Opinion

A singular modern Lankan mentor – Part III

by Laleen Jayamanne and Namika Raby

Gananath Obeysekere: In search of Buddhist conscience

(Baudha Hurdasakshiya Soya)

(Part II of this article appeared in The Island on Monday – 03)

Tissa Ranasinghe’s and Gananath’s Kannagi

Gananath’s Pattini book has a mysterious blue-black cover with an icon of Kannagi in Bronze sculpted by Lanka’s foremost Modernist sculptor Tissa Ranasinghe, commissioned by Gananath. What Appadurai termed Lanka’s links with ‘Indic culture’ is encapsulated in this image of the heroic figure Kannagi from the Tamil epic, striking a gesture of mourning for her husband Kovalan, unjustly killed by the king of Madurai. She kneels with her arms held raised around her head in the familiar triangular formation suggestive of the aniconic representation of the Yoni (an emblematic civilisational gesture of great iconic strength and power, in the Bronze lineage of India, which stretches back to the little bronze figurine of The Dancing Girl of Monhenjodaro itself), even as she laments the injustice. And those of us who know the legend also see that her left breast is missing. Kannagi, it is told, tore her breast and hurled it at the city of Madurai, setting it on fire with her righteous anger! Together, Gananath and Tissa have presented Kannagi in a most generative posture and gesture for the cover of the book on the Sinhala Pattini cult, the only Mother goddess of the Sinhala folk, borrowed from the Tamil Epic, to assuage and heal Sinhala male sexual anxieties and group trauma. This marvelous collaboration between Lanka’s celebrated Modernist Sculptor and Anthropologist was a multivalent, therapeutic intervention into Lanka’s cyclical interethnic violence. The book was published in 1984, one year after the state sponsored pogram against Tamils in July ‘83. Tissa’s modernist Kannagi demonstrates how an archaic ‘Maternal Archetype’ can be creatively mobilised by an artist, to express contemporary predicaments without diluting her orginal power and affective vitality magnified by the use of bronze, a resonant civilisational material.

Pattini is the Sinhala Buddhist incarnation of the Tamil heroic Kannagi and as far as I can tell she appears not to have the iconographic attributes of heroic rage and righteous anger which Kannagi embodies in the Tamil Epic. Kannagi is the step mother of Manimekalai who became a Buddhist nun, according to legend. Is it the case that Pattini is without progeny and so, as a Mother Goddess, rather like the West Asian mother Goddesses who were also virgins? As a girl, my mother and I were devoted to rituals of Mother Mary (mother of Jesus), also known as the Virgin-Mary from, let’s not forget, West Asia (in historic Palestine).

Professor Sunil Ariyaratne’s 2016 film Pattini, warrants a passing comment or two in this context as an example of the institutional consolidation of Neo-Liberal capitalist extraction and commodification of the residual vitality and power of the perennial syncretic Folk traditions of Lanka. It is a neo-traditionalist extravaganza in the genre of nostalgic revival of ‘the Sinhala-Buddhist Folk Heritage of Lanka’ which flourished recently with much fanfare and state patronage as a ‘Rajapaksha genre’. The film deals with the Kannagi legend just so as to reduce it to reinforcing the Sinhala-Buddhist ideology of purity and virginity for women through the exemplary tale of ‘the pure wife’ Kannagi and her step-daughter Manimekala, who becomes a Tamil Buddhist. Her dearest wish is to be reborn as a male so that she can indeed aspire to become a Buddha. The emphasis is on the preservation of virginity (Pathiwatha), and the enthroning of male sexuality as the route to attaining Buddhahood. The mythic epic figure of Kannagi who in her rage enacts heroic justice in the Tamil epic is converted into a parabolic emblem of virginal purity.

A Humanist Education

Gananath’s education is a strand very comprehensively covered in the film, a source of his immense openness to the world of ideas and refusal to accept them on authority without critical evaluation. The film opens at Gananath’s home in Kandy which he shares with Professor Ranjini Obeysekere who appears with her vibrant intellect and grace and ends there too. The couple are shown warmly welcoming the film crew to their house as they have done over their long engagement with numerous students, as they did with me both in Kandy and the US when I was tangled up and blue. It is worth remembering here that Ranjini is the Editor in Chief of the magnificent multi-volume translation project of the Jataka Tales into English, published just last year. It is only now that I can see how deeply Ranjini and Gananath’s scholarship is in conversation with each other.

The account of Ranjini and Gananath’s meeting at Peradeniya University while studying English Literature with Professor E.F.C. Ludowyk is one of the highlights of the film for me. Ranjini acted in the plays directed by Ludowyck and they studied English Literature at honours level together. Interestingly, though Gananath followed the Dram Soc activities on campus, he didn’t participate in any of them, his interest being elsewhere. He says, whenever he could he got onto a bus or train and travelled to distant villages to talk to villagers and monks and tape their songs (kavi). Gananath says that Ludowyck was the best teacher he has ever met and that he was responsible for directing him at every key juncture of his undergraduate life and soon after when making the unusual choice of going to a US graduate school, refusing a scholarship to Cambridge because of colonial history. Gananath’s brilliant textual analysis and exegesis of texts in Sinhala of myths and legends, especially the complex corpus of the Gajabahu legend, owes a great deal to the textual training he received from Ludowyck in ‘Practical Criticism’. We are all beneficiaries of this tradition of Literary Criticism which was part of the training we received in English Lit in old Ceylon and now continued by scholars such as Professor of English, Sumathy Sivamohan and others. Ranjini tells us that it was Ludowyck who collected Rs 10,000 from ten of his friends and handed it to Gananath to go travel the country and do what he wished soon after he graduated with English Honours. All he was asked to do was to write and thank his benefactors. So, it’s this tradition of mentorship and duty of care that Gananath and Ranjini have practiced with their own students during their long working life at American Universities.

A Counter Archive of a People’s Literature, Painting and Ritual

Though I was familiar with some of Gananath’s writing and studied a couple for the film I made, there is a major topic of his research which I didn’t know anything about and as such this film has provided an important learning experience for me. In drawing from the local non-canonical texts preserved in Temples, libraries and archives, which are written, in Sinhala by the folk and as such are anonymous, not by scholar monks in Pali, the language of high learning, Gananath has been able to piece together stories, legends of migrations from India, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and the ways in which some of these waves of migrants have been incorporated into the folk Buddhist body politic and culture. The gist of which is the seemingly heretical idea (an affront to Sinhala exceptionalism and their sense of manifest destiny as ‘pure Ariya’ Sinhala-Buddhists claiming to be the only real Lankans), that at one time, all people who call themselves Sinhala in Lanka did come from India and were indigenised through various practices and this happened in waves of migration over long periods of time. This section draws from the folk archive of poetry, ritual and Temple murals and legends such as the complex Gajabahu Myth, that bear witness to these processes of migration and acculturation, to make the case for the existence of robust muti-ethnic, diverse communities dotting the island. The legendary folk tales and rituals were, he says, imaginative, fictionalised, poetic expressions of folk memory of these migratory events, not ‘false’ accounts.

Here I want to cite a longish relevant passage from Professor Patrick Olivelle’s highly acclaimed book, Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King. Ramchandra Guha, the editor of the series called ‘Indian Lives‘ of which this is the first, says of the Lankan Olivelle that, ‘he is one of the greatest living scholars of Ancient India’. Here’s Olivelle’s argument, on the familiar opposition between History and Legend, which supports Gananath’s theoretical move with practical consequences for how we understand ourselves as Lankans.

“In a seminal remark, the historian Robert Lingat notes: ‘There are two Ashokas—the historical Ashoka whom we know through his inscriptions, and the legendary Ashoka, who is known to us through texts of diverse origin, Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan. Although essentially correct, there are two problems with Lingat’s assessment.

First it is simplistic to contrast the ‘historical with the legendary’. The portrait of Ashoka I have constructed in this book is based on Ashokan inscriptions and artefacts, yet it contains a heavy dose of interpretation, translation, imagination, narrative, perhaps bias… The ‘legendery’ is not simply false and to be dismissed; it is the reimagination of the past to serve present needs, something inherently human. These narratives were meaningful and important to the persons and communities that constructed them. Their purpose was not to do history in the modern sense of the term, but to do something much more significant to them in their own time.

….There are actually not two but several Ashokas, including modern ones”.

Following this argument, we Lankans who try to practice ‘Loving-Kindness’ must be thankful that Gananath has highlighted for us at least two Dutthagaminies, in his timely essay, Dutthagamini and the Buddhist Conscience, written in the wake of the carnage of the ‘July ‘83’ state sponsored pogrom against the Tamil people of Lanka. There is the familiar Dutthagamini, taught to us in school, as a Sinhala-Buddhist, Tamil-hating ethno-nationalist, constructed from the Mahavamsa narrative taken as incontrovertible historical fact. On the other hand, Gananath presents evidence, from the Dambulla temple paintings, for a humanist Dutthagamini, who like Ashoka himself, was contrite about the mass slaughter he conducted and his killing of Elara the Tamil king.

The film shows us how Gananath makes a radical scholarly move in the late stages of his life by researching the indigenous folk of Lanka, the Veddhas. He argues against the deep-seated idea, promulgated by the ethno-nationalist Sinhala-Buddhist ideologues, that there is an ancient historical enmity between the Sinhala and Tamil folk of Lanka going back to the days of the kings, prior to colonialism. Gananath analyses the myth of origin of the Sinhala folk as represented in temple murals that show Vijaya’s arrival in Lanka from India and his marriage with the indigenous woman Kuveni. The Veddhas are the descendants, he says, of Kuveni and her children by Vijaya and are the ‘other’ or outsider, so to speak, to the Sinhala.

Through his ethnographic work on the powerful Vadi procession (perahera) in Mahiyanganaya, Gananath is able to show the ritual means through which they are incorporated into the Sinhala community. The ethnographic film, demonstrating this robust festive ritual event of staging cultural difference and incorporation, supports Gananath’s argument that the Veddas have been the true ‘outsiders’ of the Buddhist polity (in dress, culinary habits, religion), and despite that, the Buddhist culture had ritual mechanisms of incorporation of the outsider, without resorting to slaughter, while also acknowledging and respecting the awesome power of the Veddas. This section should be shown to school kids, I think, because of its liveliness and pedagogic value. Gananath acknowledges the fine scholarship of Paul E. Peiris on the Veddas and shows the colonial hostility and violence towards these indigenous folk of Lanka. Gananath’s ‘Cook Book’, also relevant to Australia’s colonial history, would have provided a global perspective on colonisation of indigenous peoples and the violent means used in casting them as ‘uncivilised primitives’, which in turn would have prepared him well to write the book on, the Veddas, Creation of the Hunter, in 2022.

What to Do, Napuru Kaleta? (In Wicked Times)

It seems to me that young scholars and artists might be able to generate a new thought or two by reading Gananath’s essays and books in relation to Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Mediaeval Sinhalaese Art (Campden: Gloucestershire, 1908) and Olivelle’s book on Ashoka. In this way, the monodisciplinary compartmentalisation of knowledge, ideas, can be disturbed so as to gain aesthetic nourishment to create, with what’s left, after the ravages of Neoliberal cultural nationalism’s cognitive extraction of our brains. All three distinguished, visionary Lankan scholars were writing about times when material culture and the ‘Intangible Heritage’ (A UNESCO Platform for their preservation) of Lanka and India were/are being destroyed from within, extinguished.

Some ‘transversal’ or lateral ways of understanding and connecting material practices/stuff and immaterial ideas are called for now, I believe, and these three Lankan scholars have shown us many ways in which this can be done. Let me clinch my argument by citing the full title of Coomaraswamy’s indispensable book which took 60 years to be translated into Sinhala. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa (who also taught ‘mati-weda’) gave me this information for which I am most thankful. I read it in English as an undergraduate, quite by chance. Here’s the extended title:

“Being a Monograph on Mediaeval Sinhalese Arts and Crafts, Mainly as Surviving in the 18th Century with an Account of the Structure of Society and the Status of the Craftsman.”

Gananath might well have known through Ludowyk that the first edition of this book was hand printed in England by Coomaraswamy himself over a period of 15 months on the same printing press (which he purchased), as the one in which the first edition of the complete works of the Mediaeval English poet Chaucer was printed by William Morris, one of leaders of the ‘Arts and Craft Movement’. There is a wonderful story I heard from a native informant of California, of Gananath’s freshman lecture at the University of California in San Diego, on Pilgrimages. On hearing Gananath recite an entire section from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales ‘by heart,’ the students gave him a standing ovation!

Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies, (namely Social Ecology, Mental Ecology, Environmental Ecology), is another a book worth reading (now freely downloadable), alongside the others as he was a radical psychotherapist trained in psychoanalysis by Lacan, and a Left Activist in France who also collaborated with the philosopher Gilles Deleuze on Anti–Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1968), which was a best seller. He also worked at a humane, innovative mental health institution which was part of the radical anti-psychiatry movement of the 60s and was a wild thinker who reminds me of Gananath and also had the requisite discipline, like him, to write books that crossed generations. He died all too soon, but Gananath will turn 95 on the second of February 2025.

Finally, my gratitude to the producers of this film, the Kathika Collective whose independent spirit, deep research, dedication, and not least, the love of cinema has led to the production of this film over a long period of time, which included the hiatus of the COVID pandemic. While Dimuthu is credited as researcher, script writer and director and Chathura Madhusanka with editing and camera, a great many well wishes (acknowledged in the credits), contributed freely to this film which has not received any external funding. The spirit of education that drove this film is a truly beautiful tribute to Gananath and Ranjini Obeysekere, our indispensable mentors, both.

Yahonis Pattini Kapumahattya’s haunting voice emanating from a deep folk history (which Gananath much admired and we are privileged to hear), accompanies the long credit list.

The film is dedicated:

“To all rural folk who in their diverse ways enriched the peasant Buddhist tradition and found Buddha in that”. (Concluded)

Opinion

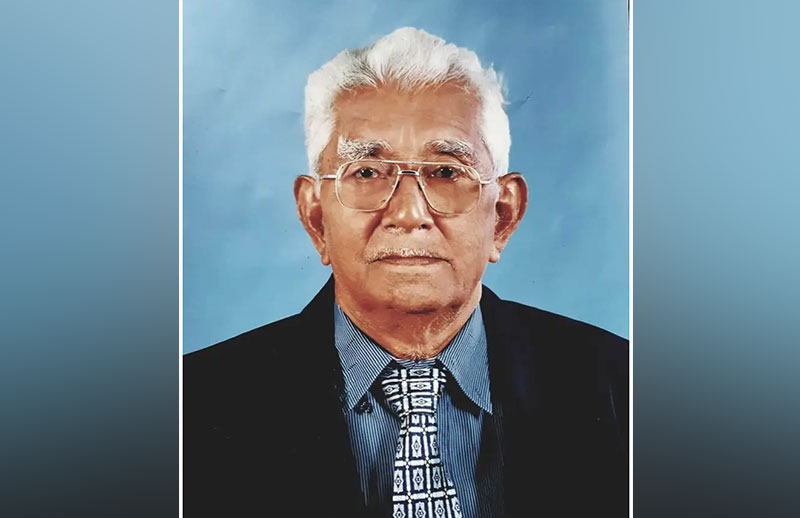

End of an Era: Passing away of Raja Uncle (Mr. Rajapaksha)

1935 – 2025

With heavy hearts, we share the passing of our dear neighbor, mentor, and cherished friend, Raja Uncle — known formally as Mr. Rajapaksha — who passed away peacefully on April 1, 2025, at the age of 89.

For over 50 he was a constant and beloved presence in our community — someone whose actions spoke louder than words, and whose kindness left a mark on every life he touched. Gentle in spirit, firm in values, and endlessly thoughtful, he helped shape the heart of Bogahawatta with his humility, quiet strength, and unwavering dedication.

He carried himself with grace and dignity — slim, well-groomed, and strikingly handsome, with a calm confidence that made people feel at ease. He never tried to be a person who gave orders — instead, he led through respect, active listening, and thoughtful action. His leadership was never loud — it was steady, consistent, and deeply human.

A founding member of the Bogahawatta Welfare Society, Raja Uncle gave more than 40 years of devoted service to the betterment of the Bogahawatta community. In the 1980s, as the area grew and safety became a concern, he established the neighborhood watch, restoring trust and unity in a time of change.

He organized road cleaning and repair efforts, worked alongside neighbors, and played a vital role in the construction of the Bogahawatta Welfare Society headquarters, which stands today as a symbol of unity and progress.

He also cared deeply for everyday needs. For nearly 20 years, before running water was available, the community well was a lifeline. When it fell into disrepair, Raja Uncle would quietly take the responsibility to clean and maintain it, asking for no recognition. I had the honor of helping him at times, and I saw the pride and purpose behind every quiet act.

When I served as president of the local youth society, he became my mentor. With his help, we organized a talent show, community art exhibition, built a mini library, and gave young people opportunities to lead. His daughter Tharanga, the society’s secretary, worked beside him — a reflection of the values he passed on.

He also shaped my personal journey. He introduced me to a temple, and gently guided me toward a spiritual life I still hold close today.

He was our protector. If a stranger walked down our lane, he would calmly and respectfully inquire about their purpose, ensuring the safety of every home and child. During a heated argument in my youth, he stood nearby for over an hour, silently watching until it ended, and then walked me home. He didn’t lecture. He didn’t judge. He simply cared.

Every April, without fail, he was the Master of Ceremonies at the Sinhala and Tamil New Year festival. His voice, his presence, and his joyful warmth brought the entire community together in celebration year after year.

In times of sorrow, he led with compassion. He would gather neighbors to visit grieving families, sometimes traveling great distances, and delivered eloquent eulogies that offered comfort and honored lives with dignity.

What truly set Raja Uncle apart was his love — especially the remarkable bond he shared with his wife. Their marriage was the most loving I have ever witnessed. They were the love of each other’s lives — gentle, respectful, and unwavering. He never raised his voice. They never let conflict come between them. Their partnership was built on trust, affection, and shared values.

In July 1980, as public servants, the two of them stood together in protest against unjust government layoffs. They both lost their jobs, but they stood by their beliefs. They started a business together, overcame hardship side by side, and were eventually reinstated. In time, Mrs. Rajapaksha rose to a top-level position in Sri Lanka’s Department of Immigration and Emigration — a testament to her brilliance and their shared resilience.

They raised their children in a home of dignity and purpose. In a country where less than five percent were admitted to university at the time, all three — Tharanga, Lahiru, and Lasitha — were accepted. A rare and proud achievement rooted in hard work and love.

His family grew across the world — Lasitha became a British citizen, and Lahiru a citizen of Australia. Raja Uncle visited them often, maintaining the same closeness and warmth across any distance.

And perhaps the most remarkable of all: he helped lead a place that was once a quiet, forested area in the 1970s into a thriving, respected neighborhood — one so valued that even a Defense Secretary of Sri Lanka chose to make it his home. This was not the work of ambition, but of vision and service — built slowly, over decades, through trust and integrity.

To me, as his next-door neighbor, he was one of the most steady and trusted influences in my life. He showed me that a meaningful life isn’t defined by what we achieve — but by how we treat others, what we give, and how we listen. I shaped my life after him.

Although I haven’t been as closely associated with him since leaving Sri Lanka in 2000 and becoming a citizen of the United States, his memory has remained with me every step of the way. These are just a few of the memories I carry — as much as I can recall. I still wish, from the bottom of my heart, that he could be my neighbor forever — to guide me, to listen, to share his quiet vision.

He touched so many lives, across generations. There are countless stories, small and great, that live on in the hearts of those who knew him. His presence will be remembered not only through words, but in the community he shaped, the values he carried, and the lives he quietly uplifted over these 50+ years.

May his soul rest in peace, and may we carry forward the spirit he lived by — humility, strength, compassion, and quiet dedication — just as Raja Uncle did, every single day of his extraordinary life.

Opinion

Some aspects of China’s development model

by Shiran Illanperuma

China’s rapid development over the last few decades has been the source of much debate among economists. Some claim China as the model par excellence of market liberalisation and the superiority of private sector driven growth. Others equally argue that China’s model is one of planning and state intervention.

On 28 March, I was invited by Nexus Research to deliver a presentation on China’s development model alongside former Ambassador to China Dr. Palitha Kohona. Unfortunately, the contents of this presentation have been misreported in an article in the Island published on 4 April (Dr Kohona: developing countries should covet China model). The article claimed that my presentation touched on “low-cost labour, foreign direct investments, and global trade agreements”. In fact, such simplistic tropes were precisely what I had intended to counter.

China’s development model challenges many of the axioms of neoclassical economics. If low-cost labour were the decisive factor for take-off, then investment should be pouring into much-cheaper labour markets in sub-Saharan Africa. On the contrary, rising wages in China have not led to the outflow of capital one would expect under such a model. This is because the advantage China offers is a healthy and skilled workforce (relative to price) and an infrastructural system that keeps non-wage operating costs (such as transport and energy) low. This, combined with a domestic value chain, is China’s main strength and why economic growth has been combined with rising wages and standards of living.

While foreign direct investment (FDI) has been a huge part of China’s success story, it is possible to overstate their importance. First, FDIs only really took off from the 1990s onwards, yet to begin there would be to ignore the decades of work done to develop the country’s agricultural self-sufficiency, basic industrial system, and institutional structure. Second, what has mattered for China is the quality of FDI, which is determined by government policy. By the standards of the OECD Foreign Direct Investment Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, China remains fairly selective on what FDI is allowed and encouraged. FDI is promoted not as an end in itself but as a means to acquire technology that should be transferred to national champions.

Role of Local Government

A significant portion of my presentation for Nexus Research was on the role of local governments economic policy – something that is often neglected (though there is a growing literature on the subject). China has a fairly decentralised system of governance, a product of its vast size and geography, as well as the institutional changes and experiments in direct democracy during the period of the Cultural Revolution.

Chinese economist Xiaohuan Lan, in his book How China Works (2024), has said that “In China, it is impossible to understand the economy without understanding the government.” While the central government in China formulates indicative plans and the overall goals and trajectory for development, implementation of these plans is delegated to local governments. Local governments have a broad remit to interpret these plans, experiment with implementation, and compete with each other for investment. This leads to a much more dynamic and decentralised development process that encourages grassroots participation.

A comparison between China and India on the share of public employment at different levels of government is very revealing. For China, over 60% of public employment is at the level of local government, with federal and state governments comprising less than 40% of employment. In contrast, less than 20% of Indian public employment is in local government. India, therefore, despite its much-touted linguistic federal system, is far more centralised than China. The weakness of Indian local governments remains a significant barrier for its development.

The Role of SOEs

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are the elephant in the room when it comes to China’s development model. Chinese political scientist Prof. Zheng Yongnian said in 2011 that “the state sector is in fact important for China’s macroeconomic stability.” This is a radically different approach from neoclassical economics, which views macroeconomic policy purely through the lens of fiscal and monetary policy.

Broadly speaking, SOEs in China perform four ‘macroeconomic’ functions. First, they conduct the low-cost production of upstream inputs such as metals, chemicals, and rare earth minerals. Second, they manage essential commodity reserves and intervene in commodity markets to stabilise prices. Third, they engage in countercyclical spending on public works during economic downturns. Fourth, they are deployed to respond during emergencies and external shocks such as the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and the COVID-19 pandemic. The through line in these functions is to keep costs low and smoothen out business and commodity cycles. This is why China has not yet faced a recession comparable to many capitalist economies.

As a consequence of this model, SOEs remain a significantly large part of the Chinese economy in quantitative terms. According to data compiled by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, SOEs accounted for around 75% of the aggregate revenue of Chinese firms in the Fortune 500. While it is true these firms are often not as profitable as the private sector, this is by design, as they pass on low prices to domestic manufacturers.

China has entities such as the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) which facilitate the centralised governance and oversight of SOEs. This model is crucially different from the Temasek model often discussed in Sri Lanka. Under Temasek, SOEs are almost entirely market-oriented and depoliticised. This is not the case in China, where SOEs continue to play crucial social and political functions.

The Role of Competition

What confuses most observers of China is the fact that it very obviously has a fiercely competitive and dynamic private sector. How then to reconcile the preceding elaboration of the role of local government and SOEs with a competitive private sector? Local governments and SOEs provide the basic institutional framework and economic building blocks for the private sector to play its role in capital accumulation and innovation.

The competitive cycle in China could be broadly divided into four phases. In the first phase, incentives created by the central and local governments lead to a flood of investment in desired sectors and sub-sectors, resulting in the establishment of new firms and production capacity. In phase two, these incentives are eased, leading to fierce competition and survival of only the fittest firms. In phase three, once the market has reached a stage resembling monopoly, one of three tactics may be used: 1. Firms are forced to compete internationally and export; 2. monopoly firms are broken up by the state; or 3. monopoly firms are nationalised or brought under stronger state supervision. The system is designed to resist the market’s natural tendency towards monopolisation.

Political Leadership

The Chinese state has an exceptional ability to maintain what political sociologist Peter B. Evans calls ‘embedded autonomy’. It is close enough to the private sector to understand economic conditions and formulate policy but politically independent enough from capital to resist capture by private interests. This is a key difference between China’s development model and the developmentalism of East Asian states such as Japan and South Korea, where large private firms (zaibatsu in the former, chaebols in the latter) dominate political life.

China’s development model cannot be understood in isolation of its leadership system. The Communist Party of China, which has around 100 million members (almost five times the population of Sri Lanka!), has been key to the process of China’s development. The party remains committed to developing Marxist-Leninist philosophy and applying it to the country’s concrete conditions. It retains deep roots in all levels of Chinese society, engaging in consultation during the policymaking process.

To what extent China’s model can be replicated by other countries is an open question. While the CPC has often invited academics and political parties to study its system, this does not equate to the party attempting to export said system. There is no real ‘Beijing consensus’ that is equivalent to the ‘Washington consensus’. On the contrary, President Xi Jinping, in 2023, cautioned that modernisation “cannot be realised by a cookie-cutter approach”.

“For any country to achieve modernisation, it needs not only to follow the general laws governing the process but, more importantly, consider its own national conditions and unique features.”

(Shiran Illanperuma is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a co-editor of Wenhua Zongheng: A Journal of Contemporary Chinese Thought. He is also a co-convenor of the Asia Progress Forum which can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com)

Opinion

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part IV

Sri Lankan Foreign Policy since the End of the Cold War

By the end of the Cold War, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy priorities were predominantly shaped by its armed conflict with the LTTE, despite pivotal shifts in its regional and global geopolitical spaces. The significance of the country’s foreign relations was largely viewed through the lens of its strategic needs in the ongoing civil war, often overshadowing other broader regional and global developments.

The Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord of 1987 and the subsequent establishment of the Provincial Council system under the 13th Amendment to the Constitution failed to bring lasting peace and merely perpetuated the vicious cycle of violence. Meanwhile, the uprising (1987-1989) led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) and its ruthless suppression deepened the political and social turmoil and tarnished the country’s democratic credentials, further constraining the government’s ability to focus and react to broad external strategic developments. As a result, the critical shifts occurring in South Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the global strategic environment after the Cold War were more or less overlooked in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy decisions.

Following the decisive military defeat of the LTTE in 2009, Sri Lanka underwent a significant shift in its politico-strategic needs, marking the beginning of a new phase in the country’s foreign policy. With the conclusion of the protracted civil war, a different set of issues came to the forefront and decided Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and geopolitical priorities. Accordingly, the evolution of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy in the post-Cold War era can be divided in two distinct phases, with the end of the war in 2009 acting as a pivotal turning point.

Enduring Crises and Foreign Policy

under President Premadasa

When Ranasinghe Premadasa assumed the presidency after a violence-ridden election, Sri Lanka was mired in multi-faceted crises. The Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), initially deployed to supervise the Peace Accord, quickly found it embroiled in violent conflict with the LTTE in the North. Maneuvering the IPKF’s withdrawal without alienating India became a delicate and daunting challenge. Meanwhile, the brutal suppression of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) insurgency in the South only deepened the country’s instability and culpability, further intensifying international backlash over human rights violations.

Despite facing significant challenges, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy lacked coherence and strategic direction. The government’s foreign policy responses were often reactive, addressing events in isolation rather than within a broader strategic framework. Decision-making appeared to be driven more by immediate political considerations than by long-term objectives. As a result, Sri Lanka became entrapped in a foreign policy dilemma, struggling to manage multiple crises across various fronts simultaneously.

One of President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s key achievements was persuading/pressuring India to withdraw the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka in 1990. However, it also strained Indo-Sri Lanka relations in the short term. One of the key achievements of President Ranasinghe Premadasa was persuading India to withdraw the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka. However, this success came at the cost-damaging Indo-Sri Lanka relations.

During a public meeting on June 1, 1989, President Premadasa demanded the complete withdrawal of the IPKF from Sri Lanka by July 29, 1989, giving India just two months’ notice. India was taken aback by the manner in which this demand was made and made it clear that Sri Lanka could not impose a unilateral deadline. India was only prepared for a phased withdrawal and had limited options. In response, India made a misguided decision to train a Tamil National Army.

In an effort to pressure India into withdrawing the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka, President Premadasa sought to leverage the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). In July 1989, Sri Lanka boycotted the SAARC Ministerial-level meeting in Islamabad, Pakistan. Furthermore, Sri Lanka made it clear that it would not host the SAARC Summit scheduled later that year in Colombo. The Sri Lanka informed SAARC countries that the Summit could not precede in Colombo as long as the IPKF remained stationed in the country against its will (RavinathaAryasinha, 1997: 54)

After V.P. Singh of Janata Dal became Prime Minister of India in December 1989, the withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka was expedited. In contrast to Rajiv Gandhi’s position, I.K.Gujral, the External Affairs Minister in the Janata Dal government, stated that “Tamil security is an internal matter of Sri Lanka.” He expressed hope that the Sri Lankan government had learned from the lessons of history and would no longer deny the country’s ethnic minorities their due rights (Sunday Times, 29 April 1990).

However, the rescheduled Summit for Colombo in 1990 was ultimately not held there. The Maldives insisted on hosting the summit in Malé, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of it becoming a Republic. The failure of the planned 1990 summit in Colombo also reflects the complex regional dynamics at the time.

After the withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in 1990, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) swiftly reemerged as a formidable military and political force in the North and East of Sri Lanka, setting the stage for the onset of Eelam War II in June 1990. In the 1990s, parallel to the expansion of Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora, the LTTE’s international influence grew significantly.

Its front organisations in Western countries became increasingly active, openly fundraising, pressuring host governments on behalf of the LTTE, and even facilitating the transportation of arms and supplies to the conflict zones in Sri Lanka. This growing international network of support posed a substantial challenge to the Sri Lankan government. Moreover, the LTTE frequently framed its actions as a response to alleged human rights violations by the Sri Lankan government, using this narrative to justify its activities and gain international sympathy and support. The complexities of this issue—encompassing both military confrontations and political maneuvering—posed a formidable challenge that required a comprehensive strategy and sharp diplomatic acumen.

The Premadasa administration failed to fully recognise the growing significance of the international public sphere and the increasing prominence of international human rights frameworks. These were often dismissed as instruments of the LTTE’s propaganda. The Sri Lankan government held a largely negative view of Western countries that raised human rights concerns, perceiving these countries as supportive of the LTTE. This perception, coupled with a failure to distinguish between the LTTE and the broader ethnic conflict, impeded the government’s ability to formulate an effective strategy in response to international criticism.

Despite his unconventional approach, President Premadasa recognised that the Foreign Ministry was in disarray, lacking direction amidst the decisive challenges facing the country. In response, he established a Foreign Affairs Study Group, chaired by Dr. Gamani Corea, to address the situation (Dayan Jayatilleka, 2017). The group completed its report on restructuring Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and diplomatic missions, but before it could be presented, President Premadasa was tragically assassinated. Following his death, President Wijetunga, the caretaker president, assumed office but hesitated to take any new initiatives on the matter.

Change Vision and Restructuring under President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga

The efforts to instill a new policy vision and reshape the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) began after the People’s Alliance (PA) assumed power in 1995 under the leadership of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. By the time Kumaratunga assumed the presidency, the MFA was in disarray—lacking direction and burdened by excessive politicisation. To address this, President Kumaratunga appointed Lakshman Kadirgamar as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Drawing on his extensive experience as an international civil servant, Kadirgamar implemented reforms to streamline recruitment, promotions, and diplomatic postings, restoring some order to the MFA. At the same time, the government sought to bolster Sri Lanka’s democratic image on the international stage.

Strengthening the country’s credentials as a functional democracy was viewed as essential for garnering global support in addressing the LTTE military challenge. In this context, internal policy reforms were expected to provide strong backing to a foreign policy with a clear vision and direction.

The PA government marked a significant departure from the antagonistic stance of its predecessors towards international human rights bodies. Recognising the growing influence of the global public sphere on national policies, the PA government made a deliberate effort to engage with key international human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations. These engagements included open dialogues aimed at addressing concerns about Sri Lanka’s human rights situation.

The PA government’s commitment to international human rights standards and norms was demonstrated by its ratification of several major international human rights conventions. Additionally, the PA Government worked to strengthen domestic human rights institutions, particularly the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL), further solidifying its dedication to human rights both within Sri Lanka and on the international stage. These efforts were seen as essential for two reasons: promoting domestic reconciliation and enhancing Sri Lanka’s international credibility.

In light of the geopolitical implications of India’s strategic rise and changes in the South Asian geopolitical landscape, developing strong ties with India remained a key achievement of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy under the People’s Alliance (PA) government. After decades of mutual suspicion,

accusations, and tensions, both countries recognised the importance of normalising their relations. President Chandrika Bandaranaike’s new vision and foreign policy approach provided a significant opportunity for a fresh start towards rapprochement. The Indian government’s diplomatic shift, marked by the Gujral Doctrine introduced by External Affairs Minister I. K. Gujral in 1996, further paved the way for improved bi-lateral relations. Indo-Sri Lanka relations had not been as cordial for decades as they were under President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. A key testament to the South Asian policy of the Kumaratunga administration was the 10th SAARC Summit held in Sri Lanka in 1998. During this summit, informal discussions between India and Pakistan, initiated through the personal efforts of President Kumaratunga, marked a critical development in the regional strategic context.

Under President Premadasa, Sri Lanka’s relations with Western powers, particularly Britain and the United States, began to deteriorate rapidly. For a small country like Sri Lanka, which was grappling with a significant internal armed conflict with international Diaspora linkages, navigating the post-Cold War global strategic landscape became a critical challenge. Nearly two-thirds of Sri Lanka’s export market was tied to the West—primarily Britain, the United States, and the European Union. At the same time, the LTTE’s international headquarters operated from Western capitals. Given this, Sri Lanka paid a steep price for its adversarial stance toward these Western powers. In contrast, one of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s notable achievements was her efforts to foster better relations with the West. By implementing internal democratic reforms and adopting the PA’s approach to the ethnic crisis, she created a more favourable environment for diplomatic engagement. This foreign policy shift paid off: In 1996, the United States resumed arms sales to Sri Lanka, and the US “Green Beret” corps began offering advanced training to the Sri Lankan security forces. This military support included specialized training missions by the US Navy SEALs, the US Air Force Special Operations Squadron, and the US Army’s Psychological Operations Group. The proscription of LTTE as a terrorist organization by the United States in October 1997, followed by similar designations from the United Kingdom in 2000 and Australia in 2001, dealt a severe blow to the LTTE international operations.

The dynamics of the crisis, however, posed significant obstacles to the continued implementation of this policy. Negotiations with the LTTE, which began in October 1994, collapsed on April 17, 1995, when the LTTE withdrew from both the talks and the ceasefire after four rounds of discussions. The hope of achieving a negotiated settlement with the LTTE was dashed within six months. The conflict with the LTTE once again became the central focus of foreign policy, but this time, the government’s

approach shifted from defensive to more assertive.

With the onset of Eelam War III, the government launched the Reviresa operation in November–December 1995 and regained control of Jaffna from the LTTE. In September 1996, the government conducted the Sath Jaya operation, which led to the recapture of Kilinochchi. However, the situation began to change in 1998. The government’s attempt to establish a land route to Jaffna failed, resulting in heavy human and material losses. By late 1998, military camps in Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, and Elephant Pass fell to the LTTE. Between 1999 and 2000, the Sri Lankan government forces suffered continuous setbacks on the military front.

Similarly, the proposal for the devolution of power, which had been incorporated into a draft of the new constitution, became entangled in political debates with the United National Party (UNP). The country had shown readiness to accept devolution through widespread public awareness campaigns, such as the Sudu Nelum movement. However, when the proposal was only presented to Parliament in August 2000, it was rejected by the UNP. As a result, the People’s Alliance (PA) government was unable to fulfill one of its key political promises to both the Tamil people and the international

community.

In 1999, another attempt was made to resume talks with the LTTE, this time with the prospect of third-party facilitation. President Kumaratunga explored the possibility of securing international involvement, with potential facilitators including France, a joint Commonwealth team, and the Vatican. By March 2000, the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE agreed on Norway as the mediator. With Norwegian facilitation, a Ceasefire Agreement was drafted between the Sri Lankan Government and the LTTE, scheduled to be signed on April 11, 2001. However, two days before the signing, the LTTE

unexpectedly declared that they would not proceed with the agreement, without providing any explanation for their decision.

(To be continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSuspect injured in police shooting hospitalised

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRobbers and Wreckers

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSanjiv Hulugalle appointed CEO and General Manager of Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams Sri Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBhathiya Bulumulla – The Man I Knew

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoNational Anti-Corruption Action Plan launched with focus on economic recovery

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoLiberation Day tariffs chaos could cause permanent damage to US economy, amid global tensions

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoMembers’ Night of the Sri Lanka – Russia Business Council of The Ceylon Chamber of Commerce

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMinds and Memories picturing 65 years of Sri Lankan Politics and Society