Opinion

Materialism vs Buddhism

By Dr. Justice Chandradasa Nanayakkara

We live in a world dominated by materialism. Acquisition of things has become the core of our existence. Status and wealth are given so much importance. People like to flaunt their wealth and other material objects, such as new vehicles, trendy clothes, houses, modern gadgets and even lovely holidays spent in faraway exotic places. In a materialistic society, people are more inclined to demonstrate their status through visible materialistic consumption. They constantly try to attract the attention and recognition of others.

Contemporary materialism as a mindset is a part of a long history that established its roots in the 20 th century. Briefly, materialism is the desire for wealth and material possessions with little interest in ethical or spiritual matters. The Oxford Dictionary defines materialism as “a tendency to consider material possessions and physical comfort as more important than spiritual values”. Materialists have a general tendency to define success in terms of the amount and quality of one’s possessions. In a purely materialistic society people tend to act with a perverted sense of values and fling themselves into the blind unbridled pursuit of wealth, power and material possessions. There is a misconception that the wealthier you are, the happier you will be. Materialistic people tend to be more competitive and constantly compare themselves to others. Materialism is closely linked to consumerism, which is associated with the use of strategies and other techniques that encourage customers to expand their needs and desires.

People who live in a materialistic society, are constantly and continually influenced by advertisements on social media tempting them to buy products and other ostentatious articles, which sometimes they do not really need. Advertisers relentlessly attempt to hook unsuspecting customers with the sole objective of selling their products regardless of their impact on them. The higher the exposure to advertisements on television and other social media platforms, the more materialistic the individual’s values become. Further, widespread use of online shopping and e-commerce in the last few decades have also deeply aggravated the materialistic mindset in people. Although, in a materialistic society people tend to buy things far in excess of their needs, yet they seem to be less satisfied with almost everything.

Materialism conveys the idea that wealth and possession of other tangible things are the root of happiness and wellbeing of people. There are certain self-centered and negative qualities generally associated with materialism such as lack of empathy, jealousy extravagance, indifference, narcissism and lack of concern for others and detachment from personal relationships. Moreover, materialism is associated with low levels of pro social behaviour, more ecologically destructive behavior, poor management of personal finances and debt and also health problems such as depression, mental illness, drug dependence etc.

Human beings are slaves to their desires, particularly material desires. Most of them have at one time or another experienced an all-consuming desire for material objects. A desire so strong that it seems like they could not possibly be happy without buying those particular objects. Yet when they give in to this impulse they often find themselves frustrated and empty. As human beings they all tend to lean towards materialism in all their actions. Their desires are insatiable, limitless and inexhaustible and their personal lives are governed by the assumption that gratification of the craving is the only way to happiness. If we deeply examine the lives of people who are obsessed with materirilistic desires whether it be sensual, wealth power or possession we would find in their heart of hearts they enjoy very little contentment and happiness. Happiness derived from material possession is short lived.

Against this background, questions arise whether teachings of the Buddha are compatible with the secular philosophy of materialism which primarily focuses on the importance of physical matter.

Some are of the view that the teachings of the Buddha are not compatible with the concept of materialism and they think they are two opposittes and two irreconcilable extremes. They think to lead a life in conformity with Buddhist teachings in a materialistic society, one has to abandon and reject all enjoyment of material comfort and things. The Buddha was concerned with the material welfare of laity as much as with their spiritual advancement. He declared leading a materialistic life does not necessarily disqualify a person from following a Buddhist spiritual path. He did not stipulate that a person should withdraw from social and civilian obligations and lead an ascetic life. Further, he did not discourage laymen from mundane happiness. He simply declared that mundane happiness should be obtained in keeping with Buddhist moral and spiritual principles. Buddhism recommends only that wealth and materialistic possessions should be acquired by right livelihood and be utilised in meaningful ways for the benefit of oneself and others. Moreover, Buddha did not condemn the acquisition of wealth nor did he prohibit a person from having material possessions, on the contrary, he expressly encouraged hard work to gain wealth so that he will be able to live his normal life and do meritorious deeds. What matters in Buddhist context is that one can enjoy the pleasure that possession of material things brings but without attachment. He only recommended a life regulated by moral values aimed at the cultivation of wholesome qualities of mind. It should be understood that even in a totally hardened materialistic person there is deep within his mind a religious dimension. Spiritual and materialistic lives are not totally incompatible.

Buddhism is not against owning possessions nor is it against consumption altogether. Only when human beings are overly attached to wealth, does wealth become a cause of disaster. As long as one does not possess any attachment or cravings, living in a plush house and dressing in gorgeous, trendy clothes and partaking of exquisite delicacies will not be an issue in Buddhism.

However, material progress devoid of any spiritual or moral foundation would be of no avail. What the Buddha discouraged was attachment to wealth and the misconception that wealth alone could bring happiness. It should be understood that one day we all have to give up our wealth, power and position and leave behind what we have gathered during our lifetime. There is nothing that is permanent in life be it goodness, wealth, health and happiness. This is the natural law of impermanency. Losing all what we have acquired is inevitable but the pain that accompanies the losing of what we have acquired is proportional to the force of attachment, as strong attachment brings much suffering little attachment brings little suffering and no attachment brings no suffering. Therefore, all acquisition of wealth material possessions and power should be done with a clear comprehension of impermanent.

Human being is a complex entity that has a diversity of needs, which must be met to ensure his happiness and wellbeing. They need certain basic needs such as food, clothing dwelling, for their sustenance These basic needs are simple for a person who is not obsessively materirilistic in his outlook and pursuing the Right Livelihood. But our action getting those basic needs should not be motivated by craving. Buddhism teaches us that leading a life fueled by materialism will never make us happy. Buddha declared “It is not life and wealth and power that enslave men, but the clinging to life and wealth and power”

Buddhism as one of the major religions of the world promotes the philosophy of minimalism in the lifestyle. It is an approach to life epitomised by simplicity and sparseness. One of the Buddhist principles that underlie minimalism as a lifestyle is found in the Second Noble Truth which describes the cause of suffering as craving we suffer because of our cravings and our attachments A central aspect of minimalism is the application of this teaching.

It is important that we as Buddhist should diverge from the destructive materialistic mindset, to one that favours more sustainable form of happiness.

Real solution to our economic and financial problems does not lie completely in putting our trust in an economic theory that promotes multiplication of wants in materialistic world. Any economic and social policy should be grounded firmly from start to finish by ethical norms. An economic policy which runs counter to the dhamma and condone unethical behaviour is bound to bring about widespread misery and suffering.

Today, those who enjoy the most abundant wealth, who exert greatest power who revel in luxuriant pleasure, suffer. They live on the edge of despair. Although in the affluent societies people enjoy a high standard of living in terms of material goods and services inward quality of their lives does not represent a commensurate level of improvement. as materialistic outlook has led to erosion of higher spiritual dimension of life.

For example, the United States is a highly developed country with a free market economy and has the world’s largest nominal GDP and wealth. It enjoys one of the highest gross domestic products per capita in the world. However, its crime rate is one of the highest in the world. Millions of elderly people are negligected by their children and die of loneliness in retirements homes. Domestic violence, child abuse and drug addiction, gun culture are some of the major problems with which the government has to grapple with.

Right understanding in the eighth path is the foundation for developing a proper sense of values. Without right understanding our vision is dimmed and all our efforts will be misguided and misdirected. We operate with a perverted sense of values and pursue blind and unbridled pursuit of wealth, power and possession.

Opinion

A puppet show?

After jog for the camera, wearing shorts in Jaffna, thanks to the freedom gained by the country being liberated from the clutches of the Tigers by the valiant efforts led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, President Anura Kumara Dissanayaka, said: “Some come past Sri Maha Bodhi and other Buddhist temples all the way to Jaffna to observe Sil, not to spread compassion but hatred.” When the need of the hour is reconciliation what an outrageous statement that was, to be made by the head of state! Will he say that the people of the North and the East bypass many Kovils straddling the area and come to Kataragama to spread hate? Probably not! His claim has become a hot topic of conversation.

Having lost a majority of the votes garnered from the North at the presidential and parliamentary elections, to the Tamil nationalist parties at the local government elections, President Dissanayake’s claim may well have been a pitiful attempt to recover lost ground in the North. But at what cost?

It all started with AKD’s refusal to refer to those brave service personnel who saved the unity and the integrity of the country as Rana Viruwo. Interestingly, the most devastating rebuke for this came from a Tamil MP, who is an avowed admirer of Prabhakaran, stating in Parliament that a Sinhala Rana Viruwa saved his life when he was about to be washed off in the flood waters resulting from Cyclone Ditwah. He teased the government by asking in ‘raw’ Sinhala Ei umbalata lejjada unta Rana Viruwo kiyanna? (Are you shy to call them war heroes?)

In addition to slinging mud at MR and harassing service personnel, there is no doubt whatsoever that AKD’s government is trying to harass any Tamil politicians who helped eradicate the Tigers. This fact is borne out by the treatment meted out to Douglas Devananda. Shamindra Ferdinando has explained this in his article, “EPDP’s Devananda and missing weapons supplied by Army” (The Island, 7 January).

NPP ministers publicly insult Buddhist monks, but whenever they are in trouble, they rush to Kandy to meet the Maha Nayakas, the latest being Harini’s visit. Instead of admitting the mistake and trying to make amends, the government went on, until it realised the futility in trying to justify the ‘Buddy’ episode. Excuses given by Harini to the Maha Nayakas, to say the least, were laughable. She had the audacity to say that though the questionable web link was printed in the textbook there were no instructions to click on it! She may continue as Prime Minister but can anyone who does not know what to do with a link or who is trying to encourage ten-year-olds to have e-buddies when the rest of the world is heading towards banning 16-year-olds from social media, continue to be the Minister of Education?

Number of MOUs/pacts signed with India, including defence, have not yet been disclosed even to Parliament. The Cabinet Spokesman once stated that the contents of those MOUs/pacts could not be divulged without the consent of India. Interestingly, we have had very frequent visits from VVIP politicians and top government officials from India, some at very short notice. One of them referred to these as ‘usual’ ones! However, what is unusual is that a party that shed a lot of blood of Sri Lankans for even selling ‘Bombay’ onions, is now in government and seems under Indian command. Perhaps, its transformation occurred when India sponsored a visit by AKD in early 2024, which helped him secure the presidency. Among the NPP’s election pledges, the most touted one was to reveal the mastermind behind the Easter Sunday attacks. It has been alleged in some quarters that India was behind the attacks. The NPP government’s silence about this speaks volumes!

It has transpired recently that it was Indian High Commissioner Gopal Baglay who pressured Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena in July 2022 to take over the presidency after the elected President was toppled by protesters, but many believe that it was a joint effort by the Indian HC and the ‘Viceroy’ who just left, after an overstay! It is an illegal act as pointed out in the editorial “Conspiracy to subvert constitutional order” (The Island, 22 January) and may be investigated by a future government, if elections are not postponed forever!

We seem to be watching a puppet show where many puppeteers outside are pulling the strings! Are we paying the price for electing a bunch of inexperienced politicians?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana ✍️

Opinion

Remembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

Salute to a brave father-son

Cedric Martenstyn was a very affluent man. He owned a house in Colombo 7, valuable properties throughout the country, vehicles / speed boats and ran the lucrative business of importing Johnson and Evinrude Outboard Motors (OBM) and sold them to local fishermen and businessmen.

Cedric was the local agent for the OBMs, which were known for reliability and after-sales service, and among his customers were humble fishermen. He was fondly known as Sudu Mahattaya “(white Gentleman) by humble fishermen and he would often travel in his double cab across the country to meet his customers and solve their problems.

He had a loving wife and children. He was an excellent scuba diver, member of Sri Lanka Navy Practical Pistol Firing team and his knowledge of wildlife and reptiles was amazing.

A member of the Dutch Burgher community of Sri Lanka, he was a true patriot, who volunteered to protect country and people from terrorists. An old boy of S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, he was an excellent sportsman.

The founding father of Sri Lanka Army Commando Unit, Colonel Sunil Peris, was his classmate at S.Thomas’.

I first met Cedric when I was a very junior officer at Pistol Firing Range at Naval Base, Welisara. I helped him catch a poisonous snake in the Range. I think he carried that snake home in a bottle! That was the type of person Cedric was!

We became very close friends as we both loved “guns and fishing rods”. His experience and tactics in angling helped me catch much bigger Paraw (Trevallies) in the Elephant Rock area at the Trincomalee harbour. He was a dangerous man to live with at Trincomalee Naval Base wardroom (officers’ mess), because he had various live snakes kept in bottles and fed them with little frogs!

Even though he was a keen angler, he was keen to conserve endangered species both on land and in water. He spent days in Horton Plains and the Knuckles Mountain Range streams to identify freshwater species in Sri Lanka. Did you know there is an endangered freshwater fish species he found in Horton Plains and Knuckles Mountain Range has been named after him?

Feeding of snakes was an amusement to all our stewards at the wardroom at that time! They all gathered and watched carefully what Cedric was doing, keeping a safe distance to run away if the snake escaped. Our Navy stewards dare to enter Cedric’s cabin (room) at Trincomalee wardroom (officers’ mess), even keeping his tea on a stool outside his cabin door. One day pandemonium broke in the officers’ mess when Cedric announced that one snake escaped! We never found that snake, and that was the end of his hobby as the Commander Eastern Naval Area, at that time, ordered him to ” get rid of all snakes! Sadly, Cedric released all snakes to Sober Island that afternoon.

Cedric was a volunteer Navy officer, but still joined me (he was 47 years old then) to help SBS trainees (first and second batch) on boat handling and OBM maintenance in 1993, when I raised SBS. It was exactly 31 years ago!

The Arrow Boat

Being an excellent speed boat race driver and boat designer, he prepared the blueprint of the first “18-foot Arrow Boat” and supervised building it at a private Boat Yard in 1993. This 18- foot Arrow Boat was especially designed to be used in the shallow waters of the Jaffna lagoon, fitted 115 HP OBMs, and with two weapons he recommended; 40mm Automatic Grenade Launcher (AGL) and 7.62×51 mm General Purpose Machine Guns (GPMGs). In no time, we had highly trained and highly motivated four SBS men on board each Arrow Boat at Jaffna lagoon, and they were very effective.

Same hull (deep V hull) developed during the tenure of Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda, as Commander of the Navy, by Naval architects, with knowledge-gained through captured LTTE Sea Tiger boats, designed 23- foot Arrow Boats and implemented the “Lanchester Theory” (theory of battle of attrition at sea in littoral sea battles) to completely nullify LTTE’s superiority which it had gained with small craft and deadly suicide boats.

Thank you, the Admiral of the Fleet for understanding the importance of Arrow Boat design and mass production at our own boatyard at Welisara. Karannagoda, under whom I was fortunate to serve as Director Naval Operations, Director Maritime Surveillance and Director Naval Special Forces during the last stages (2006/7) of the Humanitarian Operations, always used to tell us “You cannot buy a Navy- you have to build one”! Thank you, Sir!

Cedric craft display at Naval Museum, Trincomalee

The Hero he was

When I was selected for my Naval War Course (Staff Course) conducted by the Pakistan Navy Staff College at Karachi, Pakistan, (now known as Pakistan Navy War College relocated at Lahore), Cedric took over the command (even though he was a VNF officer) as Commanding Officer of SBS.

Being one of the co-founders of this elite unit, he was the most suitable person to take over as CO SBS. He was loved by SBS officers and sailors. They were extremely happy to see him at Kilali or Elephant Pass, where SBS was deployed during a very difficult time of our recent history – fighting against terrorists during the 1996-97 period.

Motivated by father’s patriotism, his younger son, Jayson, who was a pilot working in the UK at that time, came back to Sri Lanka and joined the SLAF as an volunteer pilot to fly transport aircraft to keep an uninterrupted air link between Palaly (Jaffna) and Ratmalana (Colombo). Sometimes Jayson flew his beloved father on board from Palaly to Ratmalana. Cedric was extremely happy and proud of his son.

Tragically, young Jayson was killed in action in a suspected LTTE Surface-to-Air missile attack on his aircraft. Cedric was sad, but more determined to continue the fight against LTTE terrorists. He would also lead the rescue and salvage operation to identify the aircraft wreckage his son flew in. The then Navy Commander advised him to demobilise from VNF and look after his grieving family or join Naval Operations Directorate and work from Colombo which he vehemently refused. When I called him from Pakistan to convey my deepest condolences, he said, he would look after the “SBS boys”, he had no intention of leaving them alone at that difficult hour of our nation. That was Cedric. He was such a hero—a hero very few knew about!

The young officers, and sailors in SBS were of his sons’ age, and Cedric would not leave them even when he was facing a personal tragedy. He was a dedicated and courageous person.

Scientific name: Systomus Martenstyni

English name : Martenstyn’s Barb

Local name: Dumbara Pethiya

Sadly, like many who served our nation and stood against terrorists, Cedric would go on to be considered Missing In Action (MIA) following a helicopter crash off the seas of Vettalikani with Lt. Palihena (another brave SBS officer- KDU intake). He was returning to Point Pedro after visiting the SBS boys at Elephant Pass, Jaffna.

Cedric and his son, Jayson, will go down in history as a brave father-son duo who paid the supreme sacrifice for the motherland. MAY THEY REST IN PEACE ! Salute!

Commander Martenstyn was considered missing in action (MIA) on 22 January 1996 in the sea off Vettalaikerni, while returning to Palaly Air Force Base in an SLAF helicopter when it was lost to enemy fire. He was returning from visiting an SBS detachment in Elephant Pass near the Jaffna Lagoon. Considering his contribution to the war effort, his gallentry and valour in fighting the enemy, and his steadfast service to the Sri Lanka Navy in manufacturing Arrow Boats, and training the SBS, all SLN Arrow Boats were renamed ‘Cedric’ on his 70th Birthday.

(The writer is former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of The Navy, and former Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd.)

By Admiral Ravindra

C Wijegunaratne

(Retired from Sri Lanka Navy)

Former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of the Sri Lanka Navy,

Former Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan

Opinion

History of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

According to legend, St. Sebastian was born at Narbonne in Gaul. He became a soldier in Rome and encouraged Marcellian and Marcus, who were sentenced to death, to remain firm in their faith. St. Sebastian made several converts; among them were master of the rolls Nicostratus, who was in charge of prisoners, and his wife Zoe, a deaf mute whom he cured.

Sebastian was named captain in the Roman army by Emperor Diocletian, as by Emperor Maximian when Diocletian went to the east. Neither knew that Sebastian was a Christian. When it was discovered that Sebastian was indeed a Christian, he was ordered to be executed. He was shot with arrows and left to die but when the widow of St. Castulas went to recover his body, she found out that he was still alive and nursed him back to health. Soon after his recovery, St. Sebastian intercepted the Emperor; denounced him for his cruelty to Christians and was beaten to death on the Emperor’s order.

St. Sebastian was venerated in Milan as early as the time of St. Ambrose. St. Sebastian is the patron of archers, athletes, soldiers, the Saint of the youths and is appealed to protection against the plagues. St. Ambrose reveals that the parents that young Sebastian were living in Milan as a noble family. St. Ambrose further says that Sebastian, along with his three friends, Pankasi, Pulvius and Thorvinus, completed his education successfully with the blessing of his mother, Luciana. Rev. Fr. Dishnef guided him through his spiritual life. From his childhood Sebastian wanted to join the Roman army. With the help of King Karnus, young Sebastian became a soldier and within a short span of time he was appointed as the Commander of the army of King Karnus. The Emperor Diocletian declared Christians the enemy of the Roman Empire and instructed judges to punish Christians who have embraced the Catholic Church. Young Sebastian, as one of the servants of Christ, converted thousands of other believers into Christians. When Emperor Diocletian revealed that Sebastian had become a Catholic, the angry Emperor ordered for Sebastian to be shot to death with arrows. After being shot by arrows, one of Sebastian supporters, Irane, treated him and cured him. When Sebastian was cured he went to Emperor Diocletian and professed his faith for the second time disclosing that he is a servant of Christ. Astounded by the fact that Sebastian is a Christian, Emperor Diocletian ordered the Roman army to kill Sebastian with club blows.

In the liturgical calendar of the Church, the feast of the St. Sebastian is celebrated on the 20th of January. This day is indeed a mini Christmas to the people of Kandana, irrespective of their religion. The feast commenced with the hoisting of the flag staff on the 11th of January at 4 p.m. at the Kandana junction, along the Colombo-Negombo road. There is a long history attached to the flag staff. The first flag staff, which was an areca nut tree, 25 feet tall, was hoisted by the Aththidiya family of Kandana, and today their descendants continue hoisting of the flag staff as a tradition. This year’s flag staff, too, was hoisted by the Raymond Aththidiya family. Several processions, originating from different directions, carrying flags, meet at this flag staff junction. The pouring of milk on the flag staff has been a tradition in existence for a long time. The Nagasalan band was introduced by a well-known Jaffna businessman that had engaged in business in Kandana in the 1950s. The famous Kandaiyan Pille’s Nagasalan group takes the lead, even today, in the procession. Kiribath Dane in the Kandana town had been a tradition from time immemorial.

According to available history from the Catholic archives and volume III of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka, the British period of vicariates of Colombo, written by Rev. Ft. Vito Perniola SJ, in 1806, states that the British government granted the freedom of conscious and religion to the Catholics in Ceylon and abolished all the anti-Catholic legislation enacted by the Dutch.

The proclamation was declared and issued on the 3rd of August 1796 by Colonel James Stuart, the officer commanding the British forces of Ceylon stated “freedom granted to Catholics” (Sri Lanka national archives 20/5).

Before the Europeans, the missioners were all Goans from South India. In the year 1834, on the 3rd of December, XVI Gregory the Pope, issued a document Ex Muwere pastoralis ministeric, after which the Ceylon Catholic Church was made under the South Indian Cochin diocese. Very Rev. Fr. Vincent Rosario, the Apostolic Vicar General, was appointed along with 18 Goan priests (The Oratorion Mission in Sri Lanka being a history of the Catholic Chruch 1796-1874 by Arthur C Dep Chapter 11 pg 12). Rev Fr. Joachim Alberto arrived in Sri Lanka as missionary on the 6th of March 1830 when he was 31 years old and he was appointed to look after the Catholics in Aluthkuru Korale, consisting Kandana, Mabole, Nagodaa and Ragama. There have been one Church built in 1810 in Wewala about three miles away from Kandana. The Wewala Chruch was situated bordering Muthurajawela which rose to fame for its granary. History reveals that the entire area was under paddy cultivation and most of them were either farmers or toddy tappers. History further reveals that there has been an old canal built by King Weera Parakrama Bahu. Later it was built to flow through the Kelani River, and Muthurajawela, up to Negombo, which was named as the Dutch Canal (RL Brohier historian). During the British time this canal was named as Hamilton Canal and was used to transport toddy, spices, paddy and tree planks of which tree planks were stored in Kandana. Therefore, the name Kandana derives from “Kandan Aana”.

Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto purchased a small piece of land, called Haamuduruwange watte, at Nadurupititya, in Kandana, and put up a small cadjan chapel and placed a picture of St. Sebastian for the benefit of his small congregation. In 1837, with the help of the devotees, he dug a small well where the water was used for drinking and bathing and today this well is still operative. He bought several acres of land, including the present cemetery premises. Moreover, he had put up the Church at Kalaeliya in honour of his patron St. Joachim where his body has been laid to rest according to his wish of the Last Will attested by Weerasinghe Arachchige Brasianu Thilakaratne. Notary Public, dated 19th July 1855. The present Church was built on the property bought on the 13th of August 1875 on deed no. 146 attested by Graciano Fernando. Notary Public of the land Gorakagahawatta Aluthkuru Korale Ragam Pattu in Kandana within the extend ¼ acre from and out of the 16 acres. According to the old plan number 374 made by P.A. H. Philipia, Licensed surveyor on the 31st of January 195, 9 acres and 25 perches belonged to St. Sebastian Church. However, today only 3 acres, 3 roods and 16.5 perches are left according to plan number 397 surveyed by the same surveyor, while the rest had been sold to the villagers. According to the survey conducted by Orithorian priest on the 12th of February 1844 there were only 18 school-going Catholic students in AluthKuru Korale and only one Antonio was the teacher for all classes. In 1844 there was no school at Kandana (APF SCG India Volume 9829).

According to Sri Lanka National Archives (The Ceylon Almanac page 185) in the year 1852 there were 982 Catholics Male 265, female 290, children 365, with a total of 922. According to the census reports in 2014, prepared by Rev. Ft. Sumeda Dissanayake TOR, the Director Franciscan Preaching group, Kadirana Negombo a survey revealed that there are 13,498 Catholics in Kandana.

According to the appointment of the Missionaries in the year 1866-1867 by Bishop Hillarien Sillani, Rev. Fr. Clement Pagnani OSB was sent to look after the missions in Negoda, Ragama, Batagama, Thudella, Kandana, Kala Eliya and Mabole. On the 18th of April 1866, the building of the new Church commenced with a written agreement by and between Rec. Fr. Clement Pagnani and the then leaders of Kandana Catholic Village Committee. This committee consisted of Kanugalawattage Savial Perera Samarasinghe Welwidane, Amarathunga Arachchige Issak Perera Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Arachchige Don Isthewan Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Appuhamylage Elaris Perera Muhuppu, Padukkage Andiris Perera Opisara, Kanugalawattage Peduru Perera Annavi and Mallawa Arachchige Don Peduru Appujamy. The said agreement stated that they will give written undertaking that their labour and money will be utilised to build the new Church of St. Sebastian and if they failed to do so they were ready to bear any punishment which will be imposed by the Catholic Church.

Rev. Fr. Bede Bercatta’s book “A History of the Vicariate of Colombo page 359” says that Rev. Fr. Stanislaus Tabarani had problems of finding rock stones to lay the foundation. He was greatly worried over this and placed his due trust in divine providence. He prayed for days to St. Sebastian for his intercession. One morning after mass, he was informed by some people that they had seen a small patch of granite at a place in Rilaulla, close to the Church premises, although such stones were never seen there earlier, and requested him to inspect the place. The parish priest visited the location and was greatly delighted as his prayers has been answered. This small granite rock amount provided enough granite

blocks for the full foundation of the present church. This place still known as “Rilaulla galwala”. The work on the building proceeded under successive parish priests but Rev. Fr. Stouter was responsible for much of it. The façade of the Church was built so high that it crashed on the 2nd of April of 1893. The present façade was then built and completed in the year 1905. The statue of St. Sebastian, which is behind the altar, had been carved off a “Madan tree”. It was done by a Paravara man, named Costa Mama, who was staying with a resident named Miguel Baas a Ridualle, Kandana. This statue was made at the request of Pavistina Perera Amaratunge, mother of former Member of Parliament gatemuadliyer D. Panthi Jayasuirya. The Church was completed during the time of Rev. Fr. Keegar and was blessed by then Archbishop of Colombo Dr. Anthony Courdert OMI on the 20th of January 1912. In 1926, Rev. Fr. Romauld Fernando was appointed as the parish priest to the Kandana Church. He was an educationalist and a social worker. Without any hesitation he can be called as the father of education to Kandana. He was the pioneer to build three schools in Kandana: Kandana St. Sebastian Boys School, Kandana St. Sebastian English Girls School and, the Mazenod College Kandana. Later he was appointed as the Principal of the St. Sebastian Boys English School. He bought a property at Kandana, close to Ganemulla Road, and started De Mazenod College. Later, it was given officially to the Christian Brothers of Sri Lanka, by then Archbishop of Colombo, Peter Mark. In 1931, there were 300 students (history of De Lasalle brothers by Rev. Fr. Bro Michael Robert). Today, there are over 3,500 students and is one of the leading Catholic schools in Sri Lanka. In 1924, one Karolis Jayasuriya Widanage donated two acres to build De Mazenod College for its extension.

The frist priest from Kandana to be ordained was Rev. Fr. William Perera in 1904. With the help of Rev. Fr. Marcelline Jayakody, he composed the famous hymn “the Vikshopa Geethaya”, the hymn of our Lady of Sorrow.

The Life story of St. Sebastian was portrayed through a stage play called “Wasappauwa” and the world famous German passion play Obar Amargavewchi whichwas a sensation was initiated by Rev. Fr. Nicholas Perera. Legend reveals that in the year 1845 a South Indian Catholic, on his way to meet his relatives in Colombo, had brought down a wooden statue of St. Sebastian, one and half feet tail, to be sold in Sri Lanka. When he reached Kalpitiya he had unexpectedly contracted malaria. He had made a vow at St. Anne’s Church, Thalawila, expecting a full recovery. En route to Colombo, he had come to know about the Church in Kandana and dedicated to St. Sebastian. In the absence of the then parish Priest Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto, the Muhuppu of the Church, with the help of the others, had agreed to by the statue for 75 pathagas (one pahtaga was 75 cent). Even though the seller had left the money in the hands of the “Muhuppu” to be collected later, he never returned.

On the 19th of January 2006, Archbishop Oswald Gomis declared St. Sebastian Church as “St. Sebastian Shrine” by way of a special notification and handed over the declaration to Rev. Fr. Susith Perera, the Parish Priest of Kandana.

On the 12th of January 2014, Catholics in Sri Lanka celebrated the reception of a reliquary containing a fragment of the arm of St. Sebastian. The reliquary was gifted from the administrator of the Basilica of St. Anthony of Padua and was brought to Sri Lanka by Monsignor Neville Perera. His Eminence Malcolm Cardinal Ranjit, Archbishop of Colombo, accompanied by priests and a large gathering, received the relic at the Katunayake International Airport, and brought it to Kandana, led by a procession, and was enthroned at the St. Sebastian Shrine.

Rev. Fr. Srinath Manoj Perera, the present administrator of the shrine, and assistant Priest Rev. Fr. Asela Mario, have finalised all arrangements to conduct the feast of St. Sebastian in a grand scale.

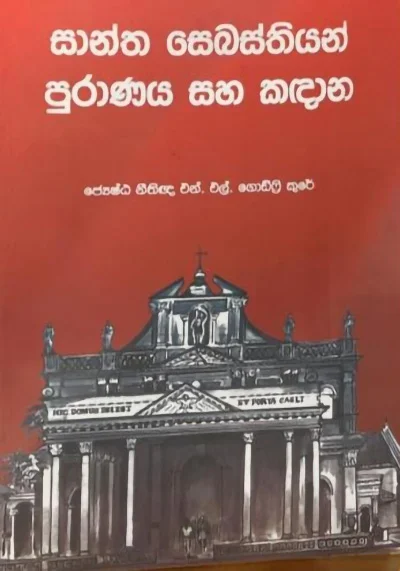

The latest book, written by Senior Lawyer Godfrey Cooray, named “Santha Sebastian Puranaya Saha Kandana” (The history of St. Sebastian and Kandana), was launched at De La Salle Auditorium, De Mazenod College, Kandana.

The Archbishop of Colombo His Eminence Most rev. Dr. Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith was the Chief Guests at the event.

The book discusses about the buried history of Muthurajawela and Aluth Kuru Korale civilisation, the history of Kandana and St. Sebastian. The author discusses the historical and archaeological values and culture.

158th Annual Feast of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine, Kandana, will be held on 20th of January 2026. On the 19th of January, Monday, Solemn Vespers were presided by His Lordship most Rev. Dr. Maxwell Silva Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo.

Festive High Mass will be presided by His Lordship Most Rev. Dr. J. D. Anthony, The Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo, on the 20th of January at 8pm.

By Godfrey Cooray

Senior Attorney -at -Law,

Former Ambassador to Norway and Finland

President, National Catholic Writers’ Association

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoWriting a Sunday Column for the Island in the Sun

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL