Features

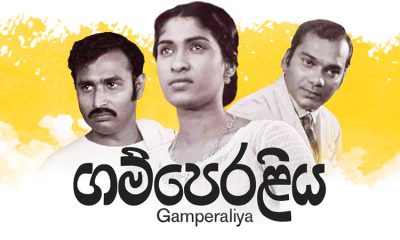

The Popular Sinhala Cinema : Rukmani Devi; Mohideen Baig ; Gamini Fonseka

by Laleen Jayamanne

Rukmani Devi, the first star of the Sinhala cinema and incomparable singer with a unique voice, originally known as Daisy Rasamma Daniel, was a Tamil Christian. It was well known that she couldn’t read or write Sinhala and that her dialogue and lyrics were written in English. Al-Haj Mohideen Baig, who sang some of the most cherished, perennial popular Sinhala film songs (including Budhu Gee), wrote down the Sinhala lyrics in his mother tongue, Urdu. The multilingual Mohideen Baig came to Lanka in 1932 for his brother’s funeral and stayed on. With the guidance of Mohammed Gauss at Columbia records, he began singing on radio soon after. In India he had sung Ghazals in Urdu in his village Salem and also Hindi and Tamil songs.

Once film production began in Lanka, he had a long career as a backup singer, starting with Asokamala (1947). His powerful, textured voice was unique just like Rukmani Devi’s, which made their songs immensely popular. Also, he acted as a beggar in Sujatha (53), walking across landscapes, singing melancholy shoka gee, commenting on the action. His love songs with Rukmani Devi are some of the most heartfelt songs of longing (viraha), in films like Nalagana (1960), which I heard as a child, at the proletarian Gamini theatre Maradana, where their songs blared out vibrating the small theatre and our hearts. Listening to the songs now on YouTube, those memories flood my thoughts (as I write), as only music can, though the films themselves are a faint memory. Gamini was among several Tamil owned cinemas burned down in July 83 race riots.

Here, I wish focus on Rukmani Devi and Baig Master’s careers within the multi-ethnic composition of the Lankan film industry. Gamini Fonseka will make a guest appearance here as a trilingual Sinhala star who built a Tamil fan base. I examine the period from Rukmani Devi’s starring role in the very first Sinhala film Kadawuna Produwa (Broken Promise) in 1947, going beyond her accidental tragic death in 1978, to the murdering of the director K. Vanket in July 83, and concluding with the assassination of the pioneering film producer and entrepreneur, K. Gunaratnam in 1989, by a JVP gunman.

I do this so as to understand anew the cultural value of the early Lankan hybrid popular cinema and its cross-cultural heritage of songs, its multi-ethnic history, through reading and listening carefully to several of its most ardent cinephiles and researchers. They are a group of older, now retired journalists who are in fact the first generation of Sinhala cinephiles and writers of the Lankan cinema, such as A.D. Ranjith Kumara, Sunil Mihindukula former editors of Saraswiya, Ranjan de Silva, Ananda Padmasiri and Ariyasiri Withanage, who have conducted research into those critically maligned early films, their songs and the mass audience and have helped create a film culture through their writing and programming of film songs.

As cinephiles and collectors, their passion for that popular cinema of the past remains undiminished even in retirement. I came across them through a series of informative programmes on Independent Television Network (ITN), directed by Indrasiri Suraweera (available on YouTube). Their careful historical research into the musical traditions of the films, and generosity of spirit should inspire younger generations of critics and intellectuals to do more historical and theoretical work on the Lankan cinema more broadly and not forget its hybrid foundations. It is a cinema I enjoyed as a child, but studied critically while writing my doctorate on female representation in these films. Also, because most of these men were trained as journalists on radio and the print media, they are highly disciplined concise speakers (unlike us verbose academics), so it was a pleasure to listen to them exploring an undervalued period of Lankan mass cultural history. This history has an important relationship to Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism and its relation to the ethnic minorities of the country as well.

A Feminist Perspective on Rukmani Devi’s Career

Rukmani Devi died in a car crash in the early hours of one morning in October 1978. She had been travelling all night from Matara to Negombo, after having sung at a carnival variety show there. While there are numerous accounts of her death in all its detail and of the mass funeral and public mourning recorded on film, there is no discussion of why she was travelling such a long distance all night, from Matara to Negombo, after a ‘hard day’s work…’. As far as I know there is no critical analysis of what happened to her career at midlife and how that might have had some connection to the circumstances leading to that fatal accident. Her career trajectory from super-stardom as both an actress and singer from the 1940s, mingling with political and business leaders and some of the major Indian film stars, appearing on the cover of the Indian film magazine Film Fare, and a long recording and singing career, starting as a girl, from 1938, to end up singing in a variety show down South, is surely an index of the precariousness of her life. Her financial insecurity was also true of the lives of many other people who had worked in the film industry (including technicians, directors, main and supporting actors), in the first decades of Lankan cinema. This dark history should also be included as an essential part of what is often referred to (with pride), by some Sinhala critics as, Sinhala sinamawe wansa kathawa (the illustrious genealogy of the Sinhala cinema).

That Rukmani Devi lived an independent personal life as a professional woman in Lanka, starting quite young as an actress, on stage and film in the late 1940s, strikes me as an important aspect of her career, though the roles available to her on film reinforced feudal patriarchal values. The film Samiya Birindage Deviyaya (The Husband is the Wife’s God, 1963, WMS Tampo), stands as one of the most extreme examples of these oppressive values. It’s been referred to as a ‘women’s picture’, one which ‘they like to watch crying’, said one Sinhala male critic. Hollywood called their version ‘the weepies’, a profitable melodramatic genre targeting the new female spectator-consumer, who attended matinees.

The panellists, Ranjith Kumara has written a book on Rukmani Devi and Ranjan de Silva is a collector of her gramophone records and the song sheets of that era. He is also knowledgeable about Indian musical traditions such as the Raga based Hindustani music and popular Bajan and Ghazal songs for instance. He could hear their precise influences on the best of the early Sinhala film songs and how the originals were adapted and modified, rather than simply copied in the best examples. Appreciating the high quality of the Indian originals, he didn’t simply dismiss the early songs as ‘bad’ just because their origins were ‘Indian’.

His ideas on adaptation are sophisticated and can be used to revise dogmatic views on the early film songs. Most entries on the web simply list Rukmani Devi’s’ films with plot summaries without an analysis of her roles, some even extending her film list to dates well after her death, perhaps their dates of exhibition!

I can find no discussion on how her career ended in sharp decline, and what that means about the economically precarious state of some of the personnel, both men and women in the film industry of that time. There is plenty of adulation and appreciation of Rukmani Devi now as a singer, especially at anniversaries. People still listen to her songs and know her ‘legend’, and sing her songs, but with voices that are very high-pitched and ‘thin’, without her rich timbre nor the wide range of her voice and intensity of feeling. These innate qualities prompted one critic to suggest that she might have been able to sing Western opera as well. There is an unfortunate absence of an account of her as a pioneering female professional actress and singer, the challenges she faced (as a modern high profiled Tamil woman), all of which I think merit research, especially by feminist scholars and critics.

A useful thesis or two may be formulated and written on this and related topics at one of our universities. The existing research by Ranjith Kumara and Ranjan de Silva and younger critics and researchers should be drawn on and extended from a feminist perspective on ‘women and work’ and ‘female representation’ on film. There are a few books written by these older cinephiles, which must be collectors’ items by now. There is a small book by Sarath Ranaweera on Master Baig.

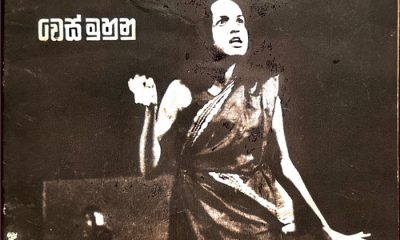

The fact that Rukmani Devi returned to the stage to perform in Dhamma Jargoda’s Vesmuhunu (an adaptation of A street car named desire by Tennessee Williams), either in 69 or 70, was mentioned by Ranjith Kumara, along with a significant anecdote. He said that just before she went on stage to perform as an aristocratic lady (originally Blanche du Bois in Williams’ play), she had insisted on showing her respect to Dhamma in the traditional Sinhala manner of bowing to him by going down on her hands and knees at his feet.

Ranjith Kumara mentions this because, as he rightly says, it was an unusual gesture for a Christian such as Rukmani Devi to perform. Certainly, in our catholic villages, stretching from Uswatakeiyawa to Negombo (Rukmani’s home town with Eddy Jayamanne), there was never such a practice and it still remains quite a foreign gesture to me, though I do appreciate the idea of ‘guru bhakti’ which encodes Rukmani Devi’s gesture. Ranjith Kumara elaborates on this, saying that it was Dhamma’s Shilpiya manasa (artistic intelligence) that Rukmani bowed to. One could take up this fascinating anecdote, told with such perspicacity, a little further.

Cultural Capital: Rukmani Devi and Irangani Serasinghe

I happened to have seen some of the rehearsals of Dhamma’s Vesmuhunu, as an inaugural student of the Art Centre Theatre Studio of 1970/71. If I remember right, Dhamma also did a version of it with Irangani Serasinghe simultaneously, alternating between these two brilliant Lankan actors. Some of us saw both rehearsals in Harrold Peiris’s large open garage at Alfred House, where our workshops were held, before the Lionel Wendt complex was refurbished to house the workshop. So, Rukmani’s unusual gesture of gratitude to Dhamma, I imagine, is because someone of his stature in Lankan theatre had finally given her the gift of playing a serious dramatic role in a modern play. The actress who started her career in the popular Tower Hall Nurti plays of the 40s and the Minerva theatre of B.A.W. Jayamanne, was finally given the opportunity to act in a modern western classic. Kumara also mentioned how much Rukmani Devi appreciated being able to act in Lester James Peries’ Ahasin Polowata (From the Sky to the Earth) where the Nimal Mendis song she sang won her a posthumous award.

There are several other famous global super stars who have yearned recognition and respect as ‘serious’ actors. The most famous of course being Marlin Monroe who produced The Prince and the Showgirl just so she could act with the famous British Shakespearean actor, Lawrence Olivier, while she was still married to Arthur Miller the famous American playwright. For unusually gifted super stars such as these, popularity alone is insufficient, knowing full well how ephemeral, limited and confining their popular ‘sexy’ image is for them, they longed for something more durable to work on, something with cultural and intellectual capital, one might now say.

Perhaps reading Rukmani’s autobiography (Mage Jeevitha Vitti), might provide more leads into the intricate intersections between her life and work, which in her case are especially inseparable, unlike that of any other Lankan film star I know of. Her use of the word ‘vitti’ (information), rather than ‘katha’ (story) suggests that she knew how to protect herself, her privacy. Rukmani Devi’s career started with her elopement and marriage, while still a minor, and she never stopped working in the dominant language which was not her mother tongue, having done only a few performances in Tamil. Whereas, many Lankan Sinhala female stars have left their careers at the height of their popularity to get married and have a family. Most memorably Jeevarani Kurukulasuriya (who formed such a popular romantic duo with Gamini Fonseka, our first male action hero), abandoned her career at marriage.

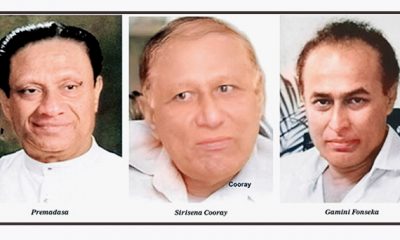

Dharmasena Pathiraja’s comments, at the official celebration held by the then president Maithripala Sirisena (along with the former president Chandrika Bandaranayaka), to mark the 50th anniversary of his professional work in the Lankan film industry, are relevant in thinking about Rukmani Devi’s predicament. He undercut the idea that he had worked ‘professionally’ in the ‘Lankan film industry’. He asked, rhetorically but politely:

“What Industry? How can there be an industry without capital, if there is no professional stability and proper infrastructure? When we look at the sad last days of Rukmani Devi, Domi Jayawardhana and Eddie Jayamanne, how can we speak of an industry? I wasn’t a filmmaker professionally, was anyone able to make a living professionally? I made a living by teaching as a lecturer from 1968-2008. (Maha lokuwata, arambaye sita karmanthayak gana katha keruwath, ape athdakeema anuwa wurthiya sthawarathwayk nathnam kohomada karmanthayak thienne!) The people who say there is an industry are the exhibitors and some producers.”

These starkly realist comments may be taken as an important starting point for future research into the economic, cultural and biographical histories of stars of the Lankan cinema, by young scholars. Clearly, Pathiraja knew from within what exactly had happened to these once very popular actors late in their lives. Perhaps it’s not too late yet to do some oral history before those with personal memory and deep knowledge of the vital early decades also pass away.

I remember visiting Master Hugo Fernando (who did comic routines with his little knot of hair tied at the back and large umbrella tucked under his arm), to talk about the ethos of the old days, which he did so graciously. Kumara and de Silva’s research is indispensable in this regard. Irangani Serasinghe would probably welcome a chance to talk about working with both Dhamma and Rukmani on the same play simultaneously, a most unusual experiment only he could have devised. I feel, in doing so, he was paying homage to two of Lanka’s uniquely popular actors from vastly different social worlds and actorly traditions, with very different cultural capital.

There is a strange symmetry in their career trajectories, but going in opposite directions. Irangani became a beloved house hold name only after the advent of the teledramas once Television was introduced in the late 70s. Prior to that, her acting began at the University Dram Soc where she famously played the heroine in the Greek classic Antigone. After her training at Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, she acted in the English language theatre and in the films of Lester beginning with Rekava (1956). Her repertoire included Shakespeare, Chekov, Lorca, Brecht and others. This also led her to play in Sinhala theatre as well.

During this time, she was recognised as one of our finest actors in both languages, but was not a household name as her work was consistently on the English stage. In contrast, Rukmani was a national figure of great adoration as an actress and singer on film and radio starting from the 40s. While Irangani worked in the domain of high-culture, Rukmani Devi created a Lankan popular mass culture (with Master Baig and others), through her films and songs. But with each change of taste, fashion and the fact of ageing, her film appeal diminished. But her resilience at self-reinvention is evident when she joined the group Los Cabelleros, singing Sinhala pop songs to Latin rhythms, with a show in Jaffna where she sang in Tamil.

I wonder if her Sinhala fans were curious enough to ask her to sing in Tamil as well. In her later years she longed to perform in work that was considered intellectually serious, engaged art. And this chance she did get but belatedly with Dhamma, while Irangani, through her later work in tele-dramas and films, has been able to continue her career well into her 90s and also become a cherished ‘national treasure’. Just as some critics dismissed the early Sinhala films dependent on Indian models, there are those who are critical of many teledramas for their low quality and diluting of popular taste and powers of discrimination. Unlike Irangani’s, Rukmani’s career trajectory marks a sad decline, as Pathiraja stated so forcefully. Therefore, all the massive outpouring of love and grief at her death is no compensation for the loss of worthwhile work. After all she died at only 55 with so much untapped creativity still left.

I am not alone in thinking that Lanka failed this rare artist of national and international stature, as it did Master Mohideen Baig (but more of him later). A visiting Indian star on hearing Rukmani Devi sing had said that, had she been born in India she would have been far more famous. Perhaps like the iconic singer Latha Mangeshkar, of whom Kumar Shahani once said: ‘If India has a heart, then that would be Latha Mangeshkar.’ Singing melancholy songs (Shoka Geetha), but with poetic lyrics written especially for her in Tamil and Sinhala, Rukmani Devi might have become, for all of us, (irrespective of our ethnic differences), Lanka’s sole soulful female voice. Baig Master was the only singer who sang with Mangeshkar, who also sang a song in Sinhala.

Rukmani Devi’s unerring ear meant that she could ‘pass’ as Sinhala, without a trace of her Tamil mother tongue inflecting her enunciation of the words. This ability was not a matter of aesthetics alone within the history of race relations in modern Sri Lanka, then Ceylon. In fact, the ability to pronounce ‘correctly’ the Sinhala word for bucket as ‘baldi’, became a sign of one’s ethnic identity during anti-Tamil riots in July 83. Saying ‘valdi’ instead of ‘baldi’ resulted even in death.

Mohideen Baig, a Muslim, who sang duets with Rukmani Devi, did so with a slight Urdu inflected accent and yet he was an essential part of Sinhala cinema and radio with mass appeal for much of the early period. Together, they evoked a haunting feeling of pathos tinged with a melancholy mood (viraha), in many of their songs, most especially in Jeevana me gamana sansare (samsare of this life’s journey).

Muttusamy and Rocksamy were the leading composers of music for the songs in Sinhala, though there were many other Tamil and Muslim musicians working in the industry as well. Even after better educated writers of lyrics entered the industry these highly skilled musicians continued to compose for them. For example, while Karunaratna Abeysekara wrote the lyrics for Kurul Badda the music was by Muttusamy. Rocksamy composed the music for Dharmasena Pathiraja’s great Tamil language film Ponmani, a truly innovative score in that the main song in the Karnataka idiom is repeated as a refrain, creating an emotional commentary on the main violent action. He also played the saxophone which was banned by the Sinhala nationalists at Radio Ceylon as being a brass Western instrument!

To be continued…

Features

Democracy faces tougher challenges as political Right beefs-up presence

It is becoming increasingly evident that the democracy-authoritarianism division would be a major polarity in international politics going forward. It shouldn’t come as a surprise if quite a few major states of both East and West gain increasing inspiration from the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ under President Donald Trump from now on and flout the core principles of democratic governance with impunity.

It is becoming increasingly evident that the democracy-authoritarianism division would be a major polarity in international politics going forward. It shouldn’t come as a surprise if quite a few major states of both East and West gain increasing inspiration from the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ under President Donald Trump from now on and flout the core principles of democratic governance with impunity.

It is the political Right that would gain most might in this evolving new scheme of things. Whether it be the US itself, France, Israel or Turkey, to name just a few countries in the news, it is plain to see that the Right is unleashing its power with hardly a thought for the harm being done to key democratic institutions and norms.

In fact, Donald Trump and his Republican hard liners led from the front, so to speak, in this process of unleashing the power of the Right in contemporary times. It remains a very vital piece of history that the Right in the US savaged democracy’s most valued institutions on January 6, 2021, when it ran amok with the tacit backing of Trump in the US Capitol.

What was being challenged by the mob most was the ‘will of the people’ which was manifest in the latter’s choice of Joe Biden as US President at the time. To date Trump does not accept that popular verdict and insists that the election in question was a flawed one. He does so in the face of enlightened pronouncements to the contrary.

The US Right’s protégé state, Israel, is well on course to doing grave harm to its democratic institutions, with the country’s judiciary being undermined most. To cite two recent examples to support this viewpoint, the Israeli parliament passed a law to empower the country’s election officials to appoint judges, while Prime Minister Netanyahu has installed the new head of the country’s prime security agency, disregarding in the process a Supreme Court decision to retain the former head.

Such decisions were made by the Netanyahu regime in the face of mounting protests by the people. While nothing new may be said if one takes the view that Israel’s democratic credentials have always left much to be desired, the downgrading of a democratic country’s judiciary is something to be sorely regretted by democratic opinion worldwide. After all, in most states, it is the judiciary that ends up serving the best interests of the people.

Meanwhile in France, the indications are that far Right leader Marine Le Pen would not be backing down in the face of a judicial verdict that pronounces her guilty of corruption that may prevent her from running for President in 2027. She is the most popular politician in France currently and it should not come as a surprise if she rallies further popular support for herself in street protests. Among other things, this will be proof of the growing popular appeal of the political Right. Considering that France has been a foremost democracy, this is not good news for democratic opinion.

However, some heart could be taken from current developments in the Gaza and Turkey where the people are challenging their respective dominant governing forces in street protests largely peacefully. In the Gaza anti-Hamas protests have broken out demanding of the group to step down from power, while in Turkey, President Erdogan’s decades-long iron-fist rule is being challenged by pro-democracy popular forces over the incarceration of his foremost political rival.

Right now, the Turkish state is in the process of quashing this revolt through a show of brute force. Essentially, in both situations the popular demand is for democracy and accountable governance and such aims are generally anathema in the ears of the political Right whose forte is repressive, dictatorial rule.

The onus is on the thriving democracies of the world to ensure that the Right anywhere is prevented from coming to power in the name of the core principles and values of democracy. Right now, it is the European Union that could fit into this role best and democratic opinion is obliged to rally behind the organization. Needless to say, peaceful and democratic methods should be deployed in this historic undertaking.

Although the UN is yet to play an effective role in the current international situation, stepped up efforts by it to speed up democratic development everywhere could yield some dividends. Empowerment of people is the goal to be basically achieved.

Interestingly, the Trump administration could be seen as being in league with the Putin regime in Russia at present. This is on account of the glaringly Right wing direction that the US is taking under Trump. In fact, the global balance of political forces has taken an ironic shift with the hitherto number one democracy collaborating with the Putin regime in the latter’s foreign policy pursuits that possess the potential of plunging Europe into another regional war.

President Trump promised to bring peace to the Ukraine within a day of returning to power but he currently is at risk of cutting a sorry figure on the world stage because Putin is far from collaborating with his plans regarding Ukraine. Putin is promising the US nothing and Ukraine is unlikely to step down from the position it has always held that its sovereignty, which has been harmed by the Putin regime, is not negotiable.

In fact, the China-Russia alliance could witness a firming-up in the days ahead. Speculation is intense that the US is contemplating a military strike on Iran, but it would face strong opposition from China and Russia in the event of such an adventurist course of action. This is on account of the possibility of China and Russia continuing to be firm in their position that Western designs in the Gulf region should be defeated. On the other hand, Iran could be expected to hit back strongly in a military confrontation with the US.

Considering that organizations such as the EU could be expected to be at cross-purposes with the US on the Ukraine and connected questions, the current world situation could not be seen as a replication of the conventional East-West polarity. The East, that is mainly China and Russia, is remaining united but not so the West. The latter has broadly fragmented into a democratic states versus authoritarian states bipolarity which could render the international situation increasingly unstable and volatile.

Features

Chikungunya Fever in Children

Chikungunya fever, a viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes, poses a significant health concern, particularly for children. It has been around in Sri Lanka sporadically, but there are reports of an increasing occurrence of it in more recent times. While often associated with debilitating joint pain in adults, its manifestations in children can present unique challenges. Understanding the nuances of this disease is crucial for effective management and prevention.

Chikungunya fever is caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), an alphavirus transmitted to humans through the bites of infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. These are the same mosquitoes that transmit dengue and Zika viruses, highlighting the overlapping risks in many areas of the world. It is entirely possible for chikungunya and dengue to co-circulate in the same area, leading to co-infections in individuals.

When a mosquito bites a person infected with CHIKV, it ingests the virus. After a period of growth and multiplication of the virus within the mosquito, the virus can be transmitted to another person through subsequent bites. Therefore, the mosquito acts as a vector or an intermediate transmitting agent that spreads the disease, but not as a reservoir of the disease. The spread of chikungunya is influenced by environmental factors that support mosquito breeding, such as stagnant water and warm climates. Urbanization and poor sanitation can exacerbate the problem by creating breeding grounds for these mosquitoes.

The clinical presentation of chikungunya in children can vary, ranging from mild to severe. While some infected children may even be asymptomatic and be normal for all intents and purposes, others can experience a range of symptoms, including a sudden onset of high fever, a common initial symptom. Pain in the joints of the body, while being a hallmark of chikungunya in adults, may be less pronounced in children. However, they can still experience significant discomfort and this must be kept in mind during processes of diagnosis and treatment. It is also important to remember that joint pains can present in various forms, as well as in different locations of the body. There is no characteristic pattern or sites of involvement of joints. Muscle aches and pains can accompany the fever and joint pain as well. A headache, too, could occur at any stage of the disease. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, and fatigue as well.

A reddish elevated rash, referred to in medical jargon as a maculopapular rash, is frequently observed in children, sometimes more so than in adults. While chikungunya is known to cause such a rash, there is a specific characteristic related to nasal discoloration that is worth noting. It is called the “Chik sign” or “Brownie nose” and refers to an increased darkening of the skin, particularly on the nose. This discolouration just appears and is not associated with pain or itching. It can occur during or after the fever, and it can be a helpful clinical sign, especially in areas with limited diagnostic resources. While a generalised rash is a common symptom of chikungunya, a distinctive darkening of the skin on the nose is a particular characteristic that has been observed.

In some rare instances, particularly in infants and very young children, chikungunya can lead to neurological complications, such as involvement of the brain, known as encephalitis. This is associated with a change in the level of alertness, drowsiness, convulsions and weakness of limbs. Equally rarely, some studies indicate that children can experience bleeding tendencies and haemorrhagic manifestations more often than adults.

Diagnosis is typically made through evaluating the patient’s symptoms and medical history, as well as by special blood tests that can detect the presence of CHIKV antibodies (IgM and IgG) or the virus itself through PCR testing.

There is no specific antiviral treatment for chikungunya. Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms and allowing the body to recover on its own. Adequate rest is essential for recovery, and maintaining hydration is crucial, especially in children with fever. Paracetamol in the correct dosage can be used to reduce fever and pain. It is important to avoid aspirin, as it can increase the risk of a further complication known as Reye’s syndrome in children. In severe cases, hospitalisation and supportive care may be necessary.

While most children recover from chikungunya without any major issues, some may experience long-term sequelae. Joint pain can persist for months or even years in some individuals, impacting their quality of life. In rare cases, chikungunya can lead to chronic arthritis. Children that have suffered from neurological complications can have long term effects.

The ultimate outcome or prognosis for chikungunya in children is generally favourable. Most children recover fully within a few days or a couple of weeks. However, the duration and severity of symptoms can vary quite significantly.

Prevention is key to controlling the spread of chikungunya. Mosquito control is of paramount importance. These include eliminating stagnant water sources where mosquitoes breed, using mosquito repellents, wearing long-sleeved clothing and pants, using mosquito nets, especially for young children and installing protective screens on windows and doors. While a chikungunya vaccine is available, its current use is mainly for adults, especially those traveling to at risk areas. More research is being conducted for child vaccinations.

Chikungunya outbreaks can strain healthcare systems and have significant economic consequences. Public health initiatives aimed at mosquito control and disease surveillance are crucial for preventing and managing outbreaks.

Key considerations for children are that some of them, especially infants and young children, are more vulnerable to severe chikungunya complications and early diagnosis and supportive care are essential for minimising the risk of long-term sequelae. Preventing mosquito bites is the most effective way to protect children from chikungunya. By understanding the causation, clinical features, treatment, and prevention of chikungunya, parents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals can work together to protect children from this illness that could sometimes be quite debilitating.

Dr B. J. C. Perera

Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health and Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Founder President, Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians – 1996-97)

Features

The Great and Little Traditions and Sri Lankan Historiography

Power, Culture, and Historical Memory:

(Continued from yesterday)

Newton Gunasinghe, a pioneering Sri Lankan sociologist and Marxist scholar, made significant contributions to the study of culture and class in Sri Lanka by incorporating the concepts of great and little traditions within an innovative Marxist framework. His theoretical synthesis offered historians a fresh perspective for evaluating the diversity of past narratives.

At the same time, Michel Foucault’s philosophical intervention significantly influenced the study of historical knowledge. In particular, two of his key concepts have had a profound impact on the discipline of history:

1. The relationship between knowledge and power – Knowledge is not merely an objective truth but a manifestation of the power structures of its time.

2. The necessity of considering the ‘other’ in any conceptual construction – Every idea or framework takes shape in relation to its opposite, highlighting the duality inherent in all intellectual constructs.

These concepts challenged historians to rethink their approaches, prompting them to explore the dynamic interplay between knowledge, power, and culture. The existence of Little Tradition prompted historians to pay attention to ‘other’ histories.

The resurgence of ethnic identities and conflicts has brought renewed attention to the dichotomy of culture, steering the discourse in a new direction. The ethnic resurgence raises three key issues. First, the way non-dominant cultures interpret the past often differs from the narratives produced by dominant cultures, prompting the question: What is historical truth? Second, it underscores the importance of studying the histories of cultural identities through their own perspectives. Finally, and most importantly, it invites reflection on the relationship between ‘Little Traditions’ and the ‘Great Tradition’—how do these ‘other’ histories connect to broader historical narratives?

When the heuristic construct of the cultural dichotomy is applied to historical inquiry, its analytical scope expands far beyond the boundaries of social anthropology. In turn, it broadens the horizons of historical research, producing three main effects:

1. It introduces a new dimension to historical inquiry by bringing marginalised histories to the forefront. In doing so, it directs the attention of professional historians to areas that have traditionally remained outside their scope.

2. It encourages historians to seek new categories of historical sources and adopt more innovative approaches to classifying historical evidence.

3. It compels historians to examine the margins in order to gain a deeper understanding of the center.

The rise of a new theoretical school known as Subaltern Studies in the 1980s provided a significant impetus to the study of history from the perspective of marginalised and oppressed groups—those who have traditionally been excluded from dominant historical narratives and are not linked to power and authority. This movement sought to challenge the Eurocentric and elitist frameworks that had long shaped the study of history, particularly in the context of colonial and postcolonial societies. The writings of historians such as Ranajit Guha and Eric Stokes played a pioneering role in opening up this intellectual path. Guha, in particular, critiqued the way history had been written from the perspective of elites—whether colonial rulers or indigenous upper classes—arguing that such narratives ignored the agency and voices of subaltern groups, such as peasants, laborers, and tribal communities.

Building upon this foundation, several postcolonial scholars further developed the critical examination of power, knowledge, and representation. In her seminal essay Can the Subaltern Speak?, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak questioned whether marginalized voices—especially those of subaltern women—could truly be represented within dominant intellectual and cultural frameworks, or whether they were inevitably silenced by hegemonic. Another major theorist in this field, Homi Bhabha, also focused on the relationship between knowledge and social power relations. His analysis of identity formation under colonialism revealed the complexities of power dynamics and how they persist in postcolonial societies.

Together, these scholars significantly reshaped historical and cultural studies by emphasising the voices and experiences of those previously ignored in dominant narratives. Their work continues to influence contemporary debates on history, identity, and the politics of knowledge production.

The Sri Lankan historiography from very beginning consists of two distinct yet interrelated traditions: the Great Tradition and the Little Traditions. These traditions reflect different perspectives, sources, and modes of historical transmission that have influenced the way Sri Lanka’s past has been recorded and understood. The Great Tradition refers to the formal, written historiography primarily associated with elite, religious, and state-sponsored chronicles. The origins of the Great Tradition of historiography directly linked to the introduction of Buddhism to the island by a mission sent by Emperor Asoka of the Maurya dynasty of India in the third century B.C. The most significant sources in this tradition include the Mahāvaṃsa, Dīpavaṃsa, Cūḷavaṃsa, and other Buddhist chronicles that were written in Pali and Sanskrit. These works, often compiled by Buddhist monks, emphasise the island’s connection to Buddhism, the role of kingship, and the concept of Sri Lanka as a sacred land linked to the Buddha’s teachings. The Great Tradition was influenced by royal patronage and aimed to legitimise rulers by presenting them as protectors of Buddhism and the Sinhala people.

In contrast, the Little Tradition represents oral histories, folk narratives, and local accounts that were passed down through generations in vernacular languages such as Sinhala and Tamil. These traditions include village folklore, ballads, temple stories, and regional histories that were not necessarily written down but played a crucial role in shaping collective memory. While the Great Tradition often portrays a centralised, Sinhala-Buddhist perspective, the Little Tradition captures the diverse experiences of various communities, including Tamils, Muslims.

What about the history of those who are either unrepresented or only marginally represented in the Great Tradition? They, too, have their own interpretations of the past, independent of dominant narratives. Migration from the four corners of the world did not cease after the 3rd century BC—so what about the cultural traditions that emerged from these movements? Can we reduce these collective memories solely to the Sokari Nadagams?

The Great Traditions often celebrate the history of the ruling or majority ethnic group. However, Little Traditions play a crucial role in preserving the historical memory and distinct identities of marginalised communities, such as the Vedda and Rodiya peoples. Beyond caste history, Little Traditions also reflect the provincial histories and historical memories of peripheral communities. Examples include the Wanni Rajawaliya and the Kurunegala Visthraya. The historical narratives presented in these sources do not always align with those of the Great Tradition.

The growth of caste histories is a key example of Little Historical Traditions. Jana Wansaya remains an important source in this context. After the 12th century, many non-Goigama castes in Sri Lanka preserved their own oral historical traditions, which were later documented in written form. These caste-based histories are significant because they provide a localised, community-centered perspective on historical developments. Unlike the dominant narratives found in the Great Tradition, they capture the social, economic, and cultural transformations experienced by different caste groups. For instance, the Karava, Salagama, and Durava castes have distinct historical narratives that have been passed down through generations.

Ananda S. Kulasuriya traced this historical tradition back to the formal establishment of Buddhism, noting that it continued even after the decline of the Polonnaruwa Kingdom. He identified these records as “minor chronicles” and classified them into three categories: histories of the Sangha and Sasana, religious writings of historical interest, and secular historical works. According to him, the first category includes the Pujavaliya, the Katikavatas, the Nikaya Sangrahaya, and the Sangha Sarana. The second category comprises the Thupavamsa, Bodhi Vamsa, Anagatha Vamsa, Dalada Sirita, and Dhatu Vamsa, along with the two Sinhalese versions of the Pali Hatthavanagalla Vihara Vamsa, namely the Ehu Attanagalu Vamsa and the Saddharma Ratnakaraya. The third category consists of works that focus more on secular events than religious developments, primarily the Rajavaliya. Additionally, this category includes the Raja Ratnakaraya and several minor works such as the Sulu Rajavaliya, Vanni Rajavaliya, Alakesvara Yuddhaya, Sri Lanka Kadaim Pota, Kurunegala Vistaraya, Buddharajavaliya, Bamba Uppattiya, Sulu Pujavaliya, Matale Kadaim Pota, Kula Nitiya, and Janavamsaya (Kulasuriya, 1978:5). Except for a few mentioned in the third category, all other works are products of the Great Historical tradition.

Over the last few decades, Gananath Obeyesekera has traversed the four corners of Sri Lanka, recovering works of the Little Historical Traditions and making them accessible for historical inquiry, offering a new lens through which to reread Sri Lankan history. Obeyesekera’s efforts to recover the Little Historical Traditions remind us that history is never monolithic; rather, it is a contested space where power, culture, and memory continuously shape our understanding of the past. By bringing the Little Historical Traditions into the fold of Sri Lankan historiography, Obeyesekera challenges us to move beyond dominant narratives and embrace a more pluralistic understanding of the past. The recovery of these traditions is not just an act of historical inquiry but a reminder that power shapes what we remember—and what we forget. Sri Lankan history, like all histories, is a dialogue between great and little traditions and it is to engage both of them. His latest work, The Doomed King: A Requiem for Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe, is a true testament to his re-reading of Sri Lankan history.

BY GAMINI KEERAWELLA

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMore parliamentary giants I was privileged to know