Features

COVID-19 Pandemic in Sri Lanka: Contextualizing it geographically – Part I

By Dr. Nalani Hennayake and

Dr. Kumuduni Kumarihamy

Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya

The emergence of a second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was inevitable, although the sudden outbreak in Minuwangoda took us by surprise. We now see that it is steadily spreading outside of Colombo. The districts of Nuwara-Eliya and, Trincomalee have been declared as areas not suitable for tourist activities, and pilgrimage to Sri Pada is discouraged. Kandy, where we live is the fourth district in terms of the total number of COVID-19 positive cases detected. The actual reality of the COVID-19 pandemic, changing nature of the virus, how many are infected, detected, tested, and identified as infectious, where they live, work, and move around, could be far beyond what statistics and dashboards may reveal.

Along with the health and security personnel, the government successfully managed the first wave with a series of controlling strategies from travel restrictions, imposed quarantines, self, and institutional isolations. Interestingly, all such strategies, have been territorial or spatial measures. In other words, the management of the COVID-19 pandemic requires a set of spatial strategies that affect human spatial behaviour, relations, and attitudes. Inspired by this, in this article, we  embark upon a project of contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka, geographically. This article aims to show the significance of a geographical framework of thinking, with limited data and information. In other words, what we present here is a sample of what can be done if the data are available at the GN division level. Such an analysis would demonstrate how geography is an innately central character of how COVID-19 is spread, dealt with, and, most importantly, in an academic perspective, in representing, analyzing, and understanding the present situation and future scenarios of the pandemic.

embark upon a project of contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka, geographically. This article aims to show the significance of a geographical framework of thinking, with limited data and information. In other words, what we present here is a sample of what can be done if the data are available at the GN division level. Such an analysis would demonstrate how geography is an innately central character of how COVID-19 is spread, dealt with, and, most importantly, in an academic perspective, in representing, analyzing, and understanding the present situation and future scenarios of the pandemic.

Current situation: What is reported, recorded, and represented?

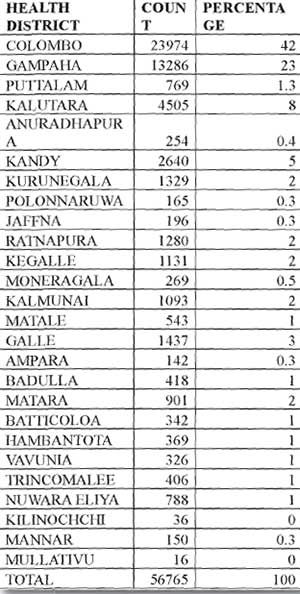

In its Situation Report on February 3, 2021, the Epidemiology Unit at the Ministry of Health reports 65,698 as ‘the total number confirmed’ and 59,883 as ‘the total number recovered’ COVID-19 cases. Thus, we have only 5485 patients as confirmed and hospitalized, with 548 added as suspected and hospitalized patients. The other basic information provided on this website is the district-wise and hospital-wise distribution of the total number of confirmed patients. The highest number of COVID-19 patients, nearly about 42 percent, comes from the Colombo district, while Gampaha and Kalutara record respectively about 23 and 8 percent (see Table 01) Nuwara-Eliya-Ratnapura. The number of COVID-19 infected seems to increase in the districts of Kandy, Kurunegala, Puttalam, Nuwaraeliya, Rathnapura, Kegalle, Galle, Badulla, and Kalmunai.

Table 01: District Distribution of Confirmed Patients (as of February 3, 2021 -10 a.m, Situation Report)

Note:

Considered only the individuals who contracted the disease from the districts

How the COVID-19 pandemic is reported and represented in the media and various sources is all the more confusing. The statistics coupled with the newscasters’ tone (depending on which channel you watch the news in the evening) determine the outbreak’s nature for the day. Frequently, in the middle of the regular news reporting, we hear, “Here we received some new information right now” – new COVID-19 cases added – leaving us with a sense of uncertainty as to how this coronavirus proliferate daily. Generally, during the first wave, the media played a crucial role in raising awareness about the COVID-19 pandemic and sensitizing the people towards the situation with their frequent announcements and reminders. Such an effort is not noticeable during the second wave. Perhaps, the ‘new normal’ has become normal. The new cases are generally attributed to the four clusters. As of February, 2021, the Minuwangoda cluster has proliferated up to 61,705 cases, as it is reported on the relevant official websites. At different phases of the second wave, Peliyagoda and Prison clusters were also added to the Minuwangoda cluster. In the popular memory, informed by the official line and the format of reporting by various channels and mainstream media, such reporting creates an impression that it is still the Minuwangoda/Peliyagoda cluster that is expanding as if it has not yet spread to other parts of the country.

The first wave of the outbreak that began with the case of the Chinese tourist and lasted until almost late April 2020 was well controlled before the general election, through strategies such as physical distancing, quarantine, contact tracing (social, temporal, and spatial), lockdown, and isolation of villages and communities and travel restrictions. The first wave witnessed that restricting and controlling human spatial conduct and mobility are the determinants of preventing further transmission of the coronavirus. The government took strict measures to control human spatial mobilities through curfew and prolonged lockdowns at the provincial and, at times, even at the national level. It is reasonable to say that controlling human spatial mobilities has been a successful strategy in curtailing the first wave, enhanced by the commitment and dedication of the health, security, and various other sectors. However, during this first wave, the coronavirus carriers were identified as foreigners of two kinds instead of locals. They are the immigrant workers who had returned from the Middle East and Italy and a small number of actual foreigners visiting Sri Lanka. The exception to this was the Welisara Navy outbreak and small groups of the infected in a few low-income localities in Colombo. Thus, the coronavirus had not fortunately been ‘socialized’ into the local society.

At present, the second wave that began in early October, when an employee from a garment factory in Minuwangoda was found positive for COVID-19, is different. Although it was debated in the early days whether the coronavirus had still come through ‘foreigners,’ it is clear that the virus is, by now, ‘indigenous‘ to us. It took a while to acknowledge that the coronavirus is ‘socialized‘ – meaning that it is out there with us. It is imperative to know the geographical spread of the COVID-19. This is important for the decision-makers to enact necessary controlling mechanisms (i.e., isolation, lockdown, inter-regional restrictions on mobility, etc.) in the relevant regions, places, and localities on the one hand, and on the other, for the individual citizens to safeguard themselves from the coronavirus and to prevent its further transmission. Looking at the COVID-19 pandemic geographically is far beyond a simple exercise of mapping where the COVID-19 cases are found and located. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the geography of the world. Under pre-pandemic normalcy, spatial and geographic barriers are removed within the capitalist system to facilitate a smooth expansion and circulation of capital and commodity markets. The resultant flat geographical surface is what made the globalization of the COVID-19 pandemic possible. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed this as the countries resort to spatial and geographical restrictions (lockdown areas, restricted mobilities, isolated villages, high- risk, low-risk areas, etc.) to control the pandemic. Thus, we must contextualize and unravel the geographical dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic to gauge its extent, scope, and severity and reevaluate the efficacy of the controlling strategies and problematize it further.

Geographical contextualizing of the pandemic

Contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka would involve a range of geographical inquiries, analysis, and interpretation that spans from a simple mapping exercise to analyses of socio-cultural, economic, and political dynamics of the communities/ localities where the infected are detected. Geographers’ holistic and integrative perspective allows any phenomenon to be viewed in an interdisciplinary manner and a synthesized form. A geographical line of inquiry, on the one hand, enables the decision-makers to foresee and plan for the future scenarios in terms of, especially, risk areas (for containing the COVID-19 as well recovering the economy) and also to implement the controlling strategies more efficaciously and in a socially more responsible manner. On the other hand, such an exercise helps the public to understand the extent, scope, and severity of the crisis and to reflect individually upon the ethics of personal conduct necessary to prevent the further social proliferation of the coronavirus. Here we use the three themes of infection, vulnerability, and immunization to focus on COVID-19 in Sri Lanka geographically; out of seven themes (infection, vulnerability, resilience, blame, immunization, interdependence, and care) introduced in the Editorial, the Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (volume 45 of 2020). In addition, we introduce ‘social distancing’ as a form of micro-geography of COVID-19 since it enfolds a set of human spatial interactions involving spatial distancing at the individual level.

Geographies of infection

: With the first wave, particular places, except for Atalugama and a few low-income localities in Colombo were not identified with COVID-19. A majority of the infected were detected from those retained at the quarantine centres. Now, with the second wave, it is different. The questions of where the infected have been found, where they live, where they have been, and what kind of neighborhoods they have been found from are critical information relating to the transmission and control of COVID-19. At the global level, universities, research institutes, and various geo-visualization sites have produced maps demonstrating the global nature of COVID-19. They are mapped not only at the national scale but also covering the regional and local scales. In these global maps, Sri Lanka was earlier highlighted as a country that managed to control the COVID-19 successfully in the first wave with an insignificant number of fatalities. With the second wave, we are now reported as “at peak and rising at a rate of 16 infected per 100K people during ‘the last seven days’ (See the REUTERS COVID-19 TRACKER). Sri Lanka is classified as a country at 75% of the peak of the infection curve with a daily average of 523 new infections. In these global analyses, Sri Lanka places itself at the lowest end, compared globally and within Asia and the Middle East, regarding the total infections, deaths, average daily reported, and total per population. The relatively low position of the country’s outbreak in its region and the world should not be used, especially by the politicians, to downplay its severity at the national level. It is interesting to note that most of the news channels, immediately after reporting the outbreak’s national situation, instantly turn to the pandemic’s global standing, highlighting its severity, almost making the Sri Lankan situation, so to say, uneventful and insignificant. The politicians often tend to overemphasize this as a GLOBAL pandemic to escape from criticisms and lessen its significance at the national level.

(To be continued)

Features

Tree planting along road reservations and banks of streams

Reservations of Roads & Natural Streams which extend to about 10 to 20 on either side are not actively protected in Sri Lanka though it is very common in other countries. Those reservations are owned by the government. Therefore, public use of this land can be considered as a fair use of the land. Main purpose of this proposal is to introduce an intervention to connect the Forest Patches in urban areas such as Gampaha using the reservations of roads and natural streams, by planting trees so that those strips could also act as Urban Bio Corridors while enhancing the tree cover at national level. These trees also absorb the fumes emitted by vehicles while addressing global warming caused due to lack of tree cover. It also serves as a roof top for pedestrians who use reservations along public roads while adding aesthetic value to the area. Enhancing the community awareness about BioDiversity of Sri Lanka and the importance of maintaining a clean environment along road reservations is also another objective of this type of intervention. This intervention also addresses the needs of all sectors of the local communities.

Concept

The Green Road is a relatively new concept for roadway design that integrates transportation functionality and ecological sustainability. This project addresses the transport sector also because it facilitates Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) for local people. Therefore, Provincial Road Development Authority (PRDA) is the ideal institute to implement this project. It is also possible to introduce cycle tracks along stream banks as short cuts by improving the banks of natural streams as roads. This intervention would reduce vehicle congestion in main public roads while supporting Clean Sri Lanka programme because local communities themselves become watch dogs against culprits who pollute road reservations and water bodies of natural streams.

Already implemented projects in Mahaweli Areas

In Sri Lanka, the concept of Bio Corridor was introduced in 1988 under a Project called Mahaweli Agriculture and Rural Development project implemented in System B under an USAID funded programme. Similar to highways which connect main cities, in this case the Bio Corridors were introduced as “Bio Highways” connecting fragmented forest patches (“Bio Cities”) in paddy field areas. At the same time those corridors were improved as Cycle Tracks for the local farmers.

Figure 1 indicates the present status of a tree plantation programme implemented in Mahaweli Area (Thambuttegama) in the 1980s along newly introduced roads.

Past Experience of PRDA (WP) related to similar interventions

In 2010, similar intervention was introduced in Gampaha District in parallel with a flood mitigation project implemented by the Provincial Road Development Authority (WP). For example, while Uruwal Oya running adjacent to Gampaha Urban Area was improved to mitigate floods, riparian tree belt areas were also introduced. Later, parts of that stream running adjacent to Gampaha Town were improved as Recreational purposes such as jogging tracks for urban communities. As an additional benefit, it was expected that the shades provided by riparian tree cover would discourage growth of invasive plants such as Japan Jabara, which clogs the drainage outlets resulting in floods in urban areas.

by Eng. Mahinda Panapitiya

Features

Has Compass lost direction?

Sri Lankan voters have excelled in the art of changing governments in executioner style, which they did in many elections including that of 1977,1994, 2015, 2019 and, of course, 2024. They did so, giving massive majorities to parties in opposition that had only a few seats, because the preceding governments were so unpopular. It invariably was a negative vote, not a positive vote-endorsing policies, if any, of the incoming governments, the last election being no exception. NPP, contesting under the compass symbol, was essentially a revamp of the JVP and their main strategy, devoid of any specific policies, was throwing mud at opponents and promising a transparent, corruption free government. They made numerous promises on the hoof. Have they stood up to the challenges?

What the vast majority of the public wanted was a significant reduction in the cost of living, which has spiralled out of control due to the misdeeds of the many preceding regimes, resulting in near starvation for many. The NPP promised to renegotiate the deal with the IMF to give relief to the masses but soon found, to their dismay, that it was a non-starter. Of course, the supporters portrayed it as a display of pragmatism! They promised that the price of fuel could be slashed overnight as it was jacked up by the commission earned by the previous minister who was accused of earning over Rs 100 for every litre! It has not happened and the previous minister has not received the apology he deserves. The cost of living remains unbearable and all that the government continues to do effectively is slinging mud at opponents.

To the credit of the NPP government, financial corruption has not set in, but it cannot be forgotten that most previous governments, too, started this way, corruption setting in later in the cycle of government. However, corruption in other forms persist contrary to the promises made. Had the government sacked the former speaker, the moment he could not justify the claimed PhD, it could have claimed high ground and demonstrated that it would not tolerate corruption in any form. For some reason, unknown to the public, he seems to have a strong hold on the party and he seems indispensable!

As for bringing to justice those previously corrupt, only baby steps have been taken. During the election campaigns AKD promised to get Arjun Mahendran from Singapore within 24 hours of his election and now they are blaming the Singapore government! It looks as if promises were made without any idea as to the practicality of implementation. According to social media posts circulated, the list of assets held by Rajapaksas would have made them richer than Elon Musk! A lady lawyer who described in detail, during the election campaign, the wealth amassed in Uganda by Rajapaksas admitted, after her election, that there was no basis. Her justification was that the NPP government ensured free speech; even to tell lies as the truth.” Government media spokesman has just admitted that she lied about the cost of new year text messages sent by previous presidents and she remains an ‘honourable’ MP!

As far as transparency is concerned, Compass is directionless. MoUs/Pacts signed with India, during the recent visit of PM Modi shines bright with opaqueness! After giving various excuses previously, including that those interested could obtain details by making requests under the Right to Information Act, the official cabinet spokesman’s latest is that it needs the permission of India to release details. This makes one wonder whether there is a lot to hide or it may be that, de facto, we are already under the central government of India and that AKD is just the Chief Minister of the 29th state!

Whilst accusing the predecessors of misuse of power, the NPP does the same thing. AKD’s statements that he would be scrutinizing allocation of funds to local bodies, if opposition parties are elected, surely is an indirect threat to voters. Perhaps, it is not an election offence as the Elections Commission has not taken any action despite complaints!

Whether the exposition of the Tooth Relic, which was done in a mighty hurry, to coincide with the mini-election campaign would backfire remains to be seen. As it was done in a hurry, there was no proper planning and even the basic amenities were not provided to the thousands who queued for days. AKD, as usual, was quick with a political gesture by the unplanned visit meeting those in the queue. What he and his government should have done is proper planning but, instead, government supporters are inundating social media blaming the public for bad behaviour!

To cap this all is the biggest faux pas of all; naming the mastermind of the Easter Sunday attack. AKD built up expectations, and the nation was waiting for the exposure on 21 April, which never materialised. His acolytes are doling out excuses. Dr Nalinda Jayatissa was as evasive as possible during his post-cabinet meeting briefing. Perhaps, there is no mastermind other than those identified by all previous investigations including that by the FBI. All that the president did was handing over the Presidential Commission of Inquiry report to the CID. The acting IGP appointed a committee of three to study, but the next day a fourth person was added, a person who is named as one of those who did not act on intelligence received!

Perhaps, as an attempt to give credence to the allegations made in the Channel 4 programme, Pillayan was arrested. Though it was on a different offence, the alleged abduction of the former chancellor of the Eastern University, Minister Wijepala had the audacity to state in the parliament otherwise. Pillayan has been detained under the PTA, which the NPP promised to abolish! The worst is the campaign of character assassination of Udaya Gammanpila who has decided to represent Pillayan. Dr Jayatissa, who has never practised his profession, took exception that Gammanpila, who has not practiced as a lawyer, is representing Pillayan. Gammanpila has corrected him by listing the cases he had been involved in. In any case, Gammanpila need not be in court but get a set of lawyers to defend, if and when, a case is filed. It begs clarification, the ministerial comment that Gammanpila should be ashamed to represent Pillayan! Has the government already decided the guilt of Pillayan?

Compass has lost direction, indeed, and far too soon!

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

Features

Canada holds its own as Americans sour on Trump

On Monday, April 28, Canadians gave the Liberal Party its fourth successive mandate, albeit as another Minority Government but much stronger than in the last two elections, and, more importantly, with a different Prime Minister. Justin Trudeau who had been Prime Minister from 2015 was forced to resign in January 2025 on account of his perceived electoral unpopularity. Trudeau was succeeded by Marc Carney, 60 year old former Governor of the Bank of Canada and later the Bank of England, who dramatically revived the falling fortunes of the Liberal Party and secured its fourth mandate in 10 years.

The Liberal Party and Prime Minister Mark Carney owe their good fortunes to the presidential madness that is going on south of the border, in the United States of America. With his mercurial obsession over tariff’s and recurrent musings about making Canada America’s 51st State, President Trump painted the backdrop to the Canadian election. Trump’s antics did not go down well with the Canadian public and in a rare burst of patriotism the people of Canada overarched their diversities of geography, language, culture, religion and ethnicity, and rallied round the Maple Leaf national flag with utmost determination to stick it to Trump and other Ugly Americans of his ilk.

People and businesses in Canada shunned American products, stopped travelling to US holiday destinations and even took to booing the US national anthem at sporting events involving US and Canadian teams. The threat of economic pain due to a tariff war is real, but Canadians are daring to suffer pain rather than become a part of the US. And Justin Trudeau showed his best leadership in his last days as Prime Minister. Combining diplomatic skill and splendid teamwork with eloquent defiance, Trudeau succeeded in forcing Trump into what has since become Trump’s modus operandi in implementing his idiosyncratic tariff policy: tariff, one day; pause, the next day; and uncertainty, extended indefinitely.

100 Days of Disaster

What he began with Canada and Mexico, Trump has since writ large upon the whole world. His second term is already a term of chaos not only for America but also for the whole world economy. The US economy is officially in first quarter contraction. Another four months, it could be a man made recession of what was in January an economy that was humming sound and was easily the best performing one in the world. It’s only 100 days of the second term, and what is left of it is looming as eternity. “Only 1,361 Days to Go,” is the cover page heading of the latest issue of the Economist. That sums up America’s current state of affairs and their global spillover effects.

Americans are beginning to sour on Trump but there is no way for them to channel their frustrations and anger to force an immediate executive retreat. Trump has reduced the Republican Party to be his personal poodle and with Republics holding slender majorities in both the Congress and the Senate, the Legislative Branch of the US is now wholly beholden its Executive. The traditional wait is for the midterm Congress elections in two years. But Trump has no respect for traditions and conventions, and it would be two years too much before a Democratic majority in the two houses could bestir the Congress to check and balance the runway president.

The Judicial Branch is now playing catch up after the Supreme Court had given Trump near absolute immunity and enabled his second coming. The lower courts are applying the law as they should and stymieing Trump’s palpably illegal orders on everything from deporting immigrants, to downsizing government, and gutting the country’s university system. The tariff cases are slowly making their way to courts and they will add more confusion to the running of the economy before some kind of sanity is restored. Overall, by upending a system of government that has been constitutionally evolving over 200 years, Trump is providing a negatively sobering demonstration that no system is foolproof if a capable fool is elected to take over the reins of government.

Fortunately for the world, other governments and polities have been quick in drawing the right lessons from the demonstration effects of Trump on their American cousins. Trump’s excesses have had a dampening effect on right wing populism in other countries. The Canadian elections are one such demonstration. Another is expected in Australia where national elections are scheduled for Saturday, May 3. In Europe, right wing populist parties are scaling down their rhetoric to avoid facing local backlashes to Trump’s American excesses.

No populist leader anywhere wants to go where Trump is blindly heading, and no one is mad enough like him to think that imposing tariffs is the way to grow a national economy. In Hungary, its strongman Viktor Orbán after securing super majorities in four elections since 2010, is facing the real possibility of defeat in the national elections next year. Orban is regressively anti-Eu while 86% of Hungarians want to strengthen their EU ties, and they are naturally getting tired of Orban’s smearing of the EU just like all Europeans are getting tired of Trump’s and his VP Vance’s anti-European rhetoric.

Canada Holds its Own

Canada, despite its proximity to the US, has never been a haven for Trump’s right wing populism. Yet there have always been and continue to be pockets of support for Trumpism in Canada, and they have found their sanctuary within the Conservative Party of Canada and behind its leader Pierre Poilievre, a 45-year old career politician who entered parliament in 2005 at the age of 25 and became Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition 18 years later, in 2023.

Clever and articulate with an ability to spin rhyming simplistic slogans, Poilievre cultivated his political base by feeding it on a diet of vitriolic and vulgar personal attacks and advertisements denigrating then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Poilievre identified himself with the 2022 truck convoy protest that stormed Ottawa, cheered on by MAGA America, and he came to be seen as Canada’s Trump-lite (not unlike Peter Dutton, the Leader of the Opposition in Australia). Nonetheless, Poilievre’s attacks on Trudeau worked in the post-Covid climate of economic hardships and Trudeau’s popularity sank to the point that his own MP’s started calling for his resignation.

Alas for Poilievre, Trudeau’s resignation in January took away the one political foil or bogeyman on whom he had built his whole campaign. In addition, while his attacks on Trudeau diminished Trudeau’s popularity, it did not help enhance Mr. Poilievre’s image among Canadians in general. In fact, he was quite unpopular outside his base of devotees. More people viewed him unfavourably than those who viewed him favourably. Outside his base, he became a drag on his party. He would even go down to defeat in his own electorate and lose his seat in parliament that he had held for 20 years.

Mr. Poilievre’s troubles began with the emergence of Mark Carney as the new Liberal Leader and Prime Minister – looking calm, competent and carrying the ideal resume of experience in dealing with the 2008 financial crisis as Governor of the Bank of Canada, and calming market nerves after the 2016 Brexit referendum as Governor of the Bank of England. Carnie, who had never been in formal politics before, seemed the perfect man to be Prime Minister to weather the economic uncertainties that President Trump was spewing from Washington. Almost overnight Liberal fortunes shot up and after resigning themselves to face a crushing defeat with Trudeau at the helm, Liberals were suddenly facing real prospects of forming a majority after two terms of minority government.

In the end, thanks to the quirky genius of the electorate, Liberals ended with 168 seats with 43.7% of the vote, and four seats short of a majority in the 343 seat national parliament, while the Conservative Party garnered 144 seats with 41.3% vote share. Both parties gained seats from their last election tallies, 15 new seats for Liberals and 16 for Tories, and, unusual in recent elections, the two parties garnered 85% of the total vote. The increases came at the expense of the two smaller but significant parties, the left leaning New Democratic Party (reduced from 24 to seven seats); and the Bloc Québécois (reduced from 45 to 23 seats) that contests only in the French majority Province of Quebec. The Green Party that had two MPs lost one of them in the election.

In the last parliament, the New Democrats gave parliamentary support to the minority Trudeau government in return for launching three significant social welfare initiatives – a national childcare program, an income-based universal dental care program, and a pharmacare program to subsidize the cost of prescription drugs. These are in addition to the system of universal public health insurance for hospitals and physician services that has been in place from 1966, thanks again to the programmatic insistence of the New Democratic Party (NDP).

But the NDP could not reap any electoral reward for its progressive conscience and even its leader Jagmeet Singh, a Sikh Canadian, lost his seat in the election. The misfortune of the NDP and the Bloc Québécois came about because even their supporters like many other Canadians wanted to entrust Mark Carney, and not Pierre Poilievre, with the responsibility to protect the Canadian economy from the reckless onslaughts of Donald Trump.

Yet, despite initial indications of a majority government, the Liberals fell agonizingly short of the target by a mere four seats. The Tories, while totally deprived of what seemed in January to be the chance of a landslide victory, managed to stave off a Liberal sweep under Mark Carney. The answers to these paradoxes are manifold and are part of the of reasonably positive functioning of Canadian federalism. The system enables political energies and conflicts to be dispersed at multiple levels of government and spatial jurisdictions, and to be addressed with minimal antagonism between contending forces. The proximity to the US helps inasmuch as it provides a demonstration of the American pitfalls that others should avoid.

by Rajan Philips

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoJapan-funded anti-corruption project launched again

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSethmi Premadasa youngest Sri Lankan to perform at world-renowned Musikverein in Vienna

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOTRFU Beach Tag Rugby Carnival on 24th May at Port City Colombo

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoNational Savings Bank appoints Ajith Akmeemana,Chief Financial Officer

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTrump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular