Features

Japanese Digital Television Project: An informed choice?

by Shanthilal Nanayakkara

Retired Principal Engineer, Digital Transition Division, Australian Communications and Media Authority

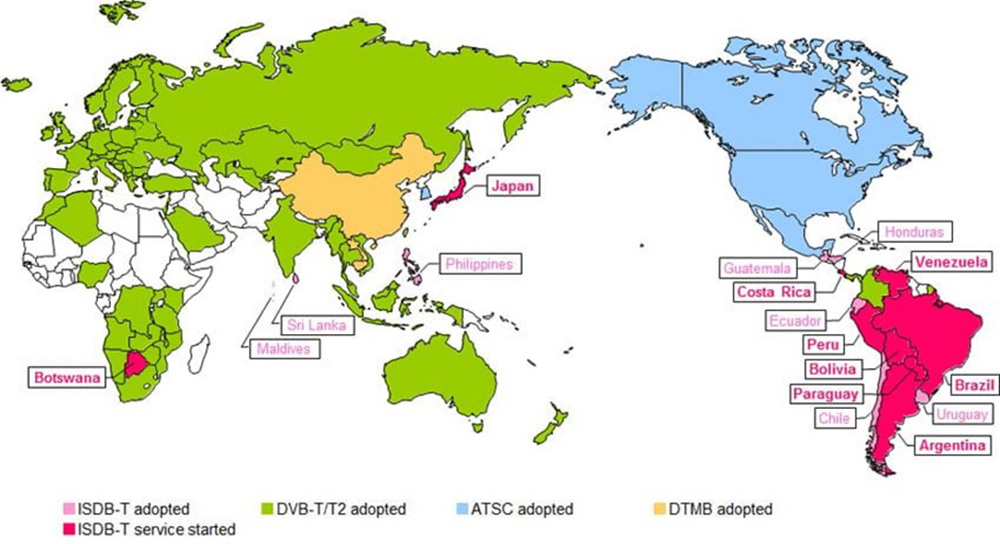

A Japanese delegation recently announced the resumption of the previously stalled digital television project in Sri Lanka following a meeting with the newly-elected President Anura Kumara Dissanayake. The commencement of the digitisation project is now imminent.

Once terrestrial television transmissions are digitised in Sri Lanka, it will replace the old analogue terrestrial television forever. Therefore, it is critically important that the final outcome is better than the current analogue television, if not far superior. Setting such a goal prior to the implementation of the project is crucial for its fruitful completion.

To achieve this outcome, deficiencies in the current parameters in the Japanese Digital Plans need to be revisited and appropriately addressed for the benefit of all stakeholders. Otherwise, as it stands today, there is a high potential for rural and regional viewers in Sri Lanka to miss out on the digital coverage. (This is further illustrated below). Such an unwarranted outcome could become a highly ‘politically sensitive’ issue for the new government .

Why Digital

In analogue transmissions, radio waves encounter several problems. When radio waves are subjected to multipath, ghosting images appear on television screen. They are also subjected to cancellation of their own signals and interference.

Digital technology overcomes these analogue transmission weaknesses and, as a huge value addition, is able to carry more information than its analogue counterpart. As this capacity enhancement feature helps carry multiple programmes on one frequency or channel, digital television transmission technology is considered to be highly spectrum productive. Once analogue is switched off, the vacant spectrum that can be harnessed, commonly known as Digital Dividend (DD), becomes an income earner for the Government, as spare spectrum can be sold to Telcos for broadband internet use. Thus, this digitisation project is effectively a self-financing venture for the government and a win-win for all stakeholders.

Stakeholder benefits of digital

Many countries in the world have now moved or are in the process of moving to the digital domain.

Irrespective of the digital television transmission standard adopted in Sri Lanka, benefits of a conversion from analogue to digital television are many for the majority of stakeholders.

These are listed below against the various stakeholders:

* Government – a significant income from selling the vacant spare spectrum to Telcos, following full conversion to digital, provided appropriate modifications are made to the JICA plan;

* Broadcasters – increased television channels and scope for increase of advertising revenue;

* Viewers – increased number of television channels to facilitate a wider selection of content, with True High Definition (True HD) quality and potential 5.1 Surround Sound;

* Content providers – opportunity to produce a wide range of programmes that are in demand;

* Production houses – larger revenue from vastly increased niche productions;

* Creators of social media and other internet-based content – opportunities to develop novel visual and aural media content;

* Electronic Manufacturing/Testing – opportunities to manufacture digital television receivers and set up a receiver harmonisation/compatibility centre;

* Broadcast Towers (similar to Lotus Tower) – Opportunities to establish and operate consolidated broadcast towers in the country;

* Telcos- opportunity to purchase superior vacant spectrum for future fixed and mobile broadband applications.

Funding arrangements or self-financing

The current funding arrangement for digitisation of television in Sri Lanka is a ‘soft loan’ from the Japanese government, and it is tied up in ‘one bundle’ with loans for other projects. This loan is also based on the premise that the deployment of the Japanese digital television standard, Integrated Services Digital Broadcasting-Terrestrial (ISDB-T) is mandatory. As the vacant spectrum can be sold after Analogue Switch Off (ASO), the venture could also be a self-financing project, albeit with bridging finance.

Purpose of this essay

The main purpose of this article is to suggest ways of optimising the benefits of the digitisation project while retaining the support of the Japanese government. If the bulk of problems for viewers and broadcasters can be removed by making appropriate adjustments to the current plans at a minimal cost, with broadcasters becoming willing participants, the digitisation of television in Sri Lanka would no doubt be a success for all stakeholders, including the new government. Otherwise, there is an urgent need to review the bi-lateral agreement that was signed previously.

The broadcasting fraternity in Sri Lanka is fully aware that the Japanese system is not as efficient as the second generation European standard, Digital Video Broadcast-Terrestrial 2 (DVB-T2).

Understanding Digital

Simply put, digitisation of analogue vision and sound enables radio waves to carry more information within the same channel or bandwidth than in the analogue era. This allows producers of visual and aural content to be more creative than before. The technology also facilitates easy communication in both fixed and mobile environments and facilitates two-way communication more than in the analogue era. However, there are two main pitfalls that one needs to address in order to make the venture a success. They are as follows:

Cliff effect (sudden loss of signal): –

* to avoid the ‘cliff effect’ a robust signal (with higher reliability and availability at a receive location than in analogue era) is needed at the receiver to prevent momentary picture pixelation and/or sudden loss of signal; and

* it is also necessary to ensure that all television digital services reaching viewer locations are of the same signal strength to ensure equity of services and therefore must originate from ONE location such as the Lotus Tower.

* Absence of ‘graceful degradation’ and its effect on signal level – even with a degraded signal with ‘snowy pictures’, analogue signal is still watchable. It is not so with digital due to ‘cliff effect’. Therefore, there is a need to ensure that the digital coverage is the same or better than the existing watchable analogue coverage that is defined by a signal level of 43 dBuV/m in VHF Band III.

This limit was adopted for digitisation in Australia.

Deficiencies of the Japanese standard/plan

In planning to deploy the ISDB-T system in our country, everyone should aim for a cost-beneficial outcome as it is of paramount importance to all stakeholders. There are several issues in the Japanese documentation of 2014/2018, which should be addressed to suit the needs of the public/consumers, broadcasters and government. They range from policy issues at the outset, technical areas during planning and management issues during the proposed phases of ASO and Digital Switch On (DSO).

Spectrum for Digital: VHF/UHF issue

In particular, the proposal to use only a part of the available broadcast spectrum has an impact on the eventual DD income for the Government. The Japanese have deployed both VHF and UHF spectrum in Brazil, strangely not offered to Sri Lanka. In that context, it is not clear why the Japanese team has not proposed a VHF and UHF combined solution as deployed in Brazil. This was pointed out by the writer when a Japanese team, including a senior Embassy official Sato Takefumi, met him in 2017 in Colombo to discuss Lotus Tower issues (after his disclosure in an article in The Island about the Lotus tower) and digitisation in general. Their response was ‘no one asked for it’.

As it stands today in Sri Lanka, analogue television transmissions are based on frequencies using both VHF and UHF Bands, but the proposed Japanese digital conversion is not utilising the VHF Band. In particular, VHF Band III exhibits superior propagation characteristics, while contributing to lower the consumption of electricity by the transmitters. More importantly, VHF radio waves carry longer distances than UHF due to lower propagation losses, are able to travel around obstacles comparatively and therefore VHF is more suitable for wide coverage transmissions.

Currently, the VHF spectrum is occupied by three television broadcasting networks i.e. Rupavahini, ITN and TNL. These networks will lose their inherent wide coverage VHF Band advantage. They also have the additional burden of occupying a digital channel in the UHF spectrum, especially when the earmarked UHF channels for digital are almost at the bottom of the UHF Band V, where propagation losses are higher than in UHF Band IV.

ISDB-T New Coder H.265

It is a known fact that the Japanese ISDB-T standard, in payload capacity terms, is second to the second generation European Standard DVB-T2 that provides 45 Mb/s capacity. However, the Japanese standard can only carry about 1/2 of the European standard per channel at 23 Mb/s. But as the Japanese are now offering to change the content source coder to H.265, they will be able to provide HD at 1080P at a rate of 2-4 Mb/s. This change would now allow all HD TV ready broadcasters to provide True HD content at 1920 x 1080P and possibly can accommodate all television channels in Colombo. But the downside is that the receivers are going to be more complex with the new coder. This may then lead to more expensive ISDB-T receivers or STBs in Sri Lanka.

Vacant VHF Band III

The unused VHF Band III is likely to reduce the DD for the government though the Japanese strategy is to achieve some productivity by the use of single frequency networks in the UHF Band (SFNs-a technique to use the same frequency multiple times to improve spectrum productivity). However, in practice receiving of SFNs is not simplistic as the reception of SFN signals are subject to receiver complexities.

The Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (TRC) may be exclusively reserving the VHF band for future digital radio, but the same band could be co-shared with digital television without any problems. For example, Australia is co-sharing VHF Band III for both digital television and radio without any issues.

Once all analogue transmissions are switched off with the deployment of UHF band per se for digital, the unused VHF Band III spectrum, where 7 MHz bandwidth, 8 VHF Frequency channels exists, will become vacant.

This is clearly a waste of unused spectrum. Additionally, as Restacking [restack is the re-arrangement of frequencies ideally in the two bands of VHF and UHF, to maximise the spectrum productivity] is in the Japanese Plan, additional expenditure on broadcasting infrastructure is also on the cards. Where are the funds coming from?

There is no mention of new funding arrangements for Restacking of the spectrum, and it also raises questions about the STB/Receiver specifications as frequencies may need to change after Restacking.

If some broadcasters are not keen to use ISDB-T, they may canvass for the opportunity to use the vacant VHF Band for the potential deployment of DVB-T2 standard. This MUST be avoided at all costs! If this happens, there will be two digital systems in Sri Lanka. This issue, in particular, could become another potential headache for the government as it is likely to be under heavy pressure from commercial broadcasters to release the vacant VHF Band III for the more efficient DVB-T2. This issue, too, was pointed out by the writer when another Japanese team consisting of a Senior Engineer from Yacheo Engineering along with Sato Takefumi of the Japanese Embassy met him in 2017/2018.

Unless there are plans to use the vacant VHF Band III by Restacking the spectrum, this spectrum specifically allocated for broadcasting would go to waste.

Digital Signal Reliability & Availability

Unlike in the analogue domain, television signal reliability and its availability becomes crucial in digital reception. In the analogue era, television broadcasting service field strength was planned for 50% of the locations and 50% of the time at a receiving height of 10 m. But in digital this becomes 80%-95% of the locations and 90% of the time to ensure reliability and availability of the digital signal. Hence the planned field strength would need to be adjusted to ensure the required reliability and availability at a higher field strength. In Australia, field strength used was 50 dBuV/m for Band IV and 54 dBuV/m for Band V frequencies in a rural environment

However, it is not clear from the published documents of the Japanese plans 2014/2018 whether this issue had been addressed or otherwise. The signal level at 51 dBuV/m identified in the 2018 Japanese documentation is certainly not adequate for a rural grade of service in the UHF Band! It ought to be in the region of 54-74 dBuV/m in the UHF Band V. For example, the Australian Broadcasting Planning Handbook for Digital Television Broadcasting has clearly identified these requirements and provided information on how they were derived.

Duplication Parameter

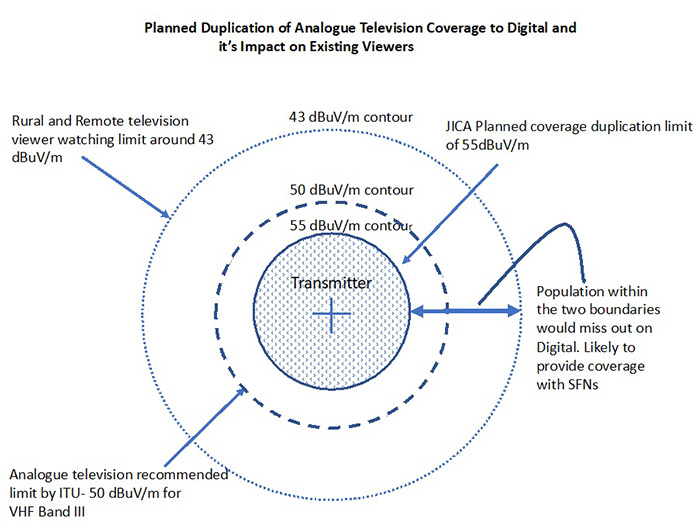

The potential impact of the proposals for duplication of coverage is illustrated in the diagram. (See Figure 01)

The signal threshold of a planned analogue coverage is 50 dBuV/m for VHF Band III. However, some regional and rural viewers in Sri Lanka are currently receiving watchable analogue signals well below this value. If, as planned by the Japanese studies in 2014, the analogue coverage is converted at the planned cut-off level of 55 dBuV/m, then the majority of regional and rural viewers, who are currently watching the analogue television with no issues, will not be able to receive digital television coverage. This could potentially become a political nightmare for the new government. Therefore, the cut-off signal level, as illustrated above, should be lowered to 43 dBuV/m.

Though Single Frequency Networks (SFNs) are a solution to mitigate this difference in coverage, it is not easy to implement them at the receiver-end due to the variation in receiver profiles of Set-Top-Boxes (STBs) and complexities in receiver SFN signal detection.

The Japanese designers, while being aware of this issue, may have been heavily constrained due to the requirement for spectrum productivity. Most probably, given the limits of the available UHF spectrum for digital and the lower data efficacy of the Japanese ISDB-T standard, this higher limit of duplication may have been proposed by the designers in order to preserve some spectrum productivity.

One Network Operator for Digital

The advent of digital terrestrial television also signifies the end of individual transmission facilities for broadcasters, as several content feeds are carried on one frequency or the channel and the requirement to consolidate all transmissions at one site. A combined digital transmission service provider may, in the future, be an independent entity and the facilities may be offered to the broadcasters on a fee-levying basis, based on a pragmatic business plan. In a future digital broadcasting landscape, the broadcasters will essentially be ‘content’ providers. Perhaps, there ought to be some sort of protection provided to the existing broadcasters in the event new content providers also express a desire to use digital transmissions.

Cost to viewers and broadcasters

All consumer television sets require digital receivers to extract video and audio content from digital transmissions. Therefore, either in-built ISDB-T receivers or compatible STBs are required. For example, there are flat TVs that do not have in-built ISDB-T receivers. The cost of an STB for ISDB-T with H.265 decoders, is likely to be around US $ 50-100, depending on their complexity and economies of scale. If in the event, there is likely to be a Restack of frequencies including the VHF Band, two band STBs or receivers may be needed; one during the first phase and another after the Restack of channels with the ability to tune into the VHF Band. Additionally, at some household locations, there may also be a requirement for new receiver antenna installation to receive VHF/UHF channels. If so, this is also an additional cost to the viewer.

There is also a significant cost to the commercial television broadcasters to provide HD ready studios, Outside Broadcast (OB)/Electronic News Gathering (ENG) equipment, and content feeding arrangements. However, once the commercial television broadcasters elect to use consolidated broadcast towers, analogue era transmission costs would also disappear as their independent transmission networks are no longer needed, in a digital environment. It is noteworthy to highlight that the Japanese financial proposal for digitisation of television is primarily for Rupavahini, and limited to funding the analogue to digital transfer of Rupavahini facilities, including the provision of a True HD studio, OB unit, Transmission equipment and a Central Command centre for the proposed Digital Broadcast Network Operations (DBNO) at the Lotus Tower.

At this stage, there are no signs of any discussions with the broadcasters to develop a ‘road map’ to facilitate the smooth transition from analogue to digital of commercial channels. If Restack is to take place, there is likely to be additional costs but there is no mention of further Japanese funding for Restack of channels either.

As additional costs to the commercial television broadcasters are likely, strategic government policy initiatives to compensate for the additional capital expenditure in a highly competitive market are in order.

Way forward

It is heartening to note that the Japanese plan has now incorporated the more efficient coder in H.265 with an intention to maximise the use of limited payload capacity of an ISDB-T channel, which then will result in providing True HD transmission (1920 x 1080P) for ALL licensed television channels in Colombo.

If Japanese consultants can pay attention to the issues of using VHF Band III, changing receiving the field strength requirements to that of the ITU signal level requirements for UHF and address the duplication parameter issue, then ALL stakeholders including the government and broadcasters will no doubt look forward to the venture of digitisation of television in Sri Lanka.

Features

Wishes, Resolutions and Climate Change

Exchanging greetings and resolving to do something positive in the coming year certainly create an uplifting atmosphere. Unfortunately, their effects wear off within the first couple of weeks, and most of the resolutions are forgotten for good. However, this time around, we must be different, because the nation is coming out of the most devastating natural disaster ever faced, the results of which will impact everyone for many years to come. Let us wish that we as a nation will have the courage and wisdom to resolve to do the right things that will make a difference in our lives now and prepare for the future. The truth is that future is going to be challenging for tropical islands like ours.

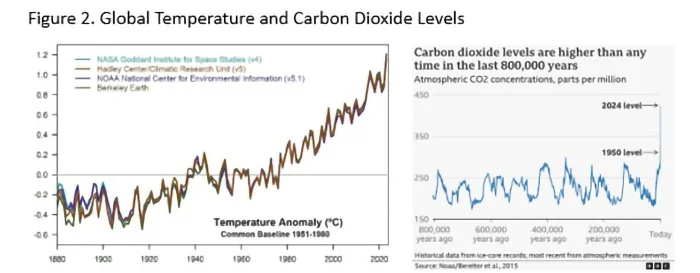

We must not have any doubts about global warming phenomenon and its impact on local weather patterns. Over its 4.5-billion-year history, the earth has experienced drastic climate changes, but it has settled into a somewhat moderate condition characterised by periods of glaciation and retreat over the last million years. Note that anatomically modern Homo sapiens have been around only for two to three hundred thousand years, and it is reasoned that this stable climate may have helped their civilisation. There have been five glaciation periods over the last five hundred thousand years, and these roughly hundred-thousand-year cycles are explained by the astronomical phenomenon known as the Milankovitch Cycle (the lows marked with stars in Figure 1). At present, the earth is in an inter glacial period and the next glaciation period will be in about eighty thousand years.

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

During these cycles, the global mean temperature has changed by about 7-8 degrees Centigrade. In contrast to this natural variation, earth has been experiencing a rapid temperature increase over the past hundred years. There is ample scientific evidence from multiple sources that this is caused by the increase in carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere, which has seen a 50% increase over the historical levels in just hundred years (Figure 2). Carbon dioxide is one of the greenhouse gases which traps heat from the sun and slows the natural cooling process of the earth. This increase of carbon dioxide is due to human activities: fossil fuel burning, industrial processes, deforestation, and agricultural practices. Ironically, those who suffer from the consequences did not contribute to these changes; those who did contribute are trying their best to convince the world that the temperature changes we see are natural, and nothing should be done. We must have no illusions that global warming is a human-caused phenomenon, and it has serious repercussions.

(See Figure 2. Global Temperature and Carbon Dioxide Levels)

Why should we care about global warming? Well, there are many reasons, but let us focus on earth’s water cycle. Middle schoolers know that water evaporates from the oceans, rises into the atmosphere where it cools, condenses, and falls back onto earth as rain or snow. When the oceans warm, the evaporation increases, and the warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour. Water laden atmosphere results in severe and erratic weather. Ironically, water vapour is also a greenhouse gas, and this has a snowballing effect. The increased ocean temperature also disrupts ocean currents that influence the weather on land. The combined result is extreme and severe weather: violent storms and droughts depending on the geographic location. What is happening on the West coast of the USA is an example. The net result will be major departures from what is considered normal weather over millennia.

International organisations have been talking for 30 years about limiting global temperature increase to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels by curtailing greenhouse gas emissions. But not much has been done and the temperature has risen by 1.2oC already. The challenge is that even if we can stop greenhouse gas emissions completely, right now, we have the problem of removing already existing 2,500 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere, for which there are no practical solutions yet. Scientists worry about the consequences of runaway temperature increase and its effect on human life, which are many. It is not a doomsday prediction of life disappearing from earth, but a warning that life will be quite different from what humans are used to. All small tropical nations like ours are burdened with mitigating the consequences; in other words, get ready for more Ditwahs, do not wait for the twelve-day forecast.

Some opined that not enough warning was given regarding Ditwah; the truth is that the tools available for long-term prediction of the path or severity of a weather event (cyclone, typhoon, hurricane, tornado) are not perfect. There are multitude of rapidly changing factors contributing to the behavior of weather events. Meteorologists feed most up to date data to different computer models and try to identify the prediction with the highest probability. The multiple predictions for the same weather event are represented by what is known as spaghetti plots. Figure 3 shows the forecasted paths of a 2019 Atlantic hurricane five days ahead on the right and the actual path it followed on the left. While the long-term prediction of the path of a cyclone remains less accurate, its strength can vary within hours. There are several Indian ocean cyclones tracking sites online accessible to the public.

Figure 3. Forecasting vs Reality

There is no argument that short-term forecasts of this nature are valuable in saving lives and movable assets, but having long term plans in place to mitigate the effects of natural disasters is much more important than that. If a sizable section of the population must start over their lives from ground zero after every storm, how can a country economically develop?

The degree of our unpreparedness came to light during Ditwah disaster. It is not for lack of awareness; judging by the deluge of newspaper articles, blogs, vlogs, and speeches made, there is no shortage of knowledge and technical expertise to meet the challenge. The government has assured the necessary resources, and there is good reason to trust that the funds will be spent properly and not to line the pockets as happened during previous disasters. However, history tells us that despite the right conditions and good intentions, we could miss the opportunity again. Reasons for such skepticisms emerged during the few meetings the President held with the bureaucrats while visiting effected areas. Also, the COPE committee meetings plainly display the inherent inefficiencies and irregularities of our system and the absence of work ethics among all levels of the bureaucracy.

What it tells us is that we as a nation have an attitude problem. There are ample scholarly analyses by local as well as international researchers on this aspect of Sri Lankan psyche, and they label it as either island or colonial mentality. The first refers to the notion of isolated communities perceiving themselves as exceptional or superior to the rest of the world, and that the world is hell-bent on destroying or acquiring what they have. This attitude is exacerbated by the colonial mentality that promoted the divide and conquer rules and applied it to every societal characteristic imaginable; and plundered natural resources. As a result, now we are divided along ethnic, linguistic, religious, political, class, caste, geography, wealth, and many more real and imagined lines. Sadly, politicians, some religious leaders, and other opportunists keep inflaming these sentiments for their benefit when most of the population is willing to move on.

The first wish, therefore, is to get the strength, courage, and wisdom to think rationally, and discard outdated and outmoded belief systems that hinder our progress as a nation. May we get the courage to stop venerating elite who got there by exploiting the masses and the country’s wealth. More importantly, may we get the wisdom to educate the next generation to be free thinkers, give them the power and freedom to reject fabrications, myths, and beliefs that are not based on objective facts.

This necessitates altering our attitude towards many aspects of life. There is no doubt that free thinking does not come easily, it involves the proverbial ‘exterminating the consecrated bull.’ We are rightfully proud about our resplendent past. It is true that hydraulic engineering, art, and architecture flourished during the Anuradhapura period.

However, for one reason or another, we have lost those skills. Nowadays, all irrigation projects are done with foreign aid and assistance. The numerous replicas of the Avukana statue made with the help of modern technology, for example, cannot hold a candle to the real one. The fabled flying machine of Ravana is a figment of marvelous imagination of a skilled poet. Reality is that today we are a nation struggling with both natural and human-caused disasters, and dependent on the generosity of other nations, especially our gracious neighbor. Past glory is of little help in solving today’s problems.

Next comes national unity. Our society is so fragmented that no matter how beneficial a policy or an idea for the nation could be, some factions will oppose it, not based on facts, but by giving into propaganda created for selfish purposes. The island mentality is so pervasive, we fail to trust and respect fellow citizens, not to mention the government. The result is absence of long-term planning and stability. May we get the insight to separate policy from politics; to put nation first instead of our own little clan, or personal gains.

With increasing population and decreasing livable and arable land area, a national land management system becomes crucial. We must have an intelligent zoning system to prevent uncontrolled development. Should we allow building along waterways, on wetlands, and road easements? Should we not put the burden of risk on the risk takers using an insurance system instead of perpetual public aid programs? We have lost over 95% of the forest cover we had before European occupation. Forests function as water reservoirs that release rainwater gradually while reducing soil erosion and stabilizing land, unlike monocultures covering the hill country, the catchments of many rivers. Should we continue to allow uncontrolled encroachment of forests for tourism, religious, or industrial purposes, not to mention personal enjoyment of the elite? Is our use of land for agricultural purposes in keeping with changing global markets and local labor demands? Is haphazard subsistence farming viable? What would be the impact of sea level rising on waterways in low lying areas?

These are only a few aspects that future generations will have to grapple with in mitigating the consequences of worsening climate conditions. We cannot ignore the fact that weather patterns will be erratic and severe, and that will be the new normal. Survival under such conditions involves rational thinking, objective fact based planning, and systematic execution with long term nation interests in mind. That cannot be achieved with hanging onto outdated and outmoded beliefs, rituals, and traditions. Weather changes are not caused by divine interventions or planetary alignments as claimed by astrologers. Let us resolve to lay the foundation for bringing up the next generation that is capable of rational thinking and be different from their predecessors, in a better way.

by Geewananda Gunawardana

Features

From Diyabariya to Duberria: Lanka’s Forgotten Footprint in Global Science

For centuries, Sri Lanka’s biological knowledge travelled the world — anonymously. Embedded deep within the pages of European natural history books, Sinhala words were copied, distorted and repurposed, eventually fossilising into Latinised scientific names of snakes, bats and crops found thousands of kilometres away.

Africa’s reptiles, Europe’s taxonomic catalogues and global field guides still carry those echoes, largely unnoticed and uncredited.

Now, a Sri Lankan herpetologist is tracing those forgotten linguistic footprints back to their source.

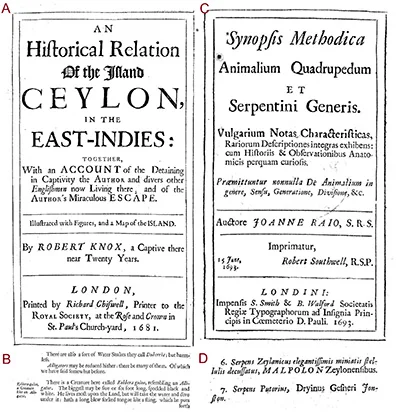

Through painstaking archival research into 17th- and 18th-century zoological texts, herpetologist and taxonomic researcher Sanjaya Bandara has uncovered compelling evidence that several globally recognised scientific names — long assumed to be derived from Greek or Latin — are in fact rooted in Sinhala vernacular terms used by villagers, farmers and hunters in pre-colonial Sri Lanka.

“Scientific names are not just labels. They are stories,” Bandara told The Island. “And in many cases, those stories begin right here in Sri Lanka.”

Sanjaya Bandara

At the heart of Bandara’s work is etymology — the study of word origins — a field that plays a crucial role in zoology and taxonomy.

While classical languages dominate scientific nomenclature, his findings reveal that Sinhala words were quietly embedded in the foundations of modern biological classification as early as the 1700s.

One of the most striking examples is Ahaetulla, the genus name for Asian vine snakes. “The word Ahaetulla is not Greek or Latin at all,” Bandara explained. “It comes directly from the Sinhala vernacular used by locals for the Green Vine Snake.” Remarkably, the term was adopted by Carl Linnaeus himself, the father of modern taxonomy.

Another example lies in the vespertilionid bat genus Kerivoula, described by British zoologist John Edward Gray. Bandara notes that the name is a combination of the Sinhala words kiri (milky) and voula (bat). Even the scientific name of finger millet, Eleusine coracana, carries linguistic traces of the Sinhala word kurakkan, a cereal cultivated in Sri Lanka for centuries.

Yet Bandara’s most intriguing discoveries extend far beyond the island — all the way to Africa and the Mediterranean.

In a research paper recently published in the journal Bionomina, Bandara presented evidence that two well-known snake genera, Duberria and Malpolon, both described in 1826 by Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger, likely originated from Sinhala words.

The name Duberria first appeared in Robert Knox’s 1681 account of Ceylon, where Knox refers to harmless water snakes called “Duberria” by locals. According to Bandara, this was a mispronunciation of Diyabariya, the Sinhala term for water snakes.

“Mispronunciations are common in Knox’s writings,” Bandara said. “English authors of the time struggled with Sinhala phonetics, and distorted versions of local names entered European literature.”

Over time, these distortions became formalised. Today, Duberria refers to African slug-eating snakes — a genus geographically distant, yet linguistically tethered to Sri Lanka.

Bandara’s study also proposes the long-overdue designation of a type species for the genus, reviving a 222-year-old scientific name in the process.

Equally compelling is the case of Malpolon, the genus of Montpellier snakes found across North Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe. Bandara traced the word back to a 1693 work by English zoologist John Ray, which catalogued snakes from Dutch India — including Sri Lanka.

“The term Malpolon appears alongside Sinhala vernacular names,” Bandara noted. “It is highly likely derived from Mal Polonga, meaning ‘flowery viper’.” Even today, some Sri Lankan communities use Mal Polonga to describe patterned snakes such as the Russell’s Wolf Snake.

Bandara’s research further reveals Sinhala roots in the African Red-lipped Herald Snake (Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia), whose species name likely stems from Hothambaya, a regional Sinhala term for mongooses and palm civets.

“These findings collectively show that Sri Lanka was not just a source of specimens, but a source of knowledge,” Bandara said. “Early European naturalists relied heavily on local names, local guides and local ecological understanding.”

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

“What is remarkable,” Bandara reflected, “is that these words travelled across continents, entered global usage, and remained there — often stripped of their original meanings.”

For Bandara, restoring those meanings is about more than taxonomy. It is about reclaiming Sri Lanka’s rightful place in the history of science.

“With this study, three more Sinhala words formally join scientific nomenclature,” he said.

“Who would have imagined that a Sinhala word would be used to name a snake in Africa?”

Long before biodiversity hotspots became buzzwords and conservation turned global, Sri Lanka’s language was already speaking through science — quietly, persistently, and across continents.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Children first – even after a disaster

However, the children and their needs may be forgotten after a disaster.

Do not forget that children will also experience fear and distress although they may not have the capacity to express their emotions verbally. It is essential to create child-friendly spaces that allow them to cope through play, draw, and engage in supportive activities that help them process their experiences in a healthy manner.

The Institute for Research & Development in Health & Social Care (IRD), Sri Lanka launched the campaign, titled “Children first,” after the 2004 Tsunami, based on the fundamental principle of not to medicalise the distress but help to normalise it.

The Island picture page

The IRD distributed drawing material and play material to children in makeshift shelters. Some children grabbed drawing material, but some took away play material. Those who choose drawing material, drew in different camps, remarkably similar pictures; “how the tidal wave came”.

“The Island” supported the campaign generously, realising the potential impact of it.

The campaign became a popular and effective public health intervention.

“A public health intervention (PHI) is any action, policy, or programme designed to improve health outcomes at the population level. These interventions focus on preventing disease, promoting health, and protecting communities from health threats. Unlike individual healthcare interventions (treating individuals), which target personal health issues, public health interventions address collective health challenges and aim to create healthier environments for all.”

The campaign attracted highest attention of state and politicians.

The IRD continued this intervention throughout the protracted war, and during COVID-19.

The IRD quick to relaunch the “children first” campaign which once again have received proper attention by the public.

While promoting a public health approach to handling the situation, we would also like to note that there will be a significant smaller percentage of children and adolescents will develop mental health disorders or a psychiatric diagnosis.

We would like to share the scientific evidence for that, revealed through; the islandwide school survey carried out by the IRD in 2007.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

The authors concluded that exposure to traumatic events may have a detrimental effect on subsequent school attendance. This may give rise to perpetuating socioeconomic inequality and needs further research to inform policy and intervention.

Even though, this small but significant percentage of children with psychiatric disorders will need specialist interventions, psychological treatment more than medication. Some of these children may complain of abdominal pain and headaches or other physical symptoms for which doctors will not be able to find a diagnosable medical cause. They are called “medically unexplained symptoms” or “somatization” or “bodily distress disorder”.

Sri Lanka has only a handful of specialists in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders but have adult psychiatrists who have enough experience in supervising care for such needy children. Compared to tsunami, the numbers have gone higher from around 20 to over 100 psychiatrists.

Most importantly, children absent from schools will need more close attention by the education authorities.

In conclusion, going by the principles of research dissemination sciences, it is extremely important that the public, including teachers and others providing social care, should be aware that the impact of Cyclone Ditwah, which was followed by major floods and landslides, which is a complex emergency impact, will range from normal human emotional behavioural responses to psychiatric illnesses. We should be careful not to medicalise this normal distress.

It’s crucial to recall an important statement made by the World Health Organisation following the Tsunam

Prof. Sumapthipala MBBS, DFM, MD Family Medicine, FSLCFP (SL), FRCPsych, CCST (UK), PhD (Lon)]

Director, Institute for Research and Development in Health and Social Care, Sri Lanka

Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Keele University, UK

Emeritus Professor of Global Mental Health, Kings College London

Secretary General, International society for Twin Studies

Visiting Professor in Psychiatry and Biomedical Research at the Faculty of Medicine, Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka

Associate Editor, British Journal Psychiatry

Co-editor Ceylon Medical Journal.

Prof. Athula Sumathipala

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoA very sad day for the rule of law

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoUS Ambassador to Sri Lanka among 29 career diplomats recalled