Features

The Bandarawela experience

(The war years)

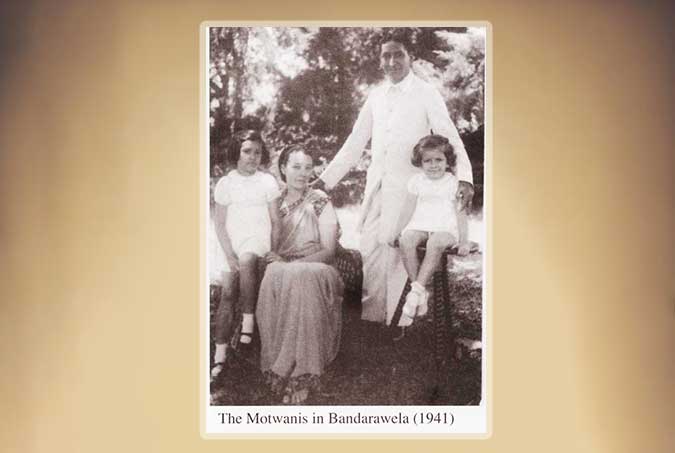

Excerpted from Chosen Ground: The Clara Motwani Saga by Goolbai Gunasekara

When war broke out in 1939 its reverberations were worldwide, of course. Not for nothing was it referred to as World War II. Yet the widening ripples of the dreadful conflict barely reached our shores in Sri Lanka. The British Empire had weathered World War I from 1914-18, and so there seemed to be no good reason as to why we should not expect it to do likewise in 1939. Our confidence in the invincibility of the British Empire was such that even the declaration of war. seemed a far away affair which the British would handle with their customary elan, ensuring that the colonies and dominions were protected at all times.

Wiser local brains saw through the facade of invincibility. They realized quite early in the day that if this island were to be the focus of an enemy attack there was no possible way Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) could be defended. The British knew it and local leaders of the political community knew it — but the population at large did not know it, and thus worry was at a minimum.

It was not OUR war after all. The British ruled us, and the people of Ceylon felt that our rulers were well served by having total access to all our resources — especially our rubber, at prices set in Britain. Had the owners of the island’s rubber estates been allowed to sell their produce in the open market at the time, Sri Lanka might not be in the economic doldrums of today. Similarly, all the island’s assets were regarded as Britain’s by right of conquest, and so Ceylonese felt they had done more than their bit as far as the war was concerned. They settled down to see it through.

The question of ‘evacuation’ trembled in the air. Until such time as schools could be transferred up to the hills, schoolchildren in the coastal areas were taught air raid drill. This provided an exciting little interlude in our daily life. It worked thus. A siren would sound that would be heard all over Colombo. At that signal, school kids dived under their desks, or lay flat in the corridors until the all-clear sounded. Sand bags were piled up on roadsides, and even in schools, giving us a thoroughly deceptive feeling of security. As far as school girls were concerned, it made for a welcome break in the monotony of school life.

Eventually, of course, the Principals of the big Colombo schools began making preparations for an exodus up-country. Schools were soon divided to form an ‘Up-country Branch’ and a ‘Colombo Branch’.

The Royal College buildings in Colombo were taken over by the British Government and so the school transferred to a new location at “Glendale” in Bandarawela. St.Thomas’ College, which already had a branch at Gurutalawa, also went to Getambe. Bishopians trotted off to Kandy, and sited themselves at “Fernhill”. Further up was Ladies’ College in “Uplands”, while the students of Bishop’s College and Ladies’ College who were left behind in Colombo, joined up as the “Lake School” – probably the only time these two rival schools have ever been so close.

Somewhere along the way however, our complacency received a little jolt. Singapore fell and the Japanese were too close for comfort. Schools that could afford a quicker evacuation began moving up to the hills. Visakha soon began this process itself. Under the Principals of these schools (mostly foreigners) work and studies went on without missing a beat. A holiday atmosphere may have been noticeable but it did not penetrate into the classroom agendas. My own mother, as Principal of Visakha, had to divide her time between the Colombo branch and the Bandarawela branch. I presume that all the Principals shuttled up and down in a similar manner. Certainly the train journeys up and down were comfortable beyond belief. Snowy white sheets and fluffy pillows were laid on berths in the First Class carriages, which made the journey totally delightful.

Mother eventually used a personal friendship with Mr. D.G.K. Jayakody who had a large home, “Chandragiri” in the hills of Bandarawela. It was rented by Visakha for the new branch school. Temporary classrooms were built while the main house was used for the boarding. One of Mr. Jayakodys granddaughters, Ramya, remains my close friend to this day and her granddaughter, Saveeta, is one of my pupils at the Asian International School at the moment. Another instance of the circle of life!

Classes began. Mrs. Susan George Pulimood (subsequently Principal of Visakha), and Mrs. Chandra Godakumbure, wife of the later Archaeological Commissioner, were among the numerous excellent teachers who went up to Bandarawela. Mother ran both schools in Colombo and Bandarawela on a shuttle system which seemed to work well enough. She had a great time, enjoying the slightly unorthodox atmosphere. Small classes gave her time to get to know every girl intimately — whether the girls enjoyed such close personal attention was another matter. Mother concerned herself with neat cupboards, clean clothes, hairstyles, diet, personal hygiene, exercise and everything else, not really a Principal’s usual business.

It would be correct to say that these mountain schools, so small in number and in size, functioned as happy families. There were compulsory religious activities, of course. The Bandarawela temples and churches never had so many adherents as they did during the war years.

For excitement and entertainment there were the movies. Whatever Britain was doing on the various war fronts, her colonies received regular inputs from the film studios. Two changes a week was the order of the day. Mother would graciously allow her Visakhians to walk into town to see the latest Greer Garson or Ingrid Bergman offerings (among others) on the silver screen. We thrilled to ‘Dangerous Moonlight’, `Mrs. Miniver’, and other movies of high romance. Films that starred Shirley Temple and Margaret O’Brien were considered suitable for us juniors. To this day I remember the hair of Dr.Thelma Gunawardena (now retired Director of National Museums), done in Shirley Temple ringlets.

In Diyatalawa, three or four miles from Bandarawela, there were two theatres which catered to the servicemen and the general public. If the teachers at Visakha felt particularly adventurous, they would walk the distance and back just to see a film that had been highly publicized. Older girls were allowed to accompany them, and there were some touching incidents.

One of the movies had taken an unusually long time to end, and it was dusk when the Visakha contingent finally emerged from the cinema to begin the long walk home. It was a time when violence was minimal. The whole island was safe, safe, safe. Whatever fear the group might have felt was mainly because of animals that may have unexpectedly run across the road. Buses did not run so late and in any case there was petrol rationing.

Cautiously, the Visakhians decided to set off. Sri Lankan voices are not necessarily soft, and a group of British officers soon caught on that this was a bunch of jittery natives. One of the senior officers approached the group. “I can have you escorted back to Bandarawela,” he said, and proceeded to send two cadets along with the nervous ladies . Naturally they got chatting on the way, and the two young soldiers told the Visakhian group that they were the first Ceylonese who had talked to them, apart from the servants they employed.

Seeing the Visakhians hiking up the Visakha hill with two young British soldiers as escorts almost gave Mother a heart attack. She had visions of angry, tradition-oriented parents getting to hear that their offspring had actually arranged to meet those dastardly British soldiers, whose intentions just had to be questionable, if not downright dangerous. She eventually recovered enough to send their C.O. a nice note of thanks, but it was a long, long time before Visakhians undertook that walk to Diyatalawa to see a film, however marvelous it might be.

Then there were the paper chases, otherwise known as the ‘Hares and Hounds’. These were dear to Mother’s heart. Not only were her girls learning the art of simple tracking, but they were also breathing in all that marvelous mountain air for which Bandarawela was justly famous. Writing about the ‘Bandarawela Experience’, author Manel Ratnatunga has this to say:

“But it was only the evacuation of the school to Bandarawela during the war years that brought me close to Mrs. Clara Motwani, our Principal. To all of us in those makeshift classrooms on the hills of Bandarawela, fragrant with eucalyptus and pine, she made us realize that a school could maintain high standards of learning and discipline even in makeshift buildings.

“In the dwindled school the communication gap between ‘the awesome American Principal’ and staff and students was bridged in a manner that would not have been possible in the large and impersonal Colombo buildings. With wisdom and good leadership, Mrs. Motwani altered her style to fit the countryside and keep her homesick brood well and happy.

“So there we were accompanying her on three-mile walks which had us running to keep up with her strong, long strides; visiting the rickety old cinema house atop some garage (she sometimes included the domestics, who looked askance each time there was a kiss on the screen); hitching train rides on excursions to neighbouring townships; trekking cross country over hill and dale. She was always with us, the least exhausted, and perhaps because of that day and age we never crossed the ‘Maginot line’ of respect for the Principal or our teachers. Memories of euphoria.

“For religious instruction, with no Narada Thero of Vajiraramaya Temple on call, Mrs. Motwani’s Visakhians turned to the Czechoslovakian monk, Rev. Nyanasatta, from a lonely hermitage, as he spoke English, rather than to the local monks who sometimes didn’t.”

But alas! My happy days of Dr. Ratnavale’s advised freedom were coming to an end. I was transferred to the Froebel School, also in Bandarawela, which catered mostly to foreign children. Many of the students in this school had fathers in the army and so regular bulletins were reaching us eight-year-olds from other authoritative eight-year-olds. The boys’ favourite game at Froebel was called “Bombers and Blackouts”. We girls were nurses and other unexciting helpers. My friend Suriya (Doreen Wickremasinghe’s daughter) went up to Froebel before I got there but her unusually high IQ placed her in a class or two above me.

Many wealthy Colombo citizens maintained lovely holiday homes in the hill country. The British began commandeering the best unoccupied ones on a year-round basis, for the use of their Army Officers. There was a large Army Cantonment in Diyatalawa, just three. miles from Bandarawela. Wishing to keep the British officers from taking over her upcountry bungalow, Mrs. C.V. Dias, who knew

Mother, asked if she would like to occupy “Suramya’, her beautifully appointed house, which stood on the hill the same as “Chandragiri”.

Mother was delighted and so were Su and I, for “Suramya” was delightfully luxurious. Just below “Suramya” was the holiday home of S.J.E Dias Bandaranaike and his wife Esther. They had three daughters, all of whom now entered Visakha for the duration of the war, as their old school, Bishop’s, was too far away.

Aunty Esther was an Indian, and was not only lovely to look at but also had a formidable brain … something all her three daughters inherited. The eldest, Gwen, became Principal of Bishop’s College. Sonia, who went to Cambridge for her medical degree, practices medicine in Suffolk, while Yasmine, the youngest, is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at Macquarie University in New South Wales, and has been awarded the Order of Australia for services to literature and education.

Aunty Esther had known Mother earlier, but that Bandarawela neighbourliness cemented a strong friendship. Her youngest daughter, Yasmine, became my friend and still is. Yasmine, her sisters, and I would all play Monopoly on the huge Bandaranaike antique beds which served as divans, or comfortably read books together during my holidays from Froebel. These are the memories I have of Bandarawela. These and many others.

The ‘in’ shop at Bandarawela during the war (in fact the only well-stocked one) was a branch of Colombo’s `Millers’. It pretty much catered to everyone’s needs. Our hair was cut by an elderly barber at the Bandarawela Hotel, whose clientele ranged from age three to 83. Hair styles were unheard of. We read of rationing in England, but in Ceylon no one was actually losing weight because of any constraints. In short, food was available. A locally made chocolate, ‘Barbers’, was substituted for Cadbury’s and Nestle’s – but we managed.

On one never-to-be-forgotten day, a bomb (or bombs) fell in Colombo. The girls at Visakha were in a tizzy. No work was done at all. Visakhians tried frantically to call their homes but as each call was a trunk call (which took about two hours to connect) there was little communication between them and their parents. As I remember it, I don’t think anyone was actually killed by those few bombs … but I am open to correction. Certainly, Ceylon had it good during the war.

Colombo, meanwhile, was rapidly becoming a ghost town. On the gates of half the residences of the city there were signs reading “To Let”. A house could be leased for Rs. 100/- a month, and even that was considered a luxury rental.

Back in India my father, nervous about the vulnerability of the island, soon carted his family back to the Nilgiri Hills. The story of how this came about is related later. My sister and I finished the War as pupils at the convent in Ootacamund in India, where we managed, again, to ignore the European conflict as both Father and the Indian newspapers were far more concerned with the doings of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru and the Indian Congress.

The unorthodox schooling arranged for the Bandarawela Viskhians during the war years has resulted in many tales being told. Dr. Geeta Jayalath remembers Mother tucking her into bed. She was just 10-years old. Incidentally, Geeta was one of the first Visakhians to qualify as a doctor after Mrs. Pulimood introduced the Science stream into Visakha when she succeeded Mother as Principal. Her sister Ishwari Corea, whose name is synonymous with the Public Library, remembers that Visakha-in-the-hills had no boundary walls. Students knew they should not stray out of the general periphery of the school.

One Sunday, Ishwari and a few like-minded dare-devils were merrily coasting up and down the school hill when to their dismay they ran smack into Mother, who, running true to form, was checking up on het boarders when they least expected it. Reversing themselves they sheepishly followed her up the hill. Her ‘punishment’, if it could be called that, was typical. She always explained WHY she was handing out a punishment. She did so now.

“Ishwari,” she said, “I am quite aware you were in no danger, but let us just suppose that your parents had decided to visit you, and that I was unable to find you. What could I have possibly said to them?”

A highly popular `correction’ was being asked to wait over at mealtimes for everyone else to finish. Verona Ranasinghe, one of the stricter Prefects, was constantly on the alert for little miscreants. She reported them to Mother, who tried to make the punishment fit the crime.

What Mother did not know about this particular crime-deterrent was, that the late diners got far more than those who had gone before. There was always plenty of food left over, and the extra banana, the extra slice of pineapple, even any extra caramel pudding was theirs for the asking. Mother had no idea that waiting 15 minutes for dinner was no great hardship, and she always handed out her corrective measures reluctantly. Secretly jubilant, Ishwari and her partners in crime looked so upset that Mother, who hated any disciplinary action connected with food, revoked her order.

“Never mind,” she told the little hypocrites, “I’m sure that my talk with you will of itself be enough to halt any unscheduled walks in future.”

“Oh, thank you Mrs. Motwani,” they chorused, as all that extra food evaporated before their very eyes.

Mother frequently mentioned the livelier (and therefore better remembered) girls in the boarding. Yasoma Rupasinghe was one of these, and Vinitha de Silva (now Dr. de Silva) was another.

“Her eyes literally sparkled,” Mother would say. Then there was pretty Indra de Silva, mother of the famous cricketing Wettamunis, who closely resembled the film star, Deanna Durbin. She was at that time a highly popular actress, and, was reputably Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s (president of the USA) favourite screen idol.

The Hewavitharna girls, Manel, Rani, Sita, Manthri, Kaushalya and Indira were day scholars, but they joined in most of the hostel programs. Manel was Mother’s star pupil in English. It was a talent that flowered, for Manel has become a well-known writer and is the author of many books, one of which was short listed for the Gratiaen Award.

Dhameswari Karunaratne’s parents also lived on the Visakha hill and this little academic genius went on to become the Vice Principal of Visakha after a brilliant scholastic career. She would get a near 100% in every subject, which was terribly discouraging to her classmates who, try as they might, could not retch such perfection.

There were even two boys amidst all these girls and they certainly lent colour, if not spice, to this all-girl establishment. There was no doubt in anyone’s minds that this early exposure to all female company gave these boys a head start in life, for they have both been highly successful in their chosen fields. Channa Gunasekara went on to become Sri Lanka’s Captain of cricket while Singha Basnayake ended a brilliant scholastic career working for the UNO. Lest Visakha takes all the credit I must add that both young men returned to Royal College from whence they had sprung.

There was a personal outcome of the Bandarawela days which concerned Mrs. Pulimood and myself Mrs Pulimood was the only Christian in Visakha at that time. If I happened to be home on vacation from Froebel, Mother sent me along with Mrs. Pulimood to keep her company on the walk to Church and also to fulfil Mother’s belief that all religions are worthy of being studied. As a Syrian Christian, Mrs Pulimood would explain to me that hers was the oldest organized Christian Church, dating back as it did from the arrival of St Thomas (the doubting Thomas of the Gospels) in India. I wonder if she ever realized that my subsequent deeper involvement with Christianity was the result of those first seeds sown by a brilliant teacher.

Father came to Bandarawela only once. We still went to India for holidays but for the greater part of the War, Father was on tour. He stayed put long enough to lecture for two years at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Bombay, but he kept telling Mother that she should join him in India as Ceylon’s defences were minimal. Mother would never leave Visakha until Father forced her hand as related elsewhere.

For the present, Mother continued her life as a commuting Principal. Whenever she was down in Colombo she either stayed with Dr. and Mrs. E.M. Wijerama, her close friends, or else with Dr. and Mrs. Blok whose daughter Winifred had been a pupil at Visakha. Winifred was a talented pianist. As a pianist herself, Mother loved listening to Winifred’s playing. It heightened the enjoyment of these rare social evenings of warm hospitality spent in the company of gracious friends.

Features

Banking Rules fail the elderly and informal sector

Yesterday, I received a phone call from a well-known private bank. A polite female voice on the line asked whether I was interested in obtaining a housing loan. Knowing how things typically work in the Sri Lankan banking system, I decided not to waste her time—or mine. So, I responded candidly: “I’m over 60. Are you still interested in offering your service to me?”

Yesterday, I received a phone call from a well-known private bank. A polite female voice on the line asked whether I was interested in obtaining a housing loan. Knowing how things typically work in the Sri Lankan banking system, I decided not to waste her time—or mine. So, I responded candidly: “I’m over 60. Are you still interested in offering your service to me?”

As expected, she politely replied, “No sir, we offer housing loans only to customers below the age of 60.”

Now, let’s think about this for a moment. If you’re 59 years old, does that mean the bank will give you a housing loan with just a one-year repayment period? Apparently, yes. What kind of absurd banking logic is this? Such rigid age cut-offs do not reflect risk management, but sheer bureaucratic laziness.

Banks and other financial institutions follow rules set by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. One of the main reasons for these rules is to protect the money that people deposit. Figure 1 shows one of those orders to regulate home loans provided by banks.

Employees are to provide banks with confirmation from their respective employer regarding the retirement date/age, as applicable. This requirement introduces administrative friction for the borrower and places unnecessary dependence on employer documentation. Many private sector employers do not maintain strict retirement policies, and contract-based employment has become common. Mandating employer confirmation becomes especially problematic in such cases.

Eligibility Criteria for Housing Loans Under the Terms of This Order (Effective from 10 December 2020) specify the following individuals are eligible to obtain housing loans:

Salaried Employees

* Individuals must be employed in either the public sector (e.g., government departments, state-owned enterprises) or the private sector (e.g., registered companies, private institutions).

Confirmed in Service

* The employment must be confirmed, i.e., the borrower should have completed any probationary period and be in permanent or long-term service. Probationary employees or temporary/contract workers may not be eligible under this order.

This eligibility criterion is narrow and exclusionary, especially in an evolving labour market where:

* Many skilled workers are self-employed, on a contract basis or work in the gig economy would find hard to provide evidence to prove their repayment capacity.

* Job confirmation timelines are often extended due to changing employment practices.

* Real estate investment is increasingly seen as a retirement or family-planning strategy, including among older or self-funded individuals.

While the intent may be to minimise risk for banks by ensuring repayment capacity and employment stability, this overly conservative approach may discriminate against capable, creditworthy individuals, especially older citizens or those outside traditional salaried employment structures.

Tenure of a loan

Figure 2

is an excerpt from the directive issued by CBSL, highlighting the restrictions imposed on the tenure of home loans.

Interestingly, Deshamanya Lalith Kotelawela was one of the few who had the courage—and arguably the foresight—to challenge such irrational norms. While some of his business decisions were controversial, especially the appointment of non-professionals to key financial roles, his thinking on housing loans for older customers was progressive. He proposed that housing loans should be extended even to individuals aged between 60 and 70, with repayment periods of 20 to 30 years. However, he also recommended attaching insurance to these loans—an approach that could benefit his own insurance companies. Naturally, the premiums would be significantly higher for older or higher-risk borrowers.

His reasoning was rooted in both financial logic and social realism: in most Sri Lankan families, children would never allow their parents to lose the family home. In the worst-case scenario, the property—often the most secure asset one can offer—serves as reliable collateral. From a regulatory standpoint, too, this makes sense. According to the Basel framework for banking supervision, residential mortgage loans carry a risk weight of only 50% when calculating capital adequacy. That means such loans are already considered relatively low risk.

So, why are banks clinging to these outdated, “one-size-fits-all” rules that ignore real-world dynamics, demographic shifts, and even their own financial regulations?

These are not just outdated policies—they are stupid banking rules.

Age Discrimination and Financial Exclusion

This condition is fundamentally age-based and introduces structural discrimination against older borrowers. By linking repayment tenure strictly to the borrower’s retirement date, it disproportionately excludes capable individuals nearing retirement—even if they are financially stable, have substantial savings or collateral, or have alternative income sources such as pensions, business income, or rental properties. It presumes that retirement equals financial incapacity, which is not always true in the modern economy. Today, some retired government employees receive monthly pensions exceeding Rs. 100,000.

Ignores Multigenerational and Alternative Repayment Scenarios

This policy does not account for cases where a housing loan is taken for the benefit of the family, and repayment responsibility can logically transfer to a younger family member (such as an adult child or co-borrower). In South Asian cultures especially, joint-family structures and intergenerational financial support are common. Denying long-tenure loans, based on an individual’s remaining years of employment, ignores these sociocultural realities.

Penalises Those Who Start Later

Not everyone begins salaried employment early in life. Some people shift careers, pursue entrepreneurship, or even migrate and return to salaried employment later. Under this rule, a 45-year-old starting a government job would be eligible only for a 15-year loan, regardless of income or asset base. This rigid approach fails to reflect the dynamic nature of modern work and life paths.

Common sense

Banking is often celebrated as a sector driven by logic, data, and risk mitigation. Yet, it is riddled with regulations and practices that are outdated, unempathetic, and at times, downright illogical. A prime example of this is the age discrimination embedded in housing loan policies in many Sri Lankan banks—and indeed in banks across much of the world. The author’s anecdote of receiving a call from a reputed private bank offering a housing loan, only to be told that customers over 60 are ineligible, highlights a major flaw in modern banking systems.

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental contradiction: while banks are supposed to be institutions that assess individual risk, they often make blanket decisions based on crude demographics such as age. If a person is 59 years old, they are technically eligible for a loan, but only for a tenure of one year, assuming the cut-off age is 60. That assumption, of course, is absurd. Imagine a healthy, wealthy 59-year-old customer being allowed to borrow only on terms designed for a dying man. This “stupid banking rule” lacks nuance and punishes individuals who might otherwise be low-risk borrowers with good collateral.

The Need for Reform

Age should not be the sole determinant of loan eligibility. In an era where people live longer, work well into their seventies, and often own significant assets, banking institutions must adopt more flexible, holistic credit assessment methods. Factors like health, income stability, family support, insurance coverage, and asset base must be considered alongside age.

Additionally, banks should be encouraged—or even regulated—to adopt inclusive lending practices. Policies that facilitate family-based guarantees, property-backed loans with transfer clauses, or reverse mortgage models can ensure that elderly individuals are not financially excluded.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@sliit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Trump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular

reference to Sri Lanka – Part III

(Continued from yesterday)

Textile Industry Significance

The textile and apparel sector holds outsised importance in Sri Lanka’s economy. It accounts for approximately 40% of the country’s total exports and directly employs around 350,000 workers, predominantly women from rural areas, for whom these jobs represent a crucial pathway out of poverty. When indirect employment in supporting industries is included, the sector supports the livelihoods of over one million Sri Lankans.

The industry’s development was initially facilitated through quotas assigned by the Multi-Fiber Agreement (1974-1994), which allocated specific export volumes to developing countries. When this agreement expired, Sri Lanka managed to maintain its position in global apparel supply chains by focusing on higher-value products, ethical manufacturing practices, and reliability. The country has positioned itself as a producer of quality garments, particularly lingerie, activewear, and swimwear for major global brands.

However, this success has created a structural dependency on continued access to markets in wealthy countries, particularly the United States. As the Secretary General of the Joint Apparel Association Forum, the main representative body for Sri Lanka’s

apparel and textile exporters, bluntly stated following the tariff announcement, “We have no alternate market that we can possibly target instead of the US.”

This dependency is reinforced by the industry’s integration into global supply chains dominated by U.S. brands and retailers. Many Sri Lankan factories operate on thin margins as contract manufacturers for these international companies, with limited ability to quickly pivot to new markets or product categories. The industry has also made significant investments in compliance with U.S. buyer requirements and sustainability certifications, creating path dependencies that make rapid adaptation to new market conditions extremely challenging.

The textile and apparel sector’s significance extends beyond its direct economic contributions. It has been a crucial source of foreign exchange earnings for a country that has consistently run trade deficits and struggled with external debt sustainability. In the ten years leading up to Sri Lanka’s default on external debt (2012-2021), debt repayments amounted to an average of 41% of export earnings, highlighting how vital steady export revenues are to the country’s ability to service its international obligations.

The sector has also played an important role in Sri Lanka’s social development, providing formal employment opportunities for women and contributing to poverty reduction in rural areas. Many of the industry’s workers are the primary breadwinners for their families, and their wages support extended family networks in economically disadvantaged regions of the country.

Given this context, the imposition of a 44% tariff on Sri Lankan goods, with the textile and apparel sector likely to bear the brunt of the impact, represents not merely an economic challenge but a potential social crisis for hundreds of thousands of vulnerable workers and their dependents.

SPECIFIC IMPACT OF TRUMP TARIFFS ON SRI LANKA

The imposition of a 44% tariff on Sri Lankan exports to the United States represents a seismic shock to an economy still recovering from its worst crisis in decades. This section examines the immediate economic consequences, the implications for Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability, and the broader social and political ramifications of this dramatic policy shift.

Immediate Economic Consequences

The most immediate impact of President Trump’s tariffs will be a severe erosion of Sri Lankan goods’ competitiveness in the U.S. market. A 44% price increase effectively prices many Sri Lankan products out of reach for American consumers and businesses, particularly in price-sensitive categories like apparel, where margins are already thin and competition from other producing countries is intense.

Economic analysts project significant declines in export volumes as a result. The PublicFinance.lk think tank estimates that the new tariff rates will lead to a 20% fall in exports to America and an annual loss of approximately $300 million in foreign exchange earnings. Given that Sri Lanka’s total merchandise exports in 2024 were around $13 billion, this represents a substantial blow to the country’s trade balance and economic growth prospects.

The textile and apparel sector will bear the brunt of this impact. Industry representatives have warned that numerous factories may be forced to reduce production or close entirely if they cannot quickly find alternative markets for their products. The Joint Apparel Association Forum has indicated that smaller manufacturers with less diversified customer bases and limited financial reserves will be particularly vulnerable to closure.

These production cutbacks and potential closures would translate directly into job losses. Conservative estimates suggest that tens of thousands of workers in the textile sector could lose their livelihoods if the tariffs remain in place for an extended period. Given that many of these workers are women from rural areas with limited alternative employment opportunities, the social impact of these job losses would be particularly severe.

Beyond the direct effects on textile exports, the tariffs will have ripple effects throughout Sri Lanka’s economy. Supporting industries such as packaging, logistics, and input suppliers will face reduced demand. The loss of foreign exchange earnings will put pressure on the Sri Lankan rupee, potentially leading to currency depreciation that would increase the cost of essential imports including fuel, food, and medicine.

The timing of these tariffs is especially problematic given Sri Lanka’s fragile economic recovery. After experiencing a GDP contraction of 7.8% in 2022 during the height of the economic crisis, the country had only recently returned to modest growth. The IMF had projected GDP growth of 3.1% for 2025, but this forecast now appears overly optimistic in light of the tariff shock. Some economists are already revising their growth projections downward, with some suggesting growth could fall below 2% if the full impact of the tariffs materializes. We must hope they will be proven wrong.

Impact on Sri Lanka’s Debt Sustainability

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of Trump’s tariffs is their potential to undermine Sri Lanka’s hard-won progress on debt sustainability. After defaulting on its external debt in April 2022, the country has undergone a painful restructuring process that concluded only in December 2024. This restructuring was predicated on assumptions about Sri Lanka’s future ability to generate foreign exchange to service its remaining debt obligations.

The IMF’s debt sustainability analysis, which formed the basis for the restructuring agreement, focused almost exclusively on debt as a share of GDP while making insufficient distinction between domestic and foreign debt. This approach has been criticized for ignoring the structural trade deficit and the critical importance of foreign currency earnings to Sri Lanka’s ability to meet its external obligations.

The $300 million annual reduction in export earnings projected as a result of the tariffs directly threatens these calculations. Sri Lanka’s external debt stood at approximately $55 billion in 2023 (about 65% of its GDP), and even after restructuring, debt service payments will consume a significant portion of the country’s foreign exchange earnings in coming years.

In the decade preceding Sri Lanka’s default (2012-2021), debt repayments consumed an average of 41% of export earnings, an unsustainably high ratio that contributed directly to the eventual crisis. The loss of export revenues due to President Trump’s tariffs risks pushing this ratio back toward dangerous levels, potentially setting the stage for renewed debt distress despite the recent restructuring.

This situation highlights a fundamental flaw in the approach taken by international financial institutions to debt sustainability in developing countries. Unlike the treatment afforded to West Germany through the London Debt Agreement of 1953, where future debt repayments were explicitly linked to the country’s trade surplus and capped at 3% of export earnings—Sri Lanka and similar countries are expected to meet rigid repayment schedules regardless of their trade performance or external shocks beyond their control.

The tariffs thus expose the precariousness of Sri Lanka’s economic recovery and the fragility of the international debt architecture that underpins it. Without significant adjustments to account for this external shock, the country could find itself sliding back toward debt distress despite all the sacrifices made by its people during the recent adjustment period.

Social and Political Implications

The economic consequences of Trump’s tariffs will inevitably translate into social and political challenges for Sri Lanka. The country has already experienced significant social strain due to the austerity measures implemented under the IMF program, including tax increases, subsidy reductions, and public sector wage restraint. The additional economic pain caused by export losses and job cuts risks exacerbating social tensions and potentially triggering renewed protests.

The textile industry’s workforce is predominantly female, with many workers supporting extended family networks. Job losses in this sector would therefore have disproportionate impacts on women’s economic empowerment and household welfare, potentially reversing progress on gender equality and poverty reduction. Many of these workers come from rural areas where alternative formal employment opportunities are scarce, raising the spectre of increased rural poverty and potential migration pressures.

Politically, the tariff shock presents a significant challenge for President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s government, which came to power promising economic revival and relief from the hardships of the crisis period. The administration has appointed an advisory committee consisting of government officials and private sector representatives to study the impact of the tariffs and develop response strategies, but its options are constrained by limited fiscal space and the conditions of the IMF programme.

The situation also raises questions about Sri Lanka’s foreign policy orientation. The country has traditionally maintained balanced relationships with major powers, including the United States, China, and India. However, the unilateral imposition of punitive tariffs by the United States may prompt some policymakers to reconsider this balance and potentially look more favourably on economic engagement with China, which has been a major infrastructure investor in Sri Lanka through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Such a reorientation would have significant geopolitical implications in the Indian Ocean region, where great power competition has intensified in recent years. It could potentially accelerate the fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, a trend that President Trump’s broader tariff policy seems designed to encourage despite its economic costs.

The social and political fallout from the tariffs thus extends far beyond immediate economic indicators, potentially reshaping Sri Lanka’s development trajectory and its place in the regional and global order. For a country still recovering from political instability triggered by economic crisis, these additional pressures come at a particularly vulnerable moment.

BROADER IMPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPING ECONOMIES

Sri Lanka’s experience with Trump’s tariffs is not unique. The sweeping nature of these trade measures has created similar challenges for developing economies across the Global South, revealing structural vulnerabilities in the international economic system and raising fundamental questions about the sustainability of export-led development models in an era of rising protectionism.

Comparative Analysis with Other Affected Developing Countries

While Sri Lanka faces a punishing 44% tariff rate, it is not alone in confronting severe trade barriers. Bangladesh, another South Asian country heavily dependent on textile exports, has been hit with a 37% tariff. Like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh has built its development strategy around its garment industry, which accounts for more than 80% of its export earnings and employs approximately 4 million workers, mostly women.

Other significantly affected developing economies include Vietnam (46% tariff), Cambodia (49%), Pakistan (29%), and several African nations that had previously benefited from preferential access to the U.S. market through programs like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Many of these countries share common characteristics, relatively low per capita incomes, heavy reliance on a narrow range of export products, and limited domestic markets that make export-oriented growth their primary development pathway.

The pattern of tariff rates reveals a troubling dynamic, some of the highest tariffs have been imposed on countries that can least afford the economic shock. While wealthy nations like Japan or Germany certainly face challenges from these trade

barriers, they possess diversified economies, substantial domestic markets, and financial resources to cushion the impact. By contrast, countries like Sri Lanka or Bangladesh have far fewer economic buffers and face potentially devastating consequences from similar or higher tariff rates.

This disparity highlights how President Trump’s “reciprocal tariff” formula, ostensibly designed to create a level playing field, actually reinforces existing power imbalances in the global economy. By treating trade deficits as the primary metric for determining tariff rates, the policy ignores the vast differences in economic development, productive capacity, and financial resilience between countries at different stages of development.

Structural Vulnerabilities of Export-Dependent Economies

The tariff shock has exposed fundamental vulnerabilities in the export-led development model that has dominated economic thinking about the Global South for decades. Since the 1980s, international financial institutions have consistently advised developing countries to orient their economies toward export markets, specialize according to comparative advantage, and integrate into global value chains as a path to economic growth and poverty reduction.

This model has delivered significant benefits in many cases. Countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and, to some extent, Sri Lanka have achieved impressive poverty reduction and economic growth by expanding their manufacturing exports. However, President Trump’s tariffs reveal the precariousness of development strategies built on continued access to wealthy consumer markets, particularly the United States.

Several structural vulnerabilities have become apparent,

1. First, export concentration creates acute dependency on a small number of markets and products. When Sri Lanka sends 23% of its exports to the United States and concentrates 40% of its total exports in textiles and apparel, it becomes extraordinarily vulnerable to policy changes affecting that specific market-product combination.

Diversification, both of export markets and products, has often been acknowledged as desirable in theory but has proven difficult to implement in practice due to established trade patterns, buyer relationships, and specialized production capabilities.

2. Second, participation in global value chains often traps developing countries in lower-value segments of production with limited opportunities for upgrading. Sri Lanka’s textile industry, while more advanced than some of its regional competitors, still primarily engages in contract manufacturing rather than controlling higher-value activities like design, branding, or retail. This position in the value chain yields lower returns and creates dependency on decisions made by lead firms in wealthy countries.

3. Third, the mobility of capital relative to labour creates a fundamental power imbalance. If tariffs make production in Sri Lanka uneconomical, global brands can relatively quickly shift their sourcing to other countries with lower tariffs or costs. However, Sri Lankan workers cannot similarly relocate, leaving them bearing the brunt of adjustment costs through unemployment and wage depression.

4. Fourth, developing countries typically lack the fiscal space to provide adequate social protection during economic shocks. Unlike wealthy nations that can deploy extensive safety nets during trade disruptions, countries like Sri Lanka, already implementing austerity measures under IMF programmes, have limited capacity to support displaced workers or affected industries. This exacerbates the social costs of trade shocks and can trigger political instability. (To be continued)

(The writer served as the Minister of Justice, Finance and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka)

Disclaimer:

This article contains projections and scenario-based analysis based on current economic trends, policy statements, and historical behaviour patterns. While every effort has been made to ensure factual accuracy, using publicly available data and established economic models, certain details, particularly regarding future policy decisions and their impacts, remain hypothetical. These projections are intended to inform discussion and analysis, not to predict outcomes with certainty.

Features

Opportunity for govt. to confirm its commitment to reconciliation

by Jehan Perera

The international system, built at the end of two world wars, was designed with the aspiration of preserving global peace, promoting justice, and ensuring stability through a Rules-Based International Order. Institutions such as the United Nations, the UN Covenants on Human Rights and the United Nations Human Rights Council formed the backbone of this system. They served as crucial platforms for upholding human rights norms and international law. Despite its many imperfections, this system remains important for small countries like Sri Lanka, offering some measure of protection against the pressures of great power politics. However, this international order has not been free from criticism. The selective application of international norms, particularly by powerful Western states, has weakened its legitimacy over time.

The practice of double standards, with swift action in some conflicts like Ukraine but inaction in others like Palestine has created a credibility gap, particularly among non-Western countries. Nevertheless, the core ideals underpinning the UN system such as justice, equality, and peace remain worthy of striving towards, especially for countries like Sri Lanka seeking to consolidate national reconciliation and sustainable development. Sri Lanka’s post-war engagement with the UNHRC highlights the tensions between sovereignty and accountability. Following the end of its three-decade civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka faced multiple UNHRC resolutions calling for transitional justice, accountability for human rights abuses, and political reforms. In 2015, under Resolution 30/1, Sri Lanka co-sponsored a landmark commitment to implement a comprehensive transitional justice framework, including truth-seeking, reparations, and institutional reforms.

However, the implementation of these pledges has been slow and uneven. By 2019, Sri Lanka formally withdrew its support for UNHRC Resolution 30/1, citing concerns over sovereignty and external interference. This has led to a deepening cycle with more demanding UNHRC resolutions being passed at regular intervals, broadening the scope of international scrutiny to the satisfaction of the minority, while resistance to it grows in the majority community. The recent Resolution 51/1 of 2022 reflects this trend, with a wider range of recommendations including setting up of an external monitoring mechanism in Geneva. Sri Lanka today stands at a critical juncture. A new government, unburdened by direct involvement in past violations and committed to principles of equality and inclusive governance, now holds office. This provides an unprecedented opportunity to break free from the cycle of resolutions and negative international attention that have affected the country’s image.

KEEPING GSP+

The NPP government has emphasised its commitment to treating all citizens equally, regardless of ethnicity, religion, or region. This commitment corresponds with the spirit of the UN system, which seeks not to punish but to promote positive change. It is therefore in Sri Lanka’s national interest to approach the UNHRC not as an adversary, but as a partner in a shared journey toward justice and reconciliation. Sri Lanka must also approach this engagement with an understanding of the shortcomings of the present international system. The West’s selective enforcement of human rights norms has bred distrust. Sri Lanka’s legitimate concerns about double standards are valid, particularly when one compares the Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with the muted responses to the plight of Palestinians or interventions in Libya and Iraq.

However, pointing to hypocrisy does not absolve Sri Lanka of its own obligations. Indeed, the more credible and consistent Sri Lanka is in upholding human rights at home, the stronger its moral position becomes in calling for a fairer and more equitable international order. Engaging with the UN system from a position of integrity will also strengthen Sri Lanka’s international partnerships, preserve crucial economic benefits such as GSP Plus with the European Union, and promote much-needed foreign investment and tourism. The continuation of GSP Plus is contingent upon Sri Lanka’s adherence to 27 international conventions relating to human rights, labour rights, environmental standards, and good governance. The upcoming visit of an EU monitoring mission is a vital opportunity for Sri Lanka to demonstrate its commitment to these standards. It needs to be kept in mind that Sri Lanka lost GSP Plus in 2010 due to concerns over human rights violations. Although it was regained in 2017, doubts were raised again in 2021, when the European Parliament called for its reassessment, citing the continued existence and use of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and broader concerns about rule of law.

The government needs to treat the GSP Plus obligations with the same seriousness that it applies to its commitments to the International Monetary Fund. Prior to the elections, the NPP pledged to repeal the PTA if it came to power. There are some cases reported from the east where trespass of forest had been stated as offences and legal action filed under the PTA in courts which had been dragging for years, awaiting instructions from the Attorney General which do not come perhaps due to over-work. But the price paid by those detained under this draconian law is unbearably high. The repeal or substantial reform of the PTA is urgent, not only to meet human rights standards but also to reassure the EU of Sri Lanka’s sincerity. The government has set up a committee to prepare new legislation. The government needs to present the visiting EU delegation with a credible and transparent roadmap for reform, backed by concrete actions rather than promises. Demonstrating goodwill at this juncture will not only preserve GSP Plus but also strengthen Sri Lanka’s hand in future trade negotiations and diplomatic engagements.

INTERNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP

The government’s recent emphasis on good governance, economic recovery, and anti-corruption is a positive foundation. But as experience shows, economic reform alone is insufficient. Political reforms, especially those that address the grievances of minority communities and uphold human rights, are equally critical to national stability and prosperity. There is a recent tendency of the state to ignore these in reality and announce that there is no minority or majority as all are citizens, but which is seen by the minorities as sweeping many issues under the carpet.

Examples give are the appointment of large number of persons from the majority community to the council of Eastern University whose faculty is mainly from the minority communities or the failure to have minority representation in many high level state committees. Neglecting these dimensions risks perpetuating internal divisions and giving ammunition to external critics. The government’s political will needs to extend beyond economic management to genuine national reconciliation. Instead of being seen as a burden, meeting the EU’s GSP Plus obligations and those of UNHRC Resolution 51/1 can be viewed as providing a roadmap.

The task before the government is to select key areas where tangible progress can be made within the current political and institutional context, demonstrating good faith and building international confidence. Several recommendations within Resolution 51/1 can be realistically implemented without compromising national sovereignty. Advancing the search for truth and providing reparations to victims of the conflict, repealing the Prevention of Terrorism Act, revitalising devolution both by empowering the elected provincial councils, reducing the arbitrary powers of the governors as well as through holding long-delayed elections are all feasible and impactful measures. The return of occupied lands, compensation for victims, and the inclusion of minority communities in governance at all levels are also steps that are achievable within Sri Lanka’s constitutional framework and political reality. Crucially, while engaging with these UNHRC recommendations, the government needs to also articulate its own vision of reconciliation and justice. Rather than appearing as if it is merely responding to external pressure, the government should proactively frame its efforts as part of a homegrown agenda for national renewal. Doing so would preserve national dignity while demonstrating international responsibility.

The NPP government is unburdened by complicity in past abuses and propelled by a mandate for change. It has a rare window of opportunity. By moving decisively to implement assurances given in the past to the EU to safeguard GSP Plus and engaging sincerely with the UNHRC, Sri Lanka can finally extricate itself from the cycle of international censure and chart a new path based on reconciliation and international partnership. As the erosion of the international rules-based order continues and big power rivalries intensify, smaller states like Sri Lanka need to secure their positions through partnerships, and multilateral engagement. In a transactional world, in which nothing is given for free but everything is based on give and take, trust matters more than ever. By demonstrating its commitment to human rights, reconciliation, and inclusive governance, not only to satisfy the international community but also for better governance and to develop trust internally, Sri Lanka can strengthen its hand internationally and secure a more stable and prosperous future.

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoPick My Pet wins Best Pet Boarding and Grooming Facilitator award

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNew Lankan HC to Australia assumes duties

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoJapan-funded anti-corruption project launched again

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLankan ‘snow-white’ monkeys become a magnet for tourists

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoKing Donald and the executive presidency

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoACHE Honoured as best institute for American-standard education

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Truth will set us free – I

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNational Savings Bank appoints Ajith Akmeemana,Chief Financial Officer