Features

Combination of circumstances gives CBK the opportunity to dissolve Parliament

Bradman takes final bow after a period on intense political manoeuvering

Ranil’s strength, according to the Constitution, came from his supremacy in Parliament. With great managerial skill he managed to keep at all times a sizable majority in place. The UNF never lost a vote in Parliament during those two years (Ranil was PM). The UNF itself was a coalition bringing together five parties which contested the election together. It must have brought much credit to his political acumen and management skills that in spite of severe stresses and strains, the UNF held together. It was also quite remarkable in a country where party political loyalties are notably fickle, that during the period of his government there was not a single resignation from party or office.

According to the Constitution, Parliament cannot be dissolved by presidential fiat until one year after its election. Thereafter though, the president is vested with the power to dissolve parliament at will and even though the government might have an absolute majority in the House. When Ranil’s second year began there was the opportunity for a sudden dissolution but although fears were raised from time to time, this did not happen. The peace process was well on track, the economy was beginning to pick up and investor confidence was rising. It needed an event of dramatic consequence to trigger any decision by the president to dissolve Parliament.

The opportunity finally came through a combination of circumstances. Firstly, the negotiation process itself had stalled in April 2003. Citing non-performance of undertakings given at the `talks’ as a primary reason, and the Washington donor review meeting to which they had not being invited as another, the LTTE refused to continue the schedule of talks as planned. Worse was to follow when they declined the invitation to participate at the June Tokyo Donor Conference. Initially the donor meeting had been planned for with both the government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE being joint hosts.

There was a final issue which literally broke the camel’s back and impelled the line of action that resulted in the dissolution of Parliament.

The Interim Self-Governing Authority (ISGA)

ISGA was the response of the LTTE to the government’s proposals for an Interim Administration for the northeast. The government, after a great deal of thought by Ranil and G L, had sent in a proposal in June 2003 basically designed to provide for a mechanism which would handle effectively and speedily the donor funding anticipated for development. The decision-making authority was to consist of LTTE and government nominees (including representatives of the Muslims) with the LTTE having the majority.

The concept of an interim administration for the northeast was a cornerstone of the road map for a durable peace and had been one of Ranil’s undertakings in the election manifesto for the 2001 elections. Of course the details had not been determined and the government proposals at this stage were in the nature of a first offer open for discussions.

After a while, on October 31, 2003 the LTTE predictably, in view of their own thinking on the matter which was to obtain control of the administration of the northeast province, and not merely have a mechanism for the funding component, put forward their proposals for an Interim Self-Governing Authority (ISGA). This was clearly very far forward towards autonomy in the management of the northeast.

Ranil and G L responded immediately that the ISGA went further than they would think necessary at this stage of the negotiations but that the proposals could certainly constitute the basis for further discussion.

However considerable fear began to be expressed in the media, fuelled by elements opposed to the peace process and the political opposition to the government, that the ISGA represented the opening towards the creation of Eelam. The public debate and agitation put the UNF, already reeling from a sustained campaign carried out by the media, on the defensive. The media had a ready-made portfolio of apparent concessions made by the government to the LTTE through its ‘so-called’ peace process and supposed imminent danger to national security, especially the sea base at Trincomalee through the surreptitious establishment of 13 camps encircling the town.

Daily dispatches from intrepid news reporters filled the newspapers and the names of the ‘formidable’ LTTE camps, particularly Manirasakulam, were in everyone’s heads. Finally a brave attempt at taking the camp by a force of volunteers led by the leader of the Hela Urumaya was foiled in the nick of time – the army turning the force back before they could get within firing range. The government – defence ministry response – was lacklustre and the media had succeeded in preparing the grounds for a final denouement.

The president timed her move to perfection. On November 4, 2003 catching the ground-swell against the government at full tide and at a time when Ranil was out of the country in Washington, for a meeting with President Bush about the Free Trade Agreement with the US, President Chandrika launched her strike. She took over, under her constitutional powers, the ministry of defence on the grounds of the imminent threat to national security.

To make a clean sweep of things she also added the ministry of interior, which controlled the police, and the ministry of mass communication which ran the media institutions – two TV stations with all island coverage, the radio broadcasting service and Lake House with its complement of daily English, Sinhala and Tamil newspapers. This was a huge and an important capture of state power by the president which completely altered the balance of power in the cohabitation arrangement of December 2001. “A superbly timed and effectively executed constitutional coup,” as some commentators described it.

UNP Regroups after November 4

I had not gone to Washington with the PM because the trip was to be of very short duration. It was a long journey and I decided to stay back. As soon as the news broke, Karu Jayasuriya who was deputising for Ranil and Malik Samarawickrama, the very active chairman of the party, got together and called the rest of the Cabinet and MPs for an urgent meeting at Temple Trees. The mood was ugly. Some were for taking to the streets and creating a public agitation which would engulf the president’s house. Finally someone got through to Ranil – it was 3.00 am in the morning in Washington – but he was soon wide awake and giving instructions on how the crisis was to be met.

There was to be no panic reaction and no thought of violence. We were to be in constant consultation with him as the matter progressed. Tilak Marapana, minister of defence, John Amaratunga, minister of the interior and (media minister) Imtiaz Bakeer Markar should go about their work as if nothing had happened. The UNF parliamentary majority should be preserved at all costs. Ranil displayed great maturity in the way he dealt with this crisis. Nothing should be done to disturb the peace; the government should act with care; law and order should be preserved at all times and we should wait until he returned as scheduled. He would come back not a day earlier not a day later.

Ranil’s return to Colombo by air that morning, the November 7, was unprecedented. I have never seen a display of public support as that which he received from the hundreds of thousands who converged on the Katunayake-Colombo highway that day. The crowd was hysterical and would not let the convoy of cars pass on. One could, and some did, walk the 22 kilometres to Colombo faster than the cavalcade of cars. The triumphal procession (it had now taken on the character of a victory parade with papara music bands in open trucks providing the sound) took over nine hours. He should have been at Temple Trees at 10.00 am. He arrived at 5.30 pm flushed and hoarse with the number of speeches he had made on route but exultant in the outpouring of public support he had seen and felt that day.

The National Government of Reconciliation and Reconstruction

Ranil awaited the next move from the president. It came in the form of an invitation to talk. Ranil asked me to join him and I accepted with alacrity because it was always a pleasure to meet Chandrika. She would immediately remember the old days when I was her father’s and mother’s secretary and I felt very much at home with her. She had Karunaratne, her secretary and Mano Tittawella, who had come in as senior advisor at the presidential secretariat on her side.

The little communique we issued later said it was a cordial meeting which lasted almost two hours. But it was much more exciting than that. It began with the tension we officials feared. Ranil’s opening ball was a bumper. “Why did you have to do this when I was away?” he started off with. President Chandrika went into a very interesting, very long explanation of all that the UNP had done to her in the past two years. She had suffered all this in silence. But she had to act now since the government’s inaction had placed the nation in jeopardy. So she had to take over defence.

However she wanted Ranil to continue with the peace process. She did not want to touch it. Ranil countered that it was impossible to handle the peace process without control of the ministry of defence. If she could not give him back the ministry of defence then he had no objection at all to her handling the peace process. As the ‘ping-pong’ match was looking like ending in a draw the president made it known that she was suggesting this in the context of her overall design of a national government which could be termed one for “reconciliation and reconstruction”.

All parties would be represented in it; they could draw up a common, agreed-upon, program of action covering the national issues peace process, constitutional reform, economic development and governance questions; the Cabinet could be expanded from 50 upwards if necessary and there would be a definite period of time for the national government. At the end of the one or two-year period the need for the national government would not be there and the parties could go their individual ways.

President Chandrika also hinted that if this did not find acceptance she had other options to proceed with on her own. She indicated that there was a strong movement from within the PA for an alliance – a sandhanaya – with the JVP. That particular agreement was almost ready for signature. So the idea of a national government was now beginning to sound politically interesting and doable, albeit with a lot of goodwill on all sides. The small print had however to be worked out.

For that, both the president and Ranil agreed, one needed persons who were not politicians. Finally it was decided that the respective secretaries, that is Karu (Jayasuriya) and myself and Malik Samarawickrem and Mano Tittawella would be the four-man team who would work out the details. The president liked and got on well with Malik and she suggested he come in as Ranil’s representative while she would have Mano Tittawella as her person on the team.

Thus was born the ‘Mano-Malik Talks’ – an adequate sobriquet manufactured by the media for the seven rounds of a fascinating, extended conversation between the four of us in the months of November and December 2003 and January 2004. It was valid too, since it was the two of them who did most of the talking. Karu and I did the writing.

We had two basic terms of reference. The first which was easy was to formulate a consensual plan of action outlining the detailed measures to be taken on which all could agree. This covered steps to be taken to resume the negotiations with the LTTE, areas of governance like the appointment of the anti-bribery commission, electoral reform – the Report of the Select Committee of Parliament was to be expedited, clearing the impasse regarding the setting up of the elections commission, and a listing of urgent infrastructural projects awaiting development – roads, power plants, port facilities, etc.

The second which was extremely complex and on which no agreement could be reached, was the issue of the defence ministry. The critical question being as to whether there was any formula by which Ranil would be able to assume authority over the defence apparatus which would enable him to pursue the peace process, while the defence ministry portfolio would continue to be handled by the president. Try as we could, and we had some suggestions from a friendly neighbour too, there was no way something acceptable to both chief actors could be devised all through November and December.

Time was running out when we resumed our talks after the long X’mas and New Year break. We managed to cobble together a not-so-satisfactory arrangement which would have needed great patience and forbearance by both the president and prime minister to work through at our final meeting at the end of January. Malik and I were promised a final decision by the other side at a scheduled meeting on February 9 after the Independence Day festivities were completed. The presidential message of February 4 too seemed promising. But then inexplicably, on the night of February 7, Parliament was dissolved and elections fixed for April 2, 2004. Mano-Malik disappeared into thin air (if that were possible as far as Mano was concerned) and once again the battle lines were being drawn for the now-almost annual parliamentary elections.

Ranil took the field with his old team – all his allies from the UNF, the CWC and Rauf Hakeems S1MC, especially by his side. President Chandrika’s PA now had the powerful support of the JVP in a new political formation: the UPFA the United Peoples Freedom Alliance – retaining traces of the People in JVP and the Freedom in SLFP -. It proved to be a winning combination roaring in with massive majorities in several electoral districts.

Ranil stuck to his track record of credible achievement in the two and a quarter years he had run the government. He had promised an end to the war and peace so that people could lead a normal life. He had fulfilled that promise. He had promised the restoration of a run-down economy and the laying of a foundation for sustainable growth. He felt he had achieved this with modest growth ‘the fundamental macro-economic indicators of inflation, budgetary deficits, etc, in order, and renewed investor interest in the economy. He had promised no ‘goodies’ and he had none to hand out yet. That would come later, after the sweat and tears but no blood.

The UPFA campaign too addressed the two chief issues; the peace process and the economy. But directly in contravention of the UNF’s perception of how things had gone in two years the UPFA insisted that the peace process was flawed; it had only been a craven knuckling-down by the government to the unreasonable demands of the LTTE, endangering national security. The UPFA would keep the peace and negotiate with the LTTE but without sacrificing national security and dignity. On the economy, the UPFA maintained that the rich had got richer but the poor had got poorer. The government’s policy prescriptions, dictated by the World Bank and IMF, only favoured the rich – the cost of living had risen and unemployment was rampant.

The electorates choice was decisive as the results of the April 2 election showed:

UPFA

105 seats 45.60%

UNF

82 seats 37.83%

ITAK

22 seats 6.84%

JHU

9 seats 5.97%

SLMC

5 seats 2.02%

No party or coalition had secured the necessary 113 seats for an absolute majority in the 225 member Parliament. No more sustainable alliances appeared possible. Two new political formations with profound significance for the future too had arrived on the scene.

ITAK – the old (1956) Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi – alias Federal Party had emerged after a clean sweep of the north and east and were now virtually the political representatives of the LTTE.

Jatika Hela Urumaya (JHU), the national Sinhala heritage party with only Buddhist monks as its parliamentary representatives had sprung up virtually from nowhere as a protest constituency. It appeared to be a heady mix of middle class professionals, Buddhist devotees. and intellectuals dissatisfied with both mainline parties – the PA and the UNP – and their inability to protect the Sinhala Buddhist identity against the “insidious forces ofTamil separatism, unethical conversions to Christianity, and the sweeping tide of western neo-colonialism under the garb of globalisation.”‘

The polarization of political, economic and social forces had never been seen in such clarity before. The divisive impulses of class – rich against the poor; race Tamil against the Sinhalese (or the Tiger against the Lion); and religion – Buddhists against the Christians – had come back cloaked and garbed, 50 years on to challenge our leaders for the next 50 years. As Ranil, perhaps a trifle wearily, settled down to take stock and address the future, I decided it was time to make my final bow.

(Excerpted from ‘Rendering Unto Caesar’

by Bradman Weerakoon) ✍️

Features

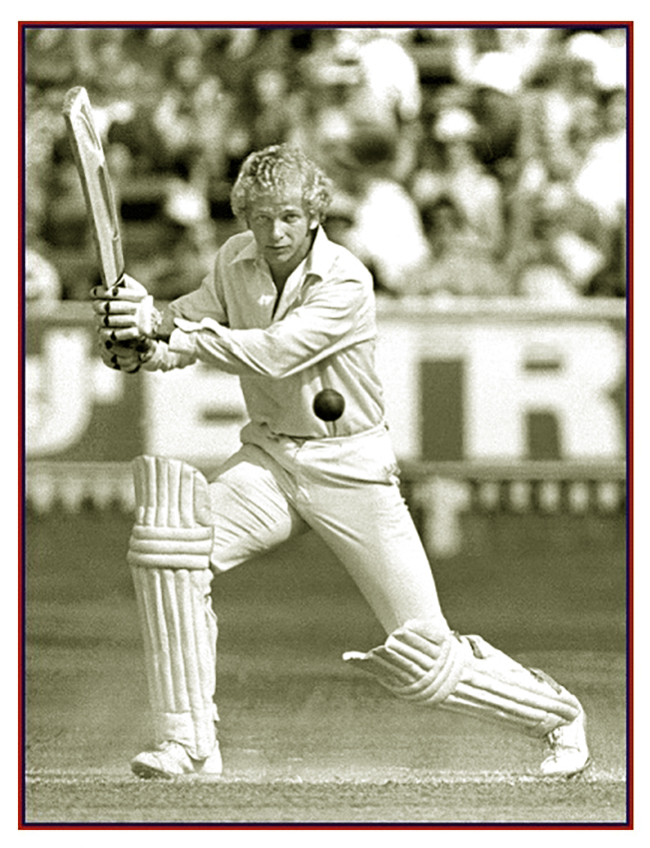

When Batting Was Poetry: Remembering David Gower

For many Sri Lankans growing up in the late nineteen fifties and early sixties, our cricketing heroes were Englishmen. I am not entirely sure why that was. Perhaps it was a colonial hangover, or perhaps it reflected the way cricket was taught locally, with an emphasis on technical correctness, a high left elbow, and the bat close to the pad. English cricket, with its traditions and orthodoxy, became the benchmark.

I, on the other hand, could not see beyond Sir Garfield Sobers and the West Indian team. Sir Garfield remains my all-time hero, although only by a whisker ahead of Muttiah Muralitharan. For me, Caribbean flair and attacking cricket were infinitely superior to the Englishmen’s conservatism and defensive approach.

That said, England has produced many outstanding cricketers, with David Gower and Ian Botham being my favourites. Players such as Colin Cowdrey, Tom Graveney, Mike Denness, Tony Lewis, Mike Brealey, Alan Knott, Derek Underwood, Tony Greig, and David Gower were great ambassadors for England, particularly when touring the South Asian subcontinent, which posed certain challenges for touring sides until about three decades ago. Their calm and dignified conduct when touring is a contrast to the behaviour of the current lot.

I am no longer an avid cricket viewer, largely because my blood pressure tends to rise when I watch our Sri Lankan players. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised recently when I was flipping through the TV channels to hear David Gower’s familiar voice commentating. It brought back fond memories of watching him bat during my time in the UK. I used to look forward to the summer for two reasons. To feel the sun on my back and watch David Gower bat!

A debut that announced a star

One of my most vivid cricketing memories is watching, in 1978, a young English batsman pull the very first ball he faced in Test cricket to the boundary. Most debutants play cautiously, trying to avoid the dreaded zero, but Gower nonchalantly swivelled and pulled a short ball from Pakistan’s Liaquat Ali for four. It was immediately apparent that a special talent had arrived.

To place that moment in perspective, Marvan Atapattu—an excellent Sri Lankan batsman—took three Tests and four innings to score his first run, yet later compiled 16 Test centuries.

Gower went on to score 56 in his first innings and captivated spectators with his full repertoire of strokes, particularly his exquisite cover drive. It is often said that a left-hander’s cover drive is one of the most pleasurable sights in cricket, and watching Sobers, Gower, or Brian Lara execute the cover drive made the entrance ticket worthwhile.

A young talent in a time of change

Gower made his Test debut at just 21, rare for an English player of that era. World cricket was in turmoil due to the Kerry Packer revolution, and England had lost senior players such as Tony Greig, Alan Knott, and Derek Underwood. Selectors were searching for young talent, and Gower’s inclusion injected fresh impetus.

Gower scored his first Test century in only his fourth match, just a month after his debut, against New Zealand, and a few months later scored his maiden Ashes century at Perth.

He finished with 18 Test centuries from 117 matches. His finest test innings, in my view, was the magnificent 154 not out at Kingston in 1981 against Holding, Marshall, Croft, and Garner. Batting for nearly eight hours and facing 403 balls, he set aside flair for determination to save the Test.

He and Ian Botham also benefited from playing their initial years under Mike Brealey, an average batsman but an outstanding leader. Rodney Hogg, the Australian fast bowler, famously said Brealey had a ‘degree in people’, and both young stars flourished under his guidance.

Captaincy and criticism and overall record

Few English batsmen delighted and frustrated spectators and analysts as much as Gower. The languid cover drive, so elegant and so pleasurable to the spectators, also resulted in a fair number of dismissals that, at times, gave the impression of carelessness to both spectators and journalists.

Despite his approach, which at times appeared casual, he was appointed as captain of the English team in 1983 and served for three years before being removed in 1986. He was again appointed captain in 1989 for the Ashes series. He led England in 1985 to a famous Ashes series win as well as a series win in India in1984-85.

In the eyes of some, the captaincy might not have been the best suited to his style of play. However, he scored 732 runs whilst captaining the team during the 1985 Ashes series, proving that he was able handle the pressure.

Under Gower, England lost two consecutive series to the great West Indian teams 5-0, which led to the coining of the phrase “Blackwashed”! He was somewhat unlucky that he captained the English team when the West Indies were at the peak, possessing a fearsome array of fast bowlers.

David Gower scored 3,269 test runs against Australia in 42 test matches. He scored nine centuries and 12 fifties, averaging nearly 45 runs per inning. His record against Australia as an English batsman is only second to Sir Jack Hobbs. Scoring runs against Australia has been a yardstick in determining how good a batsman is. Therefore, his record against Australia can easily rebut the critics who said that he was too casual. He scored 8,231 runs in 117 test matches and 3,170 runs in 114 One Day Internationals.

A gentleman of the game free of controversies

Unlike the other great English cricketer at the time, Ian Botham, David was not involved in any controversies during his illustrious career. The only incident that generated negative press was a low-level flight he undertook in a vintage Tiger Moth biplane in Queensland during the 1990-91 Ashes tour of Australia. The team management and the English press, as usual, made a mountain out of a molehill. David retired from international cricket in 1992.

In 1984, during the tour of India, due to the uncertain security situation after the assassination of the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the English team travelled to Sri Lanka for a couple of matches. I was fortunate enough to get David to sign his book “With Time to Spare”. This was soon after he returned to the pavilion after being dismissed. There was no refusal or rudeness when I requested his signature.

He was polite and obliged despite still being in pads. Although I did not know David Gower, his willingness that day to oblige a spectator exemplified the man’s true character. A gentleman who played the game as it should be, and a great ambassador of England and world cricket. He was inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame in 2009 and appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1992 for his services to sport.

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

Features

Sri Lanka Through Loving Eyes:A Call to Fix What Truly Matters

Love of country, pride, and the responsibility to be honest

I am a Sri Lankan who has lived in Australia for the past 38 years. Australia has been very good to my family and me, yet Sri Lanka has never stopped being home. That connection endures, which is why we return every second year—sometimes even annually—not out of nostalgia, but out of love and pride in our country.

My recent visit reaffirmed much of what makes Sri Lanka exceptional: its people, culture, landscapes, and hospitality remain truly world-class. Yet loving one’s country also demands honesty, particularly when shortcomings risk undermining our future as a serious global tourism destination.

When Sacred and Iconic Sites Fall Short

One of the most confronting experiences occurred during our visit to Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak). This sacred site, revered across multiple faiths, attracts pilgrims and tourists from around the world. Sadly, the severe lack of basic amenities—especially clean, accessible toilets—was deeply disappointing. At moments of real need, facilities were either unavailable or unhygienic.

This is not a luxury issue. It is a matter of dignity.

For a site of such immense religious and cultural significance, the absence of adequate sanitation is unacceptable. If Sri Lanka is to meet its ambitious tourism targets, essential infrastructure, such as public toilets, must be prioritized immediately at Sri Pada and at all major tourist and pilgrimage sites.

Infrastructure strain is also evident in Ella, particularly around the iconic Nine Arches Bridge. While the attraction itself is breathtaking, access to the site is poorly suited to the sheer volume of visitors. We were required to walk up a steep, uneven slope to reach the railway lines—manageable for some, but certainly not ideal or safe for elderly visitors, families, or those with mobility challenges. With tourist numbers continuing to surge, access paths, safety measures, and crowd management urgently needs to be upgraded.

Missed opportunities and first impressions

Our visit to Yala National Park, particularly Block 5, was another missed opportunity. While the natural environment remains extraordinary, the overall experience did not meet expectations. Notably, our guide—experienced and deeply knowledgeable—offered several practical suggestions for improving visitor experience and conservation outcomes. Unfortunately, he also noted that such feedback often “falls on deaf ears.” Ignoring insights from those on the ground is a loss Sri Lanka can ill afford.

First impressions also matter, and this is where Bandaranaike International Airport still falls short. While recent renovations have improved the physical space, customs and immigration processes lack coherence during peak hours. Poorly formed queues, inconsistent enforcement, and inefficient passenger flow create unnecessary delays and frustration—often the very first experience visitors have of Sri Lanka.

Excellence exists—and the fundamentals must follow

That said, there is much to celebrate.

Our stays at several hotels, especially The Kingsbury, were outstanding. The service, hospitality, and quality of food were exceptional—on par with the best anywhere in the world. These experiences demonstrate that Sri Lanka already possesses the talent and capability to deliver excellence when systems and leadership align.

This contrast is precisely why the existing gaps are so frustrating: they are solvable.

Sri Lankans living overseas will always defend our country against unfair criticism and negative global narratives. But defending Sri Lanka does not mean remaining silent when basic standards are not met. True patriotism lies in constructive honesty.

If Sri Lanka is serious about welcoming the world, it must urgently address fundamentals: sanitation at sacred sites, safe access to major attractions, well-managed national parks, and efficient airport processes. These are not optional extras—they are the foundation of sustainable tourism.

This is not written in criticism, but in love. Sri Lanka deserves better, and so do the millions of visitors who come each year, eager to experience the beauty, spirituality, and warmth that our country offers so effortlessly.

The writer can be reached at Jerome.adparagraphams@gmail.com

By Jerome Adams

Features

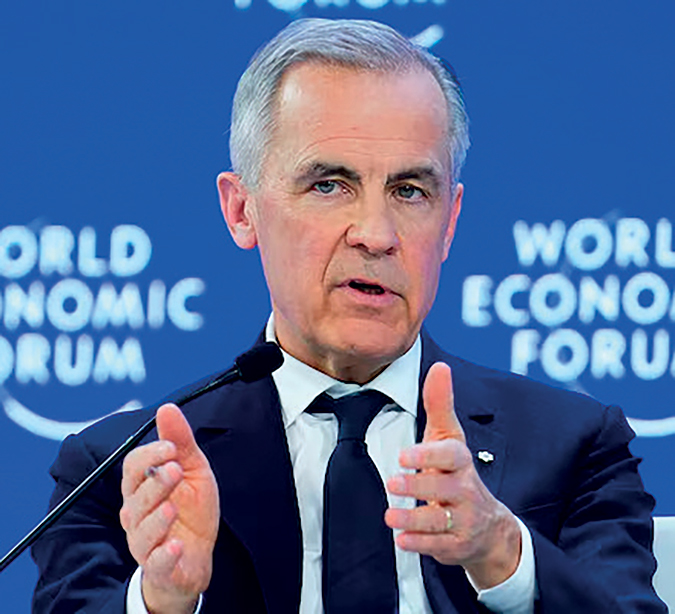

Seething Global Discontents and Sri Lanka’s Tea Cup Storms

Global temperatures in January have been polar opposite – plus 50 Celsius down under in Australia, and minus 45 Celsius up here in North America (I live in Canada). Between extremes of many kinds, not just thermal, the world order stands ruptured. That was the succinct message in what was perhaps the most widely circulated and listened to speeches of this century, delivered by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at Davos, in January. But all is not lost. Who seems to be getting lost in the mayhem of his own making is Donald Trump himself, the President of the United States and the world’s disruptor in chief.

After a year of issuing executive orders of all kinds, President Trump is being forced to retreat in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by the public reaction to the knee-jerk shooting and killing of two protesters in three weeks by federal immigration control and border patrol agents. The latter have been sent by the Administration to implement Trump’s orders for the arbitrary apprehension of anyone looking like an immigrant to be followed by equally arbitrary deportation.

The Proper Way

Many Americans are not opposed to deporting illegal and criminal immigrants, but all Americans like their government to do things the proper way. It is not the proper way in the US to send federal border and immigration agents to swarm urban neighbourhood streets and arrest neighbours among neighbours, children among other school children, and the employed among other employees – merely because they look different, they speak with an accent, or they are not carrying their papers on their person.

Americans generally swear by the Second Amendment and its questionably interpretive right allowing them to carry guns. But they have no tolerance when they see government forces turn their guns on fellow citizens. Trump and his administration cronies went too far and now the chickens are coming home to roost. Barely a month has passed in 2026, but Trump’s second term has already run into multiple storms.

There’s more to come between now and midterm elections in November. In the highly entrenched American system of checks and balances it is virtually impossible to throw a government out of office – lock, stock and barrel. Trump will complete his term, but more likely as a lame duck than an ordering executive. At the same time, the wounds that he has created will linger long even after he is gone.

Equally on the external front, it may not be possible to immediately reverse the disruptions caused by Trump after his term is over, but other countries and leaders are beginning to get tired of him and are looking for alternatives bypassing Trump, and by the same token bypassing the US. His attempt to do a Venezuela over Greenland has been spectacularly pushed back by a belatedly awakening Europe and America’s other western allies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The wags have been quick to remind us that he is mostly a TACO (Trump always chickens out) Trump.

Grandiose Scheme or Failure

His grandiose scheme to establish a global Board of Peace with himself as lifetime Chair is all but becoming a starter. No country or leader of significant consequence has accepted the invitation. The motley collection of acceptors includes five East European countries, three Central Asian countries, eight Middle Eastern countries, two from South America, and four from Asia – Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Pakistan. The latter’s rush to join the club will foreclose any chance of India joining the Board. Countries are allowed a term of three years, but if you cough up $1 billion, could be member for life. Trump has declared himself to be lifetime chair of the Board, but he is not likely to contribute a dime. He might claim expenses, though. The Board of Peace was meant to be set up for the restoration of Gaza, but Trump has turned it into a retirement project for himself.

There is also the ridiculous absurdity of Trump continuing as chair even after his term ends and there is a different president in Washington. How will that arrangement work? If the next president turns out to be a Democrat, Trump may deny the US a seat on the board, cash or no cash. That may prove to be good for the UN and its long overdue restructuring. Although Trump’s Board has raised alarms about the threat it poses to the UN, the UN may end up being the inadvertent beneficiary of Trump’s mercurial madness.

The world is also beginning to push back on Trump’s tariffs. Rather, Trump’s tariffs are spurring other countries to forge new trade alliances and strike new trade deals. On Tuesday, India and EU struck the ‘mother of all’ trade deals between them, leaving America the poorer for it. Almost the next day , British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced in Beijing that they had struck a string of deals on travel, trade and investments. “Not a Big Bang Free Trade Deal” yet, but that seems to be the goal. The Canadian Prime Minister has been globe-trotting to strike trade deals and create investment opportunities. He struck a good reciprocal deal with China, is looking to India, and has turned to South Korea and a consortium from Germany and Norway to submit bids for a massive submarine supply contract supplemented by investments in manufacturing and mineral industries. The informal first-right-of-refusal privilege that US had in Canada for defense contracts is now gone, thanks to Trump.

The disruptions that Trump has created in the world order may not be permanent or wholly irreversible, as Prime Minister Carney warned at Davos. But even the short term effects of Trump’s disruptions will be significant to all of US trading partners, especially smaller countries like Sri Lanka. Regardless of what they think of Trump, leaders of governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens from the negative effects of Trump’s tariffs. That will be in addition to everything else that governments have to do even if they do not have Trump’s disruptions to deal with.

Bland or Boisterous

Against the backdrop of Trump-induced global convulsions, politics in Sri Lanka is in a very stable mode. This is not to diminish the difficulties and challenges that the vast majority of Sri Lankans are facing – in meeting their daily needs, educating their children, finding employment for the youth, accessing timely health care and securing affordable care for the elderly. The challenges are especially severe for those devastated by cyclone Ditwah.

Politically, however, the government is not being tested by the opposition. And the once boisterous JVP/NPP has suddenly become ‘bland’ in government. “Bland works,” is a Canadian political quote coined by Bill Davis a nationally prominent premier of the Province of Ontario. Davis was responding to reporters looking for dramatic politics instead of boring blandness. He was Premier of Ontario for 14 years (1971-1985) and won four consecutive elections before retiring.

No one knows for how long the NPP government will be in power in Sri Lanka or how many more elections it is going to win, but there is no question that the government is singularly focused on winning the next parliamentary election, or both the presidential and parliamentary elections – depending on what happens to the system of directly electing the executive president.

The government is trying to grow comfortable in being on cruise control to see through the next parliamentary election. Its critics on the other hand, are picking on anything that happens on any day to blame or lampoon the government. The government for all its tight control of its members and messaging is not being able to put out quickly the fires that have been erupting. There are the now recurrent matters of the two AGs (non-appointment of the Auditor General and alleged attacks on the Attorney General) and the two ERs (Educational Reform and Electricity Reform), the timing of the PC elections, and the status of constitutional changes to end the system of directly electing the president.

There are also criticisms of high profile resignations due to government interference and questionable interdictions. Two recent resignations have drawn public attention and criticism, viz., the resignation of former Air Chief Marshal Harsha Abeywickrama from his position as the Chairman of Airport & Aviation Services, and the earlier resignation of Attorney-at-Law Ramani Jayasundara from her position as Chair of the National Women’s Commission. Both have been attributed to political interferences. In addition, the interdiction of the Deputy Secretary General of Parliament has also raised eyebrows and criticisms. The interdiction in parliament could not have come at a worse time for the government – just before the passing away of Nihal Seniviratne, who had served Sri Lanka’s parliament for 33 years and the last 13 of them as its distinguished Secretary General.

In a more political sense, echoes of the old JVP boisterousness periodically emanate in the statements of the JVP veteran and current Cabinet Minister K.D. Lal Kantha. Newspaper columnists love to pounce on his provocative pronouncements and make all manner of prognostications. Mr. Lal Kantha’s latest reported musing was that: “It is true our government is in power, but we still don’t have state power. We will bring about a revolution soon and seize state power as well.”

This was after he had reportedly taken exception to filmmaker Asoka Handagama’s one liner: “governing isn’t as easy as it looks when you are in the opposition,” and allegedly threatened to answer such jibes no matter who stood in the way and what they were wearing “black robes, national suits or the saffron.” Ironically, it was the ‘saffron part’ that allegedly led to the resignation of Harsha Abeywickrama from the Airport & Aviation Services. And President AKD himself has come under fire for his Thaipongal Day statement in Jaffna about Sinhala Buddhist pilgrims travelling all the way from the south to observe sil at the Tiisa Vihare in Thayiddy, Jaffna.

The Vihare has been the subject of controversy as it was allegedly built under military auspices on the property of local people who evacuated during the war. Being a master of the spoken word, the President could have pleaded with the pilgrims to show some sensitivity and empathy to the displaced Tamil people rather than blaming them (pilgrims) of ‘hatred.’ The real villains are those who sequestered property and constructed the building, and the government should direct its ire on them and not the pilgrims.

In the scheme of global things, Sri Lanka’s political skirmishes are still teacup storms. Yet it is never nice to spill your tea in public. Public embarrassments can be politically hurtful. As for Minister Lal Kantha’s distinction between governmental mandate and state power – this is a false dichotomy in a fundamentally practical sense. He may or may not be aware of it, but this distinction quite pre-occupied the ideologues of the 1970-75 United Front government. Their answer of appointing Permanent Secretaries from outside the civil service was hardly an answer, and in some instances the cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

As well, what used to be a leftist pre-occupation is now a right wing insistence especially in America with Trump’s identification of the so called ‘deep state’ as the enemy of the people. I don’t think the NPP government wants to go there. Rather, it should show creative originality in making the state, whether deep or shallow, to be of service to the people. There is a general recognition that the government has been doing just that in providing redress to the people impacted by the cyclone. A sign of that recognition is the number of people contributing to the disaster relief fund and in substantial amounts. The government should not betray this trust but build on it for the benefit of all. And better do it blandly than boisterously.

by Rajan Philips

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoGovt. provoking TUs