Features

A Tragedy of Relying on Misinformation

Import Ban on Synthetic Fertilizers –

by Buddhi Marambe,

Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya

The ban on importation of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides was imposed on May 6, 2021 through the Extraordinary Gazette Notification No 2226/48. This was one of the 20 activities approved by the Cabinet of Ministers under the theme “Creating a Green Socio-economy with Sustainable Solutions for Climate Change”. The theme carries a long term noble objective. However, the approach suggested for achieving the objective in the agriculture sector is not at all practical, even to maintain the current levels of crop production and productivity in the country thus, threatening food security.

Use of organic matter as a soil conditioner, and a supplementary nutrient source to a certain extent, have always been encouraged by many and practiced by farmers at different levels with various objectives. Organic farming is a specialty practice with product and process certification. It has a good but niche export market and also a promising foreign exchange earner. It is heartening to see that organic fertilizer production and compost production are taking place at a mass scale in the country, in response to this policy decision. However, even with the novel technologies, organic fertilizer and/or compost alone would not suffice in providing the required nutrition to plants at the correct time and quantities. A high crop productivity could be achieved when appropriate strategies are used to match the patterns of supply of nutrients from fertilizer (organic or mineral) and absorption of nutrients by plants/crops. This aspect has been much deliberated and hence, I will not elaborate on the same further.

We have now learned that the decision to ban import of agrochemicals was made due to speculation that the farmers in many parts of the country suffer from many Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) including kidney disease and also that the serious damages done to the environment with the use of mineral fertilizers. Furthermore, we were also informed that the government spends huge amounts of foreign exchange annually on mineral fertilizer imports, inferring that there is a foreign currency issue that has also set the base for this decision. The author of this article strongly believe that the decision to ban agrochemicals has been taken on misinformation provided to His Excellency the President. Hence, the correct facts regarding the mineral fertilizer and their utilization in Sri Lanka are presented in this article to debunk the unscientific justifications made by some individuals and groups that would probably have led to the policy directive.

Fertilizer Imports and use in Sri Lanka

The Kethata Aruna fertilizer material subsidy programme was introduced in 2005 and dismantled in 2016-2017 replaced by a cash subsidy. The fertilizer material subsidy was re-introduced thereafter since 2018 in different forms. The import of mineral fertilizers is governed by the Regulation of Fertilizer Act No. 68 of 1988. This is under the purview of the National Fertilizer Secretariat (NFS). It must be noted that all quantities of fertilizer imported are decided by the NFS based on the advice and recommendations of the respective state agencies, i.e. Department of Agriculture, Research Institutes responsible for tea, rubber, coconut, sugarcane, etc. The quantities to be imported are decided annually considering the existing extent (for perennial crops) and anticipated extent (e.g. annual food crops) of cultivation, considering the fertilizer recommendations given by state agencies based on crop-nutrient requirements.

For example, according to the NFS, the anticipated paddy cultivation in Sri Lanka in 2021 (both Yala and Maha seasons together) is 1.3 million ha and the required quantity of fertilizer to be imported is 247,000 mt of Urea, 61,000 mt of Triple Super Phosphate (TSP) and 74,000 mt of Muriate of Potash (MOP). As per government regulations, all paddy fertilizer (subsidized fertilizer) can only be imported and distributed through the government-controlled mechanism. Excluding paddy, the anticipated fertilizer import in 2021 to provide required nutrients to other food crops and perennial/plantation crops for an estimated extent of 1.47 million ha amounts to 298,983 mt of Urea, 102,928 mt of TSP and 243,743 mt of MOP. There are other types of fertilizer also imported under the licenses issued by NFS. Further, excluding the subsidized fertilizer for paddy, the NFS issues permits to the private sector to import fertilizer for other crops on an agreed quota system.

It is important to note that no individual or agency in Sri Lanka (government-owned or private sector) can import fertilizer without an import permit issued by the NFS. The import permits are issued based on the actual crop requirements and anticipated cultivated extents. Therefore, it is clear that the quantity of fertilizer imported to Sri Lanka is not done on an ad hoc basis, but on a clear scientific methodology. Farmers should receive fertilizer at quantities decided by the NFS as recommended by the state institutions, and up to what is required by the country – not in excess. When this is done following an accepted procedure, there is no point in arguing that Sri Lanka is importing more “chemical”/synthetic fertilizers than what is required in a given year. However, many policy makers and professionals still blame farmers for overusing fertilizer, which theoretically cannot be true as the fertilizer quantities are imported based on the actual crop requirements as estimated by the state agencies.

It is important to note that no individual or agency in Sri Lanka (government-owned or private sector) can import fertilizer without an import permit issued by the NFS. The import permits are issued based on the actual crop requirements and anticipated cultivated extents. Therefore, it is clear that the quantity of fertilizer imported to Sri Lanka is not done on an ad hoc basis, but on a clear scientific methodology. Farmers should receive fertilizer at quantities decided by the NFS as recommended by the state institutions, and up to what is required by the country – not in excess. When this is done following an accepted procedure, there is no point in arguing that Sri Lanka is importing more “chemical”/synthetic fertilizers than what is required in a given year. However, many policy makers and professionals still blame farmers for overusing fertilizer, which theoretically cannot be true as the fertilizer quantities are imported based on the actual crop requirements as estimated by the state agencies.

If the correct quantities of fertilizer are imported and their distribution is regulated (assuming no illegal entry of fertilizer to the country), the claims for overuse of fertilizer should not have arisen. Further, there should be false alarms ringing to politicians and decision makers that undue quantities of fertilizer has been imported with a huge pressure on foreign exchange drain, and causing severe impacts on the environment. Such false alarms would also have provided a window of opportunity for some to create the “fertilizer demon”.

Once the fertilizer or any other agricultural input is heavily subsidized, their misuse is the most highly likely (mal)practice. In this context, if the state agencies and the NFS have done a fairly accurate estimate for the fertilizer requirement and imports, the best option available would be to remove the fertilizer subsidy (at once or in a phased-out manner) and make “chemical” and organic fertilizers readily available in the market allowing the farmers to take a judicious decision on the fertilizer use on their own. Farmers also need proper training on the judicious use of “chemical” fertilizers with organic matter, i.e. integrated plant nutrient systems (IPNS), and obviously pesticides. Without such well-targeted capacity building, it is not wise to put the blame on the farming community for misusing or overusing agrochemicals and thereby polluting the environment.

Furthermore, some scientists and professionals claim that Sri Lanka uses the highest quantity of fertilizer among those in Asia (or South Asia). The latest FAO statistics available for all countries clearly indicate the low rate of fertilizer use in Sri Lanka (Figure 1), except for few years. Regarding pesticide use, too, Sri Lanka stands at very low rates of application. Hence, the popular notion of heavy use of fertilizers leading to health hazards and environmental pollution is an erroneous conclusion drawn without considering the scientific facts.

Eco-friendly fertilizer use

Organic amendments in agriculture is not an alien practice to our farmers. The IPNS in crop production; i.e. the use of organic matter with “chemical” fertilizers, has been recommended since time immemorial to improve the fertilizer and nutrient use efficiency and to minimize environmental pollution caused by leaching. The Department of Agriculture (DOA) has formally promoted the adoption of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) to minimize any misuse of agrochemicals, since 2015.The GAP programme has started gaining momentum in 2020. Prior to the current policy directive, the Ministry of Agriculture even had plans to distribute organic fertilizers produced by different private companies to selected paddy growers during 2021 Yala season, together with “chemical” fertilizer. The proportionate allocation of fertilizer for this IPNS was 30% organic fertilizer, and 70% urea, 50% TSP and 70% MOP as per recommendation of the DOA. Similar proportions were also used in the case of bio-fertilizers. This was an excellent initiative. However, the current policy directive will derail this good practice and would create disastrous impacts on crop production.

Figure 1.

Fertilizer use (kg per ha of cropland) in developed and developing countries. Data labels are for the year 2018 (Source: FAOSTAT)

Low quality fertilizer imports

The Sri Lanka Standards Institute (SLSI) has set up standards for the “chemical” and organic fertilizers to be used in Sri Lanka. The NFS relies on such standards, which are adopted for any fertilizer used in Sri Lanka (imported or locally produced). The sparkling revelation made by the Hon. Minister of Agriculture, which also appeared in the Government Audit Report of 2020 which says that 55 fertilizer analysis reports have been tampered to allow inferior quality fertilizers to be released in Sri Lanka. Release of 12,000 mt of imported TSP in 2020 having heavy metals such as lead (Pb) contents higher than the limit set by SLSI (maximum Pb content allowed in TSP is 30 ppm) was reported in electronic and social media, and also raised at the Parliament causing serious concerns over the mishandling of state affairs by certain officials. Hats off to the Hon. Minister of Agriculture who took stern punitive action against some officials for tampering the analytical reports of the fertilizer samples.

Recently, we also heard that organic fertilizer has been imported without proper approvals. Any plant-based organic fertilizer requires the approval and a permit of the DG of the DOA under the Plant Protection Act No 35 of 1999. We also heard that such imports have been done in the past, which should not have been allowed due to multi-folded negative impacts than what is even speculated against agrochemicals. The efforts made by officers of the DOA and the Sri Lanka Customs, and no signs of political interference in releasing the imported consignment is noteworthy and require special commendations.

All such incidents indicate that the well-articulated fertilizer regulatory process has been breached by some people with vested interests. These are daylight robberies of government (people’s) money and efforts to rape the environment (similar to misuse of any other agricultural inputs). The penalties have been imposed in some cases but it is high time that openings for mal-practices be sealed-off so that even in the future, import of any type of fertilizers is stringently governed.

The case of non-communicable diseases

Agrochemicals are generally considered as the causal factors for many of the non-communicable diseases (NCDs), especially the chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology (CKDu). Such unproven ideology has been forced into minds of people who are suffering from the disease. Some even dubbed CKDu as ‘Agricultural kidney disease’. This propaganda campaign has brainwashed not only the unfortunate patients, but also the general public and policy makers and thus, creating fear against an important agricultural input.

In those claims, nutrients are probably not targeted as the causal factor for NCDs. For example, both mineral and organic fertilizers provide the essential plant nutrient “Nitrogen” in the form Nitrate (NO3–) or Ammonium (NH4+) ions to be taken up by plants. Further, amino acid supplements providing 13-19% nitrogen can also be taken up by plants directly. The loss of Nitrates in the ecosystems, especially polluting ground water, can be minimized by split application of fertilizer (which is the recommended practice) and with the application of organic matter (manure, fertilizer or composts) as soil amendments. The organic amendments have limited plant nutrient supply (e.g. 1-3.5% N, or rarely up to 6% depending on the source). Lack of soil organic matter (e.g. sandy soils) will create a negative scenario as observed in isolated incidents such as Kalpitiya area. Hence, the popular argument on the impact of fertilizer on human health and environment issues could mainly be focused on the potential contaminants in fertilizers, such as heavy metals.

Nitrogen being the most difficult element to tackle in nature, let me take an example for urea. The maximum limits allowed by the SLS standards for Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) for urea fertilizer used in Sri Lanka is 0.1, 0.1 and 0.1 ppm, respectively. As for solid organic fertilizers the corresponding values are 3, 1.5 and 30 ppm, respectively (SLS 1704:2021). This indicates the danger that could arise from application of solid organic fertilizer with the objective of providing nitrogen to the crops. Extremely low and stringent heavy metal limits have been adopted for urea as there is hardly any chance for such contamination, but the maximum allowable limits for such elements in solid organic fertilizers are higher owing to higher potential for contamination. If the municipal solid waste is used as the source to produce composts for agricultural land, then the maximum allowable limits for As, Cd and Pb are 5, 3 and 150 ppm (SLS 1634:2019), respectively. This needs no further explanation to prove the fact that organic fertilizer targeting Nitrogen could pollute the environment at a higher level than urea.

The popular talk on “Agrochemicals as a causal factor for rising incidence of cancer in Sri Lanka” has surfaced again. I am not a medical professional to provide details on such. However, as per Figure 1, the amount of fertilizer added per ha of cropland in 2018 in Australia was 86 kg, Bangladesh 318 kg and Sri Lanka 138 kg. But, the statistics presented by GLOBOCAN 2020 revealed that five-year prevalence in cancer as a proportion for 100,000 population in Australia is 3,172, Bangladesh 164, and Sri Lanka 354. I will leave it with the learned readers to draw conclusions.

The “demon” created in people’s mind with respect to use of fertilizer and its impact on NCDs such as CKDu was comprehensively refuted recently by the Chairman of the National Research Council (NRC) of Sri Lanka, appearing in a popular TV discussion. The Chairman/NRC clearly stated that the most recent research completed under the funding from NRC has concluded that not drinking adequate volumes of water and the high fluoride content in ground water as the two major causal factors for the CKDu in Anuradhapura area. He further stated that the disease is not due to heavy metals and that this information has been provided to the Ministry of Health.

Need for evidence-based policy making

National policies need to be set based on evidence. Policies driven by advice from those who want their whims and fancies to be realized at the expense of national budget will result in detrimental and irreversible impact on the national economy. Further, the spread of unproven and non-scientific ideologies across the society have already made complete change in focus of the efforts made to find solutions to major issues in the Sri Lankan society, including finding causal factors for human health related problems such as CKDu. Many intellectuals have alarmed that the import ban on “chemical” fertilizers would lead to food shortages and high food prices. In this context, Sri Lanka is likely to import a major portion of basic food needs such as rice, as experienced by Bhutan in their failed attempt to become the first organic country by 2020, adding a huge burden to the government treasury.

The fear generated on agrochemicals thus, seems to be due to chemophobia (irrational fear of chemicals) of some people, who have unduly fed the same into the authorities. His Excellency and the Cabinet of Ministers should not fall prey to ideologies spread by some people that could have unprecedented negative effects, in making decisions in relation to the country’s economy. It is still not late to revisit the decision to ban the import of agrochemicals. Being misinformed is more dangerous than being not informed.

Features

The hollow recovery: A stagnant industry – Part I

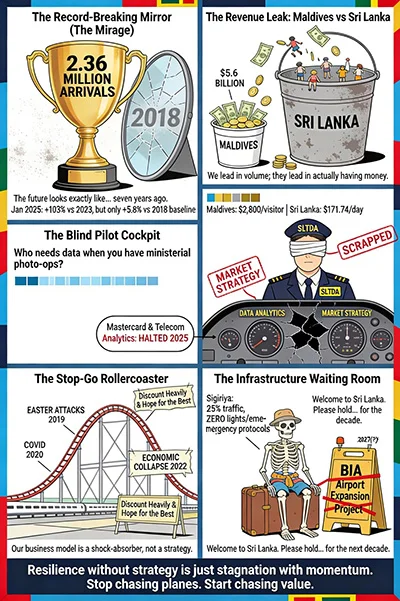

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

But scratch beneath the surface and what emerges is not a success story but a cautionary tale of an industry that has mistaken survival for transformation, volume for value, and resilience for strategy.

Problem Diagnosis: The Mirage of Recovery

Yes, Sri Lanka welcomed 2.36 million tourists in 2025, marginally above the 2.33 million recorded in 2018. This marks a full recovery from the consecutive disasters of the Easter attacks (2019), COVID-19 (2020-21), and the economic collapse (2022). The year-on-year growth looks impressive: 15.1% above 2024’s 2.05 million arrivals.

But context matters. Between 2018 and 2023, arrivals collapsed by 36.3%, bottoming out at 1.49 million. The subsequent “rebound” is simply a return to where we were seven years ago, before COVID, before the economic crisis, even before the Easter attacks. We have spent six years clawing back to 2018 levels while competitors have leaped ahead.

Consider the monthly data. In 2023, January arrivals were just 102,545, down 57% from January 2018’s 238,924. By January 2025, arrivals reached 252,761, a dramatic 103% jump over 2023, but only 5.8% above the 2018 baseline. This is not growth; it is recovery from an artificially depressed base. Every month in 2025 shows the same pattern: strong percentage gains over the crisis years, but marginal or negative movement compared to 2018.

The problem is not just the numbers, but the narrative wrapped around them. SLTDA’s “Year in Review 2025” celebrates the 15.6% first-half increase without once acknowledging that this merely restores pre-crisis levels. The “Growth Scenarios 2025” report projects arrivals between 2.4 and 3.0 million but offers no analysis of what kind of tourism is being targeted, what yield is expected, or how market composition will shift. This is volume-chasing for its own sake, dressed up as strategic planning.

Comparative Analysis: Three Decades of Standing Still

The stagnation becomes stark when placed against Sri Lanka’s closest island competitors. In the mid-1990s, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, started from roughly the same base, around 300,000 annual arrivals each. Three decades later:

Sri Lanka: From 302,000 arrivals (1996) to 2.36 million (2025), with $3.2 billion

Maldives: From 315,000 arrivals (1995) to 2.25 million (2025), with $5.6 billion

The raw numbers obscure the qualitative difference. The Maldives deliberately crafted a luxury, high-yield model: one-island-one-resort zoning, strict environmental controls, integrated resorts layered with sustainability credentials. Today, Maldivian tourism generates approximately $5.6 billion from 2 million tourists, an average of $2,800 per visitor. The sector represents 21% of GDP and generates nearly half of government revenue.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, has oscillated between slogans, “Wonder of Asia,” “So Sri Lanka”, without embedding them in coherent policy. We have no settled model, no consensus on what kind of tourism we want, and no institutional memory because personnel and priorities change with every government. So, we match or slightly exceed competitors in arrivals, but dramatically underperform in revenue, yield, and structural resilience.

Root Causes: Governance Deficit and Policy Failure

The stagnation is not accidental; it is manufactured by systemic governance failures that successive governments have refused to confront.

1. Policy Inconsistency as Institutional Culture

Sri Lanka has rewritten its Tourism Act and produced multiple master plans since 2005. The problem is not the absence of strategy documents but their systematic non-implementation. The National Tourism Policy approved in February 2024 acknowledges that “policies and directions have not addressed several critical issues in the sector” and that there was “no commonly agreed and accepted tourism policy direction among diverse stakeholders.”

This is remarkable candor, and a damning indictment. After 58 years of organised tourism development, we still lack policy consensus. Why? Because tourism policy is treated as political property, not national infrastructure. Changes in government trigger wholesale personnel changes at SLTDA, Tourism Ministry, and SLTPB. Institutional knowledge evaporates. Priorities shift with ministerial whims. Therefore, operators cannot plan, investors cannot commit, and the industry lurches from crisis response to crisis response without building structural resilience.

2. Fragmented Institutional Architecture

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

No single institution owns yield. No one is accountable for net foreign exchange contribution after leakages. Quality standards are unenforced. The tourism development fund, 1% of the tourism levy plus embarkation taxes, is theoretically allocated 70% to SLTPB for global promotion, but “lengthy procurement and approval processes” render it ineffective.

Critically, the current government has reportedly scrapped sophisticated data analytics programmes that were finally giving SLTDA visibility into spending patterns, high-yield segments, and tourist movement. According to industry reports in late 2025, partnerships with entities like Mastercard and telecom data analytics have been halted, forcing the sector to fly blind precisely when data-driven decision-making is essential.

3. Infrastructure Deficit and Resource Misallocation

The Bandaranaike International Airport Development Project, essential for handling projected tourist volumes, has been repeatedly delayed. Originally scheduled for completion years ago, it is now re-tendered for 2027 delivery after debt restructuring. Meanwhile, tourists in late 2025 faced severe congestion at BIA, with reports of near-miss flights due to immigration and check-in bottlenecks.

At cultural sites, basic facilities are inadequate. Sigiriya, which generates approximately 25% of cultural tourist traffic and charges $36 per visitor, lacks adequate lighting, safety measures, and emergency infrastructure. Tourism associations report instances of tourists being attacked by wild elephants with no effective safety protocols.

SLTDA Chairman statements acknowledge “many restrictions placed on incurring capital expenditure” and “embargoes placed not only on tourism but all Government institutions.” The frank admission: we lack funds to maintain the assets that generate revenue. This is governance failure in its purest form, allowing revenue-generating infrastructure to decay while chasing arrival targets.

The Stop-Go Trap: Volatility as Business Model

What truly differentiates Sri Lanka from competitors is not arrival levels but the pattern: extreme stop-go volatility driven by crisis and short-term stimulus rather than steady, strategic growth.

After each shock, the industry is told to “bounce back” without being given the tools to build resilience. The rebound mechanism is consistent: currency depreciation makes Sri Lanka “affordable,” operators discount aggressively to fill rooms, and visa concessions attract price-sensitive segments. Arrivals recover, until the next shock.

This is not how a strategic export industry operates. It is how a shock-absorber behaves, used to plug forex and fiscal holes after each policy failure, then left exposed again.

The monthly 2023-2025 data illustrate the cycle perfectly. Between January 2018 and January 2023, arrivals fell 57%. The “recovery” to January 2025 shows a 103% jump over 2023, but this is bounce-back from an artificially depressed base, not structural transformation. By September 2025, growth rates normalize into the teens and twenties, catch-up to a benchmark set six years earlier.

Why the Boom Feels Like Stagnation

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Because input costs, energy, food, debt servicing, have risen faster than room rates. The rupee’s collapse makes Sri Lanka look “affordable” to foreigners, but it quietly transfers value from domestic suppliers and workers to foreign visitors and lenders. Hotels fill rooms at prices that barely cover costs once translated into hard currency and adjusted for inflation.

Growth is fragile and concentrated. Europe and Asia-Pacific account for over 92% of arrivals. India alone provides 20.7% of visitors in H1 2025, and as later articles in this series will show, this is a low-yield, short-stay segment. We have built recovery on market concentration and price competition, not on product differentiation or yield optimization.

There is no credible long-term roadmap. SLTDA’s projections focus almost entirely on volumes. There is no public discussion of receipts-per-visitor targets, market composition strategies, or institutional reforms required to shift from volume to value.

The Way Forward: From Arrivals Theater to Strategic Transformation

The path out of stagnation requires uncomfortable honesty and political courage that has been systematically absent.

First, abandon arrivals as the primary success metric. Tourism contribution to economic recovery should be measured by net foreign exchange contribution after leakages, employment quality (wages, stability), and yield per visitor, not by how many planes land.

Second, establish institutional continuity. Depoliticize relevant leaderships. Implement fixed terms for key personnel insulated from political cycles. Tourism is a 30-year investment horizon; it cannot be managed on five-year electoral cycles.

Third, restore data infrastructure. Reinstate the analytics programs that track spending patterns and identify high-yield segments. Without data, we are flying blind, and no amount of ministerial optimism changes that.

Fourth, allocate resources to infrastructure. The tourism development fund exists, use it. Online promotions, BIA expansion, cultural site upgrades, last-mile connectivity cannot wait for “better fiscal conditions.” These assets generate the revenue that funds their own maintenance.

Resilience without strategy is stagnation with momentum. And stagnation, however energetically celebrated, remains stagnation.

If policymakers continue to mistake arrivals for achievement, Sri Lanka will remain trapped in a cycle: crash, discount, recover, repeat. Meanwhile, competitors will consolidate high-yield models, and we will wonder why our tourism “boom” generates less cash, less jobs, and less development than it should.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition