Life style

How This Demon Dance Banishes Illnesses

in Sri Lanka’s Remote Jungles

by Zinara Ratnayake

The kankariya dance all started with a legendary demon queen named Kuweni. As dusk falls, the thumping sound of drums echoes through the jungles of central Sri Lanka. Elaborately dressed dancers spin and swirl as their ornate silver headpieces gleam and bright red ribbons trail behind them. Their chests rise and fall beneath silver-beaded breastplates and two large mango-shaped earrings adorn their ears. The dancers carry candle-lit, hollowed-out coconuts and chant verses inviting gods and demons to their ritual. Sweet-smelling smoke from jasmine incense fills the air, obscuring the view of a banana bark altar with pictures of various Buddhist deities. As hundreds gather, the dancers tell the sad tale of the mythic, magical queen Kuweni.

This is kohomba yak kankariya. Several times a year, often in April, Sri Lankans in the country’s mountainous, central region hold this ritual to cure illnesses, prevent diseases from spreading, and seek blessings from the supernatural world. While today the ceremony tells Kuweni’s story, whose name is sometimes spelled Kuveni or Sesapathi, in ancient times, the ritual was believed to have lifted the illness-causing curse Kuweni had placed on the province.

According to legend, Kuweni was born in the sixth century BC to a yakka king who ruled Sri Lanka. The Sinhala word yakka is derived from the Pali word yakkha (Pali is a liturgical language often used in Buddhist texts) and the Sanskrit term yaksha, which translates to “demon.” Dipavamsa, the oldest historical account of Sri Lanka, describes yakka as a disorderly tribe of demons who eat human flesh and fight with each other. Although her father was a demon, Kuweni may not have been one herself.

Then Prince Vijaya, a legendary Indian prince, and 700 of his followers invaded demon-controlled Sri Lanka. Kuweni appeared before the prince disguised as a hermit spinning cotton. Vijaya soon promised to marry Kuweni and make her his queen. Trusting him, she betrayed her father and demon brethren and helped the prince slaughter them. Only a few of the yakka escaped into the Sri Lankan jungles.

Queen Kuweni was said to stalk the nightmares of King Vijaya’s nephew, Panduwas, in the form of a powerful leopardess.

After Vijaya took power, he broke his promise to Kuweni and married a South Indian princess, establishing the Sinhalese people who today make up the majority of Sri Lanka’s population. Jilted and angry, Kuweni cursed Vijaya and his successors before the remaining yakka killed her out of revenge.

Later, when Vijaya’s nephew Panduwas arrived in Sri Lanka to take the throne as his uncle’s successor, Panduwas began to suffer from a mysterious illness. He couldn’t sleep. Night after night, Kuweni, in the form of a leopard, appeared in his dreams and tried to kill him. Sleep deprivation drove Panduwas insane. Kuweni finally had her revenge.

In his book Kohomba Kankariya: The Sociology of a Kandyan Ritual, social anthropologist Sarath Amunugama wrote that Kuweni’s leopard is “a symbolic representation of the fatal lie that was uttered by Vijaya to Kuweni to facilitate his conquest.” Panduwas suffered due to his uncle’s lie to the queen, wrote Amunugama.

When Lord Sakra, the ruler of heaven in Buddhist cosmology, sees Panduwas unjustly suffering for his uncle’s deceit, he tells an Indian king about a ritual that will cure the ailing Panduwas. The king performs the ritual, and Panduwas recovers. Later on, the king instructed a local prince named Kohomba to perform the ritual any time it was necessary to repel Kuweni’s illness-fueling ire. Since then, the ritual, called kohomba yak kankariya in honour of the prince, is performed any time a mysterious illness descends upon the community.

Today, folk priests—village priests who conduct ancient rites such as the kankariya—continue to perform the ritual dance whenever local communities are plagued with diseases, such as chickenpox. One such priest is 29-year-old Abheeth Shilpadhipathi, whose father and grandfather taught him the kankariya. Recently, when Shilpadhipathi drummed in a kankariya, it was to ward off the Covid-19 pandemic that plagued the country. Originally, the ceremony would’ve lasted for about seven days, but today it takes less than a day.

“Before [the kankariya] begins, the chief [folk] priest pledges to the gods their intention in conducting the ceremony,” Shilpadhipathi says. In the past, individual families performed a kankariya to cure diseases, but because it’s an elaborate, expensive event, families rarely host them anymore. Buddhist temples and large social groups now conduct them annually or seasonally both as a healing and fertility ritual and sometimes just to keep the tradition alive. “People do it to show their gratitude for a good harvest or good fortune,” says Shilpadhipathi.

A Hindu priest holds a lit coconut oil lamp in front of statues of Prince Vijaya (left) and Kuweni (right) at the Sri Subramaniam temple in the southern Sri Lankan town of Matara.

People also perform the kankariya ritual to bestow good health, wealth, and even good school grades, says Sanushki Athalage, choreographer at Thaala Asapuwa, a Sri Lankan Dance Academy in Victoria, Australia, where they teach the kankariya along with other traditional dances. “It is also about giving and being selfless in return for a prosperous life. It is a beautiful concept that brings larger communities together in a common goal,” Athalage says.

Buddhism in Sri Lanka is a complex system that incorporates “shrines, rituals, and priests” who negotiate with a vast pantheon of gods, deities, and demons, says Amunugama. Sri Lankan Buddhists believe that prayers and rituals, such as the kankariya, are a way to seek blessings and build good karma.

Religious ceremonies are also a way to prevent meddlesome demons from interfering in people’s lives. Kuweni isn’t the only entity that can cause illnesses. Local folklore is full of demons who hunt humans and make them ill. When someone becomes sick, local priests are called in to identify the specific demon causing the illness. Once identified, the priest summons and vanquishes the demon in a dance or ritual, similar to the kankariya.

One popular ritual performed in southern Sri Lanka is the Daha Ata Sanniya, which is sort of a catch-all ritual that can cure illnesses caused by 18 different demons.

Rituals like these are “performed to relieve anxieties around mysterious diseases,” says Athalage. “When families are anxious, they seek blessings and help from higher powers to cure something that they don’t understand.” For the villagers, this “excursion into the supernatural” will help them live a “relatively untroubled life,” wrote Amunugama in his book. These rituals are a way to understand the incomprehensible, like why a loved one falls ill.

Although Kuweni caused illnesses like other demons, Shashiprabha Thilakarathne, a folklore scholar at the University of Moratuwa in Sri Lanka who researches Kuweni, explains that the demon queen might’ve been human. “It’s difficult to say who she is. Folk literature tells us that she has supernatural powers. Sometimes she could even take the form of different animals,” Thilakarathne says, explaining that her “magic” made “Vijaya’s weapons fall on demons’ bodies.”

But in the last few decades, Kuweni has appeared as a character in pop culture, from television dramas to songs and plays. Kuweni has become relatable—her motives clearer. Today Vijaya is often recast as the villain and Kuweni as the maligned anti-hero. She has shifted from a female demon spawn who cursed Sinhalese people to an embodiment of the modern woman, Thilakarathne explains. She is a wife, daughter, and mother. While Kuweni shares many traits with traditional yakka, she also stands out from them. She’s demon-like, but not a demon herself.

“Kuweni, as I understand, is a model we can apply to our modern society. At one point, she’s a daughter, then a lover and parent. She goes through many different challenges in life,” Thilakarathne says, “she represents us.”(BBC)

Life style

Salman Faiz leads with vision and legacy

Salman Faiz has turned his family legacy into a modern sensory empire. Educated in London, he returned to Sri Lanka with a global perspective and a refined vision, transforming the family legacy into a modern sensory powerhouse blending flavours,colours and fragrances to craft immersive sensory experiences from elegant fine fragrances to natural essential oils and offering brand offerings in Sri Lanka. Growing up in a world perfumed with possibility, Aromatic Laboratories (Pvt) Limited founded by his father he has immersed himself from an early age in the delicate alchemy of fragrances, flavours and essential oils.

Salman Faiz did not step into Aromatic Laboratories Pvt Limited, he stepped into a world already alive with fragrance, precision and quiet ambition. Long before he became the Chairman of this large enterprise, founded by his father M. A. Faiz and uncle M.R. Mansoor his inheritance was being shaped in laboratories perfumed with possibility and in conversations that stretched from Colombo to outside the shores of Sri Lanka, where his father forged early international ties, with the world of fine fragrance.

Salman Faiz did not step into Aromatic Laboratories Pvt Limited, he stepped into a world already alive with fragrance, precision and quiet ambition. Long before he became the Chairman of this large enterprise, founded by his father M. A. Faiz and uncle M.R. Mansoor his inheritance was being shaped in laboratories perfumed with possibility and in conversations that stretched from Colombo to outside the shores of Sri Lanka, where his father forged early international ties, with the world of fine fragrance.

Growing up amidst raw materials sourced from the world’s most respected fragrance houses, Salman Faiz absorbed the discipline of formulation and the poetry of aroma almost by instinct. When Salman stepped into the role of Chairman, he expanded the company’s scope from a trusted supplier into a fully integrated sensory solution provider. The scope of operations included manufacturing of flavours, fragrances, food colours and ingredients, essential oils and bespoke formulations including cosmetic ingredients. They are also leading supplier of premium fragrances for the cosmetic,personal care and wellness sectors Soon the business boomed, and the company strengthened its international sourcing, introduced contemporary product lines and extended its footprint beyond Sri Lanka’s borders.

Today, Aromatic Laboratories stands as a rare example of a second generation. Sri Lankan enterprise that has retained its soul while embracing scale and sophistication. Under Salman Faiz’s leadership, the company continues to honour his father’s founding philosophy that every scent and flavour carries a memory, or story,and a human touch. He imbibed his father’s policy that success was measured not by profit alone but the care taken in creation, the relationships matured with suppliers and the trust earned by clients.

“We are one of the leading companies manufacturing fragrances, dealing with imports,exports in Sri Lanka. We customise fragrances to suit specific applications. We also source our raw materials from leading French company Roberte’t in Grasse

Following his father, for Salman even in moments of challenge, he insisted on grace over haste, quality over conveniences and long term vision over immediate reward under Salman Faiz’s stewardship the business has evolved from a trusted family enterprise into a modern sensory powerhouse.

Now the company exports globally to France, Germany, the UK, the UAE, the Maldives and collaborates with several international perfumes and introduces contemporary products that reflect both sophistication and tradition.

We are one of the leading companies. We are one of the leading companies manufacturing fine and industrial fragrance in Sri Lanka. We customise fragrances to suit specific applications said Faiz

‘We also source our raw materials from renowned companies, in Germany, France, Dubai,Germany and many others.Our connection with Robertet, a leading French parfume House in Grasse, France runs deep, my father has been working closely with the iconic French company for years, laying the foundation for the partnership, We continue even today says Faiz”

Today this business stands as a rare example of second generation Sri Lankan entrepreneurship that retains its souls while embracing scale and modernity. Every aroma, every colour and every flavour is imbued with the care, discipline, and vision passed down from father to son – a living legacy perfected under Salmon Faiz’s guidance.

By Zanita Careem

Life style

Home coming with a vision

Harini and Chanaka cultivating change

When Harini and Chanaka Mallikarachchi returned to Sri Lanka after more than ten years in the United States, it wasn’t nostalgia alone that they brought home . It was purpose.Beneath the polished resumes and strong computer science backgrounds lay something far more personal- longing to reconnect with the land, and to give back to the country that shaped their memories. From that quiet but powerful decision was born Agri Vision not just an agricultural venture but a community driven movement grounded in sustainability ,empowerment and heritage. They transform agriculture through a software product developed by Avya Technologies (Pvt Limited) Combining global expertise with a deep love for their homeland, they created a pioneering platform that empowers local farmers and introduce innovative, sustainable solutions to the country’s agri sector.

After living for many years building lives and careers in theUnited States, Harini and Chanaka felt a powerful pull back to their roots. With impressive careers in the computer and IT sector, gaining global experience and expertise yet, despite their success abroad, their hearts remained tied to Sri Lanka – connection that inspired their return where they now channel their technological know-how to advance local agriculture.

For Harini and Chanaka, the visionaries behind Agri Vision are redefining sustainable agriculture in Sri Lanka. With a passion for innovation and community impact, they have built Agri Vision into a hub for advanced agri solutions, blending global expertise with local insight.

In Sri Lanka’s evolving agricultural landscape, where sustainability and authenticity are no longer optional but essential. Harini and Chanaka are shaping a vision that is both rooted and forward looking. In the heart of Lanka’s countryside, Uruwela estate Harini and Chanaka alongside the ever inspiring sister Malathi, the trio drives Agri Vision an initiative that fuses cutting edge technology with age old agricultural wisdom. At the core of their agri philosophy lies two carefully nurtured brands artisan tea and pure cinnamon, each reflecting a commitment to quality, heritage and people.

Armed with global exposure and professional backgrounds in the technology sector,they chose to channel thier experiences into agriculture, believing that true progress begins at home.

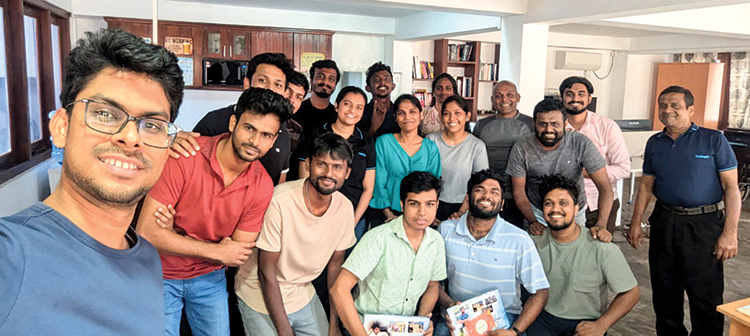

- Avya Technologies (Pvt) ltd software company that developed Agri Vision

- Chanaka,Harini and Shakya Mallikarachchi and Malathi Malathi dias (middle)

But the story of Agri Vision is as much about relationships as it is about technology. Harini with her sharp analytical mind, ensures the operations runs seamlessly Chanaka, the strategist looks outward, connecting Agri Vision to globally best practices and Malathi is their wind behind the wings, ensures every project maintains a personal community focussed ethos. They cultivate hope, opportunity and a blueprint for a future where agriculture serves both the land and the people who depend on it .

For the trio, agriculture is not merely about cultivation, it is about connection. It is about understanding the rhythm of the land, respecting generations of farming knowledge, and that growth is shared by the communities that sustain it. This belief forms the backbone of Agro’s vision, one that places communities not only on the periphery, but at the very heart of every endeavour.

Artisan tea is a celebration of craft and origin sourced from selected growing regions and produced with meticulous attention to detail, the tea embodier purity, traceability and refinement, each leaf is carefully handled to preserve character and flavour, reflecting Sri Lanka’s enduring legacy as a world class tea origin while appealing to a new generation of conscious consumers complementing this is pure Cinnamon, a tribute to authentic Ceylon, Cinnamon. In a market saturated with substitutes, Agri vision’s commitment to genuine sourcing and ethical processing stands firm.

By working closely with cinnamon growers and adhering to traditional harvesting methods, the brands safeguards both quality and cultural heritage.

What truly distinguishes Harini and Chanake’s Agri Vision is their community approach. By building long term partnerships with smallholders. Farmers, the company ensures fair practises, skill development and sustainable livelihoods, These relationships foster trust and resilience, creating an ecosystem where farmers are valued stakeholders in the journey, not just suppliers.

Agri vision integrates sustainable practices and global quality standards without compromising authenticity. This harmony allows Artisan Tea and Pure Cinnamon to resonate beyond borders, carrying with them stories of land, people and purpose.

As the brands continue to grow Harini and Chanaka remain anchored in their founding belief that success of agriculture is by the strength of the communities nurtured along the way. In every leaf of tea and every quill of cinnamon lies a simple yet powerful vision – Agriculture with communities at heart.

By Zanita Careem

Life style

Marriot new GM Suranga

Courtyard by Marriott Colombo has welcomed Suranga Peelikumbura as its new General Manager, ushering in a chapter defined by vision, warmth, and global sophistication.

Suranga’s story is one of both breadth and depth. Over two decades, he has carried the Marriott spirit across continents, from the shimmering luxury of The Ritz-Carlton in Doha to the refined hospitality of Ireland, and most recently to the helm of Resplendent Ceylon as Vice President of Operations. His journey reflects not only international mastery but also a devotion to Sri Lanka’s own hospitality narrative.

What distinguishes Suranga is not simply his credentials but the philosophy that guides him. “Relationships come first, whether with our associates, guests, partners, or vendors. Business may follow, but it is the strength of these connections that defines us.” It is this belief, rooted in both global perspective and local heart, that now shapes his leadership at Courtyard Colombo.

At a recent gathering of corporate leaders, travel partners, and media friends, Suranga paid tribute to outgoing General Manager Elton Hurtis, hon oring his vision and the opportunities he created for associates to flourish across the Marriott world. With deep respect for that legacy, Suranga now steps forward to elevate guest experiences, strengthen community ties, and continue the tradition of excellence that defines Courtyard Colombo.

From his beginnings at The Lanka Oberoi and Cinnamon Grand Colombo to his leadership roles at Weligama Bay Marriott and Resplendent Ceylon, Suranga’s career is a testament to both resilience and refinement. His return to Marriott is not merely a professional milestone, it is a homecoming.

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIMF MD here