Opinion

From tradition to transformation: Sri Lanka’s coconut export revolution

By Randeewa Malalasooriya

President

Coconut Milk Manufacturers’ Association

In recent times, Sri Lanka has been rethinking its approach to exports in response to global economic changes. It’s moving away from its traditional exports like tea and rubber and exploring new avenues to make the most of its rich agricultural resources.

Coconut: A Versatile Agricultural Resource

Among the main agricultural exports, coconut is one such resource that has numerous opportunities. Coconuts, deeply ingrained in Sri Lanka’s agricultural heritage, are now at the forefront of this transformation. These versatile fruits play a vital role, contributing approximately 12% to the nation’s overall agricultural output.

Abundance and Demand

Sri Lanka has an annual coconut crop of 2.8 to 3.2 billion nuts, according to CRI statistics. Yet, this abundance falls short of the annual requirement of 4.6 billion nuts, a demand driven by domestic consumption, coconut oil production, and exports.

Global Recognition in the Coconut Industry

On the global stage, Sri Lanka has gained recognition in the coconut industry, primarily through products like Desiccated Coconut (DC) and brown fiber. The nation’s DC stands out with its distinct white color and exquisite taste, securing Sri Lanka’s position as the fourth-largest exporter of kernel products worldwide. Additionally, Sri Lanka excels in brown fiber production, known for its exceptionally long and pristine strands, making it the world’s leading exporter in this category, even finding applications in the brush industry.

Embracing the Global Shift Towards Healthier Alternatives

However, the most remarkable aspect of this transformation is Sri Lanka’s shift from traditional exports to innovative and value-added coconut products. This transition underscores not only adaptability but also the immense potential that coconuts offer as a versatile and lucrative export commodity.

In an era where global preferences are shifting towards healthier, plant-based alternatives, coconut-based products, especially coconut milk, are experiencing an unprecedented surge in demand. Embracing this transformative wave allows Sri Lanka to maximise its abundant coconut resources and align perfectly with the evolving tastes and desires of global consumers.

The Booming Demand for Coconut Milk

In such a backdrop, the potential for export revenue from coconut milk is staggering. Sri Lanka could tap into international markets hungry for this creamy delight. Beyond its renown in culinary applications, Sri Lankan coconut milk, extracted by pressing grated fresh coconut kernel, has garnered global demand. It is available in various forms, including undiluted and diluted liquid versions, as well as skimmed and spray-dried powder forms.

Meeting the Needs of Health-Conscious Consumers

The production of coconut skimmed milk, obtained through centrifugal separation to remove fat, provides a high-quality protein source, ideal for various food products. This aligns with current global trends, such as vegan, gluten-free, and soy-free foods, contributing to the surge in popularity of coconut milk as a dairy milk substitute. Sri Lanka has capitalized on this opportunity by manufacturing and exporting a wide range of flavored and unflavored drinking coconut milk to the world. Sri Lankan coconut milk stands out in the world market due to its distinct white hue, unique aroma, and delectable flavor.

Steady Growth in Export Earnings

The demand for coconut milk, with its diverse culinary applications and growing popularity in global cuisines, is on the rise. Export earnings from coconut milk have steadily climbed, providing a ray of hope in an otherwise challenging economic landscape.

Efficiency Gains Through Industrialization

Traditional methods of extracting coconut milk involve grating the coconut kernel and manually squeezing the fresh meat to yield the milk. However, this age-old practice results in significant economic loss, with only 30 to 40 percent of the coconut’s potential value being realized compared to industrial methods.

Comparing domestic and industrial milk extraction, the disparities become glaringly evident. While domestic usage recovers only 15 to 20 percent of the coconut’s fat content, industrial methods boast a more efficient 30 to 35 percent recovery rate. The residue from domestic extraction often goes to waste, whereas in industrial settings, it’s repurposed or sold. Even coconut water, shells, and parings, which are discarded domestically, find productive use in industrial applications like activated carbon production and oil production.

Maximising Coconut Resources

Despite the shortfall of 1.4 to 1.6 billion coconuts, the nation still uses 1.8 billion coconuts domestically, primarily for culinary purposes. By reallocating a larger portion of this consumption for the production of industrial value-added products like coconut milk and coconut cream, Sri Lanka could harness its coconut resources more efficiently.

Multifaceted Benefits

The benefits of such a shift are multifaceted. Factories could supply high-quality, safe, and value-added products for domestic consumption, often additive-free and organic, mitigating health concerns. Sri Lanka could also bolster its foreign exchange reserves through improved exports of coconut-based products.

By reevaluating the role of coconuts in both its cultural and economic narrative, the nation can bridge the gap between abundance and scarcity, transforming its coconut resources into a source of prosperity and sustainability.

A Vision for Economic Growth

In 2019, Sri Lanka faced a local oil requirement of 140,000 metric tons, with a substantial portion being imported, equivalent to a staggering 840 million kilos of coconuts, or roughly 1.4 billion nuts. This substantial coconut resource was harnessed to produce 240 million kilos of coconut milk, valued at USD 480 million (approximately Rs. 91.2 billion).

This transformation from coconuts to coconut milk not only created a value addition of USD 126 million (around Rs. 24.5 billion) but also generated a net profit of Rs. 66.7 billion or USD 354 million. These statistics highlight the immense economic potential that Sri Lanka can unlock by maximising the use of its coconut resources, not only meeting local demands but also creating profitable opportunities through value addition.

Innovative Proposals for Economic Growth

To bolster Sri Lanka’s economy through its coconut kernel industry, a groundbreaking proposal has emerged: the implementation of a value-based rebate certificate system. Under this proposal, manufacturers of coconut kernel-based products would be granted tax quotas of Rs. 50 for importing coconut oil, with the allocation determined by their contribution to exports. This allocation could be based on the foreign revenue they bring into the country or the volume they export.

Efficient Resource Allocation

Consider an example of a revenue-based quota system, where one kilo of quota is granted for every $4 in foreign revenue generated. In this scenario, the total foreign exchange earnings from the coconut kernel industry amount to an impressive USD 350 million. Using the revenue-based quota system, this translates to an allocation of 87.5 million kilos, equivalent to 87,500 metric tons of coconut oil to be imported. This imported oil would be sufficient for approximately 700 million coconuts.

Innovative Solutions to the Coconut

Shortage Predicament

From a cost perspective, the government’s investment in this system would be approximately LKR 4,375 million (or USD 21.8 million). However, considering Sri Lanka’s existing coconut shortage for both domestic consumption and industrial usage, this strategy presents an innovative solution. It would alleviate the coconut shortage predicament and allow for the allocation of more coconuts to produce value-added coconut kernel products, consequently boosting the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Economic Gains from Coconut Milk Production

By producing coconut milk from the 700 million allocated coconuts, this initiative could generate foreign revenue of USD 280 million. After deducting the initial government cost of USD 21.8 million, the net gain for the country would amount to USD 258.2 million. Simultaneously, the importation of fresh coconuts would bolster local coconut supplies, stabilizing prices for both farmers and consumers.

Addressing the Critical Deficit

The current expected foreign exchange revenue stands at an impressive $1.2 billion, with existing earnings from both kernel and non-kernel-based products at $400 million each. However, a critical $400 million deficit looms on the horizon.

Safeguarding Coconut Growers

To bridge this gap and secure a brighter future for Sri Lanka, the nation envisions importing fresh coconuts. These coconuts will be the raw materials for producing high-demand products like coconut milk, Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO), and Desiccated Coconut (DC). Each kilogram of coconut used in these processes promises significant foreign exchange gains, further enriching the nation’s coffers.

Preserving Local Coconut Farming Communities

This visionary proposal doesn’t just reflect economic ambition; it reflects a deep commitment to safeguarding local coconut growers. When coconut prices at the Colombo auction dip below the threshold of Rs. 65 per nut, imports can be judiciously curtailed. This safeguard is more than a mere economic maneuver; it’s a lifeline for local growers, preserving their livelihoods and maintaining a fair minimum price for their produce.

Ensuring Stable and Improved Income

Foremost among these advantages is the assurance of stable and improved income. Historically, coconut growers have grappled with the unpredictability of local coconut prices, which often fluctuate due to market dynamics. However, with the increase in coconut exports, demand for coconuts will rise, leading to higher and more stable prices for their produce. This means that coconut growers can look forward to a reliable source of income that not only sustains their livelihoods but elevates their economic well-being.

Coconut Exports in the Region: A Lesson in Economic Growth

Coconut exports in the region have been a significant driver of economic growth and stability for several countries, including Sri Lanka. Neighbouring nations such as Thailand and Indonesia have successfully leveraged their natural coconut resources to establish themselves as major players in the global coconut market.

Thailand, for instance, has become a leading exporter of coconut products such as coconut milk, coconut water, and coconut oil. The country’s coconut milk, known for its quality and taste, has gained popularity in international markets and is widely used in various cuisines. Thailand’s success in coconut exports has contributed to its economic growth and stability.

Indonesia, another regional powerhouse in coconut production, has also diversified its coconut exports. The country is a major exporter of products like coconut oil and desiccated coconut. Indonesia’s coconut oil, in particular, is in high demand globally, with applications in food, cosmetics, and industrial sectors.

Embracing Adaptability and

Pragmatism in Sri Lanka

These neighboring countries have not only bolstered their economies through coconut exports but have also made pragmatic choices like importing coconuts for domestic consumption. This strategic approach allows them to focus on producing high-value coconut-based products for the global market.

Coconut exports in the region, led by countries like Thailand and Indonesia, have demonstrated the economic potential of coconut-based products in the global market. Sri Lanka is following suit by diversifying its coconut exports, aligning with contemporary consumer preferences and global trends, and aiming for economic growth and sustainability.

Preserving Tradition and Promoting Sustainability

Sri Lanka, recognizing the success of its regional counterparts, is also shifting its focus towards coconut-based exports, particularly coconut milk. This shift reflects a broader change in mindset, emphasizing adaptability and pragmatism. By learning from its neighbors and maximizing the potential of coconut exports, Sri Lanka aims to unlock a future where coconuts are not wasted but celebrated as a valuable export commodity.

Promoting Sustainable Agriculture and Economic Prosperity

Furthermore, the expansion of coconut exports safeguards the future of these farming communities. By creating a more lucrative market for coconuts, this initiative encourages the younger generation to embrace coconut farming as a viable profession. This not only preserves the traditional knowledge and practices of coconut cultivation but also injects fresh energy into the industry, ensuring its continuity for generations to come.

The ripple effects of this growth extend beyond financial gains. With increased income and market stability, coconut growers can invest in the modernization of their farms, adopting advanced farming techniques and technologies. This not only enhances productivity but also promotes sustainable and eco-friendly farming practices, aligning with global demands for responsible agriculture.

Coconut Milk: A Sustainable Future

These countries’ success in coconut milk exports reflects the increasing popularity of coconut-based products, driven by global trends favoring healthier and plant-based food alternatives. As consumers worldwide continue to seek coconut milk for its culinary and health benefits, the region’s coconut-producing nations are poised to play a crucial role in meeting this demand and expanding their export markets further. Coconut milk exports are not only economically beneficial but also align with the shift towards sustainable and plant-based food options, making them a significant part of the region’s agricultural exports.

Unlocking Economic Advantages Through Coconut Milk Exports

Exporting coconut milk holds significant economic advantages for Sri Lanka. This strategic shift from traditional exports like tea and rubber diversifies the country’s export portfolio, reducing reliance on a few commodities and spreading economic risk. The global demand for coconut milk is on the rise, thanks to its versatile use in various cuisines and as a dairy milk substitute, providing Sri Lanka with an opportunity to tap into a lucrative market.

Adding Value and Promoting Sustainability

Moreover, processing coconut milk adds value to raw coconuts, enabling higher pricing and profit margins. This value addition contributes to increased revenue, strengthens foreign exchange reserves, and fosters job creation along the coconut milk production chain. Importantly, it stabilizes coconut prices for farmers and consumers, ensuring fair returns for agricultural efforts. By adapting to global food trends favoring healthier and plant-based options, Sri Lanka’s coconut milk exports not only boost the economy but also promote sustainability in the country’s rich coconut industry.

Conclusion: A Prosperous Path Forward

Sri Lanka’s journey towards coconut-based exports, especially coconut milk, is a transformative and forward-thinking approach that capitalizes on the nation’s abundant coconut resources. It offers economic growth, stability, and sustainability while preserving the cultural and agricultural heritage of coconut farming. This strategic shift holds the promise of a brighter future, when coconuts will be a global export commodity driving prosperity and well-being.

Opinion

Why is transparency underfunded?

The RTI Commission has now confirmed what many suspected — although the RTI Act grants it independence to recruit staff, this authority is rendered toothless because the Treasury controls the purse strings. The Commission is left operating with inadequate manpower, limiting its institutional growth even as it struggles to meet rising public demand for information.

This raises an uncomfortable question: if the Treasury can repeatedly allocate billions to loss-making State-Owned Enterprises — some of which continue to hemorrhage public funds without reform — why is adequate funding for the RTI Commission treated as optional?

Strengthening transparency is not a luxury. It is the foundation of good governance. Every rupee spent on effective oversight helps prevent many more rupees being wasted through inefficiency, misuse, or opaque decision-making.

In such a context, can one really fault those who argue that restricting the Commission’s resources conveniently limits disclosures that may prove politically inconvenient? Whether deliberate or not, the outcome is the same: weaker accountability, reduced public scrutiny, and a system where opacity is easier than openness.

If the government is serious about reform, it must start by funding the institutions that keep it honest. Investing in RTI is not an expense — it is a safeguard for the public purse and the public trust.

A Concerned Citizen – Moratuwa

Opinion

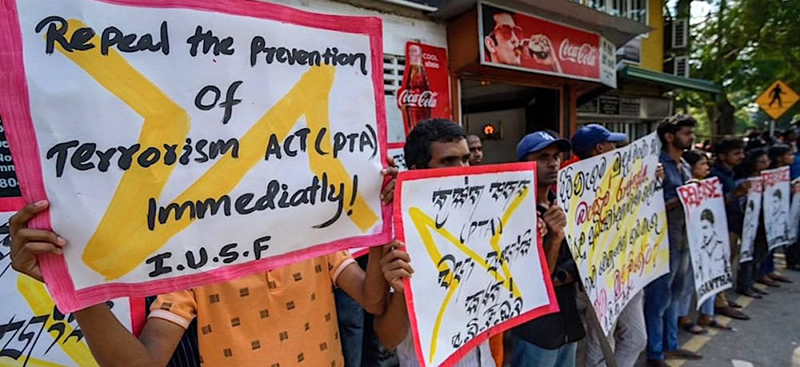

Protection of the state from terrorism act:a critique of the current proposal

I. Background to the Government Proposal

The Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act, No. 48 of 1979, (PTA), has been vigorously assailed for 45 years as the anchor of a legislative regime which is destructive of basic political and civil rights. It has gained ignominy as an instrument for denial of justice in diverse contexts and also placed in jeopardy, internationally, the prestige of our country as a vibrant democracy. There have been legislative interventions from time to time by Act No. 10 of 1982 and Act No. 22 of 1988.

By 2022, it was clear that the momentum of reform had to be accelerated. As Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time, on 22 March 2022, I introduced in Parliament, and secured the passage of, a series of amendments to the PTA. This was in the form of Act No. 12 of 2022. These amendments had as their principal objective, shortening the maximum period of permissible detention without trial, enhancing judicial oversight of detention, access to legal representation and communication, expediting of trials, liberalizing the law relating to bail, and invocation of the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in fundamental rights applications.

I made it clear in Parliament that this was only a preliminary step confined to the introduction of urgent amendments to address immediate concerns. The ultimate aim, I informed Parliament, was not ad-hoc modification of the existing law, but the enactment of all-encompassing, fresh legislation. Towards this end, a comprehensive review was underway with participation by the Ministries of Defence, Justice, and Foreign Affairs, and the Attorney General’s Department.

At the 50th session of the Human Rights Council on 13 June 2022, as Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka, I gave a firm assurance in Geneva that, pending this overhaul of the applicable legislation, there would be a de facto moratorium on use of the PTA. Although the Inspector General of Police had issued instructions accordingly at the time, unfortunately, after successive changes of government, this undertaking was not adhered to.

Three attempts have been made by different governments to enact complete legislation on terrorism. These were the Counter-Terrorism Act gazetted in September 2018, and two versions of an Anti-Terrorism Act in March and September 2023. On account of strong public resistance, none of these found their way into the statute book.

The current draft, Protection of the State from Terrorism Act, (PSTA), which has been in the making for almost a year, was published in December 2025. Notwithstanding the high level of expectation which it had generated, regrettably, the draft Bill fails, in fundamental respects, to advance the law towards justice and freedom.

II. Issues of Definition and Scope

One of the main weaknesses of the draft legislation is that it is entirely unsuccessful in addressing the pivotal issue of the legitimate boundaries of an extraordinary system of criminal liability which displaces seminal rights inherent in the Rule of Law. In all democratic cultures, it is recognized that imperatives of security in extreme circumstances call for measures incompatible with guarantees of freedom upheld by the regular law. The lines of demarcation, however, are of overriding importance. From this standpoint, the proposed legislation is a singular disappointment.

Structurally, in its very foundation, it contravenes criteria imposed by international human rights law. This is starkly evident in the approach of the draft Bill to definition of the mental ingredient in terrorism-related offences, one of the critical factors in containing liability within appropriate limits.

International law requires, in this context, a hybrid mental requirement consisting of a dual-layered intention to cause death, serious bodily harm, or taking of hostages but necessarily combined with the calculated intention of bringing about a reign of terror and intimidating the public. Both elements are compulsory requisites of liability for a terrorism-related offence. This fundamental postulate is breached by the proposed legislation which adopts the approach of requiring direct intention or knowledge in respect of the first element [section 3(1)], but regards the second as an oblique inference from a “consequence” such as the death of a person, hurt or hostage taking [section 3(2)]. Dramatic lowering of the threshold of responsibility by this mode of definition strikes at the root of the value system entrenched in international law.

The draft legislation creates no fewer than 13 categories of acts carrying the taint of terrorism. The compelling objection to this extensive catalogue is that it blurs the distinction between ordinary criminal acts and the stringently limited category of acts involving terrorism. The first, and indispensable, requirement of legislation in the latter field is that of clear and unambiguous definition with no scope for elasticity of interpretation. By vivid contrast, the draft law contains a multitude of offences which find their proper place in the Penal Code and other regular legislation, but are by no means necessarily susceptible to the label of terrorism. Egregious examples are serious damage to any place of public use or any public property; the offence of robbery, extortion, or theft; and serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic, automated, or computerized system [section 3(2)].

The inclusion of these offences in a counter-terrorism law, given the empirical experience of the past, is no less than an invitation to abuse of the system for collateral purposes, with the distinct prospect of danger to cherished democratic freedoms in such vital areas as communication and assembly. This is especially so, because the types of intention envisaged subsume so vague a purpose as “compelling the government of Sri Lanka or any other government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act” [section 3(1) (c)]. The peril is obvious to entirely legitimate forms of protest and agitation. It must be remembered that the penalty applicable is rigorous imprisonment extending up to 20 years and a fine not exceeding 20 million rupees [section 4(b)].

This clearly threatening feature is aggravated by other characteristics of the draft Bill. Several are worthy of note.

(i) Ancillary offences are framed in such broad terms as to inject a deterrent effect in respect of exercise of individual and group rights enshrined by the Constitution. Section 8(1), according to its marginal note, purports to deal with acts “associated with terrorism”, a vague and catch-all phrase. The text of this provision imposes liability on a person who is “concerned in” the commission of a terrorist offence. “Encouragement of Terrorism”, the title of section 9, is manifestly overbroad. Its ambit, encompassing all forms of “indirect encouragement”, would sweep within its purview, for instance, a large swath of the activity associated with the Aragalaya in 2022, which brought about a change of government.

There is unmistakable exposure for all forms of social activism. Section 10, entitled “Dissemination of Terrorist Publications”, goes so far as to bring within the net of liability for terrorism any person who “provides a service to others that enables them to obtain, read, listen to, or look at a terrorist publication or to acquire it”. The whole range of mainstream and social media is indisputably in jeopardy.

(ii) There are other obnoxious aspects, as well. The draft law makes generous use of the idea of “recklessness”, as in the context of publication of statements and uttering of words (section 9), and in the dissemination of publications (section 10). This is a state of mind alternative to intention; but the concept of “recklessness” is operative within very narrow confines in criminal jurisprudence. This is yet another lever for expansion of liability beyond the class of terrorist offences, properly so designated.

(iii) A feature of the proposed law, open to even more cogent objection, is the extension of this draconian form of liability, carrying condign punishment, to mere omissions. This is the effect of section 15, which makes failure to provide information a terrorist offence. The trend in the modern criminal law is markedly hostile to widening the boundaries of liability to situations in which the accused has only refrained from commission of an act. One of my own mentors, Professor Glanville Williams of Cambridge University, described by Professor Sir Rupert Cross, at the time Vinerian Professor in the University of Oxford, as the greatest criminal lawyer in the United Kingdom since Sir Fitzjames Stephen, has consistently opposed, in principle, the attribution of criminal liability, let alone liability for terrorist offences, to mere omissions. In conjunction with all the other instruments embedded in the draft, this expedient places in the hands of a politically motivated Executive a ready means for indiscriminate application of terrorist sanctions, to the detriment of enjoyment of rights taken for granted in a democratic society.

(iv) Section 3(4), which purports to confer a measure of protection on such activity as protests, advocacy of dissent, or engagement in strikes, by a provision that such activity, by itself, is not to be regarded as a sufficient basis for inference of terrorist intent, has an illusory character. While engendering a sense of comfort, its applicability is negated by parallel provisions which enable imposition of liability, for example, on the ground of alleged intent to bring compulsive pressure to bear on the State [section 3(1)(c)]. Uncertainty created by the conflict between these provisions places at unacceptable risk the ethos of democratic safeguards.

III. Overreach of the Executive Arm for Arrest and Detention

Broadening of categories of terrorist offences beyond legitimate limits presages an imminent danger. This takes the form of authority conferred on the Executive, represented by such officials as the armed forces, the police, and coast guard personnel, to resort to action which erodes the rudiments of liability. The wider the ambit of terrorist offences, the ampler is the power available to these officials to invade the substance of freedom by action to enter the homes of citizens, interrogate persons, seize documents, carry out stop and search operations on public highways, and engage in other forms of harassment. The current draft has no hesitation in conferring these powers in the fullest measure.

(i) Detention Orders

This is one of the features of the PTA of 1979, which attracted trenchant criticism for more than four decades. In terms of section 9(1) of that Act, the Minister of Defence was invested with power to issue detention orders for a maximum period of three months in the first instance, capable of extension for periods not exceeding three months at a time, subject to an aggregate period of detention not exceeding 18 months. Significantly, corresponding provision is contained in the current draft which empowers the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence to issue detention orders [section 29(2)] at the behest of the Inspector General of Police or a Deputy Inspector General of Police authorized by the IGP [section 29(1)].

The only difference is with regard to the period of detention. According to the new draft, the detention order cannot be extended for a period in excess of two months at a time, and the aggregate period is a maximum of one year. Subject to this marginal variation, the perils of the instrument of a detention order continue, unabated.

What is especially disquieting are the grounds specified in the draft for issuance of a detention order. There are four grounds spelt out. Among these is “to facilitate the conduct of the investigation in respect of the suspect” [section 3(a)]. This is wide enough to permit the most flagrant abuse. A provision, so flexibly phrased, allows detention without judicial review. Due process, required by the regular criminal justice system, is supplanted by a regime antithetical at its core to the fundamentals of the Rule of Law.

Our country has had a distressing record of torture and extrajudicial executions in custodial settings. The recurring feature is that these atrocities have typically taken place in non-judicial custody. In the face of this reality and in cynical disregard of sustained protests against this obvious avenue of abuse, the present draft complacently leaves wide open this convenient window. This is done by section 30(1) which accords official sanction to “approved places of detention”. The accumulated harrowing experience of the past has totally escaped attention.

Despite largely cosmetic concessions, the victims of detention orders within the framework of the proposed legislation, no less than under previous statutory regimes, remain substantially at the mercy of the Executive.

The exhortation in section 36 that “Every investigation shall be completed without unnecessary delay” amounts to no more than a pious aspiration, in the absence of a mandatory maximum period stipulated for investigations. Moreover, even when the investigation, potentially open-ended, has been completed and a report submitted to the Magistrate, the Magistrate’s power to discharge the suspect is rigidly curtailed. This is because a judicial order for discharge is possible in terms of section 36(3) only when an allegation against the suspect is not disclosed on the face of the report. There is telling irony in this situation.

The loophole is one through which the Executive is able to drive a coach and six with the greatest ease. Practical experience demonstrates conclusively that, in situations indicative of the most grotesque abuse in the past, the courts were confronted not with the total absence of an allegation, but rather with a clumsy, trumped-up allegation defying credibility. In this, the typical case, the proposed legislation chooses to leave the Magistrate with no jurisdiction to grant urgently needed relief.

The most hazardous provision of all is one which enables a suspect, already in judicial custody, to be transferred to police custody in pursuance of a detention order issued by the Defence Secretary. It is this power, fraught with dire consequences, that the new draft, in section 39(1), seeks to confer. This power can be invoked on the disingenuous pretext that the suspect, prior to being arrested, had committed an offence of which the officer in charge of the relevant police station was unaware. While the desirable direction of movement is obviously from police to judicial custody, movement in the opposite direction is the strange result of this provision. Although interposition of a High Court Judge’s authority is envisaged, the exigencies of a security situation, urged with emphasis by the Executive, may well be difficult to resist in practice.

IV. Other Oppressive Interventions

(a) Restriction Orders

It is quite remarkable that other instruments of oppression which have attracted strenuous condemnation during the entire operation of the PTA, continue substantially intact.

Restriction orders offer an illustrative example. Any police officer of the rank of Deputy Inspector General of Police or above is given authority to make application to a Magistrate’s Court for a restriction order (section 64). The only contrast with the PTA is that, in terms of that regime, the Minister was empowered to make the order directly. In subsequent attempts at reform, this was clearly acknowledged as unacceptable, and in the amending legislation proposed but not enacted in September 2023, the initiative was that of the President and it was the High Court that had jurisdiction to issue the order.In comparison with this, the current proposal is regressive, in that the application is to be made by a police officer, (clearly at the behest of the Executive), and jurisdiction to issue the order is vested in a lower court.

In yet another respect, the present proposal is less satisfactory than the innovation proposed in 2023, in that desirable safeguards embedded in the latter, such as that the order sought should be “necessary” or “proportionate” [section 80(4)], are omitted from the present proposal. In this sense, the current draft is not merely stagnant but regressive, by abjuring salutary approaches to reform.

Restriction orders, without doubt, infringe basic rights corrosively. Their awesome scope contravenes core rights as to communication, association, employment, and travel [section 64(3)]. These erosions remain untouched as to intensity and range, except in respect of duration.While the PTA provided that a restriction order was to be in force for a period not exceeding 3 months, subject to further extensions of 3 months at a time, the maximum aggregate of such extensions being 18 months, the sole concession made by the present proposal is that the validity of a restriction order is limited to 1 month, and the aggregate period cannot exceed 6 months [section 64(9)].

(b) Proscription Orders

In this regard as well, the present proposal takes a step in the wrong direction. Proscription orders are a means by which the President exercises overarching power, simply by notification in the Gazette, to declare organizations illegal, with the consequence of preventing recruitment, meetings, and other activities, transactions in bank accounts, lobbying and canvassing, and publication of material (section 63). The period of application of a proscription order has an arbitrary and capricious quality: it is entirely at the discretion of the President and remains valid until rescinded [section 63(6)].

It is especially noteworthy that the legislative regime at present in force, the PTA, contains no provision whatever for the issuance of proscription orders. This purpose could be accomplished only by having recourse to regulations made under section 27(1) of the Act. Incorporation of this power in the substance of the principal Act itself was proposed in the draft legislation of 2023, which could not be enacted because of vehement resistance. The current proposal, curiously enough, sanctifies as part of the substantive Act, a dangerously fraught procedure which can, as of now, be resorted to only through subordinate legislation. The present draft, then, operates as a travesty rather than a palliative by pushing the law backwards. This hardly amounts to delivery on a promise that underpinned the year-long process which culminated in publication of the current proposal.

(c) Declarations Designating Prohibited Places

The bizarre reality, here again, is that the present proposal, far from expunging excrescences from the current law, actually adds further objectionable provisions which do not exist in the body of terrorist legislation today.

The much-maligned PTA does not include a provision empowering the Executive to declare places as “prohibited places”. This had to be done, if at all, under the aegis of legislation dealing with entirely different subject matter, for example, section 2 of the Official Secrets Act, No. 32 of 1955. Contrary to the professed objective, the new proposal, for the first time, introduces into terrorist legislation the conferment of power on the Defence Secretary to designate “prohibited places”.

The consequences are far-reaching, indeed: entry into a designated place, the taking of photographs and video recordings, and the making of drawings or sketches are all criminalized by the infliction of imprisonment for up to 3 years or a fine not exceeding 3 million rupees [section 66(8)]. This has a particularly chilling effect on journalists and media personnel; and it is the bequest of legislation professedly aspiring to enhance the contours of freedom.

V. Deprivation of Liberty by Insidious Pressure

One of the few positive elements of the new proposal is the deletion of provisions in the PTA dealing with the admissibility of confessions made to a police officer above the rank of an Assistant Superintendent [section 16(1) of the PTA]. Unfortunately, however, this benefit is largely detracted from by other provisions which constitute an onslaught on values intrinsic to the Rule of Law. Pre-eminent among these is the presumption of innocence and the postulate precluding denial of freedom except in full compliance with due process, both substantively and procedurally.

These sacrosanct values receive short shrift in the proposed law, which gives the Attorney-General overwhelming coercive powers in respect of deferment of criminal proceedings on the basis of an iniquitous quid pro quo. The Attorney-General is invested with authority to defer the institution of criminal proceedings for as long a period as 20 years on the footing of a “prior consensual agreement” between the Attorney-General and the suspect, subject to sanction by the High Court [section 56(1)].

It is entirely unrealistic to impute to this “agreement” any element of spontaneity or independent volition. The suspect finds himself under virtually irresistible pressure to acquiesce in any condition proposed, in order to obtain release from the stress and turmoil of a criminal trial potentially entailing the gravest penalties. The situation becomes wholly untenable when the condition takes the form of submission to “a specified programme of rehabilitation”. This is a euphemism for de facto incarceration under thinly-veiled duress without the interposition of a fair trial before a court of law.

VI. Conclusion

Far from making any contribution of value to restoration of balance between security and freedom, the proposed draft has the effect of reversing some of the recent gains of law reform in this field without offering anything significant by way of redeeming features. This is a statutory misadventure which can reflect no credit on the laws of our country.

By Professor G. L. Peiris ✍️

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D. (Sri Lanka);

Former Minister of Justice, Constitutional Affairs and National Integration;

Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo.

Opinion

Faith, religion, and us in 2026

I thought of compiling this after reading a leading editorial: “We live in a world of lies, damned lies, and AI hallucinations. A US publication calculated that Donald Trump told 30,573 lies in his first term as President. A lie, they say, travels halfway around the world before the truth gets its boots on. Today, truth might as well stay in bed” (BMJ Editorial, 20th December 2025). Lies—in the form of fake news, videos, messages, and even telephone calls—try to lure us into traps that can cost us our assets, belongings, or even cash, often leaving the perpetrators untraceable. Faiths and religions face similar threats.

Faiths and religions contribute to social harmony by providing shared values and moral frameworks—such as compassion, forgiveness, and justice—and by fostering community through worship, rituals, and charitable work. These practices encourage belonging, trust, and cooperation. Religious leaders often mediate conflicts, promoting dialogue and stability, while diverse traditions enrich culture and cultivate tolerance.

However, these same frameworks are increasingly misused to distort doctrine, promote hatred, incite violence, and even justify killings, sometimes leading to wars of utter destruction. Our moral obligation is to safeguard our faiths—including respecting those who do not follow any faith, as that itself reflects a belief system—by understanding the threats we face, recognising them, and keeping a safe distance, while primarily focusing on deepening our own faith or religion through personal experience.

What Is Faith?

Faith is more than belief—it is trust, confidence, and commitment. Often associated with religion, faith can mean belief in God or in spiritual teachings without proof. It also applies to trust in a person, dedication to an idea, or loyalty to a cause.

=In Islam, faith (Iman) includes belief in God, angels, holy books, messengers, the Last Day, and divine decree.

=In Christianity, faith is confidence in what is hoped for and assurance in what is unseen.

=Outside religion, faith can mean unwavering trust in someone or something, or a commitment to principles, as seen in expressions such as “keep faith” or “break faith.”

Understanding Religion

Religion is a system of beliefs, practices, and ethics that connects people to the spiritual or supernatural. It offers meaning, answers life’s big questions, and guides conduct. Common elements include moral codes, rituals, sacred texts, holy places, and community traditions.

Religions may focus on gods, spiritual concepts, or ethical teachings. Practices such as prayer, meditation, or moral observance help followers navigate life, build community, and explore the mysteries of existence. Major world religions include Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism, while countless indigenous and alternative spiritual practices thrive worldwide.

When Faith Is Exploited

Sadly, faith and religion can be misused. Individuals seeking personal gain may manipulate trust and devotion. These include:

=Charlatans: claim false spiritual knowledge.

=Con artistes: promise spiritual rewards in exchange for money.

=Opportunists: exploit religious beliefs for financial, social, or political gain.

=False prophets and spiritual abusers: manipulate followers under the guise of authority.

In everyday terms, they are hypocrites, scammers, or manipulators. Protecting oneself requires discernment and relying on personal experience rather than blind trust.

Safeguarding Our Faith

Maintaining genuine faith can feel like navigating an obstacle course. The wisest approach is to keep faith personal, practise it sincerely, and follow a spiritual path informed by your own experiences. True faith thrives in authenticity, reflection, and mindful practice. In a world of easy exploitation, faith is strongest when quietly lived and genuinely felt.

by Chula Goonasekera ✍️

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoPharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoCurran, bowlers lead Desert Vipers to maiden ILT20 title