Features

Under 18 Young Magicians Contest on October 25

The Sri Lanka Magic Circle has, over the years, preserved the performing art of magic and produced top magicians since February 18, 1922.

The Circle now mainly concentrates on promoting the art to youngsters and offer free training classes on every second Sunday afternoon and conducts a Members’ Day in the morning of every last Sunday of the month.

Regular training sessions on presentation, patter, pantomime, showmanship, stagecraft, audience appeal and entertainment values are conducted by award winning professional magicians. Even adults interested in magic can join the group!

Magic Contests for Rope, Coins, Card and Silk were held on August 30 at its headquarters ‘Vishmithapaya’, 156, Templers Road, Mt. Lavinia, in the presence of an audience. Two young school-going teenagers performed skillfully at an entertainment program after being trained every second Sunday of the month.

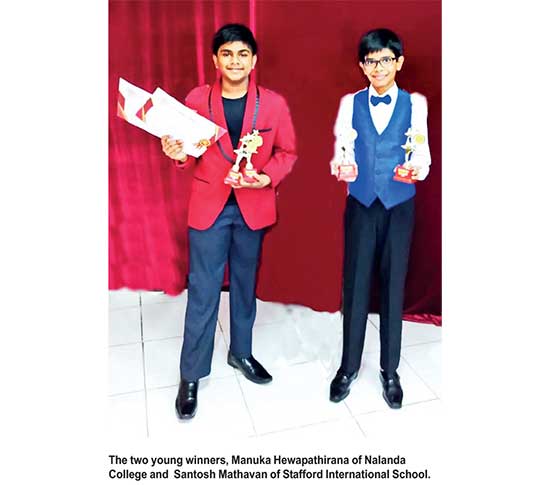

Manuka Hewapathirana of Nalanda College was adjudged the winner of the Rope and Coin Magic contests, while Santosh Mathavan of Stafford International School won the Cards and Silk Magic Contests.

The trophies were donated by Vice President Asanka Pathirana. Rohan Jayasekera (President), Sanjeeva Hewapathirana (Trainer) Kalabushana Chandrasena Gamage and Kalakeerthi Ronald de Alwis (President Emeritus) presented the awards.

The under 18 Young Magicians Contest will be held on October 25 for the coveted Magician of the Year 2020 Gate Mudaliyar A. C. G. S. Amarasekera Challenge Shield and the 2020 Master Magician for the Ranapala Bodinagoda Challenge Trophy.

Seats reserved on a first-come-first-served basis. As seats are limited, call Rohith J. Silva on 0777587112 for reservations. Wearing a face mask is mandatory.

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

Features

Why does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (FCEJ) is outraged at the scheme of law proposed by the government titled “Protection of the State from Terrorism Act” (PSTA). The draft law seeks to replace the existing repressive provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979 (PTA) with another law of extraordinary powers. We oppose the PSTA for the reason that we stand against repressive laws, normalization of extraordinary executive power and continued militarization. Ruling by fear destroys our societies. It drives inequality, marginalization and corruption.

Our analysis of the draft PSTA is that it is worse than the PTA. It fails to justify why it is necessary in today’s context. The PSTA continues the broad and vague definition of acts of terrorism. It also dangerously expands as threatening activities of ‘encouragement’, ‘publication’ and ‘training’. The draft law proposes broad powers of arrest for the police, introduces powers of arrest to the armed forces and coast guards, and continues to recognize administrative detention. Extremely disappointing is the unjustifiable empowering of the President to make curfew order and to proscribe organizations for indefinite periods of time, the power of the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence to declare prohibited places and police officers in the rank of Deputy Inspector Generals are given the power to secure restriction orders affecting movement of citizens. The draft also introduces, knowing full well the context of laws delays, the legal perversion of empowering the Attorney General to suspend prosecution for 20 years on the condition that a suspect agrees to a form of punishment such as public apology, payment of compensation, community service, and rehabilitation. Sri Lanka does not need a law normalizing extraordinary power.

We take this moment to remind our country of the devastation caused to minoritized populations under laws such as the PTA and the continued militarization, surveillance and oppression aided by rapidly growing security legislation. There is very limited space for recovery and reconciliation post war and also barely space for low income working people to aspire to physical, emotional and financial security. The threat posed by even proposing such an oppressive law as the PSTA is an affront to feminist conceptions of human security. Security must be recognized at an individual and community level to have any meaning.

The urgent human security needs in Sri Lanka are undeniable – over 50% of households in the country are in debt, a quarter of the population are living in poverty, over 30% of households experience moderate/severe food insecurity issues, the police receive over 100,000 complaints of domestic violence each year. We are experiencing deepening inequality, growing poverty, assaults on the education and health systems of the country, tightening of the noose of austerity, the continued failure to breathe confidence and trust towards reconciliation, recovery, restitution post war, and a failure to recognize and respond to structural discrimination based on gender, race and class, religion. State security cannot be conceived or discussed without people first being safe, secure, and can hope for paths towards developing their lives without threat, violence and discrimination. One year into power and there has been no significant legislative or policy moves on addressing austerity, rolling back of repressive laws, addressing domestic and other forms of violence against women, violence associated with household debt, equality in the family, equality of representation at all levels, and the continued discrimination of the Malaiyah people.

The draft PSTA tells us that no lessons have been learnt. It tells us that this government intends to continue state tools of repression and maintain militarization. It is hard to lose hope within just a year of a new government coming into power with a significant mandate from the people to change the system, and yet we are here. For women, young people, children and working class citizens in this country everyday is a struggle, everyday is a minefield of threats and discrimination. We do not need another threat in the form of the PSTA. Withdraw the PSTA now!

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice is a collective of feminist economists, scholars, feminist activists, university students and lawyers that came together in April 2022 to understand, analyze and give voice to policy recommendations based on lived realities in the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Please send your comments to – feministcollectiveforjustice@gmail.com

Features

A case study on the functioning of Govt.and fraudulent school admissions

It is interesting how on occasions, a relatively trivial incident can take on large significance and waste the time and attention of several, even senior, public servants. One such incident was President Premadasa’s visit to St. Bernadette’s College, Polgahawela to preside over a prize-giving.

The well established system in the Ministry was that invitations to the President to preside at school prize-givings were referred by the Presidential Secretariat to the Ministry for advice. The Ministry, taking into account all relevant factors including the importance of the President’s time, recommended acceptance or rejection. If the President accepted the Ministry recommendation to participate, the Presidential Secretariat kept the Ministry informed of such participation.

It was then the duty of the Ministry to ensure that either the Minister or a Project or the State Minister and a senior official attended the function. This was in addition to anyone attending from the Provincial Ministry of Education. The President required this attendance, in case he needed to check on any facts or figures.

In the case of St. Bernadette’s the President found when he went there, that there was no representation at all from the Ministry. The prize-giving was on a Saturday, and there was a big splash in the Sunday papers about the President’s attendance and speech. When I went to office on Monday, I did not suspect that there was anything amiss. In the early part of the morning I was chairing a meeting when I received a call from Mr. K.H.J. Wijayadasa, Secretary to the President.

From his tone it was evident that he was both irritated and exasperated. He inquired as to why no Minister or official from the Ministry was present at St. Bernadette’s on Saturday. He said that the President was furious and that he was having no peace. Every few minutes, he was telephoning and disturbing him. “I came today with the intention of finishing some important work in the morning. I now find I can’t do a thing,” Mr. Wijayadasa complained with obvious frustration.

He wanted an immediate report phoned in to him. That was the end of my important work too. I was also working to a tight schedule and wanted to accomplish much that morning. Everything now had to be abandoned to chase after a matter of no consequence at all to the country. Inquiries showed that the Ministry had no record of a request from the Presidential Secretariat. My senior Additional Secretary, Mrs. Kamala Wickremasinghe, a diligent, competent and responsible officer who dealt with this area, assured me that she had received no intimation at all of this Prize-giving.

I had no recollection of anything passing my table either. We were trying to get to the bottom of this mystery. Mr. Wijayadasa kept on ringing, getting more and more irritated because the President was ringing him demanding an explanation. This was now turning out to be a minor nightmare, fortified with something of a comic element.

By now several senior officers had suspended all other work and were engaged in detective work, trying to find out what happened. I was totally immobilized coping with Mr. Wijayadasa demanding answers on one side and chasing after my officers on the other. Mr. Wijayadasa was immobilized because the President was not allowing him any peace of mind to attend to his work.

Eventually, after almost two tense and unpleasant hours we discovered the unsuspecting culprit. It was the Minister (Mr. Athulathmudali). What had happened was that some Members of Parliament, representing the area had met the Minister in his room in Parliament and had obtained the Minister’s hand-written approval on a note submitted to him. The Minister kept no copy. Therefore, nothing passed down to the office.

The MPs concerned would have then dealt with the President’s personal staff. Therefore, neither Mr. Wijayadasa nor his officials knew anything. We didn’t know either. This entire episode was not only an example of what fairly frequently happens in government where matters of no great national consequence have to be given urgent attention at the expense of extremely important matters.

It was also a demonstration of the importance of proper information flows, documentation and lines of communication in working a system. If for some reason, the system is short circuited, disaster could follow. That is why the proper keeping of records in a civil service is vitally important.

Computers in schools

One of the many important issues that had to be addressed was the one of providing computers to schools. When we went into the Ministry we found that there was a Cabinet decision to provide computers to schools, principally to be used by “A” level pupils. This immediately struck me as being impractical. Children grappling with four difficult subjects at the “A” level in an environment of intense competition to enter our Universities were already overwhelmed with their studies.

The reality was that a great many of them also attended various tuition classes during their spare time. They were not required to use computers as a part of their normal work. It was therefore extremely unlikely that they had any time or energy left to follow instructions on the use of computers, and thereafter put in the hands on practice that was necessary.

I decided to probe this matter. It came as no surprise to me that things were happening in just the way I had imagined. Some schools had computers given to them for use in “A” level classes. But there was no time to conduct classes. The computers were therefore safely locked up! The Ministry had a Computer Advisory Council. I immediately re-constituted it and re-activated it.

On it I had persons of the calibre of Professor Samaranayake of the Colombo University and at the time Chairman of CINTEC; Professor Induruwe of Moratuwa University; Professor Thilakaratne of the Kelaniya University; and other well-known computer academics and professionals. The Council totally agreed with my diagnosis of the problem.

I froze the purchase of computers under the Cabinet decision and appointed a subcommittee of the Computer Advisory Council to study and make recommendations as to the use of computers in schools. I kept the Minister informed. He heartily approved of the action taken. The sub-committee report which was handed over within about four months recommended the setting up of computer centres in strategically identified schools, catering not only to those schools, but to a cluster of surrounding schools.

They also made the important recommendation that the computer classes and courses should be targeted towards those children who had finished sitting for their “O” level and “A” level examinations, and had nothing to do pending results. These recommendations were accepted by the Minister. We then worked on curricula, duration of courses, equipping the centres, training of teachers and instructors and other relevant matters.

I particularly insisted that the courses provided at these centres should not be “dead end” courses leading to nowhere. I wanted them structured in such a way that those successfully completing them could obtain the necessary exemptions and credits, if they wished to pursue their studies further and sit for national and international examinations. This was done.

We started three pilot projects, including in the Monaragala and Matara districts. The enthusiasm of both parents and children was very great. In one school centre the parents voluntarily built a shed with their own funds to shelter children waiting for one batch to come out, in order to go in and start their own classes. The number of these centres gradually grew, and by the middle of 1990, they totaled around 14 catering to thousands of children.

Education Development Cell

As we proceeded there was another issue that caused me concern. Being a large Ministry, the flow of files, paper and reports reaching me was very heavy. Given my various responsibilities, the number of meetings, conferences and tender boards I had to attend also took much time. At a certain point I began to realize that most if not all of my time was spent on attending to and clearing up matters that the system threw up. There was no serious thinking going on in a coherent and co-ordinated way about quality improvement in the system, which would also have to lead to a close scrutiny of the system as it existed and a questioning of the assumptions on which it rested.

Some of this did take place in the fora of discussion on assistance to education by institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian development Bank. Multidisciplinary teams from these institutions and others sat with us at a number of meetings and at discussions which went on for hours. These were helpful, due to the complexity and variety of matters that were raised. They helped immensely to clarify our own thinking on a number of important matters such as curricula, teacher training, examinations, book development, proper costing and so on.

But here again, we were not entirely in control of the agenda. We were reacting to external impulses. I therefore thought that it was very important for us to establish internal control of the education agenda and to create some space for independent thinking among ourselves. I therefore decided to establish in the Ministry what I called an “Education Development Cell,” with officers being hand picked for their knowledge, experience, attitudes and capacity to think. I deliberately kept the numbers small, because itis difficult to have meaningful discussions in a large body.

The numbers varied from 10 to 12. I also had to find a suitable time to meet, given the pressure on my own time. We settled on 5 p.m. although on some days I was unable to start the proceedings before 5.30 p.m. or so. To the great credit of this group consisting of some of my additional Secretaries and senior educationists they participated with great interest, diligence and patience. On some days even when the time was 7.30 p.m. there was no impatience shown, and concentration did not flag.

They, as well as in my personal experience, hundreds of others gave the lie to the broad and irresponsible assertion that public servants are “clock watchers” and that because they had security of tenure and a regular salary, they shirked and did not work. There are of course such individuals as is bound to happen in a large system. But to accuse the public service as a whole in such a manner was demonstrably unwarranted and even reckless.

The discussions we had in this group consisted mainly of examining the quality, relevance and reach of the numerous programmes and the exploration of possibilities of improvement, through appropriate amendments, extensions or sometimes even replacements. The group also studied issues relating to regular and relevant training, cost savings, resourcing, improving systems and so on. Emphasis was also laid on the modalities of converting decisions made by us into the stream of actual implementation followed by monitoring feed-back and further assessment. The meetings were both productive and interesting, characterized by spirited discussions and much good humour, and were looked forward to by all.

Admission to Year One and Fraud

One of the salutary instructions that was issued by Minister Lalith Athulathmudali related to admission to schools in year one. There was tremendous pressure on the Ministry and on principals

of schools from parents as well as from various other sources including political forces to admit children to the more recognized and popular schools in particular. Pressure was applied through

letters, telephone calls, repeated personal visits and so on. All these constituted a significantly disturbing factor to all those at the receiving end who included the Minister and the Secretary.

The Minister therefore, issued an order that no one in the Ministry should intervene in an admission. No officer in the Ministry was to issue any letters, or in any other way bring to bear pressure on principals in the area of admission. Principals were free to follow strictly, the prevailing circular instructions. Any parent or other party seriously aggrieved with the decision of a principal could seek a remedy in the courts, after the Appeals Board procedure was exhausted. There was to be no administrative interference whatsoever.

I was therefore quite taken aback when the Principal of Nalanda College, Mr. Dharma Gunasinghe, rang me one day and rather hesitantly and apologetically informed me that in respect of my “note” to him, he had managed to enter one child to year one. He was however finding some difficulties in entering the second, but would try his best to admit him also. I immediately said “Surely, aren’t you aware that we don’t interfere in these matters at all? I have sent you no letters at all.”

Mr. Gunasinghe then said, “Sir, your signature is on this letter.” I asked him “How do you know it is my signature?” Then only did he begin to realize what had happened. I was about to leave the Ministry to attend a meeting. I instructed him to send under confidential cover and through a reliable messenger the letter concerned, to my office immediately. I then told my personal assistant that I was expecting an urgent hand delivered letter from the principal of Nalanda College, and that he should take over this letter and keep it securely unopened until I got back from my meeting.

I then telephoned my Senior Additional Secretary Mrs. Wickremasinghe and to her evident shock narrated what had happened, and instructed her to personally call the Deputy Inspector General of Police, CID and request him to send an officer immediately to the Ministry. I said that I would be back within one and a half hours after my meeting. When I came back a CID officer was awaiting me. I looked at the letter. It was typed on a Ministry letterhead with the rubber seal “Secretary Ministry of Education and Higher Education,” impressed at the bottom. Just above was a very badly forged signature. The perpetrator had not taken the trouble to make any study of my signature.

The signature was “Dharmasiri Pieris” I never sign like that except in writing to personal friends. In fact my normal signature was an indecipherable oddity which afforded some amusement to my friends, to the point of some of them asking, “Is that a signature?” To this my customary reply was “Anything can be a signature as long as one is consistent.” The CID inspector had not been idle until I came. He brought the rubber stamp from my office and impressed it on a piece of paper. He then showed the paper to me and said “See here Sir, your office seal has got wasted through use.”

The wastage was clearly visible. Some of the letters were not sharp or very clear. Then he pointed to the seal used on the forged letter. All the letters were fresh, bright and clear. “He has got a seal cut,” the inspector said. Thereupon, he recorded my statement and went on recording the statements of various others in my private office and the Ministry. Ultimately one of my office aides was arrested as well as the main culprit who was a conman who had been posing off as a Provincial Councilor and in that bogus capacity visiting the Ministry regularly in order to particularly deal with school admission matters.

He had come to see me as well, and looked a most plausible Provincial Councilor. The CID found that he had used my forged signature to admit four children to leading schools, including one child to a leading girls’ school. His fee had been Rs. 35,000 per child. When the parents inevitably would have negotiated for a reduction, he no doubt told them that a large part of it went to the Secretary.

The case came up before High Court Judge Colombo Mrs. Shirani Tilakawardena. On the first day the case couldn’t proceed because the State Counsel was not ready with all the reports, etc. He was roundly ticked off by the Judge. She then warned Counsel for the defense that she considered this an extremely serious case and that when the Examiner of Questioned Documents’ report came in, he should consider his clients plea very carefully.

The trial was then fixed for another day. On that day the accused pleaded guilty and received a suspended prison sentence of five years. Some of my colleagues in the Ministry thought that he should have spent some real time in jail. I was satisfied that he was caught and dealt with before much damage could be done. There only remained one other matter. What were we to do about the children who entered school through payment to this man.

After reflection and discussion also with the Minister, we decided not to do anything. We regarded the children concerned as victims or (beneficiaries?) of a process that was beyond them. We did not wish to cause them any trauma.

(Excerpted from In Pursuit of Governance, by MDD Peiris)

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGiants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan