Features

Sumithra peries looking back in nostalgia

By Uditha Devapriya

Sri Lanka’s oldest living filmmaker, Sumitra Peries, stands shoulder to shoulder with South Asia’s pioneering woman artist-intellectuals, including her childhood heroine, Minnette de Silva. Yet, barring a comprehensive biography by Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin, no writer has attempted to locate her life and work in the pantheon of South Asian cinema. A version of this article appeared in Himal Mag Southasia late last month.

The cinema of South Asia blows up in a riot of colour and spectacle, offering a melange of romance, action, and history. Despite its modest scale, this is one of the biggest film industries in the world, worth around 180 billion rupees (roughly 2.4 billion dollars) in India alone. Today, it has transformed into a category of its own, mixing different genres and, at least in India, earning the apt moniker “masala cinema.”

However, while many scholars have written on this industry, few among them seem to have noted its contribution in a rather unlikely front: women’s filmmaking.

Surprising as it may seem, several women made their mark as directors in South Asia. While attempting a chronology is difficult, the first such director is considered to be Fatma Begum. In 1926, when Lillian Gish considered ending her career with D. W. Griffith, and MGM was offering her a six-movie deal, Begum made her first film through her own production house, Fatma Films. Later, in Pakistan, Parveen Rizvi and Shamim Ara made their debuts as directors, while much later, in Bangladesh, Kohinoor Akhter followed suit.

What bound these women together was the way their careers developed. All of them had to transition from acting to directing. It was later, with the onset of a New Wave, in Indian cinema, in the 1980s, that a new generation of filmmakers, among them Mira Nair and Deepa Mehta, took centre stage. The only notable exception to this trend, who continues to stand out, is to be found outside India.

Long orientalised for its sandy beaches and mist-clad mountains, Sri Lanka boasts of an obscure but vibrant cinema. Though dominated by men, women, too, have made their mark in it, and not just in acting. Among them, one name stands out: Sumitra Peries, the country’s oldest living filmmaker.

With 10 films to her name, Sumitra has emerged as one of the country’s foremost cultural icons. Her career offers a contrast to that of many of her contemporaries. For one thing, unlike most South Asian woman directors her age, such as Aparna Sen, she never took up acting: she began her career as an assistant director and an editor. Moreover, unlike them, she travelled extensively and studied cinema in Europe. It is this that makes her work, even her life, stand out.

With 10 films to her name, Sumitra has emerged as one of the country’s foremost cultural icons. Her career offers a contrast to that of many of her contemporaries. For one thing, unlike most South Asian woman directors her age, such as Aparna Sen, she never took up acting: she began her career as an assistant director and an editor. Moreover, unlike them, she travelled extensively and studied cinema in Europe. It is this that makes her work, even her life, stand out.

Sumitra Peries was born Sumitra Gunawardena on March 24, 1935, in the village of Payagala, 40 miles from the island’s capital, Colombo. Her mother hailed from a wealthy family of arrack distillers, her father from a household of fervent political radicals.

While Sumitra’s paternal grandfather had participated in the resistance against colonial authorities, two of her uncles became leading socialist politicians in British Ceylon. One of them, Philip, whose association with Marxism had taken him to far-flung places, such as the Pyrenees during the Spanish Civil War, went on to dominate the political stage in the country.

By contrast her father, a Proctor, had not been as politically inclined: barring one unsuccessful attempt to get into the country’s State Council in 1936, his career was largely overshadowed by his brothers. Nevertheless, Sumitra recalls, “our home in Boralugoda was open to radical politicians. They made it their lunch stop and rest-house.”

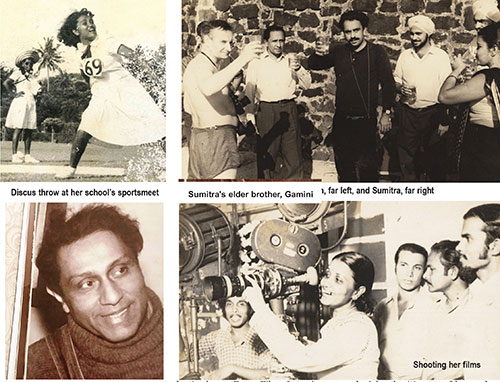

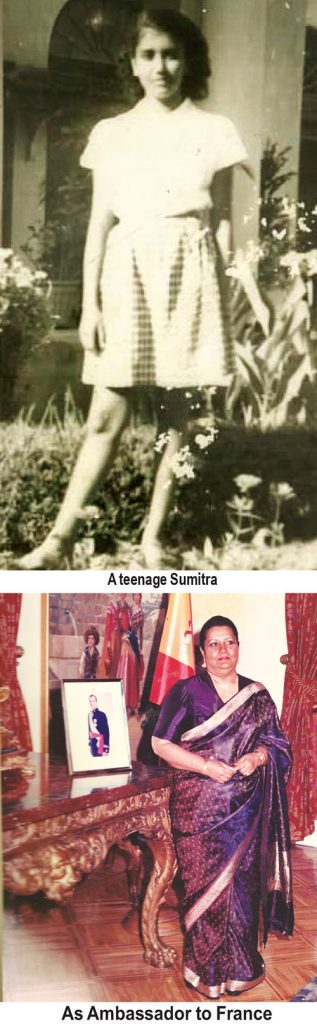

After she turned 13, in 1948, when Sri Lanka gained independence from the British, her family decided to move to Colombo. She transferred from a Catholic school, St Mary’s College, in her paternal village of Avissawella, to Visakha Vidyalaya, Sri Lanka’s leading Buddhist girls’ school. The first photograph of her in the press shows a girl throwing a discus at a sportsmeet at Visakha, exuding a youthful, defiant ardour.

Two years later, her mother passed away. Devastated by the loss, her elder brother, Gamini, left the country. Sumitra recalls how, a few years later, he asked her to join him in Europe. “I agreed at once. In 1956, I got aboard a P&O liner and set sail to the Mediterranean, all on my own.” She was not quite 21.

Arriving in Naples, Sumitra met Gamini and went to Malta. “He had a yacht docked there, and was leading a rather bohemian life with some friends.”

Over the next six months, Sumitra, Gamini, and their friends “sailed along the Italian and French coasts, savouring the Mediterranean.” At Saint-Tropez, she happened to see Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim making And God Created Woman. Her first sight of a movie set intrigued her greatly.

“I didn’t know what to do next. We decided on settling in Lausanne. My brother returned to Sri Lanka, leaving me behind in a world far from home.”

Lausanne failed to grow on her: “I longed to see France, on the other side.” A train and cab ride later, she was in Paris, “without a penny in my purse.”

On family instructions, she was soon boarded at the Ceylon Legation. There she met a man who was to change the course of the Sri Lankan cinema – with a significant, if underrated, contribution from her.

This was Lester James Peries, widely regarded as Sri Lanka’s pre-eminent filmmaker, and before long, her husband.

Lester proposed to Sumitra that she go to England. She agreed, enrolling at the London School of Film Technique. Founded in 1956, the LSFT was located in a suburb in Brixton. Less tempestuous than the Mediterranean, it offered Sumitra a more stable home.

Among her lecturers and peers at the School, she remembers Lindsay Anderson the most. Over time, the two of them got to know each other well. “He knew Lester long before he met me. The three of us became very good friends.”

Sumitra excelled in her studies, but finding a job in London was not easy for her. Only after knocking on the doors of Elizabeth Mai-Harris, one of Britain’s leading subtitling firms, was she offered work in the industry. “My fluency in French helped,” she remembers.

After a while, however, she longed to be back home. On Gamini’s advice, she returned to Sri Lanka, ending up as the only female crew member aboard Lester Peries’s second film, Sandesaya (The Message, 1960). Four years later they married, and remained together until Lester’s death in 2018.

In 1964, Sumitra began editing films. More than a decade later, in 1978, she ventured into directing with Gehenu Lamayi (Girls), following it up with eight more films, including her most recent, Vaishnavi (The Goddess), in 2018. She would go on to serve in other capacities as well, prominently as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary for France and Spain from 1995 to 1999.

The essential themes of Sumitra’s work are in Gehenu Lamayi: the innocence of childhood, the burdens of women in patriarchal society, the rift between rich and poor, the torments of adolescent love. Lacking the song-and-dance sequences of South Asian blockbusters, her films are sharp, often searing, in their critique of male chauvinism.

Most of her characters come from lower middle-class backgrounds, with a few, like Kusum from Gehenu Lamayi, hailing from the rural peasantry. Thwarted in their desires, they often resort to desperate measures: after discovering that her childhood lover has married someone else, for instance, Nirmala from Ganga Addara (By the Bank of the River, 1980) commits suicide. In Sagara Jalaya Madi Handuwa Oba Handa (Letter Written on the Sand, 1988), which many consider to be her finest work, the protagonist is a sensitive young boy whose mother toils hard for him after her husband, his father, falls off a tree and dies. The son writes an imaginary letter on the sand, imploring his uncle to take him away and employ him at his shop so that he can ease his mother’s burdens.

Most of her characters come from lower middle-class backgrounds, with a few, like Kusum from Gehenu Lamayi, hailing from the rural peasantry. Thwarted in their desires, they often resort to desperate measures: after discovering that her childhood lover has married someone else, for instance, Nirmala from Ganga Addara (By the Bank of the River, 1980) commits suicide. In Sagara Jalaya Madi Handuwa Oba Handa (Letter Written on the Sand, 1988), which many consider to be her finest work, the protagonist is a sensitive young boy whose mother toils hard for him after her husband, his father, falls off a tree and dies. The son writes an imaginary letter on the sand, imploring his uncle to take him away and employ him at his shop so that he can ease his mother’s burdens.

Sumitra’s aesthetic sensibility is distinct: according to British filmmaker Mark Cousins, “she uses zooms like Robert Altman, probing shyness and tentative love.” Sumitra herself seems to be aware of a certain quality of meticulousness in her work: “I often get an urge to recompose the mise-en-scène, even to prettify it. I think that shows in the final product.” For Cousins, that reveals “what a great visual thinker she is.”

By Sumitra’s own confession, her attitude to women was shaped by the women who figured in her life, including her mother. When asked about the films she likes, she at once mentions Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. “I remember seeing Renée Falconetti’s face and being enthralled by it. I could never forget that face. It came back to me, many times in fact, when I started directing films.”

Despite the high praise she has won, however, she has also received scathing criticism. Some critics have labelled her work as “feminine” and accused her of not being sufficiently “feminist”, because of the way in which her female characters succumb to their plight – such as when Kusum from Gehenu Lamayi bitterly accepts a life of loveless poverty as her “fate.” Thus, the authors of Profiling Sri Lankan Cinema conclude that she “has not gone far enough as a director with feminist intentions.”

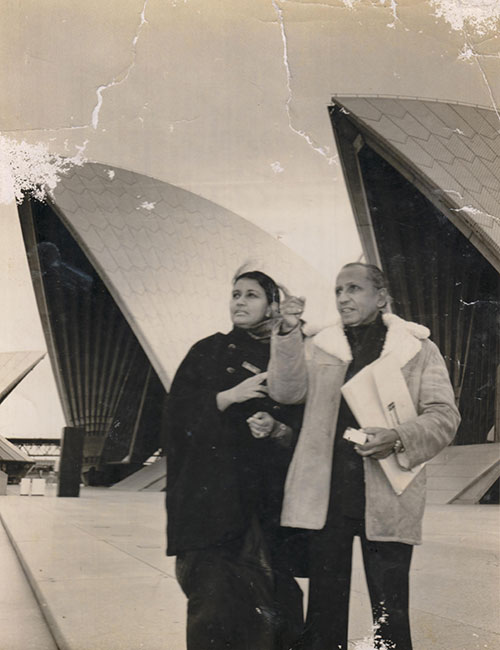

With Lester James Peries in Sydney

With Lester James Peries in Sydney

Sumitra’s response to these criticisms is that she can portray women “as someone other than who they are only by manipulating the story.” In the few instances when she in fact attempts this – as in Yahalu Yeheli (Boyfriends and Girlfriends, 1982), where the heroine disobeys her father, a landlord, and joins some villagers protesting his hold over them – one notices a tinge of artificiality. Overall, however, she sticks to a realist principle: “I prefer to depict women as they are, rather than who they should be.”

Today Sumitra resides in Mirihana, a quiet suburb located about six miles from the capital. She and her husband spent their married life in Colombo, in a house along a road that bears his name. Yet following his death, owing to certain unfortunate circumstances involving the legal title to their residence, she had to vacate her premises. She hasn’t come to regret the shift: “It’s much quieter here, in tune with my sensibility.”

Still active and working on her next project, at 87 Sumitra remains open to the possibilities of her medium. It goes without saying that her work stands out in the world of South Asian cinema. While being utterly modest about her achievements, she admitted one thing the last time I met her: “I rebelled against the idea of what a woman had to be in my society, as a girl and a director. In the end, despite those strictures, I prevailed.”

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

More state support needed for marginalised communities

Message from Malaiyaha Tamil community to govt:

Insights from SSA Cyclone Ditwah Survey

When climate disasters strike, they don’t affect everyone equally. Marginalised communities typically face worse outcomes, and Cyclone Ditwah is no exception. Especially in a context where normalcy is far from “normal”, the idea of returning to normalcy or restoring a life of normalcy makes very little sense.

The island-wide survey (https://ssalanka.org/reports/) conducted by the Social Scientists’ Association (SSA), between early to mid-January on Cyclone Ditwah shows stark regional disparities in how satisfied or dissatisfied people were with the government’s response. While national satisfaction levels were relatively high in most provinces, the Central Province tells a different story.

Only 35.2% of Central Province residents reported that they were satisfied with early warning and evacuation measures, compared to 52.2% nationally. The gap continues across every measure: just 52.9% were satisfied with immediate rescue and emergency response, compared with the national figure of 74.6%. Satisfaction with relief distribution in the Central Province is 51.9% while the national figure stands at 73.1%. The figures for restoration of water, electricity, and roads are at a low 45.9% in the central province compared to the 70.9% in national figures. Similarly, the satisfaction level for recovery and rebuilding support is 48.7% in the Central Province, while the national figure is 67.0%.

A deeper analysis of the SSA data on public perceptions reveals something important: these lower satisfaction rates came primarily from the Malaiyaha Tamil population. Their experience differed not just from other provinces, but also from other ethnic groups living in the Central Province itself.

The Malaiyaha Tamil community’s vulnerability didn’t start with the cyclone. Their vulnerability is a historically and structurally pre-determined process of exclusion and marginalisation. Brought to Sri Lanka during British rule to work for the empire’s plantation economies, they have faced long-term economic exploitation and have repeatedly been denied access to state support and social welfare systems. Most estate residents still live in ‘line rooms’ and have no rights to the land they cultivate and live on. The community continues to be governed by an outdated estate management system that acts as a barrier to accessing public and municipal services such as road repair, water, electricity and other basic infrastructures available to other citizens.

As far as access to improved water sources is concerned, the Sri Lanka Demographic Health Survey (2016) shows that 57% of estate sector households don’t have access to improved water sources, while more than 90% of households in urban and rural areas do. With regard to the level of poverty, as the Department of Census and Statistics (2019) data reveals, the estate sector where most Malaiyaha Tamils live had a poverty headcount index of 33.8%; more than double the national rate of 14.3%. These statistics highlight key indicators of the systemic discrimination faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community.

Some crucial observations from the SSA data collectors who enumerated responses from estate residents in the survey reveal the specific challenges faced by the Malaiyaha Tamils, particularly in their efforts to seek state support for compensation and reconstruction.

First, the Central Province experienced not just flooding but also the highest number of landslides in the island. As a result, some residents in the region lost entire homes, access roadways, and other basic infrastructures. The loss of lives, livelihoods and land was at a higher intensity compared to the provinces not located in the hills. Most importantly, the Malaiyaha Tamil community’s pre-existing grievances made them even more vulnerable and the government’s job of reparation and restitution more complex.

Early warnings hadn’t reached many areas. Some data collectors said they themselves never heard any warnings in estate areas, while others mentioned that early warnings were issued but didn’t reach some segments of the community. According to the resident data collectors, the police announcements reached only as far as the sections where they were able to drive their vehicles to, and there were many estate roads that were not motorable. When warnings did filter through to remote locations, they often came by word of mouth and information was distorted along the way. Once the disaster hit, things got worse: roads were blocked, electricity went out, mobile networks failed and people were cut off completely.

Emergency response was slow. Blocked roads meant people could not get to hospitals when they needed urgent care, including pregnant mothers. The difficult terrain and poor road conditions meant rescue teams took much longer to reach affected areas than in other regions.

Relief supplies didn’t reach everyone. The Grama Niladhari divisions in these areas are huge and hard to navigate, making it difficult for Grama Niladharis to reach all places as urgently as needed. Relief workers distributed supplies where vehicles could go, which meant accessible areas got help while remote communities were left out.

Some people didn’t even try to go to safety centres or evacuation shelters set up in local schools because the facilities there were already so poor. The perceptions of people who did go to safety centres, as shown in the provincial data, reveal that satisfaction was low compared to other affected regions of the country. Less than half were satisfied with space and facilities (42.1%) or security and protection (45.0%). Satisfaction was even lower for assistance with lost or damaged documentation (17.9%) and information and support for compensation applications (28.2%). Only 22.5% were satisfied with medical care and health services below most other affected regions.

Restoring services proved nearly impossible in some areas. Road access was the biggest problem. The condition of the roads was already poor even before the cyclone, and some still haven’t been cleared. Recovery is especially difficult because there’s no decent baseline infrastructure to restore, hence you can’t bring roads and other public facilities back to a “good” condition when they were never good, even before the disaster.

Water systems faced their own complications. Many households get water from natural sources or small community projects, and not the centralised state system. These sources are often in the middle of the disaster zone and therefore got contaminated during the floods and landslides.

Long-term recovery remains stalled. Without basic infrastructure, areas that are still hard to reach keep struggling to get the support they need for rebuilding.

Taken together, what do these testaments mean? Disaster response can’t be the same for everyone. The Malaiyaha Tamil community has been double marginalised because they were already living with structural inequalities such as poor infrastructure, geographic isolation, and inadequate services which have been exacerbated by Cyclone Ditwah. An effective and fair disaster response needs to account for these underlying vulnerabilities. It requires interventions tailored to the historical, economic, and infrastructural realities that marginalized communities face every day. On top of that, it highlights the importance of dealing with climate disasters, given the fact that vulnerable communities could face more devastating impacts compared to others.

(Shashik Silva is a researcher with the Social Scientists’ Association of Sri Lanka)

by Shashik Silva ✍️

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoA question of national pride

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency