Features

The Copper Tumbler and Donkeys in Mannar: A Work of Mourning – IV

‘it is not narrative that we should abandon but chronology’’

Kumar Shahani

By Laleen Jayamanne

Mourning the Dead: Phaneroscopy

“There is a reality which we each create in our own minds.”

(C.S. Peirce)

The American logician and semiotician C.S. Peirce using the Greek word phaneron, meaning ‘that which appears,’ and adding the suffix skopein, (the Greek word to see, as in Bioscope!), coined the term phaneroscopy. He wanted thereby to capture something common to how we all perceive. He didn’t want to call this subjective mode of seeing an ‘illusion’ or ‘fantasy’ posited against ‘reality’. He elaborated his idea of ‘phaneroscopy’ by saying it is a way of seeing which is not cognitive (being prior to it), a pre-logical, direct awareness, without ego. I think this is much like the way a child, presumably, sees the world before it’s captured in language. Sumathy gives Lalitha phanero-scopic powers. So, as she slowly begins to remember her own childhood in that house, absorbed in the photographs of Jude and of herself as a girl, becoming reflective, but also prodding her siblings insensitively about what actually happened during the war to both the Muslims and to Jude, she begins to perceive visually, what she hears. She herself appears within each of the following events, from which she was in fact absent, away in Canada.

Most of the framed photographs we see in the house are from Sumathy’s own childhood home in Jaffna which she shared with her parents, three sisters and also her two nieces. Even before I learnt this detail, I felt that this home had a shadow cast on it by Sumathy’s own family history which is now public. So, it is the most personal of her films, but she uses her autobiography to testify to those innumerable nameless Muslim folk, too.

The house has shadows, ‘ghosts’ who come in and out. The brother who disappeared, Jude, comes in and out of the film, just as Fatima Teacher does, both as a young woman carrying her precious possessions and then as an old woman. Intriguingly, Sumathy only credits one actor, Asiya Umma, as both the young and the old Fatima Teacher, when realistically one would expect two actors to be named. In the course of the monologue, when her mother tells Lalitha that Fatima Teacher stood right where she now stands, the latter appears. As her head is partly covered by her sari, it is unclear if Fatima Teacher is in fact played by Lalitha, who has inserted herself into that story as she hears it narrated by her crazed mother. But the credits resolve it. However, this sense of uncertainty is important because (disturbed by her mother’s accusatory account of Fatima Teacher), Lalitha creates a film-within- the-film, placing herself in the position of the victim. In appearing at that moment as Fatima Teacher, addressing her friend Daisy Teacher, Lalitha performs an act of mourning.

It’s the musical composition of sequences, with intervals, repetitions and disjunctions between them, which allows Sumathy to abandon chronological progression (without using the usual tired devices like flash-backs as memory images), to play with time in this way.

Three different accounts of Jude’s disappearance are given, two shown. There is that dreaded knock on the heavy wooden door late at night, with two men on a motorbike and car, the boys as they are called, to take Jude away. Lalitha in bed with her cell phone hears the knock and goes to the door in her nighty wrapped in a sheet, asking him to not open the door and watches him being taken away by ‘the boys.’ Earlier there is a snatch of conversation that the story is that the army took Jude away. We see him walking to the church to meet two young Catholic priests, to ask them to intercede with the LTTE, on behalf of the Muslims. Within this sequence we are taken into a large Italianate, grand Catholic church with polished pews and woodwork. But we also see Jude walking into the sea, watched by Lalitha, in the film within the film she creates with herself as a presence.

In this strange retelling, Sumathy is able to make the dead Jude testify to the stories of the many disappeared, without ceasing to be that irreplaceable son of Daisy Teacher. That quiet act of Jude’s suicide, witnessed by Lalitha, standing amongst the braying, foraging donkeys, is a ritual of burial and mourning, an epic cosmos-centric event. The old Fatima Teacher also walks through the mangrove, and earlier through the debris of bomb blasted houses (without their solid timber doors and windows), that might well have been her own dense urban neighbourhood.

In this strange elegiac scene by the sea at night, with the wind and sound of waves lapping the shore, Jude slips off his sarong and simply walks into the ocean slowly. The entire qualitative, tonal, atmospheric mood of the scene amidst nature with Fatima Teacher and Jude and the donkeys as they appear to Lalitha, has a ritualistic, musical quality with its varied rhythms. One exiting life and the other returning from the dead, unreconciled, one might say, amidst the sound of waves. After this long sequence, the film cuts to Jude’s naked corpse washed up on the beach at dawn, spotted by two fishermen who look closely and abandon it.

Lalitha asks her mother to sign over the family home to her. The younger brother asks Lalitha to send the monthly payment for their mother’s expenses directly into his bank account. Neither request is granted. The sister who actually takes care of the mother makes no demands of her more affluent sister but complains about the tedium of her life of chores. But the family gather together with affection as well as acrimony and learn of their trauma and the family history. And the terror of the war years is expressed through a truism of that era by Jesse, who has no time or inclination to linger in the past. She quotes a folk saying of the war years when Lalitha bugs her as to why she didn’t call her or write to her: “People here say those were times when one opened one’s mouth only to drink tea”. A biting sentence condenses the lack of food with terror.

Pedagogy of Film Programming: Suggestions

If a mini retrospective of Sumathy’s body of work is organised, then pairing The Single Tumbler with Ponmani (1976), by Dharmasena Pathiraja, could generate a few more ideas about how to creatively engage with linguistically and culturally diverse communities and cultures, without orientalising Northern landscapes and most especially the ‘Tamil Woman.’ Without a public release in the South and an indifferent short run in Jaffna, now Ponmani has the aura of a classic, one of a kind without a progeny.

This is not quite the case. The way the traditional Hindu Vellala home and its veranda is filmed in Ponmani, finds a different articulation in the way the Christian family inhabits the space of the open house, in the fluid spatial configurations of The Single Tumbler. In both films, changing or frozen family relationships are mapped out spatially through evocative gestures, postures and movements. The traditional Hindu home is marked by silences, while the bilingual Christian home with its different culture is voluble, rather urbane. Sumathy has clearly benefited from Pathi’s work in Jaffna though she is no clone.

It is essential not to forget that this singular film Ponmani was made possible by a visionary tri-lingual higher educational policy formulated by Tamil scholars at the Jaffna University. Pathi and several lecturers were sent to Jaffna University to teach there in the Sinhala medium. During this time, his friendship with Tamil intellectuals and artists resulted in the collaborative film, Ponmani. Until about this time Tamil students from Jaffna were able to study at the National Art School in Colombo along with Sinhala students and there were student exchanges of performances with Jaffna. That was of course possible because lectures were delivered in both English and Sinhala, but with the ‘Sinhala Only’ nationalism hegemonic, English was abandoned.

Sumathy’s documentary Amidst the Villus; Pallaikuli (2021), on the effort of the expelled Muslim populations to return to their homelands would also be important as a companion film to The Single Tumbler.

Ashfaque Mohamed’s debut film Face Cover (2022), with its fine spatial sensitivity and sense of tact, might also be screened together with these two films, to create a generative public context and discourse for these films from different generations and by directors from different ethnicities and set in different regions. He was the assistant director on The Single Tumbler. Sumathy has been a mentor to him and also played the Muslim mother in Face Cover.

Also, perhaps a few of Rukmani Devi’s and Mohideen Baig’s films might be part of it, and Sarungale by Sunil Ariyaratne, where Gamini Fonseka plays the role of a Tamil clerk, might also work well in such a non-linear, thematic mix. Sumathy’s Sons and Fathers about the multi-ethnic composition of the Lankan film industry during July ’83, would create a new political perspective on these films. Ingirunthu remembers the disenfranchisement of the tea estate workers at independence and also the deportation of a large number to India in 1964, despite having lived and worked in Ceylon for generations.

Expulsion of the Muslims

The Expulsion of the Muslims (estimated at 75,000), from the Northern Province by the LTTE is an event of epic magnitude in Lankan history. Refusing to forget the event and its aftermath, The Single Tumbler was made in collaboration with a dedicated ensemble cast and crew (with Sunil Perera’s cinematography, Elmo Halliday on editing and sound design, music direction by Kausikan Rajeshkumar), with a modest budget, but with a sophisticated understanding of ‘film as a form that thinks.’

That dented and burned single copper tumbler on fire is hard to forget, just like Sumathy’s other such images powered by fire. The fiery copper tumbler brings to mind two sentences by the French philosopher Deleuze, in a short piece written just before he committed suicide, being terminally ill. The brusque note, written in haste, is called ‘The Actual and the Virtual’.

He says: ‘Purely actual objects do not exist. Every actual surrounds itself with a cloud of virtual images.’ This idea of ‘virtual images’ Deleuze owes to Henri Bergson who wrote a book titled Matter and Memory in 1895, the year the very first films were projected in Paris. And for Bergson, the concept of the ‘virtual’ is opposed to time as chronology, time as the simple linear succession of past, present and future. He says, speaking more like a poet, that the ‘virtual’, or duration, appears to us in its fullness when we are drunk with wine or dream, or in love, when all that has happened coexists in an intense, expansive present, open to a potentialized future. Film is surely the gift that plunges us into this cloud of virtuality – sometimes; as with The Single Tumbler. (Concluded)

Features

The invisible crisis: How tour guide failures bleed value from every tourist

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

If you want to understand why Sri Lanka keeps leaking value even when arrivals hit “record” numbers, stop staring at SLTDA dashboards and start talking to the people who face tourists every day: the tour guides.

They are the “unofficial ambassadors” of Sri Lankan tourism, and they are the weakest, most neglected, most dysfunctional link in a value chain we pretend is functional. Nearly 60% of tourists use guides. Of those guides, 57% are unlicensed, untrained, and invisible to the very institutions claiming to regulate quality. This is not a marginal problem. It is a systemic failure to bleed value from every visitor.

The Invisible Workforce

The May 2024 “Comprehensive Study of the Sri Lankan Tour Guides” is the first serious attempt, in decades, to map this profession. Its findings should be front-page news. They are not, because acknowledging them would require admitting how fundamentally broken the system is. The official count (April 2024): SLTDA had 4,887 licensed guides in its books:

* 1,892 National Guides (39%)

* 1,552 Chauffeur Guides (32%)

* 1,339 Area Guides (27%)

* 104 Site Guides (2%)

The actual workforce: Survey data reveals these licensed categories represent only about 75% of people actually guiding tourists. About 23% identify as “other”; a polite euphemism for unlicensed operators: three-wheeler drivers, “surf boys,” informal city guides, and touts. Adjusted for informal operators, the true guide population is approximately 6,347; 32% National, 25% Chauffeur, 16% Area, 4% Site, and 23% unlicensed.

But even this understates reality. Industry practitioners interviewed in the study believe the informal universe is larger still, with unlicensed guides dominating certain tourist hotspots and price-sensitive segments. Using both top-down (tourist arrivals × share using guides) and bottom-up (guides × trips × party size) estimates, the study calculates that approximately 700,000 tourists used guides in 2023-24, roughly one-third of arrivals. Of those 700,000 tourists, 57% were handled by unlicensed guides.

Read that again. Most tourists interacting with guides are served by people with no formal training, no regulatory oversight, no quality standards, and no accountability. These are the “ambassadors” shaping visitor perceptions, driving purchasing decisions, and determining whether tourists extend stays, return, or recommend Sri Lanka. And they are invisible to SLTDA.

The Anatomy of Workforce Failure

The guide crisis is not accidental. It is the predictable outcome of decades of policy neglect, regulatory abdication, and institutional indifference.

1. Training Collapse and Barrier to Entry Failure

Becoming a licensed National Guide theoretically requires:

* Completion of formal training programmes

* Demonstrated language proficiency

* Knowledge of history, culture, geography

* Passing competency exams

In practice, these barriers have eroded. The study reveals:

* Training infrastructure is inadequate and geographically concentrated

* Language requirements are inconsistently enforced

* Knowledge assessments are outdated and poorly calibrated

* Continuous professional development is non-existent

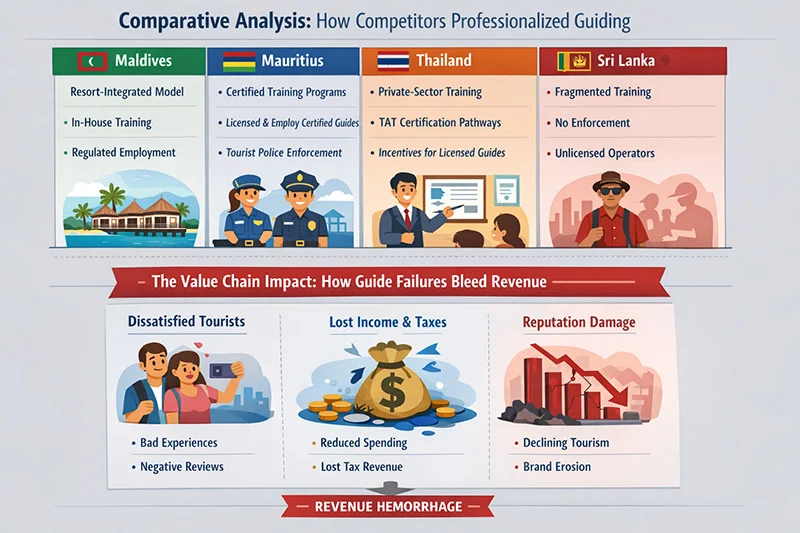

The result: even licensed guides often lack the depth of knowledge, language skills, or service standards that high-yield tourists expect. Unlicensed guides have no standards at all. Compare this to competitors. In Mauritius, tour guides undergo rigorous government-certified training with mandatory refresher courses. The Maldives’ resort model embeds guide functions within integrated hospitality operations with strict quality controls. Thailand has well-developed private-sector training ecosystems feeding into licensed guide pools.

2. Economic Precarity and Income Volatility

Tour guiding in Sri Lanka is economically unstable:

* Seasonal income volatility: High earnings in peak months (December-March), near-zero in low season (April-June, September)

* No fixed salaries: Most guides work freelance or commission-based

* Age and experience don’t guarantee income: 60% of guides are over 40, but earnings decline with age due to physical demands and market preference for younger, language-proficient guides

* Commission dependency: Guides often earn more from commissions on shopping, gem purchases, and restaurant referrals than from guiding fees

The commission-driven model pushes guides to prioritise high-commission shops over meaningful experiences, leaving tourists feeling manipulated. With low earnings and poor incentives, skilled guides exist in the profession while few new entrants join. The result is a shrinking pool of struggling licensed guides and rising numbers of opportunistic unlicensed operators.

3. Regulatory Abdication and Unlicensed Proliferation

Unlicensed guides thrive because enforcement is absent, economic incentives favour avoiding fees and taxes, and tourists cannot distinguish licensed professionals from informal operators. With SLTDA’s limited capacity reducing oversight, unregistered activity expands. Guiding becomes the frontline where regulatory failure most visibly harms tourist experience and sector revenues in Sri Lanka.

4. Male-Dominated, Ageing, Geographically Uneven Workforce

The guide workforce is:

* Heavily male-dominated: Fewer than 10% are women

* Ageing: 60% are over 40; many in their 50s and 60s

* Geographically concentrated: Clustered in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Cultural Triangle—minimal presence in emerging destinations

This creates multiple problems:

* Gender imbalance: Limits appeal to female solo travellers and certain market segments (wellness tourism, family travel with mothers)

* Physical limitations: Older guides struggle with demanding itineraries (hiking, adventure tourism)

* Knowledge ossification: Ageing workforce with no continuous learning rehashes outdated narratives, lacks digital literacy, cannot engage younger tourist demographics

* Regional gaps: Emerging destinations (Eastern Province, Northern heritage sites) lack trained guide capacity

1. Experience Degradation Lower Spending

Unlicensed guides lack knowledge, language skills, and service training. Tourist experience degrades. When tourists feel they are being shuttled to commission shops rather than authentic experiences, they:

* Cut trips short

* Skip additional paid activities

* Leave negative reviews

* Do not return or recommend

The yield impact is direct: degraded experiences reduce spending, return rates, and word-of-mouth premium.

2. Commission Steering → Value Leakage

Guides earning more from commissions than guiding fees optimise for merchant revenue, not tourist satisfaction.

This creates leakage: tourism spending flows to merchants paying highest commissions (often with foreign ownership or imported inventory), not to highest-quality experiences.

The economic distortion is visible: gems, souvenirs, and low-quality restaurants generate guide commissions while high-quality cultural sites, local artisan cooperatives, and authentic restaurants do not. Spending flows to low-value, high-leakage channels.

3. Safety and Security Risks → Reputation Damage

Unlicensed guides have no insurance, no accountability, no emergency training. When tourists encounter problems, accidents, harassment, scams, there is no recourse. Incidents generate negative publicity, travel advisories, reputation damage. The 2024-2025 reports of tourists being attacked by wildlife at major sites (Sigiriya) with inadequate safety protocols are symptomatic. Trained, licensed guides would have emergency protocols. Unlicensed operators improvise.

4. Market Segmentation Failure → Yield Optimisation Impossible

High-yield tourists (luxury, cultural immersion, adventure) require specialised guide-deep knowledge, language proficiency, cultural sensitivity. Sri Lanka cannot reliably deliver these guides at scale because:

* Training does not produce specialists (wildlife experts, heritage scholars, wellness practitioners)

* Economic precarity drives talent out

* Unlicensed operators dominate price-sensitive segments, leaving limited licensed capacity for premium segments

We cannot move upmarket because we lack the workforce to serve premium segments. We are locked into volume-chasing low-yield markets because that is what our guide workforce can provide.

The way forward

Fixing Sri Lanka’s guide crisis demands structural reform, not symbolic gestures. A full workforce census and licensing audit must map the real guide population, identify gaps, and set an enforcement baseline. Licensing must be mandatory, timebound, and backed by inspections and penalties. Economic incentives should reward professionalism through fair wages, transparent fees, and verified registries. Training must expand nationwide with specialisations, language standards, and continuous development. Gender and age imbalances require targeted recruitment, mentorship, and diversified roles. Finally, guides must be integrated into the tourism value chain through mandatory verification, accountability measures, and performancelinked feedback.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Can Sri Lanka achieve high-value tourism with a low-quality, largely unlicensed guide workforce? The answer is NO. Unambiguously, definitively, NO. Sri Lanka’s guides shape tourist perceptions, spending, and satisfaction, yet the system treats them as expendable; poorly trained, economically insecure, and largely unregulated. With 57% of tourists relying on unlicensed guides, experience quality becomes unpredictable and revenue leaks into commission-driven channels.

High-yield markets avoid destinations with weak service standards, leaving Sri Lanka stuck in low-value, volume tourism. This is not a training problem but a structural failure requiring regulatory enforcement, viable career pathways, and a complete overhaul of incentives. Without professionalising guides, high-value tourism is unattainable. Fixing the guide crisis is the foundation for genuine sector transformation.

The choice is ours. The workforce is waiting.

This concludes the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation. The diagnosis is complete. The question now is whether policymakers have the courage to act.

For any concerns/comments contact the author at saliya.ca@gmail.com

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka