Midweek Review

Vision for a Holistic Education

Closer Connections among Different Branches of Human Knowledge:

by Liyanage Amarakeerthi

(A shortened version of a plenary speech given by Prof. Amarakeerthi at the International Conference of Sabaragamuwa University, Sri Lanka, on 03 December)

Every year I teach a course in aesthetics and non-linguistic arts. In that, I discuss what we ‘get’ from visual art works such as painting. One of the difficulties I constantly have is to explain to my students what they gain from looking at a painting, watching a dance performance, or listening to a piece of music.

Getting something out of art is a tricky business. Visual arts appeal to our eyes and through that sensory agent, a painting creates a certain aesthetic effect on us. Alexander Baumgarten, the first philosopher to open up the field what is now called “aesthetics”, thought that human beings gain a certain knowledge of themselves and the world through aesthetic objects. That knowledge is, he argued, acquired through our senses, eyes, ear, skin, tongue. This bodily perception he thought is inferior to rational knowledge. For him, only the rational mind can produce superior knowledge. In his book, Aesthetica (1750), he famously said, ” Aesthetics is the sister of logic.” One can easily see the Cartesian separation of mind and body here. Descartes’ has it that, “I think, therefore I am.” Here think means, logical thinking, the activity of the mind. But the ‘aesthetic cognition’ of Baumgarten was about bodily perception, about what we feel with our senses. Descartes or card-carrying Cartesians would never say, “I feel, therefore, I am.”

In the Western discussions about knowledge after Descartes, a tragic separation of the rational mind and emotional body takes place and it has continued to exist and widen despite numerous attempts to bridge it. My speech today is about creating points of contact across this divide. This is not a new theme in the scholarly discussions, of course, but in Sri Lanka this requires much more attention.

Professor Antonio Damasio has demonstrated in his excellent book, Descartes’ Error, maintains that the mind/body separation was a mistake made in the rationalist tradition. According to him, rational thoughts and emotions nurture and supplement each other. In fact, it is in the fertile ground of emotions that rational thought achieves its richest form. Damasio claims in the fields of neuroscience and biochemistry emotions have been given the due place they disserve: “Contrary to traditional scientific opinion, feelings are just as cognitive as percepts”(xxv). After all, it might not all that wrong to call, ” I feel, therefore, I am.”

Taking cue from scientists

Taking a cue from scientists like Damasio, I think that these new developments in natural sciences can be wisely used to create a new dialogue between sciences and the humanities, the latter being often regarded as fields that deal with human emotions.

In a striking paragraph in their Primordial Bond, Stephen Schneider and Lynn Morton state,

“Along with the attempt to separate himself from Nature, man has also separated himself from his fellow man. We have subdivided ourselves into groups: professions, nationalities, religions, sexes, and even intellectual sectors like artists and scientists”(1981, 21).

Separations of this kind might be somewhat conceptual in the West, here, in Sri Lanka, the separation is physical, social, and even political. It is physical in the sense that those of us who are in these separate subject areas are physically distanced from each other as exemplified in the way different faculties are separated at the best-planned university, Peradeniya. The separation is social because those who have the expertise in different subjects are hierarchically organized – doctors at the top and others are bellow at different degrees. At least in the public imagination, this is usually the case. That separation is political in the sense powerful trade unions of doctors to continue to the get the lion’s share from the country economy. Remember, those were the ones who go the lion’s share of the country’s education in the first place.

This kind of intellectual or cultural attitudes are absent, at least in a crude form like the above, in countries where the idea of liberal arts has persisted for centuries. A typical liberal arts curriculum includes natural sciences, mathematics, history, literature, economics, languages, fine arts and so on. All these subjects are taught all the way up the university entrance level. At the university, students are required to take humanities and social science courses no matter what subject they are going to major in. For example, to get into the medical school, one has to pass some pre-med courses which typically include the following: Biology, biochemistry, calculus, ethics, psychology, sociology, statistics, genetics, humanities, public health, and human physiology.

As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, I have met pre-med students and students from the School of Engineering, and the Business School taking courses in literature, drama and philosophy at the school of Arts and Sciences.

Even this long tradition of liberal arts in such powerful countries has been under threat in recent times. But when that happens over there, numerous educationists come forward to defend that concept of holistic education. One such scholar, Mark William Roche wrote an excellent book, Why Choose the Liberal Arts? when the idea of holistic education came under attack nearly decade ago. Let me quote a paragraph that might resonate with all of you: “Liberal arts students are encouraged to develop not only an awareness of knowledge intrinsic to their major but a recognition of what that discipline’s position within the larger mosaic of knowledge. The college or university citizen invested in the search for not only specialized knowledge but also the relation of the diverse parts of knowledge to one another. To be liberally educated involves knowing the relative position of the little one knows within the whole knowledge. Mathematics helps us see the basic structures and complex patterns of the universe, and the sciences help us understand and analyze the laws that animate the natural world, the inner world, and the social world. History opens a window onto the development of the natural and social world. The intellectual fruits of arts and literature, the wisdom of religion, and the ultimate questions of philosophy illuminate for us the world as it should be. In essence, the arts and sciences explore the world as it is and the world as it should be (pp. 21-2).

A rethink needed

In Sri Lanka too, it is time for us to reconsider the separation of various branches of knowledge and to imagine the ways by which we can reconnect- most rewarding ways to reconnect. Regular discussions with some of my colleagues in natural sciences at Peradeniya, and engineering have convinced me that there are so many intelligent and creative people on the other side of the divide, eagerly waiting to hold on to a friendly hand extended from our side.

This does not mean that the disciplinary hierarchies within the world of education have suddenly fallen down, and all have become equals. That is hardly the case. The subordination of all other subjects to natural sciences still continues. Publishing industry, funding mechanisms, ranking systems, the methods of rewarding scholars are more or less dominated by the scientific way of thinking. Scientism, that is elevating science to an object of worship, is also visible.

But still it is worthwhile for those of us in the humanities to engage in discussions at least with some branches of natural science. In fact, I think that, as a first step towards initiating this dialogue, everyone enters the faculties of arts should be provided with opportunities to learn the basics of science. In addition, a course in philosophy of science will show them both potentials and the limits of science.

A Union of Nature and Culture

Already, in cultural studies, there is a closer dialogue between natural sciences and social sciences in the effort understand how much of our ways of being in the world owes to nature and how much can be attributed to culture, and more importantly how much of culture gets into our psyche during the course of evolution or history. The way we carry ourselves in the world has been determined by both culture and Nature. Much of human nature is in that sense both cultural and natural.

Constructivism

Cultural constructivism had a major blow after that famous Canadian experiment in 1960s failed. Let me remind you that famous case. When a Canadian baby boy being circumcised, a doctor accidentally cuts off a large part of the boy’s penis. It was the heyday of cultural constructivism and the baby’s parents and the doctors decided to remove the remaining part of the penis, and to turn the boy into a girl. The plan was to raise the child as a girl, and surgically change the penis into a vagina, and, when she comes to the age of puberty, they would give her required hormones to help her move into complete womanhood. The parents named her “Brenda.” Famous psychologist named John Money advised the doctors and parents about how culture constructs gender, and Brenda was raised as a girl. Her clothing, toys, games and so on all were the ones typically assigned to girls. But Brenda never felt at ease with any of these. She did not feel comfortable among girls. The carefully planned socialization program failed.

But the textbooks on gender difference instructed the parents that the project should succeed. John Money the psychologist did not want to admit that it was a failure because of the impact it was likely to have on his career. By the time, Brenda was going to be given hormone injections to transform her completely into a woman, she rebelled and the parents decided to tell her what really happened. Brenda gave up all her cultural identity of a woman and took a male name. Of course, he is unable to father children. He married a woman who had two children from a previous relationship and became the father to them.

Culture and socialisation

Culture and socialisation, two mechanisms, the constructivists thought could transform a boy into normal girl, failed making a huge impact on the constructivist school of thought. Our biological hardwiring and genes are so crucial in deciding who we are. The culture, society, ideology and the like are still important creating and sustaining our identities. A much finer understanding between natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities can help us get the bigger picture of being human. We might never understand the final or the most perfect picture of all realities of the humanity. One of the remarkable truths the study of genes reveals is that a minute genetic uniqueness can result in giving each of us a unique identity, and end up making us significantly different from each other. Culture and socialization can only strengthen, even overdetermine, that difference. Moreover, socialisation can make us see our shared humanity as well. One may recall here Simone de Beauvoir’s famous sentence, “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman”. (The Second Sex).

These scientists are not suggesting at all that we should return to biological determinism to argue, contrary to de Beauvoir’s point, that all the attributes of a woman are natural and she is born with them. No. We know much of what makes a woman is socio-culturally determined. But Brenda’s case invites us to come up with much richer understanding of nature/culture divide.

What I am suggesting here is that the humanities will certainly benefit by paying closer attention to some meticulous research in natural sciences. Yet, I am no expert to use scientific knowledge in a scientific manner. Therefore, what I am saying here might be incomplete and partial. But still, these facts, I hope, that make some sense.

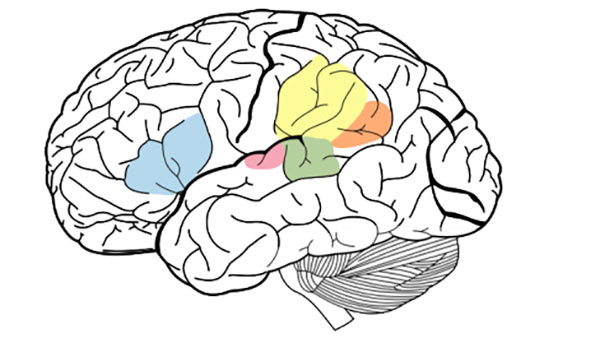

Amygdala, the Almond

Let me tell you about the story of Amygdala – a small segment of the human brain. In Greek, Amygdala means, ‘almond’ because it is what this particular part of the brain looks like. This small area of the brain is so crucial in determining human behavior, especially various behaviors related to aggression. We in the humanities and social sciences, often study causes of human aggression. In the field literature, we interpret aggressive behaviours looking into their social-cultural origins. We often use one person’s actions as windows into human action in general in a given social or historical contexts. I truly believe that scientific explanations about the workings of Amygdala reveals us certain realities of human life that we cannot ignore. Incorporated into our culturalist or behaviorist explanations about human affairs, these scientific revelations can deepen our understating of ourselves. Extreme naturalists too can learn one or two things from the humanities and social sciences.

Scientists have experimented with Amygdala for years using various animals in addition to human beings. When this particular portion of the brain is damaged or wounded by some scientific methods, rates of aggression in that animal significantly decline. Conversely, when the Amygdala is stimulated by implanting electrodes there, aggression of the animal increases. In humans too, scientists have found out that the functioning of amygdala is so crucial for aggressive behaviour.

Human aggression has some important pathological source, and by scientifically controlling Amygdala aggression can be controlled. In other words, surgery knife, electric shocks or injections can be more useful in suppressing riots than armies or police forces! Perhaps, that is already happening.

Robert Sapolsky discusses two cases, one from Germany and another from the US, where two perfectly normal people turning into gangsters and murderers simply because their amygdala is damaged. In the two cases, more than socio-cultural causes, the damaged amygdala was the most apparent reason for them to become what they later became. The whole story of two cases are the stuff of novels and films- things we regularly discuss in our classrooms, lecture halls and in our literary or cinematic criticism. We are more than likely to use these two cases as points of departure to embark on much larger socio-cultural analysis.

Not only aggression

Amygdala is related to many other emotions, mental traits and behaviors. Anxiety, fear, and certain phobias might have their origin in certain parts of amygdala. This part of the brain plays a crucial role in making social and emotional decisions. Even at the risk of this speech turning into a lesson in neurology, please allow me to cite some more examples.

When we accidentally chew on some rotten food, we instantly spit it out even before we could make a conscious decision of it. That is amygdala at work. A chemical reaction happens there, gets what is harmful to us out of our body. What is interesting for us is this: When see something morally disgusting such as woman being subjected to violence, the same chemical reaction takes place in amygdala and prompts us to take appropriate actions. Here amygdala and the frontal cortex of the brain work in unison to alert us about the right kind of behavior.

It is not surprising perhaps that amygdala gets activated by rotten food because it is nature’s way of protecting us from harm. But we activate amygdala when we think about morally disgusting things. Remember, when we think about them. In other words, a mental image of such a thing can still get us physically activated. Perhaps, this explains how and why literary works and films can move us into moral actions.

But there are ways this becomes complicated. These chemical reactions to disgust occur in the brain, for examples when accidentally chew on a cockroach or think about doing so. Things get still more complicated, my friends- still more complicated! Similar chemical reactions in our brain take place when we feel that a neighboring tribe, a group of people are like ‘loathsome cockroaches'(Sapolsky. Behave. 41-2). Now, you can see that neuro-chemistry in our bodies participate in our nationalism, racism and the self/other divide.

I do not want to argue here that nationalism, racism or political rivalry is all about a set of chemical-electric work within the body. I am just drawing your attention to the fact that our biochemistry has a significant role in our cultural, social and political life. No scientist, whose work I have studied so far claim that our culture, our social relations and so on are all about biochemistry. They certainly acknowledge the significance of socio-cultural contexts. In the concluding section to his monumental book, Behave, professor Sapolsky puts it four words: “Brains and cultures coevolve.” (672)

US and Them

Human beings, like some other animals, separate the world into Us and Them. This division often takes to be fundamentally cultural. Many of signs that are interpreted as US are indeed cultural. But the function of amygdala tells us something interesting. Us and Them separation may have a biological foundation. Explaining how empathy and brain are related, Sapolsky states,

“‘…Amygdala activates when viewing fearful faces, but only of in-group members; when it is an out-group member, them showing fear even might be good news — if it scares Them, bring it on”(395).

In winding up, this speech, let me repeat my main argument: The isolation of different branches of knowledge from each other has been a perennial problem in our education. Specialized knowledge is important indeed. But still there must be intense discussions among those fields because for a holistic understanding of our lives, societies, and the world can only be arrived at by attempting to create an organic whole in which each field of knowledge has a gap to fill. Where the gap is seemingly filled by one branch of knowledge, still other branches of knowledge might be able to fortify filling even further. And there may be certain gaps the humanity will never fill, and that is where we need much more engaged discussion among ourselves.

In this speech, I suggested that liberal arts model followed in the US and elsewhere, could guide us to think of model of our own to integrate various forms of knowledge. To begin this process of integration, those of us in the humanities should consider the ground-breaking new research, some of which, I have summarized above. Those of us in the natural sciences too need to learn the art of writing science in a manner that can be understood by the non-specialists.

(Amarakeerthi is professor of Sinhala at University of Peradeniya)