Features

“The Flyer With a Big Heart”

Remembering Thibba –

by Nilakshan Perera

My acquaintance with Thibba goes back to March 1979, when I was being inducted as a prefect. As prefects, we had to report to the college and be at the duty points by 6.55am. So I used to travel on the Moratuwa bus instead of my usual 100 Panadura school bus which usually arrived at college by 7.05am, where I met Thibba from opposite Airport Ratmalana, where he was residing down Airport Road. We used to occupy the long seat at the rear of the bus which was shared by the most “mischievous students” on the bus. This friendship blossomed with our shared interests in Cadetting, Cricket, Table tennis, and Swimming. Though Thibba was senior to me by one year we became good friends. After leaving college this great friendship strengthened even further. While Thibba joined the Airforce as an Officer Cadet I had the good fortune to be selected as an Officer Cadet at the Kotelawela Defence Academy (KDA). It so happened that Thibba, TTK Seneviratne, and Ruwan Punchihetti were stationed with us in our final year at the Cadet Wing of KDA in 1985, while doing their flying training attached to Ratmalana Airport which was adjoining KDA. As young cadets we shared many memorable adventures laced with strenuous training, partying, visiting friends, and sometimes playing truant.

28th Oct 1985 one of Thibba’s close friends and batchmate Harshan Jayasinghe ( retired as Squadron Leader in Dec 1996, presently residing in Perth Western Australia, Harshan is an experience banker cum lawyer) disclosed to Thibba from Batticolo where he was the OC of SLAF Batticaloa detachment, one of our schoolmates who played in the pivotal position of the full-back for many years in the Ananda Rugby team, SI Athula Perera (fondly known as Sudu Athula) died during a terrorist landmine explosion at Vellavali in Kalawanchikudy. Thibba suggested we pay our last respects and asked me to be ready by 2300hrs and came to pick me on a motorcycle. It was a blue color Honda CD 200 Roadmaster which he had borrowed from a friend of his down Borupone Road. On our way to the funeral house at Maharagama, Thibba asked me to ride as I love riding and especially this CD 200 as it gives a nice beat. When we were there at the funeral house I noticed that late Athula’s IP insignias were placed wrongly, so I rearranged it correctly. Then Thibba said, “You got a good eye for detail Machan, so please do the same at my funeral as well, and check that everything is in its correct place, if I die during the war”. I never realized nor believed it would happen nor the gravity of it. We spent a few hours there and came back via Bellanwila, not forgetting to have a good load of Koththu and Egg Hoppers from a Ra Kade at Bellaththara.

On our last day at KDA in Nov 1985, Thibba exchanged his photograph with me as this was a custom at KDA. TTK and Ruwan Punchihetti too did likewise and this was an emotional time for all of us( I still have those). During this period the War had escalated and we were all well aware we were facing uncertain times. Each of us embarked on our journeys chartering our destinies.

I well remember my last meeting with Thibba and that day is vividly etched in my memory. It was on 11th Sept 1995 at Maj Jagath Rambukpotha’s ( retired as Major General on 7th July 2016 as Chief of Staff of the Office of Chief of Defence Staff, General with an abundance of military knowledge. A professional Gunnery Officer, who initiated and put in place many new ventures in the SL Artillery and who wears a pleasant smile always) wedding at Grand Orient Hotel. At our table, either side of me was Thibba, and my Course Officer, Lt Col Jayavi Fernando (An architect of Motive and Fighting skills of Special Forces, led troops from the front in many Special Forces battles and shared the pain. Lethal but human great officer lives in the hearts of as highly respected by his subordinates. Retired as Colonel on 31st Oct 1998 as Brigade Commander of Elite Special Forces ) we were reminiscing of our good old days and all those stories were related by Thibba to my wife Rasadari with great humor and laughter, as Thibba was a great storyteller with a lot of humor and light-heartedness.

I well remember my last meeting with Thibba and that day is vividly etched in my memory. It was on 11th Sept 1995 at Maj Jagath Rambukpotha’s ( retired as Major General on 7th July 2016 as Chief of Staff of the Office of Chief of Defence Staff, General with an abundance of military knowledge. A professional Gunnery Officer, who initiated and put in place many new ventures in the SL Artillery and who wears a pleasant smile always) wedding at Grand Orient Hotel. At our table, either side of me was Thibba, and my Course Officer, Lt Col Jayavi Fernando (An architect of Motive and Fighting skills of Special Forces, led troops from the front in many Special Forces battles and shared the pain. Lethal but human great officer lives in the hearts of as highly respected by his subordinates. Retired as Colonel on 31st Oct 1998 as Brigade Commander of Elite Special Forces ) we were reminiscing of our good old days and all those stories were related by Thibba to my wife Rasadari with great humor and laughter, as Thibba was a great storyteller with a lot of humor and light-heartedness.

Thejananda Jayanthalal Chandrasiri Bandara Thibbotumunuwe was born on 8th Nov 1961 to Mr. Ukkubanda Thibbotumunuwe ( A Locomotive Engineer) & Mrs. Somawathi Manike Thiibbotumunuwe (Housewife). He was the 7th child of their family of 9 children. Growing up in a large family may have had a very positive influence on him, as while at school and later on as an Officer in the Sri Lanka Air Force he had proved himself to be an absolute “Team Man” and had always put others before self. This supreme quality of his was displayed to the very end of his life. Like his father and older brother he too had his entire education at Ananda. While in school he was affectionately known as Thibba and even after leaving college this name stuck to him so much so that even after joining the Air Force he would be referred to as Squadron Leader Thibba or even as “Thibba Sir” to some of his juniors.

Even while at school, Thibba’s only ambition was to become a Flyer in the Air Force. His elder brother was an officer attached to Regiment of Artillery ( Maj Gen HB Thibbotumunuwe, retired on 08th Dec 2004, as Quarter Master General) and this too may have inspired Thibba (Jr) to aspire to join the Air Force. While at school Thibba was a keen sportsman. He was a great swimmer having represented the college at the highest level, member of the Under 17 Cricket Team which became All Island Runners up in 1979 under Lasitha Cumarathunge’s Captaincy. Senior Cadet in 1981 which Udeni Jayathillake led the Platoon, and he was also a keen Table Tennis player at college.

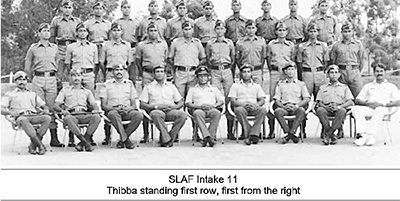

One day Thibba took a News Paper advertisement to his swimming teammate Lasitha Devendra. ( Known as Deva to his batchmates, left the SLAF and presently serves as an IT Consultant, also as a senior IT lecturer in leading state Universities, former Dean of Faculty of Information Technology at Aquinas ) On the same day, they both applied for the Cadetships of SLAF. After successful preliminary interviews, they both with 20 others were finally enlisted to the 11th Intake of Sri Lanka Air Force as Officer Cadets on 18th April 1983. There were 4 from Ananda, Thibba, Razali Noordeen, Lasitha Devendra, and Ushan Wickramasinghe, 3 from Royal, Harshan Jayasinghe, Buwaneka Abeysuriya, Kumar Kiridena, 2 from Nalanda, Chandana Welkala, Mahesh Jayasuriya, 2 from St Thomes’s Mt Lavina, Arulampalam & Kolitha Sri Nissanka, Prashan de Mel from Prince of Wales, TTK Seneviratne from Trinity, Indika Fernando from Joseph Vas Wennappuwa, Harsha Fernando from St Peter’s, Senerath Dissanayake from Gampola Central, Firshan Hassim from DS Senanayake, Rohintha Fernando from St Joseph’s, Suresh Nicholus from Maris Stella Negombo, Asitha Kodithuwakku from St Anthony’s Kandy, Sanjaka Wijemanne from St Anne’s Kurunegala, and Rohan Corea from St Anthony’s Wattala.

They were directly sent to Diyatalawa for Basic Military Training. His batch mates got to know the real Thibba during this physically enduring training programs. His patience, comradeship, dedication to supporting others under extreme conditions was par excellence. One can identify their true self only under very hard times during training. Tibba was a great team player. After exhaustive training days, Tibba was used to sleeping the entire night in a seated position and refused to use his arranged bed prepared for the next day’s morning inspections. He always encouraged, supported all his batch mates, and was probably the friendliest colleague to all. After completing the basic course, they were sent to ChinaBay, Trincomalee for their branch specialization training. Thibba was selected to be a pilot with TTK Seneviratne, while 5 joined Technical Engineering Branch and 15 joined Admin / Regiment Branch.

After being Commissioned as a Flyer Thibba was fully engaged in the flight operations of the Transport Squadron. He was very well conversant as a Captain of Y-8, Y-12, AN 32, and AVRO aircrafts used for air transportation of Troops and Logistics of the Three Services. Under normal situations, SLAF Base Ratmalana was the main airfield used for operating transport flights to Palaly, China Bay. Batticoloa, Vavuniya, etc. However when the ongoing war intensified SLAF decided to use SLAF Base Anuradhapura as the Central Airfield so that it could increase the number of sorties done per day as a result of this reduced flight time, enabling better utilization of available resources. During this period Thibba as well as other flyers were starting flights early in the morning and continuing till late at night. Their selfless, dedicated, and unconditional services were unmatched and greatly admired and appreciated by everyone in our Tri Forces. Thibba was a very familiar figure to everyone who sought Air passage for their leave or getting back to service.

In mid-1990 the LTTE suddenly started attacking military camps in the East. At that time SLAF had only Italian made SIAI-Marchetti SF 260TP as ground-attack aircraft powered by a single Allison 250 Turboprop engine which could carry only 2 X 100Kg bombs as external loads. The entire fleet was fully deployed for air to ground attacks. These aircraft were stationed at Hingurakkoda, even though it was not a Base Camp then. At that time SLAF was short of qualified pilots for SIAI-Marchetti aircraft. As such few pilots including Thibba, Harsha Abeywickrama (a former Commander of the SLAF in 2012-14 and retired as Air Chief Marshel) RP Parkiyanathan ( Wing Commander died, on 13th Sept 1995 Aircraft crash), Bandu Kumbalathara ( retired as Wing Commander in 1999) who were flying transport flights volunteered to fly SIAI- Marchetti Aircraft. Once Thibba had been on a mission to destroy LTTE targets and after accomplishing it returned to base. Soon after he touched the runway the engine had stalled. The Engineering Officer in charge of the fleet, Flight Lieutenant Ruwan Upul Perera (retired in 2005 as Wing Commander) had got the ground crew to tow the aircraft to the Parking Apron. Subsequent checks revealed that the engine stopped due to fuel starvation as Thibba had used maximum fuel that was available to accomplish the mission to the best of his ability, Thibba was solucky that day that he could make a safe landing. If his mission got delayed by another few seconds he would have been in great danger.

In mid-1990 the LTTE suddenly started attacking military camps in the East. At that time SLAF had only Italian made SIAI-Marchetti SF 260TP as ground-attack aircraft powered by a single Allison 250 Turboprop engine which could carry only 2 X 100Kg bombs as external loads. The entire fleet was fully deployed for air to ground attacks. These aircraft were stationed at Hingurakkoda, even though it was not a Base Camp then. At that time SLAF was short of qualified pilots for SIAI-Marchetti aircraft. As such few pilots including Thibba, Harsha Abeywickrama (a former Commander of the SLAF in 2012-14 and retired as Air Chief Marshel) RP Parkiyanathan ( Wing Commander died, on 13th Sept 1995 Aircraft crash), Bandu Kumbalathara ( retired as Wing Commander in 1999) who were flying transport flights volunteered to fly SIAI- Marchetti Aircraft. Once Thibba had been on a mission to destroy LTTE targets and after accomplishing it returned to base. Soon after he touched the runway the engine had stalled. The Engineering Officer in charge of the fleet, Flight Lieutenant Ruwan Upul Perera (retired in 2005 as Wing Commander) had got the ground crew to tow the aircraft to the Parking Apron. Subsequent checks revealed that the engine stopped due to fuel starvation as Thibba had used maximum fuel that was available to accomplish the mission to the best of his ability, Thibba was solucky that day that he could make a safe landing. If his mission got delayed by another few seconds he would have been in great danger.

Another incident was when Thibba was flying from Palali to Ratmalana with 120 soldiers on board coming on leave. When he was about to land he observed on the control panel that the wheels were not coming out for landing. Now his only option was to attempt a crash-landing without the wheels. To minimize the risk of a fire and even a possible explosion Thibba decided to empty the fuel tank by flying a few rounds above the sea and do a belly landing at Ratmalana. While he was flying around the Airport, a higher rank army officer who was on board had asked, “Aren’t we landing?” Thibba answered quietly and calmly that there was a problem with the landing gear and that he was trying to empty the fuel tank so that the risk of fire will be minimized while landing. After listening to this, everyone was most anxious and extremely worried. By now the airport control tower was informed and all firefighters and other emergency procedures were ready on either side of the runway. When he approached the runway to crash-land, Air Traffic Control had informed that the wheels had come out to do a normal safe landing. It turned out that it was only a faulty indicator on the control panel. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when they heard that they can safely land. While everyone on board was anxious and even panicked, Thibba had been as cool as a cucumber even in the face of death. That speaks volumes for the great temperament of this gallant flyer. Thibba was a very skillful and adventurous pilot.

When Palali was under siege in the early 1990s and an Aircraft could not land, Thibba innovated new landing techniques, which surprised the SLAF top-brass, and continued to deliver rations and military hardware to troops stationed in the North. Once, at an airshow in China, Thibba piloted a Y-12 Chinese-made aircraft, and the maneuvering techniques he displayed astonished all the spectators, including the aircraft manufacturers. Thibba, with over 5000 flying hours, was not only one of the most experienced pilots, he was one of the most innovative pilots and was able to “make even the impossible possible.”

Thibba met Asintha Jayawardane, former Vishaka Vidyalaya Western Band Leader, through his batch-mate and pilot buddy TTK Seneviratne ( who died in an SIAI-Marchetti crash at Beruwala on 26th March 1986 with pilot, Officer Cadet Ruwan Punchihette). Asintha is TTK’s cousin. After a few years of association, they got married on 8th March 1990. Asintha and Thibba had decided to stay at Ratmalana Married Officer’s quarters. They were blessed with two sons, Menuka and Diluka.

Thibba was a very trusted and very sincere friend to many. He was chubby, round-faced and always with a smile, blessed with a great sense of humor and was extremely kindhearted and sympathetic towards everyone. These qualities were displayed many times to security force personnel who were at Palali Airport waiting desperately to go back home. Especially if your name was not in the flight manifest, you earnestly prayed to be sent by Thibba in his AVRO, Y-8, or Y -12. If he comes, he will ensure that you will be onboard. There was a period where Thibba was flying AVRO aircrafts continuously without any rest. Nobody knows how many casualties he flew. He had spoken to most of them personally, and reassured them, wishing them a speedy recovery. How many lives Thibba has saved is anyone’s guess. On many occasions, he has gone to the extent of arranging his vehicle to transport colleagues to let them attend family events, like birthdays or weddings. He has also spoken to his Zonal Commander during the flight and has arranged transport for others on many occasions regardless of rank or file.

‘No’ and ‘can’t’ were nonexistent in his vocabulary. If anyone ever wanted anything of him, he would do his utmost to oblige. He would even go to the extent of bending the rules as his desire to be of help to others took precedence over everything else. In short, “he had a heart of gold”. To add to his heart of gold he was blessed with exceptional skills and nerves of steel. He was a pilot par excellence. Adverse and risky encounters he took on his stride. It was almost second nature to him. On two occasions he had landed SLAFs “trusted Old War Horse” Avro’s with jammed nose wheels, for example. His dedication and commitment to duty were way beyond what was expected and he had been commended personally by the Commander of the Air Force on several occasions.

Operation Rivirasa was a combined military operation launched by the Sri Lankan Armed Forces in Jaffna in October 1995. The primary objective of the operation was the capture of the city of Jaffna and the rest of the Jaffna peninsula from the LTTE It is believed that Operation Riviresa was the largest and most successful military operation at that point in time. SLAF flights were fully engaged with heavy flying commitments and SLAF had lost three Transport and Ground Attack Aircraft during 1995 due to terrorist missile fire and none of them survived. The ever-present possibility of a surface-to-air missile was a relatively new phenomenon in the war and even though the pilots were well aware of the imminent danger there were many brave pilots like Thibba who volunteered to fly to Palali to facilitate troop movements and keep the vital air supply line open.

On 18th Nov 1995, there was a very important flight to be made, with a consignment of urgently needed military cargo for advancing troops of Operation Rivirasa as they were just two kilometers from the City of Jaffna. Around 6.00 am on that fateful day Thibba on his Maruti Jeep went to pick Sqd Ldr Lalith Nanayakkara,and then to pick up Sqd Ldr Bandu Kumbalathara. The flight was a Y-8 that could carry 120 onboard or 20,000kgs of cargo. Onboard with Thibba as Captain, Copilot Sqd Ldr Bandu Kumalatara, Squadron Leader Lalith Nanayakkara as Engineering Officer with Flight Lieutenant Prasanna Balasuriya as communicator, Flying Officer Sanjeewa Gunawardena the navigator, and Corporal Jayasinghe as loadmaster. They took off from Ratmalana by 6.50 am. When they hit 13,000 feet and approached Mannar Island they were all alert and serious about the territory and maintained a safe distance from the coastline to avoid possible ground attacks by the terrorists. Using a pre-arranged coded message Thibba informed the Palali control tower of their estimated time of arrival and started descending. Thibba reduced the engine power and set the Y – 8 in the descending altitude. The most prudent and safes air-path to Pallali was over the sea as the runway was only one kilometer from the coastal belt. Flying Officer Sanjeewa Gunawardane was searching for any unidentified boat movements as the sea was very calm. The flight now descended to 500 feet and speed was almost 300 kmph. They were 7-8 Kms from the airfield but over the sea as they did a low-level approach to avoid possible enemy missile attacks from the uncleared Thondamannar area. SL Navy Dvoras were visible patrolling the area as well as an armored helicopter already placed on their approach path to protect the Y-8. They descended to 300 feet now, and the runway and Palali communication tower were visible. Just then the navigator Fly Off Sanjeewa Gunawardane shouted “two high-speed boats are approaching on our left.” At the same time, Palali Control Tower also informed the same but before they could complete the message they heard the loud explosion on the left-wing.

Simultaneously the Aircraft went into an uncontrollable nosedive. Thibba and his co-pilot Kumbalathara tried their best to control the plane but within a few seconds of the explosion, the Shaanxi Y- 8, one of the most popular Aircraft of SL Security forces crashed into the sea almost 3 kms from the coastline with 6 persons onboard and a payload of 35,490Kgs. Before the huge aircraft submerged Thibba, Co-pilot, and Flight Engineer managed to creep through a window and get out of the Aircraft. They removed their boots and were floating expecting the hovering Helicopters which were giving air cover or Naval boats which were giving sea cover to come and rescue. Both Thibba and his Copilot were great swimmers having participated in the Mt Lavinia 2 miles swimming event as schoolboys, but unfortunately, the Flight Engineer was not good at swimming. By this time they were caught in the crossfire between Navy and LTTE. Flight Engineer Sqd Ldr Lalith Nanayakkara was a big made officer and bigger than Thibba. Thibba tried his best to hold him and swim and Kumbalatara drifted away with the waves. The rest of the crew were sadly trapped in the aircraft not being able to come out and they went down with the Aircraft. The BELL 212 helicopter which was hovering above was unable to reach them as the fire from LTTE was so intense. The Helicopter crew spotted the copilot who was drifting towards the other side and they threw an inflated tube connected to a lifeline and rescued him into the chopper.

Later Thubba and Lalith Nanayakkara were spotted floating very close to each other and their heads were beneath the water. They both were unconscious and the helicopter crew could not take them on board and the pilot directed Naval crafts to that location and flew off to Palali. Naval crafts managed to reach Thibba and Nanayakkara and took them to Palali Military hospital, but sadly by that time both were pronounced dead.

Wing Commander TJCB Thibbatumunawe RWP had made the supreme sacrifice not just protecting his Motherland but also doing his utmost to save his friend and colleague. Later that afternoon a Sri Lanka Air Force Antonon AN 32 carried the bodies of Thibba and Nana to Ratmalana. The next day the body of Bala was found trapped inside the ill-fated aircraft by divers but the bodies of Fly Officer Sanjeewa Gunawardane and Sgt Jayasinghe were not found. Thibba being an experienced swimmer and lifeguard had done his utmost to help his Flight Engineer even at the last minutes of his life. Thibba being a strong swimmer there was every possibility that he could have saved himself by swimming towards one of the Naval vessels which were in the vicinity. But our Thibba, “The Lion Heart” ,was not going to let go of his mate to save himself.

Thibba’s body was taken to their residence at Wewalduwa Road Kelaniya and the funeral was held on the 20th evening with full Military Honors at Borella Kanatta amidst a large gathering of Military personnel, his college friends, and relatives. To bid my final farewell to my dear friend Thibba was a heart-wrenching moment for me. What he said to me at our former schoolmate IP Athula Perera’s funeral was ringing in my ears –”You got a good eye for detail Machan, so please do the same at my funeral aswell, and check that everything is in its correct place, if I die during the war”. Through tear-filled eyes, when I looked, there was nothing left for me to do, everything was in perfect order. Only survivor Wing Commander Bandu Kumbalathara retired from SLAF in 1999 and is now a Captain for Sri Lankan flying A320/A330.

At the time of Thibba’s sudden demise, his loving wife Asintha was six months pregnant with their third son. The eldest Menuka was just 5 years and Dliuka was 3 1/2 years. Asintha being a courageous lady singlehandedly brought up the 3 children with sheer dedication and commitment. She volunteered to offer her services at Ananda primary Library as Librarian until her three sons completed their primary schooling. She was a dedicated mother and was right behind her three sons when they were doing after school activities. She truly was Mother Courage personified. Like Thibba all three sons were highly involved in Swimming and Basketball and they won Island championships while representing Ananda. The eldest, Menuka, joined Sri Lanka Air Force as a Pilot like his beloved father and he is a Flight Lieutenant and Helicopter Pilot based in Anuradhapura Air Base MI Squadron.

Menuka married Sahani Jayathilake ( Familien, Executive in Commercial Bank) on 16th May 2019 and were blessed with a baby boy, Ayuk Kiveth Bandara Thibbotumunuwe ( 4th Generation of Anandians)

Second son Diluka, former National record holder for breaststroke with many national records for swimming and also a South Asian Games Bronze Medalist while still a schoolboy at Ananda joined Sri Lanka Navy and is presently holding the rank of Lt attached to an Auxiliary Vessel A521 as a Diving Officer. Diluka is a qualified Diver having completed specialized courses in China and India and winning the accolades of Best Clearance Diving Officer and Best Combat Diver. Diluka got married to Madusha Welihinda (Vishakian, Senior Software Engineer at IFS) on 8th January 2020.

The youngest son, Chamika, who had not seen his father, is reading his MBA at the University of Wolverhampton after graduating with first-class Honors.

It is now 25 years since Thibba left us forever. We all miss him dearly but still relive some of the wonderful memories he left us with. Where ever he may be his heart must be filled with pride at how his boys have turned out to be. Asinitha the love of his life took on the mantle of bringing up his sons for both of them. How proud and happy he would have been to be with his family and friends today. We miss you Thibba but we all are so proud and privileged to have known you and thankful for the time we shared with you. I wish to end this tribute to my gallant friend with the following dedication to Thibba.

With nerves of steel and a heart of gold

Thibba you Legend – our Flyer so bold

Three sons and a loving wife, you cherished to hold

You left behind with sorrow untold.

You served Sri Lanka with flamboyant flair.

Always considerate kind and fair

You flew many sorties with no rest or care

You were the best – a flyer so rare.

From where you left, your sons take on

Protecting Lanka – their lives go on

Brave Flyer, true friend, you soldier on

You may be gone but your legend lives on…….

May you Rest In Peace my gallant friend and may your journey through Sansara be short.

Features

Trump’s Delinquent War Game: No Early End in Sight

It is fruitless analyzing US President Trump’s reasons for going to war with Iran or the conflicting outcomes he says he is looking to have in the end. It is quite possible that he may have made the decision to attack Iran after being cajoled by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is a good time to attack because Iran is at its weakest moment yet posing an imminent threat warranting a pre-emptive attack. Strange and circular reasoning is needed to justify unnecessary wars.

True to form, Trump did not consult any of his western allies the way his predecessors did in similar situations. He ignored NATO as much as he ignored the UN. Nor did Trump go through the internally established broad consultation and focused decision making processes that US presidents usually undertake before committing American forces abroad. The Congress, the institution under Article I of the American Constitution, was also habitually ignored .

It is likely that Trump secured tacit support from other Middle East governments, especially the Gulf states of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE and Oman that are Iran’s neighbours. The latter may seem to have been hoping to have it both ways – letting US and Israel take out Iran’s reprehensible regime while appearing to stay neutral in the fight. That calculation or miscalculation explosively backfired when Iran started firing drones and missiles not only into Israel but practically into every Arabian (Persian) Gulf country, hitting not only American bases but also civilian centres. The welcoming reputation of the Gulf countries as secure oases for foreign investment, tourism, sports and entertainment has been seriously shattered.

Escalating War

In addition to the six Gulf states, Iranian missiles have reached Iraq, Jordan and far away Cyprus. Even Turkey and Azerbaijan have been targeted. Israel has been hit and has suffered casualties far more in the few days of fighting than it has in all the past aerial skirmishes. The US outposts are under attack as well. The Embassy in Kuwait was hit on Monday. The next day two drones fell on the US Embassy in Riyad, Saudi Arbia, apparently the most fortified American outpost abroad. This was followed by drone attacks on the US Consulate in Dubai and on the American military base in Qatar, the largest in the region. Six American servicemen have been killed and 18 injured in the first four days of the war.

The Trump Administration that has been notorious for picking countries to deny US visas, is now asking Americans to return home from 14 Middle East countries for the sake of their own safety. Washington has closed its embassies in Riyadh and in Kuwait and has ordered non-emergency staff and families to depart from its other embassies in the region. But leaving the embattled region is not easy with flights cancelled and air space closed. Belatedly, the State Department is scrambling to make arrangements to help stranded Americans find their way out by air or by land to neighbouring countries. It is the same story with governments of other countries whose citizens are living and working in large numbers in the Middle East. The monarchs of Middle East depend on migrants of many hues to do their blue collar and white collar labour while keeping their citizens in cocoons of comfort. That equilibrium is now under threat.

Iran’s losses are of course significantly higher, already hit by over 2,000 Israeli and US missiles reaching multiple targets in 26 of Iran’s 31 provinces. Over a thousand people have been killed including 180 students in a girls’ school in the south. Buildings and infrastructure and installations are being devastated. Israel has opened a full second front in Lebanon using the thoughtless Hezbollah’s aerial provocation as excuse for once again badgering Beirut and its suburbs. A week into the war there is no early end in sight. Only escalation.

Not only Iran but even the US is extending the waves of war. A US submarine torpedoed without warning and sank the IRIS Dena, a Moudge-class Iranian frigate, in the Indian Ocean not far from Galle. The frigate had about 130 sailors on board and was sailing home after participating in the International Fleet Review (IFR) and multilateral exercise, MILAN-2026, organized by the Indian Navy at Visakhapatnam. The frigate was reportedly not carrying weapons in keeping with the protocol for international naval exercises. Also, according to reports, Americans were in the know of the Fleet Review in India and its participants. Yet the US Secretary of War, Pete Hegseth, went on public television to say: “An American submarine sunk an Iranian warship that thought it was safe in international waters,. Instead, it was sunk by a torpedo. Quiet death.” How tragically surreal!

It fell to little Sri Lanka to respond to the distress call of the sinking sailors. Sri Lanka’s navy and emergency services have done an admirable job in fulfilling their humanitarian responsibilities. The Sri Lankan government has also handled a difficult situation, complicated by a second Iranian ship, with poise and purpose. On the other hand, unless I missed it, I have not seen any official reaction by the Indian government to the reckless sinking of one of its guest ships. An opposition parliamentarian of the Congress Party, Pawan Khera, has been cited as asking on X, “Does India have no influence left in its own neighbourhood? Or has that space also been quietly ceded to Washington and Tel Aviv?”

India is not the only one that has ceded space and time to the bullying whims of Donald Trump. With the exception of Spain, the entire West is literally genuflecting for fear of getting hit by tariffs. Notwithstanding the US Supreme Court ruling much of Trump’s tariffs to be illegal, and a Federal Court now ordering that the collected monies should be paid back to those who had paid them. The situation is a far cry from the European reaction and the public lampooning of Bush and Blair when they went to war in Iraq two decades ago.

The Missile Math

Two factors may objectively determine the course and the duration of Trump’s war: weapons stockpiles and the oil and natural gas markets. Higher prices of oil and natural gas will increase domestic pressure on Washington to find an offramp to the war sooner than later. Other countries may have to suffer not only higher prices but also shortages of fuel. The weapons are a different matter.

The ongoing aerial warfare involves the use of drones and missiles to attack as well using defensive missiles to detect and destroy incoming projectiles before they hit their targets. After the beating it took last year and this week, Iran has no missile defense system to speak of, but it has both a stockpile of drones and missiles and capacity for rapidly producing them. The military question is whether Iran’s stockpile of offensive drones and missiles can outlast the combined defensive missile stockpile of the US, Israel and the Middle Eastern countries. There is no clear answer, only speculations about Iran and US concerns over its own stockpile.

The “troubling missile math,” as it has been called is underscored by the concern expressed by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, that Iran has the capacity for “producing, by some estimates, over 100 of these missiles a month. Compare that to the six or seven interceptors that can be built a month.” The worry is also about the depleting impact that the extended use of interceptors against Iran will have on American stockpiles elsewhere in the world, especially in areas involving China. That is part of the standard military calculation. What is bizarre now is that after starting the war on a whim last Saturday, Trump is convening a meeting within a week on Friday with weapon manufacturers to urge them to produce more.

Secretary Rubio also added that destroying Iran’s missile capacity is the goal of the US campaign. Iran’s missile capacity involves different missiles with different flight ranges. The shorter the range the larger the stock. Iran does not have the standard two-way intercontinental ballistic missile, and it is nowhere near developing them. The current Administration has recklessly claimed that Iran is capable of launching missiles to hit America and has unfairly named and blamed all previous presidents for not doing anything about it.

Trump’s predecessors were fully aware of America’s unmatched military superiority and Iran’s utter limitations. They were also aware that going to war with Iran to destroy its drones and limited range missiles will create more problems without solving any. The Obama Administration in consort with China, UK, France, Germany and Russia produced the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) committing Iran to have nuclear programs for peaceful uses only. Trump tore up the Obama plan and instead of using the opportunity this year to create a new and stronger program, chose to start a war instead.

As things are, unless the US-Israel axis succeeds in literally obliterating all drones and missile production resources in Iran, Iran will retain the capacity to produce drones and short-range missiles with which it could torment its neighbours for long after Trump and Netanyahu declare the war to be over. It may never be a long-range menace – in fact, it never was – but it could become an even greater short-range nuisance.

The US is no longer indicating a time limit for the war to end. For Netanyahu, it is not going to be an endless war. Of the two, Israel might be having some clear objectives to be achieved before ending the war. For Trump and his Administration, on the other hand, the objectives of the war are chaotically evolving on a daily basis, and the world will have to wait till the man of the deal finds some outcome or outcomes that can be shown as success and call it quits.

Regime Change: Insult after Injury

Iran’s Supreme Leader and forty or so other top Iranian leaders were taken out in the first minute of the fight by “pinpoint bombing”, as Trump boasted in his auto-poetic truth social post. But the Iranian regime has not collapsed. It has shown remarkable structure and durability despite the death of its Supreme Leader. It is America that is showing its inability to contain its Supreme Leader from going berserk on the world through tariff and bombing terror – in spite of all the checks and balances that Americans thought they have constitutionally practised and honed over 250 years. It is also poetic comeuppance for the Iranian regime that, after 47 years, it should now face its undoing by an unhinged American hegemon for theocratically subverting the 1979 revolution from realizing any of its secular possibilities.

Trump now wants to add insult to injury by forcing himself into the succession process for selecting a successor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Iran has a well-established succession process, almost akin to the conclave in the Vatican, in which a body of 88 elder clerics, the Assembly of Experts, are convened to elect through a secret vote the new Supreme Leader. Over the last few days, it has been widely reported that the late Khamenei’s 56 year old son Mojtaba Khamenei has emerged as the leading candidate to succeed his father as the next Supreme Leader. His political strength and leadership claim are reportedly based on his close connections to the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Mojtaba is said to have been the shadow Supreme Leader in recent years making decisions in place of his ageing father. For that reason, he is reviled by Iranians who are opposed to the regime and who have been oppressed by the regime. There are also allegations and rumours about his amassing wealth and investing in properties and opening bank accounts in London and Geneva. At the same time, there could also be sympathy for him in the ruling circles because it was not only his father and his mother who were killed in the first minute bombing but also his wife and his son. While ideologically he has been a hawk, Mojtaba is also described as a “pragmatist.” Being pragmatic in the current context, according an unnamed Tehran academic, would imply that Mojtaba Khamenei will be seeking revenge for the US-Israeli attacks on his family and his country – not through victory in war but by ensuring “the survival of the Islamic Republic.”

President Trump is not bothered about the dynamics and nuances of Iranian leadership politics and has no hesitation in inserting himself into the succession process. In an interview with the American news website Axios, Trump has declared that he wants to be personally involved in the Iranian succession process, and that the selection of the younger Khamenei would be “unacceptable” to him, because “Khamenei’s son is a lightweight.” “I have to be involved in the appointment, like with Delcy [Rodríguez] in Venezuela,” Trump went on, because “we want someone that will bring harmony and peace to Iran.”

Comparing Venezuela and Iran is no less preposterous than the Bush Administration’s decision to invade Iraq in addition to Afghanistan in order to punish Al Quaeda for 9/11. Trump now appears to be seeking not a wholesale regime change but a retail leadership change in the old regime. This is only the latest addition to his lengthening wish list for the war with no method or plan to achieve any of them. Add to the growing list the news that the CIA is putting together a Kurdish insurgent force to foment “a popular uprising” within Iran.

That would be back to the future and the return of the CIA, but in a totally different situation from what it was 73 years ago when the CIA, in partnership with Britain’s MI6, staged the 1953 coup that ousted the government of then Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and reinforced the monarchical rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. The purported plan now is to arm and organize Kurdish forces in Iran and Iraq to engage the Iranian security forces and thereby to create internal spaces for Iranian civilians to come out to the streets and take over their country. Those who are entertaining this plan are also aware of its inherent dangers and cross-border and pan-ethnic implications for Iraq and even Turkey and Syria. Trump is reportedly aware of the plan but may not be bothered about its unintended consequences.

by Rajan Philips

Features

How Helmut Kohl braved the tsunami, P-TOMs and Kadirgamar assassination

This is the place to introduce the episode of ex-Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany. “This legendary unifier of post war Germany was at a small hotel in Hikkaduwa undergoing Ayurveda treatment when the Tsunami struck. A German Minister who owned a house in Hikkaduwa and visited Lanka regularly had recommended Ayurveda treatment to The Chancellor and head of her party- the Christian Democrats.

The German Embassy was at its wits end because Kohl had disappeared without a trace. They contacted us and we activated our Grama Sevaka network to find that Kohl had been taken to the safety of his home by a hotel employee. When we offered to send a helicopter to bring him to Colombo the Chancellor had replied that it was not necessary as he was well looked after by his host. He came by car the following day in order to thank CBK for her help.

I went to President’s House with Kohl who seemed quite relaxed in his coloured shirt, crumpled pants, a grey seersucker coat and rough boots. He was full of praise for the Sri Lankan people who had helped him and all the tourists in distress due to the Tsunami. Kohl said that he wanted to help in the rehabilitation of the south in his personal capacity. When he got back to Germany he set up a group of rich friends called “Friends of Helmut Kohl” who sent money to build a hospital in Mahamodera, Galle.

The money was lodged in the German Embassy. But the usually lethargic Health department dragged its feet on the construction work on the guise that the money was not sufficient for their grandiose hospital plans ignoring the value of the superb gesture by Kohl. Unfortunately he died before the completion of the project and therefore could not keep his pledge to come to Galle for its opening.

Later in time I was a member of a Parliamentary delegation led by Speaker Karu Jayasuriya which included Sampanthan, Rauf Hakeem, Anura Dissanayake and several others. I suggested to our group that we pay a belated tribute to Helmut Kohl who had died a few months previously. This was immediately welcomed by the parliamentarians and the organizers of the tour and we jointly paid our heartfelt tribute to a great friend of Sri Lanka who was an eye witness to the success of our rehabilitation effort.

Post Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS)

The Tsunami was particularly harsh on the eastern and northern coastline because it was directly in the way of the giant waves created in Indonesia and deflected to our shores. It also created a transformation of the political scene and the nature of the war. The LTTE had invested considerable resources in building up its “Sea Tigers”. They wanted control of the northern seas in order to increase their supply of weapons and ammunition. The Sea Tigers established a presence in east Thailand so that arms could be purchased from Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. The fighting in the Indo-China theatre was over and the cut rate weapons market was flourishing.

Our embassy in Bangkok had an army officer who was monitoring terrorist activities but he was helpless because Thai officials in the lower echelons were in the pay of the LTTE. In addition to that problem, the mediocre officials of our Foreign Ministry were no match for the determined LTTEers one of whom had married an influential Thai lady. With money coming in from expatriates they had even set up a shipping line which was so well run that they could finance weapons buying for the LTTE with its profits.

We had received intelligence that the LTTE was preparing for a major “Sea Tiger” operation from their base in Mullaitivu. This base area concept shows the advanced thinking of the LTTE which was attempting – then unsuccessfully – to even manufacture a low cost submarine. Fortunately for us the Tsunami wiped out the base of the “Sea Tigers” together with many of their assets such as boats, proto-type submarines and diving gear.

True to form they sent signals for talks which they had earlier broken. Their diaspora had mounted a campaign to collect funds for rehabilitation. At this stage the UN got into the act and with the World Bank and IMF persuaded the CBK government to consider a power sharing arrangement principally for the rehabilitation of the North and East. It was to be called P-TOMS. CBK appointed Jayantha Dhanapala as the head of SCOPP – a secretariat to coordinate the relief effort in the North and East. The World Bank appointed Peter Harrold, its representative in Colombo, to coordinate the P-TOMS effort with SCOPP.

Estimates were made by SCOPP regarding the amount necessary for the rehabilitation of the North and East. This budget became the talking point of several successive regimes who promised to allocate such funds in exchange for Tamil votes in the North. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s agents held this figure as a bait to promote a boycott of the Presidential poll in 2005 which threw the election which was in Ranil’s pocket to MR thereby changing the destiny of the LTTE as well of the country. [MR cleared the 50 percent hurdle by only 25,000 votes].

Perhaps to strengthen the push for P-TOMS, Kofi Annan the Secretary General of the UN arrived with a large contingent of staffers and I was asked to meet and greet him in Katunayake. We gave Annan a grand welcome but he seemed distracted and was only interested in getting his Swedish wife who was hanging back, into the spotlight. CBK had several discussions with him but we ran into a snag in that he wanted to visit the North and meet Prabhakaran.

Perhaps some of the big powers had got to him as he was in the midst of a scandal about his son from his first marriage who was facing charges of corruption. The scandal was rocking UN headquarters. Annan who was elevated from his earlier status as a UN functionary to satisfy African members, was according to several biographers, indebted to the west and could not end his tenure to the satisfaction of the majority of the UN membership.

CBK, already under pressure for mishandling the P-TOMS campaign, was adamant that Annan should not meet the LTTE which would have given the terrorists parity of status with the SL state. Since such an interpretation was circulated by virtually all political parties in the South she was pushed to a very difficult position. After much discussion Annan settled for a helicopter tour of the North. I found that he was a weak leader who was led by his nose by Mark Mallock Brown – his chief of staff, who had been in charge of UN operations even during its disastrous forays in the Congo.

Mallock Brown was later identified as a camp follower of the West who compromised the credibility of the UN. I have memories of Mallock Brown holding forth on their next step here while Annan and Dhanapala were mere passive listeners. This Western initiative of P-TOMS did not finally see the light of day. But it split the ruling coalition of the PA and JVP irrevocably and Mahinda Rajapaksa burnished his credentials as an opponent of the project. He became popular with the PA and its allied parties over and above CBK.

When the P-TOMS project was to be placed before Parliament Mahinda as Prime Minister refused to present it on the floor of the House. CBK was too weak to dismiss him partly because Lakshman Kadirgamar also was a strong opponent of P-TOMS. Instead she got Maithripala Sirisena to present the proposal. But the Opposition which was joined by the JVP including its functioning Ministers, took to the streets. The JVP members demonstrated and disturbed the proceedings from the well of the House and then resigned “en masse” from the government putting its majority in jeopardy. Mahinda’s anti-P-TOMS stand endeared him to the JVP, which had earlier preferred Kadirgamar to him, and helped him to garner votes which went a long way in ensuring his ultimate victory. He had become so powerful that CBK had no option but to accommodate him.

Assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar

Another blow was struck at CBK and the government by the I TTE when they assassinated Lakshman Kadirgamar near the swimming pool of his house. He had a successful kidney transplant in India – with a Buddhist monk from Balangoda donating a kidney – and was asked to swim regularly as exercise by his doctors. I knew of this arrangement because when we travelled together he always asked the Foreign Office to put him tip in a hotel with a heated swimming pool.

He was about to enter the water in the swimming pool when a LTTE sniper shot him through a window in a neighbourhood flat. This dastardly crime wits condemned unanimously by the international community. India sent her Foreign Minister to attend the funeral. Ksdirgamar’s death brought CBK’s Government to the brink of collapse. The JVP though leaving the Government respected LK and paid a tribute to him by arranging for their leaders to follow his hearse on foot to Kanatte.

It must be mentioned here that LK nearly pipped Mahinda for the post of PM in 2004. He had the backing of the JVP who wanted CBK to appoint LK and in the alternative appoint Maithripala Sirisena as PM. He was also supported by India but CBK was afraid that Mahinda will break up the party if he was deprived of the Premiership. After LK’s demise she undertook a mini reshuffle and Anura Bandaranaike had his ambition of being Foreign Minister realized.

To succeed him as Minister of Industries and Foreign Investment she appointed me in addition to my portfolio of Minister of Finance. Arjuna Ranatunga was the Deputy Minister of Industries and I left most of the administrative work to him. When we had an investment promotion meeting in Delhi I invited Arjuna and Aravinda de Silva to be our delegates and they stole the show among the cricket mad Indian investors. All the tables at dinners hosted by us were taken and we had many friends appealing to us to get them reservations even at the last minute.

We had such good relations that I was invited to take part in popular TV talk shows. I remember that Shekhar Gupta invited me for a discussion on our health services with Kajol – the top Hindi film actress who was brand ambassador for Narendra Modis “clean Bharat” campaign. She was a charming young lady who recounted her enjoyable stay in Sri Lanka when she accompanied her mother Tanuja who was shooting a film in Colombo with Vijaya Kumaratunga as her co-star.

After LKs murder the fear of the LTTE was so strong that CBK could not even attend the funeral ceremony. PM Mahinda Rajapaksa represented her. This death was a bitter blow to me because as an old Trinitian friend he would always consult me on party matters. I still have a letter he wrote to me about a coffee t able book on the art of Stanley Kirinde which he sponsored in honour of our mutual college friend.

(This book is available at the Vijitha Yapa bookshops)

(Excerpted from vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography)

Features

The amazing biodiversity of Sri Lanka:

Nations Trust WNPS Monthly Lecture

An overview of the plants & animals on this magical island

Thursday 19 March 2026, 6.00 pm, Jasmine Hall, BMICH

In the first part of this talk, Author-Photographer Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne points out that Sri Lanka is disproportionately rich in species. He presents possible reasons for this and then makes the case that Sri Lanka is one of the best all-round wildlife destinations in the world. In the second part of the talk, he takes a whirlwind tour of several branches of the tree of life from bacteria to elephants. He uses this tour of life forms as a framework to showcase the richness of biodiversity in Sri Lanka.

He points out that very little has been done on the study of groups such as fungi and mosses and remarks how his proposal for a special visa for exchange programs, internships and volunteering could enable local academics to gain access to expertise and experienced volunteer hours from people overseas who have a passion for these areas of natural history.

With plants, he outlines the major groups of plants which are the bryophytes, lycopods, ferns and spermatophytes. The latter also knows as seed plants include the conifers (gymnosperms) and flowering plants (angiosperms). He makes reference to what is found in Sri Lanka to illustrate the importance of certain groups, such as the dipterocarp trees which are the giants of the rainforest. His photographs will illustrate examples such as carnivory, because plants employ a wide range of life strategies.

The talk will provide a very brief outline of the animal kingdom with its vast and sprawling evolutionary tree. Starting with animals that evolved early such as the sponges, he will draw attention to a few of the phyla which holds larger animals. Not surprisingly, more attention will be given to the vertebrates which command most of the popular attention. However, he will also reference invertebrate groups such as the butterflies and dragonflies, the two most popular groups of insects. Although Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne was the first to brand Sri Lanka for big game safaris, in this talk, he will bring in many of the other plant and animal groups which although lacking ‘safari appeal’ are nevertheless important in terms of biodiversity and being the subjects of research.

As Sri Lanka positions itself as a destination for high-value, experience-driven tourism, the conservation of its natural heritage becomes not just an environmental priority but an economic imperative. This lecture will be especially valuable for tourism professionals, hospitality leaders, policymakers, conservationists, students, photographers, and nature enthusiasts seeking to understand the true asset underpinning Sri Lanka’s future.

According to Rohan Pethiyagoda, ‘Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne is without question the most celebrated field naturalist the country has produced’. Bill Oddie (British TV Naturalist) has said no single individual has done so much to publicise a country for its wildlife. The speaker has authored and photographed more than 25 books and 400 articles and has played a pivotal role in branding Sri Lanka as a wildlife destination.

The WNPS Monthly Lecture Series, established in 2000, is one of Sri Lanka’s longest-running and most respected conservation knowledge platforms. Featuring leading local and international experts, the series addresses critical environmental issues through science-based insights and open public dialogue. Beyond the lecture hall, these sessions foster collaboration, inspire research, and often seed conservation projects and advocacy initiatives. The series remains a cornerstone of Sri Lanka’s conservation community—connecting knowledge with action

The Lecture is supported by Nations Trust Bank and is open all, entrance free

- Sloth Bear – Yala (pix by Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne)

- Sperm Whale – Kalpitiya

- Sri Lanka Blue Magpie – Sinharaja

- Toque Monkey – Hakgala

- Water Monitor – Diyasaru

- Ceylon Tree Nymph

- Leopard

- Adam’s Gem (Libellago greeni) male – Talangama

- Indian Sunbeam – Beddegana

- Green Pit Viper – Sinharaja

- Dichrostachys cinera – (Andara) Yala

- Asian Elephant – Yala

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoWar in Middle East sends shockwaves through Sri Lanka’s export sector