Opinion

Misbehaving monks, and laypersons’ responsibility

I refer to the opinion piece titled ‘Tears of hypocrisy’ – a response by G.A. D. Sirimal in The Island of 01 March.

Referring to one of your previous editorials where you have raised the question as to why the Mahanayaka Theras wouldn’t care to rein in unruly monks, Sirimal wanted to know what happened to a resolution tabled at the 86th Annual General meeting of the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress in Kandy proposing the formation of a Sangharaja Mandalaya to hear complaints against the members of the Sangha. This forum was to be vested with powers to impose penalties on those found guilty and, if required, to expel the culprits from the order.

While this idea seems a well-meaning one at least at the surface, before trying out any solutions, one needs to dig deeper into the root of this multi-faceted problem to get a clear understanding of where the things have really gone wrong.

First thing to do is to reflect on the fundamental questions of “who a Buddhist monk really is or what sets a Buddhist monk apart from the rest of us?”. From what we could surmise from the Buddha’s original teachings, a Bhikku is someone who voluntarily leaves the worldly affairs to find a path of peace, essentially by cultivating a deeper understanding of how the human mind works. Such a person would deserve the respect and support from others, but if and only if they stick to that challenging path. This should essentially be the only basis of the respectful and supportive relationship the laymen might have with a Buddhist monk. In other words, it’s simply a social contract – not a legal contract – where respect or support needs to be earned by monks, just like in any other social relationship.

The sure and most effective solution to the issue of unruly or “un-Buddhist” monks lies not with any Sangharaja Mandalaya but with the laypeople themselves. It’s a matter of simply going back to the underlying social contract, the breach of which should mean ending the laypeople’s side of the bargain. It’s as simple as that. Why do we care to feed, house and respect anyone who is more concerned about sorting out worldly affairs than about their pursuance of the path of peace advocated by the Buddha?

Once the social contract between the laypeople and a monk ends, it should no longer be an issue or a worry for the laypeople as to what that monk is up to. Just as any other individual in the society, that monk should also be free to live in any manner of their choosing as long as the country’s laws are not compromised. For instance, someone wearing a yellow robe and drinking alcohol shouldn’t bother any layperson in the absence of any current social contract with that wearer. It shouldn’t be treated as a criminal offence either. However, driving while being drunk should be a criminal offence irrespective of what one was wearing at the time and should be dealt with strictly according to the law.

A wearer of any dress of any colour or form should also be free to earn money, participate in politics, engage in protests, jump over the walls, etc., as long as no law is broken. It’s up to the laypeople not to afford the respect and support they may otherwise deserve or demand. Our society is steeped in this tradition of respecting and supporting anyone who wears a yellow robe. This is partly the result of the society’s deep dependence on the ritualistic aspects that have crept into the popular Buddhist practice.

If we are to solve this problem of unruly and misbehaving monks, ending our social contract with them pronto is the easiest and surest way to achieve it. Once the laypeople have done their bit, the rest can be left for either the Mahanayakas or any Sangharaja Mandalaya to deal with as they think fit.

Upul P, Auckland.

Opinion

Columbia protesters taken into custody after police enter campus—CBS News

by Thalif Deen

At a press conference last Tuesday night, New York City Mayor and his Police Commissioner tried to justify police intervention against pro-Palestinian demonstrators at Columbia University claiming the protests have been corrupted by “outside agitators.”

I think this is a steaming pile of horse shit (forget bulls).

Last Saturday, I visited the site. The entire campus was on a locked-down mode. Of the seven or eight entrances and exits, only one was open, with several security officers standing by. Only current students, academics —and the press– were allowed in. The security checks were tight.

How “outside agitators” infiltrated the campus beats me—unless they parachuted or were air-dropped on the sprawling campus.? Like American food drops in Gaza.

I noticed the only press pass valid was the New York city press pass issued in collaboration with the New York Police Department (NYPD) — although I was also armed with the UN press pass, the US State Department press ID and my Columbia student ID of a bygone era.

The 80 tents brought back memories because they occupied the huge lawn opposite the Journalism School. I still remember a creative sign on that lawn back in my student days: “IF ALLOWED TO GROW, THIS GRASS WILL PRODUCE ENOUGH OXYGEN FOR TWO STUDENTS TO BREATHE FOR ONE SEMESTER”.

Forget “KEEP OFF THE GRASS”.

(The writer, a former journalist on the old Ceylon Observer, was a Fulbright student at the Columbia School of Journalism in the seventies. He worked in Hong Kong for about a year before returning to the U.S. where he lives and has long headed the UN Bureau of the Inter Press Service (IPS).)

Opinion

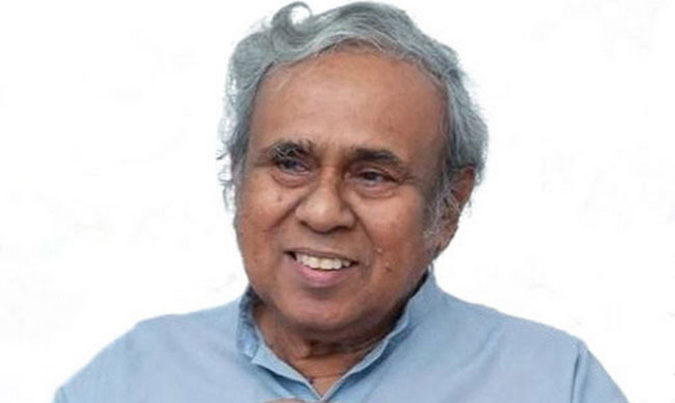

Nalin de Silva, his world and our worlds

It is hard to think of any Sri Lankan academic who has been vilified the way Nalin Kumar De Silva was. Nalin was not averse to calling out his ideological opponents and not in very polite terms either, but all those epithets essentially boiled down to ‘Pawns of the West,’ nothing more. He was, on the other hand, called racist, chauvinist and warmonger. Some, who obviously were clueless about ‘nation’ would call him ‘nationalist’ as though that was some kind of four-letter word.

There were others who referred to Nalin and his ideological comrade Gunadasa Amarasekera as ‘native intellectuals.’ They probably didn’t understand the word ‘intellect’ and its derivatives. I believe it was Nalin or maybe it was Gunadasa who observed that the term implied ‘international intellectuals.’ Perhaps those who called them ‘native intellectuals’ did so to confer upon themselves the tag ‘international intellectual’ but the very use of the term disqualified them, obviously. Pawns they were and are, Nalin believed.

The more informed, less threatened and less malicious referred to him as one of the two top ideologues of what was known as the ‘Jathika Chinthanaya School’ (the other being Gunadasa). No one has really succeeded in translating ‘Jathika Chinthanaya’ into English. ‘National Ideology’ somehow seems crude and erroneous. Those who subscribed to this school of thought, however, knew. They had a sense.

Nalin passed away in California, USA just a few hours before I started writing this. The final rites will be held from 1 to 5 pm (PST) on Sunday, May 5 at Fremont Blvd, Fremont. It is probably too soon to offer a comprehensive review of his work, as a teacher, political activist and thinker. It has to be mostly anecdotal but maybe that’s all I can do, not having associated with him closely.

Like most people who ‘knew’ Nalin, knowledge came mostly from reading what he has written. ‘Magey Lokaya’ (My world), probably the essay that best captures his theoretical explorations, is probably one of the most influential political treatises of the late 20th century. There were other books which addressed what was dubbed ‘The ethnic conflict’ where Nalin cogently tore apart the creative historiography of Eelamists and their apologists who had many axes to grind with the Sinhalese and/or Buddhists. In addition there were innumerable articles published weekly in the Divaina, Vidusara and later in the Midweek Review of ‘The Island.’ I’ll come to those later.

The first time I met him was when I went to see my friend and teacher Arjuna Parakrama. This was in the early 1990s. We were walking towards the ‘Open Canteen’ of the Colombo University when we ran into Nalin. Apparently the two had agreed to a debate. Arjuna said something about the logistics and added, ‘we must make sure we don’t become pawns of other people.’ Nalin muttered something with a laugh and walked away. Arjuna had heard: ‘he said I am a pawn.’ Arjuna didn’t take it as an insult. I don’t know if the debate did take place, but Arjuna told me years later that Nalin had acknowledged that he, Arjuna, was a good trade unionist. This was when Nalin had been suspended by the university.

My first one-on-one encounter happened in the late nineties. I was a student in the USA at the time and had written to Nalin. I was politically associated with the ‘Janatha Mithuro’ then and felt that Nalin’s ongoing clashes with Champika Ranawaka were unnecessary. I mentioned this. Nalin replied. He was ‘soft’ in the criticism. He merely stated, ‘No one disputes that Champika is very bright, but he should acknowledge the source of his ideas.

’ Champika, after he disassociated himself from the JVP-led student movement, was one of the prominent acolytes of Nalin’s ‘Chinthana Parshadaya.’ Convinced that a political movement and not a forum to discuss ideological/philosophical matters was what was needed, he, along with other young people who had become skeptical about Marxism, launched first the Ratawesi Peramuna and later the Janatha Mithuro. Nalin was one of their strongest critics.

I met him next at the Divaina editorial office. It must have been in 2001. I was working at the Sunday Island but enjoyed spending an hour or two at the Divaina. One day I saw Nalin and after saying hello, asked him if he had come to hand over an article. What follows is the rough English translation of what he told me in Sinhala. ‘No Malinda. You know, it’s a small amount that they pay me, but it is not small for me; even so it is irregular.’ It was the only income he had at the time.

In 2006 in Celigny, Switzerland, at a media opportunity just prior to the commencement of talks between the Government and the LTTE, I casually asked Jehan Perera of the National Peace Council who happened to be there, ‘how many people could you get to Lipton Circus for a protest if you didn’t have funding?’ Jehan, ideologically at odds with me though he was, offered an honest response: ‘probably none.’

That was the difference. The NGOs had bucks. They had, in 2002, a government committed to federalism and a president who was not in disagreement. They had both the private and state media at their disposal. The nationalists had Nalin and a few others.

The 1990s were all about federalism. Those opposed to federalism were called warmongers, racists and chauvinists. Nalin got a lot of that. And yet, after it had led to the ridiculous Ceasefire Agreement signed on February 22, 2002 and the consequent pantomime of ‘peace’ talks, federalism became a joke. The UPFA routed the UNP in April 2004 and Mahinda Rajapaksa pipped Ranil Wickremesinghe at the presidential election the following year, admittedly with some help from the LTTE which called for a boycott, probably costing Ranil the election.

That turn around in the fortunes of the nationalists may have surprised the Anglicized sections of the population, but what they probably never understood is the role played by Nalin, Gunadasa and others for well over two decades countering every lie of the Eelsmists, their apologists and other colonial remnants who can’t get enough of the English and English.

Several years later, in a new political avatar where he spoke of the bodisatva ‘Natha Deyyo,’ inviting much ridicule and invective, paradoxically from those who fervently believe in a creator god, immaculate conception, rising from the dead and so on, Nalin wrote ‘Batahira vidyava saha deviyo (Western science and god).’ I was invited to speak at the launch, as was Prof Carlo Fonseka.

Carlo, as irrepressible as Nalin, opted to focus on a chapter that the author had suggested he avoid. Nalin, responding, completely refuted Carlo. He had said, in Sinhala, ‘I didn’t want to do that to him; I knew I would have to if he chose to focus on that chapter; he did and I had no choice but to take him apart.’

In retrospect one could argue that Nalin should have avoided supporting politicians and political parties, but those moments hardly make a dent in the enormous contributions he has made to the political and ideological discourse in and on post Independence Sri Lanka. At worst, his texts need to be engaged with. Indeed, his detractors cannot but have a conversation with his works.

Nalin, for all his lectures on the chathuskotikaya (in opposition to the dvikotiyaka or the dialectic) was eminently dialectic in his political engagements, possibly a habit acquired during his Trotskyite days which he failed to shed after he felt Marxism was an inadequate and even erroneous doctrine. This is probably why he was often ‘in your fact’ with political and ideological opponents and found it hard to work with and develop a group of like-minded thinkers/activists. Again, this is hardly a serious crime. To me, anyway, he was an exceptional thinker and an influencer unlike any other over the past 40 years.

Nalin was indefatigable. He was all over the newspapers and when social media became fashionable he adapted quickly, writing daily posts using language appropriate to this new media culture. His last post was just a few days ago; in fact he mentioned that he was unwell and will not be writing for a few days. He won’t write again but he’s written so much that it would take years for anyone to go through the full corpus of his writings. He was, in his writing and his engagements, relentless.

May his sojourn through Sansara be brief.

Malinda Seneviratne

Opinion

A fine example of non-alignment

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was an important feature in international relations during the period of the Cold War between West and East. The Cold War is now over and the world is a more complex place in which many power blocs and alliances can be observed.

While the NAM is no longer relevant, the principle of non-alignment remains relevant specially for small countries like Sri Lanka. Our country can remain faithful to the principle of non-alignment and the commitment to the United Nations.

In the last two years, Sri Lanka has pursued that kind of policy. Sending a warship to engage with the Houthis while inviting the President of Iran to Sri Lanka is a fine example of the principle of non-alignment in practice.

Leelananda de Silva

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoINSEE Ecocycle marks 21 years of environmental excellence with a city cleaning program in Anuradhapura

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoCalling applications for MBBS!

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoUS visa issues deny Sri Lanka Olympic qualifying opportunity in Bahamas

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSearching for Dayan Jayatilleka

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWhy are SL universities’ positions low in world ranking indices?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoBIA thrown into turmoil as foreign firm handles on-arrival visa counter

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank breaks new ground in Sri Lanka enabling Alipay QR payments for merchants

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA collection of stories by Kamala Wijeratne