Features

Nadungamuwe Raja, a prisoner of culture, an ambassador of culture or rather, an ambassador of conservation?

By Manasee Weerathunga

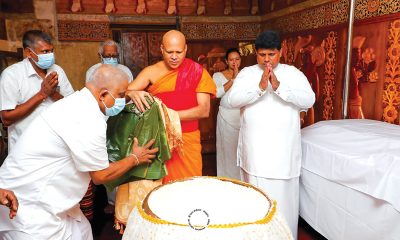

It is no doubt that the passing away of the ceremonial tusker Nadungamuwe Raja was sorrowful news to the entire country, regardless of religions and ethnicities. It is highly unlikely that there could have been any Sri Lankan who did not love this gentle giant for his majesty and tranquility. However, the question at which everyone who loved Nadungamuwe Raja becomes divided, is on whether Nadungamuwe Raja lived a life of grandeur or a life of suffering?

Nadungamuwe Raja is best known as the ceremonial tusker, bearing the main casket of the Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha in the annual procession of Esala, in Kandy, Sri Lanka. As in ancient traditions, it is only a male tusker of remarkable physique that is eligible for bearing the casket of the Tooth Relic. It is this majesty of this beast which prompted many Sri Lankans, especially the devout Buddhists, to place Nadungamuwe Raja, up on a pedestal of sanctitude. In the eyes of devout Buddhists, Nadungamuwe Raja was not only privileged enough to bear the casket of the Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha (something which is not approachable to a layman) but also was able to gather a plethora of merit in this lifetime, for the rest of Samsara, by being in service to the Lord Buddha. However, in the eyes of animal lovers and workers for animal rights, Nadungamuwe Raja was a prisoner of culture and blind religious devoutation, having had lived a life, chained in a domestic setting with no access to the natural habitat of an elephant or its co-inhabitants.

The opulent pair of long, intersecting pair of tusks can be named as the crowning glory of Nadungamuwe Raja, not to mention that he was the tallest domestic elephant known in whole Asia. In addition to these unmistaken resplendent features of Nadungamuwe Raja, the placidity of this beast’s nature, points out some facts noteworthy about elephants. Asian elephants, the species to which Nadungamuwe Raja belongs, differ from their African elephant cousins, with respect to several features. Firstly, Asian elephants are of significantly smaller build in comparison to African elephants, which makes the height of Nadungamuwe Raja, remarkable. Secondly, unlike the African elephant, which possesses tusks in both male and female alike, tusks are a rarity found in some male Asian elephants only, ticking off another box for Nadungamuwe Raja’s exceptionality. Thirdly, domesticated African elephants are unheard of because they do not share the serene demeanor of their Asian counterparts, while Nadungamuwe Raja is only one of the many domestic Asian elephants found in several countries of Asia.

However, domestication of animals is not something which is discrete for a region of the world. The history of animal domestication spans as far as the beginning of human civilization. The pre-historic man of Stone Age was in the habit of chasing and hunting the animals they wanted to fulfill their food requirements, and then moving to a new location once he had exploited all the animals in his surrounding location. However, as the humans moved on to the farming age by growing their food in their locality and forming permanent settlements, they realized that rather than going in search of animals to hunt, holding the animals in captivity, raring them and harvesting the milk, meat and hides that they needed was an easier option. That marked the beginning of animal domestication, resulting in some animal species, such as dogs, cats and ornamental fish breeds, to become fully domesticated species by the present times. A major step in this process involved identifying animals who were passive enough to be approached, caught, and held captive and tamed. This has resulted in the evolution of most domestic animal species to have traits that would make them better suited to a domestic setting while wiping out the traits which would help them survive in the wild. For example, evolution has taken away from the dogs, the traits of aggression shown by their distant relatives, the wolves, as well as any skills of surviving in the wild by hunting and avoiding predation. Therefore, if an enthusiast of animal rights is to argue that holding a gold fish in a fish tank is a violation of its rights and that it would be better off swimming freely in a stream, it is going to be one of the most frivolous points to make because a gold fish would hardly survive in a wild stream for more than 24 hours without getting predated. That is because the ancestors of these domestic animals, running back to hundreds of generations, have not even seen a wild environment so that their genes no longer contain the traits suited for the wild.

However, we cannot say the same about Asian elephants so confidently, because elephants still do exist in the wild and therefore is not a completely domesticated animal species. While the harsher environment that African elephants inhabit has made them more aggressive and violent by their genetic makeup, Asian elephants are more approachable which has enabled many countries to domesticate Asian elephants for centuries. Therefore, a fair number of domestic Asian elephants, found in many countries, are elephants who had been born and bred in domestic settings for generations. Hence, although many activists for animals rights have been voicing out in social media platforms that Nadungamuwe Raja lived a life of suffering by being chained in a domestic setting, having been an elephant born in a domestic elephant stable in India, it is uncertain what percentage of Nadungamuwe’s Raja’s genes still retained the traits that would help him survive in the wild. Usually, several generations of inbreeding of domesticated animals result in establishment of gene combinations best suited for domestic settings and purging those suited for wild environments. Still, it is uncertain how rapidly it happens in each species. With evolutionary biologists and behavioural scientists worldwide conducting a plethora of research on the question of whether nature or nurture determines the behavioural traits of an animal, the question of whether Nadungamuwe Raja would have been happier roaming freely in the wild remains an open question, with not enough data on how much of wild traits that he retained in his genes.

Nevertheless, if we were to assume that Nadungamuwe Raja was still biologically fully capable of living in a wild environment, we should not forget that he would be living in an environment where the humans have become a major predator for elephants. Evolution being a very slow process that takes millions of years, usually the genetic makeup that currently exists in many organisms is the genetic combination that evolved to suit the environmental conditions that existed thousands of years ago. The genome of many organisms is still undergoing the process of adapting to the current environment, which has changed rapidly from what it was a few hundreds of years back. Therefore, organisms do not evolve adaptations to match the changing environmental conditions as rapidly as the environment changes. The same is true for elephants because their genetic makeup has not evolved to keep up with the rapidly changing environment and hence, lack the adaptations to survive the threats posed by their greatest predator of the current world, the human. Therefore, it is fairly agreeable if someone says that Nadungamuwe Raja could have been poached long ago for his magnificent pair of tusks or could have been killed by ‘hakka patas’ traps if it had not lived in the seclusion of a domestic environment. However, it should be noted that Nadungamuwe Raja lived the average lifespan of an Asian elephant. The most common natural cause of death for wild elephants is a mechanical cause resulting from the loss of teeth. Elephants usually have four sets of teeth during their course of life and once the last set of teeth is lost, elephants die a slow and painful death due to the inability to feed and nourish themselves. It is noteworthy that the owners of Nadungamuwe Raja took the utmost effort to preserve the last set of teeth of the elephant so that his lifespan could be prolonged, by meticulously managing the elephant’s diet and behaviour. However, whether living in a natural environment and choosing his own diet from natural sources could have prolonged the lifespan of the elephant is contentious.

The increasing rarity of tusks as sumptuous as Nadungamuwe Raja’s in Asian elephants itself signals an evolutionary trend of elephants towards adaptation to the hostility created in wild environments by humans. It is the general trend of evolution to get rid of any traits that would pose a threat to the survival and fitness of any organism. By evolution, tusks serve the purpose of attracting female mates to male elephants, while helping males with combat with other males for territory and mates as well as obtaining food. With humans as a predator of elephants in wild environments, tusks have unfortunately become the worst nightmare for the survival of elephants in the wild. It is highly probable that the tusks of Nadungamuwe Raja could have brought the same unfortunate fate on him if he had lived in the wild. Even with living a domesticated life, the tusks of Nadungamuwe Raja had been too heavy for his head to bear towards the latter part of his life, although the situation had been ameliorated by his owners by arranging a sleeping place for the elephant where he could rest his head above his body. However, it is doubtful whether the tusks of Nadungamuwe Raja would have grown to that length and weight if it had lived in the wild. If a wild elephant had tusks as long and big as that, it goes without saying that it would pose a hinderance and a danger to the movement of the animal in dense vegetation, which are the common habitats of Asian elephants. Therefore, wild elephants have the habit of wearing off their tusks by rubbing them against tree branches, while the tusks of wild elephants are subjected to breakage during combats between males. For example, Gemunu, who is a well-known tusker inhabiting the Yala National Park of Sri Lanka, had only one tusk until recently, with the other being broken off during a dual. The remaining tusk was also broken off a couple of years earlier, during a dual with Nandimitra, another male elephant of the Yala National Park. Usually, once a male elephant loses his tusks in a combat, it either dies of the wounds of the combat or lives a quiet and short life restricted of mates or food of the territory, without the advantage of tusks. Therefore, another open question remains of whether Nadungamuwe Raja would have had such a luxurious pair of tusks until the end of his lifetime, had he lived in a wild environment.

Considering all these whether Nadungamuwe Raja was a prisoner of culture or not remains a question to be answered based on each person’s own morals and judgment. But, while dividing into sides and splitting hairs to prove whether Nadungamuwe Raja lived a life of a prisoner or that of royalty, there is a fact that many forget. While limiting the discussions about Nadungamuwe Raja to decorating him as an icon of Sri Lankan culture or fighting for his rights for a free life, we forget that not only Nadungamuwe Raja but all other domestic elephants of Sri Lanka which are treated with high esteem can serve a bigger role as ambassadors of environmental conservation. Nadungamuwe Raja and all other celebrated domestic elephants of Sri Lanka such as Kataragama Wasana, Indi Raja, Miyan Raja etc. fit perfectly well to the category of Flagship Species. The concept of Flagship Species introduced by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) includes organisms having an aesthetic importance while representing a certain habitat, issue, or environmental cause. The objective of this concept is by conserving and drawing public attention to these animals which are of aesthetic attraction, the entire habitat they represent will be conserved and the environmental issue that they are involved in would be resolved. The giant panda endemic to China is an ideal example of a flagship species being a successful ambassador in resolving a conservation issue. With the giant panda being categorized as an endangered species by the IUCN in the 1980s, a massive campaign was launched to save China’s beloved national icon. This involved not only in-situ conservation efforts such as setting up nature reserve areas habitable for pandas, but also numerous ex-situ conservation techniques such as breeding pandas in captivity and propagating public interest and awareness on these cute creatures with the use of domesticated pandas held in captivity. These pandas did their job as environmental ambassadors so perfectly that by 2016, IUCN declared that giant pandas are no longer endangered but just vulnerable.

Right now, the number of Sri Lankans who worship Nadungamuwe Raja, holding him at a highly revered position is countless. Similarly, the number of Sri Lankans who fight for animal rights pointing out that Nadungamuwe Raja spent a torturous, miserable life is also fairly high. Amidst all that clamour, the number of elephants killed each year by poachers or by ‘hakka patas’ traps, the number of elephants shot by villagers for encroaching into cultivated lands, the number elephants hit by trains, plus the number of human lives lost each year by wild elephant attacks remain escalating. This disturbing trend signals to us that right now the most serious issue regarding elephants in Sri Lanka is not the debate of whether domestic elephants are cultural icons or prisoners of culture, but the human-elephant conflict which has gone unresolved, yet escalating to an extremely unfortunate level, for the past years. Wild elephants cannot be blamed for the circumstances considering the plight they are in with the construction of motorways fragmenting natural habitats of elephants and blocking their passes, human encroachment into natural habitats limiting the availability of food, water and space for the elephants plus poaching for ivory. On the other hand, the retaliation by humans to wild elephants is also fair considering the threat to property and lives it poses and the economic and emotional turmoil it costs when living in an area of wild elephant threat. That is why Nadungamuwe Raja and his fellow domestic elephants, should be viewed as ambassadors of environmental conservation rather than either icons or prisoners of culture. While thousands of people have been coming to pay their last respects to Nadungamuwe Raja with heavy hearts, while the authorities are taking steps to preserve Nadungamuwe Raja as a national treasure, while Nadungamuwe Raja’s predecessor tusker Raja has a museum dedicated all to himself and preserved and displayed as a national treasure, and while animal rights activists are launching heated social media campaigns to free the domestic elephants from their chains, there are numerous elephants in the island who portray major conservation issues. The wild elephant Natta Kota who roams the premises of tourist hotels bordering the Yala national park, has become a scavenger on garbage of the hotels which lure him to be a tourist attraction. The elephants inhabiting the forests bordering motorways of areas such as Habarana and Buttala had fallen to the plight of mafia gangsters who don’t let vehicles pass unless they are given the ransom of food. The elephants scavenging on garbage dumps of Tissamaharama have fallen to the plight of homeless beggars, picking through trash to fill their stomachs.

It goes without saying that Nadungamuwe Raja is a national treasure because a tusker of that stature and physique is indeed an asset to any country’s natural resource chest. But the reverence shown towards this animal needs to be extended to countless other elephants in Sri Lanka who are at the risk of getting poached for ivory, or killed by traps. As good as it is that Nadungamuwe Raja’s body be preserved as a national treasure as that of Raja, by housing it in a museum as a mere icon of cultural importance, the natural homes of the wild elephants of Sri Lanka needs to be preserved as well, as elephants are assets of Sri Lanka. The activists and enthusiasts of animal rights who voice out protests on the chained life that Nadungamuwe Raja led, should extend their fighting towards winning freedom for the numerous unnamed wild elephants who cannot roam wherever they wish in their native habitats and eat as much natural food as they like. Therefore, it is high time that the authorities start hailing Nandungamuwe Raja as an icon of conservational importance, rather than as a mere national treasure of cultural importance while the worshippers of Nandungamuwe Raja and the fighters for Nandungamuwe Raja’s animal rights start portraying him as an ambassador of environmental conservation rather than an ambassador of culture or a prisoner of culture.

(The writer is a PhD Student in Evolutionary Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, US. She thanks Gihan Athapaththu, former Naturalist at Jetwing Yala, currently Master’s student at Jeju National University, South Korea, for his contribution to this article.)

Features

Pharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

Yet again, deaths caused by questionable quality pharmaceuticals are in the news. As someone who had worked in this industry for decades, it is painful to see the way Sri Lankans must face this tragedy repeatedly when standard methods for avoiding them are readily available. An article appeared in this paper (Island 2025/12/31) explaining in detail the technicalities involved in safeguarding the nation’s pharmaceutical supply. However, having dealt with both Western and non-Western players of pharmaceutical supply chains, I see a challenge that is beyond the technicalities: the human aspect.

There are global and regional bodies that approve pharmaceutical drugs for human use. The Food and Drug Administration (USA), European Medicines Agency (Europe), Medicine and Health Products Regulatory Agency (United Kingdom), and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan) are the major ones. In addition, most countries have their own regulatory bodies, and the functions of all such bodies are harmonized by the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) and World Health Organization (WHO). We Sri Lankan can take solace in knowing that FDA, the premier drug approval body, came into being in 1906 because of tragedies similar to our own. Following the Elixir Sulfanilamide tragedy that resulted in over one hundred deaths in 1938 and the well-known Phthalidomide disaster in 1962, the role and authority of FDA has increased to ensure the safety and efficacy of the US drug supply.

Getting approval for a new proprietary pharmaceutical is an expensive and time-consuming affair: it can take many billions of dollars and ten to fifteen years to discover the drug and complete all the necessary testing to prove safety and efficacy (Island 2025/01/6). The proprietary drugs are protected by patents up to twenty years, after which anyone with the technical knowhow and capabilities can manufacture the drug, call generics, and seek approval for marketing in countries of their choice. This is when the troubles begin.

Not having to spend billions on discovery and testing, generics manufactures can provide drugs at considerable cost savings. Not only low-income countries, but even industrial countries use generics for obvious reasons, but they have rigorous quality control measures to ensure efficacy and safety. On the other hand, low-income countries and countries with corrupt regulatory systems that do not have reasonable quality control methods in place become victims of generic drug manufacturers marketing substandard drugs. According to a report, 13% of the drugs sold in low-income countries are substandard and they incur $200 billion in economic losses every year (jamanetworkopen.2018). Sri Lankans have more reasons to be worried as we have a history of colluding with scrupulous drug manufactures and looting public funds with impunity; recall the immunoglobulin saga two years ago.

The manufacturing process, storage and handling, and the required testing are established at the time of approval; and they cannot be changed without the regulatory agency’s approval. Now a days, most of the methods are automated. The instruments are maintained, operated, and reagents are handled according to standard operating procedures. The analysts are trained and all operations are conducted in well maintained laboratories under current Good Manufacturing Procedures (cGMP). If something goes wrong, there is a standard procedure to manage it. There is no need for guess work; everything is done following standard protocols. There is traceability; if something went wrong, it is possible to identify where, when, and why it happened.

Setting up a modern analytical laboratory is expensive, but it may not cost as much as a new harbor, airport, or even a few kilometers of new highway. It is safe to assume that some private sector organizations may already have a couple of them running. Affordability may not be a problem. But it is sad to say that in our part of the world, there is a culture of bungling up the best designed system. This is a major concern that Western pharmaceutical companies and regulatory agencies have in incorporating supply chains or services from our part of the world.

There are two factors that foster this lack of work ethics: corruption and lack of accountability. Admirably, the private sector has overcome this hurdle for the most part, but in the public sector, from top to bottom, lack of accountability and corruption have become a pestering cancer debilitating the economy and progress. Enough has been said about corruption, and fortunately, the present government is making an effort to curb it. We must give them some time as only the government has changed, not the people.

On the other hand, lack of accountability is a totally alien concept for our society. In many countries, politicians are held accountable at elections. We give them short breaks, to be re-elected at the next election, often with super majorities, no matter how disastrous their actions were. When it comes to government servants, we have absolutely no way to hold them accountable. There is absolutely no mechanism in place; it appears that we never thought about it.

Lack of accountability refers to the failure to hold individuals responsible for their actions. This absence of accountability fosters a culture of impunity, where corrupt practices can thrive without fear of repercussions. In Sri Lanka, a government job means a lifetime employment. There is no performance evaluation system; promotions and pay increases are built in and automatically implemented irrespective of the employee’s performance or productivity. The worst one can expect for lapses in performance is a transfer, where one can continue as usual. There is no remediation. To make things worse, often the hiring is done for political reasons rather than on merit. Such employees have free rein and have no regard for job responsibilities. Their managers or supervisors cannot take actions as they have their political masters to protect them.

The consequences of lack of accountability in any area at any level are profound. There is no need to go into detail; it is not hard to see that all our ills are the results of the culture of lack of accountability, and the resulting poor work ethics. Not only in the pharmaceuticals arena, but this also impacts all aspects of products and services available. If anyone has any doubts, they should listen to COPE committee meetings. Without a mechanism to hold politicians, government employees, and bureaucrats accountable for their actions or lack of it, Sri Lanka will continue to be a developing country forever, as has happened over the last seventy years. As a society, we must take collective actions to demand transparency, hold all those in public service accountable, and ensure that nation’s resources are used for the benefit of all citizens. The role of ethical and responsible journalism in this respect should not be underestimated.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D. ✍️

Features

Tips for great sleep

Although children can sleep well, most adults have trouble getting a good night’s sleep. They go to bed each night, but find it difficult to sleep. While in bed they toss and turn until daybreak. Such people cannot be expected to do any work properly. Upon waking they get ready to go for work, but they feel exhausted. While travelling to workplaces they doze off on buses and trains. In fact sleep deprivation leads to depression. Then they seek medical help to get over the problem.

Some people take sleeping pills without consulting a doctor. Sleeping pills might work for a few days, but you will find it difficult to drag yourself out of bed. What is more, you will feel drowsy right throughout the day. If you take sleeping pills regularly, you will get addicted to them.

A recent survey has revealed that millions of Asians suffer from insomnia – defined as an inability to fall asleep or to sleep through the night. When you do not get enough sleep for a long time, you might need medical treatment. According to a survey by National University Hospital in Singapore, 15 percent of people in the country suffer from insomnia. This is bad news coming from a highly developed country in Asia. It is estimated that one third of Asians have trouble sleeping. As such it has become a serious problem even for Sri Lankans.

Insomnia

Those who fail to take proper treatment for insomnia run the risk of sleep deprivation. A Japanese study reveals that those who sleep five hours or less are likely to suffer a heart attack. A healthy adult needs at least seven hours of sleep every day. When you do not get the required number of hours for sleep, your arteries may be inflamed. Sleep deprived people run the risk of contracting diabetes and weight gain. An American survey reveals that children who do not get deep sleep may be unnaturally small. This is because insomnia suppresses growth hormones.

It is not the length of sleep that matters. The phases of sleep are more important than the number of hours you sleep. Scientists have found that we go through several cycles of 90 minutes per night. Every cycle consists of three phases: light sleep, slumber sleep and dream sleep. When you are in deep sleep your body recuperates. When you dream your mind relaxes. Light sleep is a kind of transition between the two.

Although adults should get a minimum seven hours of sleep, the numbers may vary from person to person. In other words, some people need more than seven hours of sleep while others may need less. After the first phase of light sleep you enter the deep sleep phase which may last a few minutes. The time you spend in deep sleep may decrease according to the proportion of light sleep and dream sleep.

Napoleon Bonaparte

It is strange but true that some people manage with little sleep. They skip the light sleep and recuperate in deep sleep and dream sleep. For instance, Napoleon Bonaparte used to sleep only for four hours a night. On the other hand, we sleep at different times of the day. Some people – known as ‘Larks’ – go to bed as early as 8 p.m. There are ‘night owls’ who go to bed after midnight. Those who go to bed late and get up early are a common sight. Some of them nod off in the afternoon. This shows that we have different sleep rhythms. Dr Edgardo Juan L. Tolentino of the Philippine Department of Health says, “Sleep is as individual as our thumb prints and patterns can vary over time. Go to bed only when you are tired and not because it’s time to go to bed.”

If you are suffering from sleep deprivation, do not take any medication without consulting a doctor. Although sleeping pills can offer temporary relief, you might end up as an addict. Therefore take sleeping pills only on a doctor’s prescription. He will decide the dosage and the duration of the treatment. What is more, do not increase the dose yourself and also do not take them with alcohol.

You need to exercise your body in order to keep it in good form. However, avoid strenuous exercises late in the evening because they would stimulate the body and increase the blood circulation. This does not apply to sexual activity which will pave the way for sound sleep. If you are unable to enjoy sleep, have a good look at your bedroom. The bedroom and the bed should be comfortable. You will also fall asleep easily in a quiet bedroom. Avoid bright lights in the bedroom. Use curtains or blinds to darken the bedroom. Use a quality mattress with proper back support.

Methods

Before consulting a doctor, you may try out some of the methods given below:

* Always try to eat nutritious food. Some doctors advise patients to take a glass of red wine before going to bed. However, too much alcohol will ruin your sleep. Avoid smoking before going to bed because nicotine impairs the quality of sleep.

* Give up the habit of drinking a cup of coffee before bedtime because caffeine will keep you awake. You should also avoid eating a heavy meal before going to bed. A big meal will activate the digestive system and it will not allow the body to wind down.

* Always go to bed with a relaxed mind. This is because stress hormones in the body can hinder sleep. Those who lead stressful lives often have trouble sleeping. Such people should create an oasis between the waking day’s events and going to bed. The best remedy is to go to bed with a novel. Half way through the story you will fall asleep.

* Make it a point to go to bed at a particular time every day. When you do so, your body will get attuned to it. Similarly, try to get up at the same time every day, including holidays. If you do so, such practices will ensure your biological rhythm.

* Avoid taking a long nap in the afternoon. However, a power nap lasting 20 to 30 minutes will revitalise your body for the rest of the day.

* If everything fails, seek medical help to get over your problem.

(karunaratners@gmail.com)

By R.S. Karunatne

Features

Environmental awareness and environmental literacy

Two absolutes in harmonising with nature as awareness sparks interest – Literacy drives change

Hazards teach lessons to humanity.

Before commencing any movement to eliminate or mitigate the impact of any hazard there are two absolutes, we need to pay attention to. The first requirement is for the society to gain awareness of the factors that cause the particular hazard, the frequency of its occurrence, and the consequences that would follow if timely action is not taken. Out of the three major categories of hazards that have been identified as affecting the country, namely, (i) climatic hazards (floods, landslides, droughts), (ii) geophysical hazards (earthquakes, tsunamis), and (iii) endemic hazards (dengue, malaria), the most critical category that frequently affect almost all sectors is climatic hazards. The first two categories are natural hazards that occur independently of human intervention. In most instances their occurrence and behaviour are indeterminable. Endemic hazards are a combination of both climatic hazards and human negligence.

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS

‘In Ceylon it never rains but pours’ – Cyclone Ditwah and Our Experiences

Climatic hazards, as experienced in Sri Lanka are dependent on nature, timing and volume of rainfall received during a year. The patterns of rainfall received indicate that, in most instances, rainfalls follow a rhythmic pattern, and therefore, their advent and ferocity as well as duration could in most instances be forecast with near accuracy. Based on analyses of long-term mean monthly rainfall data, Dr. George Thambyahpillay (Citation, University of Ceylon Review vol. XVI No. 3 & 4 Jul.-Oct 1958, pp 93-106 1958) produced a research paper wherein he exposed a certain Rainfall Rhythm in Ceylon. He opens his paper with the statement ‘In Ceylon it never rains but it pours’, which clearly shows both the velocity and the quantum of rain that falls in the island. ‘It is an idiom which expresses that ‘when one bad thing happens, a lot of other bad things also happen, making the situation even worse’. How true it is, when we reminisce short and long term impacts of the recent Ditwah cyclone.

Proving the truism of the above phrase we have experienced that many climatic hazards have been associated with the two major seasonal rainy phases, namely, the Southwest and Northeast monsoons, that befall in the two rainy seasons, May to September and December to February respectively. This pattern coincides with the classification of rainy seasons as per the Sri Lanka Met Department; 1) First inter-monsoon season – March-April, 2) Southwest monsoon – May- September, 3) Second Inter-monsoon season – October-November, and 4) Northeast monsoon – December-February.

The table appearing below will clearly show the frequency with which climatic hazards have affected the country. (See Table 1: Notable cyclones that have impacted Sri Lanka from 1964-2025 (60 years)

A marked change in the rainfall rhythm experienced in the last 30 years

An analysis of the table of cyclones since 1978 exposes the following important trends:

(i) The frequency of occurrence of cyclones has increased since 1998,

(ii) Many cyclones have affected the northern and eastern parts of the country.

(iii) Ditwah cyclone diverged from this pattern as its trajectory traversed inland, affecting the entire island. (similar to cyclones Roanu and Nada of 2016).

(iv) A larger number of cyclones occur during the second inter-monsoon season during which Inter-Monsoonal Revolving Storms frequently occur, mainly in the northeastern seas, bordering the Bay of Bengal. Data suggests the Bay of Bengal has a higher number of deadlier cyclones than the Arabian Sea.

(v) Even Ditwah had been a severe cyclonic outcome that had its origin in the Bay of Bengal.

(vi) There were several cyclones in the years 2016 (Roanu and Nada), 2020 (Nivar and Burevi), 2022 (Asani and Mandous) and 2025 (Montha and Ditwah). In 2025, exactly a month before Ditwah, (November 27, 2025) cyclone Montha affected the country’s eastern and northern parts (October 27) – a double whammy.

(vii) Climatologists interpret that Sri Lanka being an island in the Indian Ocean, the country is vulnerable to cyclones due to its position near the confluence of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

(viii) The island registers increased cyclonic activity, especially in the period between October and December.

The need to re-determine the paddy cultivation seasons Yala and Maha vis-a-vis changing rainfall patterns

Sri Lanka had been faithfully following the rainfall patterns year in year out, in determining the Maha and Yala paddy cultivation seasons. The Maha season falls during the North-east monsoon from September to March in the following year. The Yala season is effective during the period from May to August. However, the current changes in the country’s rainfall pattern, would demand seriously reconsidering these seasons numerous cyclones had landed in the past few years, causing much damage to paddy as well as other cultivations. Cyclones Montha and Ditwah followed one after the other.

The need to be aware of the land we live in Our minds constantly give us a punch-list of things to fixate on. But we wouldn’t have ever thought about whether the environments we live in or do our businesses are hazardous, and therefore, that item should be etched in our punch-list. Ditwah has brought us immense sorrow and hardships. This unexpected onslaught has, therefore, driven home the truth that we need to be ever vigilant on the nature of the physical location we live in and carry on our activities. Japanese need not be told as to how they should act or react in an earthquake or a tsunami. Apart from cellphone-indications almost simultaneously their minds would revolve around magnitude of the earthquake and seismic intensity, tsunami, fires, electricity and power, public transportation, and what to do if you are inside a building or if you are outdoors.

Against this backdrop it is really shocking to know of the experiences of both regional administrators and officials of the NBRO (National Building Research Organisation) in their attempts to persuade people to shift to safer locations, when deluges of cyclone Ditwah were expected to cause floods and earth slips/ landslides

Our most common and frequently occurring natural hazards

Apart from the Tsunami (December 26, 2004), that caused havoc in the Northeastern and Southern coastal belts in the country, our two most natural hazards that take a heavy toll on people’s lives and wellbeing, and cause immense damage to buildings, plantations, and critical infrastructure have been periodic floods and landslides. It has been reported that Ditwah has caused ‘an estimated $ 4.1 billion in direct physical damage to buildings, agriculture and critical infrastructure, which include roads, bridges, railway lines and communication links. It is further reported that total damage is equivalent to 4% of the country’s GDP.’

Floods and rain-induced landslides demand high alert and awareness

As the island is not placed within the ‘Ring of Fire’ where high seismic activity including earthquakes and volcanic activity is frequent, Sri Lanka’s notable hazards that occur almost perennially are floods and landslides; these calamities being consequent upon heavy rains falling during both the monsoonal periods, as well as the intermonsoonal periods where tropical revolving storms occur. When taking note of the new-normal rhythm of the country’s rainfall, those living in the already identified flood-basins would need to be ever vigilant, and conscious of emergency evacuation arrangements. Considering the numbers affected and distress caused by floods and disruptions to commercial activities, in the Western province, some have opined that priority would have been given to flood-prevention schemes in the Kelani river basin, over the Mahaweli multi-development programme.

Geomorphic processes carry on regardless, in reshaping the country’s geomorphological landscape

Geomorphic processes are natural mechanisms that eternally shape the earth’s surface. Although endogenic processes originating in the earth’s interior are beyond human control, exogenic processes occur continuously on or near the earth’s surface. These processes are driven by external forces, which mainly include:

(i) Weathering: rock-disintegration through physical, chemical and biological processes, resulting in soil and sediment formation.

(ii) Erosion: Dislocation/ removal and movement of weathered materials by water and wind (as ice doesn’t play a significant role in the Tropics).

(iii) Transportation: The shifting of weathered material to different locations often by rivers, wind, heavy rains,

(iv) Deposition: Transported material being settled forming new landforms, lowering of hills, and flattening of undulated land or depositing in the seabed.

What we witnessed during heavy rains caused by cyclone Ditwah is the above process, what geomorphologists refer to as ‘denudation’. This process is liable to accelerate during spells of heavy rain, causing landslides, landfalls, earth and rock slips/ rockslides and landslides along fault lines.

Hence, denudation is quite a natural phenomenon, the only deviation being that it gets quickened during heavy rains when gravitational and other stresses within a slope exceed the shear strength of the material that forms slopes.

It is, therefore, a must that both people and relevant authorities should be conscious of the consequences, as Ditwah was not the first cyclone that hit the country. Cyclone Roanu in May 2016 caused havoc by way of landslides, Aranayake being an area severely affected.

Conscious data-studies and analyses and preparedness; Two initials to minimise potential dangers

Sri Lanka has been repeatedly experiencing heavy rain–related disasters as the table of cyclones clearly shows (numbering 22 cyclones within the last 60 years). Further, Sri Lanka possesses comprehensive hazard profiles developed to identify and mitigate risks associated with these natural hazards.

A report of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, says “Rain induced landslides occur in 13 major districts in the central highland and south western parts of the country which occupies about 20-30% of the total land area, and affects 30-38% of total population (6-7.6 Million). The increase of the number of landslides and the affected areas over the years could be attributed to adverse changes in the land use pattern, non-engineered constructions, neglect of maintenance and changes in the climate pattern causing high intensity rainfalls.”

ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY

Environmental awareness being simply knowing facts will be of no use unless such knowledge is coupled with environmental literacy. Promoting environmental literacy is crucial for meeting environmental challenges and fostering sustainable development. In this context literacy involves understanding ecological principles and environmental issues, as well as the skills and techniques needed to make informed decisions for a sustainable future. This aspect is the most essential component in any result-oriented system to mitigate periodic climate-related hazards.

Environmental literacy rests upon several crucial pillars

The more important pillars among others being:

· Data-based comprehensive knowledge of problems and potential solutions

· Skills to analyse relevant data and information critically, and communicate effectively the revelations to relevant agencies promptly and accurately.

· Identification and Proper interconnectedness among relevant agencies

· Disposition – The attitudes, values and motivation that drive responsible environmental behaviour and engagement.

· Action – The required legal framework and the capacity to effectively translate knowledge, skills and disposition into solid action that benefits the environment.

· Constant sharing of knowledge with relevant international bodies on the latest methods adopted to harmonise human and physical environments.

· Education programmes – integrating environmental education into formal curricula and equipping students with a comprehensive understanding of ecosystems and resource management. Re-structuring the geography syllabus, giving adequate emphasis to environmental issues and changing patterns of weather and overall climate, would seem a priority act.

· Experiential learning – Organising and engaging in field studies and community projects to gain practical insights into environmental conservation.

· Establishing area-wise warning systems, similar to Tsunami warning systems.

· Interdisciplinary Approaches to encourage students to relate ecological knowledge with such disciplines as geology, geography, economics and sociology.

· Establishing Global Collaboration – Leveraging technology and digital platforms to expand access to environmental education and enhance awareness on global environmental issues.

· Educating the farming community especially on the changes occurring in weather and climate.

· Circumventing high and short duration rainfall extremes by modifying cultivation patterns, and introducing high yielding short-duration yielding varieties, including paddy.

· Soil management that reduces soil erosion

· Eradicating misconceptions that environmental literacy is only for scientists (geologists), environmental professionals and relevant state agencies.

A few noteworthy facts about the ongoing climatic changes

1. The year 2025 was marked by one of the hottest years on record, with global

temperatures surpassing 1.5ºC.

2. Russia has been warming at more than twice the global average since 1976, with 2024 marking the hottest year ever recorded.

3. Snowfalls in the Sahara – a rare phenomenon, with notable occurrences recorded in recent years.

4. Monsoon rains in the Indian Subcontinent causing significant flooding and landslides

5. Warming of the Bay of Bengal, intensifying weather activity.

6. The Himalayan region, which includes India, Nepal, Pakistan, and parts of China, experiencing temperatures climbing up to 2ºC above normal, along with widespread above-average rainfall.

7. Sri Lanka experienced rainfall exceeding 300 m.m. in a single day, an unprecedented occurrence in the island’s history. Gammaduwa, in Matale, received 540 m.m. of rainfall on a day, when Ditwah rainfall was at its peak.

The writer could be contacted at kalyanaratnekai@gmail.com

by K. A. I. KALYANARATNE ✍️

Former Management Consultant /

Senior Manager, Publications

Postgraduate Institute of Management,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Vice President, Hela Hawula

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance