Features

The story I had to tell

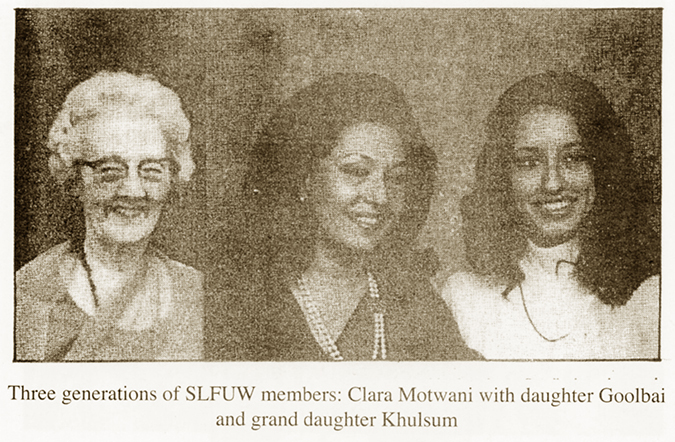

Excerpted from Chosen Ground: The Clara Motwani Saga by Goolbai Gunasekare

“You have a story to tell,” said my friend Shirani Captain one day, when we were idly chatting about our parents and the peculiarities of their era. “Why don’t you write it?” And so began this book.

Shirani had an English mother, and like me, was half Asian. There was, however, no other resemblance in our juvenile backgrounds. Shirani’s days were not encompassed by academics. She led a far more normal life vis-a-vis the norms and customs of the day. Her parents, Mr. L.A. Weerasinghe (former Auditor General of Sri Lanka) and his wife, played golf regularly, and led a very active social life: a luxury denied to my Professor/Principal parents, whose careers occupied all their time.

But we did have one link that held us solidly together in our teenage years. We each had a young male admirer. These two young swains, Bunchy and Sohli, happened to be best friends. Ergo, it was inevitable that their ‘girlfriends’ would team up in efforts to hoodwink parental authority as best they could, and aid each other in all the downright lies that are told in the furtherance of illicit meetings and other clandestine rendezvous (the only way we got to meet anyone not ticked off as approved acquaintances in parental diaries).

Romance bubbled merrily behind our parents’ backs. To have a `boyfriend’, even a ‘friend’ who happened to be a boy, was not to be thought of. When it came to boys, even the most liberal parents drew cords of discipline so tight we never got to breathe the heady air of teenage freedom. We had none. Even my mother, so broadminded in general, tended to share in the common adult suspicion that hung around teenage doings.

Strangely enough my parents were agreed upon that one restriction. Liberal as they were, their liberality did not extend to too much freedom of movement where the opposite sex was concerned. Father brought us up on the Rama/Sita mindset. Not that he approved of the chauvinistic Rama’s conduct, but he totally loved Sita’s gracefully yielding ways. Mrs. Girlie Cooke, my friend Mohini’s mother, endeared herself to Father because of her very traditional Tamil appearance and, he assumed, her gracefully yielding ways. He was quite wrong.

Aunty Girlie’s appearance was most deceptive. Beneath her traditional demeanour, was (for her times) a very forward-thinking and free spirit. Her booming serve at tennis, a game she played in a crisp white cotton sari, had her daughter, Mohini and me running off the court rather than face its power.

It was thanks to her intervention that Father allowed me to attend a dance with friends. It was thanks to her that I was allowed (oh, giddy delight) to become modernized outwardly, and actually wear make up. Once I had gone away to university in Bombay, of course, nothing Father said would have prevented that very modernization he disliked.

My parents were mentally and educationally forward-thinking, but they operated within the rules of the East as far as behaviour went. Obviously they did something right. We were given guidelines as to mature behaviour, and then expected to conduct ourselves accordingly.

One or two of my traditionally reared classmates actually braved the wrath of their parents and eloped with quite unsuitable men. They lived to regret it. But the majority … in particular my classmates and closest friends for the last 55 years, Sunetra, Punyakante, Indrani, Mohini, and Hyacinth had marriages arranged for them when they were still quite young. They lived happily ever after as their parents, and mine, expected them to do.

I was away at university when my close friend, Chereen, the class beauty, married. Hers had been a romantic liaison, but parental approval was gained in spite of the fact that in her case a Roman Catholic was marrying an Anglican (and having to brave initial opposition).

Religion was not something our parents harped upon (and when I say ‘our parents’ I mean Suriya’s, Kumari’s and mine). It mattered little to these three sets of parents if the men we chose to marry were theists, atheists, agnostics or even downright heretics. They believed that intelligence should be brought to bear on the matter of personal religion. In their view, organized religion did more harm than good. They felt it divided people, caused wars and resulted in catastrophic disasters.

Suriya, Kumari and I behaved as our parents expected us to do. We did not confound polite society by choosing unsuitable young men. Our partners were approved by all, and somehow we got the impression that our parents expected no less. Religion was never a problem. Our eclecticism caused us to blend comfortably with everyone although truth to tell, I love going to Church. But it is atmosphere rather than dogma that attracts me there.

While Mother and Father were strict in not allowing too much mixing with the opposite sex, they had no objection to boys visiting us at home. They treated all such visitors with courtesy, but did not show them too much warmth. They certainly did not expect every caller to have a walk up the aisle in mind.

“It’s an excellent thing to have many friends,” Mother would say bracingly.

Nonetheless, a wary eye was kept on any trysts that did not take place in full view of parental eyes. Given Su’s record of littering her pathway with broken hearts, it was with a sigh of relief that her wedding in Delhi to young Captain (later Brigadier) Kailash Kalley was greeted. Kailash is an alumnus of the famous Doone School in Dehra Dun, India, and there was a faint surprise in Mother’s happy acceptance of this ‘good’ marriage.

Fortunately, Father did not live to see Su’s marriage end in divorce. It would have caused him much pain, especially as Su has a lovely daughter whom we promptly nicknamed `Bambi’ because of her lambent, doe-like looks.

One of the great sorrows of Mother’s life was that after Su’s separation, she was not granted access to Bambi. Bambi’s father was very embittered by the divorce, and refused to even send his daughter to spend her vacations with us. Mother wrote many times but they were vain attempts. She never saw Bambi again and although she rarely spoke of the deep hurt it caused, I know she mourned the loss of not knowing her other grandchild.

A journalist who interviewed me once for a Women’s Page article in one of the daily papers asked me if I had never desired a more `ordinary background’. Did I not feel that I had always been ‘different’ from my contemporaries, and did I not mind the difference? Frankly, I never thought of it. Mother and Father were always held in such high esteem that both Su and I were very proud to be introduced as Dr. and Mrs. Motwani’s daughters.

In their wisdom, they trained us to think of ourselves as Sri Lankans. Father even brought me back from my school in Ooty in time to offer Sinhala as a subject for my O-Level examination. This qualification made it possible for me to work for a year at the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (then Radio Ceylon). To get any Government job that Sinhala language pass at the O-Level was vital.

I think that as time went by, both Mother and Father felt so Sri Lankan that they were out of tune with the rest of the world. Tours abroad ceased to hold any charm for either of them, and they became typical, retired Colombo-ites. Mother’s doctor used to ask from rime to time if she ever was depressed. Mother was surprised. “Should I be?” she asked. “Retirement often does that to people,” he would reply.

Mother had a secret weapon against depression. Each night, she told me, she would lie in bed and count her many blessings. One day she wrote them out for me. I have the list with me to this day and I am constantly amazed that this well-known public person savoured the small things in life. One of the blessings that she mentions is that she could have tea with her family every day at 4.30 each evening, during the time that she lived with us. It was a time for leisurely conversation and she treasured it. My husband’s and our daughter’s love for her was high on her list.

When we were growing up, Mother’s photograph would be in the papers on a daily basis — so involved was she in dozens of projects. Nor was her name on these many committees merely window-dressing. She really worked with whatever committee she happened to be heading. Leisure-time relaxation was therefore a blessing.

A few days ago, a father brought his nine-year-old daughter to be enrolled at the Asian International School. I asked him why he had opted for this particular school among so many others.

“Well, your mother was my mother’s Principal,” he said, “and my mother told me that if you were even half as good as she was, you would still be pretty good.”

I knew what he meant. It is a comparison which is often made, and one in which I suffer by contrast. Nor do I expect it to be otherwise.

My wise and wonderful mother was one of a kind. What marvellous Karmic links gave me such special and such unusual parents? How were they able to transform an alien island into home? What arcane secret did they possess, that enabled them to become one with the people of the country they chose to live in?

We were not Sinhalese, Tamil, Muslim or Burgher but we were, as Mother said, ‘proudly Sri Lankan’. When Sir John Kotelawala’s government gave Mother the Distinguished Citizenship award, the Dual Citizenship Act had not been passed. Mother would have had to give up her American citizenship in order to accept the Sri Lankan one. She did it, despite the world telling her she was crazy to do so. She knew she would never live anywhere else other than here, in the lovely island of Sri Lanka — her chosen ground.

When Mother died there was an outpouring of tributes to her, both as a Principal and as an educationist. What was most touching, however, were the personal messages from those who knew her as a friend and not just as a public figure. She died in her sleep in 1989, on my husband’s birthday, the 21st of July. Following her often-voiced wish that large numbers of schoolgirls should not be forced to stand around in the sun at her funeral, she was cremated immediately, very privately, with only her family and close friends present. Mother assumed, rightly, that the schools she had headed would feel it necessary to make a showing if the funeral was public.

My parents were both believers in the laws of Karma and rebirth. In seeking for the right words with which to close this book, I cannot find them in my own mind. Nothing I can say is an adequate tribute to my wonderful Mother. Let me therefore borrow the words of another:

“This day has ended

It is closing upon us even now as the water-lily upon its own tomorrow.

Farewell to you and the youth I spent with you. It was but yesterday we met in a dream.

If, in the twilight of memory we should meet once more, we shall speak again together and you shall sing me a deeper song

And if hands should meet in another dream we shall build another tower in the sky. “

From The Prophet by Khalil Gibran

It is the mark of that rarity, a true teacher, that she can build these ‘towers in the sky’ for her pupils. Mother did this for thousands of grateful young girls – and most importantly, she did it for me.

Features

Where the hell have all devils gone?

‘Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again’

–– The Sound of Silence

A drive through the city of Colombo is far less frazzling around midnight, when most asphalt cowboys (read private bus drivers) are in dreamland, and others move like a breeze, having to mind only an occasional wheeled contraption trying to break the sound barrier or policemen in high-vis jackets with flashing traffic wands.

Driving back home after work, some time ago, at an ungodly hour, as usual, yours truly beheld something that opened the floodgates of nostalgia. A devil was staring at him through the rear windshield of a vehicle. An electrifying sight—indeed!

It was actually a sticker of a colourful, apotropaic devil mask—fascinatingly fanged, adorably goggle-eyed, and so endearingly familiar to southerners who grew up among devils, so to speak.

A little over a year ago, a devil beckoned to the writer similarly on the Southern Expressway while he was on his way to Matara with his family for the traditional New Year, which invariably makes him succumb to the irresistible pull of his southern roots.

Well past the witching hour, tossing and turning in bed, in Matara, the writer found something amiss in an otherwise perfect southern night. There was no rub-a-dub of yak bera (low-country drum). During his childhood, pulsating tom-tom beating at thovil or devil dances in his neighbourhood would lull him to sleep.

On that sleepless night, the writer kept thinking to himself, “Where the hell have all the devils gone?”

Coexistence with devils

We, the southerners, evince a proprietary interest in yakas or devils. They may frighten others, but they are no match for the southern exorcists or kattadiyas, who claim to be capable of taming or even banishing them—for a hefty fee, of course. Devil dances are the events where yakas that possess humans are exorcised; they are humiliated in every conceivable manner before being driven out; no yaka with an iota of self-respect would take such mortification lying down if it was capable of striking back. So, a logical conclusion may be that the devils are scared of the southern kattadiyas!

During the writer’s growing-up years, the township of Matara encompassed only a small urban area, beyond which lay rural backwaters, where humans and yakas had opted for an uneasy coexistence, with the latter often overstepping their limits, warranting the intervention of devil dancers.

The writer, as a child, used to think that beyond the area illuminated by household lights in the neighbourhood, all the starving devils in the country converged for the night, keeping a sharp lookout for the brats who dared venture out after dusk. So, he and his elder brother carefully avoided crossing the border demarcated by garden lights lest they should provoke demonic retaliation or even end up as the dinner of the supposedly evil ones.

Cane that drove out fear of devils

The credit for making the writer and his brother overcome their fear of yakas should go to their mother or her unforgiving cane, to be exact. She was not equal to the task of catching them during daytime, try hard as she might, for their mischief or misbehaviour. So, cases against them were heard in absentia in the daylight hours and sentences were duly passed, and all that remained to be done upon their return home at dusk was to mete out punishment, which was severe.

Those were the pre-Child Protection Authority hotline days, and flight was the only option the hapless brothers were left with. So, a scared duo would show their mother a clean pair of heels each, but, darn it, their sprints would end where the dark territory of the devils began!

With the passage of time, the two brothers would summon the courage to cross the line of control between human territory and that of the yakas, and their mother gradually lost interest in the nightly sprints. Otherwise, she would surely have gone on to clinch an Olympic medal for running, a couple of decades before Susanthika! (In ‘My Family and Other Animals’, Gerry Durrell quotes his elder brother as having said that they can be proud of the way they have brought up their mother!)

Conquering fear: Ultimate test

Making an occasional foray into the devils’ territory at night was one thing, but overcoming the fear of demons once and for all was quite another; the ultimate test of masculinity for teens, in that part of the country, sans proper street lighting at the time, was returning home all alone well past midnight after watching a horror movie at a cinema in the nearby town. There were occasions when the writer had to come back home all alone on bicycle or using shank’s pony, passing two cemeteries with large tombs, which, he thought, had been purpose-built for scaring brats who dared wander after nightfall!

‘The Exorcist’ was a scary flick that made any mid-teen worry about the prospect of having to walk the dark roads that lay between the cinema and his home, after the 9.30 pm show––all alone. The snakelike tongue the possessed girl flicked from time to time almost touched the petrified faces of the writer and his friends occupying the front-row seats. Equally blood-curdling were the films like ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’. Dracula also would unnervingly affright them initially to the extent of making them see, on their way back home at night, the blood-sucking creature’s ghastly visage everywhere like a politician’s grinning mug on election posters defacing wayside walls. But later Dracula became a joke, for he/it overdid bloodletting like the violent characters in Tarantino’s edge-of-the-seat thrillers full of gratuitous gory scenes. Subsequently, horror movies became so funny that Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’ amused the writer instead of giving him heebie-jeebies. (Hitchcock is heard saying in an audio recording in the BBC archives that he intended ‘Psycho’ as a comedy, but people took it for a horror movie, and he kept quiet!)

Witnessing the banishment of devils

Years prior to the late arrival of television in Sri Lanka were characterised by a chronic lack of entertainment, and the yakas were considerate enough to move in to fill that vacuum, from time to time, with demonic possessions, which necessitated all-night devil dances. They were the events that provided the writer, his brother and their friends an up-close look at numerous devils, especially Mahasona and Ririyaka, who were in fact the devil dancers wearing magnificent wooden masks representing the anthropomorphic personifications of different yakas.

Frantic yet spellbinding dancing lasted for hours on end to the accompaniment of hypnotically rhythmic drum beating, which reached a crescendo towards the wee hours. The exorcists would go into deep trances then, muttering gobbledygook, which apparently only they and the southern devils understood.

The disease-causing devils were identified, summoned and banished much to the relief of the possessed and family members. Thovil could be considered kangaroo trials for devils. Those ceremonies were well choreographed and highly entertaining; they included scenes that provided comic relief in the form of dialogues between yakas and devil dancers, who ridiculed the former much to the amusement of the spectators. Obscenities that some tipplers who were sozzled to the gills hurled at the devils from the audience made thovil even more entertaining like stormy parliamentary sessions.

Seeing and surviving real yakas

The writer’s encounters with the real yakas happened in the late 1980s, when the southern parts of the country ran red with youthful blood due to the JVP’s reign of terror and the savage counterterror operations carried out by the then UNP government.

Two macabre scenes are etched in the writer’s memory. One day, while travelling from Matara to Peradeniya in 1988, he counted more than 30 blindfolded, mutilated corpses of youth along the way—about 10 being burnt on the roadside at the Ahangama junction, six under the Panadura bridge and the others at different locations along the Kandy-Colombo road up to the Galaha Junction. (Crowds near heaps of corpses, which bore unmistakable marks of torture, would make buses slow down or even stop.) On that day, the writer boarded a Colombo-bound bus, which left Matara at dawn after the curfews imposed by the government and the JVP were lifted. The clunker stopped at an eatery in the Ahangama town, where there was a heavy military presence, as the bus crew thought that no other restaurant would be open beyond that point.

A little distance away from the eating house, about 10 corpses were in flames on a tyre-pyre on the roadside, and a revolting stench of burning human flesh pervaded the air, but the passengers were tucking into buns, etc., and sipping tea quietly while beholding the gruesome scene. It was a sign of the public being desensitised to the horrors of mindless violence unleashed by the Red, Green and Khaki yakas.

The real devils were the JVP killers and the counterterror operatives who went on killing sprees and ran dungeons like the Eliyakanda torture camp or the K-Point in Matara.

Hell must have been empty at that time, for all the devils were in this country preying on the youth!

Death-dealing JVP sparrow units armed with an assortment of weapons unleashed hell in the South, which was a hotbed of terror and counterterror. The JVP ordered poll boycotts, ca’cannies, work stoppages and protests at gunpoint, and noncompliance as well as dissent was suppressed in the most brutal manner.

Many civilians who dared exercise their franchise in defiance of the southern terrorists’ calls for poll boycotts died violent deaths at the hands of the JVP death squads, some of whose victims were burnt alive. Not to be outdone, the then UNP regime set in motion its Caravan of Death, which left streets strewn with corpses of young men and women.

‘The Mountain of Death’

The writer remembers a piteous sight he witnessed more than 30 years ago in a far-flung part of the Ratnapura District. He was a member of a media team, tasked with reporting on the digging up of a mass grave on the mist-clad summit of picturesque Suriyakanda.

The skeletal remains of over one dozen schoolboys from Embilipitiya abducted, tortured, murdered and buried by the counterterror units deployed by the UNP government were found buried in a deep pit.

The mass grave was located away from the winding main road, and only four-wheel drives could reach it. Nylon boot laces used to truss up the victims were still intact. The exhumation process proved extremely tedious. Dusk was falling with a thick blanket of an unforgiving fog enveloping the mountaintop reducing visibility to near zero. The then Opposition politicians and others engaged in the exhumation of what remained of children’s corpses had to call it a day and return to Colombo.

The media team headed for Suriyakanda again the following morning itself. At several places near Pelmadulla, where they broke the journey, they found rotting corpses removed from nearby cemeteries and dumped on the roadside by pro-UNP thugs as a warning. Worse, cattle bones had been dumped into the partially dug up mass grave on the Suriyakanda summit. However, digging continued without any untoward incident thereafter and parts of more human skeletons were unearthed; all of them were dispatched to the Embilipitiya Court under magisterial supervision and subsequently sent for forensic examination. Some of those who were involved in the mass murder were brought to justice.

Mass displacement of yakas

Much is spoken these days about the displacement of humans and animals like elephants, but that of the southern devils has gone unnoticed! In Matara, urbanisation has led to a sprawling conurbation that encompasses what used to be the countryside, which was home to many yakas.

Urbanisation causes residential areas to shrink and eventually make way for the expansion of commerce. The spread of banlieues and rurban areas has pushed the devils further into the hinterland in the South. Humans’ insatiable greed for land has not spared even cemeteries where some awe-inspiring, old mausolea once stood majestically, intensifying the thrill we, as schoolboys, used to get from horror flicks. This detestable graveyard grab, as it were, however, exemplifies a saying popular among the southerners; roughly rendered into English it means that the people who are scared of devils do not build houses on cemeteries.

Unbridled urbanisation, the advancement of medicine, increasing accessibility to healthcare, and the proliferation of education, which inculcates scientific reasoning and critical thinking in the public, must have caused the mass displacement of yakas. Alas, whatever the reasons, Matara has become much poorer without its demons (not the gun-toting ones)—at least for those who grew up among them.

by Prabath Sahabandu

Features

India-Pakistan standoff likely to continue indefinitely

In a sense India-Pakistan ties have come full circle. Way back in the late forties of the century past these regional heavyweights emerged as two deeply politically polarized states. On the one hand there was India, officially committed to democracy, inclusivism and secularism. On the other, there was Pakistan which championed Islamism in governance and had more of a theocratic bent. Religion has become a defining feature of its national identity.

In a sense India-Pakistan ties have come full circle. Way back in the late forties of the century past these regional heavyweights emerged as two deeply politically polarized states. On the one hand there was India, officially committed to democracy, inclusivism and secularism. On the other, there was Pakistan which championed Islamism in governance and had more of a theocratic bent. Religion has become a defining feature of its national identity.

While the expectation of the advocates of regional peace over the years was that India and Pakistan would make some headway in narrowing their political differences and defuse tensions, this has not come to pass although there have been brief periods when the states met with relative success in normalizing relations. As is known, the differences in respect of political identity between the countries have contributed in some measure to the countries going to war. The partitioning of India in 1947 was an exemplar of these divisive tendencies.

The current hostilities between India-Pakistan, which escalated to grave heights, point to the fact that the South Asian region is very much back in the late forties when war and bloodshed seemed to offer the only means of resolving the countries’ differences.

In the current circumstances, the Indian political leadership had no choice but to take a tough position on Pakistan following the killing of some tourists in Indian-administered Kashmir recently. India cannot afford to be seen as weak. As a dominant regional power it should be seen as attaching priority to its national interest, part of which is the protection of its people.

Yet, provision needs to be made in their bilateral discourse for the conduct of political negotiations to narrow the countries’ differences. For instance, the characterization of the current halt in military operations by India as ‘a pause’ would not help in promoting a sustainable political dialogue. It would not inspire any confidence in Pakistan that an improvement in ties is possible if it gives talks a try.

Besides, the ‘Modi Doctrine’ on terror itself could have a divisive and polarizing impact. Given that ‘terrorism’ is a conundrum of the first magnitude, the possibilities are slim of the sides going to the conference table with optimism and hope that the causes underlying their hostilities could be ironed out in a hurry.

Going forward, it could be best for the countries to avoid the use of polarizing language. After all, no two parties are likely to see eye-to-eye on ‘terror’. But for the purposes of facilitating a dialogue, the excessive spilling of civilian blood by state and non-state actors could be defined as terrorism. From this viewpoint the killing of civilians in Pahalgam in India-administered Kashmir could be defined as terror.

However, the avoidance of polarizing language could prove difficult for India, given the country’s current political and opinion climate. But it would be possible for the states to launch a dialogue for the defusing of tensions based on a step-by-step approach. The space needs to be opened for a peace process that could accumulate gains gradually.

Considering also that the recent incidents have triggered a great deal of nationalist discourse on both sides of the border, delays to launch an India-Pakistan peace dialogue could prove fatal. This is on account of the fact that a hardening of attitudes on both sides of the border could make peace work insurmountably difficult.

However, if a firm foundation is to be laid for a result-oriented bilateral political dialogue, terrorism needs to be condemned and eschewed by both states. India of course is doing this. Pakistan needs to follow suit. From this viewpoint, one would need to agree with Prime Minister Modi that while there could not be wars in the current world order it is also not the time for terror. Negotiations need to take the place of wars and armed combat but all parties to a conflict need to prove their bona fides by condemning terror out of hand.

While much is expected of the principal politicians on both sides of the border, civilian publics in India and Pakistan too need to ensure that peace rather than war dominates bilateral discourse. One does not see a Mahatma Gandhi emerging on the Indian subcontinent in the foreseeable future but peace groups on both sides of the divide need to take centre stage, join hands and work indefatigably towards peace between India and Pakistan.

For far too long in South Asia, nationalistic politicians have been tamely allowed by civil society to dominate public discourse on matters of the first importance for the region. As a result, the South Asian Eight have been prevented from coming together and building bridges of unity among the states concerned. Differences rather than commonalities come to be emphasized and friction rather than concord characterizes regional relations. A case in point is India and Pakistan.

Unfortunately India’s secular and inclusive identity has suffered some erosion over the past few years as a result of nationalistic discourse coming to dominate central government thinking. This seems to have happened to the extent to which India’s secular and inclusive nature has been allowed to be eclipsed by democratic forces. Progressive, democratic opinion in India needs to step in to rectify this imbalance.

Accordingly, the commentator would not be wrong in stating that in their essentials, India-Pakistan relations have come full circle, so to speak. They continue on a largely confrontational course. Much will depend on whether India could re-emphasize its secular, inclusive and pluralistic identity and help in shaping inter-state ties within the region along these parameters.

For their part, dominant political opinion among India’s neighbours should consider it a foreign policy priority to shed their blinkered view of India being a ‘Big Brother’ of some kind and learn to live with it amicably. This should not be viewed as succumbing to Indian domination of any kind but as an essential policy component that serves the enlightened national interest of these neighbours.

Features

Sri Lanka energy crisis: The Future – Part II

Authors: Emeritus Professor I.M. Dharmadasa; Emeritus Professor Lakshman Dissanayake; Emeritus Professor Oliver Ileperuma; Professor Wijendra Bandara; Ms Nilmini Roelens; Mr Saroj Pathirana; Professor Chulananda Gunasekara; Eng. Parakrama Jayasinghe; Dr Keerthi Devendra; Dr Geewananda Gunawardana; Dr Lakmal Fernando; Dr Vidhura Ralapanawa; Dr. Ajith Weerasinghe

(First part of this article appeared yesterday)

7.2 CEB’s resistance to renewable energy

CEB is a government owned organ formed to serve the nation. Citizens of Sri Lanka appreciate and value the work of its staff who work hard to provide an essential service to her people. However, the CEB’s unwillingness to change and ongoing resistance towards renewables was not only disappointing but has now become entirely unacceptable.

Whilst the stated energy policies place renewable energy high on the agenda and certainly, by 2050 Sri Lanka has made international commitments to supplying 100% of its needs via zero carbon energy, and 70% renewable energy by 2030, there has clearly been little or no effort to invest in renewable energy infrastructure.

Had the CEB done so diligently, in compliance with the dictates of international commitments and common sense, no lone macaque nor weather pattern could have caused nationwide power outages. What guarantees that another monkey would not trample a transformer again? It beggars belief that the entire nation should be kept in the dark across three days because of one primate.

8.0 A numbers game

Back in January 2025, the independent power regulator the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka predicted a 44 billion LKR surplus profits7 for the CEB and recommended that a reduction in price be passed on to the consumer. Following initial resistance by the CEB it would appear a public consultation led to some cuts ensuing.

In 2024 public financc reported a quarterly profit of 34.5 billion LKR with a total net profit of 93 billion LKR for the CEB.

“Despite a drop in revenue, the CEB posted a 67 percent profit increase to 34.5 billion LKR for the quarter ending June 2024, largely due to lower financial expenses and costs.”

Despite these profits, a few weeks ago, CEB announced that the unit price for roof top solar pay back schemes would be scrapped altogether or reduced further in what was clearly a move to disincentivise the use of a freely available renewable energy source. See more about this here.

There are just over 100,000 rooftop solar systems in Sri Lanka which belong mainly to private households, funded through their hard-earned income or using a bank loan.

Given there are around 7 million consumers of electricity in the country we do not understand how a mere 100,000 roof-top solar panels could possibly render the entire national grid to be so fragile.

It is disingenuous for a country to commit to Agenda 2030 and make commitments at UN COP meetings on climate change, only for a state organ like the CEB to discourage and seek to extinguish the renewable energy sector.

In July 2024, CEB reduced the solar tariff from Rs 37 per unit to Rs 27 in violation of a cabinet decision which required such reduction to be approved by the regulator PUCSL (Public Utilities Commission). This behaviour suggests that CEB regards itself as being unaccountable even to the PUCSL. The CEB’s latest proposal is to further reduce the pay back to Rs 19, 17 or 15 per unit, depending on the production level or to scrap it altogether.

Incongruously, we understand the CEB continues to seek to import emergency fossil-based power at much higher rates of over Rs. 70 per unit.

Why?

We find no logical explanation offered to paying so heavily for imports of fossil fuels whilst thwarting the renewable energy sector from expanding.

As a part of its Clean Sri Lanka strategy, perhaps it would be pertinent for the new Sri Lankan government to consider not only complying with the COP international commitments to offer clean renewable energy but also to consider if any potential “conflict of interests” exists within the Sri Lankan energy sector.

Similar pay back schemes to Net plus or Net plus plus are available throughout the world as a means of encouraging citizens to take advantage of the move towards Net zero and to promote the universal use of renewable energy as a means of addressing climate change.

The CEB’s concerted efforts to undermine and reverse renewable energy commitments and its own failure to invest in the grid infrastructure to support a move towards a 100% renewable energy goal by 2050 is apparent.

The further unit price reduction on pay back schemes and the recent press releases leaving the country in the dark over vacation periods were all the more perplexing since the Asian Development Bank approved a further loan for $200 million in November 2024 to improve the country’s energy infrastructure: See “ADB has approved a $200 million loan to upgrade Sri Lanka’s power grid, enhance renewable energy integration, reduce power interruptions, and modernize infrastructure.”

Have these funds now been released, and have they yet been applied for the purposes for which this loan was offered by ADB?

We understand ADB funding given to develop the infrastructure for enhanced absorption of distributed renewable energy has largely been used to develop higher capacity HT transmission lines and not the much cheaper distribution sector development of roof top Solar PV. Failure to install 20 MW grid scale batteries targeted by Jan 2024 increasing up to 100 MW by 2026 would be an example of the many issues in CEB’s infrastructure plans.

The World Bank announced on 7 May 2025 its approval of a $1 billion loan to support growth in Sri Lanka of which $185m is to be applied to the energy sector. The agreement is “Supporting new solar and wind generation equivalent to 1 gigawatt of capacity, aimed at lowering electricity costs for families and businesses. The project is expected to mobilize over $800 million in private investment and includes $40 million in guarantees.”

It is also common knowledge from previous Cope committee discussions, that Senior CEB engineers’ salaries were between ~Rs 400,000 and ~900,000 per month, and their income tax was paid by the CEB and not by the individuals themselves. Could this be a violation of the Income Tax regulations? It removes individual responsibility for taxpayers. We understand the organisation has also approved an automatic salary increase of 25% after every three years.

By comparison the current salary of a senior medical doctor is believed to be about Rs 94,000 pcm, and a graduate teachers’ salary is about Rs 54,000 pcm. There appears to be a considerable disparity for essential services.

Whilst we appreciate the hard work of CEB staff, it does beg the question whether more money should be reinvested in the grid infrastructure to better serve the nation than in such lucrative salaries for state employees in the energy sector.

Indeed, the recent press release seeking to temporarily shut down roof top solar and mini-hydro systems appears only to demonstrate the failure of the CEB to meet its own responsibilities in updating the national grid.

· Recommendations for the future of Sri Lanka’s energy

· At present we have a very fragile grid and the CEB should strenuously endeavour to minimize energy leakages and improve the grid by replacing weak transformers and grid lines. Such continuous improvements will enable us to move gradually towards a “Smart Grid” enabling absorption of large amounts of freely available intermittent renewable energies like wind and solar.

· Currently we have ~2050 MW of renewables installed, comparable to hydroelectricity. When solar power is plentiful during daytime, hydro power can be reduced simply by controlling the water flow without any technical difficulties. This is one way of assuring energy storage while balancing the grid energy. In addition, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and pumped water storage plants should be introduced.

· The future energy carrier is green hydrogen (GH) produced by electrolyzing water using both wind and solar. GH can also be converted into ammonia and methanol to produce fertilizer and be applied for other industrial uses, and for thermal energy in industry. Sri Lanka already has the Sobhadanavi LNG plant which is already commissioned but cannot be used for lack of supply of LNG. Renewables can bridge the gap.

· Sri Lankan energy should be produced by a technology mix, including large hydro & mini-hydro systems, biomass, solar, wind and some limited imported fossil fuels which must be phased out. While accelerating renewable energy use, reliance and perpetuation of imported fossil fuel must be gradually reduced.

· Local solar energy companies should install high quality solar energy systems and provide good after-sales services. The SLSEA must introduce adequate consumer protection guidelines and mandate to regulate the Solar PV service providers. PV companies should also collaborate with local electronic departments to manufacture accessories like inverters to create new jobs and reduce the total cost of the systems. As a country reliant mainly on agriculture, solar water pumping and drip irrigation systems should be introduced for enhanced food production.

· The optimal use of renewable energy and the move away from fossil fuels should include the development and encouragement of the use of electric vehicles. Solar powered charging stations could be provided whilst EV are introduced in a phased manner.

· It is important to increase public awareness through government funded campaigns and schools’ programmes. The public must become aware of the risks of using imported and expensive fossil fuel and the benefits of renewables. Individual efforts should be encouraged to gradually reduce the use of fossil fuels and increase renewable energy products to achieve a cleaner environment, health benefits and enhanced standard of living conditions. (Concluded)

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSAITM Graduates Overcome Adversity, Excel Despite Challenges

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDestined to be pope:Brother says Leo XIV always wanted to be a priest

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoDrs. Navaratnam’s consultation fee three rupees NOT Rs. 300

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoASBC Asian U22 and Youth Boxing Championships from Monday

-

Foreign News6 days ago

Foreign News6 days agoMexico sues Google over ‘Gulf of America’ name change

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoChampioning Geckos, Conservation, and Cross-Disciplinary Research in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoDilmah – HSBC future writers festival attracts 150+ entries

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoBloom Hills Holdings wins Gold for Edexcel and Cambridge Education