Features

When two Richards fought for Kelaniya in the 1956 elction

By Avishka Mario Senewiratne

Eight years after independence, Ceylon – relatively new to democracy and independent rule, though looking good on the global canvas – was on the verge of the humiliating defeat of its ruling government led by the United National Party (UNP). The vast masses of Ceylon had been disillusioned by the pro-elite UNP politics and were persuaded to vote for the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP) led by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, the leader of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). Though toxic for the future, the majority were inclined to see the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act, canvassed by the MEP in a favourable light.

Since the early 1940s, Junius Richard Jayewardene was known to be a highly accomplished and methodical politician. He served as the Minister of Finance in the Cabinet of D. S. Senanayake (1947-1952) and Dudley Senanayake (1952-53), and as Minister of Agriculture and Land (1953-56) in Sir John Kotelawala’s regime. Undoubtedly, he was second in line to be the leader of the UNP as well as to be Ceylon’s Prime Minister. However, in 1956, despite his excellent track record in politics, there was little he could do to retain his parliamentary seat in Kelaniya when Richard Gotabaya Senanayake challenged him.

Uncle and Nephews of the UNP

The story began with one man who did not live beyond 1901. This was Mudaliyar D. C. G. Attygalle, a father of four; three daughters and a son. The three daughters married John Kotelawala Sr. (father of Sir John), F. R. Senanayake (father of R. G. and brother of D. S.) and Col. T. G. Jayewardene (uncle of J. R.). When Ceylon received independence in 1948, the sons and nephews of all these esteemed gentlemen were prominent members of the United National Party, and in high office or eagerly waiting their entry.

The UNP was chartered in 1946 by D. S. Senanayake, who would be PM a year later. His successors were to be his son and nephew. Some high officials of the party were related to him, as well. For these obvious reasons, critics of the UNP ridiculed the party acronym as “Uncle-Nephew Party” and also pilloried it as “Unge Neyange Paksaya” – ‘their relations’ party’ (Weerawardana, p. 121).

The subjects of this essay, J. R. Jayewardene and R. G. Senanayake were thus related to each other and had a friendship since their childhood. When R. G. Senanayake entered politics in 1944, his friend J. R. was a well-established politician. Despite being a victim of polio and unable to be as active as he would wish, RG strived to serve his people with great charm, enthusiasm and sincerity. According to Prof. K. M. de Silva, RG hardly made an impact in the legislature, and if not for his being the son of F. R. Senanayake, many may have questioned his appointment as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs in 1947 (de Silva and Wriggins, p. 266). This Ministry was under his uncle DS, the Prime Minister.

The two Richards in San Francisco

In September 1951, all was set for the Japanese Peace Treaty Conference in San Francisco. However, Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake declined to travel for the event despite being Minister of External Affairs as his knowledge of foreign affairs was limited to the sub-continent. He suggested that JR should represent Ceylon. At JR’s request, DS appointed RG to accompany him, along with a private secretary, R. Bodinagoda later Chairman of Lake House. The only other person on the entourage was JR’s wife, Elena Jayawardene.

Not only was this delegation small but it also was poorly equipped, given its lack of informed aides and stenographers unlike delegations of other countries at the San Francisco Conference. Nevertheless, for JR this was a great opportunity and the beginning of a long association with Japan. His 15-minute speech created a major impact on the conference stressing Japan’s right to be a free state. JR became an instant global celebrity and PM Yoshida of Japan shook his hand with tears of joy in his eyes.

This was an unexpected triumph for Ceylon and its future leader, JR. Young R. G. Senanayake received a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to watch how his senior colleague won over leaders of the world in San Francisco. JR and RG along with Sir Claude Corea, the Ambassador of Ceylon to the USA, travelled to various parts of the US visiting the Ceylonese diaspora in that country.

Two Richards, two foes

With the passing of time, RG developed ambitions for high office. However, the presence of his cousins in senior positions deprived him of the opportunity to quickly achieve his political goals. Though concealed by his charm and winning ways, there was little RG could do to prevent displayng his true goals and envy of his cousins. He believed that Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake had taken over his own father’s destiny (F. R. Senanayake died prematurely in 1926) of becoming Ceylon’s first prime minister, and that his cousin Dudley was in the position which would otherwise have been his (see de Silva and Wriggins, pp. 265-266).

Soon, however, a major rift between JR and RG began to appear and their lifelong friendship was over by early 1952. Apart from his political ambitions, the tension between JR and RG was aggravated by a family dispute over RG’s association with his future wife, Erin. The bitterness in their personal lives spilled over into the political field and soon they were enemies.

Yankee Dicky Vs China Dicky

Despite the obvious signs of the careerist in RG, when Dudley was made Premier upon the untimely death of his father, he appointed his cousin RG as Minister of Trade and Commerce, while Jayewardene was re-appointed as Minister of Finance. In this capacity, RG built a formidable name for himself when he convinced the Government of Ceylon to sign the Rubber-Rice Pact with China in 1952. This was the crowning achievement of RG’s political career and it won him the name “China Dicky”.

Realising the demand for rubber in China and his country’s need for rice at the cheapest possible price, RG urged his government to forget their political differences with China and reach a Rubber – Rice Agreement. Though PM Dudley and his Cabinet strongly backed RG’s strategy, the Minister of Finance, now labelled “Yankee Dicky”, was not in favour of the Pact and vehemently opposed it. This was well reported in the Times of Ceylon. Dudley Senanayake believed that the Pact would solve Ceylon’s food shortage and boost the economy to a great extent as well as help find opportunities to seek new markets (see Amarasingam, where ??? p. 3).

JR was critical of the Pact for two reasons. One was that the USA would be (they later were) concerned and critical of Ceylon’s association with China. At a time when Ceylon was seeking entry to the UN, how would other nations perceive such a stance? The other was how China might influence the economy of Ceylon as they were to have a monopoly on the purchase of Ceylon’s rubber.

Nevertheless, the Pact was a great success and, after being renewed every five years, remained in effect till 1982. The supply of rice to Ceylon by China at prices below the world market resulted in a net benefit of about Rs. 92 million in 1953 alone. RG’s popularity was secured in comparison to that of the Minister of Finance. Consequently, the bitterness and envy between the two Richards further deepened.

RG leaves the Cabinet

A year later in 1953, with the infamous Hartal, the sensitive Dudley Senanayake resigned from his office as Prime Minister and thus Sir John Kotelawala – who had been expected to succeed DS in 1952 – was made Ceylon’s third PM. While R. G. Senanayake was re-appointed as Minister of Trade, J. R. Jayewardene was given a new portfolio; that of Minister of Agriculture and Land. JR was Sir John’s most trusted lieutenant and the new PM held him in high esteem and confidence.

On the other hand, Sir John’s relationship with his cousin RG deteriorated by 1954 when the latter opposed the Premier’s contemplated visit to the USA. RG had feared that Sir John would reach a deal with the Americans and break away from Ceylon’s policy of remaining neutral in foreign affairs. Furthermore, RG was critical of the appointment of Sir Oliver Goonetilleke as Governor-General, as well as Sir John’s attempts to seek a solution to the problems of the Indians in Ceylon’s polity.

Partly for these reasons, RG resigned from the Cabinet. However, it was well known that the real reason for his resignation was his opposition to JR whom he severely disliked. Deeply embarrassed by RG’s actions, Sir John later wrote the following in his memoirs: “The good God gave me friends, but the devil gave me my relations. It is an irony of fate that at critical stages of my public career some of my relations, instead of rallying around me, have caused me the most embarrassment and trouble.” (An Asian Prime Minister’s Story, p. 130)

An early election in 1956

1956 was a key year in the annals of Ceylon’s history as the majority of Buddhists were preparing to celebrate the 2500th Buddha Jayanthi. The Buddhist clergy had asked the government to keep the year free of political agitation. On the other hand, the movement to do away with English as the State language and implement Sinhala Only was making strong headway. The leader of the SLFP, S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was clamouring for it along with his large coalition of parties (the MEP).

The feudal-style UNP regime had lost much of its credibility with the public as the government failed to cater to their demands despite being a stable regime with much promise. Influenced by the advice of Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, Sir John was keen to hold the elections as early as April 1956. Being neutral on the language policy, on the insistence of many of his aides including JR, Sir John decided to give into Sinhala Only in early 1956.

By doing this last-minute volte-face, Sir John expected the UNP to score a comfortable win. However, he had gravely misread the trends of the day. The majority of Sinhalese had reposed much faith in the MEP while most of the Tamils were angered by Sir John’s last-minute policy shift on the language issue and refused to join forces with him at the election.

JR realised that his party was about to face an inevitable defeat. Furthermore, Sir John Kotelawala’s comments in the press on various social issues made him and his regime even more unpopular. It was in such a milieu that Parliament was dissolved in February 1956 although it could go on until January 1958. Accordingly, nominations were to be handed in by March 8 and the election was to be held on three days – April 5, 7 and 10.

The Kelaniya Electorate

J. R. Jayewardene first entered the State Council through a by-election held in the Kelaniya constituency in 1943. The previous holder of that seat was the most revered Sir Don Baron Jayatilaka who retired from politics and asked JR to succeed him. JR, however, had an opponent in the person of E. W. Perera, the famous freedom fighter. However, the poll favoured of JR as he amassed 21,765 votes against Perera’s 11,570 (Ceylon Daily News, 19.11.1943). Winning this historic election by over 10,000 votes was a great boon in the political life of JR. Through his grandmother (Helena Wijewardene’s) benevolent services to the famous temple of Kelaniya, this constituency was by all means related to JR. Kelaniya was a rural but growing electorate and consisted predominantly of Sinhala Buddhists.

In the subsequent election of 1947, JR once again ran at Kelaniya, under the banner of the newly formed UNP. This time he had a comfortable victory against Bodhipala Waidyasekera of the LSSP by over 7,000 votes (The Parliament of Ceylon 1947, p. 31). At the 1952 General Election, JR’s opponents were his aunt Wimala Wijewardene contesting from the SLFP and Vivienne Goonawardene of the LSSP. Based on this election result, JR reckoned that Kelaniya was not a safe seat for him any more as his majority against these two female candidates was less than 2,000. This was not a good record for JR as 1952 was a year the UNP was at its zenith. Therefore, he calculated that contesting again in Kelaniya was a risk, quite apart from the other troubles the UNP faced in 1956.

RG declares war on JR

R. G. Senanayake who was a Parliamentarian since 1947, had run at Dambadeniya successfully. He won both the 1947 and 1952 elections under the UNP banner with overwhelming majorities. He was expected to contest in the same seat again as he had won great respect and acceptance in this electorate. RG, unlike JR, was more of a people’s man, who rallied around the village folk and listened to their grievances. Wimala Wijewardene, a formidable opponent in the last election, had changed her seat to Mirigama and was expecting a comfortable win. However, until late 1955 there was no idea of whom to nominate for Kelaniya under the SLFP banner or that of any other party.

It was then that R. G. Senanayake declared that he would contest the Kelaniya electorate as an Independent candidate. He would also contest Dambadeniya as an Independent. This came as a great surprise to both JR and the MEP. Everyone knew that this move was to settle a personal vendetta against JR, and the MEP was initially reluctant to support RG, knowing his intentions and temperament. Senior journalist K. K. S. Perera once related to the writer that RG had at once said that he was coming to Kelaniya to remove a bad tooth from the next parliament!

It was clear that there was no other opponent in the calibre of RG who would defeat the all-powerful JR, the second in command in the UNP. For this reason, the MEP backed RG in Kelaniya. They would have good reason to remove JR from Parliament for they knew what a capable, methodical and shrewd politician he was. RG’s popularity under his father’s legacy, as well as the success he gained through the Rubber-Rice Pact, were well noted by the common men and women throughout the country. Another opponent JR had to face in Kelaniya was Ven. Mapitigama Buddharakkita Thera, who was not only the head of the Kelani Temple but also a leader of the Eksath Bikku Peramuna. He too supported RG to force JR’s exit from Kelaniya.

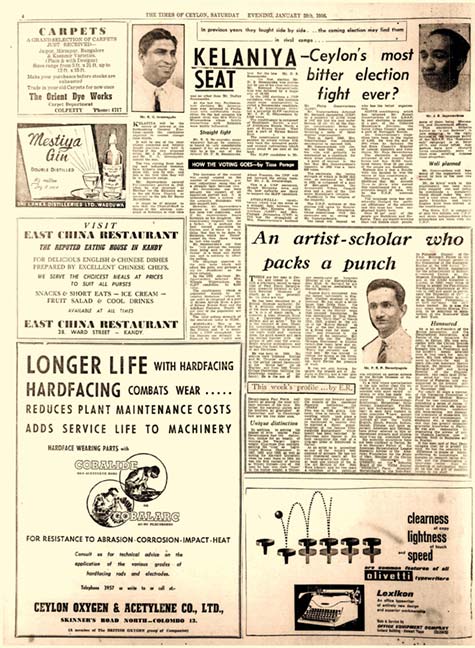

Times of Ceylon, January 28, 1956

JR’s unenthusiastic campaign and fate

After parliament was dissolved, JR holidayed for three days in Wilpattu and returned to Colombo with a much-relaxed mind but well aware of the apprehensions of the UNP. He had few doubts that he would lose his seat. However, he realised he did not have the time to campaign for the UNP in other parts of the country, even though his party needed his support now more than ever. Within a week or two into the campaign, JR fathomed that the UNP and his seat were doomed. Sir John’s blunders and controversial remarks made him unwittingly the MEP’s best campaigner (see de Silva and Wriggins, pp. 307-308). Visiting his own constituency, JR realised that his support had eroded.

He did attract crowds at his meetings in Kelaniya, but nothing similar to RG’s. Soon there were many jeers at these meetings, and stones were being thrown at JR’s car. What was more disappointing to him was to see Mrs. Robert Senanayake, Dudley’s sister-in-law (who was RG’s sister) campaigning against JR. This gave the notion that the Senanayakes were disillusioned with the UNP (see Dissanayaka, p. 40). Though Sir John visited Kelaniya on February 28, few were convinced that JR was winning. Day by day, attendance at JR’s meetings seemed to be diminishing in number.

The election was held on three separate days. The UNP selected those electorates where they were strongest to be held on the first two days. If they had done well on those two dates, it was possible that this would help change the electoral mood in constituenceis they were weak in. JR’s election was scheduled for the third day. However, the rout was clear when the UNP won only eight seats on the first day. The next two days brought the UNP no wins. The MEP, at this election, secured 51 seats with 40.7% of the vote.

The LSSP and the Federal Party won 14 and 10 seats each with vote percentages of 10.2% and 5.4%, respectively. The UNP, though holding 27.3% of the total vote, won just eight seats. Almost all its powerful Ministers, including JR, were defeated. Sir John comfortably won Dodangaslanda and M.D. Banda were among the eight UNPers to win their seats. Eight Independents and three members of the Communist Party were also elected. It was the worst defeat the UNP faced in the 20th century.

The results in Kelaniya were equally humiliating. As expected, RG topped Kelaniya with 37,023 votes (76%) whereas JR received only 14,187 (24%) votes (The Parliament of 1956, p. 21). JR was badly defeated and RG had accomplished his goal also winning Dambadeniya as an Independent with 94% of the votes against the hapless UNP candidate. This was the first time a single MP was represented two seats in Parliament. JR, knowing his fate, arrived at the Colombo Kachcheri where the votes were counted leaving the place after the results were declared amidst insults and jeers.

His car was hit with stones and rotten fruits as it left the premises. Escorted by the police, JR arrived at Braemar, his home in Ward Place. His driver was in tears and so was his younger brother, H. W. Jayewardene. However, JR remained calm and collected retaining his normal composure despite the humiliating defeat. He retired to his room in silence. A few days later, the man was seen back to normal with his spirits up, interacting with his family and, of course, planning his next election!

Aftermath

JR spoke very little of this episode, but nearly 40 years later in the preface to his memoir, Men and Memories, referred to the 1956 election as an “Electoral Holocaust”. He went on to say, “I had done much for the electorate but was defeated by an intruder in April 1956” (p. ix). With the defeat, one depressing outcome that emerged was that many of his close friends and relatives stayed away from him.

However, with much free time at his disposal, he went into serious reading, especially the six volumes of Winston Churchill’s History of the Second World War. It was through this book that he derived the motto, “In Defeat, Defiance”. JR used his defeat to focus on himself and opted to partner his old friend Dudley Senanayake to rebuild the UNP. Fortunes were such that the defiant JR would go on to become Sri Lanka’s first Executive President in 1978.

RG, on the other hand, was reappointed to the portfolio which he had previously relinquished. He worked closely with the new PM, S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. Though being asked to resign from one of his two parliamentary seats by the new PM, and also by the press, RG refused to do so (Manor, p. 264). It was once said that during parliamentary votes RG used to raise both hands as he represented both Kelaniya and Dambadeniya!

However, after Bandaranaike’s untimely assassination, RG never came to prominence as a Cabinet Minister in any of the future regimes of 1960 or 1965. Despite being ill, he once again contested in two electorates in 1970 (Dambadeniya and Trincomalee) losing both badly. He passed away prematurely aged 59 in December 1970. He was widely respected for his integrity and sincere care for the common people he represented.

“Defeat is never fatal. Victory is never final. It’s courage that counts.” – Sir Winston Churchill

References

Amarasingam, S. P., (1953), Rice and Rubber: The Story of China-Ceylon Trade, Ceylon Economic Research Association

De Silva, K. M. and Wriggins, H., (1988), J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka, Volume 1, Anthony Blonde/Quartet

Dissanayake, T. D. S. A., (1975), Dudley Senanayake of Sri Lanka, Swasthika

Fernando, J. L., (1963), Three Prime Ministers of Ceylon: An Inside Story, M. D. Gunasena

Jayewardene, J. R., (1992), Men and Memories: Autobiographical Recollections and Reflections, Vikas

Kotelawala, Sir J., (1956), An Asian Prime Minister’s Story, George Harrop & Co.

Manor, J., (1989), The Expedient Utopian: Bandaranaike and Ceylon, Cambridge

The Parliament of 1947,

The Ceylon Daily News

The Parliament of 1956,

The Ceylon Daily News

Times of Ceylon,

January 28, 1956

Weerawardana, I. D. S., (1960), Ceylon General Election

Features

Ethnic-related problems need solutions now

In the space of 15 months, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has visited the North of the country more than any other president or prime minister. These were not flying visits either. The president most recent visit to Jaffna last week was on the occasion of Thai Pongal to celebrate the harvest and the dawning of a new season. During the two days he spent in Jaffna, the president launched the national housing project, announced plans to renovate Palaly Airport, to expedite operations at the Kankesanthurai Port, and pledged once again that racism would have no place in the country.

There is no doubt that the president’s consistent presence in the north has had a reassuring effect. His public rejection of racism and his willingness to engage openly with ethnic and religious minorities have helped secure his acceptance as a national leader rather than a communal one. In the fifteen months since he won the presidential election, there have been no inter community clashes of any significance. In a country with a long history of communal tension, this relative calm is not accidental. It reflects a conscious political choice to lower the racial temperature rather than inflame it.

But preventing new problems is only part of the task of governing. While the government under President Dissanayake has taken responsibility for ensuring that anti-minority actions are not permitted on its watch, it has yet to take comparable responsibility for resolving long standing ethnic and political problems inherited from previous governments. These problems may appear manageable because they have existed for years, even decades. Yet their persistence does not make them innocuous. Beneath the surface, they continue to weaken trust in the state and erode confidence in its ability to deliver justice.

Core Principle

A core principle of governance is responsibility for outcomes, not just intentions. Governments do not begin with a clean slate. Governments do not get to choose only the problems they like. They inherit the state in full, with all its unresolved disputes, injustices and problemmatic legacies. To argue that these are someone else’s past mistakes is politically convenient but institutionally dangerous. Unresolved problems have a habit of resurfacing at the most inconvenient moments, often when a government is trying to push through reforms or stabilise the economy.

This reality was underlined in Geneva last week when concerns were raised once again about allegations of sexual abuse that occurred during the war, affecting both men and women who were taken into government custody. Any sense that this issue had faded from international attention was dispelled by the release of a report by the Office of the Human Rights High Commissioner titled “Sri Lanka: Report on conflict related sexual violence”, dated 13.01.26. Such reports do not emerge in a vacuum. They are shaped by the absence of credible domestic processes that investigate allegations, establish accountability and offer redress. They also shape international perceptions, influence diplomatic relationships and affect access to cooperation and support.

Other unresolved problems from the past continue to fester. These include the continued detention of Tamil prisoners under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, in some cases for many years without conclusion, the failure to return civilian owned land taken over by the military during the war, and the fate of thousands of missing persons whose families still seek answers. These are not marginal issues even when they are not at the centre stage. They affect real lives and entire communities. Their cumulative effect is corrosive, undermining efforts to restore normalcy and rebuild confidence in public institutions.

Equal Rights

Another area where delay will prove costly is the resettlement of Malaiyaha Tamil communities affected by the recent cyclone in the central hills, which was the worst affected region in the country. Even as President Dissanayake celebrated Thai Pongal in Jaffna to the appreciation of the people there, Malaiyaha Tamils engaged in peaceful campaigns to bring attention to their unresolved problems. In Colombo at the Liberty Roundabout, a number of them gathered to symbolically celebrate Thai Pongal while also bringing national attention to the issues of their community, in particular the problem of displacement after the cyclone.

The impact of the cyclone, and the likelihood of future ones under conditions of climate change, make it necessary for the displaced Malaiyaha Tamils to be found new places of residence. This is also an opportunity to tackle the problem of their landlessness in a comprehensive manner and make up for decades if not two centuries of inequity.

Planning for relocation and secure housing is good governance. This needs to be done soon. Climate related disasters do not respect political timetables. They punish delay and indecision. A government that prides itself on system change cannot respond to such challenges with temporary fixes.

The government appears concerned that finding new places for the Malaiyaha Tamil people to be resettled will lead to land being taken away from plantation companies which are said to be already struggling for survival. Due to the economic crisis the country has faced since it went bankrupt in 2022, the government has been deferential to the needs of company owners who are receiving most favoured treatment. As a result, the government is contemplating solutions such as high rise apartments and townhouse style housing to minimise the use of land.

Such solutions cannot substitute for a comprehensive strategy that includes consultations with the affected population and addresses their safety, livelihoods and community stability.

Lose Trust

Most of those who voted for the government at the last elections did so in the hope that it would bring about system change. They did not vote for the government to reinforce the same patterns that the old system represented. At its core, system change means rebalancing priorities. It means recognising that economic efficiency without social justice is a short-term gain with long-term costs. It means understanding that unresolved ethnic grievances, unaddressed wartime abuses and unequal responses to disaster will eventually undermine any development programme, no matter how well designed. Governance that postpones difficult decisions may buy time, but lose trust.

The coming year will therefore be decisive. The government must show that its commitment to non racism and inclusion extends beyond conflict prevention to conflict resolution. Addressing conflict related abuses, concluding long standing detentions, returning land, accounting for the missing and securing dignified resettlement for displaced communities are not distractions from the government programme. They are central to it. A government committed to genuine change must address the problems it inherited, or run the risk of being overwhelmed when those problems finally demand settlement.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Education. Reform. Disaster: A Critical Pedagogical Approach

This Kuppi writing aims to engage critically with the current discussion on the reform initiative “Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025,” focusing on institutional and structural changes, including the integration of a digitally driven model alongside curriculum development, teacher training, and assessment reforms. By engaging with these proposed institutional and structural changes through the parameters of the division and recognition of labour, welfare and distribution systems, and lived ground realities, the article develops a critical perspective on the current reform discourse. By examining both the historical context and the present moment, the article argues that these institutional and structural changes attempt to align education with a neoliberal agenda aimed at enhancing the global corporate sector by producing “skilled” labour. This agenda is further evaluated through the pedagogical approach of socialist feminist scholarship. While the reforms aim to produce a ‘skilled workforce with financial literacy,’ this writing raises a critical question: whose labour will be exploited to achieve this goal? Why and What Reform to Education

This Kuppi writing aims to engage critically with the current discussion on the reform initiative “Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025,” focusing on institutional and structural changes, including the integration of a digitally driven model alongside curriculum development, teacher training, and assessment reforms. By engaging with these proposed institutional and structural changes through the parameters of the division and recognition of labour, welfare and distribution systems, and lived ground realities, the article develops a critical perspective on the current reform discourse. By examining both the historical context and the present moment, the article argues that these institutional and structural changes attempt to align education with a neoliberal agenda aimed at enhancing the global corporate sector by producing “skilled” labour. This agenda is further evaluated through the pedagogical approach of socialist feminist scholarship. While the reforms aim to produce a ‘skilled workforce with financial literacy,’ this writing raises a critical question: whose labour will be exploited to achieve this goal? Why and What Reform to Education

In exploring why, the government of Sri Lanka seeks to introduce reforms to the current education system, the Prime Minister and Minister of Education, Higher Education, and Vocational Education, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, revealed in a recent interview on 15 January 2026 on News First Sri Lanka that such reforms are a pressing necessity. According to the philosophical tradition of education reform, curriculum revision and prevailing learning and teaching structures are expected every eight years; however, Sri Lanka has not undertaken such revisions for the past ten years. The renewal of education is therefore necessary, as the current system produces structural issues, including inequality in access to quality education and the need to create labour suited to the modern world. Citing her words, the reforms aim to create “intelligent, civil-minded citizens” in order to build a country where people live in a civilised manner, work happily, uphold democratic principles, and live dignified lives.

Interpreting her narrative, I claim that the reform is intended to produce, shape, and develop a workforce for the neoliberal economy, now centralised around artificial intelligence and machine learning. My socialist feminist perspective explains this further, referring to Rosa Luxemburg’s reading on reforms for social transformation. As Luxemburg notes, although the final goal of reform is to transform the existing order into a better and more advanced system: The question remains: does this new order truly serve the working class? In the case of education, the reform aims to transform children into “intelligent, civil-minded citizens.” Yet, will the neoliberal economy they enter, and the advanced technological industries that shape it, truly provide them a better life, when these industries primarily seek surplus profit?

History suggests otherwise. Sri Lanka has repeatedly remained at the primary manufacturing level within neoliberal industries. The ready-made garment industry, part of the global corporate fashion system, provides evidence: it exploited both manufacturing labourers and brand representatives during structural economic changes in the 1980s. The same pattern now threatens to repeat in the artificial intelligence sector, raising concerns about who truly benefits from these education reforms

That historical material supports the claim that the primary manufacturing labour for the artificial intelligence industry will similarly come from these workers, who are now being trained as skilled employees who follow the system rather than question it. This context can be theorised through Luxemburg’s claim that critical thinking training becomes a privileged instrument, alienating the working class from such training, an approach that neoliberalism prefers to adopt in the global South.

Institutional and Structural Gaps

Though the government aims to address the institutional and structural gaps, I claim that these gaps will instead widen due to the deeply rooted system of uneven distribution in the country. While agreeing to establish smart classrooms, the critical query is the absence of a wide technological welfare system across the country. From electricity to smart equipment, resources remain inadequate, and the government lags behind in taking prompt initiative to meet these requirements.

This issue is not only about the unavailability of human and material infrastructure, but also about the absence of a plan to restore smart normalcy after natural disasters, particularly the resumption of smart network connections. Access to smart learning platforms, such as the internet, for schoolchildren is a high-risk factor that requires not only the monitoring of classroom teachers but also the involvement of the state. The state needs to be vigilant of abuses and disinformation present in the smart-learning space, an area in which Sri Lanka is still lagging. This concern is not only about the safety of children but also about the safety of women. For example, the recent case of abusive image production via Elon Musk’s AI chatbox, X, highlights the urgent need for a legal framework in Sri Lanka.

Considering its geographical location, Sri Lanka is highly vulnerable to natural disasters, the frequency in which they occur, increasing, owing to climate change. Ditwah is a recent example, where villages were buried alive by landslides, rivers overflowed, and families were displaced, losing homes that they had built over their lifetimes. The critical question, then, is: despite the government’s promise to integrate climate change into the curriculum, how can something still ‘in the air ‘with climate adaptation plans yet to be fully established, be effectively incorporated into schools?

Looking at the demographic map of the country, the expansion of the elderly population, the dependent category, requires attention. Considering the physical and psychological conditions of this group, fostering “intelligent, civic-minded” citizens necessitates understanding the elderly not as a charity case but as a human group deserving dignity. This reflects a critical reading of the reform content: what, indeed, is to be taught? This critical aspect further links with the next section of reflective of ground reality.

Reflective Narrative of Ground Reality

Despite the government asserting that the “teacher” is central to this reform, critical engagement requires examining how their labour is recognised. In Sri Lanka, teachers’ work has long been tied to social recognition, both utilised and exploited, Teachers receive low salaries while handling multiple roles: teaching, class management, sectional duties, and disciplinary responsibilities.

At present, a total teaching load is around 35 periods a week, with 28 periods spent in classroom teaching. The reform adds continuous assessments, portfolio work, projects, curriculum preparation, peer coordination, and e-knowledge, to the teacher’s responsibilities. These are undeclared forms of labour, meaning that the government assigns no economic value to them; yet teachers perform these tasks as part of a long-standing culture. When this culture is unpacked, the gendered nature of this undeclared labour becomes clear. It is gendered because the majority of schoolteachers are women, and their unpaid roles remain unrecognised. It is worth citing some empirical narratives to illustrate this point:

“When there was an extra-school event, like walks, prize-giving, or new openings, I stayed after school to design some dancing and practice with the students. I would never get paid for that extra time,” a female dance teacher in the Western Province shared.

I cite this single empirical account, and I am certain that many teachers have similar stories to share.

Where the curriculum is concerned, schoolteachers struggle to complete each lesson as planned due to time constraints and poor infrastructure. As explained by a teacher in the Central Province:

“It is difficult to have a reliable internet connection. Therefore, I use the hotspot on my phone so the children can access the learning material.”

Using their own phones and data for classroom activities is not part of a teacher’s official duties, but a culture has developed around the teaching role that makes such decisions necessary. Such activities related to labour risks further exploitation under the reform if the state remains silent in providing the necessary infrastructure.

Considering that women form the majority of the teaching profession, none of the reforms so far have taken women’s health issues seriously. These issues could be exacerbated by the extra stress arising from multiple job roles. Many female teachers particularly those with young children, those in peri- or post-menopause stages of their life, or those with conditions like endometriosis may experience aggravated health problems due to work-related stress intensified by the reform. This raises a critical question: what role does the state play in addressing these issues?

In Conclusion

The following suggestions are put forward:

First and foremost, the government should clearly declare the fundamental plan of the reform, highlighting why, what, when, and how it will be implemented. This plan should be grounded in the realities of the classroom, focusing on being child-centred and teacher-focused.

Technological welfare interventions are necessary, alongside a legal framework to ensure the safety and security of accessing the smart, information-centred world. Furthermore, teachers’ labour should be formally recognised and assigned economic value. Currently, under neoliberal logic, teachers are often left to navigate these challenges on their own, as if the choice is between survival or collapse.

Aruni Samarakoon teaches at the Department of Public Policy, University of Ruhuna

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Aruni Samarakoon

Features

Smartphones and lyrics stands…

Diliup Gabadamudalige is, indeed, a maestro where music is concerned, and this is what he had to say, referring to our Seen ‘N’ Heard in The Island of 6th January, 2026, and I totally agree with his comments.

Diliup Gabadamudalige is, indeed, a maestro where music is concerned, and this is what he had to say, referring to our Seen ‘N’ Heard in The Island of 6th January, 2026, and I totally agree with his comments.

Diliup: “AI avatars will take over these concerts. It will take some time, but it surely will happen in the near future. Artistes can stay at home and hire their avatar for concerts, movies, etc. Lyrics and dance moves, even gymnastics can be pre-trained”.

Yes, and that would certainly be unsettling as those without talent will make use of AI to deceive the public.

Right now at most events you get the stage crowded with lyrics stands and, to make matters even worse, some of the artistes depend on the smartphone to put over a song – checking out the lyrics, on the smartphone, every few seconds!

In the good ole days, artistes relied on their talent, stage presence, and memorisation skills to dominate the stage.

They would rehearse till they knew the lyrics by heart and focus on connecting with the audience.

Smartphones and lyrics stands: A common sight these days

The ability of the artiste to keep the audience entertained, from start to finish, makes a live performance unforgettable That’s the magic of a great show!

When an artiste’s energy is contagious, and they’re clearly having a blast, the audience feeds off it and gets taken on an exciting ride. It’s like the whole crowd is vibing on the same frequency.

Singing with feeling, on stage, creates this electric connection with the audience, but it can’t be done with a smartphone in one hand and lyrics stands lined up on the stage.

AI’s gonna shake things up in the music scene, for sure – might replace some roles, like session musicians or sound designers – but human talent will still shine!

AI can assist, but it’s tough to replicate human emotion, experience, and soul in music.

In the modern world, I guess artistes will need to blend old-school vibes with new tech but certainly not with smartphones and lyrics stands!

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective