Features

Ananda Coomaraswamy on Arts and Crafts:

A Review of Ayesha Wickramasinghe’s ‘The Dress of Women in Sri Lanka’ – part II

by Laleen Jayamanne

(Continued from yesterday)

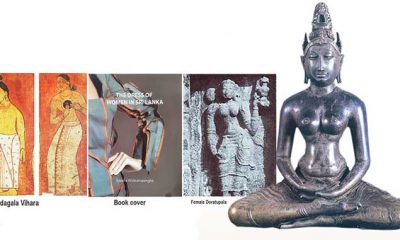

Dr. Ayesha Wickramasinghe, with her technical skills and historical interests, appears to have heard Coomaraswamy’s implicit call to study the neglected crafts of Lanka, to look back at our traditions of dress, even as she is focused on the technological future of the craft with her students. As a contemporary designer, she is interested in developing new industrial techniques and materials suited to the 21st Century, with sustainability as a value. She has researched clothing and ornament to understand their forms and functions within a rapidly changing modern era, unlike the relatively stable era of pre-1815 Kandyan Kingdom, where the traditional crafts were practised as they were perennially, nourished by South Indian and indigenous craft practices and craftsmen. Despite its modest disclaimer, Coomaraswamy’s scholarship is peerless. Wickramasinghe on her part, dedicates her book to, ‘The unknown designers who have created clothing fashions of ancient Sri Lanka.’ She draws from a wide variety of sources including Coomaraswamy’s text and the handful of books on clothing and costume in Lanka and also from Lanka’s long history of art which includes temple paintings and stone sculpture. What she does with these sources is ingenious.

The book is broadly divided into six sections and a conclusion. The presentation begins with the variety in female ornamentation and textiles and then progresses chronologically. She shows examples of female dress sculpted on stone figures, from the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods and in temple paintings within the colonial era. A stone sculptural figure (Anuradhapura Museum), the life-size bronze of the Bodhisattva icon Tara (8th Century, British Museum), and a female Doratupala (13th Century) Dalada Maligava, Yapahuva, are all seen clad in very finely woven garments covering the lower part of the bodies, while the breasts are left uncovered. The more familiar Sigiriya frescoes are also presented. Perhaps with the Indian Hindu influence, the display of semi-clothed bodies is accepted and appreciated without the sense of shame endemic to the Christian European traditions of the colonisers, in relation to human flesh, and the body, burdened by the idea of ‘Original Sin’. Puritanical, Victorian patriarchal values are said to have been introduced to Lanka by the Christian English colonisers and consolidated by Lankan middle classes themselves, such as the influential nationalist and social reformer, Anagarika Dharmapala, who incorporated these values, according to the anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekera. He coined the astute phrase, ‘Protestant- Buddhism,’ to capture this phenomenon. More of this later.

Wickramasinghe takes account of the island’s geography, situated on trade routes, as a factor in its hybridised forms of dress. The topic of colonialism explores the Western influence on local upper-class women’s taste. The broad political theme of decolonisation of dress, emphasising ethnic differences, nationalism and dress among the Sinhala folk and dress among other groups, including the low caste, and very poor women of the Sakkiliya caste or Dalit women, are also presented. The final chapter deals with the period after 1977 when the economy was opened up to neo-liberal globalisation, which created a ‘free-trade zone’ to manufacture garments, to encourage foreign capital by providing cheap female labour.

Genesis of Art in Human Craft Labour

In the feudal 18th Century that Coomaraswamy studied, there was of course a hierarchical social structure, but even the most humble craftsman belonged to an integrated community. It is worth noting that he thought it worth publishing in the book a large number of songs kavi that crafts persons sang while working. In English, the word ‘yarn’ means both thread and also to tell a tale, as in ‘to spin a yarn’. These two examples indicate the vital fact of the link between the deep history of human craft skills and the creation and emergence of art itself (story-telling and song, for example), from these very craft practices, that is from human labour. This is the deep link between arts and crafts, like twins, linking the hand and the mouth, dance and song emerging from spinning and weaving. This is the very heart of his philosophical intuition of the integral links between craft, human labour and art. It is this civilisational loss which Coomaraswamy wrote about and documented and preserved for posterity, at the Boston Fine Art Museum in the US, where he was the curator of Indian, Persian and Islamic Art. He lived and worked in the US from 1917 until his death in 1947. He was forced to leave England because he spoke up against joining WWI and also against British colonial rule in India and Ceylon. His property was confiscated but America gave him refuge, where he published some of his major works.

Lankan Elephants and Ivory Crafts

I saw at the Boston Fine Art Museum an exquisitely carved little ivory box and was delighted to read that it was from Ceylon! Though indeed in his book Coomaraswamy says that the collection of ivory carvings is rather large in Lanka, whereas there is relatively very little ivory work in India. Then he goes on to say that the Hindus would have found working on a material from an animal source unacceptable, polluting. One wonders how a Buddhist country reconciled this, especially because Coomaraswamy says that tusked elephants were very rare in Lanka. Were the tusks taken from dead elephants, who by the way have long natural lives, and what of the huge tusks that are ceremonially such an integral part of contemporary Lankan Sinhala Nationalist State ceremonies and religious ritual? Learning this deep history, I find the tusk decoration rather grotesque, inhumane. We know that the English loved to go on shooting sprees killing Lankan wild animals, but then they left in 1947 and the profound Buddhist doctrine of Ahimsa (non-violence) toward all sentient life is not a Christian virtue.

Fashion Industry: Cheap Female Labour

Wickramasinghe goes on to say that the fashion industry in Lanka is now very large and provides employment for many women. Whether the young women get burnt out by very poor work conditions in the free trade zone, appears not to concern successive governments. According to the young trade union leader, labour lawyer and prominent political activist, Swasthika Arulingam, the garment workers have very few labour rights even now after over four decades.

However, a plethora of global styles and materials were made affordable as a result of the garment industry, democratising sartorial tastes and providing access to fashion to a large number of people across social classes. One can view the rather wide use of denim jeans by young women, as an example of equalising gendered dress through a unisex-garment. It would appear that traditional ideas of femininity are also being questioned by women through access to new forms of clothing, education in feminist ideas and politics and access to the internet which diminishes Lankan insularity.

Pop-Cultural Influence

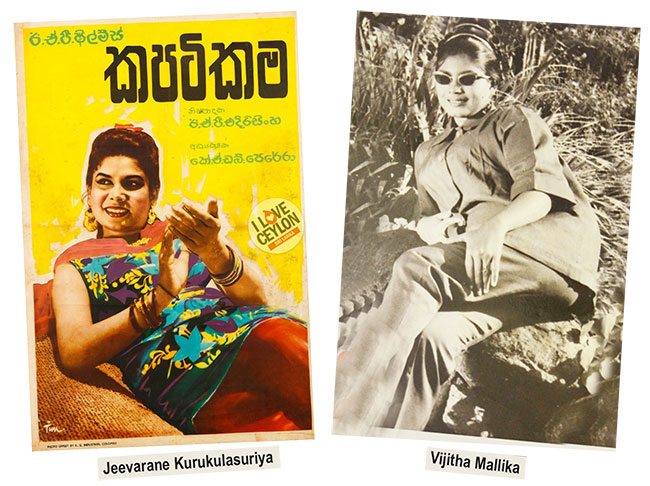

Two unusual examples of dress innovation for comfort and style are presented in stills from two popular Sinhala films from the 1960s, which have now returned in newer styles. A popular star at the time, Jeevarani Kurukulasooriya, is seen lounging in a salwar kameez, while in Hithata Hitha (1965), Vijitha Mallika lounges stylishly in slacks and a top with a shirt collar, all in a single dark colour. The ‘60s are presented as an era when mini-skirts and bell-bottom pants and jeans became popular among the middle classes who enjoyed the freedom of movement and sense of fun these garments provided in feeling connected to the youth pop culture of the West seen in Hollywood films and fashion magazines. This was indeed part of my world along with that of my school friends during that period in Colombo. We also loved a frock called a Tent, which looked like one, where the body floated in the garment.

The Sari-Drama in Parliament

So, with this diverse, long Lankan sartorial history, it’s surprising to see the current controversy about the female dress mandated for Lankan school teachers, who are expected to wear either a sari or the upcountry Ohoriya to school. The ‘problem’ arose when a group of teachers decided recently to collectively flout this mandate by wearing comfortable clothes they thought were appropriate for their professional work. Among the photos they posted, there was a teacher wearing a smart salwar kameez, a set of clothes worn by Muslim women with the Dupatta shawl, and also a Kurta, again an elegant, uni-sex garment traditionally worn by men across North India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, going further back to the ancient Persian Imperial era. It is a tailored garment, unlike the draped clothing of ancient India and Greece. During the Persian wars, they introduced the tailored garment to Classical Greece where both men and women wore draped clothing.

In the 19th Century, the highly influential Sinhala Buddhist social reformer, Anagarika Dharmapala expressed the following, says Wickramasinghe.

“Dharmapala stated that the Ohoriya and sari were the most suitable attire for Sri Lankan women. The morally acceptable dress covered the entire body with a proper blouse and a cloth ten riyans long.” (N. Wickramasinghe, Dressing the Colonised Body; Politics, Clothing and identity. New Delhi; Longman, 2003) p195.

This is an encapsulation of a ‘Protestant-Buddhist’ sentiment identified by Obeyesekera, referred to earlier. It appears then that in linking morality with forms of dress, some Sinhala male attitudes to women’s clothing are still stuck in the puritanical and patriarchal mores of the 19th Century English Victorian era. Besides the Dalit women who did the municipal labour of sweeping streets and cleaning public toilets and the Malaiyahi women who plucked tea would not have been able to afford the stipulated 10 riyan. But then he was not addressing them!

Women in a Teachers’ Trade Union have calmly and rationally explained to the public that they wanted the freedom to wear garments of their choice to the schools in which they teach, clothes that combine comfort and professional decorum. They have said clearly that to mandate the sari for teachers is an unreasonable rule. Its cost, its considerable upkeep and lack of ease of movement in scrambling onto packed buses have made some of them choose to wear garments they deem suitable for their workplace which combine comfort and ease. It would appear that some men fear that their ability to control women is at risk. Dress is a powerful means of expression of a sense of freedom and comfort of self-enjoyment in ease of movement. This is amply demonstrated in the history of the Western Women’s Movements of the 20th Century. The teachers who question the sari mandate do not dislike the sari or Ohoriya – how could one, when the two garments are mostly so beautiful, for the right occasion and time? But Lankan women will decide when they would like to wear it and how exactly to drape it and the way in which they will style their hair and blouses.

Women’s Dress and Resistance to Patriarchy

Coincidentally, Ayesha Wickramasinghe’s book provides a timely synoptic vision of the diversity of Lankan women’s dress across the ages, at this very moment of an important feminist act of political resistance, within the wider ongoing political struggle in Lanka. Lankan teachers and other professionals with a social conscience have repeatedly highlighted how the current economic crisis is affecting poor young school students’ ability to learn, or even attend school because of the cost of travel, lack of proper clothes and shoes and even food. As many say, these are the matters that need to be addressed urgently in parliament. If ignorant men invoke the ‘sanctity of Sinhala- Buddhist tradition’ against western influence, sitting in a Westminster style Democratic parliament, one could rhetorically ask, which Buddhist traditions, because there are several and the many Taras are clad in marvellous clothes and ornaments in Tibet and Nepal, in the Mahayana traditions of meditation.

Guru-Shishya-Parampara in Lanka

Because I have chosen to frame my account of Ayesha’s book on The Dress of Women in Sri Lanka with Ananda Coomaraswamy’s book on Mediaeval Sinhalese Arts and Crafts, I would like to conclude with a few personal thoughts about this most gifted of scholars. Of mixed parentage, with an English mother, on his father’s side he comes from one of the most illustrious Jaffna Tamil families of Lanka. His father, Sir Muttu Coomaraswamy (who died when Ananda was just three), had two brilliant nephews, Arunachalam Ponnambalam and Arunachalam Ramanadan, who played major public roles in colonial Ceylon. Two halls of residence at Peradeniya University are named after them. Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy’s very name (a serendipitous combination of Sinhala, English and Tamil), appears now, more than ever, as a beacon of light to contemporary Lankan scholarship. His profound work admonishes us not to delimit Lankan humanities research within a narrow Sinhala-Buddhist- Nationalist, supremacist-ideology of art and politics, but rather, to widen our perspectives by understanding the rich diversity of cultures, languages and religions of Lanka which includes its many traditions of dress. Ananda had hoped to spend his last years in his beloved India as a Sanyasi, but he died suddenly of a heart attack, in his Japanese garden in New England, beside his Brazilian wife. His ashes, it is said, were released into the Ganga but some of it set afloat in a river in Lanka.

Features

Sri Lanka deploys 4,700 security personnel to protect electric fences amid human-elephant conflict

By Saman Indrajith

Sri Lanka has deployed over 4,700 Civil Security Force personnel to protect the electric fences installed to mitigate human-elephant conflict, Minister of Environment Dammika Patabendi told Parliament on Thursday.

The minister stated that from 2015 to 2024, successive governments have spent 906 million rupees (approximately 3.1 million U.S. dollars) on constructing elephant fences. During this period, 5,612 kilometers of electric fencing have been built.

He reported that between 2015 and 2024, 3,477 wild elephants and 1,190 people lost their lives due to human-elephant conflict. Electric fences remain a key measure in controlling this crisis, he added.

Between January 1 and 31, 2025, 43 elephants and three people have died as a result of such conflicts. Additionally, 21,468 properties have been damaged between 2015 and 2024, the minister noted.

Features

Electoral reform and abolishing the executive presidency

by Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

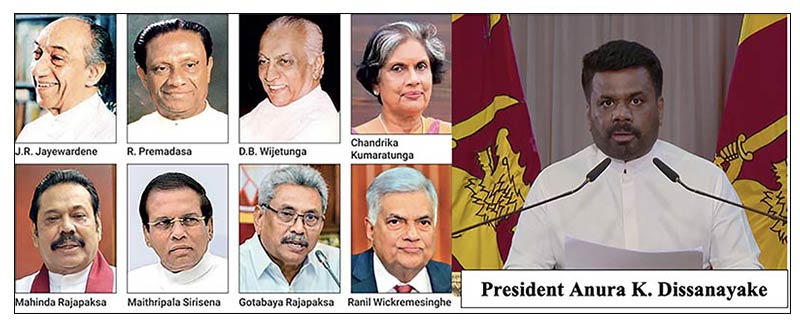

The Sri Lankan Left spearheaded the campaign against introducing the executive presidency and consistently agitated for its abolition. Abolition was a central plank of the platform of the National People’s Power (NPP) at the 2024 presidential elections and of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) at all previous elections.

Issues under FPP or a mixed system

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, participating in the ‘Satana’ programme on Sirasa TV, recently reiterated the NPP’s commitment to abolition and raised four issues related to accompanying electoral reform.

The first is that proportional representation (PR) did not, except in a few instances, give the ruling party a clear majority, resulting in a ‘weak parliament’. Therefore, electoral reform is essential when changing to a parliamentary form of government.

Secondly, ensuring that different shades of opinion and communities are proportionally represented may be challenging under the first-past-the-post system (FPP). For example, as the Muslim community in the Kurunegala district is dispersed, a Muslim-majority electorate will be impossible. Under PR, such representation is possible, as happened in 2024, with many Muslims voting for the NPP and its Muslim candidate.

The third issue is a difficulty that might arise under a mixed (FPP-PR) system. For example, the Trincomalee district returned Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim candidates at successive elections. In a mixed system, territorial constituencies would be fewer and ensuring representation would be difficult. For the unversed, there were 160 electorates that returned 168 members under FPP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

The fourth is that certain castes may not be represented under a new system. He cited the Galle district where some of the ‘old’ electorates had been created to facilitate such representation.

It might straightaway be said that all four issues raised by President Dissanayake have substantial validity. However, as the writer will endeavour to show, they do not present unsurmountable obstacles.

Proposals for reform, Constitutional Assembly 2016-18

Proposals made by the Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly of the 2015 Parliament and views of parties may be referred to.

The Committee proposed a 233-member First Chamber of Parliament elected under a Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system that seeks to ensure proportionality in the final allocation of seats. 140 seats (60%) will be filled by FPP. The Delimitation Commission may create dual-member constituencies and smaller constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest, whether racial, religious or otherwise. 93 compensatory seats (40%) will be filled to ensure proportionality. Of these, 76 will be filled by PR at the provincial level and 12 by PR at the national level, while the remaining 5 seats will go to the party that secures the highest number of votes nationally.

The Sri Lanka Freedom Party agreed with the proposals in principle, while the Joint Opposition (the precursor of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna) did not make any specific proposals. The Tamil Nationalist Alliance was willing to consider any agreement between the two main parties on the main principles in the interest of reaching an acceptable consensus.

The Jathika Hela Urumaya’s position was interesting. If the presidential powers are to be reduced, the party obtaining the highest number of votes should have a majority of seats. Still, the representation of minor political parties should be assured. Therefore, the number of seats added to the winning party should be at the expense of the party placed second.

The All Ceylon Makkal Congress, Eelam People’s Democratic Party, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and the Tamil Progressive Alliance jointly proposed that the principles of the existing PR system be retained but with elections being held for 40 to 50 electoral zones and a 2% cut-off point. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna was for the abolition of the executive presidency and, interestingly, suggested a mixed electoral system that ensures that the final outcome is proportional.

CDRL proposals

The Collective for Democracy and Rule of Law (CDRL), a group of professionals and academics that included the writer, made detailed proposals on constitutional reform in 2024. It proposed returning to parliamentary government. The legislature would be bicameral, with a House of Representatives of 200 members elected as follows: 130 members will be elected from territorial constituencies, including multi-member and smaller constituencies carved out to facilitate the representation of social groups of shared interest; Sixty members will be elected based on PR at a national or provincial level; Ten seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that failed to secure a seat through territorial constituencies or the sixty seats mentioned above, enabling small parties with significant national presence without local concentration to secure representation. Appropriate provisions shall be made to ensure adequate representation of women, youth and underrepresented interest groups.

The writer’s proposal

The people have elected the NPP leader as President and given the party a two-thirds majority in Parliament. It is, therefore, prudent to propose a system that addresses the concerns expressed by the President. Otherwise, we will be going around in circles. The writer believes that the CDRL proposals, suitably modified, present a suitable basis for further discussion.

While the people vehemently oppose any increase in the number of MPs, it would be challenging to address the President’s concerns in a smaller parliament. The writer’s proposal is, therefore, to work within a 225-member Parliament.

The writer proposes that 150 MPs be elected through FPP and 65 through national PR. 10 seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that have not secured a seat either through territorial constituencies or the 65 seats mentioned above. The Delimitation Commission shall apportion 150 members among the various provinces proportionally according to the number of registered voters in each province. The Commission will then divide each province into territorial constituencies that will return the number of MPs apportioned. The Commission may create smaller constituencies or multi-member constituencies to render possible the representation of social groups of shared interest.

The 65 PR seats will be proportionally distributed according to the votes received by parties nationally, without a cut-off point. The number of ‘PR MPs’ that a party gets will be apportioned among the various provinces in proportion to the votes received in the provinces. For example, if Party A is entitled to 10 PR seats and has obtained 20% of its total vote from the Central Province, it will fill 2 PR seats from candidates from that Province, and so on. Each party shall submit names of potential ‘PR MPs’ from each of the provinces where the party contests at least one constituency in the order of its preference, and seats allotted to that party in a given province are filled accordingly. The remaining 10 seats will be filled by small parties as proposed by the CDRL.

How does the proposed system address President Dissanayake’s concerns?

The President’s concern that PR will result in a weak parliament is sufficiently addressed when a majority of MPs are elected under FPP.

Before dealing with the other three issues, it must be said that voters do not always vote for candidates from their communities. A classic example is the 1965 election result in Balapitiya, a Left-oriented constituency dominated by a particular caste. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party boldly nominated L.C. de Silva, from a different caste, to contest Lakshman de Silva, a long-standing MP who crossed over to bring down the SLFP-LSSP coalition. Balapitiya voters punished Lakshman and elected L.C.

Multi-member constituencies have generally served their purpose but not always. The Batticaloa dual-member constituency had been created to ‘render possible’ the election of a Tamil and a Muslim. At the 1970 elections, the four leading candidates were Rajadurai of the Federal Party, Makan Markar of the UNP, Rahuman of the SLFP and the independent Selvanayagam. The Muslim vote was closely split between Macan Markar and Rahuman, resulting in both losing. Muslim voters surely knew that a split might deny Muslim representation but preferred to vote according to their political convictions.

The President’s second concern that a dispersed community may not get representation under FPP will also be addressed better under the proposed system. Taking the same Kurunegala district as an example, a party could attract Muslim voters by placing a Muslim high up on the PR list. Similarly, a Tamil party could place a candidate from a depressed community high up in its Northern Province PR list to attract voters of depressed communities and ensure their representation.

The third concern was that the number of electorates would be less under a mixed system, making it challenging to carve out electorates to facilitate the representation of communities, the Trincomalee district being an example. Empowering the Delimitation Commission to create smaller electorates assuages this concern. It will not be Trincomalee District but the whole Eastern Province to which a certain number of FPP MPs will be allotted, giving the Commission broad discretion to carve out electorates. The Commission could also create multimember constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest. The fourth concern about caste representation would also be addressed similarly.

It may be noted that the difference between the number of FPP MPs (150) under the proposed system is only 10% less than that under the delimitation of 1975 (168). Also, there will be no cut-off point for PR as against the present cut-off of 5%. This will help small as well as not-so-small parties. Reserving 10 seats for small parties also helps address the concerns of the President.

No spoilers, please. Don’t let electoral reform be an excuse for a Nokerena Wedakama

The writer submits the above proposals as a basis for discussion. While a stable government and the representation of various interests are essential, abolishing the dreaded Executive Presidency is equally important. These are not mutually exclusive.

President Dissanayake also said on Sirasa TV that once the local elections are over, the NPP would first discuss the issue internally. This is welcome as there would be a government position, which can be the basis for further discussion.

This is the first time a single political party committed to abolition has won a two-thirds majority. Another such opportunity will almost certainly not come. Let there be no spoilers from either side. Let electoral reform not be an excuse for retaining the Executive Presidency. Let the Sinhala saying ‘nokerena veda kamata konduru thel hath pattayakuth thava tikakuth onalu’ not apply to this exercise (‘for the doctoring that will never come off, seven measures and a little more, of the oil of eye-flies are required’—translation by John M. Senaveratne, Dictionary of Proverbs of the Sinhalese, 1936).

According to recent determinations of the Supreme Court, a change to a parliamentary form of government requires the People’s approval at a referendum. While the NPP has a two-thirds majority, it should not take for granted a victory at a referendum held late in the term of Parliament for, then, there is the danger of a referendum becoming a referendum on the government’s performance rather than one on the constitutional bill, with opposition parties playing spoilers. If the government wishes to have the present form of government for, say, four years, it could now move a bill for abolition with a sunset clause that provides for abolition on a specified date. Delay will undoubtedly frustrate the process and open the government to the accusation that it indulged in a ‘nokerena vedakama’.

Features

Did Rani miss manorani ?

(A film that avoids the ‘Mannerism’ of a Biopic: Rani)

by Bhagya Rajapakshe

bhagya8282@gmail.com

This is only how Manorani sees Richard. It doesn’t have a lot of what Richard did. Although Manorani is not someone who pays attention to the happenings in the country. It was only after her son was kidnapped that she began to feel that this was happening in the country.She had human emotions. But she was a person who smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey and lived a merry life.”

(Interview with “Rani” film director Ashoka Handagama by Upali Amarasinghe – 02.02.2025 ‘Anidda’ weekend newspaper, pages 15 and 19)

The above statement shows the key attitude of the director of the movie, “Rani” towards the central character of the film, Dr. Manorani Sarawanamuttu. This statement is highly controversial. Similarly, the statement given by the director to Groundviews on 30.01.2025 about capturing the depth of Rani’s character shows that he has done so superficially, frivolously?

A biopic is a specific genre of cinema. This genre presents true events in the life of a person (a biography), or a group of people who are currently alive or who belong to history with recognisable names. The biopic genre often artistically and cinematically explores keenly the main character along with a few secondary characters connected to the central figure. World cinema is proof that even if the characters are centuries old, they are carefully researched and skilled directors take care to weave the biographies into their films without causing any harm or injustice to the original character.

According to the available authentic reports, Manorani Saravanamuthu was a professionally responsible medical doctor. Chandri Peiris, a close friend of her family, in his feature article on Manorani in the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper on 06th November 2021, says this about her:

“She was a doctor who had her surgeries in the poorest areas around Colombo which made her popular with communities who preferred their women to be seen by female doctors. She had a wonderful manner with her patients which my mother described by saying, ‘looking at her is enough to make you well …. When it came to our outlandish group of friends, she was always there to steer many of us through some very personal issues such as: unplanned pregnancies, teenage pregnancies, mental breakdowns, STD’s, young lovers who ran away and married, depression, circumcisions, break-ups, fractures, dance injuries, laryngitis (especially among the actors and singers) fevers, pimples, and even the odd boil on the bum.”

But the image of Rani depicted by Handagama in his film is completely different from this. According to the film, a major feature of her life consisted of drinking whiskey and smoking cigarettes. Her true role is unspoken, hidden in the film. A grave question arises as to whether the director spent adequate time doing the research? to find out who Manorani really was. In his article Chandri Peiris further says the following about Manorani:

“Soon after the race riots in 1983, Manorani (along with Richard) helped a great many Sri Lankan Tamils to find refuge in countries all over the world. Nobody knew about this. But all of us who used to hang around their house kept seeing unfamiliar people come over to stay a few days and then leave. Among them were the three sons of the Master-in-Charge of Drama at S. Thomas’ College, who were swiftly sent abroad by the tireless efforts of this mother and son. It was then that we worked out that their home was a safehouse. … Manorani was vehemently opposed to the terror wreaked by the LTTE and always wanted Sri Lanka to be one country that was home to the many diverse cultures within it. When the ethnic strife developed into a full-on war with those who wanted to create a separate state for Tamil Eelam, she remained completely against it.”

According to the director of the film, if Rani had no awareness of what was happening in the country and the world, how could she have helped the victims survive and leave the country during that life-threatening period? It is clear from all this that the director has failed to fully study the character of Manorani and what she did. There is a scene where Manorani watches a Sinhala stage play with much annoyance and on her way back home with Richard, she is shown insensitively avoiding Richard’s friend Gayan being assaulted by a mob. This demeanour does not match the actual reports and information published about Manorani. How did the director miss these records? It shows his indifference to researching background information for a film such as this. He clearly does not think that research is essential for a sharp-witted artist in creating his artwork. In his own words, he told the Anidda newspaper:

“But the information related to this is in the public domain and the challenge I had was to interpret that information in the way I wanted. I am not an investigative journalist; My job is to create a work of art. That difference should be understood and made.”

And according to the director, “I was invited to do the film in 2023. The script was written within two to three months and the shooting was planned quickly.” Thus, it is clear that there has been no time to study the inner details related to Manorani, the main character of the film, or the character’s Mannerism. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa, who published a book with two critical reviews on Handagama’s previous film ‘Alborada’, emphasises in both, that ‘Alborada’ also became weak due to the lack of proper research work’ (Lamentation of the Dawn (2022), pages 46-57).

Directors working in the biopic genre with a degree of seriousness consider it their responsibility to study deeply and construct the ‘mannerism’ of such central characters to create a superior biographical film. For example, in Kabir Khan’s 2021 film ’83’ the actor Tahir Raj Bhasin, who played the role of Sunil Gavaskar, said that it took him six months to study Sunil Gavaskar’s unique style characteristics or Mannerism.

Also, Austin Butler, the actor who played the role of Elvis Presley in the movie ‘Elvis’ directed by Buz Luhrmann and released in 2022, said in a news conference: After he started studying the character of Elvis, he became obsessed with the character, without meeting or talking to his family for nearly one year, while making the film in Australia before, during Covid and after.

‘Oppenheimer’ (2023) was written and directed by Christopher Nolan, in which Cillian Murphy plays the role of Oppenheimer. Nolan read and studied the 700-page story about Oppenheimer called ‘American Prometheus’ . It is said that it took three months to write the script and 57 days for shooting, and finally a two-hour film was created. The rejection of such intense studies by our filmmakers will determine the future of cinema in this country.

Acting is the prime aspect of a movie. The character of Manorani is performed very skillfully in the movie. But certain of her characteristics and mannerism become repetitive and in their very repetitiveness become tiresome to watch. For example, right across the film Manorani is shown smoking, drinking alcohol, sitting and thinking, going towards a window and thinking and smoking again. It would have been better if it had been edited. The audience is thereby given the impression that Manorani lives on cigarettes and whiskey. Although smoking and drinking alcohol is a common practice among some women of Manorani’s social class, it is depicted in the film so repetitively that it creates a sense of revulsion in the viewer. In the absence of close-ups and a play of light and dark, Manorani’s mental states cannot be seen in their intense three dimensionality. It is a question whether the director gave up directing and let the actress play the role of Manorani as she wished. At the beginning of the film, close-ups of Manorani appear with the titles but gradually become normal camera angles in the film. This avoids the use of close-ups of Manorani’s face to show emotion in the most shocking moments in the film. Below are some films that demonstrate this cinematic technique well.

‘Three Colours: Blue’ (1993) French, Directed by Kryzysztof Kies’lowski.

‘Memories in March’

(2010) Indian, Directed by Sanjoy Nag.

‘Manchester by the Sea’

(2016) English, Directed by Keneth Lonergan.

‘Collateral Beauty’

2016) English, Directed by David Frankel.

Certain characters appear in the film without any contribution to building Manorani’s role. Certain scenes such as the Television news, bomb explosions, dialogue scenes where certain characters interview Manorani are not integrated into the film’s narrative and feel forced. The scene with the group of hooligans in a jeep at the end of the film is like a strange tail to the film.

Richard’s sexual orientation, which is hinted at the end of the film by these thugs in the final scene, is an insult to him. It is a great disrespect to those characters to present facts without strong information analysis and to tell the inner life of those characters while presenting a real character through an artwork with real names. The director should not have done such humour and humiliation.

There is some thrill in seeing actors who resemble the main political personalities of that era playing those roles in the film. In this the film has more of a documentary than a fictional quality but it barely marks the socio-political history of this country during the period of terror in 88-89. The character of Manorani was created as a person floating in that history ungrounded, without a sense of gravity.

The film’s music and vocals are mesmerising. But unfortunately, the song ‘Puthune’ (Dearest Son), which has a very strong lyrical composition, melody and singing, is placed at the end of the film, so the audience does not know its strength. This is because the audience starts to leave the cinema as soon as the song starts, when the closing credits scrolled down. If the song had accompanied the scene on the beach where we see Manorani for the last time, the audience would have felt its strength.

Manorani’s true personality was a unique blend of charm, sensitivity, compassion, intelligence, warmth and fun, which enhanced her overall beauty, as evidenced by various written accounts of her. Art critics and historians H. W. Johnson and Anthony F. A Johnson state in their book ‘History of Art’ (2001), “Every work of art tells whether it is artistic or not. And the grammar and structure of the form will signal to us that.”

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

Features7 days ago

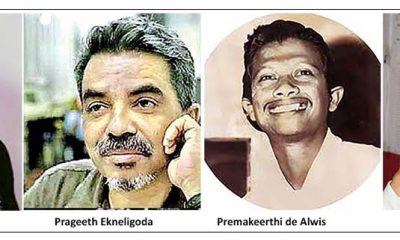

Features7 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoMahinda earn long awaited Tier ‘A’ promotion

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoExcellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoAir Force Rugby on the path to its glorious past

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSri Lanka’s first ever “Water Battery”

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRani’s struggle and plight of many mothers