Midweek Review

Looking back at political assassinations, violence

During the JVP-led second abortive insurgency, its military wing killed quite a number of people, including politicians. Among the victims were Keerthi Abeywickrema, MP, and actor-turned-politician Vijaya Kumaratunga, killed in August 1987 and in February 1988, respectively. Vijaya Kumaratunga was shot dead outside his residence at Polhengoda. Abeywickrema was killed in a grenade attack on the UNP parliamentary group in committee room A. If the attacker had been successful in directing the attack on the UNP parliamentary group, as he desired, the results could have been catastrophic. Among those present therein were President J.R. Jayewardene, Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa and National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali. About 120 MPs had been present at the meeting, the first gathering of the group following the signing of the Indo-Lanka peace accord on July 29, 1987. Elections held during 1987-1990 were marred by violence with the JVP carrying out attacks on those who dared to vote.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

President Ranil Wickremesinghe expressed shock at the failed assassination bid on former US President Donald Trump, 78, during a campaign event at Butler, Pennsylvania.

Declaring that he was relieved to learn that Trump survived the July 13 attempt, Wickremesinghe said that Sri Lankans had been victims of such violence in politics. Trump was wounded in his right ear.

The ex-President’s would-be-assassin 20-year-old Thomas Matthew Crooks was shot dead by a Secret Service sniper 26 seconds after he fired the first of eight shots. Crooks used a semi-automatic AR rifle owned by many gun enthusiasts in a country obsessed with being gun owners as a right.

So far, the US media haven’t been able to at least speculate on Crooks motive. What really triggered a young man who had been living with his parents about an hour away from the scene to attempt to assassinate such a high profile target? Crooks appeared to have acted alone but the possibility of him being influenced by terrorism elsewhere cannot be ruled out. The young man could have been influenced even by US actions abroad over the years.

We are, however, not one bit surprised as the USA is the country where the so-called independent mainstream media helped to mislead its masses about the assassination of its 35th President John Fitzgerald Kennedy by its entrenched deep state to this day. And, according to his nephew Robert Kennedy Jr, who is an independent Presidential candidate now running for President, even his own father was assassinated by the deep state in 1968 as he campaigned to be President. In both instances apparent patsies were blamed for the dastardly crimes.

[In July, 2011 Norwegian far-right extremist Anders Behring Brevik killed 77 people, many of them teenagers, in a bomb attack and gun rampage. Breivik made references to the LTTE’s eviction of Muslims from the North in 1990 in his so-called ‘manifesto.’ There had been two references (i) Pro-Sri Lanka (supports the deportation of all Muslims from Sri Lanka) on page 1235 (ii) Fourth Generation War is normally characterised by a “stateless” entity fighting a state or regime. Fighting can be physically such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) to use a modern example (Page 1479)]

A person seated behind Trump died. Two more persons also received gunshot injuries.

One thing is clear. Regardless of the outcome of the attempt, Crooks, who had graduated from a high school two years ago, was definitely on a suicide mission. The young man couldn’t have expected, under any circumstances, to give the slip to Secret Service snipers positioned therein, once he opened fire.

Whatever his motive, Crooks had been absolutely ready to sacrifice his life to take out his target, Republican presidential candidate Trump. That is the truth the US appeared to have conveniently ignored. The bottom line is that Crooks would have ended up in a morgue whether he succeeded or failed in his attempt.

As President Wickremesinghe recalled, Sri Lankans had been victims of political violence. Subsequently, the President proposed enhanced security measures for candidates at the forthcoming presidential election, as well as former presidents.

Let me examine political assassinations during the northern and southern terrorism campaigns (the terrorist threat on the executive and legislature as well as lower level of political representation at Local Government and Provincial Councils level) before the successful conclusion of the anti-JVP campaign and war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) by January 1990 and May 2009, respectively.

In addition to the LTTE, the other Tamil terrorist groups carried out attacks. Of them, the TELO (currently represented in Parliament through the TNA) was definitely responsible for killing two Jaffna District ex-lawmakers V. Dharmalingam and M. Alalasundaram in early Sept. 1985. Dharmalingam’s son, Dharmalingham Siddharathan, MP, has accused the TELO of carrying out the twin assassinations at the behest of Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) of India.

India ended its military mission in late March 1990 (July 1987 to March 1990).

Two CFA-time assassinations

Kumaratunga lost her right eye as a result of the suicide blast at Town Hall, Colombo

During the war in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, snipers took many targets, almost all in those areas. There had been only one victim of a sniper outside the war-torn regions during that entire conflict. That was Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar assassinated at his No 36, Bullers Lane residence on the night of August 12, 2005. The other high profile victim had been de-facto leader of EPRLF Thambirajah Subathiran aka Robert.

Both assassinations, carried out during the Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) that had been spearheaded by Norway with the backing of the US, Japan and EU, underscored the vulnerability of the Sri Lankan State. By 2003, the EPRLF had been divided into two groups – one led by Arumugam Kandaiah Premachandran, better known as Suresh Premachandran, and Annamalai Varatharaja Perumal, the first and the only Chief Minister of the North East Provincial Council.

In the absence of Perumal, who resided in India under their protection, Robert led the EPRLF here. An LTTEer sniped Robert as he was doing physical exercises on top of the two storeyed EPELF party office on the Jaffna Hospital road. The sniper had fired from an unused classroom of a three-storeyed building in the southern area of Vembadi Girl’s High School.

The government conveniently failed to properly probe the Jaffna assassination. The LTTE obviously exploited lowering of overall security measures in the wake of the CFA signed on February 21, 2002, to assassinate the de facto EPRLF leader on the morning of June 14, 2003. By then the LTTE had quit the negotiating table and was increasingly acting in an extremely aggressive manner.

Then Major General Sarath Fonseka had been the Security Forces Commander, Jaffna (March 09, 2002 to Dec 15, 2003). That was his second stint at that particular position. Fonseka first served there from April 21, 2000 to August 3, 2000 during the Jaffna crisis.

The man who sniped Robert from a distance of about 200 metres, was never caught though he may have died subsequently during the conflict.

Hours after the assassination carried out at 6.15 am, the writer contacted the then Army Commander Lt. Gen. Lionel Balagalle, and military spokesman Brigadier Sanath Karunaratne, as well as EPRLF contacts at that time (Tiger sniper kills senior EPRLF politician, The Sunday Island, June 15, 2003).

The police, military and the EPRLF didn’t rule out the possibility of Vembadi Girl’s school authorities being aware of the assassination plot. Premier Ranil Wickremesinghe, at that time bending backwards to appease the LTTE regardless of consequences, and President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, failed to reach consensus on a tangible course of action to meet the terrorist threat.

The assassination of Kadirgamar, in Colombo, two months short of two years of signing the literally one sided ceasefire agreement, proved the assumption the group was ready to execute all-out war.

Kadirgamar was sniped around 10.30 p.m. as he stepped out of his swimming pool and went to look at his garden in the backyard, wearing slippers. The gunman fired at him from the window of a bathroom located on the top floor of house number 42, on Buller’s Lane, owned by Lakshman Thalayasingam, the son of a senior retired police officer. Thalayasingam told the police that he and his wife used only the ground floor of their house and that they weren’t aware of what was going on the top floor.

Later, it was revealed that those responsible for Kadirgamar’s security never subjected Thalayasingam’s residence on a directive of the Foreign Minister.

How Lankans perpetrated political violence abroad

No one else could have written about the assassination of former Indian Premier Rajiv Gandhi, as well as the President of the Congress Party (I), better than D.P. Kaarthikeyan and Radhavinod Raju, head of the Special Investigation Team of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBO) and key investigator, respectively.

Triumph of Truth: The Rajiv Gandhi Assassination – The Investigation first released in 2004 methodically dealt with the high profile overseas operation carried out by the LTTE. Gandhi, who was on the last leg of the parliamentary election campaign in 1991, when the LTTE struck at Sriperumbudur, a little village about 50 kms south-west of Chennai. At the time the LTTE mounted the attack, Gandhi had been under the protection of the Special Branch of the Tamil Nadu State Police. The authors explained the extremely poor security environment; those who had been assigned to guard Gandhi were compelled to work particularly due to lack of security equipment and Congress supporters responsible for causing chaos.

But what really impressed the reader regarding meticulous planning carried out by the LTTE, as revealed by former Indian investigators, was how the group tasked with the assassination conducted a ‘dry run’ for the Gandhi assassination.

The group had rehearsed at a political meeting addressed by V. P. Singh at Nandanam in Chennai on May 7, 1991. Rajiv Gandhi was killed on May 21, 1991. The girls, known as Subha and Dhanu, who had been assigned for Gandhi assassination, managed to get close enough to Singh to garland him. Singh took the garland from Dhanu at the last moment and the person (Nalini Sriharan – one of the six convicts in the Gandhi assassination case she was released by the Supreme Court of India in Nov 2022) tasked to photograph the operation failed in her effort.

As the LTTE rehearsed before the assassination of Gandhi in Sriperumbudur, Robert in Jaffna and Kadirgamar in Colombo were finished off by it using snipers. Crooks, too, was certain to have previously visited the Agr International Building from where he took aim at the former President. US authorities haven’t so far explained why Crooks, who had been detected over an hour before the incident with a rangefinder – an instrument used to measure the distance to a target – was not detained.

Some Republican Senators demanded the immediate resignation of Secret Service Director Kimberly Cheatle. Perusal of US media reports indicated that law enforcement personnel at the scene had been fully aware of the threat and one unarmed local officer saw Crooks on top of the Agr International Building aiming a weapon, moments before he opened fire.

Political killings in the 90s

A few minutes before a suicide bomber blew up

Ranasinghe Premadasa at Armour Street, Maradana

President Ranasinghe Premadasa was blasted on May Day, 1993 by an LTTE suicide cadre who had infiltrated the UNP leader’s inner security cordon two years before. That assassination, near the Armour Street Police Station, soon after the writer returned to The Island editorial from a five minutes walking distance away, increased the threat of terrorism to a new level.

There hadn’t been such an attack on a high-profile political target before here though the LTTE also killed Rajiv Gandhi in a suicide bomb blast. The LTTE infiltrated the President’s security contingent. This wouldn’t have been possible if not for the President’s valet, Mohideen’s weakness for women and liquor. The relationship with Mohideen and the LTTE cadre (Kulaweerasingham Weerakumar alias Babu) who had been tasked for the mission was so close he even had access to the President’s bedroom at his private residence, Sucharitha.

It was pertinent to mention that Premadasa was assassinated three years after the eruption of Eelam War II in June 1990. The President’s security had been weakened to such an extent, the killer could even have planted a bomb inside the President’s bedroom or cause an explosion in a SLAF helicopter carrying him to his estate.

The assassination took place at a time of great political upheaval against the backdrop of the assassination of one-time colleague and political rival Lalith Athulathmudali on April 23, 1993 at a political rally at Kirulapone. Having overcome a bid to impeach him in 1991 amidst catastrophic battlefield losses, President Premadasa seemed to have engaged in a process of consolidation when the LTTE removed him.

Like the Gandhi assassination, Premadasa’s killing altered Sri Lanka’s political direction.

The killing of State Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne in March 1992, UNP presidential candidate Gamini Dissanayake in Oct 1994 and the failed bid on President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s life in Dec 1999 underscored the overwhelming threat posed by the LTTE that received financial backing from the Tamil Diaspora based in the West.

Dissanayake was killed while campaigning for the 1994 presidential election whereas Kumaratunga survived the blast directed at her as she was campaigning for her second term. Had the LTTE succeeded, perhaps UNP candidate Ranil Wickremesinghe could have won the contest. The killing of Dissanayake helped Kumaratunga to win the 1994 election. The LTTE obviously worked in mysterious ways.

The global community turned a blind eye to LTTE efforts to destroy the political party system here, while outwardly singing hosannas for democratic values world over. The group targeted both the executive and legislature. Former Army Commander General C.S. Weerasooriya in his recently launched autobiography ‘Duty & Devotion’ dealt with how systematic elimination of key political party men undermined the country.

The LTTE killed quite a number of Tamil parliamentarians, including Appapillai Amirthalingam and Vettuvelu Yogeswaran. Like the assassination of Robert and Kadirgamar during the CFA arranged by Norway, the LTTE eliminated Amirthalingam and Yogeswaran as it was engaged in negotiations with President Premadasa (1989 May-June 1990).

Western powers reiterated their lenient attitude towards separatist terrorism here in the wake of Kadirgamar’s assassination. Instead of immediate retaliatory measures against the LTTE, they demanded Sri Lanka’s commitment to a much flawed peace process.

The US statement exposed the duplicity in their stand. The then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, in a statement issued on August 12, 2005 declared: “I am shocked and saddened by the assassination of Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar. This senseless murder was a vicious act of terror, which the United States strongly condemns. Those responsible must be brought to justice.

I offer my deepest sympathies and condolences to Mr. Kadirgamar’s family and to his friends and colleagues in Sri Lanka who will miss him greatly.

I last met Foreign Minister Kadirgamar this June. He was a man of dignity, honour and integrity, who devoted his life to bringing peace to Sri Lanka. Together, we must honour his memory by re-dedicating ourselves to peace and ensuring that the Cease-Fire remains in force.”

How could Sri Lanka bring those responsible for the Kadirgamar assassination to justice while ensuring that the highly flawed Norwegian arranged CFA remained in force?

In spite of on and off statements issued following high profile attacks, Western powers accepted violence perpetrated by the LTTE as part of their strategy.

Minister Douglas Devananda is one of the luckiest to escape LTTE operations to kill him. Of the many LTTE attempts, the deadliest was the bid made in late Nov 2007 to introduce a disabled woman with explosives hidden in her brassiere into Devananda’s office at Isipathana road, Narahenpita. Suspicious security staff thwarted her attempt. She triggered a blast killing several on the spot. Devananda, who was in his office, escaped.

Two other high profile assassinations were that of Minister Jeyaraj Fernandopulle in the Katana police area on April 6, 2008 and Puttalam District MP D.M. Dassanayake on January 08, 2008 at Ja-Ela.

The combined forces eradicated the LTTE less than two years later.

Over 15 years after the conclusion of the war, a lawmaker was killed in broad light at Nittambuwa by people influenced by Aragalaya. The Speaker himself claimed that he was also threatened by those behind Aragalaya. The ousted President, too, claimed the conspiracy also targeted him. There hadn’t been proper investigation to date as to what happened during the March 31-July 14, 2022 period that changed the course of Sri Lanka’s history. The common thread in all that was outgoing US Ambassador Julie Chung as she defended it as a peaceful protest movement and insisted that security forces and police should not lay a hand on them.

Midweek Review

Daya Pathirana killing and transformation of the JVP

JVP leader Somawansa Amarasinghe, who returned to Sri Lanka in late Nov, 2001, ending a 12-year self-imposed exile in Europe, declared that India helped him flee certain death as the government crushed his party’s second insurrection against the state in the ’80s, using even death squads. Amarasinghe, sole surviving member of the original politburo of the JVP, profusely thanked India and former Prime Minister V.P. Singh for helping him survive the crackdown. Neither the JVP nor India never explained the circumstances New Delhi facilitated Amarasinghe’s escape, particularly against the backdrop of the JVP’s frenzied anti-India campaign. The JVP has claimed to have killed Indian soldiers in the East during the 1987-1989 period. Addressing his first public meeting at Kalutara, a day after his arrival, Amarasinghe showed signs that the party had shed its anti-India policy of yesteryears. The JVPer paid tribute to the people of India, PM Singh and Indian officials who helped him escape.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

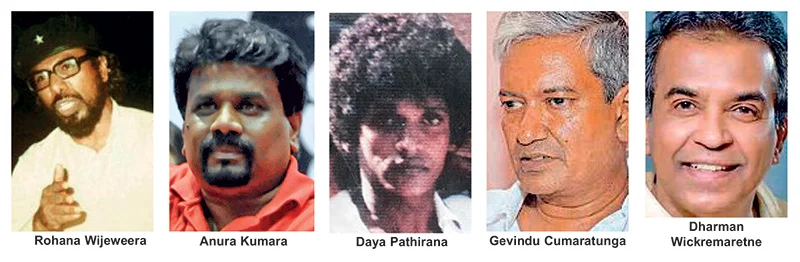

Forty years after the killing of Daya Pathirana, the third head of the Independent Student Union (ISU) by the Socialist Students’ Union (SSU), affiliated with the JVP, one-time Divaina journalist Dharman Wickremaretne has dealt with the ISU’s connections with some Tamil terrorist groups. The LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) hadn’t been among them, according to Wickremaretne’s Daya Pathirana Ghathanaye Nodutu Peththa (The Unseen Side of Daya Pathirana Killing), the fifth of a series of books that discussed the two abortive insurgencies launched by the JVP in 1971 and the early ’80s.

Pathirana was killed on 15 December, 1986. His body was found at Hirana, Panadura. Pathirana’s associate, Punchiralalage Somasiri, also of the ISU, who had been abducted, along with Pathirana, was brutally attacked but, almost by a miracle, survived to tell the tale. Daya Pathirana was the second person killed after the formation of the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya (DJV), the macabre wing of the JVP, in early March 1986. The DJV’s first head had been JVP politburo member Saman Piyasiri Fernando.

Its first victim was H. Jayawickrema, Principal of Middeniya Gonahena Vidyalaya, killed on 05 December, 1986. The JVP found fault with him for suspending several students for putting up JVP posters.

Wickremaretne, who had been relentlessly searching for information, regarding the violent student movements for two decades, was lucky to receive obviously unconditional support of those who were involved with the SSU and ISU as well as other outfits. Somasiri was among them.

Deepthi Lamaheva had been ISU’s first leader. Warnakulasooriya succeeded Lamahewa and was replaced by Pathirana. After Pathirana’s killing K.L. Dharmasiri took over. Interestingly, the author justified Daya Pathirana’s killing on the basis that those who believed in violence died by it.

Wickremaretne’s latest book, the fifth of the series on the JVP, discussed hitherto largely untouched subject – the links between undergraduates in the South and northern terrorists, even before the July 1983 violence in the wake of the LTTE killing 12 soldiers, and an officer, while on a routine patrol at Thinnavely, Jaffna.

The LTTE emerged as the main terrorist group, after the Jaffna killings, while other groups plotted to cause mayhem. The emergence of the LTTE compelled the then JRJ government to transfer all available police and military resources to the North, due to the constant attacks that gradually weakened government authority there. In Colombo, ISU and Tamil groups, including the PLOTE (People’s Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) enhanced cooperation. Wickremaretne shed light on a disturbing ISU-PLOTE connection that hadn’t ever been examined or discussed or received sufficient public attention.

In fact, EROS (Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students), too, had been involved with the ISU. According to the author, the ISU had its first meeting on 10 April, 1980. In the following year, ISU established contact with the EPRLF (Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front). The involvement of ISU with the PLOTE and Wickremaretne revealed how the SSU probed that link and went to the extent of secretly interrogating ISU members in a bid to ascertain the details of that connection. ISU activist Pradeep Udayakumara Thenuwara had been forcibly taken to Sri Jayewardenepura University where he was subjected to strenuous interrogation by SSU in a bid to identify those who were involved in a high profile PLOTE operation.

The author ascertained that the SSU suspected Pathirana’s direct involvement in the PLOTE attack on the Nikaweratiya Police Station, and the Nikaweratiya branch of the People’s Bank, on April 26, 1985. The SSU believed that out of a 16-member gang that carried out the twin attacks, two were ISU members, namely Pathirana, and another identified as Thalathu Oya Seneviratne, aka Captain Senevi.

The SSU received information regarding ISU’s direct involvement in the Nikaweratiya attacks from hardcore PLOTE cadre Nagalingam Manikkadasan, whose mother was a Sinhalese and closely related to JVP’s Upatissa Gamanayake. The LTTE killed Manikkadasan in a bomb attack on a PLOTE office, in Vavuniya, in September, 1999. The writer met Manikkadasan, at Bambapalitiya, in 1997, in the company of Dharmalingham Siddharthan. The PLOTE had been involved in operations in support of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s administration.

It was President Premadasa who first paved the way for Tamil groups to enter the political mainstream. In spite of some of his own advisors expressing concern over Premadasa’s handling of negotiations with the LTTE, he ordered the then Elections Commissioner Chandrananda de Silva to grant political recognition to the LTTE. The LTTE’s political wing PFLT (People’s Front of Liberation Tigers) received recognition in early December, 1989, seven months before Eelam War II erupted.

Transformation of ISU

The author discussed the formation of the ISU, its key members, links with Tamil groups, and the murderous role in the overall counter insurgency campaign during JRJ and Ranasinghe Premadasa presidencies. Some of those who had been involved with the ISU may have ended up with various other groups, even civil society groups. Somasiri, who was abducted along with Pathirana at Thunmulla and attacked with the same specialised knife, but survived, is such a person.

Somasiri contested the 06 May Local Government elections, on the Jana Aragala Sandhanaya ticket. Jana Aragala Sandhanaya is a front organisation of the Frontline Socialist Party/ Peratugaami pakshaya, a breakaway faction of the JVP that also played a critical role in the violent protest campaign Aragalaya against President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. That break-up happened in April 2012, The wartime Defence Secretary, who secured the presidency at the 2019 presidential election, with 6.9 mn votes, was forced to give up office, in July 2022, and flee the country.

Somasiri and Jana Aragala Sandhanaya were unsuccessful; the group contested 154 Local Government bodies and only managed to secure only 16 seats whereas the ruling party JVP comfortably won the vast majority of Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas.

Let us get back to the period of terror when the ISU was an integral part of the UNP’s bloody response to the JVP challenge. The signing of the Indo-Lanka accord, in late July 1987, resulted in the intensification of violence by both parties. Wickremaretne disclosed secret talks between ISU leader K.L. Dharmasiri and the then Senior SSP (Colombo South) Abdul Cader Abdul Gafoor to plan a major operation to apprehend undergraduates likely to lead protests against the Indo-Lanka accord. Among those arrested were Gevindu Cumaratunga and Anupa Pasqual. Cumaratunga, in his capacity as the leader of civil society group Yuthukama, that contributed to the campaign against Yahapalanaya, was accommodated on the SLPP National List (2020 to 2024) whereas Pasqual, also of Yuthukama, entered Parliament on the SLPP ticket, having contested Kalutara. Pasqual switched his allegiance to Ranil Wickremesinghe after Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s ouster in July 2022.

SSU/JVP killed K.L. Dharmasiri on 19 August, 1989, in Colomba Kochchikade just a few months before the Army apprehended and killed JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera. Towards the end of the counter insurgency campaign, a section of the ISU was integrated with the military (National Guard). The UNP government had no qualms in granting them a monthly payment.

Referring to torture chambers operated at the Law Faculty of the Colombo University and Yataro operations centre, Havelock Town, author Wickremaretne underscored the direct involvement of the ISU in running them.

Maj. Tuan Nizam Muthaliff, who had been in charge of the Yataro ‘facility,’ located near State Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne’s residence, is widely believed to have shot Wijeweera in November, 1989. Muthaliff earned the wrath of the LTTE for his ‘work’ and was shot dead on May 3, 2005, at Polhengoda junction, Narahenpita. At the time of Muthaliff’s assassination, he served in the Military Intelligence.

Premadasa-SSU/JVP link

Ex-lawmaker and Jathika Chinthanaya Kandayama stalwart Gevindu Cumaratunga, in his brief address to the gathering, at Wickremaretne’s book launch, in Colombo, compared Daya Pathirana’s killing with the recent death of Nandana Gunatilleke, one-time frontline JVPer.

Questioning the suspicious circumstances surrounding Gunatilleke’s demise, Cumaratunga strongly emphasised that assassinations shouldn’t be used as a political tool or a weapon to achieve objectives. The outspoken political activist discussed the Pathirana killing and Gunatilleke’s demise, recalling the false accusations directed at the then UNPer Gamini Lokuge regarding the high profile 1986 hit.

Cumaratunga alleged that the SSU/JVP having killed Daya Pathirana made a despicable bid to pass the blame to others. Turning towards the author, Cumaratunga heaped praise on Wickremaretne for naming the SSU/JVP hit team and for the print media coverage provided to the student movements, particularly those based at the Colombo University.

Cumaratunga didn’t hold back. He tore into SSU/JVP while questioning their current strategies. At one point a section of the audience interrupted Cumaratunga as he made references to JVP-led Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB) and JJB strategist Prof. Nirmal Dewasiri, who had been with the SSU during those dark days. Cumaratunga recalled him attending Daya Pathirana’s funeral in Matara though he felt that they could be targeted.

Perhaps the most controversial and contentious issue raised by Cumaratunga was Ranasinghe Premadasa’s alleged links with the SSU/JVP. The ex-lawmaker reminded the SSU/JVP continuing with anti-JRJ campaign even after the UNP named Ranasinghe Premadasa as their candidature for the December 1988 presidential election. His inference was clear. By the time Premadasa secured the presidential nomination he had already reached a consensus with the SSU/JVP as he feared JRJ would double cross him and give the nomination to one of his other favourites, like Gamini Dissanayake or Lalith Athulathmudali.

There had been intense discussions involving various factions, especially among the most powerful SSU cadre that led to putting up posters targeting Premadasa at the Colombo University. Premadasa had expressed surprise at the appearance of such posters amidst his high profile ‘Me Kawuda’ ‘Monawada Karanne’poster campaign. Having questioned the appearance of posters against him at the Colombo University, Premadasa told Parliament he would inquire into such claims and respond. Cumaratunga alleged that night UNP goons entered the Colombo University to clean up the place.

The speaker suggested that the SSU/JVP backed Premadasa’s presidential bid and the UNP leader may have failed to emerge victorious without their support. He seemed quite confident of his assertion. Did the SSU/JVP contribute to Premadasa’s victory at one of the bloodiest post-independence elections in our history.

Cumaratunga didn’t forget to comment on his erstwhile comrade Anupa Pasqual. Alleging that Pasqual betrayed Yuthukama when he switched allegiance to Wickremesinghe, Cumaratunga, however, paid a glowing tribute to him for being a courageous responder, as a student leader.

SSU accepts Eelam

One of the most interesting chapters was the one that dealt with the Viplawadi Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna/Revolutionary Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (RJVP), widely known as the Vikalpa Kandaya/Alternative Group and the ISU mount joint campaigns with Tamil groups. Both University groups received weapons training, courtesy PLOTE and EPRLF, both here, and in India, in the run-up to the so-called Indo-Lanka Peace Accord. In short, they accepted Tamils’ right to self-determination.

The author also claimed that the late Dharmeratnam Sivaram had been in touch with ISU and was directly involved in arranging weapons training for ISU. No less a person than PLOTE Chief Uma Maheswaran had told the author that PLOTE provided weapons training to ISU, free of charge ,and the JVP for a fee. Sivaram, later contributed to several English newspapers, under the pen name Taraki, beginning with The Island. By then, he propagated the LTTE line that the war couldn’t be brought to a successful conclusion through military means. Taraki was abducted near the Bambalapitiya Police Station on the night of 28 April, 2005, and his body was found the following day.

The LTTE conferred the “Maamanithar” title upon the journalist, the highest civilian honour of the movement.

In the run up to the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord, India freely distributed weapons to Tamil terrorist groups here who in turn trained Sinhala youth.

Had it been part of the overall Indian destabilisation project, directed at Sri Lanka? PLOTE and EPRLF couldn’t have arranged weapons training in India as well as terrorist camps here without India’s knowledge. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka never sought to examine the origins of terrorism here and identified those who propagated and promoted separatist ideals.

Exactly a year before Daya Pathirana’s killing, arrangements had been made by ISU to dispatch a 15-member group to India. But, that move had been cancelled after law enforcement authorities apprehended some of those who received weapons training in India earlier. Wickremaretne’s narrative of the students’ movement, with the primary focus of the University of Colombo, is a must read. The author shed light on the despicable Indian destabilisation project that, if succeeded, could have caused and equally destructive war in the South. In a way, Daya Pathirana’s killing preempted possible wider conflict in the South.

Gevindu Cumaratunga, in his thought-provoking speech, commented on Daya Pathirana. At the time Cumaratunga entered Colombo University, he hadn’t been interested at all in politics. But, the way the ISU strongman promoted separatism, influenced Cumaratunga to counter those arguments. The ex-MP recollected how Daya Pathirana, a heavy smoker (almost always with a cigarette in his hand) warned of dire consequences if he persisted with his counter views.

In fact, Gevindu Cumaratunga ensured that the ’80s terror period was appropriately discussed at the book launch. Unfortunately, Wickremaretne’s book didn’t cause the anticipated response, and a dialogue involving various interested parties. It would be pertinent to mention that at the time the SSU/JVP decided to eliminate Daya Pathirana, it automatically received the tacit support of other student factions, affiliated to other political parties, including the UNP.

Soon after Anura Kumara Dissanayake received the leadership of the JVP from Somawansa Amarasinghe, in December 2014, he, in an interview with Saroj Pathirana of BBC Sandeshaya, regretted their actions during the second insurgency. Responding to Pathirana’s query, Dissanayake not only regretted but asked for forgiveness for nearly 6,000 killings perpetrated by the party during that period. Author Wickremaretne cleverly used FSP leader Kumar Gunaratnam’s interview with Upul Shantha Sannasgala, aired on Rupavahini on 21 November, 2019, to remind the reader that he, too, had been with the JVP at the time the decision was taken to eliminate Daya Pathirana. Gunaratnam moved out of the JVP, in April 2012, after years of turmoil. It would be pertinent to mention that Wimal Weerawansa-Nandana Gunatilleke led a group that sided with President Mahinda Rajapaksa during his first term, too, and had been with the party by that time. Although the party split over the years, those who served the interests of the JVP, during the 1980-1990 period, cannot absolve themselves of the violence perpetrated by the party. This should apply to the JVPers now in the Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB), a political party formed in July 2019 to create a platform for Dissanayake to contest the 2019 presidential election. Dissanayake secured a distant third place (418,553 votes [3.16%])

However, the JVP terrorism cannot be examined without taking into JRJ’s overall political strategy meant to suppress political opposition. The utterly disgusting strategy led to the rigged December 1982 referendum that gave JRJ the opportunity to postpone the parliamentary elections, scheduled for August 1983. JRJ feared his party would lose the super majority in Parliament, hence the irresponsible violence marred referendum, the only referendum ever held here to put off the election. On 30 July, 1983, JRJ proscribed the JVP, along with the Nawa Sama Samaja Party and the Communist Party, on the false pretext of carrying out attacks on the Tamil community, following the killing of 13 soldiers in Jaffna.

Under Dissanayake’s leadership, the JVP underwent total a overhaul but it was Somawansa Amarasinghe who paved the way. Under Somawansa’s leadership, the party took the most controversial decision to throw its weight behind warwinning Army Chief General (retd) Sarath Fonseka at the 2010 presidential election. That decision, the writer feels, can be compared only with the decision to launch its second terror campaign in response to JRJ’s political strategy. How could we forget Somawansa Amarasinghe joining hands with the UNP and one-time LTTE ally, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), to field Fonseka? Although they failed in that US-backed vile scheme, in 2010, success was achieved at the 2015 presidential election when Maithripala Sirisena was elected.

Perhaps, the JVP took advantage of the developing situation (post-Indo-Lanka Peace Accord), particularly the induction of the Indian Army here, in July 1987, to intensify their campaign. In the aftermath of that, the JVP attacked the UNP parliamentary group with hand grenades in Parliament. The August 1987 attack killed Matara District MP Keerthi Abeywickrema and staffer Nobert Senadheera while 16 received injuries. Both President JRJ and Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa had been present at the time the two hand grenades were thrown at the group.

Had the JVP plot to assassinate JRJ and Premadasa succeeded in August 1987, what would have happened? Gevindu Cumaratunga, during his speech also raised a very interesting question. The nationalist asked where ISU Daya Pathirana would have been if he survived the murderous JVP.

Midweek Review

Reaping a late harvest Musings of an Old Man

I am an old man, having reached “four score and five” years, to describe my age in archaic terms. From a biological perspective, I have “grown old.” However, I believe that for those with sufficient inner resources, old age provides fertile ground to cultivate a new outlook and reap a late harvest before the sun sets on life.

Negative Characterisation of Old Age

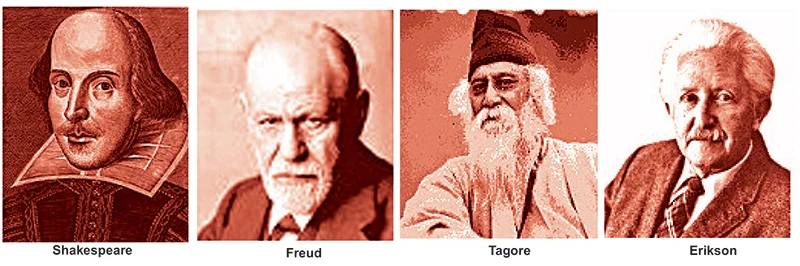

My early medical education and training familiarised me with the concept of biological ageing: that every living organism inevitably undergoes progressive degeneration of its tissues over time. Old age is often associated with disease, disability, cognitive decline, and dependence. There is an inkling of futility, alienation, and despair as one approaches death. Losses accumulate. As Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, “When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.” Doctors may experience difficulty in treating older people and sometimes adopt an attitude of therapeutic nihilism toward a life perceived to be in decline.

Categorical assignment of symptoms is essential in medical practice when arriving at a diagnosis. However, placing an individual into the box of a “geriatric” is another matter, often resulting in unintended age segregation and stigmatisation rather than liberation of the elderly. Such labelling may amount to ageism. It is interesting to note that etymologically, the English word geriatric and the Sanskrit word jara both stem from the Indo-European root geront, meaning old age and decay, leading to death (jara-marana).

Even Sigmund Freud (1875–1961), the doyen of psychoanalysis, who influenced my understanding of personality structure and development during my psychiatric training, focused primarily on early development and youth, giving comparatively little attention to the psychology of old age. He believed that instinctual drives lost their impetus with ageing and famously remarked that “ageing is the castration of youth,” implying infertility not only in the biological sense. It is perhaps not surprising that Freud began his career as a neurologist and studied cerebral palsy.

Potential for Growth in Old Age

The model of human development proposed by the psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1994), which he termed the “eight stages of man,” is far more appealing to me. His theory spans the entire life cycle, with each stage presenting a developmental task involving the negotiation of opposing forces; success or failure influences the trajectory of later life. The task of old age is to reconcile the polarity between “ego integrity” and “ego despair,” determining the emotional life of the elderly.

Ego integrity, according to Erikson, is the sense of self developed through working through the crises (challenges) of earlier stages and accruing psychological assets through lived experience. Ego despair, in contrast, results from the cumulative impact of multiple physical and emotional losses, especially during the final stage of life. A major task of old age is to maintain dignity amidst such emotionally debilitating forces. Negotiating between these polarities offers the potential for continued growth in old age, leading to what might be called a “meaningful finish.”

I do not dispute the concept of biological ageing. However, I do not regard old age as a terminal phase in which growth ceases and one is simply destined to wither and die. Though shadowed by physical frailty, diminishing sensory capacities and an apparent waning of vitality, there persists a proactive human spirit that endures well into late life. There is a need in old age to rekindle that spirit. Ageing itself can provide creative opportunities and avenues for productivity. The aim is to bring life to a meaningful close.

To generate such change despite the obstacles of ageing — disability and stigmatisation — the elderly require a sense of agency, a gleam of hope, and a sustaining aspiration. This may sound illusory; yet if such illusions are benign and life-affirming, why not allow them?

Sharon Kaufman, in her book The Ageless Self: Sources of Meaning in Late Life, argues that “old age” is a social construct resisted by many elders. Rather than identifying with decline, they perceive identity as a lifelong process despite physical and social change. They find meaning in remaining authentically themselves, assimilating and reformulating diverse life experiences through family relationships, professional achievements, and personal values.

Creative Living in Old Age

We can think of many artists, writers, and thinkers who produced their most iconic, mature, or ground-breaking work in later years, demonstrating that creativity can deepen and flourish with age. I do not suggest that we should all aspire to become a Monet, Picasso, or Chomsky. Rather, I use the term “creativity” in a broader sense — to illuminate its relevance to ordinary, everyday living.

Endowed with wisdom accumulated through life’s experiences, the elderly have the opportunity for developmental self-transformation — to connect with new identities, perspectives, and aspirations, and to engage in a continuing quest for purpose and meaning. Such a quest serves an essential function in sustaining mental health and well-being.

Old age offers opportunities for psychological adaptation and renewal. Many elders use the additional time afforded by retirement to broaden their knowledge, pursue new goals, and cultivate creativity — an old age characterised by wholeness, purpose, and coherence that keeps the human spirit alive and growing even as one’s days draw to a close.

Creative living in old age requires remaining physically, cognitively, emotionally, and socially engaged, and experiencing life as meaningful. It is important to sustain an optimistic perception of health, while distancing oneself from excessive preoccupation with pain and trauma. Positive perceptions of oneself and of the future help sustain well-being. Engage in lifelong learning, maintain curiosity, challenge assumptions — for learning itself is a meaning-making process. Nurture meaningful relationships to avoid disengagement, and enter into respectful dialogue, not only with those who agree with you. Cultivate a spiritual orientation and come to terms with mortality.

The developmental task of old age is to continue growing even as one approaches death — to reap a late harvest. As Rabindranath Tagore expressed evocatively in Gitanjali [‘Song Offerings’], which won him the Nobel Prize:: “On the day when death will knock at thy door, what wilt thou offer to him?

Oh, I will set before my guest the full vessel of my life — I will never let him go with empty hands.”

by Dr Siri Galhenage

Psychiatrist (Retired)

[sirigalhenage@gmail.com]

Midweek Review

Left’s Voice of Ethnic Peace

Multi-gifted Prof. Tissa Vitarana in passing,

Leaves a glowing gem of a memory comforting,

Of him putting his best foot forward in public,

Alongside fellow peace-makers in the nineties,

In the name of a just peace in bloodied Sri Lanka,

Caring not for personal gain, barbs or brickbats,

And for such humanity he’ll be remembered….

Verily a standard bearer of value-based politics.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Life style7 days ago

Life style7 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGiants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world