Features

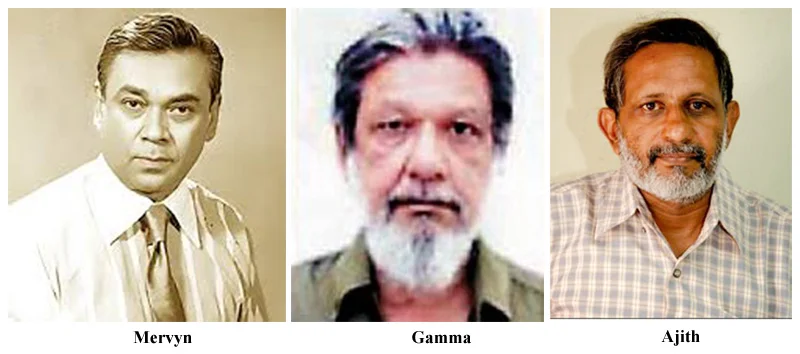

Three Great Editors: Mervyn, Gamma and Ajith

Journalism Awards for Excellence – 25th Anniversary

by Dayan Jayatilleka, PhD

(Reproduced from the souvenir for 25th Journalism Awards for Excellence ceremony to be held today.)

MERVYN

Mervyn de Silva

has been described as “the greatest journalist that Sri Lanka ever produced” (Radhika Coomaraswamy, 2001). Furthermore, “… [Mervyn’s] literary critical writing…and his affirmative humanism that grew from it enriched the world of journalism in Sri Lanka as no one else has done.” (Godfrey Gunatilleke, 2005).

Mervyn began as a free-lancer, joined the profession as a cub-reporter, became Deputy Editor, Observer, and reached the top as Editor Daily News and Editor-in-Chief. Choosing to remain in Sri Lanka declining lucrative job offers in journalism overseas, he made his mark in the elite international media as Colombo’s correspondent for the BBC, The Economist (London), the Financial Times (London), Times of India and India Today.

An unmatched achievement in Sri Lanka, Mervyn became the Editor-in-Chief of the two largest, rival journalistic establishments of the day: Lake House and The Times Group.

He was not only a print journalist, but also a veteran radio journalist, a broadcaster with programmes on literature (‘Off My Bookshelf’) and foreign affairs, running for decades. He also had a world affairs programme on Rupavahini TV in which he was the ‘talking head’ interviewed by Eric Fernando.

He wrote influentially on national politics while it was widely acknowledged that “No one was more aware of international affairs than Mervyn de Silva…one of the pioneer intellectuals of non-alignment” (Radhika Coomaraswamy 2001).

In print journalism he excelled in diverse roles, as a critic on literature and film, as columnist from his earliest days in journalism, ‘Daedalus’ being his first penname, ‘The Outsider’ the second, and ‘Kautilya’ his last. An authoritative and memorably stylish editorialist, he was also a subversively satirical columnist (and occasional versifier).

In a singular honour, in 1971Mervyn de Silva spent a month in DC working with the legendary Foreign Editor of the Washington Post, Phil Foisie, at the end of which a think-piece by Mervyn was given a rare full-page spread in The Washington Post (1971).

He also authored two Editorial page pieces in the International Herald Tribune (1986). In a ‘world scoop’ he broke the story on the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord (1987) in the Financial Times. Prime Minister Premadasa first came to know of the Accord reading Mervyn in the FT in Tokyo.

Published in and broadcast by the elite Western media, he was also a Vice-President of the International Organization of Journalists (IOJ), the vast network of Soviet bloc and Nonaligned journalists, a rare personification of the confluence of two contending currents and traditions in international journalism: Western liberal-democrat and Socialist/Third World.

His passionate adherence to the highest international standards of journalism and editorship saw him removed from his post twice, by two ideologically antipodal Governments—Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s and JR Jayewardene’s.

Having reached the apex in mainstream newspaper journalism, Mervyn founded a progressive magazine, repeating his achievement this time in ‘alternative periodical journalism’ as publisher/ founder-editor of the Lanka Guardian.

Mervyn was referred to in the world press as Sri Lanka’s Hassanein Heikal, Nasser’s friend and legendary editor of Al-Ahram (Cairo), and Sri Lanka’s Nikhil Chakravartty, iconic editor of Mainstream (Delhi).

GAMMA

Gamini Weerakoon

, universally known as Gamma, was Sri Lanka’s greatest wartime editor. Unlikely as it may seem, when I look in long retrospect, there was a flicker of that potential already discernible when I first saw him in the early 1970s.

As Editor, Daily News, and Editor-in-Chief, Lake House, Mervyn de Silva (and wife Lakshmi) hosted two parties annually: one, drinks and dinner for the staffers of the English-language Lake House press and foreign journalists in town; the other, cocktails for the diplomatic corps—the former at the private hall upstairs of the Chinese Lotus Hotel in Colpetty, the latter at the Galle Face Hotel. As precocious only son barely in his teens (and long trousers), I was present at the first event.

Gamma Weerakoon, tall, ginger-bearded, gravelly voiced, was a singularly imposing physical presence in the corner by the open windows, holding court amidst a crowd of journos shaking with laughter. As I edged closer I got what it was all about: Gamma had a non-stop stream of stories, mimicry and punchlines which were as unprintably salacious as they were undeniably hilarious. What remained in the mind—apart from a wicked imitation of an Indian cricket commentary—was the man’s personality. You could never ignore him.

“I learned from the best” Gamma told me at my father’s funeral in 1999, referring to his Editors/bosses. If Mervyn, behind his editorial desk, always in suit-and-tie, jacket slung on his chair-back, the most stylishly attired of Sri Lankan Editors, was a respected boss and remote father figure for journalists, Gamma in his rolled sleeves, always accessible in the newsroom –the ‘shopfloor’ so to speak– was the elder brother figure. His inimitable leadership style as Editor was already incubating.

Mervyn had left mainstream journalism in 1978 and founded the fortnightly Lanka Guardian magazine. A journal was a more conducive vehicle for critical inquiry about the larger Lankan crisis. Making a comeback having been sacked by Sirimavo and JR, founding and sustaining a periodical which immediately had high visibility and impact, made Mervyn a legend once again, but Gamma’s challenge as Editor of a relatively new mainstream newspaper was equally if differently demanding.

Vijitha Yapa, The Island’s first editor was also an outstanding wartime editor but he quit journalism to establish his famous bookstore. Gamma was on the frontlines every day, in the journalistic trenches, giving leadership during decades of civil wars and foreign military intervention.

The task of the editor of a state-run newspaper was simple in wartime. Gamma wasn’t one. He captained a privately-owned paper which had to maintain credibility as it reported the news, took editorial stands, published diverse commentary. A strong man, he was the courageous editor of a combative newspaper which provided an indispensable space for sovereignty and freedom, democracy and order against all comers, during the most massively violent period of our history in a century.

AJITH

Ajith Samaranayake’s

entry into professional journalism was facilitated by the LSSP theoretician Hector Abhayavardhana, but well before he joined Lake House, he had been published in the prestigious editorial page of the Ceylon Daily News by Mervyn de Silva. That first foray in the early 1970s was a perfectly written little piece, the title of which caught the eye of the editor who was always sympathetic to the off-beat, provided it was well-written. Ajith wrote unforgettably on ‘Why I Failed the A-levels Three Times’.

The next time Ajith caught Mervyn’s eye was in 1976, when I had pointed out to him a report at the bottom of the Daily Observer’s front page, on a ‘Sweep-Ticket Seller’. It was a mini-masterpiece of a ‘human interest story’. Mervyn called in Ajith and gave him a regular slot and larger responsibility which opened his pathway eventually to the Editor’s chair of The Island and the Sunday Observer respectively.

Several things distinguished Ajith as a journalist and Editor. He apprenticed with those who belonged to the first post-Independence generation of the intelligentsia and journalism (like Mervyn), but was himself of a younger generation than most of his colleagues, which meant he was socialised, formed, in a different time of The island’s history, had a different vantage-point and brought to bear different perspective.

Born in 1954, Ajith grew up not only in post-1956, but also post-1971 Sri Lanka. Though he had been mentored by highly literate left and liberal minds of an older generation, Ajith filtered that knowledge through the very different collective experience of his tormented generation and let his considerable reading illumine that experience. Ajith’s sensibility was shaped by engagement with the bilingual arts, politics, writings, reflections and personalities of our contemporary history.

He was a bridge that brought the work of the Sinhala-educated intelligentsia, especially the cultural intelligentsia, to the attention of the readers of mainstream English-language newspapers, while he enriched the endogenous intelligentsia by bringing to bear the best of western (including Marxist) literary criticism to the evaluation of their work.

In that sense Ajith was carrying on the pioneering cross-cultural criticism of Charles Abeysekara and Sarath Amunugama.

Ajith Samaranayake was primarily a cultural critic in whose contributions as journalist and Editor, the socio-cultural dimension bulked large.

His superb ‘situating’ of personalities past, made Regi Siriwardena dub him ‘the prince of obituarists’.

One of Ajith’s acts as Editor, The Island was to give the forgotten but influential radical literary critic and lecturer at the University of Kelaniya, Ranjith Gunawardena, a half-page column on writers and criticism, which ran into a series of several dozen articles.

Tragically, an inescapable aspect of journalistic culture universally, proved to be Ajith’s undoing. Mervyn and Gamma introduced him to the bars where he met the journalistic fraternity. A heavy but self-controlled drinker, Mervyn never touched local booze even as a reporter, while Gamma had a boxer or ruggerite’s physique to absorb anything he drank. Ajith, frail, never had the stamina but could never kick the habit. It took him on a downward spiral to the lower depths, once too often.

Features

An opportunity to move from promises to results

The local government elections, long delayed and much anticipated, are shaping up to be a landmark political event. These elections were originally due in 2023, but were postponed by the previous government of President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The government of the day even defied a Supreme Court ruling mandating that elections be held without delay. They may have feared a defeat would erode that government’s already weak legitimacy, with the president having assumed office through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct electoral mandate following the mass protests that forced the previous president and his government to resign. The outcome of the local government elections that are taking place at present will be especially important to the NPP government as it is being accused by its critics of non-delivery of election promises.

Examples cited are failure to bring opposition leaders accused of large scale corruption and impunity to book, failure to bring a halt to corruption in government departments where corruption is known to be deep rooted, failure to find the culprits behind the Easter bombing and failure to repeal draconian laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act. In the former war zones of the north and east, there is also a feeling that the government is dragging its feet on resolving the problem of missing persons, those imprisoned without trial for long periods and return of land taken over by the military. But more recently, a new issue has entered the scene, with the government stating that a total of nearly 6000 acres of land in the northern province will be declared as state land if no claims regarding private ownership are received within three months.

The declaration on land to be taken over in three months is seen as an unsympathetic action by the government with an unrealistic time frame when the land in question has been held for over 30 years under military occupation and to which people had no access. Further the unclaimed land to be designated as “state land” raises questions about the motive of the circular. It has undermined the government’s election campaign in the North and East. High-level visits by the President, Prime Minister, and cabinet ministers to these regions during a local government campaign were unprecedented. This outreach has signalled both political intent and strategic calculation as a win here would confirm the government’s cross-ethnic appeal by offering a credible vision of inclusive development and reconciliation. It also aims to show the international community that Sri Lanka’s unity is not merely imposed from above but affirmed democratically from below.

Economic Incentives

In the North and East, the government faces resistance from Tamil nationalist parties. Many of these parties have taken a hardline position, urging voters not to support the ruling coalition under any circumstances. In some cases, they have gone so far as to encourage tactical voting for rival Tamil parties to block any ruling party gains. These parties argue that the government has failed to deliver on key issues, such as justice for missing persons, return of military-occupied land, release of long-term Tamil prisoners, and protection against Buddhist encroachment on historically Tamil and Muslim lands. They make the point that, while economic development is important, it cannot substitute for genuine political autonomy and self-determination. The failure of the government to resolve a land issue in the north, where a Buddhist temple has been put up on private land has been highlighted as reflecting the government’s deference to majority ethnic sentiment.

The problem for the Tamil political parties is that these same parties are themselves fractured, divided by personal rivalries and an inability to form a united front. They continue to base their appeal on Tamil nationalism, without offering concrete proposals for governance or development. This lack of unity and positive agenda may open the door for the ruling party to present itself as a credible alternative, particularly to younger and economically disenfranchised voters. Generational shifts are also at play. A younger electorate, less interested in the narratives of the past, may be more open to evaluating candidates based on performance, transparency, and opportunity—criteria that favour the ruling party’s approach. Its mayoral candidate for Jaffna is a highly regarded and young university academic with a planning background who has presented a five year plan for the development of Jaffna.

There is also a pragmatic calculation that voters may make, that electing ruling party candidates to local councils could result in greater access to state funds and faster infrastructure development. President Dissanayake has already stated that government support for local bodies will depend on their transparency and efficiency, an implicit suggestion that opposition-led councils may face greater scrutiny and funding delays. The president’s remarks that the government will find it more difficult to pass funds to local government authorities that are under opposition control has been heavily criticized by opposition parties as an unfair election ploy. But it would also cause voters to think twice before voting for the opposition.

Broader Vision

The government’s Marxist-oriented political ideology would tend to see reconciliation in terms of structural equity and economic justice. It will also not be focused on ethno-religious identity which is to be seen in its advocacy for a unified state where all citizens are treated equally. If the government wins in the North and East, it will strengthen its case that its approach to reconciliation grounded in equity rather than ethnicity has received a democratic endorsement. But this will not negate the need to address issues like land restitution and transitional justice issues of dealing with the past violations of human rights and truth-seeking, accountability, and reparations in regard to them. A victory would allow the government to act with greater confidence on these fronts, including possibly holding the long-postponed provincial council elections.

As the government is facing international pressure especially from India but also from the Western countries to hold the long postponed provincial council elections, a government victory at the local government elections may speed up the provincial council elections. The provincial councils were once seen as the pathway to greater autonomy; their restoration could help assuage Tamil concerns, especially if paired with initiating a broader dialogue on power-sharing mechanisms that do not rely solely on the 13th Amendment framework. The government will wish to capitalize on the winning momentum of the present. Past governments have either lacked the will, the legitimacy, or the coordination across government tiers to push through meaningful change.

Obtaining the good will of the international community, especially those countries with which Sri Lanka does a lot of economic trade and obtains aid, India and the EU being prominent amongst these, could make holding the provincial council elections without further delay a political imperative. If the government is successful at those elections as well, it will have control of all three tiers of government which would give it an unprecedented opportunity to use its 2/3 majority in parliament to change the laws and constitution to remake the country and deliver the system change that the people elected it to bring about. A strong performance will reaffirm the government’s mandate and enable it to move from promises to results, which it will need to do soon as mandates need to be worked at to be long lasting.

by Jehan Perera

Features

From Tank 590 to Tech Hub: Reunited Vietnam’s 50-Year Journey

The fall of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City – HCM) on 30 April 1975 marked the end of Vietnam’s decades-long struggle for liberation—first against French colonialism, then U.S. imperialism. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, formed in 1941, fought Japanese occupiers and later defeated France at Dien Bien Phu (1954). The Geneva Accords temporarily split Vietnam, with U.S.-backed South Vietnam blocking reunification elections and reigniting conflict.

The fall of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City – HCM) on 30 April 1975 marked the end of Vietnam’s decades-long struggle for liberation—first against French colonialism, then U.S. imperialism. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, formed in 1941, fought Japanese occupiers and later defeated France at Dien Bien Phu (1954). The Geneva Accords temporarily split Vietnam, with U.S.-backed South Vietnam blocking reunification elections and reigniting conflict.

The National Liberation Front (NLF) led resistance in the South, using guerrilla tactics and civilian support to counter superior U.S. firepower. North Vietnam sustained the fight via the Ho Chi Minh Trail, despite heavy U.S. bombing. The costly 1968 Tet Offensive exposed U.S. vulnerabilities and shifted public opinion.

Of even more import, the Vietnam meat-grinder drained the U.S. military machine of weapons, ammunition and morale. By 1973, relentless resistance forced U.S. withdrawal. In March 1975, the Vietnamese People’s Army started operations in support of the NLF. The U.S.-backed forces collapsed, and by 30 April the Vietnamese forces forced their way into Saigon.

At 11 am, Soviet-made T-54 tank no. 843 of company commander Bui Quang Than rammed into a gatepost of the presidential palace (now Reunification Palace). The company political commissar, Vu Dang Toan, following close behind in his Chinese-made T-59 tank, no. 390, crashed through the gate and up to the palace. It seems fitting that the tanks which made this historic entry came from Vietnam’s principal backers.

Bui Quang Than bounded from his tank and raced onto the palace rooftop to hoist the NLF flag. Meanwhile, Vu Dang Toan escorted the last president of the U.S.-backed regime, Duong Van Minh, to a radio station to announce the surrender of his forces. This surrender meant the liberation not only of Saigon but also of the entire South, the reunification of the country, and a triumph of perseverance—a united, independent nation free from foreign domination after a 10,000-day war.

Celebrations

On 30 April 2025, Vietnam celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of the South and National Reunification. HCM sprouted hundreds of thousands of national flags and red hammer-and-sickle banners, complemented by hoardings embellished with reminders of the occasion – most of them featuring tank 590 crashing the gate.

Thousands of people camped on the streets from the morning of 29 April, hoping to secure good spots to watch the parade. Enthusiasm, especially of young people, expressed itself by the wide use of national flag t-shirts, ao dais (traditional long shirts over trousers), conical hats, and facial stickers. This passion may reflect increasing prosperity in this once impoverished land.

The end of the war found Vietnam one of the poorest countries in the world, with a low per capita income and widespread poverty. Its economy struggled due to a combination of factors, including wartime devastation, a lack of foreign investment and heavy reliance on subsistence agriculture, particularly rice farming, which limited its potential for growth. Western sanctions meant Vietnam relied heavily on the Soviet Union and its socialist allies for foreign trade and assistance.

The Vietnamese government launched Five-Year Plans in agriculture and industry to recover from the war and build a socialist nation. While encouraging family and collective economies, it restrained the capitalist economy. Despite these efforts, the economy remained underdeveloped, dominated by small-scale production, low labour productivity, and a lack of modern technology. Inflexible central planning, inept bureaucratic processes and corruption within the system led to inefficiencies, chronic shortages of goods, and limited economic growth. As a result, Vietnam’s economy faced stagnation and severe hyperinflation.

These mounting challenges prompted the Communist Party of Vietnam to introduce Đổi Mới (Renovation) reforms in 1986. These aimed to transition from a centrally planned economy to a “socialist-oriented market economy” to address inefficiencies and stimulate growth, encouraging private ownership, economic deregulation, and foreign investment.

Transformation

Đổi Mới marked a historic turning point, unleashing rapid growth in agricultural output, industrial expansion, and foreign direct investment. Early reforms shifted agriculture from collective to household-based production, encouraged private enterprise, and attracted foreign investment. In the 2000s, Vietnam became a top exporter of textiles, electronics, and rice, shifting towards high-tech manufacturing (inviting Samsung and Intel factories). By the 2020s, it emerged as a global manufacturing hub, the future focus including the digital economy, green energy, and artificial intelligence.

In less than four decades, Vietnam transformed from a poor, agrarian nation into one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies, though structural reforms are still needed for sustainable development. Growth has remained steady, at 5-8% per year.

Vietnam’s reforms lifted millions out of poverty, created a dynamic export-driven economy, and improved education, healthcare, and infrastructure. This has manifested itself in reducing extreme poverty from 70% to 1%, increasing literacy to 96%, life expectancy from 63 to 74 years, and rural electrification from less than 50% to 99.9%. Industrialisation drove urbanisation, which doubled from 20% in 1986 to 40% now.

This change displayed itself during the celebrations in HCM, amid skyscrapers, highways and the underground metro system. Everybody dressed well, and smartphones could be seen everywhere – penetration has reached three-fourths of the population. Thousands turned out on motorbikes and scooters (including indigenous electric scooters) – two-wheeler ownership is over 70%, the highest rate per capita in ASEAN. Traffic jams of mostly new cars emphasised the growth of the middle class.

At the same time, street food vendors and makeshift pavement bistro owners joined sellers of patriotic hats, flags and other paraphernalia to make a killing from the revellers. This reflects the continuance of the informal sector– currently representing 30% of the economy.

The Vietnamese government channelled tax income from booming sectors into underdeveloped regions, investing in rural infrastructure and social welfare to balance growth and mitigate urban-rural inequality during rapid economic expansion. Nevertheless, this economic transformation came with unequal benefits, exacerbating income inequality and persistent gender gaps in wages and opportunities. Sustaining growth requires tackling corruption, upgrading workforce skills, and balancing development with inequality.

NLF flag

Tank 390 courtesy Bao Hai Duong

The parade itself, meticulously carried out (having been rehearsed over three days), featured cultural pageants and military displays and drew admiration. Of special note, the inclusion of foreign military contingents from China, Laos, and Cambodia for the first time signalled greater regional solidarity, acknowledging their historical support while maintaining a balanced foreign policy approach.

Veteran, war-era foreign journalists noted another interesting fact: the re-emergence of the NLF flag. Comprising red and blue stripes with a central red star, this flag had never been prominent at the ten-year anniversary celebrations. The journalists questioned its sudden reappearance. It may be to give strength to the idea of the victory being one of the South itself, part of a drive to increase unity between North and South.

Before reunification in 1975, North and South Vietnam embodied starkly contrasting economic and social models. The North operated under a centrally planned socialist system, with collectivised farms and state-run industries. It emphasised egalitarianism, mass education, and universal healthcare while actively preserving traditional Vietnamese culture. The South, by contrast, maintained a market-oriented economy heavily reliant on agricultural exports (rice and rubber) and foreign aid. A wealthy elite dominated politics and commerce, while Western—particularly American—cultural influence grew pervasive during the war years.

Following reunification under the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1976), the government moved swiftly to integrate the two regions. In 1978, it introduced a unified national currency (the đồng, VND), merging the North’s and South’s financial systems into a single, state-controlled framework. The unification of monetary policy symbolised the broader ideological project: to erase colonial and capitalist legacies.

Unity and solidarity

However, the economic disparities and cultural divides between regions persist, though less pronounced than before. The South, particularly HCM, remains Vietnam’s economic powerhouse, with a stronger private sector and international trade connections. The North, including Hanoi, has a more government-driven economy. Southerners tend to have a more entrepreneurial mindset, while Northerners are often seen as more traditional and rule-bound. Conversely, individuals from the North occupy more key government positions.

Studies suggest that people in the South exhibit lower trust in the government compared to those in the North. HCM tends to have stronger support for Western countries like the United States, while Hanoi has historically maintained closer ties with China. People in HCM tend to use the old “Saigon” city name.

Consequently, the 50th anniversary celebrations saw a focus on reconciliation and unity, reflecting a shift in perspective towards peace and friendship, as well as accompanying patriotism with international solidarity.

The exuberant crowds, modern infrastructure, and thriving consumer economy showcased the transformative impact of Đổi Mới—yet lingering regional disparities, informal labour challenges, and unequal gains remind the nation that sustained progress demands inclusive reforms. The symbolic return of the NLF flag and the emphasis on unity underscored a nuanced reconciliation between North and South, honouring shared struggle while navigating enduring differences.

As Vietnam strides forward as a rising Asian economy, it balances its socialist legacy with global ambition, forging a path where prosperity and patriotism converge. The anniversary was not just a celebration of the past but a reflection on the complexities of Vietnam’s ongoing evolution.

(Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute. He is a convenor of the Asia Progress Forum, which can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com.)

By Vinod Moonesinghe

Features

Hectic season for Rohitha and Rohan and JAYASRI

The Sri Lanka music scene is certainly a happening place for quite a few of our artistes, based abroad, who are regularly seen in action in our part of the world. And they certainly do a great job, keeping local music lovers entertained.

The Sri Lanka music scene is certainly a happening place for quite a few of our artistes, based abroad, who are regularly seen in action in our part of the world. And they certainly do a great job, keeping local music lovers entertained.

Rohitha and Rohan, the JAYASRI twins, who are based in Vienna, Austria, are in town, doing the needful, and the twosome has turned out to be crowd-pullers.

Says Rohitha: Our season here in Sri Lanka, and summer in the south hemisphere (with JAYASRI) started in October last year, with many shows around the island, and tours to Australia, Japan, Dubai, Doha, the UK, and Canada. We will be staying in the island till end of May and then back to Austria for the summer season in Europe.”

Rohitha mentioned their UK visit as very special.

The JAYASRI twins Rohan and Rohitha

“We were there for the Dayada Charity event, organised by The Sri Lankan Kidney Foundation UK, to help kidney patients in Sri Lanka, along with Yohani, and the band Flashback. It was a ‘sold out’ concert in Leicester.

“When we got back to Sri Lanka, we joined the SL Kidney Foundation to handover the financial and medical help to the Base Hospital Girandurukotte.

“It was, indeed, a great feeling to be a part of this very worthy cause.”

Rohitha and Rohan also did a trip to Canada to join JAYASRI, with the group Marians, for performances in Toronto and Vancouver. Both concerts were ‘sold out’ events.

They were in the Maldives, too, last Saturday (03).

Alpha Blondy:

In action, in

Colombo, on

19th July!

JAYASRI, the full band tour to Lanka, is scheduled to take place later this year, with Rohitha adding “May be ‘Another legendary Rock meets Reggae Concert’….”

The band’s summer schedule also includes dates in Dubai and Europe, in September to Australia and New Zealand, and in October to South Korea and Japan.

Rohitha also enthusiastically referred to reggae legend Alpha Blondy, who is scheduled to perform in Sri Lanka on 19th July at the Air Force grounds in Colombo.

“We opened for this reggae legend at the Austria Reggae Mountain Festival, in Austria. His performance was out of this world and Sri Lankan reggae fans should not miss his show in Colombo.”

Alpha Blondy is among the world’s most popular reggae artistes, with a reggae beat that has a distinctive African cast.

Calling himself an African Rasta, Blondy creates Jah-centred anthems promoting morality, love, peace, and social consciousness.

With a range that moves from sensitivity to rage over injustice, much of Blondy’s music empathises with the impoverished and those on society’s fringe.

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOTRFU Beach Tag Rugby Carnival on 24th May at Port City Colombo

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTrump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai