Opinion

Maria Montessori’s sway in children’s education

Women’s History Month begins on 01 March

The Italian educator and physician Maria Montessori (1870–1952) is best known for the teaching method that bears her name. She was also a lifelong pacifist, although historians tend to consider her writings on this topic as secondary to her pedagogy. In The Best Weapon for Peace: Maria Montessori, Education, and Children’s Rights, Erica Moretti reframes Montessori’s pacifism as the foundation for her educational activism, emphasising her vision of the classroom as a gateway to reshaping society. Montessori education offers a child-centred learning environment that cultivates students’ development as peaceful, curious, and resilient adults opposed to war and invested in societal reform.

Using newly discovered primary sources, Moretti examines Montessori’s lifelong pacifist work, including her ultimately unsuccessful push for the creation of the White Cross, a humanitarian organisation for war-affected children. Moretti shows that Montessori’s educational theories and practices would come to define children’s rights, once adopted by influential international organisations, including the United Nations. She uncovers the significance of Montessori’s evolving philosophy of peace and early childhood education, within broader conversations about internationalism and humanitarianism. (Published by the University of Wisconsin press)

Postscript: Montessori schools around the world, unlike those in Sri Lanka, educate children from toddlers through high school, using the Montessori method. This is mostly prevalent in Europe, South America and North America, including such countries as Canada and the United States.

Some famous Montessori students have been the founders of Google: Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the founder of Amazon: Jeff Bezos, Anne Frank the young girl who wrote, The Diary of Anne Frank, before the Nazis sent her to a death camp. Others have included the former co-owner of the Washington Post, Katherine Graham, and actresses Helen Hunt and Melissa Gilbert.

CHANDRA FERNANDO

Educational Consultant, USA

Opinion

How to write a research paper

Key Steps and Best Practices

BY Gamini Keerawella

Conducting research and writing a research paper are distinct yet interdependent exercises. In the Social Sciences, a single research project can yield multiple papers, each exploring different dimensions of the central inquiry. A well-executed research project does not automatically translate into a well-crafted research paper. Writing is an art—one that requires practice, patience, and a structured approach. Transforming research findings into a coherent, compelling, and readable paper demands adherence to established methodologies and best practices. Over time, researchers have identified key steps that capture best practices, ensuring clarity, logical flow, and academic integrity. This essay outlines these essential steps for effectively structuring and producing a research paper. However, this should not be taken as a rigid straitjacket; rather, it serves as only a guide to writing a research paper. Before writing your essay, it is essential to identify your main audience. Additionally, the structure of your research paper may require slight adjustments depending on where it will be presented. Many annual research conferences organised by Sri Lankan universities follow a rigid, standardised format, requiring you to fit your content accordingly. However, my focus here is to provide guidelines for writing research articles intended for research journals and the academic sections of newspapers, where writers have more freedom to develop their ideas and structure their content.

Title of Research Paper

The first step in writing a research paper is selecting an appropriate title to align with the scope and central argument of the paper. In turn, a well-crafted title serves as a guiding framework, helping to structure paper’s arguments effectively. When formulating a title, clarity and precision should be the primary focus. It is important to use clear, straightforward language and avoid jargon or overly complex terminology in title that might confuse readers. Additionally, the title should be concise—an excessively long title can dilute the focus, while an overly short one may lack essential details. A compelling title should capture the reader’s interest and encourage further exploration of the paper. Depending on the nature of the research, the title can be framed as a statement or a question, capable of stimulating curiosity and prompting engagement with the content.

Objective of the Paper

First and foremost, you must have a clear understanding of the paper’s objective(s). The next step in writing a research paper is clearly presenting the research question/issue that you are going to explore. If the issue is too broad, the paper may turn into a general essay; if too narrow, it may not give you necessary depth to develop a strong argument. Striking a balance is essential. This step is crucial as it distinguishes research essay from a general essay. A well-defined research problem provides direction for the study by establishing its scope—determining what aspects will be covered and what will be excluded. Rather than simply restating the central research problem, focus on identifying and refining a specific question that your paper aims to address. It is imperative that the research problem be clear, precise, and researchable, enabling systematic investigation and meaningful analysis. Additionally, it is essential to briefly explain the significance of the problem—why it is being raised, and its contribution to the existing body of knowledge. A well-defined research problem not only justifies the study but also provides a strong foundation for developing a compelling argument and drawing evidence-based conclusion

Concepts

When writing a research paper, it is essential to have a clear understanding of the analytical concept that forms the foundation of your argument. Analytical/theoretical concepts will help you to organise your evidence and develop your argument. The level of detail and the way you introduce this concept will depend on your target audience and the nature of your subject matter. Your research may either develop a new analytical framework or test the validity of an existing concept through empirical data. In either case, offering a concise overview of the core idea behind the concept is crucial. This helps establish a solid analytical foundation for your argument and ensures that readers can follow the reasoning that underpins your research. Providing such context also allows for a more meaningful engagement with the data and enhances the overall coherence of your study. Depending on your research focus and publication venue, you may briefly outline your data collection methods.

Scope/Parameters of the Paper

In a research paper, you are not supposed to cover every thing related to the topic. It is essential to clearly define the scope in alignment with the paper’s objectives, as this is fundamental to a focused and coherent analysis. The scope outlines the boundaries of the essay; what aspects will be covered and what will be excluded. This helps in maintaining clarity, avoiding unnecessary diversions, and ensuring that the study remains aligned with its intended purpose. The parameters vary according to the objective (research problem) and the subject mater of the paper. It is essential to have a clear idea of the extent to which the paper will examine its core themes, concepts, or issues. You need to decide whether the focus is theoretical, empirical, or policy-oriented or hybrid. Depending on the research it is better to indicate the period under study, whether it spans a specific historical timeframe. Clearly stating what aspects will not be covered—and justifying these exclusions—helps set realistic expectations for readers while acknowledging constraints such as data availability, methodological limitations, or thematic relevance. Defining the scope with precision ensures that the analysis remains structured and aligned with the core research questions.

Structure into Main Sections/Parts

Once you have precisely defined the scope of your paper and clarified the key concepts, the next crucial step is organising it into well-structured sections. Dividing your paper into clear parts strengthens its structure, enhances readability, and ensures logical argumentation. Outlining the main sections at the beginning helps guide the reader and sets clear expectations. The number of parts will depend on the scope of the paper. However, excessive segmentation can overwhelm the reader and disrupt coherence. It is essential to strike a balance, ensuring each section serves a distinct purpose without unnecessary fragmentation. Each section should logically build on the previous one, reinforcing the central thesis while maintaining clarity. A well-organised structure ensures that every section contributes meaningfully to the argument, enhancing both clarity and persuasiveness.

Subheadings

A key element of a research essay is the use of subheadings in major sections. Subheadings structure a research paper by breaking main sections into manageable parts, improving logical flow and guiding the reader through the content. Well-crafted subheadings enhance coherence by ensuring smooth transitions between ideas and maintaining a clear organisational hierarchy. They enhance the readability of the paper by providing a clear sense of what each subsection covers. To be effective, subheadings should be thoughtfully designed, directly connected to the main heading, and reflective of the paper’s structure. A strong subheading is both descriptive and aligned with the section’s content, improving clarity and readability. By using subheadings strategically, a research paper becomes more accessible, well organized, and engaging for the reader.

Building Argument

The most important aspect of a research paper is the construction of a clear and compelling argument. Unlike a general essay, which often serves a descriptive purpose, a research paper is fundamentally analytical and seeks to establish a position on a specific issue. This requires not only a logical structure but also a deliberate effort to develop an argument step by step.

A well-structured paper does not automatically make for a strong research paper. Structure serves as a framework for presenting an argument cogently, but it is the depth of reasoning, coherence of ideas, and evidence-based support that determine the strength of the argument. Without a clear argument, even the most well organised paper remains ineffective.

A research paper does not aim to cover every possible aspect of a subject. Instead, it requires a focused approach, identifying a specific issue or problem that is outlined at the outset. This issue forms the foundation of the argument, guiding the research and analysis. Building an argument is a step-by-step process. The argument must stem from a clearly defined research question or problem statement. Understanding previous explanations or theories related to the issue helps situate the argument within the broader discourse. The paper must take a clear stance—whether by introducing a new perspective or challenging an existing one. Logical reasoning, empirical data, and theoretical insights must be used to substantiate claims. The argument must be developed progressively, ensuring that each section builds upon the previous one in a logical sequence.

Presenting information alone does not constitute a research essay; rather, research is about constructing a well-reasoned argument. Whether by advancing a new explanation or critically engaging with existing ones, argumentation lies at the heart of scholarly inquiry. A structured approach enhances clarity, but the true strength of a research paper depends on the depth of its argument and the rigor of its analysis. Research does not always require formulating an entirely new argument; at times, critically examining and questioning prevailing explanations drive scholarly progress. Challenging an established thesis can pave the way for academic breakthroughs.

Organising Evidence

The strength and validity of an argument depend on how effectively one presents evidence to support it. Organizing evidence in a coherent manner is, therefore, a fundamental aspect of a research essay. Without sufficient and well-structured evidence, mere interpretation risks being perceived as opinionated rhetoric rather than rigorous academic analysis. Conversely, evidence without interpretation remains sterile and directionless. A well-balanced integration of evidence and interpretation is the hallmark of sound scholarship.

Beyond the mere presence of evidence, its organisation and presentation are equally crucial in strengthening an argument. In critically examining and presenting evidence, two key factors must be considered: authenticity and relevance. Authenticity ensures that the evidence is credible and verifiable, while relevance determines its applicability to the specific focus of the paper. The relevance of evidence is contingent on the research question; therefore, selecting appropriate supporting materials is essential.

Relying on a single piece of evidence is a novice mistake, as it weakens the foundation of an argument, leaving it vulnerable to scrutiny. While a primary or principle piece of evidence may serve as the central pillar of the argument, it must be substantiated with supplementary and corroborative evidence. This layered approach not only reinforces the argument but also demonstrates a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

Additionally, presenting counter-evidence—evidence that supports opposing interpretations—is an effective scholarly practice. Engaging with alternative explanations and refuting them through critical analysis enhances the credibility of the argument, showcasing a well-rounded and intellectually rigorous approach. A research essay, therefore, is not merely about advocating a viewpoint but about engaging with evidence in a nuanced and methodical manner to construct a compelling, defensible argument.

Language Clarity

Language is the primary vehicle for communicating structured thoughts and research findings. The clarity, precision, and coherence of writing directly impact how effectively arguments are conveyed and understood. A well-articulated argument, supported by clear and logical reasoning, strengthens the credibility of scholarly work. Conversely, ambiguity, redundancy, or poor organisation can undermine even the most compelling research.

In academic discourse, language is not just a tool but also a benchmark for evaluating scholarly work. Clarity and precision in writing are crucial for publication, as journals expect adherence to strict linguistic and stylistic standards. Academic writing defined by its formal structure, evidence-based reasoning, and objective tone, demands conciseness and readability. Frugal word use prevents redundancy and sharpens arguments, ensuring ideas remain clear and impactful.

For non-native English speakers, writing in English demands careful attention to linguistic accuracy and coherence. Since English is not our first language, we must be especially mindful of grammar, vocabulary, and syntax to ensure precision and professionalism. Good writing is, at its core, the art of rewriting. The process of drafting, revising, and refining is indispensable. Thorough editing before submission is essential to meet academic standards and effectively convey the intended message

Referencing in Academic Writing

Referencing is a crucial component of academic writing. It ensures the integrity of scholarly work by acknowledging previous research and writings. Proper referencing not only upholds academic honesty but also helps to avoid plagiarism, which is considered intellectual theft. Presenting someone else’s ideas, arguments, or written sections as your own without proper acknowledgment constitutes plagiarism, a serious ethical and academic offense.

There are two primary methods of referencing: direct quotations and footnotes/endnotes. A direct quotation involves using the exact words from a source to substantiate or support an argument. When incorporating direct quotations into your writing, they must be enclosed in quotation marks and followed by a relevant citation. In some cases, direct quotations can also be used to present an opposing argument before refuting it. However, excessive reliance on direct quotations should be avoided, as academic writing values analysis and synthesis over mere reproduction of existing material. In some instances, rather than quoting directly, you may need to paraphrase a long section from another source to maintain conciseness and clarity. Paraphrasing involves restating the ideas of others in your own words while preserving their original meaning. Even when paraphrasing, it is essential to provide a reference to the source to give due credit to the original author.

It is important to note that commonly accepted facts and general truths do not require citations. These include widely known historical dates, scientific laws, and universally acknowledged principles. However, when in doubt, it is always best to provide a citation to maintain academic credibility.

There are several established citation styles used in academic writing, including APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), and Chicago style. The choice of citation style depends on the academic discipline and institutional guidelines. Regardless of which citation style you follow, it is important to be consistent and avoid mixing different styles within a single document.

Conclusion

A conclusion serves as the logical summation of a paper, bringing the discussion to a meaningful close. While there is no universal formula, its structure and content depend on the nature of the essay. The primary purpose is to address the central research question or issue posed at the outset, offering a final perspective based on the arguments and evidence presented. Rather than summarizing every point, the conclusion should reinforce the most significant arguments supporting the thesis, ensuring clarity without redundancy. It is not the place to introduce new points, counterarguments, or evidence but should build on the existing discussion to provide a sense of closure. While it does not introduce new arguments, it can briefly suggest directions for future research, especially if there are unresolved questions or broader implications. A well-structured conclusion leaves a lasting impact, reinforcing key insights while maintaining logical coherence.

Bibliography

A bibliography is an essential component of any research paper, providing a comprehensive list of the sources that contributed to the development of the argument. It serves multiple purposes, including giving credit to original authors, ensuring transparency, and allowing readers to verify and further explore the sources used.

If you relied on specific databases to locate sources, these should be mentioned, especially if they played a key role in shaping your research. This helps demonstrate the depth of your literature review and the credibility of your sources. Every source that appears in footnotes or endnotes must be included in the bibliography. This ensures consistency and proper acknowledgment of the works that directly informed your study. Any book, article, or document from which you have taken direct quotes or paraphrased ideas should be listed in the bibliography. This is crucial for maintaining academic integrity and avoiding plagiarism. As with references, there are three main bibliography styles, and the chosen style must align with the one used for footnotes.

Beyond direct citations, it is useful to include major works that influenced your arguments. These may not be explicitly quoted but were significant in shaping your understanding of the subject. While compiling the bibliography, it is important to exercise selectivity and sound judgment. Not every source consulted needs to be included—only those that substantially contributed to the research. The goal is to maintain a focused, relevant, and authoritative list of references rather than an exhaustive or redundant compilation.

(This is based on a discussion the writer had with its Research Staff of the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS) on 13 June 2024.)

Opinion

How Chinese capacity building and USAID slush funds reveal ideological biases of our media

by Shiran Illanperuma

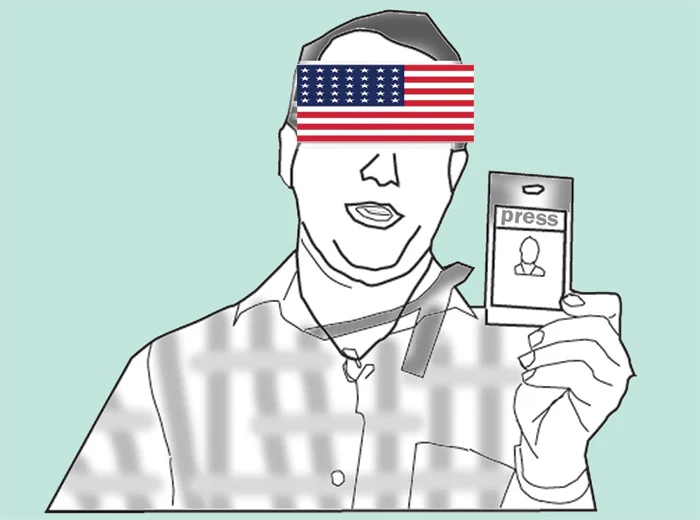

On 9 February, an article titled “Sri Lanka’s Undisclosed Pact with China Worries Media”, which was produced by the Union of Catholic Asian News, was carried in the Sunday Island. The article, which is full of speculation and insinuations, refers to the fact that several MOUs on capacity building are to be signed between Sri Lankan and Chinese state-owned media institutions.

One of the journalists quoted in the article raises concerns over Chinese media being “state-controlled”, while another suggested that partnerships with China would “compromise local media integrity and align it with foreign interests”. The irony is that this news comes in the wake of recent revelations by the Trump administration’s newly minted Department of Government Efficiency, that USAID spent 7.9 million US dollars to train Sri Lankan media.

It reveals a lot about biases in the media profession that partnerships with institutions from China, a rising Global South country that is constantly demonised by the Global North’s media monopolies, is seen as something dangerous and worth campaigning against. Meanwhile, the influx of millions of dollars from a US institution with deep roots in Cold War counterinsurgency and regime change operations is tacitly ignored or underplayed by the so-called defenders of free media.

Double standards

The double standard here is the implicit notion that training, grants, and technical support is ideologically and politically neutral (or positive even!) when the Global North does it. However, if China (or for that matter Russia, Iran or some other designated enemy of the Global North) does it, then of course it is immediately associated with mal-intent. This double standard is nothing but a modern-day manifestation of the trope of oriental despotism.

The easy retort to concerns over media partnerships with China is the simple observation that contemporary China does not seek to export its ideology and institutions. On the other hand, there is ample academic and journalistic evidence on the role of USAID in promoting US interests during the Cold War and beyond. Consider the example of Cuba, where The Guardian reported that the USAID funded a Twitter-like social network to promote content that would encourage the formation of “smart mobs” to “renegotiate the balance of power between state and society”.

There are other examples of USAID’s handiwork in the Global South. One is the case Dan Mitrione, a USAID contractor who worked for the agency’s Office of Public Safety Program in the 1960s. Mitrione oversaw the arming and training of scores of police officers under right-wing governments in Brazil and Uruguay. Mitrione would become notorious for training police officers in the art of torture, with classes on human anatomy, and electroshock and psychological torture.

Decolonising media

The Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin characterised imperialism through five key prongs of domination, one being the control over knowledge. This is why the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement pushed for a New World Information and Communication Order at the 19th Congress of UNESCO in 1970. This process culminated in the 1980 UNESCO report titled ‘Many Vices One World’ which was demonised as an attack on ‘free press’ by the US and UK. The report pointed out the alarming concentration and commercialisation of media, and recommended that countries strengthen their independence and self-reliance. This report so outraged the US that it was one of the reasons for its withdrawal from UNESCO in 1983.

What is striking is how little things have changed in the sphere of media and communications. With the fall of the Soviet Union and China’s shift away from attempting to export revolution, the entire edifice of the Global North’s media and communications monopoly built up during the Cold War continues basically unchallenged today. In addition to traditional media, there is now the dominance of new media companies such as Meta and X (formerly Twitter), which are private monopolies with opaque algorithms, access to sensitive user information from around the world, and close ties to the US government.

In the context of the Global North’s enduring hegemony over media and communication, South-South cooperation in media capacity building is something to be welcomed as a breath of fresh air.

Two traditions

Our understanding of the role of the media in society remains deeply Eurocentric, shaped as it is by the mythology of liberalism where so-called free (i.e. privately owned) media emerged as mouthpiece of the emerging capitalist class in their struggle against feudalism. However, the other side of this coin is the long history of private media in information warfare and suppressing working class and national liberation movements around the world.

The historical role of the media at the weaker links of capitalism is decidedly different. In many of these cases media emerged in the process of decolonisation, and in direct opposition to colonial pedagogy. In China for example, the Xinhua News Agency has its roots as the Red China News Agency in the Ruijin Soviet established by the Communist Party of China in Jiangxi in 1931. The agency was basically forged in fire during the Long March and, following establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, had to function more like an embassy due to the diplomatic isolation imposed by the Global North.

In Sri Lanka too, the true history of the media and its oligarchic owners is yet to be written. While there are certainly shortcomings in the way the nationalised media was managed, there is also an untold story of how important state-owned media was for the proliferation of popular education, health awareness programmes, and uplifting cultural programming for the masses.

In this latter tradition, the state-ownership of media is inseparable from the process of constructing a new society from the detritus of imperialism. How do we even begin to compare this ‘illiberal’ tradition of media that is deeply tied to projects of anti-colonial and socialist state building, to the ‘liberal’ media monopolies of the West which have constantly waged hybrid wars against sovereign states, from Cuba to Venezuela, Iraq to Libya, and yes, even Sri Lanka.

One need only look at recent bias reporting on the US-backed Israeli genocide in Gaza to understand the true face of the Global North’s liberal media monopolies.

(Shiran Illanperuma is a journalist and political economist. He is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a co-editor of Wenhua Zongheng: A Journal of Contemporary Chinese Thought. He is also a co-convenor of the Asia Progress Forum. He has an MSc in Economic Policy from SOAS, University of London.)

(Asia Progress Forum is a collective of like-minded intellectuals, professionals, and activists dedicated to building dialogue that promotes Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, development, and leadership in the Global South. They can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com).

Opinion

Revisiting Humanism in Education: Insights from Tagore – II

by Panduka Karunanayake

Professor in the Department of Clinical Medicine and former Director, Staff Development Centre,

University of Colombo

The 34th J.E. Jayasuriya Memorial Lecture

14 February 2025

SLFI Auditorium, Colombo

(Continued from 17 Feb.)

Tagore and humanism

Tagore was born to a wealthy Bengali family in British colonial India in the year 1861. This was a time of great social transformation in India, involving political, social, religious and literary movements. In his youth he saw the organisational structure that I described in its formative days, and immediately realised how it is unsuited for anything except the British colonial plans. In particular, he appreciated the strengths of traditional Indian education such as the gurukula, ashrama and tapovana systems, the value of the aesthetic sense to human growth and the role of the environment in our lives. He placed a huge importance on emotions and social values, and decried a materialistic or hedonistic approach to life. Always explaining his ideas through brilliant similes, he said: “The timber merchant may think that flowers and foliage are only frivolous decorations for a tree, but he will know to his cost that if these are eliminated, the timber follows them.”

But he also saw the value of the science and technology that the British were bringing in. He wasn’t a simplistic indigene fighting to chase the British out. He wanted to combine the good of both the old and the new, both India and the world. The best description that we can give of the man is call him a great harmoniser of ideas and an incorrigible optimist.

According to Subhransu Maitra, who is a well-known Indian intellectual who translates Bengali works into English, Tagore’s experimental journey on education lasted approximately fifty years, from the 1890s to the 1940s, and evolved through three phases. In the first phase, roughly from the 1890s to the 1910s, he thought of education as ‘freedom to learn,’ in contradistinction to the kind of straightjacketed rote-learning that British colonial education had introduced to India. He also fought for education in the mother tongue instead of English. This was the time Tagore set up the Brahmacharyashrama, a school for boys in Santiniketan. In the second phase, from the 1910s to the 1930s, he thought of education as ‘freedom from ignorance and want’ and as a powerful tool to emancipate humanity from poverty, superstition and suffering. This was the time when he set up the Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan, his version of a university, as well as Sriniketan, his effort at rural upliftment. And in the third phase, from the 1930s until his death in 1941, which was the time when Visva-Bharati was flourishing, he thought of education as an internationalist, humanist project or ‘freedom from bondage’, in contradistinction to nationalism. I will follow Tagore’s journey in this sequence, and at each stage try to highlight the lessons his educational philosophy gives us today.

But in toto, I feel that the common thread that runs through this journey is his commitment to humanistic education – a term that actually became popular only after his death, following the work of educational psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. So let me start by briefly explaining what humanistic education means.

Humanistic education is the application of the principles of humanism or humanistic philosophy to education. I am sure that many in this audience already know what humanism means, but bear with me when I try to explain it. I want to highlight the fact that humanism is not the same as some concepts with which it is often conflated – such as humanitarianism or humaneness or the humanities. In essence, humanism believes in the primacy of human agency, or the belief that humans are in charge of their own destinies; it is an Enlightenment idea that took agency away from divinity and placed it in the hands of the human being. (But of course, it is also very much part of some ancient philosophies.) But it identifies this agency as a responsibility both to oneself and one’s society, rather than as a libertarian licence. The ideal of humanism is human flourishing – not hedonism, nor any goal in the afterlife.

In humanism, human beings are considered independent, inherently good and capable of positive growth. One might look at these assumptions somewhat cynically – but it is hard to deny these qualities to a newborn child who has arrived on this world in all its innocence. As Tagore once famously said, “Every child comes with the message that God is not yet discouraged of man.”

As Ratna Navaratnam (1958) wrote in New Frontiers in East-West Philosophies of Education:

“Humanism takes as its dominant pattern the progress of the individual from helpless infancy to self-governing maturity…The child is put at the centre of the picture and the educator judges the truth of any theory and the success of any system, by the contribution it makes to the transformation of creative childhood into creative manhood.”

In humanistic education, several features can be identified:

* The student is given a free choice to decide what to study, how and for how long, within reason. As a result, the motivation to learn is intrinsic, rather than extrinsic goals such as exams, grades or certificates.

* The educational experience is left open, exploratory and self-driven. There is little or no emphasis on a curriculum, syllabus or what we today call ‘intended learning outcomes’.

* The setting for learning is safe. What the teacher does is provide the student with the resources to quench curiosity and play a supportive and facilitatory role, as a resource person and guide. There is no coercion, judgement, criticism or corporeal punishment.

* The learning environment focuses on both cognitive and emotional aspects of the learning experience; in other words, both ‘knowing’ and ‘feeling’ are considered valid and important to the learning process.

* And finally, at least a significant portion of the learning time is spent in contact with nature and the environment, rather than inside a classroom.

With that background, let me now turn to the three phases in Tagore’s journey in education.

Phase 1: ‘Freedom to learn’

Tagore was urged to experiment with education because he saw the unsatisfactory nature of schools, which he described as “…educational factories, lifeless, colourless, dissociated from the context of the universe, within bare white walls, staring like eyeballs of the dead…It provided information and knowledge for the intellectual growth and it neglected the aspects of human growth.”

Let me quote Tagore at length:

“The way we understand it, the word school means an education factory or mill of which the schoolmaster is a part. The bell goes off at half past ten and the mill begins to work. As the mill starts, the master also keeps spouting off. The mill closes at four o’clock. The master too, stops spouting and the students return home, their heads stuffed with factory-made lessons. Later, at the time of examinations, these lessons are evaluated and stamped.

“The advantage of factory production is that the products are exactly made to a standard and the products of different factories differ but little from one another. So, it is easy to grade them. But individuals differ a great deal from one another. Even an individual may not be the same from one day to the next.

“Even so, a man cannot get from machines what he gets from another man. A machine produces, it can’t give. It can supply oil, but it can’t light a lamp.”

Tagore’s journey was dedicated to find a suitable alternative to such factory-style education

You can see that he disliked uniformity and intellectual dominance in education, and he preferred freedom to do, experience, feel and learn. This is especially noteworthy today, because educational psychologists have since found the importance of the affective domain for learning: the so-called cognitive-emotional model of learning.

Importantly, the reason he liked a more active style of learning is not merely because it is better for assimilation or long-term memory – as we are accustomed to think today – but because it promoted the growth of individual talents and tastes and imparted a communitarian rather than an individualistic outlook to life.

He also preferred a more idyllic, rural setting to educate children, because he felt that cities and towns rob the students of their bonding with nature, which was necessary for the growing mind to grow freely, wholistically and strongly. This also included creating opportunities for social contact with the rural folk, and trying to help the villagers at least in small ways. So he was especially keen that school and society were welded together. That was his way of teaching two things: first, communication skills, and second, a sense of social service. It would be interesting to compare this to a similar local experiment: Dr C.W.W. Kannangara’s Handessa rural education scheme. (For an excellent account, see Gunasekara [2013].)

To Tagore, the school-society link was also necessary to impart moral virtues: “It is utterly futile to expect that the preaching of a few textbook precepts…at school will set right everything when countless varieties of dishonesty and perversity are destroying decency and taste every moment in today’s artificial life. This only results in different kinds of hypocrisy and insolent flippancy in the name of morality…”

All around us today, we can see how textbook-based teaching of virtues has led to hypocrisy among those who do wrong with impunity, flippancy among those who allow wrong to happen as if it is the norm, and cynicism among those who try to reconcile what they see with what they were taught in classrooms.

I am sure you will appreciate that some of Tagore’s humanistic ideas are being put into practice in pre-school and primary education even today, for instance following the teachings of Maria Montessori. In Sri Lanka, however, because of the bottleneck effect of exams, they are being throttled by the competitiveness and the rush to obtain certificates. This has enormous implications to our own education system. What Tagore taught us – by not judging learning through exams – is that if we had exams, much of what we expect students to learn would be ignored because they are not specifically assessed in the exams. The reason we want exams is because we want to compare student with student. But how can we compare student with student if each student is a unique person? What do we value greater: the comparison or the uniqueness? We must be careful when answering this question, because often it turns out that our answer is actually not that of the educationist but that of the industrialist, and not that of our society’s but that of the countries in the core of knowledge production.

Phase 2: ‘Freedom from ignorance and want’

This is perhaps the phase of his work that is hardest to pin down to a few fundamentals. But I will try.

To me, it appears that his first lesson is to tailor education to our own needs, rather than to import and transplant an educational system from elsewhere. (Tagore himself was, of course, warning about the dangers of blindly following the British system.) This is an excellent testament for what we today call contextual knowledge or conditional knowledge.

Looking around, I cannot help feel that this is such an important lesson for us too. I wish that as educationists we paid more attention to this. We cannot do so if we merely ask our teachers to do what international experts advise. We must study our own society, our own past practices and experiments, how they have succeeded or failed and why, what would work for us now and so on. Tagore said:

“Only when we are able to channel the current of education in our country through the numerous experiments of numerous teachers, it will become a natural thing of the country. Only then will we come across real teachers here and there, now and then. Only then a tradition, a succession of teachers will naturally follow. We cannot invent a particular educational system by labelling it as ‘national’. We can call ‘national’ only education of that kind which is being conducted in a variety of ways through a variety of endeavours by a variety of our countrymen…When a particular education system seeks to fasten a static ideal on to the country, we cannot call it ‘national’. It is communal and therefore, fatal to the country.”

To me, such a uniform education system is worse than communal – at best it would facilitate pedantry, at worst it could even facilitate totalitarianism and fascism.

Importantly, Tagore was keen to point out that when times change, the same energy needs to be spent on amending our systems and practices. In one speech he used a beautiful simile: he likened time to a river, and said that people who don’t change with changing times are like the people who would not change the position of the ferry even after the river has changed its position. He asked, How can they cross the river from the old ferry? This would be great advice for a country that still runs its educational system dictated to by policies that are over eighty years old.

The next crucial lesson is his trust in science and technology – but only appropriate technology – as well as his disdain for outdated traditions, superstitions and rituals. In this sense, he was remarkably modern. He said:

“When in the East we were busy calling upon the ghostbuster in case of disease, the astrologer to placate hostile planets in case of trouble, worshiping the goddess Sitala to ward off smallpox and similar epidemics, and practising home-grown black magic to get rid of enemies, in the West a woman asked Voltaire: ‘I have heard one can kill whole flocks of sheep by chanting a mantra?’ Voltaire replied: ‘It can certainly be done, but an adequate supply of arsenic along with it is also required.’ It cannot be absolutely ruled out that a modicum of faith in magic and the supernatural still persists in isolated pockets in Europe, but a trust in the efficacy of arsenic in this connection is almost universal there. That is why they can kill us whenever they want to and we are liable to die even when we do not want to.”

Tagore was wise enough to note that the British colonial government was actually quite keen to deny Indians this gift of science and technology. He pointed out that the colonial colleges and universities actually functioned with many constraints and limitations imposed by the colonial government. One of the main hopes that Tagore had in establishing Visva-Bharati was overcoming this. He knew that foreigners, both western and eastern, yearn to come to India to learn about her strong and vibrant achievements in the humanities. He welcomed them. In return, he also created space for Indians to come there and learn what the West had to teach – which, of course, was mainly science. This was the confluence of East and West that Tagore envisaged for Visva-Bharati. And I think that one

of the reasons why Visva-Bharati failed later on was that after Independence, India had an alternative, perhaps better way to forge ahead with science, when Jawaharlal Nehru set up the Indian Institutes of Technology. But I wonder whether Tagore’s plan in combining the strength in our humanities with the strength in science and technology of other lands within our educational system could still serve us here.

Tagore also created Sriniketan and its Institute of Rural Reconstruction, a rural upliftment

programme using what would later come to be called ‘appropriate technology’. This was not a

blind exercise in importing European machines and gadgets like washing machines or floor polishers. Instead, it was an attempt to solve the problems faced by the rural folk by the use of scientific knowledge and appropriate technological tools. It included components such as rural education, village sanitation, roving dispensaries, anti-malaria and child welfare schemes, cooperative societies, scientific

agriculture, experimental farming, dairy farming, weaving, tannery, smithy, carpentry and other

projects. It was designed to promote selfconfidence and self-help and eliminate ignorance and superstition among the villagers. As Tagore described his educational mission:

“Our centre of culture should not only be the centre of intellectual life of India, but the centre of her economic life as well. It must cultivate land, breed cattle, to feed itself and its students; it

must produce all necessaries, devising the best means and using the best materials, calling science to its aid. Its very success would depend on the success of its industrial ventures carried out on the co-operative principle; which will unite the teachers and students in a living and active bond of necessity. This will also give us a practical, industrial training, whose motive is not profit.”

When the time came for Tagore to send his son Rathindranath for higher education, he sent him not to Oxford but to learn agricultural science at Illinois: “Indians should learn to become better farmers in Illinois than better ‘gentlemen’ in Oxford”. Similarly, he sent the children of his relatives and friends, including his son-in-law, to learn other skills, such as scientific dairykeeping, the cooperative movement and rural medical systems.

We can see that Tagore’s educational philosophy was not merely bookish but also practical, not merely ideological but also pragmatic, not merely effective but also of quality, and not merely focused on the individual but also on uplifting the community. We can see that it was not pedantic but contextual, not blind but appropriate, and not profit-oriented but promoting human flourishing.

(To be concluded)

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoRemarkable turnaround for Sri Lanka’s ODI team

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoScammed and Stranded: The Dark Side of Sri Lanka’s Migration Industry

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUN Global Compact Network Sri Lanka: Empowering Businesses to Lead Sustainability in 2025 & Beyond

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSpeaker agrees to probe allegations of ‘unethical funding’ by USAID

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDon’t betray baiyas who voted you into power for lack of better alternative: a helpful warning to NPP – II

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoTwo films and comments

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoClean Sri Lanka and Noise Pollution (Part II)

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoCoal giant awakes, but uncertainty prevails