Features

Almost all about Ambalangoda

By Uditha Devapriya

Photographs by Manusha Lakshan

Recalling his travels across the country, James Emerson Tennent reflects on Ambalangoda only cursorily after passing through Hikkaduwa. He writes that upon entering the area he saw, of all things, a rock python, which upon seeing the visitor uncoiled its fold and passes through the fence into the neighbouring enclosure.

Tennent recounts how, in 1587, the Portuguese, “hoping to create a diversion”, attacked several villages in this part of the coast and then shipped the peasants as slaves to India. History tells us that the residents of these areas of the country did not easily acquiesce to such treatment; so formidable were the residents of Ambalangoda that they formed the bulk of the porowakarayo or axe-wielders under the King. Paul E. Pieris tells us that these axe-wielders were so proud of their reputation that they would rather lay down their lives than abandon their stores of ammunition to the enemy.

At the turn of the 19th century, what is known today as the Galle District was made up of six divisions: Bentota-Wallawiti, Wellaboda Pattuwa, Four Gravets, Talpe Pattuwa, Gangaboda Pattuwa, and Hinidum Pattuwa. Ambalangoda belonged to the Wellaboda Pattuwa. Its reputation, as the name suggests, was for its set of ambalamas, or rest-houses: Ferguson’s Ceylon in 1913 translated this as “Rest-house village.” An alternative account relates how several fishermen, drifting in the sea after a violent storm had wrecked their sails, spotted land and shouted, “Aan balan goda!” Of course, this is highly apocryphal.

The colonial powers, especially the British, served to seal Ambalangoda’s reputation for rest-houses, so much so that every other writer from that period passing through referred to its hospitality, “excellent meals”, or “sea-bathing.” Even today, that is more or less what makes up Ambalangoda today: the people, the food, and the coast.

The colonial powers, especially the British, served to seal Ambalangoda’s reputation for rest-houses, so much so that every other writer from that period passing through referred to its hospitality, “excellent meals”, or “sea-bathing.” Even today, that is more or less what makes up Ambalangoda today: the people, the food, and the coast.

Though located in the South, certain accounts tell us that Ambalangoda was linked to the Kandyan kingdom. Again, these are highly apocryphal. Godwin Witane, for instance, has written of Kuda Adikaram, who during the Dutch era fell out with the Kandyan king and defected to the Maritime Provinces. Baptised as Costa Lapnot by the Dutch, he was put in charge of the development of these provinces, and wound up building roads, bridges, and buildings. Moving from one village to the other, he finally settled in Ambalangoda, where he devoted his career to the development of the Wellaboda Pattuwa.

Kuda Adikaram set about his task initially by turning the region into a centre for the salt trade and later by constructing canals and roads to Colombo. So prosperous did this part of Galle become with his efforts that by 1911 many centuries later, it had recorded the largest population growth over 10 years from any of the six divisions, at 15 percent.

Kuda Adikaram set about his task initially by turning the region into a centre for the salt trade and later by constructing canals and roads to Colombo. So prosperous did this part of Galle become with his efforts that by 1911 many centuries later, it had recorded the largest population growth over 10 years from any of the six divisions, at 15 percent.

E. B. Denham refers to Ambalangoda, by then converted into a Sanitary Board Town, as “a place of considerable wealth and growing importance.” At the end of the 19th century, with the Colombo Harbour replacing the Galle Harbour as the chief port in the country – a shift which led to the fall in the population growth rate from 7.9 percent in 1871-1881 to 6.3 percent in 1881-1891 – a great number of people began to leave their homes, making their way to other districts. “A comparative large number of persons from Ambalangoda” figured in this exodus, brought about by the demand for labour elsewhere, the segmentation of land in the region, and the outward migration of educated Southern youth.

It was this search for greener pastures that Martin Wickramasinghe epitomised in the character of Piyal in Gamperaliya, and it followed, as Kumari Jayawardena notes, a decline in primordial attachments to caste-based hierarchies. The South was, in other words, breaking apart, and this process of breaking apart was felt acutely in the more urbanised sections of Galle: Bentota, Balapitiya, and Ambalangoda.

It was this search for greener pastures that Martin Wickramasinghe epitomised in the character of Piyal in Gamperaliya, and it followed, as Kumari Jayawardena notes, a decline in primordial attachments to caste-based hierarchies. The South was, in other words, breaking apart, and this process of breaking apart was felt acutely in the more urbanised sections of Galle: Bentota, Balapitiya, and Ambalangoda.

Not everyone welcomed these developments. Some viewed then with alarm, since the province had by the 20th century gained a notorious reputation for lawlessness: “The growing independence of the villagers… has been accompanied by a steady decline in the power and influence of the headman” (Wright 1907: 753).

Four years later, however, the region was making a more favourable impression on outsiders, and eventually the “spirit of lawlessness” that had reigned until then all but completely disappeared. In that scheme of things the native of Galle was singled out for praise, “for his enterprise and spirit of adventure” (Denham 1912: 81).

Moreover, by now Wellaboda Pattuwa was recording a very high outward migration from any part of the Galle district. To an extent this had to do with the socioeconomic changes making themselves felt across the island. Not surprisingly, it led to the inhabitants of the Deep South to be singled out and characterised as cunning, unyielding, dubious, wherever they travelled. That reputation has a history of its own going back to the 16th century, when the southwest was turned by the Portuguese and Dutch into a cinnamon outpost, leading to some of the most aggressive rebellions ever recorded in the region.

Today the six divisions have given way to 19, with the result that what almost were constituent parts of Ambalangoda have become autonomous. Consequently, Elpitiya and Karandeniya, which are as much a part of Ambalangoda as Ambalangoda is a part of Galle, have turned into separate electoral divisions, and though they can’t be separated, they have formed an identity of their own. Four things, however, bring them together: the people, the food, the cinnamon, and of course the cultural and religious rituals.

Today the six divisions have given way to 19, with the result that what almost were constituent parts of Ambalangoda have become autonomous. Consequently, Elpitiya and Karandeniya, which are as much a part of Ambalangoda as Ambalangoda is a part of Galle, have turned into separate electoral divisions, and though they can’t be separated, they have formed an identity of their own. Four things, however, bring them together: the people, the food, the cinnamon, and of course the cultural and religious rituals.

Taking its people into consideration, the Ambalangoda identity has been, and is, caste-based. While caste is a non-entity in these regions, it is also not to be invoked or spoken of casually. In that sense, what otherwise would have unified Ambalangoda and its neighbour, Balapitiya, instead fragmented it: that is what bewildered Bryce Ryan when he observed in 1953 that while Ambalangoda-Balapitiya remained a single electoral district, it elected two people to Parliament: from Ambalangoda a karava member, from Balapitiya a salagama member (both strong leftists, since the UNP was considered to be a “Govigama club”). While Balapitiya remained the outpost of the de Zoysas, de Abrews, and Rajapakses, Ambalangoda remained a home to the Arachchiges, Hettiges, and Patabendiges.

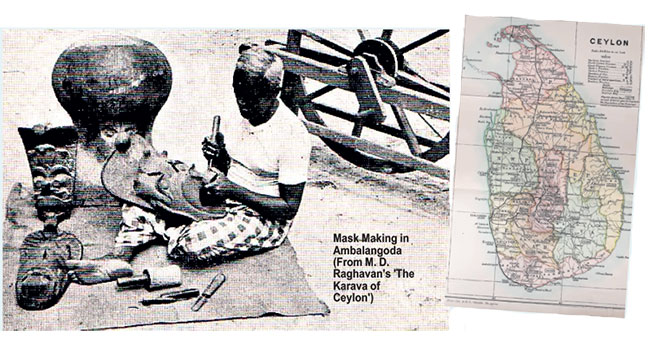

In terms of food and cinnamon and rituals, of course, nothing much needs to be said, except that they are popular even now. The rituals continue to be as unique to the region as the rituals of the interior are to the former Kandyan provinces: with their mishmash of South Indian and folk cultures, kolam, rukada natum, and ves muhunu are the most profound and acute testament to the influence of cultural fusion in the island.

“Conspicuous by its absence in the Kandyan hill country”, kolam was associated so much with Ambalangoda that it “virtually ceased to exist” elsewhere (Raghavan 1961: 125). I have come across a kolam item once. I can’t say I understood it, but it mesmerised me: with its strongly emotional undercurrents, it is a truly rural entertainment. What, then, explains the differences between such art forms and those found higher up in Kandy?

We can only guess.

Perhaps the relatively serene life in the interior contributed to a culture of aristocratic art aimed at the invocation of beauty and prosperity, while in the Maritime Provinces, particularly in areas like Ambalangoda, the people’s harrowing encounters with colonialism turned art into a tool, not for invoking beauty, but for appeasing evil. Thus, as opposed to the daha ata vannama, the low country bred the daha ata sanniya: the one full of regal splendour, the other full of scatological farce.

Perhaps the relatively serene life in the interior contributed to a culture of aristocratic art aimed at the invocation of beauty and prosperity, while in the Maritime Provinces, particularly in areas like Ambalangoda, the people’s harrowing encounters with colonialism turned art into a tool, not for invoking beauty, but for appeasing evil. Thus, as opposed to the daha ata vannama, the low country bred the daha ata sanniya: the one full of regal splendour, the other full of scatological farce.

All this distinguishes the people of the South from the people of Kandy: crude at one level, brutally honest at another. Perhaps this was what repelled the writers of the 20th century, and made them come up with the stereotype of the Southerner as cunning and deceitful. That in turn may have spurred officials to attribute to them a rebellious and violent streak. Whatever the reasons for it may be, the stereotype has endured to this day.

Today, of course, there are a great many people hailing from Ambalangoda and Balapitiya who have made a name for themselves. Norah Roberts writes about them in her beautiful account of the region, Galle: As Quiet As Sleep. We can add to her list. But it’s not just those famous people we know about who have found a second home among us: it’s also every other person you come across every other day, who has migrated from these corners of the South. Scratch these people and you can trace them to Galle; scratch them even harder and you can trace them to Ambalangoda and Balapitiya, well beyond Bentara.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

Features

Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs

Certain songs become ever-present every December, and with Christmas just two days away, I thought of highlighting the Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs.

The famous festive songs usually feature timeless classics like ‘White Christmas,’ ‘Silent Night,’ and ‘Jingle Bells,’ alongside modern staples like Mariah Carey’s ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You,’ Wham’s ‘Last Christmas,’ and Brenda Lee’s ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.’

The following renowned Christmas songs are celebrated for their lasting impact and festive spirit:

* ‘White Christmas’ — Bing Crosby

The most famous holiday song ever recorded, with estimated worldwide sales exceeding 50 million copies. It remains the best-selling single of all time.

* ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’ — Mariah Carey

A modern anthem that dominates global charts every December. As of late 2025, it holds an 18x Platinum certification in the US and is often ranked as the No. 1 popular holiday track.

Mariah Carey: ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’

* ‘Silent Night’ — Traditional

Widely considered the quintessential Christmas carol, it is valued for its peaceful melody and has been recorded by hundreds of artistes, most famously by Bing Crosby.

* ‘Jingle Bells’ — Traditional

One of the most universally recognised and widely sung songs globally, making it a staple for children and festive gatherings.

* ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’ — Brenda Lee

Recorded when Lee was just 13, this rock ‘n’ roll favourite has seen a massive resurgence in the 2020s, often rivaling Mariah Carey for the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100.

* ‘Last Christmas’ — Wham!

A bittersweet ’80s pop classic that has spent decades in the top 10 during the holiday season. It recently achieved 7x Platinum status in the UK.

* ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ — Bobby Helms

A festive rockabilly standard released in 1957 that remains a staple of holiday radio and playlists.

* ‘The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)’— Nat King Cole

Known for its smooth, warm vocals, this track is frequently cited as the ultimate Christmas jazz standard.

Wham! ‘Last Christmas’

* ‘It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year’ — Andy Williams

Released in 1963, this high-energy big band track is famous for capturing the “hectic merriment” of the season.

* ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ — Gene Autry

A beloved narrative song that has sold approximately 25 million copies worldwide, cementing the character’s place in Christmas folklore.

Other perennial favourites often in the mix:

* ‘Feliz Navidad’ – José Feliciano

* ‘A Holly Jolly Christmas’ – Burl Ives

* ‘Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!’ – Frank Sinatra

Let me also add that this Thursday’s ‘SceneAround’ feature (25th December) will be a Christmas edition, highlighting special Christmas and New Year messages put together by well-known personalities for readers of The Island.

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka, Romania discuss illegal recruitment, etc.