Features

Sri Lanka’s great IMF lie

Decades of looking to the IMF for salvation has yielded only crises. Sri Lanka’s economic crisis demands urgent relief measures for a desperate citizenry and a new, self-sufficient model of development

by Ahilan Kadirgamar and Devaka Gunawardena

Sri Lanka has been subject to a great lie: the IMF solution! For close to a year now, the country has been implementing the International Monetary Fund’s recommendations with complete obedience. The sudden devaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee, a drastic increase in interest rates, the withdrawal of fuel subsidies and severe cuts to state expenditure all amount to harsh austerity measures. The consequence is economic devastation as the country sinks into a depression. Millions now suffer dwindling incomes, tremendous increases in the cost of living, food insecurity and even starvation.

Yet the much-touted IMF funds presented as a way to salvation, a meagre USD 2.9 billion over four years under the proposed agreement, have proved elusive. Compare this amount to Sri Lanka’s foreign earnings for last year, which added up to USD 18 billion. The IMF insists that Sri Lanka first convince a range of creditors to commit to restructuring its defaulted external debt before the organisation’s Executive Board will release the funds. But Sri Lanka’s economy is in free fall. Its GDP contracted by roughly a tenth last year and is on the path to continued contraction this year. Under these circumstances, the IMF agreement and its paltry funds may as well go into the dustbin.

Some of us have seen this crisis coming for a long time. A few months after the end of the civil war in May 2009, Sri Lanka obtained an IMF Stand-By Arrangement of USD 2.6 billion. This gave the green light to a considerable inflow of speculative foreign capital, in addition to commercial borrowings at extremely high interest rates in the form of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs). At that point, the warning bells began ringing for critical analysts who could see the consequences. But back-slapping and self-congratulation among Sri Lanka’s elites continued amid a boom in economic growth built on a dubious basis, including speculative investment in urban beautification and needlessly large infrastructure projects. This debt-driven boom soon petered out.

Sri Lanka then faced balance-of-payments problems, which pushed it towards an IMF Extended Fund Facility of USD 1.5 billion in June 2016. Some of us sounded the alarm again as the government at the time, led by Ranil Wickremesinghe, pursued another IMF-led solution. But, again, our critique fell on deaf ears. Worryingly, the following month, with the IMF’s approval, Sri Lanka went ahead and floated another USD 1.5 billion in ISBs. Indeed, the latest IMF agreement – the 16th deal between Sri Lanka and the organisation over the decades – offered nothing new. Rather, it promoted Sri Lanka’s continued liberalisation of trade and capital accounts, dating back to the opening of the economy in 1978. The crisis tendencies in the Sri Lankan economy were ramified through adherence to IMF packages.

Historical memory is short in Sri Lanka, particularly among the elite. The crisis accelerated with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic three years ago. Again, we warned of the imminent dangers of an unsustainable balance of payments and the need to drastically reassess and reprioritise imports for the purpose of maintaining foreign reserves, given decreasing streams of foreign earnings. That would have meant restricting the import of luxury consumer goods while using the available foreign exchange for essential supplies and intermediate goods necessary to boost domestic production. The arrogant Rajapaksa regime then in power nevertheless persisted in the blind hope that fortunate times were just around the corner. It argued that tourism, for example, would soon pick up. Meanwhile, the opposition and neoliberal think-tanks proposed yet another IMF agreement as the magic bullet. Worse, they even started calling for an early default on Sri Lanka’s external debt. Their convoluted logic was that once the country defaulted, it would have to surrender to the IMF and all its conditionalities, such as austerity and fiscal consolidation. There could be no way forward other than with the IMF.

That is exactly what the government led by Gotabaya Rajapaksa did in April 2022. It prematurely defaulted on its external debt while the finance minister went on pilgrimage to Washington DC to the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank. The default was premature because only USD 78 million in debt-servicing was due that month, while the next large ISB repayment, of USD 1 billion, was due in July 2022. Only in Sri Lanka could the elite celebrate when the country defaulted on its sovereign debt for the first time in its history. They were confident that Sri Lanka would get bridge financing from donors, an IMF agreement with additional funds in three months, and a rapid process of debt restructuring. Ten months later, the outcome of these expectations remains a shameful zero. There is no more bridge financing. No IMF funds. And an agreement on debt restructuring appears uncertain at best.

Given all the above, Sri Lanka is a case in point of consistently insipid economic policymaking. It is also a study in how the myth of an IMF quick-fix can paralyse a country, putting on hold policies and relief measures urgently needed to help a citizenry drowning in economic depression. As the country awakes to the great lie of an IMF solution, it is forced to go back to the drawing board – not just to deal with the social devastation and political backlash that the IMF agreement is bound to generate, but also because the global order that provided its reference points is unravelling.

From debt to a new development model

Sri Lanka’s long engagement with the IMF and the broader neoliberal policy consensus – austerity, privatisation, and the liberalisation of trade and capital markets – has been an utter and complete failure. Nevertheless, for the IMF and Sri Lanka’s establishment, resolution of the crisis appears to call for the introduction of austerity measures like the ones applied to many other countries that have experienced sovereign default, along with restructuring of defaulted debt. The idea is that Sri Lanka’s problems are rooted in a fundamental mismatch between its macroeconomic indicators and the debt it has accumulated.

This framework is being applied, however, in the context of a world order that is fast breaking down because of the contradictions of neoliberal globalisation. Over the last decades, the push for free trade, unfettered global financial flows and the privatisation of essential services has continued to expose countries to the crisis-ridden dynamics of global capitalism. But everything appears to be coming to a head, epitomised in many ways by the case of Sri Lanka. As major publications such as the Financial Times have noted, although exogenous shocks such as the Covid-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine have played a role, these have interacted with underlying trends in the global economy. This includes extreme wealth inequality and an unsustainable model of growth driven by financialisation, exposed most vividly by the global financial crisis of 2008.

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, however, and coincident with the end of the civil war, Sri Lanka was one of a series of emerging market “success stories” celebrated by boosters of neoliberalism. Now that the country’s shaky financial structure has been exposed, establishment commentators around the world are instead using Sri Lanka as an example of crony capitalism and corruption. Supposedly, such bad actors can only be routed by further imposing the rationality of the market on public institutions. Whereas the big banks in the United States responsible for the 2008 crisis obtained bailouts from the state because they were “too big to fail,” Sri Lanka is apparently small enough that the rules of moral hazard once again apply. The failed logic of the neoliberal development model – including the reliance on external-oriented policies, from tourism to foreign commercial borrowings – here justifies further entrenching it through austerity. Because of the country’s severe economic crisis, however, such a remedy means that people suffer and possibly even perish from what the sociologist Karl Polanyi called “social exposure.” Child malnutrition is skyrocketing and food insecurity is becoming pervasive – recent estimates from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation indicate that roughly a fourth of Sri Lanka’s population is food insecure. Even this extreme suffering is unlikely to dislodge the elite consensus about an IMF solution. But the disruptive political and social consequences, and resulting waves of agitation, will continue.

Moreover, Sri Lanka’s crisis is occurring at the conjuncture of major global developments. Global growth, especially in trade, is likely to continue slowing in the face of a complex set of challenges, from geopolitical polarisation to the impact of climate change. In this scenario, how can Sri Lanka’s debt be made sustainable by further exposing the country to these chilling headwinds? The central plank of the IMF solution – that Sri Lanka achieve a primary surplus by 2025 – stands in direct contradiction to the lack of the public investment needed to cope with these shocks. Conventional debt-sustainability analysis is predicated on the belief that by engaging in macroeconomic reforms such as fiscal consolidation, defaulting countries can regain their financial footing by having the surplus funds to both repay old loans and service new ones. However, in the case of Sri Lanka, which is already undergoing an economic depression, national private investment is withdrawing, and speculative capital is fleeing the country. The idea that foreign investors will step in to fill the breach flies in the face of Sri Lanka’s long experience with similar false projections.

Sri Lanka did not always have an unshakeable belief in the benefits of subordination to global capital. After the 1956 general election, there was a clear push to challenge the colonial relations in which the country’s comprador elites were embedded. Through a new balance of class forces, there was much greater emphasis on industrialisation focussed on import substitution, to try and diversify the economy away from plantation exports. Sri Lanka undertook major investments in critical industries, such as those producing intermediate and capital goods, including with support from socialist countries. But even these efforts were constrained by over-reliance on a narrow political base among the urban working class and a lack of rural mobilisation. By the time of the global economic downturn of the 1970s, the radical wing of the left-leaning United Front was led by NM Perera, the finance minister. It made a belated attempt to prioritise self-sufficiency in food production and address the immediate concerns of working-class people, especially given rising global prices for essential goods. But these efforts failed due to internal contradictions within the ruling coalition led by the bourgeois Sri Lanka Freedom Party, the consolidation of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism and state repression, external pressure from the West and the rising frustration of the electorate.

The subsequent regime, led by JR Jayewardene, introduced the open-economy reforms in 1978, which meant a strong emphasis on liberalisation. Sri Lanka’s engagement with the outside world reverted to subordination to powerful institutions that represented the interests of global capital. The IMF and the World Bank provided the necessary justification in terms of access to external finance. Meanwhile, the Jayewardene regime suppressed organised labour, including by crushing the general strike of 1980. In this and other ways, the regime prepared a more conducive terrain for extraction and exploitation. The beginning of the civil war between the government and Tamil separatists in the country’s north and east in 1983 put some constraints on this approach, as the state continued to rely on mobilisation in the south. But the overall trajectory was epitomised by the collapse of any real alternative to neoliberal policies. The consensus was that for Sri Lanka to develop it would have to import its economic vision from outside – a vision clearly shaped by the interests of global capital. The processes of financialisation and debt-driven growth accelerated with the end of the civil war.

This strategy has failed to bear fruit in terms of real improvements in working people’s livelihoods. It has also triggered the current crisis. Nevertheless, in the many years since Sri Lanka embarked on liberalisation, justification for foreign commercial borrowing has been rooted in the enduring assumption that the country need only “unlock its growth potential”. A range of services and industries meant to earn foreign exchange have been bandied as model opportunities. After the early days of the open economy, it became clear that a developed garment industry was not a precursor to moving up the “global value chain.” This was especially true in the absence of a clear, concerted intervention by the state in the form of industrial policy. Global institutions and policy-makers then pivoted to celebrating the rise of the service economy, including the boom in tourism. Sri Lanka continued to depend, however, on a hidden economy of remittances from migrant workers abroad, which is also now under strain.

The idea that Sri Lanka can achieve higher stages of development by pursuing the same growth path rooted in dependency on the external sector is a non-starter. The neoliberal development model has collapsed. The Sri Lankan establishment has practically admitted as much by seeking lower-income status for the country to obtain more concessional financing from international donors and aid agencies. At the same time, the government, led by Ranil Wickremesinghe, is eager to celebrate the return of tourists after a long absence caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the Easter Sunday terror attacks in 2019. But the reality is that tourism will not be enough to revive Sri Lanka’s growth during a period of painful austerity. The same goes for any number of hare-brained ideas that may now be touted by the country’s economic establishment in the absence of serious thinking about an alternative development model.

Sri Lanka’s lop-sided economic structure, with a bloated import bill and unrestrained financial speculation, now faces a reckoning. The years of conspicuous consumption through imports from abroad are over. The question is, how can investment be channelled into those sectors necessary for the country to achieve self-sufficiency in the goods and services ordinary people need for survival? This perspective is a far cry from the IMF solution, which presupposes Sri Lanka’s continued subordination to a global economic structure that has clearly failed. Taking up the question of an alternative means returning to issues that had supposedly been bypassed with the triumph of neoliberal globalisation. It requires revisiting the many “reforms” – from the push for trade and capital-account liberalisation to the promotion of foreign direct investment and privatisation – that it has entailed.

Towards self-sufficiency

Under these circumstances, the idea of self-sufficiency offers a crucial response to the rapidly changing, uncertain global order. This churn may provide an opportunity for foresighted actors within Sri Lanka to demand a fundamental re-conceptualisation of how external engagement fits into the country’s development model. If it is imperative to revive the country’s domestic food production, for example, how would this flow into a broader rethinking of the composition of intermediate imports needed for production? What type of external financing would be necessary to develop the domestic food system?

Sri Lanka’s domestic debt is also a critical part of the equation for overcoming the current economic depression. That includes the need for counter-cyclical spending, as opposed to pro-cyclical policies of fiscal consolidation. But external development finance would also continue to play a role. The key question is whether such borrowings are integrated into a process of planning, so that an alternative development vision takes precedence over the mainstream understanding of market-steered investment that has long shaped countries such as Sri Lanka. The country must push back against global capital geared towards the sole end of financial extraction. Indeed, the lion’s share of foreign direct investment into Sri Lanka went into speculative investment in real estate rather than ventures that increased local industrial production. Development financing should be reconfigured as part of a bottom-to-top restructuring of the economy, along with changes in trade policy away from excessive imports. That is necessary both to repay the current debt – with deep haircuts for creditors, if not debt cancellations – and as a means to develop Sri Lanka in the long run.

This alternative goes back to similar points made by development economists such as Ha-Joon Chang and Abhijit Sen, who were early critics of the Washington Consensus. Such critical economists recognised the flaws in the previous model of import substitution, but they framed it as an ongoing concern of the balance of social and class forces required to ensure that capital, as it grows, is also disciplined to invest in critical sectors. In Sri Lanka’s case, that process of disciplining capital must now include prioritising imports of essential and intermediate goods necessary for production. It also requires revamping the defunct public-distribution system to ensure food security and prevent outright starvation. As the economy stabilises, further measures must also include redistribution and investment through a wealth tax on existing property and assets.

Sri Lanka has to have stronger debates about its development vision, including a rethink on relations between its rural and urban arenas. There must be greater room for rural industries rooted in the livelihoods and reproductive needs of ordinary people. This is a far cry from the elites’ vision of the economy, which has repeatedly driven Sri Lanka into financial difficulties. There is now tremendous anger in the country because of the devastating fall in living standards. This discontent, in addition to the unravelling global order, may finally trigger a break with liberalisation.

For the IMF, of course, a programme rooted in self-sufficiency with wealth taxes and reinvigorated public investment will be a step too far. It is entrenched in its own institutional processes, despite the organisation’s fuzzy rhetoric around its newfound supposed awareness of the social implications of austerity-driven bailout agreements. Nevertheless, Sri Lanka’s crisis may offer a turning point for those global and domestic coalitions that are aiming to push back against renewed subordination to global financial capital. That means rethinking a number of trends that have long coalesced under the banner of economic liberalisation. After decades of repeated mistakes and failures, with consequences for the people on an unprecedented scale, will the establishment at last be forced to reconsider Sri Lanka’s development model? Himal Southasian

Features

US foreign policy-making enters critical phase as fascist threat heightens globally

It could be quite premature to claim that the US has closed ranks completely with the world’s foremost fascist states: Russia, China and North Korea. But there is no denying that the US is breaking with tradition and perceiving commonality of policy orientation with the mentioned authoritarian states of the East rather than with Europe and its major democracies at present.

It could be quite premature to claim that the US has closed ranks completely with the world’s foremost fascist states: Russia, China and North Korea. But there is no denying that the US is breaking with tradition and perceiving commonality of policy orientation with the mentioned authoritarian states of the East rather than with Europe and its major democracies at present.

Increasingly, it is seemingly becoming evident that the common characterization of the US as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’, could be a gross misnomer. Moreover, the simple fact that the US is refraining from naming Russia as the aggressor in the Russia-Ukraine conflict and its refusal to perceive Ukraine’s sovereignty as having been violated by Russia, proves that US foreign policy is undergoing a substantive overhaul, as it were. In fact, one could not be faulted, given this backdrop, for seeing the US under President Donald Trump as compromising its democratic credentials very substantially.

Yet, it could be far too early to state that in the traditional East-West polarity in world politics, that the US is now squarely and conclusively with the Eastern camp that comprises in the main, China and Russia. At present, the US is adopting an arguably more nuanced approach to foreign policy formulation and the most recent UN Security Council resolution on Ukraine bears this out to a degree. For instance, the UN resolution in question reportedly ‘calls for a rapid end to the war without naming Russia as the aggressor.’

That is, the onus is being placed on only Ukraine to facilitate an end to the war, whereas Russia too has an obligation to do likewise. But it is plain that the US is reflecting an eagerness in such pronouncements to see an end to the Ukraine conflict. It is clearly not for a prolongation of the wasting war. It could be argued that a negotiated settlement is being given a try, despite current international polarizations.

However, the US could act constructively in the crisis by urging Russia as well to ensure an end to the conflict, now that there is some seemingly friendly rapport between Trump and Putin.

However, more fundamentally, if the US does not see Ukraine’s sovereignty as having been violated by Russia as a result of the latter’s invasion, we are having a situation wherein the fundamental tenets of International Law are going unrecognized by the US. That is, international disorder and lawlessness are being winked at by the US.

It follows that, right now, the US is in cahoots with those powers that are acting autocratically and arbitrarily in international politics rather than with the most democratically vibrant states of the West, although a facile lumping together of the US, Russia and China, is yet not possible.

It is primarily up to the US voting public to take clear cognizance of these developments, draw the necessary inferences and to act on them. Right now, nothing substantive could be done by the US voter to put things right, so to speak, since mid-term US elections are due only next year. But there is ample time for the voting public to put the correct perspective on these fast-breaking developments, internationally and domestically, and to put their vote to good use in upcoming polls and such like democratic exercises. They would be acting in the interest of democracy worldwide by doing so.

More specifically it is up to Donald Trump’s Republican voter base to see the damage that is being done by the present administration to the US’ standing as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’. They need to bring pressure on Trump and his ‘inner cabinet’ to change course and restore the reputation of their country as the foremost democracy. In the absence of such action it is the US citizenry that would face the consequences of Trump’s policy indiscretions.

Meanwhile, the political Opposition in the US too needs to get its act together, so to speak, and pressure the Trump administration into doing what is needed to get the US back to the relevant policy track. Needless to say, the Democratic Party would need to lead from the front in these efforts.

While, in the foreign policy field the US under President Trump could be said to be acting with a degree of ambivalence and ambiguity currently, in the area of domestic policy it is making it all to plain that it intends to traverse a fascistic course. As has been proved over the past two months, white supremacy is being made the cardinal principle of domestic governance.

Trump has made it clear, for example, that his administration would be close to ethnic chauvinists, such as the controversial Ku Klux Klan, and religious extremists. By unceremoniously rolling back the ‘diversity programs’ that have hitherto helped define the political culture of the US, the Trump administration is making no bones of the fact that ethnic reconciliation would not be among the government’s priorities. The steady undermining of USAID and its main programs worldwide is sufficient proof of this. Thus the basis has been adequately established for the flourishing of fascism and authoritarianism.

Yet, the US currently reflects a complex awareness of foreign policy questions despite having the international community wondering whether it is sealing a permanent alliance with the main powers of the East. For instance, President Trump is currently in conversation on matters in the external relations sphere that are proving vital with the West’s principal leaders. For example, he has spoken to President Emmanuel Macron of France and is due to meet Prime Minister Keir Starmer of the UK.

Obviously, the US is aware that it cannot ‘go it alone’ in resolving currently outstanding issues in external relations, such as the Ukraine question. There is a clear recognition that the latter and many more issues require a collaborative approach.

Besides, the Trump administration realizes that it cannot pose as a ‘first among equals’, given the complexities at ground level. It sees that given the collective strength of the rest of the West that a joint approach to problem solving cannot be avoided. This is particularly so in the case of Ukraine.

The most major powers of the West are no ‘pushovers’ and Germany, under a possibly Christian Democratic Union-led alliance in the future, has indicated as much. It has already implied that it would not be playing second fiddle to the US. Accordingly, the US is likely to steer clear of simplistic thinking in the formulation of foreign policy, going forward.

Features

Clean Sri Lanka – hiccups and remedies

by Upali Gamakumara,

Upali.gamakumara@gmail.com

The Clean Sri Lanka (CSL) is a project for the true renaissance the NPP government launched, the success of which would gain world recognition. It is about more than just cleaning up places. Its broader objectives are to make places attractive and happy for people who visit or use services in the country, focusing more on the services in public institutions and organisations like the SLTB. Unfortunately, these broader objectives are not apparent in its theme, “Clean Sri Lanka,” and therefore there is a misconception that keeping the environment clean is the main focus.

People who realise the said broader objectives are excited about a cleaner Sri Lanka, hoping the President and the government will tackle this, the way they are planning to solve other big problems like the economy and poverty. However, they do not see themselves as part of the solution.

From the management perspective, the CSL has a strategic plan that is not declared in that manner. When looking at the government policies, one can perceive its presence, the vision being “A Prosperous Nation and a Beautiful Life,” the mission “Clean Sri Lanka” and the broader objectives “a disciplined society, effective services, and a cleaner environment.” If the government published these as the strategy, there would have been a better understanding.

Retaining the spirit and expectations and continuing the ‘Clean Sri Lanka’ project is equally important as much as understanding its deep idea. For this, it needs to motivate people, which differs from those motivators that people push to achieve selfish targets. The motivation we need here is to evolve something involuntarily, known as Drivers. Drivers push for the survival of the evolution or development of any entity. We see the absence of apparent Drivers in the CSL project as a weakness that leads to sporadic hiccups and free flow.

Drivers of Evolution

Drivers vary according to the nature of envisaged evolution for progress. However, we suggest that ‘the force that pushes anything to evolve’ would fit all evolutions. Some examples are: ‘Fitting to survival’ was the driver of the evolution of life. Magnetism is a driver for the unprecedented development of physics – young Einstein was driven to enquire about the ‘attraction’ of magnets, eventually making him the greatest scientist of the 20th century.

Leadership is a Driver. It is essential but do not push an evolution continually as they are not sprung within a system involuntarily. This is one of the reasons why CSL has lost the vigour it had at its inception.

CSL is a teamwork. It needs ‘Drives’ for cohesion and to push forward continually, like the Quality Improvement Project of the National Health Service (NHS) in England. Their drivers are outlined differently keeping Aims as their top driver and saying: Aims should be specific and measurable, not merely to “improve” or “reduce,” engage stakeholders to define the aim of the improvement project and a clear aim to identify outcome measures.

So, we think that CSL needs Aims as defined by NHS, built by stakeholder participation to help refine the project for continuous evolution. This approach is similar to Deming’s Cycle for continual improvement. Further, two more important drivers are needed for the CSL project. That is Attitudinal Change and Punishment. We shall discuss these in detail under Psychoactive Environment (pSE) below.

Aside from the above, Competition is another driver in the business world. This helps achieve CSL objectives in the private sector. We can see how this Driver pushes, with the spread of the Supermarket chains, the evolution of small and medium retail shops to supermarket level, and in the private banks and hospitals, achieving broader objectives of CSL; a cleaner environment, disciplined behaviuor, efficient service, and the instillation of ethics.

The readers can now understand the importance of Drivers pushing any project.

Three Types of Entities and Their Drives

We understand, that to do the transformation that CSL expects, we need to identify or adopt the drivers separately to suit the three types of entities we have in the country.

Type I entities are the independent entities that struggle for their existence and force them to adopt drivers involuntarily. They are private sector entities, and their drivers are the commitment of leadership and competition. These drivers spring up involuntarily within the entity.

Type II are the dependent entities. To spring up drivers of these entities commitment of an appointed trustee is a must. Mostly in state-owned entities, categorized as Boards, Authorities, Cooperations, and the like. Their drivers do not spring up within or involuntarily unless the leader initiates. The Government of a country also falls into this type and the emergence of drivers depends on the leader.

Type III entities have neither independent nor dependent immediate leader or trustee. They are mostly the so-called ‘Public’ places like public-toilets, public-playgrounds, and public-beaches. No team can be formed as these places are open to any, like no-man-land. Achieving CSL objectives at these entities depends on the discipline of the public or the users.

Clean Sri Lanka suffers the absence of drivers in the second and third types of entities, as the appointed persons are not trustees but temporary custodians.

The writer proposes a remedy to the last two types of entities based on the theory of pSE explained below.

Psychoactive Environment (pSE) –

The Power of Customer Attraction

Research by the writer introduced the Psychoactive Environment (pSE) concept to explain why some businesses attract more customers than others who provide the same service. Presented at the 5th Global Conference on Business and Economics at Cambridge University in 2006, the study revealed that a “vibe” influences customer attraction. This vibe, termed pSE, depends on Three Distinct Elements, which can either attract or repel customers. A positive pSE makes a business more attractive and welcoming. This concept can help develop Drivers for Type II and III entities.

pSE is not an all-inclusive solution for CSL, but it lays the foundation for building Drivers and motivating entities to keep entrants attractive and contented.

The structure of the pSE

The three distinct Elements are the Occupants, Systems, and Environment responsible for making a pSE attractive to any entity, be it a person, institution, organization, or county. Each of these elements bears three qualities named Captivators. These captivators are, in simple terms, Intelligent, Nice, and Active in their adjective forms.

pSE theorizes that if any element fails to captivate the entrant’s mood by not being Intelligent, Nice, or Active, the pSE becomes negative, repelling the entrant (customer). Conversely, the positive pSE attracts the entrants if the elements are Intelligent, Nice, and Active.

For example, think person who comes to a Government Office for some service. He sees that the employees, service, and environment are intelligent, nice, and active, and he will be delighted and contented. He will not get frustrated or have any deterioration in national productivity.

The Significance of pSE in CSL

The Elements and the Captivators are universal for any entity. Any entity can easily find its path to Evolution or Progress determined by these elements and captivators. The intangible broader objectives can be downsised to manageable targets by pSE. Achievements of these targets make the entrants happy and enhance productivity – the expectation of Clean Sri Lanka (CSL).

From the perspective of pSE, now we can redefine the Clean Sri Lanka project thus:

To make the Elements of every entity in Sri Lanka: intelligent, Nice, and Active.

How Would the pSE be A Remedy for The Sporadic Hiccups?

We have seen two possible reasons for sporadic setbacks and the discontinuity of some projects launched by the CSL. They are:

The absence of involuntary Drivers for evolvement or progress

Poor attitudes and behaviors of people and leaders

Remedy for the Absence of Drivers

Setting up a system to measure customer or beneficiary satisfaction, and setting aims can build Drivers. The East London NHS principles help build the Aims that drive type II & II entities. The system must be designed to ensure continual improvement following the Deming Cycle. This strategy will create Drivers for Type I & II entities.

This process is too long to explain here therefore we refrain from detailing.

Attitudinal Change

The most difficult task is the attitudinal and behavioural change. Yet it cannot be postponed.

Punishment as a strategy

In developed countries, we see that people are much more disciplined than in the developing countries. We in developing countries, give credit to their superior culture, mitigating ours as rudimental. The long experience and looking at this affair from a vantage point, one will understand it is not the absolute truth. Their ruthless wars in the past, rules, and severe punishment are the reasons behind this discipline. For example, anyone who fails to wear a car seatbelt properly will be fined 400 AUD, nearly 80,000 LKR!

The lesson we can learn is, that in Sri Lanka, we need strong laws and strict punishment together with a type of strategic education as follows.

Psychological Approach as a Strategy

The psychological theory of attitude formation can be used successfully if some good programmes can be designed.

All attitude formations start with life experience. Formed wrong or negative attitudes can be reversed or instilled with correct attitudes by exposure to designed life experiences. The programmes have been developed using the concepts of Hoshin Kanri, Brainstorming, Cause-and-Effect analysis, and Teamwork, in addition to London NTS Quality Improvement strategies.

The experience and good responses we received for our pSE programs conducted at several institutions prove and have built confidence in our approach. However, it was a time, when governments or organisations did not pay much attention to cultural change as CSL expects in the country.

Therefore, we believe this is a golden opportunity to take the CSL supported by the pSE concept.

Features

Visually impaired but ready to do it their way

Although they are visually impaired youngsters, under the guidance of renowned musician Melantha Perera, these talented individuals do shine bright … hence the name Bright Light.

Although they are visually impaired youngsters, under the guidance of renowned musician Melantha Perera, these talented individuals do shine bright … hence the name Bright Light.

Says Melantha: “My primary mission is to nurture their talent and ensure their sustainable growth in music, and I’m thrilled to announce that Bright Light’s first public performance is scheduled for 7th June, 2025. The venue will be the MJF Centre Auditorium in Katubadda, Moratuwa.”

Melantha went on to say that two years of teaching, online, visually impaired youngsters, from various parts of the island, wasn’t an easy ride.

There were many ups and downs but Melantha’s determination has paid off with the forming of Bright Light, and now they are gearing up to go on stage.

According to Melantha, they have come a long way in music.

“For the past few months, we have been meeting, physically, where I guide them to play as a band and now they show a very keen interest as they are getting to the depth of it. They were not exposed to English songs, but I’ve added a few English songs to widen their repertoire.

Melantha Perera: Invented a notation

system for the guitar

“On 7th June, we are opening up for the public to come and witness their talents, and I want to take this product island-wide, giving the message that we can do it, and I’m hoping to create a database so there will be a following. Initially, we would like your support by attending the show.”

Melantha says he didn’t know what he was getting into but he had confidence teaching anyone music since he has been in the scene for the past 45 years. He began teaching in 2015,

“When I opened my music school, Riversheen School of Music, the most challenging part of teaching was correcting tone deaf which is the theoretical term for those who can’t pitch a note, and also teaching students to keep timing while they sang and played.”

Melantha has even invented a notation system for the guitar which he has named ‘MelaNota’. He has received copyrights from the USA and ISO from Australia, but is yet to be recognised in Sri Lanka.

During Covid-19, Melantha showcased MelaNota online and then it was officially launched with the late Desmond De Silva playing one of his tunes, using MelaNota.

Melantha says that anyone, including the visually impaired, can play a simple melody on a guitar, within five minutes, using his notation system.

“I’ve completed the system and I’m now finalising the syllabus for the notation system.”

Melantha has written not only for the guitar, but also for drums, keyboards, and wind instruments.

For any queries, or additional information, you could contact Melantha at 071 454 4092 or via email at thebandbrightlight@gmail.com.

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoKiller made three overseas calls while fleeing

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSC notices Power Minister and several others over FR petition alleging govt. set to incur loss exceeding Rs 3bn due to irregular tender

-

Features5 days ago

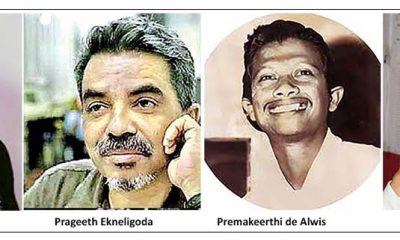

Features5 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoExcellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoMahinda earn long awaited Tier ‘A’ promotion

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMobile number portability to be introduced in June