Features

Eighty years in Sri Lanka:The Life and Times of Fr. Vito Perniola SJ

By Avishka Mario Senewiratne

Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka

May 13, 2024

I always wonder how he did it? A simple, slender Italian priest who used the bus to get about. He was one who never compromised on discipline. A stickler for proper diction who spoke a manifold of Western and Oriental languages. A first-rate scholar who realized there was a single door one could walk in and outof between history and social linguistics. He embraced the Lankan heritage by becoming a distinguished citizen of the country just after independence.

Generations not born here will laud and praise the memory of Father Vito Perniola of the Society of Jesus for his exemplary efforts in publishing 19 definitive volumes on the Catholic Church of Sri Lanka. Abstemious by nature, and frugal in food, drink, clothes, and lifestyle, Fr. Vito Perniola was a shining example of plain living and high thinking.

Vito Perniola was born in Bari, South Italy on April 10, 1913, the fifth in a family of 11. His parents were Michele Perniola and Lucia di Gregorio, a well-to-do family. Deeply religious and conservative, they live a spiritual life, guided by their Parish Church. Though Vito’s father wanted him to pursue higher education as layperson, one event changed his life plans. While 11-year-old Vito was praying at the altar of St. Francis Xavier in his Parish Church, he received a strong calling to the priesthood. He discerned at that age that this was his true vocation; to be a Jesuit. With that conviction, he told his parents of his wish. Though upset, they consented.

Vito’s elder brother and two of his sisters would join different religious congregations. In 1925, at the age of 13 years, Vito joined the Society of Jesus. He was determined to be of the same order as St. Francis Xavier. In 1928, he joined the Jesuit Novitiate in Naples. From those early days, he displayed his great talents for studies. It was in Naples that he became aware of the Sacred Heart College, Shembaganur in South India from a catalogue of Jesuits institutions and seminaries. Realizing that this was the country where his saint hero, Xavier had been a missionary, Perniola was determined to receive his formation in India and later be a missionary in Ceylon, a country of which he had heard fascinating stories.

In his writings Perniola states that his time at Shembaganur were the best days of his life. Coming from a conservative Italian background, he encountered an all embracing setting in this part of the world. The weather here was sublime. It was here that he learned English for the first time. After four years of formation and philosophical studies in Shembaganur, Perniola departed for Ceylon, which was British Colony at the time. He had heard of the great work the Belgian and Italian Jesuits had done in the Jesuit Province of Galle since 1893.

In June 1936, Vito Perniola sat the Matriculation Examination. His subjects were English, Mathematics, Latin, Greek and Italian. Till he received his results he learned Sinhala. Perniola spoke fluent, grammatically correct Sinhala with a South Italian accent. He spent his time between serving in Parishes and teaching at St. Aloysius’ College, Galle.

When he was at the stage of deciding what field of studies to pursue, he made a choice that surprised many. He said to his superiors: “… Jesuits had already been in Sri Lanka for 50 years and yet nobody has studied Buddhism. Could I study Buddhism or Pali?” The Superiors supported Perniola’s intention. However, there was nobody within the Jesuit community who could teach him and provide him sources of references. This did not bother Perniola the least as he studied on his own, travelling across the country to study in the best libraries. Within a short time, he learnt both Pali and Sanskrit. He knew these languages better than most locals. It was decided that he be enrolled in Bachelor’s program at the University of London where he studied alone as there was no one to guide him.

In his early writing Perniola says: “The relationship between Pali and Sanskrit is very much like that of Italian and Latin. No Pali grammar can be written without reference to Sanskrit. For Sanskrit I had an excellent grammar; for Pali I had nothing worth the name.” Through perseverance and methodical study, he passed his exams and received his B.A. (Hons) in 1940. The best Pali scholars at the time were mostly German. Their texts elucidating Pali and Sanskrit were noteworthy efforts. To understand Pali better, Perniola studied German, a language difficult to master.

He entered the Papal Seminary, Kandy for his Theological Studies. It was during this time that World War II broke out and Italians in Ceylon were under scrutiny and some were sent for interment. However, the Bishop of Kandy, Msgr. Dom Bernard Regno OSB (an Italian himself), intervened and convinced his close friend, Governor Sir Andrew Caldecott, to spare the seminarians in Kandy. Accordingly, Perniola remained free despite the tensions of the War.

On June 21, 1943, Fr. Perniola was ordained a Priest by Bishop Nicholas Laudadio SJ at the Cathedral of Galle. After serving a few years in parishes such as Hiniduma, Fr. Perniola was appointed to the tutorial staff of St. Aloysius’ College, Galle in 1947. To his great disappointment, he did not have provisions to teach Pali, which was his speciality as there were no Pali classes in St. Aloysius.’ However, as there was a vacancy for teaching history, Fr. Perniola was assigned to teach that subject. It was during this time that he came to know Fr. S G. Perera, the revered historian, who was by then half-paralyzed and a resident of St. Aloysius’ College. Fr. Perera and Fr. Perniola developed a great friendship. Soon, with much support from Fr. Perera, Fr. Perniola had a sound knowledge and understanding of the history of Ceylon. It is ironic that an Italian taught Ceylon history to young Ceylonese boys!

Fr. Perniola taught history to the boys of St. Aloysius’ using the textbook prepared by Fr. Perera in 1932, History of Ceylon for Schools. This book which covered colonial Ceylon, was authoritative and scholarly textbook that remained the standard textbook of all Ceylon schools until the early 1960s. A few years after Fr. Perera’s death in 1956, Fr. Perniolal at the request of the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd., revised and enlarged Fr. Perera’s textbook. This was a useful contribution that the students and scholars of the time appreciated.

During the early 1930s, Fr. S. G. Perera had begun a project to document the history of the Catholic Church during the Dutch period. He had published a few of these documents, but the project was far from complete. Fr. Perniola took up the challenge to finish this work. In the process of understanding the documents of the Portuguese period, he learnt Portuguese. However, with other work in his ministry, he had to postpone this project. In 1949, Fr. Perniola received distinguished citizenship of the country, approved by D.S. Senanayake, the Prime Minister, and Minister of Defence and External Affairs.

Fr. Perniola was appointed Rector of St. Aloysius’ College for three years. During this period St. Aloysius College, dubbed by some as the ‘University of Galle,’ had some renowned educationists such as Frs. Julius Pogany, Chiriatti, Claude Daly, P. N. Peiris and many others. The school magazine contained scholarly articles by the staff and students. When this magazine, The Aloysian reached the Peradeniya or Colombo campuses of the University of Ceylon, readers were left amazed by the quality of the articles. A few years after his term ended, Fr. Perniola accepted Fr. Peter Pillai OMI’s invitation to join the newly established Aquinas College, Colombo as a lecturer in Pali, teaching the language to Arts students. At that time, Aquinas was affiliated to the University of London.

He enjoyed this new venture but realized that there was no Pali grammar textbook for students. Learning a new and complex language from scratch to degree level, warranted a well composed grammar book. For this purpose, Fr. Perniola himself compiled a textbook called Pali Grammar in 1958. This was one of the best textbooks ever on the language. Many Buddhist monks and others have studied Pali grammar referring to this book without even knowing that the author was an Italian Catholic priest. In 1997, the Pali Text Society of the University of Oxford republished this book as the official Pali Grammar.

Perniola was consulted by many scholars then and now. Dr. C. E. Godakumbura, Prof. Sucharita Gamlath and Dr. Ananda W. P. Guruge have warmly praised his linguistic efforts. Prof. Gamplath, in an article to Silumina on September 29, 2002, stated that “Existing Sinhala Grammars should be revised on the basis of Perniola’s insight”. Dr. Guruge in his autobiography titled Ma Vani Bilinda acknowledges his debt to Perniola’s guidance.

Fr. Perniola was a man with a tremendous sense of discipline in nearly everything he did. He always stuck to the rules and clauses of the language. Though his writings and works were grammatically perfect, at times he lacked style and elegance of writing. Fr. Aloysius Pieris SJ in his tribute to Fr. Perniola states: “It is also true that intense focus on the rules of the game sometimes prevented him from playing the game in style.

“ In 2013, Prof. Ven. Gnanaratana Thera, gave a professional assessment on Perniola, the grammarian (cf. Krinsansa, December 2013, pp. 144-153). The Ven. Thera states that Perniola followed a ‘middle path between overly philological and excessively traditional approaches to Pali grammar. He mastered the scriptural Pali as to have adduced rare, hitherto unmentioned examples of Pali usages to illustrate various grammatical rules.’

Furthermore, the Ven. Thera made a comparison between the German scholar Wilheim Geiger and Fr. Perniola saying the latter was more methodical and incredibly familiar with the language and idiom of Pali. Fr. Perniola’s dissertation on ‘Samasa’ (multi-barreled word compounds) resulted him being awarded a doctorate on linguistics from the University of Poona in 1966.

At Aquinas, Fr. Perniola taught Theology for many years. He was made acting rector when Fr. Tissa Balasuriya OMI was overseas. This was the time that the 1971 JVP insurrection took place. Fr. Perniola also served as the Vice Rector to Fr. W. L. A. Don Peter at Aquinas. During his stay in Colombo, Fr. Perniola became a popular figure among the laity. He was counselor and spiritual guide to many religious and laypeople. Despite his busy schedule, he always made himself available to anyone who sought his guidance. He compiled three useful books on meditation, namely, ‘Touching the Divine’, ‘Abiding in Love’ and ‘Praying with Scriptures’. These books went into several editions and over 10,000 copies have been sold. This has been an essential guide for many seminarians, priests as well as laypeople.

In 1972, Fr. Vito Perniola was appointed as the Provincial of the Jesuits in Sri Lanka. After his term ended, there was much pressure on why no one was continuing what Fr. S. G. Perera had begun on the Catholic Church history during the Dutch period. The recently retired Bishop of Chilaw, Bishop Edmund Peiris, appealed to Fr. Perniola to commence this work. This is how Fr. Perniola embarked on the project for which he is mostly remembered. With the support and blessing of Fr. Thomas Kuriacose SJ, the Provincial, Fr. Perniola started to gather documents for this monumental work.

In the late 1970s, he was awarded a scholarship by the House of Writers of the Society of Jesus in Rome and a research grant from Missio in Germany. This enabled him to travel to Rome, Portugal, and the Netherlands in the quest of tracking and procuring documents pertaining to the Dutch Period in Ceylon, collecting several documents on the Portuguese and British periods as well. He immediately realized that he would have to compile similar volumes for those periods too.

The translations of the Dutch period documents were not easy. With the help of the former Government Assistant Archivist, S. A. W. Mattau and number of other scholars Fr. Perniola translated Dutch and other documents of the period. Documenting the correspondence and reports of the early Oratorian missionaries such as Fr. Joseph Vaz and Fr. Jacome Goncalvez were noteworthy contributions. These documents reveal the cordial relationship between the Kandyan kings and Oratorian missionaries as well as the moderate attitude taken by the Dutch for the benefit of the Catholics during and after Dutch-Kandyan wars. Fr. Perniola quite objectively shares the documents of the time the missionaries fell out with the Nayakkar kings over mistakes on their part. Accordingly, between 1983 and 1985, Fr. Perniola compiled three large tomes on the Dutch Period.

These volumes impressed not only Catholics but also non-Catholics as well. It contained documents that no one ever imagined would see the light of day. These included correspondence of Kandyan Kings, Dutch Governors, Viceroys, Papal Secretaries, missionaries, and others. Fr. Perniola translated them in such a way that the discerning reader would easily understand them. If there were inconsistencies or inaccuracies in the letters, he would state them in the footnotes and give a far more comprehensive detail of what mattered. His works were well supplemented by a carefully compiled glossary, bibliography, and index. Clearly, a researcher who bases his work on these documents compiled by Perniola, can easily profit from them. Fr. Perniola’s introductions to each book sums up his ability to elucidate a sophisticated and well research twist of history. He gave a balanced, objective analysis of the period, people, and events he dealt with, often being critical of the mistakes made by religious missionaries.

Between 1989 and 1991, Fr. Perniola published three volumes on the Portuguese period. They ranged from the years: Volume 1: 1505-1565, Volume II: 1566-1619, Volume III: 1619-1656

When the British arrived in Ceylon, the country was divided into the Kingdom of Kandy and the coastal region which was under colonial rule. The Catholic Church of Ceylon was a single province under Cochin. It was only in 1845 that the island was divided into two vicariates: the Colombo (South) and Jaffna (North) Vicariates. In 1883, Kandy was made a separate Vicariate. After the establishment of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Ceylon in 1887, Colombo became an Archdiocese and Jaffna and Kandy became Dioceses. Six years later, the Diocese of Galle and Trincomalee were established. This is the reason why Fr. Perniola compiled 13 volumes on the British Period alone. As those years were close to the present, the number of documents increased by leaps and bounds. Essentially, he had enough content to compile a book covering each year.

In the quest of translating old documents written in a manifold languages such Portuguese, Latin, Dutch, French and others, Fr. Perniola states:

“I try to make the translation readable. Those who wish to study the style of an author, ought to go to the original. Thus, in some way the Italian saying remains true: traduttore, traditore (a translator is a traitor!). But while I have made the translation readable, I have tried to be faithful to the meaning of the text.”

Each and every book by Fr. Perniola was well accepted. Hardly anyone has ever taken the hard road he had in documenting over 10,000 pages of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. It is indeed a gigantic contribution. The final years of his life were very challenging as some blocked Fr. Perniola from tracing important documents of the period as they felt challenged. Nevertheless, his final book was published in 2011, when he was 97 years old.

His efforts in documenting history and Pali grammar were barely recognized by the Catholic Church. No one he associated with realized the importance of what he had been diligently working on in the twilight of his life. However, on the verge of turning 100 years, the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, of which Fr. Perniola was a member for nearly 70 years, awarded the prestigious Gold Medal of the Society which only a few scholars of yesteryear have been privileged to receive. This was a well-deserved recognition. Fr. Perniola continued writing short articles to the newspapers till he passed away in January 2016.

Fr. Perniola’s legacy will remain in the words and efforts of his very many books. There are many gaps yet to be covered and his 19 volumes on the Catholic Church would save years of research and money for the present and future scholar, for he had methodically included nearly everything relevant in these volumes. Essentially, if one owns these books, he or she has direct access to a well-set archive, supplemented by an index. Following are a few ideas and factors that can be derived after perusing Fr. Perniola’s books:

· The writing of an authoritative account of the history of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka

· Supplementing local history of Sri Lanka

· The writing of biographies of individuals, accounts of congregations, institutions, events and dioceses

· The reconciliation of past errors and the celebration of triumphant moments in history

· Inter-religious, inter-racial dialogue

Features

Provincialising universities: Risks and dangerous precedent of NEPF

by Nalaka Samaraweera

The new National Education Policy Framework (NEPF), currently being implemented by the government, has begun to be noticed by the public. However, there is a noticeable absence of an in-depth discussion on the implications of the policies it proposes. So far critics have quite convincingly pointed out the neoliberal motives behind the proposals and the threat that it poses to the longstanding tradition of free education in Sri Lanka. These criticisms hold merit, as the compilers of the framework have failed to present any moral stance, such as a commitment to social justice and equity, within the document.

An equally critical yet less emphasised aspect is the devolution agenda of the policy framers, who have aggressively pursued the decentralisation of educational powers beyond the provisions of the current Constitution. It is evident that their efforts are deliberate and explicit; they have unequivocally embraced the ‘Principle of Subsidiarity,’ challenging the unitary status of Sri Lanka. This principle was first introduced in Sri Lankan constitutional history during the attempted drafting of a new Constitution by the ‘Yahapalana‘ government in 2016 receiving severe criticism for undermining the country’s unitary status.

Strangely, the NEPF framers have adopted the same principle despite the nation’s continuing adherence to the unitary status. It appears that the NEPF framers disregard the necessity for policies to align with the Constitution, as evident from the multiple recommendations that violate the provisions of the 13th Amendment. For instance, the NEPF recommends stripping the government of the right to establish universities, conferring that authority exclusively upon provincial administrations.

Additionally, it suggests categorising existing universities as “provincial universities.” This recommendation contradicts the Constitution, which defines the establishment of universities as a concurrent task shared by both the central and provincial governments. Moreover, it has been recommended that the Provincial Boards of Education, entrusted with the advisory function by the Constitution, be granted autonomy by the NEPF.

It is further recommended to replace the University Grant Commission (UGC), the apex body of higher education, with a new entity called the National Higher Education Commission, whose role is to be limited to maintaining academic standards adhering to the national policies. As a result, the Provincial Boards of Education take on the roles of establishing, coordinating, and maintaining universities, thereby challenging the existing centralised authority over these responsibilities.

The framers are doubtlessly intent on fully devolving higher education in the country to a degree that surpasses even India’s model, where the Union Government shares the powers with states to establish, coordinate and maintain universities. What’s actually concerning is their daring attempt to decentralise higher education not by directly amending the Constitution, but by manipulating education policy decisions, which is both unconstitutional and unethical.

What could be the consequences of this attempt with regard to universities? So far, universities have featured in national political mandates with promises to increase the number of institutions and student enrollment, driven by a sense of national interest beyond regional and ethnic considerations. However, if universities are transformed into “Provincial Universities” and become focal points in provincial election campaigns, these campaigns may emphasise regional sentiments. When local politicians view universities primarily as tools to serve their regional constituencies, they are likely to undermine the national significance of these vital institutions. This shift challenges the current equitable approach, which strives to serve the national interest without regard to regional or ethnic differences.

The NEPF aims to replace the UGC and transfer the responsibility of funding universities to respective provinces, posing a significant threat to university autonomy. If provincial bodies gain authority to fund universities while heavily relying on government funding, we can expect increased corruption and deficiencies. Local politicians are likely to prioritise regional sentiments. Additionally, there is no assurance that all universities will receive equitable treatment, as their affiliations with different provinces may lead to disparities.

It was not long ago that there was a media report of a politician sending a letter to the top authority of a university, advocating for the recruitment of a specific individual as a lecturer. If this is happening even when universities are buffered by the UGC from direct political interference, the situation could worsen if they fall under the oversight of the proposed autonomous Provincial Educational Board. There is no doubt that this board would be influenced by provincial political dynamics. Imagine a scenario where the Provincial Chief Minister appoints the Vice Chancellor of the “Provincial University.” In this scenario, provincial politicians might view universities as potential employment hubs for their constituents.

It is no secret that there is an infamous demand for the further division of existing provinces along ethnic lines in this country. In this context, if ethnicity-focused groups see universities as instruments for promoting ethnic and religious interests rather than fostering a cohesive national identity, the country will lose its ability to create a unified national ethos. It is inevitable that universities will become victims of regional and ethnic political maneuvering.

Why are the framers of the NEPF persisting in this unconstitutional endeavour? Why haven’t they opted to pursue amendments to the Constitution for their intended devolution through proper channels? Perhaps, they are leveraging this for future constitutional amendments when the political climate is favourable to such endeavours. The public is strongly urged to remain vigilant regarding potential future constitutional changes, as the irreversible damage they may cause has been well documented.

It is important to note that Sri Lanka, unlike India, does not accept provincial autonomy in principle due to its unitary status. If there is a need to delegate certain powers, be it legislative, administrative, or financial, it must be approved by Parliament. In this context, I would like to pose a fundamental question: What is the rationale behind provincialising universities? Put differently, do specific provincial needs and conditions warrant such a recommendation in the Sri Lankan context? Is there any need for distinct higher educational programmes to cater to unique requirements in provinces? If it is posed more concretely, do provinces have unique industrial and manufacturing activities that demand tailored engineering and managerial degree programmes specific to the province for example? To the best of our knowledge, no one has been able to demonstrate such distinct requirements. Authorities need to remember that the rationale behind devolving power should stem from logical arguments rather than merely pleasing certain groups for future political gains.

Let the people be urged to unite in opposing the NEPF, which will set a dangerous precedent by surpassing the provisions outlined in the Sri Lankan Constitution. Failure to do so would lead to a precedent of devolving power through policy manipulations, without amending the Constitution.

(The writer is a Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa. Views expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

AI, climate control,and Buddhism

By Rohana R. Wasala

Addressing a gathering as chief guest at the 100th anniversary celebration of the Sri Lanka Buddhist Society Moratuwa held at the Moratuwa Buddhist Society Hall on May 11, 2024, President Ranil Wickremesinghe pledged Rs. 1 billion for research to ‘explore the connection between Buddha’s teachings and AI’ starting next year as The Island (Online) reported 13 May, 2024. He revealed that though the project was scheduled to start this year, it had to be deferred for lack of legal provisions for the regulation of Artificial Intelligence (AI). The programme will go ahead once new laws are adopted by parliament, he assured. The President also said that the government would provide the funds required for the restoration of the Moratuwa Buddhist Society Hall ahead of its own first centenary in 2029 (The construction of the building was completed in 1929).

The president’s determination to exploit AI for the global promotion of Theravada Buddhism was first mooted in a statement he made as guest of honour at the inaugural function held at the Edward Stadium in Matale, a day ahead of the 73rd National Upasampada Maha Vinaya Karma of the Ramanna Nikaya, which was to be conducted at a venue in Bandarapola, Matale from July 20 to 27, 2023. Video. Before commenting on this ludicrous subject of a costly programme of research on a hypothetical relationship between Buddhism and AI, an obvious case of comparing apples and oranges, let me turn to what else the president said at Moratuwa.

President Wickremasinghe laid similar emphasis on the global issue/s of climate change involving atmospheric warming and worsening water scarcity, both currently experienced in Sri Lanka. He thought that these challenges are to be met in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha. His arbitrary assertion in this connection is that, in terms of the Buddha’s teachings, ‘this issue’ (of climate change) ‘stems from civilisation’s greed for rapid progress’. The president would have been more convincing in making this claim (if he actually did so, as reported) had he mentioned the particular discourse or context where the Buddha allegedly talked about climate change. Since the president didn’t do so, his audience probably took him at face value. I, for one, don’t think that Buddhism offers any answers to climate change issues. The Buddha never claimed omniscience regarding the physical world, world-systems, or universes (cakkavala/chakravata in Pali and Sanskrit respectively, and sakvala in Sinha), which he said is achintya, meaning surpassing human thought, inconceivable, an idea modern physicists accept).

The subject of ‘loka’ or the world (there’s a special definition of the word ‘loka’ in Buddhism) is beyond thought (Sin. loka vishaya achintyayi). Gautama Buddha was the world’s first exponent of what is today known as the scientific method, which is important in any field where identifying and solving problems are involved, including climate control. He used it for discovering the Four Noble Truths about human existence: the reality of the unsatisfactoriness of samsaric journeying, its causes, the possibility of stopping that aimless wandering, and the way to achieve the cessation of the endless cycle of repeated reincarnations that is full of ‘dukkha’ or suffering. This goal has to be reached through wisdom while practicing universal love and compassion (lovingkindness) over all sentient beings.

‘Buddhism integrates our spiritual understanding with our experience of the natural world’ a Western scholar speaking about Albert Einstein’s view of Buddhism says (Source: ‘Dream Sparks’ YouTube channel). Albert Einstein is celebrated as the 20th century’s greatest scientist. Einstein stated that the Buddha had found what he was searching for. The following is a popular quote from Einstein: ‘If there were any religion capable of aligning with the demands of discoveries of modern science it would indeed be Buddhism’. So, there is no need to make false claims involving AI or climate control on behalf of Buddhism to extol it in order to raise its image in the world.

Incidentally, The Island (Online) report (May 13) which is my source here doesn’t say whether, in his speech, the President made any grateful mention of Arthur V. Dias (1886-1960) under whose leadership the Moratuwa Buddhist Society was established. The Moratuwa Buddhist Society Hall was built under his sponsorship, too. Most probably, being a sort of history buff, the President did talk about Arthur V. Dias, though the newspaper report makes no mention of it. If he didn’t, by any chance, (which is unlikely), it would be a regrettable lapse on his part. This patriotic Sri Lankan used to be one of the national heroes annually honoured in our school days from the early 1950s to mid1960s. He is still fondly remembered by at least a few grateful Sri Lankans, as kos mama, who was a successful planter, philanthropist, temperance movement member, and freedom activist. If he were living today, he would definitely have said and done something to tackle these problems.

To resume the subject of a hypothetical relevance of Buddhist teachings to climate control, the issue of harmful effects of uncontrolled human activities on climate was most unlikely to have been encountered in India in the time of the Buddha two thousand five hundred years ago, nor anywhere else in the rest of the world for that matter. Nowadays, however, it is a huge problem that impacts life on the Earth generally, and that seriously impairs the quality of human life and humanity’s physical and mental wellbeing. It could be even worse than that unless remedied. Renowned British broadcaster, TV presenter, film-maker, biologist, natural historian and popular author David Attenborough (b. 1926) mentions changing climate among the factors that make him conclude that “we are finally fast approaching the Earth’s carrying capacity for humanity” (A Life on Our Planet/2020), that is, its ability to support human life in terms of a healthy environment, good climate, clean water, food, fuel for factory engines and transport vehicles, electricity power for lighting homes and cities and running industries, and so on.

The President was reported to have blamed climate change on what he called humanity’s ‘greed for progress’. Probably he had in mind the same sort of problems that David Attenborough suggests ways to deal with in the book mentioned. But material progress is a good thing that should be desired. Only unconscionable greed for material wealth in a poor country like Sri Lanka where the majority of the people live in poverty is bad.

The survival of traditional institutions such as religions depends on their perceived relevance to the day to day life of a community. The president is aware of this fact. That must be why he appears to be taking a special interest in serving the cause of Buddhism by researching a possible relationship between AI and Buddhism, and also by trying to establish a source of intellectual support in Buddhism in the matter of climate control.

However, instead of turning to Buddhism for solving this mundane problem, we could listen to Bill Gates, former CEO of software giant Microsoft and its principal co-founder, technologist, businessman, investor, and philanthropist, who spent a decade investigating the causes and effects of climate change with the help of experts in diverse fields including physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, political science, and so on. He found three broad areas that should receive vital attention if certain climate disaster is to be avoided. These he lists on page 8 of his book ‘How to Avoid a Climate Disaster’ (2021): To paraphrase, these include 1) bringing the 51 billion tons of greenhouse gases that the industrial world typically releases to the atmosphere every year down to zero, 2) deploying the tools that we already have like solar and wind power faster and smarter, and 3) creating and rolling out breakthrough technologies. The whole book is a carefully integrated elaboration of these basic themes in twelve chapters, that discuss problems connected with, for instance, use of fossil fuels, generation and consumption of electricity, agronomy (soil management and crop production), safe use of fertilisers, management of water resources, etc., and the crucial issue of the importance of conducive government policies. I mention these things to show that we need to consult local counterparts of specialists from diverse fields whose expertise that Bill Gates drew upon. Sri Lanka already has a lot of qualified young scientists to play that role without having to depend on Buddhism in lazy complacency, except perhaps as a source of moral inspiration.

Incidentally, Bill Gates claimed in his website ‘GatesNotes’ in 2018 that he and his wife Melinda took to meditation as a way to ‘exercise’ their minds, following, as evident in the context, the guidance of former Buddhist monk Andy, who seems to combine both the Burmese (Theravada) and the Tibetan (Vajrayana, a form of Mahayana) traditions. But this doesn’t mean that Gates adopted Buddhism as a religion.

He was originally reluctant to practice meditation because of the connection he thought it had with the concept of reincarnation, which, obviously, he didn’t accept. Nevertheless, Buddhist teachings can after all be said to have been indirectly relevant to the Gateses’ climate control activism. When Gates says he took to meditation to ‘exercise’ his mind, he most likely means the same as what we normally mean when we say that we meditate at least as a minimal goal, to gain control over our thought process in order to ‘calm’ our minds, gradually achieving a state of mental tranquility, peace and balance, that enables us to use our mental and physical energies for best effect in our intellectual and physical exertions. I added this information to suggest that the moral ethical teachings of Buddhism help Buddhists and others who choose to follow them to focus their mental as well as physical energies on the performance of the required tasks to achieve any desired goal. (To be continued)

Features

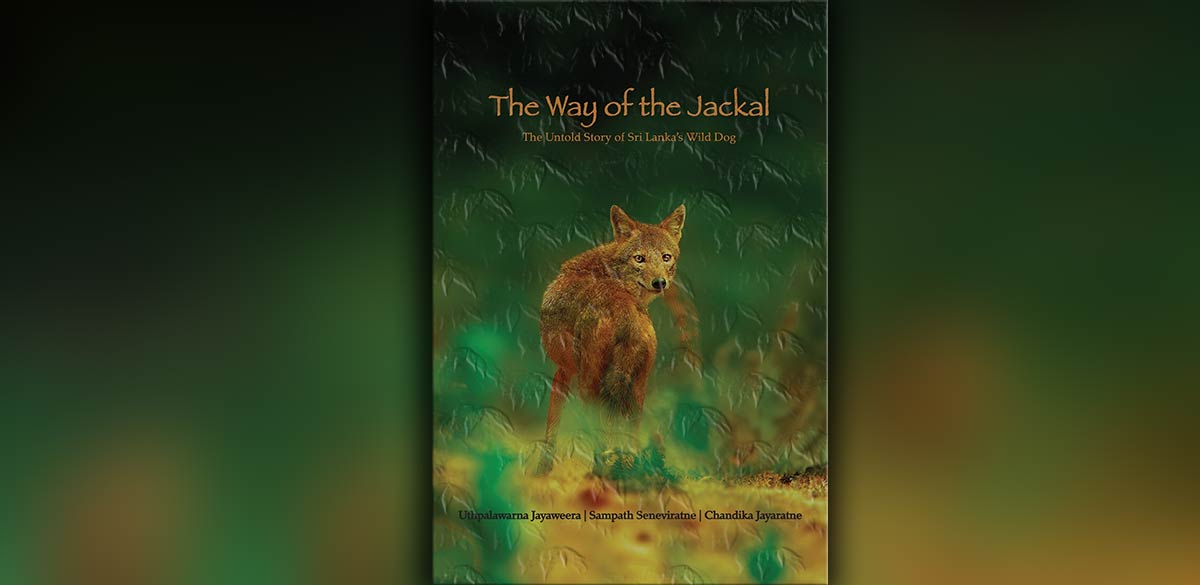

The way of the jackal

By Ifham Nizam

Sri Lanka’s jackal is the only subspecies of the Eurasian Golden Jackal across its range. Historically, it was even considered a species endemic to Sri Lanka.Being the solitary wild dog inhabiting the island, it ranks as the third-largest carnivore in the area, surpassed only by the majestic Leopard and the leisurely Sloth Bear. Despite these remarkable attributes, this creature remains largely unnoticed.

Its grace eludes photographers, its beauty escapes artists’ canvases, tourists seldom seek glimpses of it, and scientists have overlooked its study. Instead, the tale of our Nariya fades into folklore—a misunderstood being, relegated to the shadows of indifference.

Presented in clear language across 152 pages and adorned with over 100 captivating colour photographs, “The Way of the Jackal” offers a thorough exploration of this species, catering to wildlife enthusiasts, biologists, and students alike. Delving into the Jackal’s physical traits, behaviours, social dynamics, and vocalizations, this comprehensive work also equips readers with field-tested techniques for studying the species, strategies for mitigating conflicts, and insights into its potential as a key attraction in wildlife tourism.

By shining a spotlight on the Nariya of rural lore, this book aims to ignite interest, spur research efforts, foster conservation initiatives, and tap into the untapped economic opportunities presented by Sri Lanka’s wild dog population.

Authors:

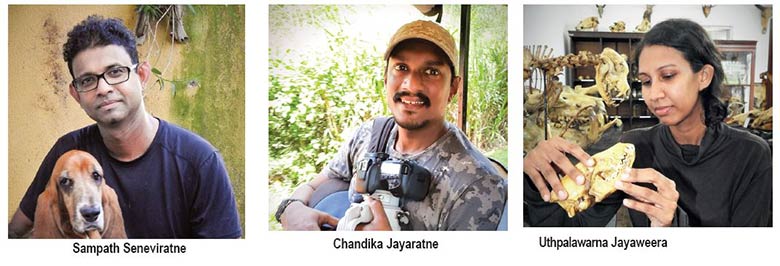

Uthpalawarna Jayaweera is a Science graduate majoring in Zoology at the Department of Zoology and Environment Sciences, University of Colombo. She is a keen researcher who studies carnivore ecology and evolution.

Prof. Sampath Seneviratne is a professor attached to the University of Colombo. He also is a research scientist, a forester, a conservationist, and a public communicator. Sampath spends time in forests across the globe, mostly away from popular places. He loves birding, tracking wildlife and planting.

Chandika Jayaratne is a graduate from the University of Staffordshire in the UK. He pursued a career within the field of hospitality and environmental stewardship. He also has a research background where he studies the ecology of Rusty-spotted Cat and Jackal.

The Island interviewed the three authors regarding their most recent research on Sri Lankan jackals.

Briefly, whose brainchild and how did it kick start?

In Africa, the jackal species found in the northern regions, once considered an African subspecies of the golden jackal, was reclassified as a distinct species of wolf in 2015, following a molecular phylogenetic study conducted by a team of scientists. This discovery served as the catalyst for initiating a project focused on the Sri Lankan jackal.

Our jackal holds a unique position as the sole wild canine species in Sri Lanka and stands as the only island subspecies within the range of the Golden Jackal. The confusion related to its taxonomic status, lack of proper scientific studies on its ecology, and neglect of its potential as a high-value species in Sri Lankan tourism have prompted the need for comprehensive research on this amazing species

Recognizing the Sri Lankan jackal as a promising research model and a valuable asset in Sri Lankan tourism, the project commenced with an investigation into various aspects of the species’ ecology. This included studies on diet, vocalization, taxonomy, geographical distribution, the nature of human-jackal interactions, and the current status of the population. After three years of dedicated work, the culmination of our efforts resulted in the publication of a comprehensive book on the subject.

What are the main species of jackals discussed in the book, and what are their distinguishing characteristics? I understand the species differ from the species stated by W W A Phillips.

There are mainly three species of jackals in the world; Black-backed Jackal, Side-striped Jackal, and Golden Jackal.

The Black-backed jackal (Lupulella mesomelas) is a medium-sized canid native to eastern and southern Africa. The characteristic features of this animal is the dark saddle that extends from the base of the tail to the neck. In addition, they have a long, pointed snout and an overall rufous brown body colour.

The Side-striped Jackal (Lupulella adustus) is a canid native to central and southern Africa. There are two distinguishing characteristics that aid in identifying this animal: a prominent white tip on the tail, and white or off-white sides stripes on the sides

The Golden Jackal (Canis aureus) has the widest range of all jackals. It has a mixture of black, brown, and white hairs in its back fur, giving the impression of a dark saddle, though not as prominent as in black-backed jackals. They range from Europe to the Middle East, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, including Sri Lanka. So the jackal species that lives in Sri Lanka is the golden jackal and there are 13 subspecies of golden jackals in the world. It is widely believed that the same subspecies is found in the southern parts of India and in Sri Lanka, named Canis aureus nariya.

However, when reviewing the Sri Lankan jackal’s taxonomic history, using published scientific literature and specimens in major museums, such as the Natural History Museum of Colombo, the Museum of the Bombay Natural History Society, and the Natural History Museum of London, we found that:

According to some authors, our jackal is considered a subspecies native to both southern India and Sri Lanka, named Canis aureus nariya. Others see it as a subspecies endemic to Sri Lanka, named Canis aureus Lanka. Also, our jackal has even been considered a unique species, endemic to Sri Lanka, by Wroughton (1916), and Phillips (1935), named Canis Lanka.

As you can see, there is clear confusion regarding its taxonomic status. However, all these classifications have been made, based solely on morphometrics. Therefore, we stress the importance of molecular phylogenetic studies to clarify this taxonomic ambiguity.

How do jackals interact with their environment, and what roles do they play in their ecosystems?

Jackals are considered essential ecosystem service providers due to their pivotal role in pest control within agro-ecosystems. Their diet primarily consists of significant pests, such as rodents, wild boars, peacocks, and granivorous birds like munias. By preying on these pests, jackals help maintain the balance in agricultural environments and reduce crop damage.

In addition to pest control, jackals also serve as nature’s cleaners and health care providers. They scavenge on carcasses and hunt diseased and weak animals, thereby preventing the spread of diseases within the wild and beyond. This scavenging behaviour helps maintain the overall health of the ecosystems they inhabit by removing potential sources of disease. In a country like Sri Lanka, where vultures are absent, the role of jackals, as scavengers, is particularly crucial.

What are some unique adaptations that jackals possess for survival in their habitats?

Jackals are highly adaptable creatures, known for their generalist and opportunistic feeding behaviours. As omnivores, they consume a diverse range of food, including small mammals, birds, reptiles, fruits, carcasses (such as ungulates), insects, and even human food. This high degree of dietary versatility allows them to switch food sources when a particular prey becomes scarce.

Jackals are also capable of thriving in a wide array of habitats, including grasslands, wetlands, forests, valleys, seashores, and areas near human settlements. Their adaptability extends to extreme environmental conditions as well. In Europe, for example, they can inhabit elevations ranging from 1,200 to 2,350 meters and can withstand temperatures as low as -35°C. This remarkable flexibility in both diet and habitat allows jackals to occupy diverse ecological niches and play a crucial role in various ecosystems.

How do jackals communicate with each other, and what social structures do they exhibit?

Like all other canids, jackals exhibit three primary modes of communication: vocal, olfactory, and visual. Jackals use their urine and feces to leave scent marks, which serve as messages to others, especially for marking territory.

Regarding their social structure, the basic social unit of jackals is the breeding pair. It is widely believed that in Golden jackals, the breeding pair mates for life.

What is the hunting behaviour of jackals like, and how do they procure their food?

Our questionnaire survey on the jackal diet showed several interesting behaviours. Jackals are known to visit paddy fields in search of prey, like crabs and rodents. They are also notorious for raiding chicken coops, especially those located near the borders of villages. In certain areas, villagers have observed that jackals howl when they find food. In other regions, it is believed that their howls help to flush out prey, such as Black-naped Hares, from their hiding spots.

Additionally, scavenging is a common behaviour among jackals. Their food may consist of cattle, deer, wild boar, and even elephants that have been killed by predators like leopards, struck by vehicles, or have died from disease or natural causes.

In what ways do jackals interact with human communities, both positively and negatively?

Jackals may be drawn to areas where food is readily available, such as garbage dumps, livestock holdings (including chickens, rabbits, and goats), and paddy fields. Additionally, rabid jackals might enter human settlements due to their increased aggressiveness, fearlessness, and other behavioural changes caused by the disease.

Are there any myths, folklore, or cultural representations of jackals discussed in the book?

Jackals are deeply embedded in folklore, cultural representations, and myths, possibly being the animal most frequently mentioned in our culture, including art, literature, and folklore.

In our folklore and literature, such as “Magul Kema” and stage plays. like “Nari Beana,” the jackal is predominantly depicted as an opportunistic trickster. Art from the Kandyan period often features the jackal in religious contexts, such as in the “Sasa Jathakaya,” which depicts the earlier lives of Gautama Buddha in animal form.

Several famous myths are associated with the jackal. One prominent belief among rural folk is that occasionally a jackal can develop a horn, known as a ‘Jackal Horn,’ ‘Nari-comboo,’ or ‘Nari-anga,’ which is thought to possess magical powers.

What scientific research methods are used to study jackals, and what have these studies revealed about their biology and behaviour?

There are various methods to assess different aspects of jackal ecology. For example, camera traps, thermal imaging cameras, and radio tagging are commonly used to study their behaviour and interactions with other carnivore species.

In our study, we conducted the first-ever dietary analysis of jackals using their scat and stomach contents of road-killed jackals. We found that their diet mainly comprises four types of food: small mammals, birds, invertebrates, and plant-based foods. The presence of a wide variety of items, including rodents, like the black rat (Rattus rattus), grassland birds such as the Tricoloured Munia (Lonchura malacca), invertebrates like beetles and maggots, and plant materials such as jackfruit, bananas, grasses, seasonal berries, and even human food (e.g., cooked rice, scraped coconut, and onion), indicates that our jackal is an opportunistic omnivore rather than a specialist predator.

Even near visitor bungalows, deep inside wildlife parks, surrounded by pristine wilderness, we found jackal scat containing human food remains, such as rice and onion peels. This suggests that jackals prefer easily obtainable food over expending energy on hunting. Therefore, they might frequently visit human habitations in search of such food.

Additionally, we characterized jackal vocalizations for the first time using the playback acoustic method. Through this, we identified different syllables that form five distinct vocal types: the bark, whine, whimper, short-lone howl, and group yip howl. Our findings indicate that the group yip howl is the main vocalization and major group vocal display, primarily associated with reunion and territorial defence.

How do jackals adapt to changing environmental conditions, such as climate change or human-induced alterations to their habitats?

Due to their higher dietary flexibility, jackals can switch to alternative food sources if one type becomes scarce because of climatic changes or human-induced alterations. They generally prefer shrub jungles with higher visibility, as these habitats provide abundant and easily accessible small mammals, like rodents. This preference allows jackals to thrive even in small, isolated patches of jungle, as well as in monocrop plantations, such as coconut, oil palm, rubber, and paddy fields.

However, despite their adaptability, jackals still require certain minimum habitat conditions to survive. If these conditions are not met, they may eventually disappear due to the loss of feeding and breeding grounds to support their survival.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLT-MOBITEL & STEMUP Educational Foundation successfully complete first batch of “CoderDojo”

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoDialog takes personalisation to new heights with AI-driven greeting cards, powered by Star Points

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoRansomware menace plagues Sri Lankan businesses: Kaspersky

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoPRCA Country Rep calls for ethics and standards in Sri Lanka’s advertising and marketing industry

-

Fashion1 day ago

Fashion1 day agoKhalida, young entrepreneur plays colours and textures

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog launches cutting-edge 4G vehicle tracking solution

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe digital divide: AI and its implications for higher education in Sri Lanka

-

Life style1 day ago

Life style1 day agoMinor Hotels Introduces NH Collection and NH Brands in Sri Lanka