state revenue challenges, foreign currency shortages, and a coherent development plan.

The government’s mandate, though significant in the parliamentary election, lacks a unified vision.

Sri Lanka faces three key economic policy challenges: the first one is continuation of IMF-driven policies. Will the NPP Government continue with the IMF’s structural adjustment programmes? The second is about managing superpower interventions: Can this government leverage its mandate to negotiate more favourable terms with global powers? The third is about addressing public welfare: Will the government prioritise economic relief for citizens or continue to favour corporate elites under the guise of political reform?

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis manifests starkly in rising poverty and malnutrition. Statistics reveal that 25% of families rely on financial support from neighbors and relatives, while 61% have reduced their food consumption. Child malnutrition rates have soared to 26%, levels previously associated with countries like Ethiopia and Somalia in the 1990s.

The government’s inability to articulate a clear economic vision and its reliance on neoliberal reforms risk deepening the crisis.

Q: What is the FSP going to do about it?

A: We advocate for an economic plan that provides an alternative to the IMF programme. We emphasise the importance of a foreign policy that protects Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and shields its people from the geostrategic invasions of powers like the US and India. Furthermore, we want the inequities created by a top corporate elite that benefited disproportionately from the previous regime’s economic policies addressed. Our position has consistently been that this elite should bear a fair share of the tax burden to provide relief to the people. These three pillars formed the foundation of our political campaign.

Looking ahead, we believe the most critical aspects will continue to revolve around these priorities, the first of them is opposition to the IMF programme. We challenge its long-term implications on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and economy. Then the issue of geostrategic independence. We advocate for a foreign policy that avoids subjugation to major powers. Third aspect is about equitable Taxation. We demand ensuring that economic policies benefit the majority rather than a privileged few.

As public frustration with the government grows, there is a real danger that people may revert to supporting extreme-right factions responsible for Sri Lanka’s economic turmoil. This could include figures like Ranil Wickremesinghe, members of the SJB, the Mahinda Rajapaksa camp, or even more regressive alternatives. History teaches us that severe economic crises often lead to two potential outcomes: revolutions/military coups or the rise of far-right fascist governments. Sri Lanka is no exception to this historical pattern.

If the current trajectory continues, new leaders could emerge from outside the existing political framework, replacing figures such as Ranil Wickremesinghe, Sajith Premadasa, or Namal Rajapaksa. Alternatively, the country could face a revolution or even a military coup. Superpowers are unlikely to oppose such outcomes, as these scenarios could align with their strategic interests and facilitate their agendas.

Recognising these risks, we are focused on preventing a sudden collapse of the government. While criticising the IMF programme and the restructuring of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs), we have taken proactive steps to offer alternatives. For instance, we submitted a detailed 13-page document outlining the dangers of the IMF programme and proposing alternative solutions. Recently, we provided 22 proposals for the national budget, reaffirming our commitment to constructive engagement rather than mere criticism.

Despite our efforts, the government has ignored these suggestions, offering no response or acknowledgment. Nevertheless, we see it as our responsibility to propose solutions and advocate for change. If the government continues on its current path, failure seems inevitable, leading to heightened public frustration.

In such a context, our primary focus is to create a political space that prevents the public from being pushed toward far-right factions or fascist military-style governance. To achieve this, we are engaging with leftist and progressive elements within the democratic framework. In the meantime, we are utilising platforms like the People’s Struggle to unite individuals and organisations against the potential rise of far-right authoritarianism.

This initiative seeks to build a broad coalition capable of resisting such a shift while advocating for a just and equitable alternative. We understand that this cannot be achieved by our party alone, so we are collaborating with other progressive forces to strengthen this movement.

Our efforts are directed toward preventing a political and economic regression in Sri Lanka. By uniting progressive forces and presenting clear alternatives, we aim to address the root causes of the crisis while protecting the nation from the threats of authoritarianism and economic subjugation.

Q: How would you interpret the Joint Statement issued by India and Sri Lanka following President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s visit?

A: We must acknowledge the geopolitical reality that India is both Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour and the regional superpower. It is inevitable that Sri Lanka must work with India while being mindful of her strategic and economic interests. However, this does not mean that we must relinquish our sovereignty, independence, or national dignity. A balance is both possible and necessary.

For instance, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s assurance that Sri Lanka would not allow its territory to be used against India’s security interests was, while prudent in principle, perhaps an over-commitment in execution. Safeguarding India’s security concerns is one thing but providing explicit commitments risks undermining our flexibility and sovereignty. It is a self-imposed limitation that could have been avoided.

Similarly, the joint statement’s commitments to land connectivity, an integrated oil pipeline, and a shared electricity grid raise serious concerns. These projects are not without precedent in the region, and the experiences of other nations connected to India offer cautionary lessons. Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh all face significant challenges arising from their direct land links with India. Sri Lanka’s geographical separation by sea has so far shielded it from similar vulnerabilities, and it would be unwise to jeopardise this advantage without thorough deliberation.

The proposed electricity grid integration is another contentious issue. Nations like Bangladesh, which are already connected to India’s electricity grid, are formulating exit strategies due to reliability and sovereignty concerns. For instance, Bangladesh faced prolonged power cuts when it failed to settle bills with India. Similarly, Nepal has been unable to fully exploit its hydropower potential because of obligations under agreements with India. Sri Lanka, with over a century of independent electricity production and potential for future self-sufficiency, has no engineering necessity to integrate its grid with India. Such a move appears driven more by political than practical considerations.

The oil pipeline and refinery agreements also warrant scrutiny. Historically, Sri Lanka has imported crude oil for domestic refining, with plans to upgrade facilities like the Sapugaskanda refinery to produce and export diesel and petrol, emulating Singapore. However, recent agreements have seen the handover of strategic assets, including Trincomalee’s oil tanks and the operation of local petrol stations, to Indian entities. Furthermore, the proposed monopoly on LNG supply by an Indian company undermines Sri Lanka’s ability to procure competitively priced LNG from global markets.

These agreements are reportedly still at the “in-principle” stage, but the government’s failure to consult parliament or public forums before committing to such significant undertakings raises serious concerns. Instead of deferring to agreements made by former President Ranil Wickremesinghe, whose policies were widely rejected in elections, the current administration should assert its mandate and demand reconsideration of these commitments.

The issue of awarding the digital national ID project to an Indian company further highlights the erosion of sovereignty. In an era where data is as critical as military assets, granting access to the biometric and personal data of 22 million Sri Lankans to a foreign entity is a grave risk. The tender process itself has been controversial, with conditions favoring only Indian companies and the tender notice published exclusively in Indian newspapers. This lack of transparency and favoritism raises alarms about national security and accountability.

Examples from other nations further underline the dangers of such agreements. In Kenya, the same Indian company involved in Sri Lanka’s digital ID project was banned after allegations of data fraud. Despite this, the Sri Lankan government has persisted with plans that effectively outsource national security data to a foreign entity, undermining the country’s sovereignty.

While Sri Lanka’s size and economic vulnerability necessitate diplomatic tact, these factors do not justify subservience to any foreign power. The President’s visit to India and the commitments made during the visit failed to uphold the dignity and independence of Sri Lanka. It is imperative that our leaders adopt a more balanced approach that safeguards national sovereignty while engaging constructively with India.

Q: How would you comment on the President’s scheduled visit to China?

A: The geopolitical scene has evolved significantly since the Cold War era, transforming international relations into a complex interplay of economic, political, and military interests. Unlike the binary divisions of the past, where nations were clearly aligned with one of two superpowers, today’s global politics involves multifaceted alliances that often overlap and conflict.

For instance, India, which historically aligned with the USSR, now pursues multiple roles. Economically, India collaborates with China and Russia within BRICS, promoting de-dollarization. However, militarily, India partners with the U.S. and other QUAD nations, positioning itself against Chinese regional dominance. Similarly, China has shifted its foreign policy from rigid ideological stances to pragmatic engagement, often accommodating regional superpowers’ roles in their respective spheres of influence.

In this context, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s upcoming visit to China is unlikely to yield significant pushback against the commitments made to India. China is more likely to seek reciprocal agreements, such as securing concessions in Hambantota or other strategic locations, rather than urging Sri Lanka to reject Indian interests outright. This reflects a broader Chinese strategy of coexistence with other regional powers while pursuing its own strategic and economic goals.

A case in point is China’s stance on Sri Lanka’s IMF programme. Unlike during the Cold War, when China might have opposed Western-led financial restructuring, it now focuses on securing a foothold within those frameworks. For example, if Sri Lanka privatizes state-owned entities like the CEB, China’s concern would not be with the principle of privatization but with acquiring a significant stake in those assets.

The lifting of the moratorium on research vessels in Sri Lankan waters exemplifies the government’s precarious balancing act. Allowing both Indian and Chinese vessels to conduct ocean floor mapping may appear to appease both powers, but it risks antagonizing one or the other, depending on the strategic implications of the research findings. The government might view this as a strategy to placate China following the President’s visit to India, but such concessions only deepen the geopolitical entanglement.

Instead of succumbing to these pressures, Sri Lanka should revisit and reaffirm its historical commitment to neutrality in the Indian Ocean, as embodied in the 1972 UN resolution declaring the region a Zone of Peace. This resolution, co-sponsored by Sri Lanka and India, explicitly seeks to prevent military and economically motivated agreements with indirect military implications among Indian Ocean littoral states. By invoking this resolution, Sri Lanka could resist external pressures without directly antagonizing powerful nations.

The government’s current approach, of attempting to “give a little to everyone,” is fraught with risk. It creates the perception of a nation willing to compromise its sovereignty for short-term diplomatic gains. Such policies can lead to long-term strategic vulnerabilities, as seen with the lifting of the research vessel moratorium and the transactional diplomacy of balancing Chinese and Indian interests.

The broader concern is that Sri Lanka’s vulnerability, compounded by economic challenges, could make it a flashpoint in escalating global tensions. Any future conflict, potentially involving advanced ballistic missile systems, AI-driven warfare, and nuclear capabilities, would have catastrophic consequences for small nations like Sri Lanka.

While the government justifies its actions as necessary for an economically bankrupt nation, we believe that there remains space to assert Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and protect its long-term interests. Diplomacy should not equate to submission, and economic hardship must not justify policies that undermine national security and dignity. Instead, the leadership must tread carefully, adopting a principled approach that balances strategic interests while preserving the country’s independence.

Q: How do you view the Aragalaya protests now after years of their end?

A: The Aragalaya emerged as a powerful expression of public frustration, driven predominantly by economic pressures. For many Sri Lankans, the tipping point was the failure of Gotabaya Rajapaksa to provide relief during a devastating economic crisis. The sense of betrayal was especially acute among those who had voted for him in 2019, such as in Kaduwela, where Gotabaya secured 76% of the vote. This sense of disillusionment was evident when thousands from areas like Malabe, Athurugiriya, and Pelawatte—a stronghold of Rajapaksa supporters—joined daily protests for months and ultimately marched 26 kilometers to Colombo on May 9, 2022, to demand his resignation.

This mass movement was not confined to one demographic; it brought together people from all sectors of society, each with their own grievances and aspirations. For the general public, it was primarily about economic hardship and a betrayal of trust. For others, like leftist and progressive groups, it was an opportunity to promote the idea of a revolutionary mass movement aimed at empowering people.

However, the Aragalaya was also marked by significant political and diplomatic interference. Representatives from various political factions—including UNPers sponsored by Ashu Marasinghe, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s allies, Basil Rajapaksa’s agents, Sarath Fonseka’s supporters, and Champika Ranawaka’s supporters were present, each attempting to advance their own agendas. Diplomats from major powers, such as the U.S., India, and China, as well as government intelligence agents, were also actively monitoring and engaging with the movement.

Despite its grassroots energy, the real political shifts occurred in Parliament, not in the streets. The appointment of an interim president was a key moment that divided the movement and eroded its momentum. Opposition parties like the NPP and SJB had the option to reject Ranil Wickremesinghe’s election by refusing to participate in the parliamentary process, aligning with the Aragalaya’s demand for a complete overhaul of the system. Instead, they chose to field their own candidates—Anura Kumara Dissanayake and Dullas Alahapperuma—only to concede and congratulate Wickremesinghe after his victory. These actions were televised, demoralizing many activists who viewed them as a betrayal by the opposition.

An alternative approach, proposed by representatives of the Aragalaya, called for the establishment of an interim government with a six-month mandate, followed by elections. This proposal included forming a cabinet representing all political parties but excluded the concept of an interim president. It was well-received at a meeting at the Public Library Auditorium in Colombo on May 5, 2022, just days before Gotabaya was ousted. However, it failed to gain traction in Parliament, where the ultimate decisions were made.

The Aragalaya, while unprecedented in its scope and inclusivity, was ultimately undermined by political fragmentation, external influences, and the lack of a unified strategy among its leaders and participants. It highlighted the deep disconnection between parliamentary politics and the will of the people, leaving many to question whether meaningful change is possible within the current system.

Features

Trade preferences to support post-Ditwah reconstruction

The manner in which the government succeeded in mobilising support from the international community, immediately after the devastating impact of Cyclone Ditwah, may have surprised many people of this country, particularly because our Opposition politicians were ridiculing our “inexperienced” government, in the recent past, for its inability to deal with the international community effectively. However, by now it is evident that the government, with the assistance of the international community and local nongovernmental actors, like major media organisations, has successfully managed the recovery efforts. So, let me begin by thanking them for what they have done so far.

Yet, some may argue that it is not difficult to mobilise the support for recovery efforts from the international community, immediately after any major disaster, and the real challenge is to sustain that support through the next few weeks, months and years. Because the recovery process, more specifically the post-recovery reconstruction process, requires long-term support. So, the government agencies should start immediately to focus on, in addition to initial disaster relief, a longer-term strategy for reconstruction. This is important because in a few weeks’ time, the focus of the global community may shift elsewhere … to another crisis in another corner of the world. Before that happens, the government should take initiatives to get the support from development partners on appropriate policy measures, including exceptional trade preferences, to help Sri Lanka in the recovery efforts through the medium and the long term.

Use of Trade Preferences to support recovery and reconstruction

In the past, the United States and the European Union used exceptional enhanced trade preferences as part of the assistance packages when countries were devastated by natural disasters, similar to Cyclone Ditwah. For example:

- After the devastating floods in Pakistan, in July 2010, the EU granted temporary, exceptional trade preferences to Pakistan (autonomous trade preferences) to aid economic recovery. This measure was a de facto waiver on the standard EU GSP (Generalised Scheme of Preferences) rules. The preferences, which were proposed in October 2010 and were applied until the end of 2013, effectively suspended import duties on 75 types of goods, including textiles and apparel items. The available studies on this waiver indicate that though a significant export hike occurred within a few months after the waiver became effective it did not significantly depress exports by competing countries. Subsequently, Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014.

- Similarly, after the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal, the United States supported Nepal through an extension of unilateral additional preferences, the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP). This was a 10-year initiative to grant duty-free access for up to 77 specific Nepali products to aid economic recovery after the 2015 earthquakes. This was also a de facto waiver on the standard US GSP rules.

- Earlier, after Hurricanes Mitch and Georges caused massive devastation across the Caribbean Basin nations, in 1998, severely impacting their economies, the United States proposed a long-term strategy for rebuilding the region that focused on trade enhancement. This resulted in the establishment of the US Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA), which was signed into law on 05 October, 2000, as Title II of the Trade and Development Act of 2000. This was a more comprehensive facility than those which were granted to Pakistan and Nepal.

What type of concession should Sri Lanka request from our development partners?

Given these precedents, it is appropriate for Sri Lanka to seek specific trade concessions from the European Union and the United States.

In the European Union, Sri Lanka already benefits from the GSP+ scheme. Under this arrangement Sri Lanka’s exports (theoretically) receive duty-free access into the EU markets. However, in 2023, Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, that is, the ratio of preferential imports to GSP+ eligible imports, stood at 59%. This was significantly below the average utilisation of other GSP beneficiary countries. For example, in 2023, preference utilisation rates for Bangladesh and Pakistan were 90% and 88%, respectively. The main reason for the low utilisation rate of GSP by Sri Lanka is the very strict Rules of Origin requirements for the apparel exports from Sri Lanka. For example, to get GSP benefits, a woven garment from Sri Lanka must be made from fabric that itself had undergone a transformation from yarn to fabric in Sri Lanka or in another qualifying country. However, a similar garment from Bangladesh only requires a single-stage processing (that is, fabric to garment) qualifies for GSP. As a result, less than half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports to the EU were ineligible for the preferences in 2023.

Sri Lanka should request a relaxation of this strict rule of origin to help economic recovery. As such a concession only covers GSP Rules of Origin only it would impact multilateral trade rules and would not require WTO approval. Hence could be granted immediately by the EU.

United States

Sri Lanka should submit a request to the United States for (a) temporary suspension of the recently introduced 20% additional ad valorem duty and (b) for a programme similar to the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP), but designed specifically for Sri Lanka’s needs. As NTPP didn’t require WTO approval, similar concessions also can be granted without difficulty.

Similarly, country-specific requests should be carefully designed and submitted to Japan and other major trading partners.

(The writer is a retired public servant and can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

by Gomi Senadhira

Features

Lasting power and beauty of words

Novelists, poets, short story writers, lyricists, politicians and columnists use words for different purposes. While some of them use words to inform and elevate us, others use them to bolster their ego. If there was no such thing called words, we cannot even imagine what will happen to us. Whether you like it or not everything rests on words. If the Penal Code does not define a crime and prescribe a punishment, judges will not be able to convict criminals. Even the Constitution of our country is a printed document.

A mother’s lullaby contains snatches of sweet and healing words. The effect is immediate. The baby falls asleep within seconds. A lover’s soft and alluring words go right into his or her beloved. An army commander’s words encourage soldiers to go forward without fear. The British wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s words still ring in our ears: “… we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender …”

Writers wax eloquent on love. English novelist John Galsworthy wrote: “Love is no hot-house flower, but a wild plant, born of a wet night, born of an hour of sunshine; sprung from wild seed, blown along the road by a wild wind. A wild plant that, when it blooms by chance within the hedge of our gardens, we call a flower; and when it blooms outside we call a weed; but flower or weed, whose scent and colour are always wild.” While living in a world dominated by technology, we often hear a bunch of words that is colourless and often cut to verbal ribbons – “How R U” or “Luv U.” Such words seem to squeeze the life out of language.

Changing medium

Language is a constantly changing medium. New words and forms arrive and old ones die out. Whoever thought that the following Sinhala words would find a place in the Oxford English Dictionary? “Asweddumize, Avurudu, Baila, Kiribath, Kottu Roti, Mallung, Osari, Papare, Walawwa and Watalappan.” With all such borrowed words the English language is expanding and remains beautiful. The language helps us to express subtle ideas clearly and convincingly.

You are judged by the words you use. If you constantly use meaningless little phrases, you will be considered a worthless person. When you read a well-written piece of writing you will note how words jump and laugh on the paper or screen. Some of them wag their tails while others stand back like shy village belles. However, they serve a useful purpose. Words help us to write essays, poems, short stories and novels. If not for the beauty of the language, nobody will read what you write.

If you look at the words meaningfully, you will see some of them tap dancing while others stand to rigid attention. Big or small, all the words you pen form part of the action or part of the narrative. The words you write make your writing readable and exciting. That is why we read our favourite authors again and again.

Editorials

If a marriage is to succeed, partners should respect and love each other. Similarly, if you love words, they will help you to use them intelligently and forcefully. A recent survey in the United States has revealed that only eight per cent of people read the editorial. This is because most editorials are not readable. However, there are some editorials which compel us to read them. Some readers collect such editorials to be read later.

Only a lover of words would notice how some words run smoothly without making a noise. Other words appear to be dancing on the floor. Some words of certain writers are soothing while others set your blood pounding. There is a young monk who is preaching using simple words very effectively. He has a large following of young people addicted to drugs. After listening to his preaching, most of them have given up using illegal drugs. The message is loud and clear. If there is no demand for drugs, nobody will smuggle them into the country.

Some politicians use words so rounded at the edges and softened by wear that they are no longer interesting. The sounds they make are meaningless and listeners get more and more confused. Their expressions are full of expletives the meaning of which is often soiled with careless use of words.

Weather-making

Some words, whether written or spoken, stick like superglue. You will never forget them. William Vergara in his short essay on weather-making says, “Cloud-seeding has touched off one of the most baffling controversies in meteorological history. It has been blamed for or credited with practically all kinds of weather. Some scientists claim seeding can produce floods and hail. Others insist it creates droughts and dissipates clouds. Still others staunchly maintain it has no effect at all. The battle is far from over, but at last one clear conclusion is beginning to emerge: man can change the weather, and he is getting better at it.”

There are words that nurse the ego and heal the heart. The following short paragraph is a good example. S. Radhakrishnan says, “In every religion today we have small minorities who see beyond the horizon of their particular faith, not through religious fellowship is possible, not through the imposition of any one way on the whole but through an all-inclusive recognition that we are all searchers for the truth, pilgrims on the road, that we all aim at the same ethical and spiritual standard.”

There are some words joined together in common phrases. They are so beautiful that they elevate the human race. In the phrase ‘beyond a shadow of doubt’, ‘a shadow’ connotes a dark area covering light. ‘A doubt’ refers to hesitancy in belief. We use such phrases blithely because they are exquisitely beautiful in their structure. The English language is a repository of such miracles of expression that lead to deeper understanding or emphasis.

Social media

Social media use words powerfully. Sometimes they invent new words. Through the social media you can reach millions of viewers without the intervention of the government. Their opinion can stop wars and destroy tyrants. If you use the right words, you can even eliminate poverty to a great extent.

The choice of using powerful words is yours. However, before opening your mouth, tap the computer, unclip a pen, write a lyric or poem, think twice of the effect of your writing. When you talk with a purpose or write with pleasure, you enrich listeners and readers with your marvellous language skills. If you have a command of the language, you will put across your point of view that counts. Always try to find the right words and change the world for a better place for us to live.

By R. S. Karunaratne

karunaratners@gmail.com

Features

Why Sri Lanka Still Has No Doppler Radar – and Who Should Be Held Accountable

Eighteen Years of Delay:

Cyclone Ditwah has come and gone, leaving a trail of extensive damage to the country’s infrastructure, including buildings, roads, bridges, and 70% of the railway network. Thousands of hectares of farming land have been destroyed. Last but not least, nearly 1,000 people have lost their lives, and more than two million people have been displaced. The visuals uploaded to social media platforms graphically convey the widespread destruction Cyclone Ditwah has caused in our country.

The purpose of my article is to highlight, for the benefit of readers and the general public, how a project to establish a Doppler Weather Radar system, conceived in 2007, remains incomplete after 18 years. Despite multiple governments, shifting national priorities, and repeated natural disasters, the project remains incomplete.

Over the years, the National Audit Office, the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA), and several print and electronic media outlets have highlighted this failure. The last was an excellent five-minute broadcast by Maharaja Television Network on their News First broadcast in October 2024 under a series “What Happened to Sri Lanka”

The Agreement Between the Government of Sri Lanka and the World Meteorological Organisation in 2007.

The first formal attempt to establish a Doppler Radar system dates back to a Trust Fund agreement signed on 24 May 2007 between the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). This agreement intended to modernize Sri Lanka’s meteorological infrastructure and bring the country on par with global early-warning standards.

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations established on March 23, 1950. There are 193 member countries of the WMO, including Sri Lanka. Its primary role is to promote the establishment of a worldwide meteorological observation system and to serve as the authoritative voice on the state and behaviour of the Earth’s atmosphere, its interaction with the oceans, and the resulting climate and water resources.

According to the 2018 Performance Audit Report compiled by the National Audit Office, the GoSL entered into a trust fund agreement with the WMO to install a Doppler Radar System. The report states that USD 2,884,274 was deposited into the WMO bank account in Geneva, from which the Department of Metrology received USD 95,108 and an additional USD 113,046 in deposit interest. There is no mention as to who actually provided the funds. Based on available information, WMO does not fund projects of this magnitude.

The WMO was responsible for procuring the radar equipment, which it awarded on 18th June 2009 to an American company for USD 1,681,017. According to the audit report, a copy of the purchase contract was not available.

Monitoring the agreement’s implementation was assigned to the Ministry of Disaster Management, a signatory to the trust fund agreement. The audit report details the members of the steering committee appointed by designation to oversee the project. It consisted of personnel from the Ministry of Disaster Management, the Departments of Metrology, National Budget, External Resources and the Disaster Management Centre.

The Audit Report highlights failures in the core responsibilities that can be summarized as follows:

· Procurement irregularities—including flawed tender processes and inadequate technical evaluations.

· Poor site selection

—proposed radar sites did not meet elevation or clearance requirements.

· Civil works delays

—towers were incomplete or structurally unsuitable.

· Equipment left unused

—in some cases for years, exposing sensitive components to deterioration.

· Lack of inter-agency coordination

—between the Meteorology Department, Disaster Management Centre, and line ministries.

Some of the mistakes highlighted are incomprehensible. There is a mention that no soil test was carried out before the commencement of the construction of the tower. This led to construction halting after poor soil conditions were identified, requiring a shift of 10 to 15 meters from the original site. This resulted in further delays and cost overruns.

The equipment supplier had identified that construction work undertaken by a local contractor was not of acceptable quality for housing sensitive electronic equipment. No action had been taken to rectify these deficiencies. The audit report states, “It was observed that the delay in constructing the tower and the lack of proper quality were one of the main reasons for the failure of the project”.

In October 2012, when the supplier commenced installation, the work was soon abandoned after the vehicle carrying the heavy crane required to lift the radar equipment crashed down the mountain. The next attempt was made in October 2013, one year later. Although the equipment was installed, the system could not be operationalised because electronic connectivity was not provided (as stated in the audit report).

In 2015, following a UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services) inspection, it was determined that the equipment needed to be returned to the supplier because some sensitive electronic devices had been damaged due to long-term disuse, and a further 1.5 years had elapsed by 2017, when the equipment was finally returned to the supplier. In March 2018, the estimated repair cost was USD 1,095,935, which was deemed excessive, and the project was abandoned.

COPA proceedings

The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) discussed the radar project on August 10, 2023, and several press reports state that the GOSL incurred a loss of Rs. 78 million due to the project’s failure. This, I believe, is the cost of constructing the Tower. It is mentioned that Rs. 402 million had been spent on the radar system, of which Rs. 323 million was drawn from the trust fund established with WMO. It was also highlighted that approximately Rs. 8 million worth of equipment had been stolen and that the Police and the Bribery and Corruption Commission were investigating the matter.

JICA support and project stagnation

Despite the project’s failure with WMO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) entered into an agreement with GOSL on June 30, 2017 to install two Doppler Radar Systems in Puttalam and Pottuvil. JICA has pledged 2.5 billion Japanese yen (LKR 3.4 billion at the time) as a grant. It was envisaged that the project would be completed in 2021.

Once again, the perennial delays that afflict the GOSL and bureaucracy have resulted in the groundbreaking ceremony being held only in December 2024. The delay is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

The seven-year delay between the signing of the agreement and project commencement has led to significant cost increases, forcing JICA to limit the project to installing only one Doppler Radar system in Puttalam.

Impact of the missing radar during Ditwah

As I am not a meteorologist and do not wish to make a judgment on this, I have decided to include the statement issued by JICA after the groundbreaking ceremony on December 24, 2024.

“In partnership with the Department of Meteorology (DoM), JICA is spearheading the establishment of the Doppler Weather Radar Network in the Puttalam district, which can realize accurate weather observation and weather prediction based on the collected data by the radar. This initiative is a significant step in strengthening Sri Lanka’s improving its climate resilience including not only reducing risks of floods, landslides, and drought but also agriculture and fishery“.

Based on online research, a Doppler Weather Radar system is designed to observe weather systems in real time. While the technical details are complex, the system essentially provides localized, uptotheminute information on rainfall patterns, storm movements, and approaching severe weather. Countries worldwide rely on such systems to issue timely alerts for monsoons, tropical depressions, and cyclones. It is reported that India has invested in 30 Doppler radar systems, which have helped minimize the loss of life.

Without radar, Sri Lanka must rely primarily on satellite imagery and foreign meteorological centres, which cannot capture the finescale, rapidly changing weather patterns that often cause localized disasters here.

The general consensus is that, while no single system can prevent natural disasters, an operational Doppler Radar almost certainly would have strengthened Sri Lanka’s preparedness and reduced the extent of damage and loss.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s inability to commission a Doppler Radar system, despite nearly two decades of attempts, represents one of the most significant governance failures in the country’s disastermanagement history.

Audit findings, parliamentary oversight proceedings, and donor records all confirm the same troubling truth: Sri Lanka has spent public money, signed international agreements, received foreign assistance, and still has no operational radar. This raises a critical question: should those responsible for this prolonged failure be held legally accountable?

Now may not be the time to determine the extent to which the current government and bureaucrats failed the people. I believe an independent commission comprising foreign experts in disaster management from India and Japan should be appointed, maybe in six months, to identify failures in managing Cyclone Ditwah.

However, those who governed the country from 2007 to 2024 should be held accountable for their failures, and legal action should be pursued against the politicians and bureaucrats responsible for disaster management for their failure to implement the 2007 project with the WMO successfully.

Sri Lanka cannot afford another 18 years of delay. The time for action, transparency, and responsibility has arrived.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of any organization or institution with which the author is affiliated).

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA national post-cyclone reflection period?