Features

Evolution from AM radio to Digital TV broadcasting

Parliamentary Acts on Broadcasting and Telecommunications

by DR JANAKA RATNASIRI

The Cabinet of Ministers (COM) has recently decided to update the Parliamentary Acts on Broadcasting, Rupavahini and Telecommunications and introduce a Bill on establishing a Broadcasting Regulatory Commission. Since, all these are interlinked, it is necessary to take a holistic view of them, taking into consideration new developments such as digital broadcasting. Before that, it would be pertinent to consider the historical development of these services.

USE OF ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES FOR COMMUNICATION

The Electromagnetic (EM) Spectrum comprising EM waves, extends from high energetic gamma rays, X-Rays and ultra-violet rays on one extreme to low energetic visible, infra-red, microwaves and radio waves on the other extreme. All these are generated naturally by the sun, but almost all of the high energetic radiations get absorbed in the upper atmosphere and only the low energetic radiations are received at ground level. They are also generated by man for various applications like X-Rays, microwaves and radio waves. Out of these, microwaves and radio waves are used for telecommunication purposes, commonly referred to as wireless communication.

EM waves comprise oscillating electric and magnetic fields generated when electrons oscillate either in a plasma or in a conductor. These two fields have their directions perpendicular to each other. They cause radiation of energy in the form of a wave travelling in a direction perpendicular to directions of both electric and magnetic fields. They are characterized by the fact their frequency in Hertz (Hz) and wavelength in metres (m) are inversely proportional to each other with their product equal to the speed of light in vacuum which is 299.8 million m/s. It was James Maxwell who presented the theory of EM waves around 1865 while Gustav Hertz demonstrated their existence in 1887 which earned him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1925.

Hertz’s discovery led to Guglielmo Marconi demonstrating in 1901 that high frequency (HF) waves could be used to send signals across the Atlantic. This caused the birth of the telecommunication industry, for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1909. Though HF radio waves were used for long distance communication, the mechanism of their propagation over several thousands of kilo-metres was not understood at that time. Theories of propagation available at that time considered only ground wave propagation which has limited range and line-of-sight propagation which also has limited range along the Earth’s surface. Hence, coverage across the Atlantic was a puzzle at that time.

It was left to Edward Appleton to explain this phenomenon when he discovered in 1927 the existence of the ionosphere, a layer of charged particles lying about 100 km above the ground, which bounces off these radio waves back to the Earth when they are incident on it. Appleton received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1947 for this discovery. It was soon found that radio waves could be used not only for telecommunication purposes, but also for providing voice broadcasting services, known as radio, both within and across countries. HF radio waves remained the only means of long-distance telecommunication as well as broadcasting until the mid-sixties when satellite-based communication took over which came into being, thanks to the vision of Sir Arthur C. Clarke announced in 1945 in the Wireless World Magazine.

DEVELOPMENT OF RADIO BROADCASTING SERVICES

Public broadcasting in Sri Lanka commenced in 1925 as Radio Colombo with limited coverage around the city using only MF transmissions. It expanded to a wider coverage about 10 years later and continued till 1949 when its identity was changed to Radio Ceylon. The services were also extended to provide short wave transmissions to provide island-wide coverage though the service was of poor quality due to inherent ionospheric disturbances. Radio Ceylon had one advertisement-free service in each language for many years and added separate commercial services later. Though Radio Ceylon functioned for many years as a semi-government organization under different Ministries from time to time, it lacked a proper legal framework.

To remedy this situation, the Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) Act No. 37 of 1966 was passed in Parliament and the CBC was established in 1967 which brought Radio Ceylon to function under it. The Act was amended thrice, to make SLBC both a regulator and a service provider. One amendment was to change its name to Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC). Another was for the issue of licenses by the Minister to other persons for the establishment of private broadcasting stations. The amended Act also required an owner of a radio receiver to obtain a licence annually through the Post Office. The Act also requires any person selling, assembling, repairing or renting radio equipment to obtain an annual licence from SLBC to perform that function. Thus, the SLBC performed a dual role of being a service provider and a regulator.

The evolution of radio technology from vacuum tube-based home radio receivers available up to sixties to transistor and integrated circuit based portable radio receivers currently available in the market made it impossible to implement the licensing provision. Hence, this requirement was abolished subsequently, but the provision still remains in the Act. Today, every motor car has a built-in radio receiver and every smart mobile telephone has a built-in radio receiver. Hence, there is a need to amend the SLBC Act to remove this outdated provision.

From the inception, radio broadcasting in Sri Lanka was confined to transmission of amplitude modulated (AM) signals which had limited band-width causing high frequencies in the audio signal getting clipped. This affected the quality of musical programmes severely. These transmissions were in the medium frequency (MF) (or medium waves) for short range coverage and high frequencies (HF) (or short waves) for covering the entire island. The short waves reach the listener after getting reflected from the ionosphere which is a dynamical entity and hence the signals received were not steady and of poor quality. In the sixties, SLBC built several MF transmitters in outstations enabling outstation listeners to have the benefit of receiving quality programmes free of ionospheric disturbances.

In the seventies, the SLBC commenced limited transmissions of signals with frequency modulation (FM) on the very high frequency (VHF) band. These transmissions have higher bandwidth and hence the audio programmes received are of high quality, and also require much less power to transmit. They are also not affected by atmospheric or ionospheric disturbances. The only problem is that their coverage is limited to line-of-sight range. Later the service was extended to provide an island-wide coverage through the installation of several transmitters, most of which are installed on hill-tops to extend the coverage.

Up to the end of the 1980s, the SLBC had the monopoly of operating radio services, but in the nineties and twenties, several private parties, exceeding 20, were issued licences to operate radio services in the FM band. Each service was given two frequencies enabling them to cover the entire island. Most of them, except a few who offered religious programmes, came up with only low quality musical programmes providing requests on payment devoting a major share of air time on advertisements which brought the revenue for their survival. The lack of a suitable mechanism to monitor the quality and content of the programmes aired is a serious shortcoming in the present system.

DEVELOPMENT OF TELEVISION BROADCASTING SERVICES

Television (TV) service was introduced to Sri Lanka in 1979 when a private party launched a service voluntarily. Later, it was taken over by the Government. At that time, there was no policy or regulations on establishing TV services in the country. The Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC) Act, No. 06 of 1982 was passed under which the SLRC was established with functions of the Corporation to carry on a television broadcasting service within Sri Lanka and to promote and develop that service and maintain high standards in programming in the public interest. The Rupavahini TV service was launched by SLRC using a package gifted by Japan, with the main antenna erected on Mt. Pidurutalagala.

The Act is required to register persons engaged in the production of television programmes for broadcasting; to register persons who carry on the business of importing, selling, manufacturing or assembling television receiving sets; to exercise supervision and control over television programmes broadcast by the Corporation; and to exercise supervision and control over foreign and other television crews, producing television programmes for export, among others.

Thus, the SLRC also has a dual role similar to that of SLBC, of being a service provider and a regulator. However, it lacked the powers to implement the provisions to exercise supervision and control on other TV services as described in the last two items given in the previous section. The SLRC Act has provision to issue licences to qualified parties to establish and operate TV stations. Accordingly, 54 private television licenses have been issued licences so far, whereas only 28 telecasting licensees are in operation at present (Cabinet Decision of 04.03.2020).

The Cabinet of Ministers (COM) at its meeting held on 04.01.2021 has decided to amend the SLRC Act to provide for the expansion of its Board of Directors to empower it to implement decisions taken with a view to face the competitive scenario prevailing in the field. No further amendments have been identified even though the Act is totally out of date considering the developments in the field during the last 19 years. There is a need to bring SLRC under the proposed Broadcasting Regulatory Commission to remove the regulatory functions from it and also to remove the provision to possess a licence by a user.

ESTABLISHING A TELECOMMUNICATION REGULATORY COMMISSION

In early days, the telecommunication services were provided by the Posts and Telecommunication Department, which was later bifurcated into two departments. The government passed the Sri Lanka Telecommunication (SLT) Act No. 25 in 1991 which provided for the establishment of the Sri Lanka Telecommunication Authority (SLTA) which took over the functions of the Telecommunication Department. Among the objectives of the SLTA are to ensure the conservation and proper utilization of the radio frequency spectrum by operators and other organizations and individuals who need to use radio frequencies and to make and enforce compliance with rules to minimize electro-magnetic disturbances produced by electrical apparatus and all unauthorized radio frequency emissions, among others.

The SLT Act was amended by Act No. 27 of 1996 whereby the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL) was established in place of SLTA. The amended Act made provisions for receiving complaints from the public and holding public hearings on them and retained all the functions assigned to the SLTA. Its regulatory functions were limited to telecommunication service providers and did not cover the broadcasting of radio or TV services, other than assigning frequencies for them. This is unlike in India where the Telecommunication Authority covered regulation of Broadcasting of Radio and TV services both in terms of technical aspects and quality of programmes.

PROPOSAL FOR ESTABLISHING A BROADCASTING REGULATORY COMMISSION

The COM at its meeting held on 04.03.2020 having considered the necessity of having a separate institution to regulate the activities of the broadcasting and telecasting media based on a Committee recommendation approved a draft for setting up a ”Broadcasting Regulatory Commission” (BRC), and decided to explore the possibility of amending the SLTRC Act, to enable it to perform the task of the process of issuing Broadcasting and Telecasting Licenses, which were hitherto issued by the SLBC and SLRC, respectively. The objective is to remove the regulatory functions from these two organizations and transfer them to the new Commission.

As early as 1997, a Broadcasting Authority Bill was presented to the Parliament for the same purpose but it was held unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court because it did not give adequate independence to the Authority. Thereafter, a Select Committee of Parliament with representation of all parties was appointed to consider the problem and met on multiple occasions but the matter was left in abeyance. Now, it has resurfaced under a new heading – Broadcasting Regulatory Commission. However, its contents are not available in the public domain, not even in the Govt Printer’s website.

Unlike in early days when broadcasted programmes whether radio or TV were available only as free-to-air services, today with advances in technology, particularly TV programmes, are brought to residences using either physical cables or UHF links or satellite links or through the internet. Since free-to-air services are not available island-wide with acceptable quality, people opt for these services upon payment of a monthly fee. But some satellite links do not provide a satisfactory service when it rains, though the service provider claims it provides tomorrow’s technology today.

There is also an urgent need to exercise some control on the utilizing of TV medium for advertising purposes. While there is a positive aspect whereby a viewer receives information on a new product or service, the repetitive display of the same commercial of well-known consumer products is nothing but an annoyance. The writer believes that during prime time, between almost 50% of air time is devoted for commercials and promotional clips. This is in contrast to India where only 10 min of commercials are allowed for every 60 min of air-time. Hence, there is a need to have a regulatory body to ensure that satisfactory services are provided to subscribers, both in terms of the quality of signal received and the quality of programmes aired.

A notable characteristic of Sri Lanka’s TV service providers is that they seem to be very prudish when it comes to airing cinematographic material intended for adult audience, but of high quality which have received accolades at international events. The operator loses no time in blanking even a momentary kissing scene in them. The proposed BRC could lay some guidelines on presenting quality adult programmes which have already been cleared by the National Censor Board enabling the adult audience to enjoy them without subjecting them to additional censorship by TV operators. Perhaps, such programmes could be limited for airing during late hours of the day when children have gone to bed.

TRANSITION FROM ANALOG TV TO DIGITAL TV SYSTEMS

There is a global trend to switch from analogue to digital system for television broadcasting as it offers many advantages among which are better spectrum utilization, higher picture and sound quality, accessibility via mobile devices and new business opportunities. Under the sponsorship of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a Roadmap for Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Television Broadcasting (DTTB) in Sri Lanka was jointly developed in 2012 by a team of ITU experts from Korea and the National Roadmap Team (NRT) chaired by TRCSL.

Digital TV transmission, though will provide a high-quality service, will result in added expenditure both for the service provider and the viewer. In order to reduce the financial burden for the service provider, NRT proposed to establish a set of 8 common digital transmitters at sites already being used for TV transmission, for sharing by all service providers. They are expected to provide initially simultaneous transmissions both on analog and digital systems, so that a viewer will be able to receive programmes uninterruptedly when switching from analog to digital system.

As a follow up to the above proposal, the GoSL assigned a “Feasibility Study on Digital Terrestrial Television Broadcasting Network Project” in 2014, to Japan International Cooperation Agency. (). This study recommended setting up of 16 digital transmitters to be managed by a separate body, with the principal tower at Lotus Tower in Colombo. Individual TV services are expected to send their high definition programmes to Lotus Tower by microwave or other links who will in turn broadcast them from the common set of transmitters. By this means, all the TV channels will be received at the same signal strength anywhere in the country.

It was proposed to establish a body to be known as “Digital Broadcast Network Operator” (DBNO) to organize, manage and administer the new system. DBNO is expected to operate and maintain the entire system with the revenue from the operation fees collected from broadcasting stations. The transition to DTTB will result in incurring heavy expenditure by both DBNO and individual service providers, including installing new antenna systems, purchasing digital studio equipment such as cameras, animators, programme mixers etc. all of which could run into Billions of Rupees.

In addition, viewers will have to purchase either set-top-boxes for use with analog receivers or new digital receivers. It may be recalled that with the new development in TV technology, the earlier Cathode-Ray-Tube (CRT) type TV receivers were replaced by slim type LCD/LED TV receivers during the last couple of years. Today, CRT receivers are no longer available in the market. Hence, changing receivers will not be an issue for our viewers, as long as it carries benefits.

In the event the Government decides to adopt the DTTB system, it will be necessary to introduce new laws and regulations to regulate the new DTTB industry, and considering the complexities involved, it is best if a total new Parliament Act is passed, with appropriate amendments to both the SLRC Act and SLT Act. The COM has already decided to amend both these Acts as mentioned above. It is therefore appropriate if the Committee to be appointed for this purpose also be given the mandate to study the desirability of introducing DTTB in Sri Lanka considering costs and benefits as well as viewer preferences and service provider views.

Though the GoSL entered into an agreement with JICA to pursue the matter in 2014, with the change of Government in 2015, the matter was left in abeyance. Under the new Government, the matter is being considered, but no decision has been made as to when it will be implemented and which DTTB standard to adopt, as learned by the writer when he started writing this piece. However, according to a news item telecast in the evening of 19.01.2021, the Japanese Government has offered assistance to Sri Lanka to switch over to DTTB as described in JICA Report issued in 2014, and the Cabinet Spokesman Minister said that Sri Lanka would soon adopt the new system.

CONCLUSION

Sri Lanka will be completing 100 years of public radio broadcasting in four years hence, and has come a long way going through various stages of development. Initially, there were no separate laws to regulate the industry, and the state-owned service provider used to do that function. This position remains unchanged to date and only recently that the Government has considered establishing separate organizations to provide regulatory function. Only the amendment of SLRC Act and SLT Act are being considered along with setting up a new Commission for regulating broadcasting of radio and television services. Hence, there is a need to consider amending these two Acts together with amending the SLBC Act.

With the proposed introduction of digital television transmission in Sri Lanka as reported by the Cabinet spokesman, the Writer suggests that the amendment of the above three Acts should be taken up along with formulating a new Act to cover Digital Transmission Broadcasting since all four are interlinked, before the actual transition takes place. It is hoped that with the introduction of digital TV transmissions the quality of programme content will also improve concurrently.

Features

Indian Ocean Security: Strategies for Sri Lanka

During a recent panel discussion titled “Security Environment in the Indo-Pacific and Sri Lankan Diplomacy”, organised by the Embassy of Japan in collaboration with Dr. George I. H. Cooke, Senior Lecturer and initiator of the Awarelogue Initiative, the keynote address was delivered by Prof Ken Jimbo of Kelo University, Japan (Ceylon Today, February 15, 2026).

The report on the above states: “Prof. Jimbo discussed the evolving role of the Indo-Pacific and the emergence of its latest strategic outlook among shifting dynamics. He highlighted how changing geopolitical realities are reshaping the region’s security architecture and influencing diplomatic priorities”.

“He also addressed Sri Lanka’s position within this evolving framework, emphasising that non-alignment today does not mean isolation, but rather, diversified engagement. Such an approach, he noted, requires the careful and strategic management of dependencies to preserve national autonomy while maintaining strategic international partnerships” (Ibid).

Despite the fact that Non-Alignment and Neutrality, which incidentally is Sri Lanka’s current Foreign Policy, are often used interchangeably, both do not mean isolation. Instead, as the report states, it means multi-engagement. Therefore, as Prof. Jimbo states, it is imperative that Sri Lanka manages its relationships strategically if it is to retain its strategic autonomy and preserve its security. In this regard the Policy of Neutrality offers Rule Based obligations for Sri Lanka to observe, and protection from the Community of Nations to respect the territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, unlike Non-Alignment. The Policy of Neutrality served Sri Lanka well, when it declared to stay Neutral on the recent security breakdown between India and Pakistan.

Also participating in the panel discussion was Prof. Terney Pradeep Kumara – Director General of Coast Conservation and Coastal Resources Management, Ministry of Environment and Professor of Oceanography in the University of Ruhuna.

He stated: “In Sri Lanka’s case before speaking of superpower dynamics in the Indo-Pacific, the country must first establish its own identity within the Indian Ocean region given its strategically significant location”.

“He underlined the importance of developing the ‘Sea of Lanka concept’ which extends from the country’s coastline to its 200nauticalmile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Without firmly establishing this concept, it would be difficult to meaningfully engage with the broader Indian Ocean region”.

“He further stated that the Indian Ocean should be regarded as a zone of peace. From a defence perspective, Sri Lanka must remain neutral. However, from a scientific and resource perspective, the country must remain active given its location and the resources available in its maritime domain” (Ibid).

Perhaps influenced by his academic background, he goes on to state:” In that context Sri Lanka can work with countries in the Indian Ocean region and globally, including India, China, Australia and South Africa. The country must remain open to such cooperation” (Ibid).

Such a recommendation reflects a poor assessment of reality relating to current major power rivalry. This rivalry was addressed by me in an article titled “US – CHINA Rivalry: Maintaining Sri Lanka’s autonomy” ( 12.19. 2025) which stated: “However, there is a strong possibility for the US–China Rivalry to manifest itself engulfing India as well regarding resources in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While China has already made attempts to conduct research activities in and around Sri Lanka, objections raised by India have caused Sri Lanka to adopt measures to curtail Chinese activities presumably for the present. The report that the US and India are interested in conducting hydrographic surveys is bound to revive Chinese interests. In the light of such developments it is best that Sri Lanka conveys well in advance that its Policy of Neutrality requires Sri Lanka to prevent Exploration or Exploitation within its Exclusive Economic Zone under the principle of the Inviolability of territory by any country” ( https://island.lk/us- china-rivalry-maintaining-sri-lankas-autonomy/). Unless such measures are adopted, Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone would end up becoming the theater for major power rivalry, with negative consequences outweighing possible economic gains.

The most startling feature in the recommendation is the exclusion of the USA from the list of countries with which to cooperate, notwithstanding the Independence Day message by the US Secretary of State which stated: “… our countries have developed a strong and mutually beneficial partnership built on the cornerstone of our people-to-people ties and shared democratic values. In the year ahead, we look forward to increasing trade and investment between our countries and strengthening our security cooperation to advance stability and prosperity throughout the Indo-Pacific region (NEWS, U.S. & Sri Lanka)

Such exclusions would inevitably result in the US imposing drastic tariffs to cripple Sri Lanka’s economy. Furthermore, the inclusion of India and China in the list of countries with whom Sri Lanka is to cooperate, ignores the objections raised by India about the presence of Chinese research vessels in Sri Lankan waters to the point that Sri Lanka was compelled to impose a moratorium on all such vessels.

CONCLUSION

During a panel discussion titled “Security Environment in the Indo-Pacific and Sri Lankan Diplomacy” supported by the Embassy of Japan, Prof. Ken Jimbo of Keio University, Japan emphasized that “… non-alignment today does not mean isolation”. Such an approach, he noted, requires the careful and strategic management of dependencies to preserve national autonomy while maintaining strategic international partnerships”. Perhaps Prof. Jimbo was not aware or made aware that Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy is Neutral; a fact declared by successive Governments since 2019 and practiced by the current Government in the position taken in respect of the recent hostilities between India and Pakistan.

Although both Non-Alignment and Neutrality are often mistakenly used interchangeably, they both do NOT mean isolation. The difference is that Non-Alignment is NOT a Policy but only a Strategy, similar to Balancing, adopted by decolonized countries in the context of a by-polar world, while Neutrality is an Internationally recognised Rule Based Policy, with obligations to be observed by Neutral States and by the Community of Nations. However, Neutrality in today’s context of geopolitical rivalries resulting from the fluidity of changing dynamics offers greater protection in respect of security because it is Rule Based and strengthened by “the UN adoption of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of peace”, with the freedom to exercise its autonomy and engage with States in pursuit of its National Interests.

Apart from the positive comments “that the Indian Ocean should be regarded as a Zone of Peace” and that “from a defence perspective, Sri Lanka must remain neutral”, the second panelist, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Ruhuna, Terney Pradeep Kumara, also advocated that “from a Scientific and resource perspective (in the Exclusive Economic Zone) the country must remain active, given its location and the resources available in its maritime domain”. He went further and identified that Sri Lanka can work with countries such as India, China, Australia and South Africa.

For Sri Lanka to work together with India and China who already are geopolitical rivals made evident by the fact that India has already objected to the presence of China in the “Sea of Lanka”, questions the practicality of the suggestion. Furthermore, the fact that Prof. Kumara has excluded the US, notwithstanding the US Secretary of State’s expectations cited above, reflects unawareness of the geopolitical landscape in which the US, India and China are all actively known to search for minerals. In such a context, Sri Lanka should accept its limitations in respect of its lack of Diplomatic sophistication to “work with” such superpower rivals who are known to adopt unprecedented measures such as tariffs, if Sri Lanka is to avoid the fate of Milos during the Peloponnesian Wars.

Under the circumstances, it is in Sri Lanka’s best interest to lay aside its economic gains for security, and live by its proclaimed principles and policies of Neutrality and the concept of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace by not permitting its EEC to be Explored and/or Exploited by anyone in its “maritime domain”. Since Sri Lanka is already blessed with minerals on land that is awaiting exploitation, participating in the extraction of minerals at the expense of security is not only imprudent but also an environmental contribution given the fact that the Sea and its resources is the Planet’s Last Frontier.

by Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

Protecting the ocean before it’s too late: What Sri Lankans think about deep seabed mining

Far beneath the waters surrounding Sri Lanka lies a largely unseen frontier, a deep seabed that may contain cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements essential to modern technologies, from smartphones to electric vehicles. Around the world, governments and corporations are accelerating efforts to tap these minerals, presenting deep-sea mining as the next chapter of the global “blue economy.”

For an island nation whose ocean territory far exceeds its landmass, the question is no longer abstract. Sri Lanka has already demonstrated its commitment to ocean governance by ratifying the United Nations High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement) in September 2025, becoming one of the early countries to help trigger its entry into force. The treaty strengthens biodiversity conservation beyond national jurisdiction and promotes fair access to marine genetic resources.

Yet as interest grows in seabed minerals, a critical debate is emerging: Can Sri Lanka pursue deep-sea mining ambitions without compromising marine ecosystems, fisheries and long-term sustainability?

Speaking to The Island, Prof. Lahiru Udayanga, Dr. Menuka Udugama and Ms. Nethini Ganepola of the Department of Agribusiness Management, Faculty of Agriculture & Plantation Management, together with Sudarsha De Silva, Co-founder of EarthLanka Youth Network and Sri Lanka Hub Leader for the Sustainable Ocean Alliance, shared findings from their newly published research examining how Sri Lankans perceive deep-sea mineral extraction.

The study, published in the journal Sustainability and presented at the International Symposium on Disaster Resilience and Sustainable Development in Thailand, offers rare empirical insight into public attitudes toward deep-sea mining in Sri Lanka.

Limited Public Inclusion

“Our study shows that public inclusion in decision-making around deep-sea mining remains quite limited,” Ms. Nethini Ganepola told The Island. “Nearly three-quarters of respondents said the issue is rarely covered in the media or discussed in public forums. Many feel that decisions about marine resources are made mainly at higher political or institutional levels without adequate consultation.”

The nationwide survey, conducted across ten districts, used structured questionnaires combined with a Discrete Choice Experiment — a method widely applied in environmental economics to measure how people value trade-offs between development and conservation.

Ganepola noted that awareness of seabed mining remains low. However, once respondents were informed about potential impacts — including habitat destruction, sediment plumes, declining fish stocks and biodiversity loss — concern rose sharply.

“This suggests the problem is not a lack of public interest,” she told The Island. “It is a lack of accessible information and meaningful opportunities for participation.”

Ecology Before Extraction

Dr. Menuka Udugama said the research was inspired by Sri Lanka’s growing attention to seabed resources within the wider blue economy discourse — and by concern that extraction could carry long-lasting ecological and livelihood risks if safeguards are weak.

“Deep-sea mining is often presented as an economic opportunity because of global demand for critical minerals,” Dr. Udugama told The Island. “But scientific evidence on cumulative impacts and ecosystem recovery remains limited, especially for deep habitats that regenerate very slowly. For an island nation, this uncertainty matters.”

She stressed that marine ecosystems underpin fisheries, tourism and coastal well-being, meaning decisions taken about the seabed can have far-reaching consequences beyond the mining site itself.

Prof. Lahiru Udayanga echoed this concern.

“People tended to view deep-sea mining primarily through an environmental-risk lens rather than as a neutral industrial activity,” Prof. Udayanga told The Island. “Biodiversity loss was the most frequently identified concern, followed by physical damage to the seabed and long-term resource depletion.”

About two-thirds of respondents identified biodiversity loss as their greatest fear — a striking finding for an issue that many had only recently learned about.

A Measurable Value for Conservation

Perhaps the most significant finding was the public’s willingness to pay for protection.

“On average, households indicated a willingness to pay around LKR 3,532 per year to protect seabed ecosystems,” Prof. Udayanga told The Island. “From an economic perspective, that represents the social value people attach to marine conservation.”

The study’s advanced statistical analysis — using Conditional Logit and Random Parameter Logit models — confirmed strong and consistent support for policy options that reduce mineral extraction, limit environmental damage and strengthen monitoring and regulation.

The research also revealed demographic variations. Younger and more educated respondents expressed stronger pro-conservation preferences, while higher-income households were willing to contribute more financially.

At the same time, many respondents expressed concern that government agencies and the media have not done enough to raise awareness or enforce safeguards — indicating a trust gap that policymakers must address.

“Regulations and monitoring systems require social acceptance to be workable over time,” Dr. Udugama told The Island. “Understanding public perception strengthens accountability and clarifies the conditions under which deep-sea mining proposals would be evaluated.”

Youth and Community Engagement

Ganepola emphasised that engagement must begin with transparency and early consultation.

“Decisions about deep-sea mining should not remain limited to technical experts,” she told The Island. “Coastal communities — especially fishers — must be consulted from the beginning, as they are directly affected. Youth engagement is equally important because young people will inherit the long-term consequences of today’s decisions.”

She called for stronger media communication, public hearings, stakeholder workshops and greater integration of marine conservation into school and university curricula.

“Inclusive and transparent engagement will build trust and reduce conflict,” she said.

A Regional Milestone

Sudarsha De Silva described the study as a milestone for Sri Lanka and the wider Asian region.

“When you consider research publications on this topic in Asia, they are extremely limited,” De Silva told The Island. “This is one of the first comprehensive studies in Sri Lanka examining public perception of deep-sea mining. Organizations like the Sustainable Ocean Alliance stepping forward to collaborate with Sri Lankan academics is a great achievement.”

He also acknowledged the contribution of youth research assistants from EarthLanka — Malsha Keshani, Fathima Shamla and Sachini Wijebandara — for their support in executing the study.

A Defining Choice

As Sri Lanka charts its blue economy future, the message from citizens appears unmistakable.

Development is not rejected. But it must not come at the cost of irreversible ecological damage.

The ocean’s true wealth, respondents suggest, lies not merely in minerals beneath the seabed, but in the living systems above it — systems that sustain fisheries, tourism and coastal communities.

For policymakers weighing the promise of mineral wealth against ecological risk, the findings shared with The Island offer a clear signal: sustainable governance and biodiversity protection align more closely with public expectations than unchecked extraction.

In the end, protecting the ocean may prove to be not only an environmental responsibility — but the most prudent long-term investment Sri Lanka can make.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

How Black Civil Rights leaders strengthen democracy in the US

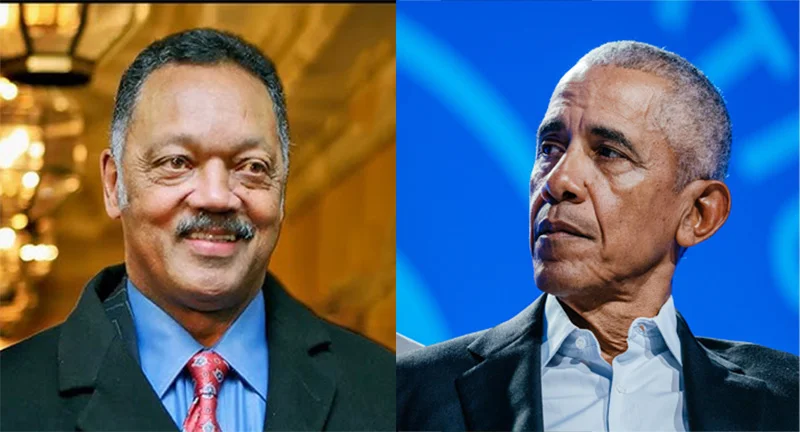

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

If this were not so, Barack Obama, an Afro-American politician, would never have been elected President of the US. Obama was exceptionally capable, charismatic and eloquent but these qualities alone could not have paved the way for his victory. On careful reflection it could be said that the solid groundwork laid by indefatigable Black Civil Rights activists in the US of the likes of Martin Luther King (Jnr) and Jesse Jackson, who passed away just recently, went a great distance to enable Obama to come to power and that too for two terms. Obama is on record as owning to the profound influence these Civil Rights leaders had on his career.

The fact is that these Civil Rights activists and Obama himself spoke to the hearts and minds of most Americans and convinced them of the need for democratic inclusion in the US. They, in other words, made a convincing case for Black rights. Above all, their struggles were largely peaceful.

Their reasoning resonated well with the thinking sections of the US who saw them as subscribers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, which made a lucid case for mankind’s equal dignity. That is, ‘all human beings are equal in dignity.’

It may be recalled that Martin Luther King (Jnr.) famously declared: ‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed….We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

Jesse Jackson vied unsuccessfully to be a Democratic Party presidential candidate twice but his energetic campaigns helped to raise public awareness about the injustices and material hardships suffered by the black community in particular. Obama, we now know, worked hard at grass roots level in the run-up to his election. This experience proved invaluable in his efforts to sensitize the public to the harsh realities of the depressed sections of US society.

Cynics are bound to retort on reading the foregoing that all the good work done by the political personalities in question has come to nought in the US; currently administered by Republican hard line President Donald Trump. Needless to say, minority communities are now no longer welcome in the US and migrants are coming to be seen as virtual outcasts who need to be ‘shown the door’ . All this seems to be happening in so short a while since the Democrats were voted out of office at the last presidential election.

However, the last US presidential election was not free of controversy and the lesson is far too easily forgotten that democratic development is a process that needs to be persisted with. In a vital sense it is ‘a journey’ that encounters huge ups and downs. More so why it must be judiciously steered and in the absence of such foresighted managing the democratic process could very well run aground and this misfortune is overtaking the US to a notable extent.

The onus is on the Democratic Party and other sections supportive of democracy to halt the US’ steady slide into authoritarianism and white supremacist rule. They would need to demonstrate the foresight, dexterity and resourcefulness of the Black leaders in focus. In the absence of such dynamic political activism, the steady decline of the US as a major democracy cannot be prevented.

From the foregoing some important foreign policy issues crop-up for the global South in particular. The US’ prowess as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ could be called in question at present but none could doubt the flexibility of its governance system. The system’s inclusivity and accommodative nature remains and the possibility could not be ruled out of the system throwing up another leader of the stature of Barack Obama who could to a great extent rally the US public behind him in the direction of democratic development. In the event of the latter happening, the US could come to experience a democratic rejuvenation.

The latter possibilities need to be borne in mind by politicians of the South in particular. The latter have come to inherit a legacy of Non-alignment and this will stand them in good stead; particularly if their countries are bankrupt and helpless, as is Sri Lanka’s lot currently. They cannot afford to take sides rigorously in the foreign relations sphere but Non-alignment should not come to mean for them an unreserved alliance with the major powers of the South, such as China. Nor could they come under the dictates of Russia. For, both these major powers that have been deferentially treated by the South over the decades are essentially authoritarian in nature and a blind tie-up with them would not be in the best interests of the South, going forward.

However, while the South should not ruffle its ties with the big powers of the South it would need to ensure that its ties with the democracies of the West in particular remain intact in a flourishing condition. This is what Non-alignment, correctly understood, advises.

Accordingly, considering the US’ democratic resilience and its intrinsic strengths, the South would do well to be on cordial terms with the US as well. A Black presidency in the US has after all proved that the US is not predestined, so to speak, to be a country for only the jingoistic whites. It could genuinely be an all-inclusive, accommodative democracy and by virtue of these characteristics could be an inspiration for the South.

However, political leaders of the South would need to consider their development options very judiciously. The ‘neo-liberal’ ideology of the West need not necessarily be adopted but central planning and equity could be brought to the forefront of their talks with Western financial institutions. Dexterity in diplomacy would prove vital.

-

Life style6 days ago

Life style6 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan