Life style

The Secret to Saving Asian

Elephants ? Oranges

BY ZINARA RATNAYAKE

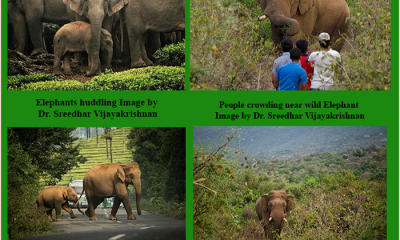

In Sri Lanka, human-elephant conflict has disrupted farmers for generations. In some cases, people are killed. Now, a local conservation organization is looking to citrus as a solution. Bees and fences can’t stop elephants from attacking villages—but orange trees miraculously can.

The November morning was blue-skied and bright. When Wije appeared behind the large orange tree shading his front yard, his eyes crinkled with a broad smile. He wore a rainbow-coloured sarong, a blue face mask, and a Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) T-shirt. This is where he works as a fieldhouse manager. He plucked an orange from a tree to prepare juice. In his village, oranges aren’t just a fruit. They’re a solution to an age-old environmental problem: human-elephant conflict.

Like many villages in the countryside of Sri Lanka, Pussellayaya boasts postcard-worthy landscapes. Wije, short for Aluthgedara Wijerathne, is a 43-year-old native of Pussellayaya, which sits in the southern boundary of Wasgamuwa National Park, about 143 miles from the capital city Colombo in Sri Lanka.

When the charred evening clouds in November bring rain to the village, farmers start sowing the fields of paddy that disappear into a ridgeline of the Knuckles Mountain Range. In the coming months, farmers toil in the fields, but the surrounding wildlife doesn’t make their life easy.

“During the last decade, elephants killed four villagers,” says Wije in his native language Sinhala. “We get very scared at night. Elephants came to destroy our crops and houses. We didn’t have a choice but to retaliate. We lit firecrackers to scare them off, but they became more aggressive, so we fired gunshots into the air, and sometimes at elephants. We didn’t want to harm wild animals, but they were destroying everything we had.”

Growing up in the village, Wije remembers the sleepless nights he spent with his parents. They lit fires and slept on rickety treehouses in the open air in the rice fields, trying to scare off hungry elephants looking for ripe paddy—the only source of income Wije’s parents had.

Orange trees have helped protect Wije’s rice crops while helping him branch out into the world of citrus.

Wije’s story is not different from that of thousands of others living in rural Sri Lanka. The country’s rapidly growing human population and subsequent demand for land result in clearing of natural habitats, squeezing wild animals—like elephants—into smaller pockets of land

The Sri Lankan sub-species of the Asian elephant is already endangered—with as few as 2,500 elephants remaining in Sri Lanka today—but this forces them into shattered jungle habitats. Wild elephants rampage adjacent villages (their original habitat) looking for natural sources of food and water.

A 2010 report by Columbia University’s Earth Institute found that, historically, elephant deaths coincided with reduced rainfall in Sri Lanka’s eastern region. The climate crisis is set to change precipitation patterns in the country and increase the risk of drought. Sri Lanka, which ranked second in the 2019 global climate risk index, already experiences erratic weather patterns.

During Sri Lanka’s dry season, water bodies dry up. Trees wither. Water buffaloes resort to the last remaining mud puddles while searing hot weather cracks the arid soil. In this fetid heat, elephants frequently wander around looking for water, some of them migrating through human habitats where resources exist.

Every year in Sri Lanka, the elephants destroy $10 million worth of crops and property. For the last two years, elephants have killed more than 90 people a year in Sri Lanka. Fearful farmers fight back; in 2019, they killed a record 405 elephants. While human-elephant conflict is a threat to these jungle giants, it also puts impoverished farmers in a vulnerable situation.

“We need to help humans first. If we do that, we can save elephants.”

In the early 1990s, conservationists in Sri Lanka tried to solve the problem by installing electric fences around the villages. But elephants are smart creatures: They began using sticks or branches to break these wires. Busy farmers then have to spend time rebuilding the wires. Ravi Corea, founder of SLWCS, says that farmers who live hand to mouth don’t have the luxury of spending time on such repairs.

Corea understood the need for a long-term solution during his time near Wasgamuwa about three decades ago. After he launched SLWCS in 1995, Corea initiated the project Saving Elephants by Helping People (SEHP) in 1997 to research community-led responses. “I realized that we need to help humans first,” he says. “If we do that, we can save elephants.”

Around 2005, Corea got a surprising tip from the villagers. “Elephants are amazing creatures,” he says, laughing. “They like to remind us that they are the kings in the jungle.”

Elephants often display their power by uprooting trees—but there was one type they left alone: citrus.

So a year later, SLWCS conducted a series of feeding trials with six captive Asian elephants at Dehiwala Zoo, located in suburban Colombo. While elephants gulped down other things such as melons, bananas, paddy, and palm leaves, they tended to eschew oranges and lime fruits and leaves. Their study (which has not been peer-reviewed) concluded that Asian elephants in Sri Lanka have a natural aversion to citrus.

The researchers never found out why elephants didn’t like citrus—they suspect the compound called limonene might be behind it—but those results were promising enough to expand the solution. Corea had already tried other options in between—like beehive fences. They involve fencing the farmer’s crops with beehives. This invention has worked in parts of Africa, but Sri Lankan bees don’t sting as hard as the killer bees of Africa. Moreover, the bees would leave in the dry season in search of water.

By 2011, SLWCS moved forward on the potential citrus solution: It donated orange trees to 12 farmers in Radunna Wewa, another small hamlet in Wasgamuwa. After three years, as the orange plants grew, the farmers saw the difference the plants made. While elephants still stormed through the surrounding main roads, they would take a detour when they smelled citrus. The strong smell of orange now keeps the elephants out of the village, protecting crops and property.

Sixty-year-old Waththegedara Anulawathie is one of Radunna Wewa’s first orange growers. “Elephants don’t come now,” Anulawathie says, her wrinkled face lighting up. Her black and gray hair is loosely braided; her baby pink blouse bright against the backdrop of paddy fields nearby. “Some months, we lost most of our harvest,” she says, pointing to where elephants reduced a house to nothing. “Now we go to sleep at night,” she smiles.

Since their earliest program in Radunna Wewa almost 10 years ago, SLWCS has planted trees in more than 12 villages in the Wasgamuwa region, distributing 25,000 orange plants. Pussellayaya is one of their latest additions. Each of the village’s 300 houses has at least 10 orange trees. In the last five years, SLWCS has estimated that the Wasgamuwa region contributed only about two percent to national human-elephant conflict—including property and crop damage, human deaths, and elephant deaths—according to annual data the organization collects from the region’s Department of Wildlife Conservation.

“Now elephants don’t harm the poor farmers, and farmers don’t harm the elephants,” Corea says, “It’s a win-win for both parties.”

While oranges kept elephants away, their commercial value further incentivized farmers to cultivate the crop. Most traditional paddy farmers struggle to meet their needs, but oranges now provide them an additional income. Farmers grow Bibile sweets, a green orange from Bibile, Sri Lanka, which suits the climate. Anulawathie says a fully grown tree yields about 300 to 500 oranges, which she sells for 15 rupees (about $0.10) each.

However, soaring heat and extreme drought threaten these orchards. In Anulawathie’s garden, two young trees died in August, the driest month of the year. While SLWCS has already developed an irrigation system that brings in water from nearby canals, lakes, and springs, farmers are still struggling.

As more farmers grow Bibile sweets, Corea says they will help protect the natural water springs. Once the trees grow into large orchards, they’ll help shade the bare soil from the harsh sun. Birds, butterflies, and other insects come for orange flowers, too, increasing the area’s biodiversity. “Oranges are addressing the issues of the ecosystem shared by elephants, humans, and other wildlife,” Corea says.

SLWCS relies on volunteers and donations for its projects. While Corea has plans to expand this program, the conservation efforts would require more financial support and intervention from government authorities. Corea and his team had planned to begin feeding trials in Tanzania to African elephants, but the pandemic put that on pause. “We want to see if African elephants show a resistance to citrus as well.”

Now that elephants don’t come to raid their paddy, farmers in Pussellayaya can sleep peacefully. They can reap and sell their harvest in full. Wije, for instance, was able to buy a tuk tuk (auto rickshaw) with last year’s earnings. Wije walks me around the village and shows me a home. The garden is dotted with orange trees, planted only four years ago. In May, the family sold their first harvest.

We walk to the SLWCS field office, and Wije squeezes a few oranges for juice. It’s a great way to kill the scorching heat. Wije peels off the orange rind, but he has already learned that the outer skin is also useful. SLWCS is planning to make essential oil from orange peel, as well as introduce products with a longer shelf life: jam, bottled-juices, and cordials.

Wije believes these products can help bring more income to the villagers. “Until then, we are thankful that elephants don’t come here anymore. Our rice is safe. Our houses are safe. We are safe,” Wije says, smiling. “Elephants are safe, too.”

(BBC)

Life style

Rediscovery of Strobilanthes pentandra after 48 years

A Flower Returns From Silence:

Nearly half a century after it slipped into botanical silence, a ghost flower of Sri Lanka’s misty highlands has returned—quietly, improbably, and beautifully—from the folds of the Knuckles mountain range.

In a discovery that blends patience, intuition and sheer field grit, Strobilanthes pentandra, one of Sri Lanka’s most elusive endemic flowering plants, has been rediscovered after 48 years with no confirmed records of its existence in the wild. For decades, it lived only as a name, a drawing, and a herbarium sheet. Until now.

This rare nelu species was first introduced to science in 1995 by renowned botanist J. R. I. Wood, based solely on a specimen collected in 1978 by Kostermans from the Lebnon Estate area. Remarkably, Wood himself had never seen the plant alive. The scientific illustration that accompanied its description was drawn entirely from dried herbarium material—an act of scholarly faith in a plant already vanishing from memory.

From then on, Strobilanthes pentandra faded into obscurity. For 47 long years, there were no sightings, no photographs, no field notes. By the time Sri Lanka’s 2020 National Red List was compiled, the species had been classified as Critically Endangered, feared by many to be lost, if not extinct.

The turning point came not from a planned expedition, but from curiosity.

In October 2025, Induwara Sachinthana, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Peradeniya with a sharp eye for plants, stumbled upon an unfamiliar flowering shrub while trekking in the Knuckles region.

Sensing its importance, he photographed the plant and sent the images for verification, asking a simple but crucial question: Could this be the recently described Strobilanthes sripadensis, discovered from the Sri Pada sanctuary in 2022?

At first glance, the resemblance was striking. But something didn’t quite add up.

Based on the location, morphology, and subtle floral traits, the initial response was cautious: it was neither S. sripadensis nor S. pentandra—or perhaps something entirely new. Yet, as the pieces slowly aligned, and as the habitat details became clearer, the possibility grew stronger: this long-lost species had quietly persisted in the rugged heart of Knuckles.

The confirmation followed through collaborative expertise. Leading Strobilanthes specialist Dr. Renuka Nilanthi Rajapakse, together with Dr. Himesh Dilruwan Jayasinghe and other researchers, carefully examined the evidence. After detailed comparison with historical descriptions and herbarium material, the verdict was clear and electrifying: this was indeed Strobilanthes pentandra.

What followed was not easy.

A challenging hike through unforgiving terrain led to the first live confirmation of the species in nearly five decades. Fresh specimens were documented and collected, breathing life into what had long been a botanical myth.

Adding further weight to the rediscovery, naturalist Aruna Wijenayaka and others subsequently recorded the same species from several additional locations within the Knuckles landscape.

The full scientific credit for this rediscovery rightfully belongs to Induwara Sachinthana, whose curiosity set the chain in motion, and to the dedicated field teams that followed through with persistence and precision.

Interestingly, the journey also resolved an important taxonomic question. Strobilanthes pentandra bears a strong resemblance to Strobilanthes sripadensis, raising early doubts about whether the Sri Pada species might have been misidentified.

Detailed analysis now confirms they are distinct species, each possessing unique diagnostic characters that separate them from each other—and from all other known nelu species in Sri Lanka. That said, as with all living systems, future taxonomic revisions remain possible. Nature, after all, is never finished telling her story.

Although the research paper is yet to be formally published, the team decided to share the news sooner than planned. With many hikers and locals already encountering the plant in Knuckles, its existence was no longer a secret. Transparency, in this case, serves conservation better than silence.

This rediscovery is more than a scientific milestone. It is a reminder of how much remains unseen in Sri Lanka’s biodiversity hotspots—and how easily such treasures can vanish without notice. It also highlights the power of collaboration across generations, disciplines and institutions.

Researchers thanked the Department of Wildlife Conservation and the Forest Department for granting research permissions, and to the many individuals who supported fieldwork in visible and invisible ways.

After 48 years in the shadows, Strobilanthes pentandra has stepped back into the light—fragile, rare, and reminding us that extinction is not always the final chapter.

Sometimes, nature waits.

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Life style

Desire to connection. understanding sexual health in modern relationships

A conversation about intimacy, belonging and relationships with Dr Yasuni Manikkage

A conversation about intimacy, belonging and relationships with Dr Yasuni Manikkage

In an age where relationships are shaped as much by emotional awareness as by digital connection, conversations about sexual health are finally stepping out of the shadows.

As Dr. Yasuni Manikkage explains, sexual health is not just a medical issue but a lived experience woven through communication, consent, mental wellbeing and self-respect. Many couples share a home, a bed, even children, yet still feel like “Roommates with responsibilities” rather than lovers, which often signal a lack of emotional safety rather than a lack of physical contact. When desire shifts, they may panic, blame themselves or fear the relationship is dying, instead of recognising that changes in desire are common, understandable, and often transformable with knowledge, honest dialogue, and small daily acts of connection.

Q: Why did you decide to talk about sexual desire and connection now?

A: Because so many couples quietly suffer here. They love each other, share a home, raise children, but feel like “roommates with responsibilities” rather than lovers. They rarely talk about sex openly, so when desire changes, they panic, blame themselves, or assume the relationship is dying. I want people to know shifts in desire are common, understandable, and often treatable with knowledge, communication, and small daily changes.

Q: You say there is an “education gap” in sexual health. What do you mean by that?

A: Most women have never been properly taught about their own sexual anatomy, especially where and how they feel pleasure. Many men, on the other hand, have been left to “figure it out” from pornography, jokes, and guesswork. That’s a terrible training manual for real bodies and real emotions. This gap affects how easily women reach orgasm, how safe they feel in bed, and how satisfied both partners feel in the relationship.

Q: We hear about the “orgasm gap.” Is it really not biological?

A: There are biological factors, yes, but the main gap we see between men’s and women’s orgasm rates in heterosexual relationships comes from communication, knowledge, and what I call “pleasure equity.” In many bedrooms, the script is focused on penetration, speed, and the man’s climax. Women’s pleasure is often treated as optional or “extra.” When couples learn anatomy, slow down, focus on both bodies, and talk about what feels good, that gap narrows dramatically.

Q: Most people think desire should be spontaneous. Is that a myth?

A: It’s one of the biggest myths. Movies show desire as a spark that appears out of nowhere: one glance across the room and suddenly you’re tearing each other’s clothes off. That kind of spontaneous desire does happen, especially early in a relationship. But for many people, especially women, desire is often “responsive”. That means they start feeling desire after some warmth, touch, emotional closeness, or stimulation, not before.

So, if you’re waiting to “feel like it” before you touch or connect, you may wait a very long time. For many, desire comes “after” they start, not before.

Q: How would you scientifically describe sexual desire?

A: Desire is not just a physical urge. It’s a blend of attraction to your partner’s body and personality, emotional connection and feeling cared for, a sense of self-expansion or growth, learning, feeling alive with them, trust and safety, both emotionally and physically. It’s contextual: it changes with stress, health, life stages, and relationship quality. It’s relational: it lives between two nervous systems, not just in one body. And for many, it’s responsive: you get in the mood “after” a hug, a joke, a shower together, not randomly at 3 p.m. on a Tuesday.

Q: You mentioned an “updated sexual response cycle.” What does that look like in real life?

A: Older models suggested a straight line: desire, arousal, orgasm and resolution. That’s tidy, but human beings are messy and complex. Modern understanding is more like a circle or loop. You can enter the cycle at different points: maybe you start with touch, or a feeling of closeness, or even just a decision to connect. Desire doesn’t always come first; sometimes it shows up halfway through.

For example, you may feel tired and not “in the mood,” but you agree to cuddle and share some gentle touch. As you relax and feel appreciated, arousal builds, and then desire appears. That’s normal, not fake.

Q: Are there real gender differences in how desire works?

A: There are common patterns, though individuals vary a lot. Many women tend to enter through emotional intimacy: feeling heard, understood, and safe. Physical touch then wakes up arousal, and desire follows.

Many men more often start with physical attraction or arousal. They may feel desire quickly in response to visual or physical cues, and emotional intimacy can deepen later.

Both patterns are healthy and normal. The problem starts when each partner assumes the other should work exactly like them, and if they don’t, they must be “cold” “needy” or “broken.” Understanding these differences turns conflict into curiosity.

Q: How does desire change as a relationship ages?

A: Think of three broad stages.

stage 1 – Early Attraction (0-6 months): High novelty, strong chemistry, lots of dopamine. You’re discovering each other; desire often feels effortless. stage 2 – Deepening Intimacy (6 months-2 years): You know each other better. The high settles. Desire becomes more linked to emotional closeness. Frequency may drop, and that is “normal”.

stage 3 – Maintenance and Maturity (2-10+ years): Life arrives -work, kids, money, health. Desire usually doesn’t feel automatic. It needs conscious attention, novelty, and emotional safety.

A common mistake is comparing stage 3 desire to Stage 1 and assuming, “we’ve failed.” Actually, you’ve just moved into a different phase that requires new skills.

Q: What are some main things that influence desire?

A:We can think in three layers.

Biological: hormones (testosterone, estrogen), brain chemicals (dopamine, serotonin), medical conditions like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic pain, sleep problems, menopause, and genital issues such as vaginal dryness or pelvic floor pain.

Psychological: negative early sexual experiences, trauma or abuse, body image concerns, low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and certain mental health conditions.

Relational and social: how safe and respected you feel, attachment style, quality of communication, power imbalances, work and financial stress, caregiving burdens, privacy, and cultural messages that centre on penetration over pleasure. Desire is never “just in your head” or “just in your hormones” – it’s all three interacting.

Q: What tends to kill desire in long-term relationships?

A: Several patterns show up again and again:

Resentment and unresolved conflict – small hurts that never get repaired.

Lack of emotional safety – fear of being judged, rejected, or punished for being vulnerable.

Poor communication – avoiding difficult topics, sarcasm instead of honesty.

Body image shame – feeling unattractive, “too old,” “too fat,” or “not enough.”

Power imbalance -one partner controlling decisions, money, or sex.

Sexual guilt or religious shame messages that sex is dirty, selfish, or only for reproduction.

Stress, burnout, depression -when your nervous system is in survival mode, it doesn’t prioritise pleasure.

You can’t expect desire to flourish in an environment that feels unsafe, unfair, or constantly tense.

Q: And what actually builds desire?

A: Desire thrives in a combination of safety and aliveness.

Emotional intimacy: feeling seen, heard, and valued.

Nervous system calm: your body is relaxed enough to feel pleasure, not just guard against danger.

Open communication: you can talk about wants, limits, and fantasies without mocking or shutting each other down.

Continued growth: doing new things together, seeing new sides of each other, evolving as a team.

I often say: stagnation is desire’s enemy; growth is its ally. Even small adventures -trying a new cafe, dancing in the living room, travelling a different route-can reawaken curiosity.

Q: Can you give couples a simple framework to reconnect?

A: Yes, I often share a six-step framework that’s practical and gentle.

1. Check in: Ask, “How connected do we feel lately?” Not just “How often are we having sex?”

2. Non-sexual touch: Hugs, stroking hair, holding hands – without expecting sex at the end.

3. Novelty: Try something new together: a class, a walk in a different place, a game, a shared hobby.

4. Appreciation: Tell your partner what you notice and value about them, including non-sexual qualities.

5. vulnerability: Share one fear, one hope, or one truth you usually hide.

6. Initiation: Don’t wait for desire to fall from the sky. Gently invite connection; sometimes the mood follows the movement.

You don’t need to do all of this perfectly. Even one or two steps, done consistently, can shift the energy between you.

Q: How can someone tell if their desire problem needs more attention or professional help?

A: some warning signs include:

You feel emotionally distant, even though you still love each other.

Desire has dropped sharply and is tied to stress, shame, or unspoken conflict.

You feel unable to talk about sex without fighting or shutting down.

sex is used to avoid real intimacy, or to keep the peace, rather than to connect.

You feel afraid or ashamed to say what you truly want-or what you don’t want. In these situations, talking to a doctor, a sexual medicine specialist, or a therapist can be very helpful. You are not “broken” for needing support.

Q: Many couples say, “We love each other but there’s no spark.” What do you tell them?

A: I often say, “Let’s first normalise where you are.” If you’ve been together for years, maybe raising children and navigating financial pressures, it’s normal that your desire doesn’t look like the early days. That doesn’t mean your relationship is dying.

usually, you’re in the maintenance phase. Desire is quieter but can be reawakened with intentional effort: scheduling time for each other, bringing in novelty, and rebuilding emotional safety. It’s less about chasing fireworks and more about tending a fire so it doesn’t go out.

Q: what about couples with mismatched desires – one wants sex often, the other rarely?

A: This is extremely common. The mistake is to frame it as “the pursuer is demanding” and “the less-desiring partner is rejecting.” underneath, there are often two different nervous systems trying to feel safe.

one partner might use physical closeness to feel secure and loved. The other might need emotional safety first before their body can relax into physical intimacy. When couples understand this, they stop seeing each other as enemies and start cooperating: “How can we meet ‘both’ our needs, instead of arguing about who is right?”

Q: Many people, especially women, say sex feels like an obligation. What does that signal to you as a doctor?

A: It’s a red flag – not that the person is broken, but that something important is missing. sex should be about connection, pleasure, and mutual choice. when it becomes a duty, I look for:

Emotional disconnection or resentment.

Fear of conflict or abandonment if they say no.

Lack of felt safety or freedom to express preferences.

The solution is not to “force yourself more.” It is to rebuild emotional safety, renegotiate consent and expectations, and often to have very honest conversations about what feels missing or painful.

Q: If you could leave couples with a few key messages about desire and connection, what would they be?

A: I’d highlight four truths:

Desire and emotional intimacy are deeply connected. When you feel safe, loved, and seen, desire has space to grow.

Desire changes across life and relationship stages. That’s normal, not evidence of failure.

Safety is the foundation. without trust and a calm nervous system, no technique or position will fix desire.

You have agency. Through communication, intentional connection, and sometimes professional help, it is possible to revive and reshape your sexual relationship. If you are reading this and thinking, “This sounds like us,” my invitation is simple: start with one honest conversation. Ask your partner, “Where do you naturally enter the cycle -through emotions, touch, or arousal? What helps you feel desire? What do you need from me to feel safe and wanted?”

Those questions, asked with kindness and curiosity, can quietly change the entire trajectory of a relationship.

Life style

Ramazan spirit comes alive at ‘Marhaba’

At Muslim Ladies College

The spirit of Ramadan came alive at the Muslim Ladies as the much-awaited pre-Ramadan sale “Marabha” organised by MLC PPA unfolded at SLEC the event drew students, parents and old girls to a colourful celebration filled with the aromas of traditional delicacies and the buzz of excitement from the buzzling stalls

Behind the seamless flow and refined presentation were Feroza Muzzamil and Zamani Nazeem. Whose dedication and eye for detail elevated the entire occasion. Their work reflected not only efficiency but a deep understanding of the institution’s values. It was an event, reflected teamwork, vision and a shared commitment to doing things so beautifully. The shoppers were treated to an exquisite selection of Abayas, hijabs and modern fashion essentials, carefully curated to blend contemporary trends with classic elegance. Each stall offered unique piece from intricately embroidered dresses to chic modern designs. The event also highlighted local entrepreneurs a chance to support homegrown talent. Traditional Ramazan goods and refreshment added a delighted touch, making it as much a cultural celebration as a shopping experience.

- Endless deals,endless possibilities

- Goods at reasonable prices

- Zamani and Feroza setting the bar high

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check