Features

The Absence of a Desired Image – a tour de force

by Seneka Abeyratne

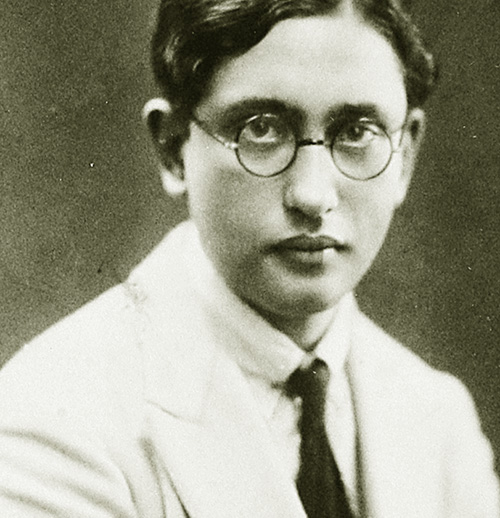

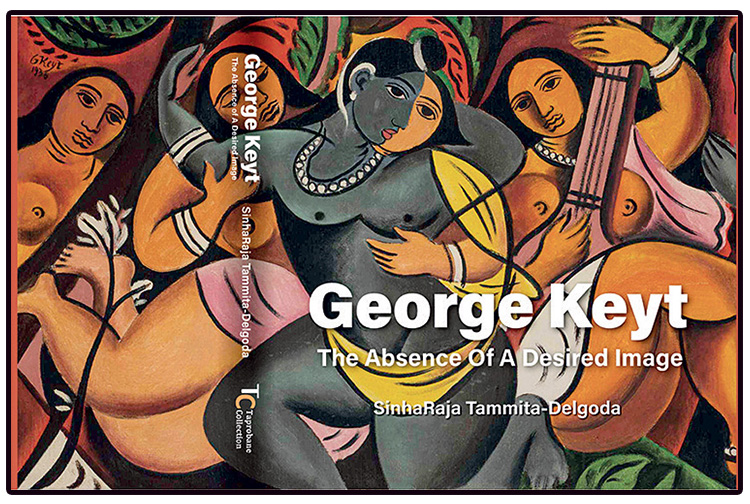

Dr SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda’s new art history book, “George Keyt – The Absence of a Desired Image,” provides fascinating insights into the life and work of Sri Lanka’s greatest artist. The book, published by the Taprobane Collection, is 464 pages long from cover to cover with the Appendices (expertly compiled by Uditha Devapriya) comprising about 90 pages. A hefty piece of non-fiction, it is skillfully crafted with meticulous attention paid to detail. Tammita Delgoda has produced a work of art – a tour de force that grips the reader and captures the imagination like an epic novel. Thanks to the author’s breezy writing style and great zest for story-telling, it moves at a brisk pace and takes us on an unforgettable journey. The book’s design is exquisite, especially in respect of the delicate interplay between stylish narrative and ravishing visual imagery.

The book could be viewed as a marvelous tapestry of the painter’s journey through life created by a master craftsman. We discover that not only was Keyt a great, self-taught artist but a brilliant poet, scholar, and linguist as well. How a single individual could excel in so many different fields is something to behold. Here was someone who danced ecstatically to the music of his soul.

Keyt died at the age of 92 and his life spanned all ten decades of the previous century. Though he was playful in his youth, he became a studious and serious-minded individual after leaving school. As The Absence of a Desired Image demonstrates, in terms of range and versatility, Keyt’s artistic and literary output was phenomenal. The book has 18 engrossing chapters plus a lucid Introduction that contains a compact literature review. It is worthwhile noting that several eminent authors have written books on George Keyt including the Indian art historian, critic and curator, Yasodhara Dalmia, whose book is entitled, Life and Times of George Keyt (2017).

Tammita-Delgoda does an excellent job in revealing the multifaceted nature of Keyt’s personality as well as his work. Though Keyt the painter is the central theme of his book, there are several sub-themes, such as Keyt the poet, Keyt the scholar, Keyt the writer, Keyt the translator, and Keyt the illustrator, which also receive close attention. Arguably, The Absence of a Desired Image goes further than any other book on Keyt in terms of weaving the man and his work into a composite whole.

An attractive feature of this weighty tome is that Keyt’s life is interwoven with Sri Lanka’s history, culture, and social fabric. We learn a great deal not only about Keyt’s family background and personal life, but also about how two great religions – Buddhism and Hinduism – influenced his work and his mindset. Keyt was a Burgher and so was his closest friend, Lionel Wendt – Sri Lanka’s greatest photographer. Accordingly, the book’s observations on and impressions of the Burgher community in the first half of the 20th century are highly pertinent to the overarching theme – Keyt the painter.

Because India and Keyt’s life were inextricably linked, the book provides a comprehensive account of how Indian culture influenced Keyt and vice versa. The adroit manner in which it captures the shades and nuances of this synergistic interaction is laudable. But if Keyt ultimately turned to cubism and gave it a distinct Sri Lankan flavor, it was largely due to the influence of Picasso, an artist that he deeply revered.

The focus of Chapter I is the impact that Sri Lanka’s transition from British colonial rule to self-rule had on Keyt’s life. “Confronted with the turmoil of Independent Sri Lanka, Keyt deliberately withdrew into a private world of idyllic romance, divine fantasy and literary symbolism.”

Chapter II contains a fine description of Keyt’s formative years at Trinity College, where students were encouraged to develop their creative, intellectual and artistic skills. Though Keyt never passed any exams, he did win the College Art Prize at age fourteen. And he began to read and write poetry.

In Chapter III we learn how Keyt began studying Buddhism and Pali after leaving school. The Keyt family lived near the Malwatte Vihara, overlooking Kandy Lake, and the scholar monk and poet, Ven. Pinnawela Dheerananda, became Keyt’s mentor.

Chapter IV tells us that when Keyt began to paint, his initial focus was the rhythms and routines of life in Buddhist temples. Meanwhile, he produced many essays and illustrations for various magazines. “His first major literary work was entitled Poetry from the Sinhalese (1938).”

Chapter V indicates that his career as an artist began to take off in his late twenties. “Keyt’s early paintings depicted the landscape and people of Kandy. Naturalistic and representative, they are very carefully structured and solidly organized …” If he was not painting, he was writing poetry. He published several poems in the 1930s, including Image in Absence.

The painter married Ruth Jansz in 1930 by whom he had two daughters. Though Ruth was a devoted wife and mother, Keyt was unfaithful to her, and their marriage broke down before the decade ended. He was in love with Lucia, his daughter’s nanny. Abandoning his family, he went to live with Lucia in her village, Pilawela. Lucia (also known as Pilawela Menike) took good care of him and bore him two sons. The couple relocated several times and eventually made Sirimalwatte (a village in Kandy) their home in 1950.

As explained in Chapter VI, “George Keyt was the first contemporary painter to derive inspiration from the wellspring of Sri Lanka’s ancient tradition.” By carefully studying the Sigiriya frescoes, he mastered the art of drawing the vaka deka, double curve. In the 1930s he began to abandon naturalism and representation in favor of the curving line. From then on, sweeping curves and counter curves became a prominent feature of his work. “Two women, painted during the 1930s, shows how integral the curving line was to Keyt’s work …”

The culture of Polonnaruwa during the Middle Ages was an amalgam of Buddhism and Hinduism and Keyt was profoundly influenced by the bronze images of Hindu deities produced by the cholas. “The heads of many of Keyt’s figures, both male and female, were inspired by the Polonnaruwa bronzes. Abstracted and sharply drawn, with their long faces, pointed noses and heavy lidded eyes, many of them resemble Shiva and Parvati.” Examples of Keyt’s paintings that demonstrate these stylized features are Nayika and The Flutist.

Keyt had in-depth knowledge of Kandyan Buddhist art. “Ian Goonetileke notes that the wall paintings of Kandy were a major factor in the artistic language which Keyt evolved for himself.” For example, Gotaimbara closely resembles a Kandyan mural in style, form and color scheme.

Chapter VII , written with verve and sensitivity, is about Keyt and his best friend – the pianist, photographer, critic and cinematographer, Lionel Wendt. If Wendt opened Keyt’s eyes to the world of modernism, Keyt introduced Wendt to the world of Kandyan dance.

Chapter VIII provides a cogent analysis of Keyt’s Kandyan village paintings such as Ploughing, Harvest, Man with Bull, Woman with Parasol, Fruit Seller in respect of style, form, color, and thematic content. It also elaborates upon Keyt’s fascination with Kandyan dance. “Over the years, Keyt became deeply versed in the arts and drumming. His essay, Kandyan Dancing (1953), provides a comprehensive introduction to the world of Sinhala dance.”

As elucidated in Chapter IX, it was through the books, journals and magazines that Lionel Wendt shared with Keyt that the latter discovered modernism. Of these, the most important was Cahiers d’Art, which showcased the work of leading European modern artists. “Keyt’s discovery of cubism caused him to discard the art of representation. By the 1930s his style had changed. Like Picasso, he combined distortion with bold outline. Using crisp, heavy lines, he made the continuing line a defining feature, merging and fusing figures together.” The influence of other European modern artists such as Léger, Braque, Derain and Matisse can also be observed in his work. For example, Matisse’s Odalisque (1920-21) inspired Keyt to paint Reclining Woman almost fifty years later.

Chapter X provides useful information on the formation of the Ceylon Society of Arts as well as the 1943 Group consisting of prominent artists excluded by the Ceylon Society, including Ivan Peries, George Keyt, Justin Daraniyagala, and Harry Peiris. The idea for the establishment of this Group came from Ivan Peries and was executed by Lionel Wendt. “The 43 Group became Asia’s first modern art movement. For Lionel Wendt it was a great moment of fulfillment which embodied the climax of his artistic career …”

From Chapter XI we learn the 43 Group became famous due to its authentic blend of traditional forms with modern Western influence. “In the years which followed Independence, the 43 Group held a series of regular exhibitions which gradually established modern art in Sri Lanka. By the early fifties, the 43 Group was winning international acclaim and showing its work in Europe.” Keyt’s good friend, Ian Goonetileke (a well-known scholar and bibliographer,), observed that though the core members of the 43 Group were highly gifted, they were not genuinely rooted in their culture, which is why the Group disintegrated in the late sixties. But as this book points out, the only exception was George Keyt.

“Crossing the boundaries of alienation, Keyt was able to find a new truth and forge a relationship with his environment. This endowed his work with the enduring relevance which exists to this day.”

Chapter XII provides a fascinating account of how Keyt became more and more “Indian” in respect of his mindset as well as his art. After his first visit to India in 1939, he kept going back. In 2021 Tammita-Delgoda interviewed Keyt’s elder daughter, Diana Keyt, who said: “Once he went to India, he changed and converted to Hinduism. He became a follower of Krishna. Hinduism came to exercise a bigger influence on him. In the end it won over Buddhism.” The painter lived in India from 1946 to 1949.

Ratikeli is a fine example of a Keyt painting inspired by Hindu mythology. The two great Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabarata, also had a profound impact on his work. This chapter demonstrates with the assistance of drawings and paintings the significant extent to which the painter was also inspired by Indian art, sculpture, music, and dancing.

One of the most nostalgic sections in this book is Chapter XIII, where the Indian factor continues to receive attention. Keyt’s circle of friends during his three-year stay in India (1946-49) included Mulk Raj Anand, Minette de Silva, and her sister Marcia (Anil). From 1946 to 1948, Anil was the assistant editor and Minette, the architectural editor of Marg. During this time Lionel Wendt, Geoge Keyt, and the 43 Group as a whole figured prominently in this prestigious magazine.

The trio (Anand and the de Silva sisters) were the chief organizers of Keyt’s first ever solo international exhibition at the Convocation Hall in Bombay in 1947. The exhibition, which featured 64 paintings as well as a comprehensive catalogue, was lauded by both Indian and foreign critics. “What resonated most was the way in which Keyt had absorbed and depicted the Indian heritage.” According to his biographer, Martin Russel (as per his book, George Keyt) as well as the art historian William Archer (as per his book, India and Modern Art), Keyt’s contribution to the evolution of modern art in India was seminal. (Both authors, by the way, were British.)

In 1947 Keyt published an illustrated version of Gita Govinda, an epic poem recounting the loves of Radha and Krishna which he had rendered from the Sanskrit. “Directly linked to Keyt’s portrayal of love, it became the subject for some of his most powerful erotic paintings.” A notable example, in this regard, is Rasa Lila, the Dance of Divine Love. Keyt, incidentally, had a passionate affair with one Barbara Smith – “an attractive and sophisticated woman of Anglo-Indian descent.” A well-known editor with the Oxford University Press, she was based in Bombay.

As per Chapter XIV, the exhibition at the Convocation Hall opened many other doors for this preeminent Sri Lankan artist. His solo exhibition in New Delhi in 1952, which featured 72 paintings, was a great success. “In the years since Bombay, Keyt’s work had become embedded in the Indian consciousness. In new Delhi he was hailed as a product of the Indian tradition.” Mulk Raj Anand’s The Story of India (1948) and well as A.S. Raman’s Tales from Indian Mythology (1961) were illustrated by Keyt. We note that though the two authors were Indian, the illustrator was Sri Lankan.

In Chapter XV we return to Sirimalwatte and to Keyt’s work based on rural life and Sinhalese traditions, culture and folklore. “In much the same way as he had done with his great murals at the Gotami Vihare, Keyt brought the classical inheritance of the country in visual form.” The use of acrylics from the seventies onwards made his colors much brighter and augmented the decorative beauty of his paintings.

During the second half of the 20th century his paintings found buyers in every part of the world and his work was featured in numerous foreign journals, magazines, and newspapers. “He had become famous, a national and international celebrity.” He held several solo exhibitions in Sri Lanka and India and three in London as well. In 1977 he was honored with a special Felicitation Volume to mark his 75th birthday and in 1988, the George Keyt Foundation was established to promote and publicize his work.

We note from Chapters XVI and XVII that female nudity, lesbianism, and unbridled sexuality are the central, interlocking themes in a significant number of Keyt’s paintings. “At the core of his treatment is the line and curve. Key’s mastery of the curving line enables him to create sweeping, all engrossing curves which capture the lush sexuality of a woman’s body. With the curve as his foundation, Keyt combines line with rhythm, evolving a rhythmic line of his very own.” In this regard, Lovers – an acrylic painting depicting a lesbian couple – is one of his most stylish works.

Chapter XVIII, the most poignant section in the book, is where we learn that Keyt eventually left his second wife for a young Indian woman, Kusum Narayan, whom he married in 1973 by converting to Islam. The couple actually stayed in Sirimalwatte for a while before moving to the Western Province. The cities they lived in included Nugegoda and Galle. In 1992, they returned to Sirimalwatte and Pinawela Menike graciously accepted them. Keyt’s health began to deteriorate and his life came to an end in July 1993. This great modern artist, who was fondly known as the Asian Picasso, was so highly regarded in his homeland that he was given a state funeral in Colombo.

The Appendices are breathtaking, especially the Plates section where paintings, drawings and other works by Keyt are featured for the first time in any formal publication. It is truly the icing on the cake.

“George Keyt: Absence of a Desired Image” is available for sale at leading bookstores across the country. For details on direct purchases of the book, you can contact the publishers, Taprobane Collection, at shamilp54@gmail.com.

Features

Freedom for giants: What Udawalawe really tells about human–elephant conflict

If elephants are truly to be given “freedom” in Udawalawe, the solution is not simply to open gates or redraw park boundaries. The map itself tells the real story — a story of shrinking habitats, broken corridors, and more than a decade of silent but relentless ecological destruction.

“Look at Udawalawe today and compare it with satellite maps from ten years ago,” says Sameera Weerathunga, one of Sri Lanka’s most consistent and vocal elephant conservation activists. “You don’t need complicated science. You can literally see what we have done to them.”

What we commonly describe as the human–elephant conflict (HEC) is, in reality, a land-use conflict driven by development policies that ignore ecological realities. Elephants are not invading villages; villages, farms, highways and megaprojects have steadily invaded elephant landscapes.

Udawalawe: From Landscape to Island

Udawalawe National Park was once part of a vast ecological network connecting the southern dry zone to the central highlands and eastern forests. Elephants moved freely between Udawalawe, Lunugamvehera, Bundala, Gal Oya and even parts of the Walawe river basin, following seasonal water and food availability.

Today, Udawalawe appears on the map as a shrinking green island surrounded by human settlements, monoculture plantations, reservoirs, electric fences and asphalt.

“For elephants, Udawalawe is like a prison surrounded by invisible walls,” Sameera explains. “We expect animals that evolved to roam hundreds of square nationakilometres to survive inside a box created by humans.”

Elephants are ecosystem engineers. They shape forests by dispersing seeds, opening pathways, and regulating vegetation. Their survival depends on movement — not containment. But in Udawalawa, movement is precisely what has been taken away.

Over the past decade, ancient elephant corridors have been blocked or erased by:

Irrigation and agricultural expansion

Tourism resorts and safari infrastructure

New roads, highways and power lines

Human settlements inside former forest reserves

“The destruction didn’t happen overnight,” Sameera says. “It happened project by project, fence by fence, without anyone looking at the cumulative impact.”

The Illusion of Protection

Sri Lanka prides itself on its protected area network. Yet most national parks function as ecological islands rather than connected systems.

“We think declaring land as a ‘national park’ is enough,” Sameera argues. “But protection without connectivity is just slow extinction.”

Udawalawe currently holds far more elephants than it can sustainably support. The result is habitat degradation inside the park, increased competition for resources, and escalating conflict along the boundaries.

“When elephants cannot move naturally, they turn to crops, tanks and villages,” Sameera says. “And then we blame the elephant for being a problem.”

The Other Side of the Map: Wanni and Hambantota

Sameera often points to the irony visible on the very same map. While elephants are squeezed into overcrowded parks in the south, large landscapes remain in the Wanni, parts of Hambantota and the eastern dry zone where elephant density is naturally lower and ecological space still exists.

“We keep talking about Udawalawe as if it’s the only place elephants exist,” he says. “But the real question is why we are not restoring and reconnecting landscapes elsewhere.”

The Hambantota MER (Managed Elephant Reserve), for instance, was originally designed as a landscape-level solution. The idea was not to trap elephants inside fences, but to manage land use so that people and elephants could coexist through zoning, seasonal access, and corridor protection.

“But what happened?” Sameera asks. “Instead of managing land, we managed elephants. We translocated them, fenced them, chased them, tranquilised them. And the conflict only got worse.”

The Failure of Translocation

For decades, Sri Lanka relied heavily on elephant translocation as a conflict management tool. Hundreds of elephants were captured from conflict zones and released into national parks like Udawalawa, Yala and Wilpattu.

The logic was simple: remove the elephant, remove the problem.

The reality was tragic.

“Most translocated elephants try to return home,” Sameera explains. “They walk hundreds of kilometres, crossing highways, railway lines and villages. Many die from exhaustion, accidents or gunshots. Others become even more aggressive.”

Scientific studies now confirm what conservationists warned from the beginning: translocation increases stress, mortality, and conflict. Displaced elephants often lose social structures, familiar landscapes, and access to traditional water sources.

“You cannot solve a spatial problem with a transport solution,” Sameera says bluntly.

In many cases, the same elephant is captured and moved multiple times — a process that only deepens trauma and behavioural change.

Freedom Is Not About Removing Fences

The popular slogan “give elephants freedom” has become emotionally powerful but scientifically misleading. Elephants do not need symbolic freedom; they need functional landscapes.

Real solutions lie in:

Restoring elephant corridors

Preventing development in key migratory routes

Creating buffer zones with elephant-friendly crops

Community-based land-use planning

Landscape-level conservation instead of park-based thinking

“We must stop treating national parks like wildlife prisons and villages like war zones,” Sameera insists. “The real battlefield is land policy.”

Electric fences, for instance, are often promoted as a solution. But fences merely shift conflict from one village to another.

“A fence does not create peace,” Sameera says. “It just moves the problem down the line.”

A Crisis Created by Humans

Sri Lanka loses more than 400 elephants and nearly 100 humans every year due to HEC — one of the highest rates globally.

Yet Sameera refuses to call it a wildlife problem.

“This is a human-created crisis,” he says. “Elephants are only responding to what we’ve done to their world.”

From expressways cutting through forests to solar farms replacing scrublands, development continues without ecological memory or long-term planning.

“We plan five-year political cycles,” Sameera notes. “Elephants plan in centuries.”

The tragedy is not just ecological. It is moral.

“We are destroying a species that is central to our culture, religion, tourism and identity,” Sameera says. “And then we act surprised when they fight back.”

The Question We Avoid Asking

If Udawalawe is overcrowded, if Yala is saturated, if Wilpattu is bursting — then the real question is not where to put elephants.

The real question is: Where have we left space for wildness in Sri Lanka?

Sameera believes the future lies not in more fences or more parks, but in reimagining land itself.

“Conservation cannot survive as an island inside a development ocean,” he says. “Either we redesign Sri Lanka to include elephants, or one day we’ll only see them in logos, statues and children’s books.”

And the map will show nothing but empty green patches — places where giants once walked, and humans chose. roads instead.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

Features

When the Wetland spoke after dusk

By Ifham Nizam

As the sun softened over Colombo and the city’s familiar noise began to loosen its grip, the Beddagana Wetland Park prepared for its quieter hour — the hour when wetlands speak in their own language.

World Wetlands Day was marked a little early this year, but time felt irrelevant at Beddagana. Nature lovers, students, scientists and seekers gathered not for a ceremony, but for listening. Partnering with Park authorities, Dilmah Conservation opened the wetland as a living classroom, inviting more than a 100 participants to step gently into an ecosystem that survives — and protects — a capital city.

Wetlands, it became clear, are not places of stillness. They are places of conversation.

Beyond the surface

In daylight, Beddagana appears serene — open water stitched with reeds, dragonflies hovering above green mirrors.

Yet beneath the surface lies an intricate architecture of life. Wetlands are not defined by water alone, but by relationships: fungi breaking down matter, insects pollinating and feeding, amphibians calling across seasons, birds nesting and mammals moving quietly between shadows.

Participants learned this not through lectures alone, but through touch, sound and careful observation. Simple water testing kits revealed the chemistry of urban survival. Camera traps hinted at lives lived mostly unseen.

Demonstrations of mist netting and cage trapping unfolded with care, revealing how science approaches nature not as an intruder, but as a listener.

Again and again, the lesson returned: nothing here exists in isolation.

Learning to listen

Perhaps the most profound discovery of the day was sound.

Wetlands speak constantly, but human ears are rarely tuned to their frequency. Researchers guided participants through the wetland’s soundscape — teaching them to recognise the rhythms of frogs, the punctuation of insects, the layered calls of birds settling for night.

Then came the inaudible made audible. Bat detectors translated ultrasonic echolocation into sound, turning invisible flight into pulses and clicks. Faces lit up with surprise. The air, once assumed empty, was suddenly full.

It was a moment of humility — proof that much of nature’s story unfolds beyond human perception.

Sethil on camera trapping

The city’s quiet protectors

Environmental researcher Narmadha Dangampola offered an image that lingered long after her words ended. Wetlands, she said, are like kidneys.

“They filter, cleanse and regulate,” she explained. “They protect the body of the city.”

Her analogy felt especially fitting at Beddagana, where concrete edges meet wild water.

She shared a rare confirmation: the Collared Scops Owl, unseen here for eight years, has returned — a fragile signal that when habitats are protected, life remembers the way back.

Small lives, large meanings

Professor Shaminda Fernando turned attention to creatures rarely celebrated. Small mammals — shy, fast, easily overlooked — are among the wetland’s most honest messengers.

Using Sherman traps, he demonstrated how scientists read these animals for clues: changes in numbers, movements, health.

In fragmented urban landscapes, small mammals speak early, he said. They warn before silence arrives.

Their presence, he reminded participants, is not incidental. It is evidence of balance.

Narmadha on water testing pH level

Wings in the dark

As twilight thickened, Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda introduced mist netting — fine, almost invisible nets used in bat research.

He spoke firmly about ethics and care, reminding all present that knowledge must never come at the cost of harm.

Bats, he said, are guardians of the night: pollinators, seed dispersers, controllers of insects. Misunderstood, often feared, yet indispensable.

“Handle them wrongly,” he cautioned, “and we lose more than data. We lose trust — between science and life.”

The missing voice

One of the evening’s quiet revelations came from Sanoj Wijayasekara, who spoke not of what is known, but of what is absent.

In other parts of the region — in India and beyond — researchers have recorded female frogs calling during reproduction. In Sri Lanka, no such call has yet been documented.

The silence, he suggested, may not be biological. It may be human.

“Perhaps we have not listened long enough,” he reflected.

The wetland, suddenly, felt like an unfinished manuscript — its pages alive with sound, waiting for patience rather than haste.

The overlooked brilliance of moths

Night drew moths into the light, and with them, a lesson from Nuwan Chathuranga. Moths, he said, are underestimated archivists of environmental change. Their diversity reveals air quality, plant health, climate shifts.

As wings brushed the darkness, it became clear that beauty often arrives quietly, without invitation.

Sanoj on female frogs

Coexisting with the wild

Ashan Thudugala spoke of coexistence — a word often used, rarely practiced. Living alongside wildlife, he said, begins with understanding, not fear.

From there, Sethil Muhandiram widened the lens, speaking of Sri Lanka’s apex predator. Leopards, identified by their unique rosette patterns, are studied not to dominate, but to understand.

Science, he showed, is an act of respect.

Even in a wetland without leopards, the message held: knowledge is how coexistence survives.

When night takes over

Then came the walk: As the city dimmed, Beddagana brightened. Fireflies stitched light into darkness. Frogs called across water. Fish moved beneath reflections. Insects swarmed gently, insistently. Camera traps blinked. Acoustic monitors listened patiently.

Those walking felt it — the sense that the wetland was no longer being observed, but revealed.

For many, it was the first time nature did not feel distant.

Faunal diversity at the Beddagana Wetland Park

A global distinction, a local duty

Beddagana stands at the heart of a larger truth. Because of this wetland and the wider network around it, Colombo is the first capital city in the world recognised as a Ramsar Wetland City.

It is an honour that carries obligation. Urban wetlands are fragile. They disappear quietly. Their loss is often noticed only when floods arrive, water turns toxic, or silence settles where sound once lived.

Commitment in action

For Dilmah Conservation, this night was not symbolic.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Rishan Sampath said conservation must move beyond intention into experience.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “And they understand what they experience.”

The Beddagana initiative, he noted, is part of a larger effort to place science, education and community at the centre of conservation.

Listening forward

As participants left — students from Colombo, Moratuwa and Sabaragamuwa universities, school environmental groups, citizens newly attentive — the wetland remained.

It filtered water. It cooled air. It held life.

World Wetlands Day passed quietly. But at Beddagana, something remained louder than celebration — a reminder that in the heart of the city, nature is still speaking.

The question is no longer whether wetlands matter.

It is whether we are finally listening.

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAll set for Global Synergy Awards 2026 at Waters Edge