Opinion

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

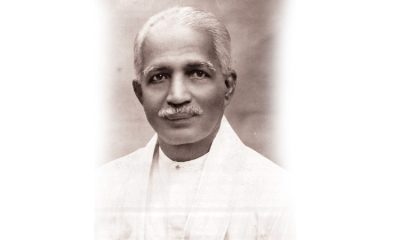

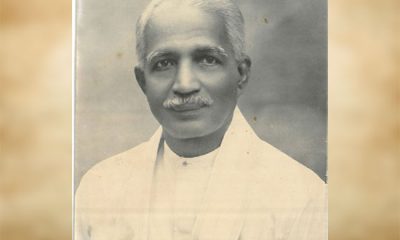

The 32nd Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara Memorial Lecture titled ‘For a country with a future’: Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today’ delivered by Prof. Athula Sumathipala, Director, Institute for Research and Development, Sri Lanka and Chairman, National Institute of Fundemental Studies, Hanthana on Oct 13 at the National Institute of Education, Maharagama

Continued From Yesterday

Have these educational reforms from 1947 to date resulted in a sufficient number of citizens who are ready to face the 21st century, citizens who think beyond personal gain, and developed teachers, intellectuals, educationists and politicians, who have the capacity and the will to help develop such persons? The reality, however unpleasant, is that, no, it has not.

Has the Kannangara vision become a reality?

The aim of widening access to education was to help develop citizens, teachers, intellectuals, educationists and politicians, with the capacity and will to think beyond personal gain. Did such increased access achieve this aim? Or did it unexpectedly result in a process of converting the educated few among the poor into wealthy individuals and members of the elite? And in political power moving into the hands of a significant percentage of people who focus primarily on their rights and not on their duties and social responsibilities?

How did Israel which was established as a country in 1947 end up a developed country whereas Sri Lanka which established free education in 1947 end up a bankrupt nation? How did Sri Lanka which had the second strongest economy in Asia at the time of its independence in 1948, next to Japan alone at the time, fall so far? Can we escape this crisis without examining the factors for this fall? Why did progressive thinking not develop in line with widened access to education?

According to our conclusions based on behavioural science, economics, humanities, sociology, psychology and political science, the factors driving the current social, economic and political crisis are:

• Political leadership without a vision: the primary factor is the political leadership that governed the country post-independence, and particularly after 1977, and the narrow political vision

• Severe failures within political structures: most politicians are not honest representatives who hold themselves responsible to the public

• Corruption: politics has turned into a mechanism where wealth can be earned using the power and benefits available to politicians

• Wrong economic policies and management: failure to protect export income, import costs exceeding export income and unlimited borrowing to cover the discrepancy between dollar earnings and expenditure

• The decline of the quality of the government service: government service becoming inefficient, corrupt and suborned by political power

• Weakened moral fibre of the people: Perpetuating ignorance and poverty for political gain, failure to empower people and inculcating a mentality of dependence founded on a focus of rights alone and a disregard of duties and responsibilities

The common factor tying up all that is stated above is the lack of an education system that can engage and triumph over local and international challenges, that can ensure developing skilled and productive citizens. A key reason for this failure is the lack of a State Education Policy, which resulted in each successive government implementing disparate policies during their times. In the same vein, student organisations and trade unions carried out protests based on political motivation rather than societal needs. The solution to all issues can lie in high quality educational reforms which consider the Sri Lankan nation as a single entity.

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

Educational reforms necessary today cannot be discussed in isolation from the global situation; they must be viewed within a broad framework of global economic crises as well as the Covid pandemic since the entire world has been turned on its head by the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 1950, Rene Dubois, a French microbiologist, environmentalist and humanitarian, who later became the Professor of Community Medicine and Tropical Medicine at the Harvard University, warned that nature would attack back at an unexpected time, in an unexpected manner. This is what we saw in 2019. The high-risk behaviour of humans, pollution, destruction of forests, use of anti-microbials, changing biomes, chemical pollution, urbanisation, rapid population increase, ultra-consumerist culture challenging sustainable limits have led to the destruction of the environment. Most people remain unaware that the floods, landslides that we call natural disasters are not in fact natural but are a result of human actions.

Faced with this unpleasant truth, education today should move towards an in-depth analysis of how we should educate ourselves to protect humanity by overcoming these challenges. It is necessary to re-examine our thoughts, feelings and behaviour in the face of the global challenges we need to overcome. Therefore, the aim of Sri Lankan education and educational reforms should be the development of a child, an adult and a citizen who looks at the world from a new perspective and is sensitive to humanity; who aims to leave a future that is better than our past to our unborn children. It is my duty to remind everyone that there is no other alternative left to us.

This country requires citizens, teachers, intellectuals, educationists and politicians who have the skill and the ability to support the development of children and people who can face and manage change, and have a vision beyond personal gain. This is therefore the best time to discuss broad educational reforms which can support the challenges of this generation. In this context, what is essential are educational reforms which go beyond expanding access to education and changing curricula, or reforms which consider development of dollar-earning, exportable human resources as their only objective. The demand today is for reforms that go beyond these basic aims and aim to enhance morality and human values.

Gaveshana Magazine, of which I am a member of the editorial board, recently published its 39th special edition on the theme of ‘Educational reforms the country demands to develop a productive citizen adaptable to the modern world’. Professor Gominda Ponnamperuma, Head of the Department of Medical Education of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo stated as follows in writing an article on ‘Student-focused education and traditional education in Sri Lanka’ for this edition:

“The education system that exists in Sri Lanka today is not one that has identified the needs specific to Sri Lanka, develops human resources to match those needs, nor one that has been enriched by the positive aspects of global trends in education. What exists today is the education system developed by British colonials. This system is not currently practiced even in Western countries. Those countries too have given priority to student-centred education. The student-centred education system we believe in is closer to the education system we originally had in Sri Lanka rather than to the system that was forced on us by the British, that they themselves reject today, but that we continue to maintain.

What is the student-centred education system we believe in? This concept is based on the definition of the word ‘education’. Currently, education is defined as skills to be developed through understanding, experimentation and experience, rather than material that can be transmitted from one person to another.

If education is a resource that flows inertly from a teacher to a student, then, education can be limited to confining a group of students to a room, and a teacher providing a series of lecture notes according to a set timetable. Yet, education is not thus defined. In that case, what defines student-centred education? True education, as previously defined, should be a process where a student, together with other students and a teacher, engages in effective conversation, allied student experiments, experiences and activities, leading to the acquisition of mental and physical skills as well as conceptual and spiritual change. It is however questionable if this is feasible in a school classroom of today?

For this to be feasible, there needs to be an environment where students can form small groups in a classroom to carry out experiments and discuss experiences under the guidance of a teacher, leading to intellectual, physical and conceptual development in the children. However, the classrooms of today are only suitable for information transmission from the teacher to the student, and not for conceptual and intellectual development through discussion between the student and the teacher. Continuing in this vein will prolong a ‘memorising education culture’ that dulls critical thinking. For future Sri Lanka to have an intelligent, skilled work force with strong values, the current classroom structure needs to change.

A counterpoint to this claim is that a teacher is weakened in student-centred education. That is completely false. In teacher-centric education, the teacher prepares notes and passes it on to the students. The teacher then explains anything the students do not understand. Students then learn the teacher-provided notes and reproduce such learnings at an exam. In student-centred education, the teacher develops ‘learning stimulants’ that need to be discussed and experimented on with students, for example, documents, reports of practical applications, activities to engage in. Students explore the stimulants the teacher developed, in small groups. The teacher directly participates in such discussions and experiments and explains any confusing or difficult points. The teacher consistently assesses if the students have reached the educational targets and objectives.”

The explanation above indicates how student-centred learning can further strengthen the role of the teacher rather than weaken it, and how it can lead to greater creativity and enjoyment in the profession of teaching.Pre-colonial Sri Lanka had an education system which is the polar opposite of teacher-centric education. In this system, the teacher would identify the skill set best aligned with the student and would teach the student either fencing, or archery, or irrigation methods, or agriculture and so on. It is quite student-centric since the teaching content and method is modified to suit the needs of each student, rather than a ‘one size fits all’ education methodology that assumes a single teaching and learning methodology meets the requirements of all students.

As we pointed out previously, education is well-known in this country as something that should have, but has not, evolved. Last year, this task of educational reforms was assigned to the Educational Reforms and Distance Education State Ministry. Dr. Upali Sedere, Secretary to this Ministry, disclosed in a special article for Gaveshana magazine the proposed reforms, which are due to be enacted under the current Minister as well.

The reforms are based on six key objectives:

i) active contribution to national development

ii) effective and efficient work-oriented person

iii) person with entrepreneurship mind

iv) patriotic person

v) good human being

vi) happy family

The curriculum that is based on these factors consists of four separate parts:

i) scholarship

ii) productive citizen and activity-based education

iii) teamwork

iv) emotional development

This will be structured on a modular method, on a student-centred basis. The curriculum is divided into three parts:

i) essential learning

ii) self-learning

iii) extra curriculum

Accordingly, the objective is to guide students towards a vocational education based on extra activities. It is mainly intended for years 1-11, or general education, according to Dr. Sedere, however, simultaneous change is necessary in both years 12-13 and in the university education system.

Dr. Sunil Jayantha Nawarathne, Director General of the National Institute of Education, writing in the same magazine, discusses the basis of the proposed amendments as follows:

“Our country has an education system that dates back two thousand five hundred years. This excellent education system was subjugated and lost with the expansion of the education system the British imposed upon us, leaving us with this British system by 1948. We have still been unable to establish a home-grown education system seventy -four years later, leading to multiple issues in the citizens who follow this education system. We need a new generation suited to the 21st century. To achieve this objective, the National Education Institute is introducing these new 2022 educational reforms with a national objective in mind. Creativity, innovation and entrepreneurial mindset are what we aim to achieve with this new education system.”

Let us examine what a productive citizen, fitting the 21st century looks like.

21st Century and 4th IR ready human capital

21 CHC = 3R + 3L + 2C + SDL

21 CHC – 21st Century-ready Human Capital

3R – Reading

wRiting

aRithmetic

3L – Learning skills

Literacy skills

Life skills

2C – Character development

Citizenship

SDL – Self-directed learner

He terms the current education system in Sri Lanka as a 3R system – (Reading, wRiting, aRithmetic). This does not include innovation or questioning the status quo. He accepts that advancement is not possible using the old system, when the reality is that we are now 22 years into the 21st century. “Even an old mobile phone does not meet the requirements of today. A Smart phone is now a necessity – for using the internet, photography, banking and many other activities are now carried out using the smart phone. To change the system to meet today’s needs, the 3R system needs further additions: 3L, 2C and SDL.

3L – Learning skills, Literacy skills, Life skills

2C – Character development, Citizenship

SDL – Self-directed learner

Opinion

Thoughts for Unduvap Poya

Unduvap Poya, which falls today, has great historical significance for Sri Lanka, as several important events occurred on that day but before looking into these, as the occasion demands, our first thought should be about impermanence. One of the cornerstones of Buddha’s teachings is impermanence and there is no better time to ponder over it than now, as the unfolding events of the unprecedented natural disaster exemplify it. Who would have imagined, even a few days ago, the scenes of total devastation we are witnessing now; vast swathes of the country under floodwaters due to torrential rain, multitudes of earth slips burying alive entire families with their hard-built properties and closing multiple trunk roads bringing the country to a virtual standstill. The best of human kindness is also amply demonstrated as many risk their own lives to help those in distress.

In the struggle of life, we are attached and accumulate many things, wanted and unwanted, including wealth overlooking the fact that all this could disappear in a flash, as happened to an unfortunate few during this calamitous time. Even the survivors, though they are happy that they survived, are left with anxiety, apprehension, and sorrow, all of which is due to attachment. We are attached to things because we fail to realise the importance of impermanence. If we do, we would be less attached and less affected. Realisation of the impermanent nature of everything is the first step towards ultimate detachment.

It was on a day like this that Arahant Bhikkhuni Sanghamitta arrived in Lanka Deepa bringing with her a sapling of the Sri Maha Bodhi tree under which Prince Siddhartha attained Enlightenment. She was sent by her father Emperor Ashoka, at the request of Arahant Mahinda who had arrived earlier and established Buddhism formally under the royal patronage of King Devanampiyatissa. With the very successful establishment of Bhikkhu Sasana, as there was a strong clamour for the establishment of Bhikkhuni Sasana as well, Arahant Mahinda requested his father to send his sister which was agreed to by Emperor Ashoka, though reluctantly as he would be losing two of his children. In fact, both served Lanka Deepa till their death, never returning to the country of their birth. Though Arahant Sanghamitta’s main mission was otherwise, her bringing a sapling of the Bo tree has left an indelible imprint in the annals of our history.

According to chronicles, King Devanampiyatissa planted the Bo sapling in Mahamevnawa Park in Anuradhapura in 288 BCE, which continues to thrive, making it the oldest living human planted tree in the world with a known planting date. It is a treasure that needs to be respected and protected at all costs. However, not so long ago it was nearly destroyed by the idiocy of worshippers who poured milk on the roots. Devotion clouding reality, they overlooked the fact that a tree needs water, not milk!

A monk developed a new practice of Bodhi Puja, which even today attracts droves of devotees and has become a ritual. This would have been the last thing the Buddha wanted! He expressed gratitude by gazing at the tree, which gave him shelter during the most crucial of times, for a week but did not want his followers to go around worshipping similar trees growing all over. Instead of following the path the Buddha laid for us, we seem keen on inventing new rituals to indulge in!

Arahant Sanghamitta achieved her prime objective by establishing the Bhikkhuni Sasana which thrived for nearly 1200 years till it fell into decline with the fall of the Anuradhapura kingdom. Unfortunately, during the Polonnaruwa period that followed the influence of Hinduism over Buddhism increased and some of the Buddhist values like equality of sexes and anti-casteism were lost. Subsequently, even the Bhikkhu Sasana went into decline. Higher ordination for Bhikkhus was re-established in 1753 CE with the visit of Upali Maha Thera from Siam which formed the basis of Siam Maha Nikaya. Upali Maha Thero is also credited with reorganising Kandy Esala Perahera to be the annual Procession of the Temple of Tooth, which was previously centred around the worship of deities, by getting a royal decree: “Henceforth Gods and men are to follow the Buddha”

In 1764 CE, Siyam Nikaya imposed a ‘Govigama and Radala’ exclusivity, disregarding a fundamental tenet of the Buddha, apparently in response to an order from the King! Fortunately, Buddhism was saved from the idiocy of Siyam Nikaya by the formation of Amarapura Nikaya in 1800 CE and Ramanna Nikaya in 1864 CE, higher ordination for both obtained from Burma. None of these Niakya’s showed any interest in the re-establishment of Bhikkhuni Sasana which was left to a band of interested and determined ladies.

My thoughts and admiration, on the day Bhikkhuni Sasana was originally established, go to these pioneers whose determination knew no bounds. They overcame enormous difficulties and obtained higher ordination from South Korea initially. Fortunately, Ven. Inamaluwe Sri Sumangala Thero, Maha Nayaka of Rangiri Dambulla Chapter of Siyam Maha Nikaya started offering higher ordination to Bhikkhunis in 1998 but state recognition became a sore point. When Venerable Welimada Dhammadinna Bhikkhuni was denied official recognition as a Bhikkhuni on her national identity card she filed action, with the support of Ven. Inamaluwe Sri Sumangala Thero. In a landmark majority judgement delivered on 16 June, the Supreme Court ruled that the fundamental rights of Ven. Dhammadinna were breached and also Bhikkhuni Sasana was re-established in Sri Lanka. As this judgement did not receive wide publicity, I wrote a piece titled “Buddhism, Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis” (The Island, 10 July 2025) and my wish for this Unduvap Poya is what I stated therein:

“The landmark legal battle won by Bhikkhunis is a victory for common sense more than anything else. I hope it will help Bhikkhuni Sasana flourish in Sri Lanka. The number of devotees inviting Bhikkhunis to religious functions is increasing. May Bhikkhunis receive the recognition they richly deserve.” May there be a rapid return to normalcy from the current tragic situation.”

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

Opinion

Royal Over Eighties

The gathering was actually of ‘Over Seventies’ but those of my generation present were mostly of the late eighties.

Even of them I shall mention only those whom I know at least by name. But, first, to those few of my years and older with whom speech was possible.

First among them, in more sense than one, was Nihal Seneviratne, at ninety-one probably the oldest present. There is no truth to the story that his state of crisp well-being is attributable to the consumption of gul-bunis in his school days. It is traceable rather to a life well lived. His practice of regular walks around the house and along the lane on which he lives may have contributed to his erect posture. As also to the total absence of a walking stick, a helper, or any other form of assistance as he walked into the Janaki hotel where this gathering took place.

Referencing the published accounts of his several decades-long service in Parliament as head of its administration, it would be moot to recall that his close friend and fellow lawyer, J E D Gooneratne, teased him in the following terms: “You will be a bloody clerk all your life”. He did join service as Second Assistant to the Clerk to the House and moved up, but the Clerk became the Secretary General. Regardless of such matters of nomenclature, it could be said that Nihal Seneviratne ran the show.

Others present included Dr. Ranjith de Silva, Surgeon, who was our cricket Captain and, to the best of my knowledge, has the distinction of never engaging in private practice.

The range of Dr. K L (Lochana) Gunaratne’s interests and his accomplishments within each are indeed remarkable. I would think that somebody who’d received his initial training at the AA School of Architecture in London would continue to have architecture as the foundation of his likes /dislikes. Such would also provide a road map to other pursuits whether immediately related to that field or not. That is evident in the leadership roles he has played in the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Town Planners among others. As I recall he has also addressed issues related to the Panadura Vadaya.

My memories of D L Seneviratne at school were associated with tennis. As happens, D L had launched his gift for writing over three decades ago with a history of tennis in Sri Lanka (1991). That is a game with which my acquaintance is limited to sending a couple of serves past his ear (not ‘tossing the ball across’ as he asked me to) while Jothilingam, long much missed, waited for his team mates to come for practices. It is a game at which my father spent much time both at the Railway sports club and at our home-town club. (By some kind of chance, I recovered just a week ago the ‘Fred de Saram Challenge Cup’ which, on his winning the Singles for the third time, Koo de Saram came over to the Kandana Club to hand over to him for keeps. They played an exhibition match which father won). D L would know whether or not, as I have heard, in an exhibition match in Colombo, Koo defeated Frank Sedgman, who was on his triumphant return home to Oz after he had won the Wimbledon tournament in London.

I had no idea that D L has written any books till my son brought home the one on the early history of Royal under Marsh and Boake, (both long-bearded young men in their twenties).

It includes a rich assortment of photographs of great value to those who are interested in the history of the Anglican segment of Christian missionary activity here in the context of its contribution to secondary school education. Among them is one of the school as it appeared on moving to Thurstan road from Mutwal. It has been extracted from the History of Royal, 1931, done by students (among whom a relative, Palitha Weeraman, had played a significant role).

As D L shows, (in contra-distinction to the Catholic schools) the CMS had engaged in a largely secular practice. Royal remained so through our time – when one could walk into the examination room and answer questions framed to test one’s knowledge of Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam; a knowledge derived mostly from the lectures delivered by an Old Boy at general assembly on Friday plus readings from the Dhammapada, the Bhagavad Gita, the St. John’s version of the Bible or the Koran recited by a student at senior assembly on Tuesday / Thursday.

D L’s history of Royal College had followed in 2006.

His writing is so rich in detail, so precise in formulation, that I would consider this brief note a simple prompt towards a publisher bringing out new editions at different levels of cost.

It was also a pleasure to meet Senaka Amarasinghe, as yet flaunting his Emperor profile, and among the principal organisers of this event.

The encounter with I S de Silva, distinguished attorney, who was on Galle road close to Janaki lane, where I lived then was indeed welcome. As was that with Upali Mendis, who carried out cataract surgery on my mother oh so long ago when he was head of the Eye Hospital. His older brother, L P, was probably the most gifted student in chemistry in our time.

Most serendipitous perhaps was meeting a son of one of our most popular teachers from the 1950s, – Connor Rajaratnam. His cons were a caution.

by Gamini Seneviratne

Opinion

“Regulatory Impact Assessment – Not a bureaucratic formality but essentially an advocacy tool for smarter governance”: A response

Having meticulously read and re-read the above article published in the opinion page of The Island on the 27 Nov, I hasten to make a critical review on the far-reaching proposal made by the co-authors, namely Professor Theekshana Suraweera, Chairman of the Sri Lanka Standards Institution and Dr. Prabath.C.Abeysiriwardana, Director of Ministry of Science and Technology

The aforesaid article provides a timely and compelling critique of Sri Lanka’s long-standing gaps in evidence-based policymaking and argues persuasively for the institutional adoption of Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA). In a context where policy missteps have led to severe economic and social consequences, the article functions as an essential wake-up call—highlighting RIA not as a bureaucratic formality but as a foundational tool for smarter governance.

One of the article’s strongest contributions is its clear explanation of how regulatory processes currently function in Sri Lanka: legislation is drafted with narrow legal scrutiny focused mainly on constitutional compliance, with little or no structured assessment of economic, social, cultural, or environmental impacts. The author strengthens this argument with well-chosen examples—the sudden ban on chemical fertilizer imports and the consequences of the 1956 Official Language Act—demonstrating how untested regulation can have far-reaching negative outcomes. These cases effectively illustrate the dangers of ad hoc policymaking and underscore the need for a formal review mechanism.

The article also succeeds in demystifying RIA by outlining its core steps—problem definition, option analysis, impact assessment, stakeholder consultation, and post-implementation review. This breakdown makes it clear that RIA is not merely a Western ideal but a practical, structured, and replicable process that could greatly improve policymaking in Sri Lanka. The references to international best practices (such as the role of OIRA in the United States) lend credibility and global context, showing that RIA is not experimental but an established standard in advanced governance systems.

However, the article could have further strengthened its critique by addressing the political economy of reform: the structural incentives, institutional resistance, and political culture that have historically obstructed such tools in Sri Lanka. While the challenges of data availability, quantification, and political pressure are briefly mentioned, a deeper analysis of why evidence-based policymaking has not taken root—and how to overcome these systemic barriers—would have offered greater practical value.

Another potential enhancement would be the inclusion of local micro-level examples where smaller-scale regulations backfired due to insufficient appraisal. This would help illustrate that the problem is not limited to headline-making policy failures but affects governance at every level.

Despite these minor limitations, the article is highly effective as an advocacy piece. It makes a strong case that RIA could transform Sri Lanka’s regulatory landscape by institutionalizing foresight, transparency, and accountability. Its emphasis on aligning RIA with ongoing national initiatives—particularly the strengthening of the National Quality Infrastructure—demonstrates both pragmatism and strategic vision.

At a time, when Chairmen of statutory bodies appointed by the NPP government play a passive voice, the candid opinion expressed by the CEO of SLSI on the necessity of a Regulatory Impact Assessment is an important and insightful contribution. It highlights a critical missing link in Sri Lanka’s policy environment and provides a clear call to action. If widely circulated and taken seriously by policymakers, academics, and civil society, it could indeed become the eye-opener needed to push Sri Lanka toward more rational, responsible, and future-ready governance.

J. A. A. S. Ranasinghe,

Productivity Specialty and Management Consultant

(rathula49@gmail.com)

-

News5 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoUpdated Payment Instructions for Disaster Relief Contributions

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth