Features

Smoky experience…for Gypsies

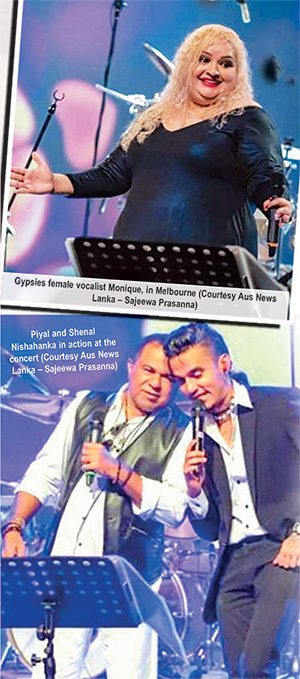

The past few weeks, the popular Gypsies have been very much in the news, very specially for their skill in what they do, on stage, to entertain music lovers.

The past few weeks, the popular Gypsies have been very much in the news, very specially for their skill in what they do, on stage, to entertain music lovers.

Yes, that was the scene, Down Under, when they went into action, on February 9th, in Melbourne, Australia, with a concert and dance.

According to reports coming my way, both events were well patronised, and a total success.

A Sri Lankan, who now resides in Melbourne, and a very keen reader of The Island, checked out the concert and said it was simply fabulous.

“Everyone present loved the music the Gypsies dished out, and we all had a great time.”

He went on to say that the crowd was very much impressed with the new-comer to the Gypsies scene, Shenal Nishahanka.

‘His stage act is absolutely fantastic,” he added.

Shenal, in fact, is a rocker who can sing baila, too, and play the guitar, as well.

And when it was all over, and the Gypsies were ready to head for home, they had a smoky surprise awaiting them!

And when it was all over, and the Gypsies were ready to head for home, they had a smoky surprise awaiting them!

They had boarded SriLankan Airlines flight UL 605 which left Melbourne, heading for Colombo, around 6.15 pm on Monday, 12th February.

Everything was fine, on board, said Piyal, but 30 minutes into their flight a smoke issue cropped up where passengers saw and smelt smoke in the cabin, and also coming from the cockpit, at which stage the Captain announced that they have to circle back to Melbourne and make an emergency landing.

“Although the aircraft circled in the sky for about an hour before making an emergency landing, everyone was calm and the Gypsies were quite cool, as well,” said Piyal, adding that there were emergency vehicles stationed when they landed.

The Gypsies were accommodated in a hotel close to the airport, but they had to rough it out where clothes were concerned.

“We had with us only the clothes we were wearing, to board the flight. The rest were all packed and in the aircraft.

“Our stay at this hotel was fun as we were all dressed up as Kung fu fighters!

“Yes, let’s say our first trip to Australia, with our new lineup, was quite eventful.”

Features

2025: The Year We Let It Happen

“I was saved by God to make America great again,” Donald Trump said, a line that circulated widely during his political comeback rallies. “The golden age of America begins right now,” Trump declared as he was inaugurated for a second term on 20 January 2025, marking a major shift in US politics with consequences likely to extend across generations. Trump’s appeal lay not in moderation but in confrontation, rooted in the assertion that democracy works best when it produces winners unencumbered by restraint. He rewarded many who delivered him power, while leaders in other democracies often spent their mandates managing survival and retreating from pledges once deemed non-negotiable. The old Marxian line about history repeating itself as tragedy and farce felt newly apt as elections continued to produce both at once.

While deteriorating democratic systems grappled with their contradictions, quasi-democratic and openly authoritarian administrations pursued power with less ceremony. Beijing tightened its hold over Taiwan, Tibet, and Hong Kong while projecting its global power with mixed success, and Moscow prosecuted its war in Ukraine with brutal persistence, accepting sanctions and isolation as the cost of imperial memory. The EU’s plan to use frozen Russian funds for Kyiv stalled and was replaced by a €90 billion loan package, which will cost taxpayers around €3 billion annually in interest. Pyongyang continued its missile testing, while its state-linked hackers reportedly stole an estimated $2.02 billion in cryptocurrency in 2025 alone. Tehran, for its part, passed another turbulent year, marked by a 12-day military confrontation with Israel in June 2025 that inflicted significant damage on both countries. Power in these systems remained centralized and unapologetic, justified by security and sustained by fear.

Across the globe, 2025 witnessed a wave of Gen Z-led protests that challenged authority and disrupted the social order in ways reminiscent of the Arab Spring, yet carried their own perils. From climate strikes in London and Berlin to anti-corruption demonstrations in São Paulo, Mexico City, Dhaka, and Kathmandu, young activists confronted entrenched elites with unprecedented energy and digital coordination. In Morocco, Madagascar, Tunisia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, student-led and youth-driven uprisings rattled governments, while in the United States, marches over climate action and student debt repeatedly clashed with authorities.

Even in authoritarian countries such as Iran, Vietnam, and, to some extent, Thailand, clandestine movements mobilized online and in the streets, forcing concessions while provoking brutal crackdowns. Yet these eruptions of youthful revolt, as electrifying as they were, revealed a dangerous pattern: like the Arab Spring, the protests often destabilized societies without delivering durable reform, leaving governments weakened, institutions strained, and political vacuums that could be exploited by opportunistic elites. The Gen Z moment in 2025 was a showcase of idealism and impatience, but also a warning that the seductive energy of revolt can become the architect of new disorder and unfulfilled promise. The question remains: who will have the last laugh?

The dissonance between public display and private conclave became starkly visible in Beijing in September 2025 during the 80th-anniversary commemorations of the end of the Second World War. State television followed Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin as they approached the parade ground, and microphones accidentally left live picked up a fragment of conversation that ricocheted around the world. According to reports, Putin’s interpreter was heard saying, “Human organs can be continuously transplanted. The longer you live, the younger you become,” to which Xi replied, “Some predict that in this century humans may live to 150 years old.”

The Kremlin later confirmed the exchange, insisting it was a casual discussion about medical advances, not a policy statement. Yet the symbolism was hard to miss: two leaders whose authority rests on longevity speculating, however lightly, about defeating mortality itself. In a century marked by demographic decline in both Russia and China, the fantasy of extended life carried political weight.

That moment intersected with a broader obsession that cut across systems: the promise and threat of artificial intelligence. Governments unable to agree on climate targets found common urgency in machine learning, particularly its military and medical applications. The United States National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence warned in 2021 that AI would “accelerate the speed of warfare beyond human comprehension”. By 2025, the Pentagon had embedded AI across military operations, deploying commercial models and prioritizing generative tools to maintain America’s technological edge.

Project Stargate, a high-profile initiative with commitments from OpenAI, Microsoft, Nvidia, Oracle, and SoftBank, was said to involve hundreds of billions of dollars in public-private investment to expand AI infrastructure and research across sectors. In parallel, China’s state and corporate ecosystems together channeled tens of billions into AI development, sustaining the world’s second-largest cluster of AI firms and an expanding suite of generative tools. Critical minerals remained a strategic fulcrum, with China controlling more than 90 per cent of global rare-earth processing capacity and wielding that dominance as leverage over technology and defence supply chains.

Space in 2025 saw competition in orbit intensify rather than abate. The number of active satellites in low Earth orbit surpassed 9,350, led by SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, which accounts for the largest share of operational spacecraft. The Space Development Agency awarded US$3.5 billion in contracts for 72 new infrared tracking satellites to strengthen missile-warning and defence architecture. China’s on-orbit presence also expanded markedly in 2025, with Beijing conducting a record number of launches and placing hundreds of satellites into space to advance communications and surveillance networks, including early deployments for its ambitious Guowang low Earth orbit mega constellation. Close encounters between Chinese, Russian, and Western satellites exposed weak space-traffic coordination, with orbit increasingly framed in martial rather than peaceful terms.

On the ground, the uglier side of power refused to remain hidden. In the United States, the Epstein Files Transparency Act compelled the Department of Justice to disclose federal records by mid-December, but heavy redactions and omissions drew bipartisan criticism from lawmakers who argued the release undermined the law’s intent and shielded powerful individuals. Thousands of pages referenced disturbing allegations and reinforced a widely held sense that wealth and influence can insulate the well-connected from scrutiny or accountability. Elsewhere, established democracies continued to confront systemic failures: France grappled with unresolved clerical abuse scandals; Britain faced renewed criticism over policing gaps in handling grooming gangs; and India’s chronic under-reporting of sexual violence remained a persistent human rights concern.

Meanwhile, the language of peace was deployed with similar cynicism. Trump repeatedly suggested he deserved the Nobel Peace Prize, citing what he described as a series of peace initiatives in which he claimed to have played a decisive role. These included the Abraham Accords of 2020, which normalized relations between Israel and several Arab states, and the 2025 United States-brokered ceasefire in Gaza, under which all remaining living Israeli hostages held by Hamas were released and hostilities were paused through a phased arrangement.

Trump further asserted that his administration had “settled” or eased a widening range of conflicts, pointing to diplomatic efforts aimed at initiating talks towards a negotiated end to the Russia–Ukraine war, although substantive peace terms remain elusive and negotiations continue amid resistance from Kyiv, Moscow, and key European Union states. He also publicly referenced conflicts or diplomatic tracks involving India and Pakistan; Thailand and Cambodia; Kosovo and Serbia; the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda; Israel and Iran; Egypt and Ethiopia; and Armenia and Azerbaijan as evidence of his claimed peacemaking credentials, despite the absence of durable or comprehensive peace settlements in any of these cases.

Trump did not receive the Nobel Prize, whose awards have often favoured aspiration over results. Instead, it went to María Corina Machado, a Venezuelan opposition leader who told me in 2020 that “a mafia group has destroyed my beloved nation, Venezuela”, and whom Washington now treats as a key ally. Meanwhile, the United States has reportedly sought to seize another oil tanker linked to Caracas while pursuing an alleged drug cartel, amid claims that the Secretary of War ordered forces to “kill them all”. At the same time, Latin America has seen a significant rise in right-wing politics, with Argentina’s Javier Milei consolidating power, Chile electing far-right leader José Antonio Kast, and conservative presidents such as Daniel Noboa in Ecuador and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador gaining influence amid broader regional shifts to the right.

Africa was not immune to global disorder. In Sudan, a brutal civil war between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and rival factions continued throughout 2025, marked by repeated mass atrocities, including ongoing killings around El Fasher in North Darfur that left tens of thousands dead and displaced millions, making it one of the world’s most devastating humanitarian crises. The United Nations and humanitarian agencies reported widespread executions, sexual violence, and attacks on civilians and health facilities. Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, fighting between the Congolese army and the Rwanda-linked M23 rebel group forced thousands to flee, with more than 84,000 refugees crossing into neighbouring Burundi in 2025.

Nigeria’s security situation also deteriorated, with jihadist factions, including Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province, expanding operations and causing civilian casualties and displacement. Across West Africa, political realignment followed coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, which jointly withdrew from ECOWAS and formed the Alliance of Sahel States, commonly dubbed the “African NATO”. The bloc has announced plans to establish a shared central bank and investment fund aimed at economic autonomy and reducing reliance on traditional financial systems, but it remains too early to assess its capacity to curb the continent’s growing Islamic extremism and militant gangs.

Through all this, inequality hardened. The latest World Inequality Report 2026 showed that the richest 0.001 per cent of adults — fewer than 60,000 individuals — now control three times more wealth than the poorest half of the global population combined, while the richest 10 per cent own around three-quarters of global wealth. While leaders speculated about extended lifespans and investors poured money into longevity start-ups, life expectancy stagnated or fell in several countries: in the United States it remained lower than a decade earlier, and in parts of sub-Saharan Africa gains were erased by conflict and weak health systems.

Orwell’s line continues to resonate, even at the risk of banality: “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” The events of this year have not disproved it; they have updated it with satellites, algorithms, and offshore accounts. Power now moves faster and hides better, but it still feeds on the same asymmetries. As another year closes, the temptation is to wish for renewal without reckoning. That wish has become a luxury. The facts are stubborn: inequality widens, wars persist, technology accelerates without consensus, and leaders speak of salvation while tolerating cruelty. New Year greetings sound hollow against that record, but perhaps honesty is a start. The age we are entering will not be golden by proclamation; it will be judged, as ever, by who is allowed to live with dignity — and who is told, politely or otherwise, to wait. To the New Year — hopefully wiser.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa ✍️

Features

After Christmas Day

We are in this period – the days immediately following Christmas – December 25. The intense religious and festive two days are over, but just as the festive season precedes Christmas Day, it follows it too, notwithstanding the day that marks the beginning of the new year.

Christmas is significant, I need not even mention, as the celebration of Jesus Christ’s birth in Bethlehem in a manger as there was no room at the inn. It however symbolizes God‘s love and salvation for his ‘children’. People make merry with traditional gift giving (custom from the three kings), carols, bright lights concentrated in indoor fir trees and general goodwill epitomized by jolly old Santa. It is also a time of spiritual reflection on God’s love of people by his giving his son to their will.

The day after Christmas – 26 December – is also a day marked in the calendar of the festive season. Named Boxing Day, it too is a holiday of fun. Originally a day of generosity and giving gifts to those in need, it has evolved to become a part of Christmas festivities. It originated in the UK and is observed by several Commonwealth countries, including Ceylon.

It is concurrent with the Christian festival of Saint Stephen’s Day, which in many European countries is considered the second day of Christmas. It honours St. Stephen who was the first Christian martyr who was stoned to death for his faith. More commonly, it is called Boxing Day, also known as Offering Day, for giving servants and the needy gifts and financial help. The term boxing comes from the noun boxes, because alms were collected in boxes placed in Churches and opened for distribution on the day after Christmas. This day is first mentioned in the Oxford English Dictionary on 1743.

The Twelve Days of Christmas follow the 25th and make up the Christmas Season. It marks the days the kings of Orienta –Magi – took to visit the infant Jesus with gifts of gold, myrrh and frankincense, symbolizing Christ’s royalty, future suffering and divinity/ priesthood respectively.

The “Twelve days of Christmas” we know as a Christmas carol or children’s nursery rhyme which is cumulative with each verse built on the previous verse. Content of the verses is what the lover gives his /her true love on each of twelve days beginning with Christmas day, so it ends on January 6, which marks the end of the Xmas season. The carol was first published in England in the late 18th century. The best known version is that of Frederic Austen who wrote his rhymes in 1909.

“On the first day of Christmas my true love sent to me

A partridge in a pear tree.

On the second day of Christmas my true love sent to me

Two turtle doves

And a partridge in a pear tree.”

And so on with three hens, four calling birds; five gold rings, six geese a-laying, seven swans a-swimming, eight maids a-milking, nine ladies dancing, ten lords a-leaping, eleven pipers piping, twelve drummers drumming. But the most important fact is that each animal or human represents a Christian object or key tenet of the faith, serving as a religious tool where each gift depicts a religious concept.

For instance, it is believed the partridge symbolizes Jesus and two turtle doves represent the Old and New Testaments. Doves are symbols of truth and peace, once again reinforcing the tie to Christ and Christmas. Reference is also made to the Ten Commandments, the 12 Apostles and the Creed. However, this is a popular theory and not a historic fact with some believing it is a love song pure and simple.

And so 2025 draws to an end. One cannot but throw one’s thoughts back to when one was an eager beaver child. Buddhist though I was, I attended a Christian school from Baby Class and was very influenced by the Christian faith. In fact, an older sister was so indoctrinated she wanted to convert to Christianity. Our Methodist missionary school did not encourage conversions.

Mother was unaware of this great attraction; her emphasis was on an English education for her children,. But being so drawn to the Christian religion with all its celebration and merriment was no surprise, added to the fact that Vesak was such a solemn occasion with sil redi restraint and the death of the Buddha too commemorated.

It is a very heartening fact that in this country Buddhists too join in the pleasures of Christmas. Many go for Midnight Mass on 24th because of religiously mixed marriages or merely to enjoy that experience too. Our family, when the children were young, invariably celebrated with the traditional XMas tree in the house with my husband taking great pleasure in buying a branch of a cypress tree sold in Colombo, and decorating it. We often spent the holiday in Bandarawela and so Christmas became extra special with the strong smell of the tree branch bought indoors. Santa visited my young one for long years; he being a strong believer in the delightful myth.

Delightful memories are made of these…

I wish everyone a wonderful Christmas. Let’s substitute the sorrows and despair of the aftermath of the cyclone and give ourselves, all Sri Lankans, a break and renew our togetherness and one-ness as a nation of decent people..

Features

Disaster Management and The Power of Science

The key to managing future disasters is through the smart utilisation of science

Living With Nature

As Sri Lanka has witnessed through the intense impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah, the power of nature is there for all to see, feel, hear, and grieve over. The hubris of humanity deludes us. We cannot control nature in its most powerful manifestation. The lesson we should learn is to live with nature, listen to nature, and learn from nature. The most effective method of managing disasters, mitigating disasters, or even avoiding disasters is to smartly apply the science that is readily available to all. Smart science utilisation educates all about the magnitude, scale, duration and likely outcomes of natural phenomena. This approach feeds into developing a culture of living with nature, planning our country with nature in mind, training the scientists we need, strengthening scientific and disaster management departments and institutions, joining up decision makers and scientists, and dramatically increasing the scientific awareness of the whole population. This is a sure-fire way of reducing the devastation of potential disasters. BUT: it’s a hard road, a difficult road, and one that requires the sustainability of a safe nation focus, decade after decade. This article focuses briefly on the science of cyclones/storms, rivers, and landslides: the three natural phenomena that bring the most frequent disasters to Sri Lanka.

Worldwide Cyclone Paths

Bay of Bengal Cyclone Paths

Tropical Cyclone

Tropical Cyclones originate between latitudes 10 degrees north and south of the equator. They form through heat interactions of warm surface ocean waters and the atmosphere. Cyclones move from the equator to the north and south, seeking the warmest parts of the ocean to sustain and build their formation. Cyclones are heat-seekers and can only survive while warm surface ocean waters continuously feed intense convection systems that create enormous spiral clouds rotating around a central column. Thankfully, most cyclones are born and die harmlessly within ocean space. But when they make landfall they release their pent-up energies in the form of winds, rain, and storm surges (oceans can be sucked up like tsunamis by intensely low-atmospheric pressures associated with cyclones). The most powerful cyclones generate winds of 300 to >400km/hour, air pressures as low as 870mb, total rainfalls of over 6m, and highest rainfall intensities of 1.14m/24 hours and >400mm/hour. Cyclones mainly affect countries located between latitudes 10 and 30 degrees north and south of the equator. Regions such as East Asia, the Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico and Indian/Pacific Ocean Islands are the most impacted cyclone areas. Sri Lanka is lucky, as relatively few cyclones make landfall, tending to move further north before they strike.

Cyclone Ditwah and Sri Lanka

Cyclone Ditwah was rapidly born SW of Sri Lanka, growing from a meteorological depression on the 26th of November 2025. It moved east and north crossing Sri Lanka over the next few days, retaining a low-pressure identity until December 3rd. It formed through the presence of warm ocean around Sri Lanka and concurrent atmospheric conditionalities.

Rainfall Over Sri Lanka 27-29 November 2025

The slow-moving nature of Cyclone Ditwah significantly increased its impacts. As cyclones go, wind speeds were on the low side (50-90km/hour) and the air pressure relatively high (1002 mb). Ditwah did, however, release large amounts of rainfall over 2-3 days of protracted rainfall, and over large areas of Sri Lanka. Total rainfalls of 150-500mm occurred alongside rainfall intensities of 300mm/24 hours. A similar slow-moving tropical depression hung around the mountains of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, for several days during April 2014, releasing over 700mm of rainfall, which created severe flooding in the national capital town of Honiara.

Storms and Monsoons

Cyclones are examples of extreme storms. Storms are a more frequent and regular weather phenomenon within Sri Lanka. Whatever label is given to weather systems the important data we need for managing rain hazards includes the timing and duration of storms, their predictability, the earliest warning signs we can detect, likely wind speeds and durations, rainfall amounts and distribution, and areas most likely to be affected by storms.

Sri Lankan Monsoons

Sri Lanka’s meteorological patterns are well known and documented by the SL Department of Meteorology and other sources. The drivers, durations, weather patterns, and areas affected by the two monsoons (from the southwest and northeast at different times of the year) are common knowledge. Furthermore, incidents of disasters caused by intense storms have produced a plethora of data that can be used to inform disaster management and planning. The science of meteorology has been revolutionized over the past decades through the advent of sophisticated satellite, airborne, and ground weather sensors, alongside big-data multiple-scenario mega-computer modelling capabilities, and an abundance of highly trained meteorological scientists. The recognition of climate change, particularly since the late 1990s, has led to a quantum leap in in research and financial investments, and hardware/software/ scientific advances. We now know our weather systems and the physics of the atmosphere with an enviable level of prediction/modelling when viewed through the eyes of the 1960/70s or 80s generations

Whither the Weather Data: what’s the Point?

There is no substantial reason or excuse why countries, regions, communities, scientists, and decision-makers cannot turn all the amazing weather data and capability into tools and practical applications to mitigate future disasters. The science is so smart and powerful that a failure to use its helpful essence is plain foolishness. The data, and approach suggested, as we will see below, with river and landslide science, can undoubtedly deliver a safer country and world. Bangladesh, a poor country with a population of 172 million is regularly hit by cyclones, storms. and high magnitude floods. Cyclone Bhola, in 1970, killed half a million people and wiped out 85% of the nations homes. And yet, this low-income nation has impressively adopted new smart disaster management ways, including integrating science, greatly reducing the impacts of disasters over time.

Allowing Rivers to Run Free

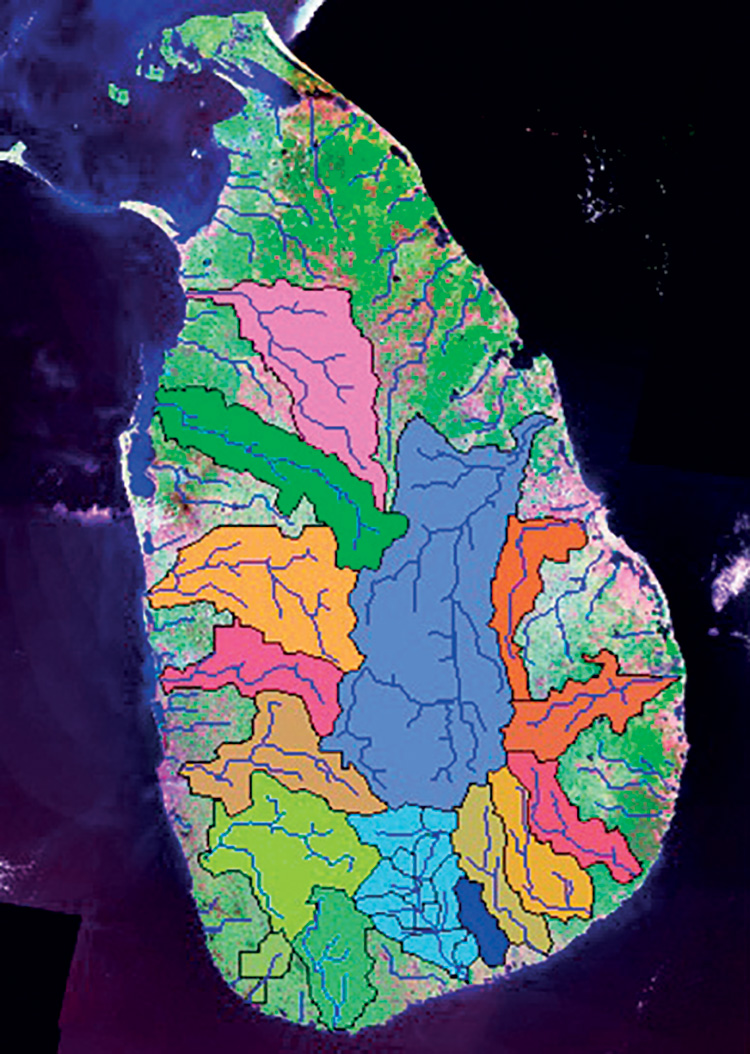

Sri Lanka River Basins

Sri Lanka has over 100 river basins, (or catchments), the largest of which (the Mahaweli) has an area of over 10,000km2. The Mahaweli River extends to over 335 km in length. Sri Lankan rivers are mostly aligned in a radial fashion, centred upon South-Central Highlands, flowing to all corners of the country. Rivers are the lifeblood of any country. They are like blood vessels in the human body. If we fail to look after rivers, environments degrade, human and animal life suffers, and disasters are heightened in magnitude.

Modern (and ancient) philosophers ask us to view rivers not as inanimate natural features, but as sentient living beings. The science of hydrology (study & understanding of water systems) enables humans to optimally manage rivers and related eco-landscape systems, and to live safely with rivers. The latest thinking is moving towards the idea of allowing rivers to run freely: for humans to adopt the principle living respectfully and safely with the vital lifeblood of any country or region.

Rivers form through rain (and snow) falling on land and organising themselves according to the physical laws of drainage. Just as we engineer drainage in our houses so that we stay dry, and channel the waters where we want them to go, nature drains our lands. Rivers will follow the easiest path they can from the highest areas of their river basins (or catchments) to the lowest point they can reach (usually the ocean, sometimes local lakes or inland seas). Rivers follow geology and topography, but also mould and shape landscapes themselves, over time.

- Landslide Prone areas in Sri Lanka (Source Geosciences Research 2018, Bandara & Jayasingha)

- Sri Lanka River Basins (Source https://island.lk/eco-friendly-regional- development-model)

They are fed from water reservoirs that come from the sky, from vegetation root systems, and from large underground reservoirs. Geological structures, geological bedrock and geological surface deposits all influence rivers. Gravity will dictate how water flows through any landscape.

The nature of rivers changes according to the quantity and rate of water they transport. During times of low rainfall and drought they will occupy only a small part of their channels. With heavy and intense rain, they rise and often break out of their channels flooding their hinterland (termed floodplains). The rise and fall of rivers are natural. When rivers are at their highest their sheer hydraulic power is thousands of times greater than during the quiet times. Floods have provided humans with fertile plains, regularly renewing land with fresh silt and mud, and the sapphires, garnets, and rubies Sri Lanka is famous for. Science allows us to deeply understand the nature and behaviour of rivers: why they occupy their courses, why they go dry, why they flood, how much they flood, how they erode, how they deposit, and how they can carry different sizes and volumes of material.

Modern scientific sensors can accurately map rivers, measure the rainfall within their catchments, their flow rates, and the shape and form of their river channels. Modern computer modelling can accurately predict the size, duration, time, magnitude, and likely impact of floods. Mapping of geological river deposits informs us of the extent of floods over time in any river system. Science can monitor rivers, inform us about groundwater reservoirs and health, pollution within rivers, and how human impacts are influencing river processes.

Most rivers in the world have been engineered by humans in a wide variety of ways. Dams, canals, river re-routing, energy generation, water storage, water pumping schemes, irrigation, and industrial utilisation, are examples. Intelligent utilisation of river resources has been of great human benefit. However, as with any natural system, there is a threshold beyond which damage is caused to the arteries of the nation. River catchment (basin) development can occur with no mindfulness of river-health. Mountainsides are denuded of trees, houses and urban areas grow quickly with disregard to river-natures, the natural architecture of land and river drainage is altered so much that water run-off significantly increases, and the impact of floods increases dramatically.

Whilst humans must use river resources to sustain modern livelihoods, the wider utilisation of science to inform our activities, and the greater the adoption of the principle of allowing rivers to run free, the safer our world will be. Our rivers and ecosystems will smile widely. Simple science-informed guidance such as avoiding building houses in flood plains, caring for the slopes that feed our rivers, and limiting rapid water urban run-off can be adopted by all. The idea of ‘sponge’ cities where urban environments soak up and store water, rather than increasing run-off is catching on in Singapore, China, and Denmark.

Sri Lanka’s population growth 1871 – 2001 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SL_population_ growth.png)

Carefully safeguarding, and maximising the anti-flood control potentials of the beautiful wetland network of Colombo, and the incredible intelligent irrigation systems built from over 2000 years ago in central-north Sri Lanka is essential for a future safe Sri Lanka.

The Science of Landslides

Landslides occur in different shapes and forms but essentially move material quickly downslope through the force of gravity. They can vary in size, style, and magnitude, from slow but persistent peripheral movement of surface layers, to rapid movement of large quantities of rock and surficial deposits over significant distances. One large recent earthquake in Enga province, Papua New Guinea (2024) formed from the collapse of a large part of a mountainside, burying villages and leading to the deaths of up to 2000 people. Some of the world’s largest landslides transport cubic kilometres of material, and have killed 20,000 – 200,000 in China, Venezuela, and Peru.

Landslide Prone areas in Sri Lanka

Sri Lankan landslides mostly occur within the central Highlands region and peripheral areas, particularly in the southwest.

Much of Sri Lankan geology is comprised of hard crystalline rocks called gneiss: this forms the bulk of the nation’s upstanding mountains. Whilst intrinsically a hard and strong rock, Sri Lankan gneisses are weathered deeply by a hot, humid, tropical climate. Chemical weathering breaks down bedrock, forming thick deposits of altered degraded, material, termed regolith. These deposits can be 10m-> 30m thick. They lack the intrinsic cohesive strength and structure of the gneissic bedrock from which they form. Regolith is often reddish in colour due to the presence of abundant iron hydroxides.

Debris Flow Rotational Landslide

Sri Lankan landslides are mostly termed debris flows, involving the rapid downslope movement of moderate to large volumes of surficial regolith material downslope.

The causes of landslides are well known, as are areas of landslide high-risk. Landslides occur on steep or moderate slopes, particularly within areas of high relief. Triggers for landslides include earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and high intensity rainfall. For Sri Lanka heavy rainfall, persistent rainfall, or alternating protracted periods of heavy and/or persistent rain with contrasting drought seasons are the main landslide triggers. Persistent-protracted monsoonal rainfall can seep deeply within surface regolith material, particularly if the materials are porous and permeable (capable of soaking and transporting water within its mass, like a sponge).

When the regolith becomes sodden with water its weight increases many times, internal friction is reduced, and lubrication increased. The ever-present gravity pulls with greater force on this wet, heavy, lubricated regolith. When this gravitational force exceeds the ‘sticking’ force that binds the regolith to the mountainside, the material slips and forms a landslide. Ancient and recent landslide deposits can be geologically mapped, helping us understand where and why landslides have occurred in the past. This mapping helps us identify and locate high-risk zones. Slope strength can be monitored through slope-stress sensors. In Hong Kong, a city of millions built on steep tropical slopes, every high-risk slope is catalogued, drained of water, strengthened through engineering, and regularly monitored.

Human activities can significantly increase the risks of landslides. Any activity that reduces the stability of slopes increases the probability of landslides. Cutting down trees, steepening slopes through engineering, and retarding natural slope-drainage, will all increase the likelihood of landslides. Moving human settlement to high-risk zones increases the exposure of people to landslide risks. Human interventions can reduce landslide risks by planting trees with deep root systems on slopes, increasing the natural drainage of slopes, and monitoring slope stability through simple observations such as observing the onset or long-term occurrence of surface cracks, road and wall slippage, and cracks appearing in buildings on slopes.

Increasing urbanisation in Colombo 1995-2017 (Source https://archive.roar.media/english/life/in-the-know/urbanisation-sri-lanka-growing-pains)

Landslides are a natural phenomenon and are part of the beauty of landscape formation. They have occurred long before humans existed and will continue to do so long after humans. The science of landslides is well understood and can help us all live more safely, at lower levels of risk. It is up to us to take notice of nature and live wisely with the nature of landslides.

Demographics and Development

Whilst climate change has had numerous impacts on weather systems, particularly in increasing the capacity of clouds to hold water, and rain more intensely, along with increasing the power of winds, we cannot blame everything on climate change. In days gone by we used to blame gods, now we blame climate change. We need to adapt to climate change, full stop. There are many things we are in control of and can change. More importantly, we need to become increasingly aware of the link between demography, socio-economics, urban development, and increasing environmental risks. These phenomena are all in our hands.

For most of human history global populations numbered millions and tens of millions. By 1804 the global population reached 1 billion, 2 billion during the early twentieth century, almost 3 billion in 1950 and now over 8 billion. This rapid rise in population, together with unprecedented levels of consumerism, has stressed the earth far more than any living species has done so during the past 4 billion years.

Sri Lanka’s population growth 1871 – 2001

Sri Lanka’s population grew rapidly from 2 million in1871, 6 million in 1943, to 22 million today, although it now appears to be reaching a steady state. This rapid population growth has led to concomitant urban growth, particularly around Colombo and the southwest, together with road-ribbon development, virtually continuously for example, between Colombo and Kandy. Mass tourism adds another one or two million high- consuming visitors every year.

Increasing urbanisation in Colombo 1995-2017

Rapid, sub-optimally planned, urban development, not only leads to the rapid generation of less-attractive urban environments (that will deter visitors), but also increases the exposure of a greater number of people to environmental risks. Whilst the power and wisdom of science can produce informed plans for safety and planetary health, the competing power of the development rupee or dollar profit unfortunately wins out. Profit at the expense of nature and environmental safety.

Conclusions: the power of Science: it’s in our hands

This article clearly spells out the practical nature and the power of the science of cyclones, weather, rivers and landslides, and how it can reduce our risks and exposure to potential disasters. Cyclone Ditwah and the 2004 tsunami were clear demonstrations to Sri Lanka of the power of nature. Science informs us, educates us, helps us understand how nature works, devises early warning methods and systems, monitoring tools, and predictive advice. If we apply the science and combine this with decision-makers, government, communities, and industry, we can live with nature and develop towns cities and village sympathetically. This is our choice. It is in our hands. We can avoid placing high populations or vulnerable poor people in areas of high environmental risk. We don’t have to surface this beautiful country with unattractive, never-ending, concrete, plasterboard, and cement. We can, instead, work with natural science, with natural systems, and with nature to create a happier, safer country, in-tune with the non-human as well as the human world.

Honouring all humans and sentient beings who have suffered from Cyclone Ditwah

I express my deep condolences to all who have suffered as Cyclone Ditwah struck. Many died. Many lost their homes, possessions, and loved ones. Many suffered damage to their properties. So many birds animals, insects and sentient beings suffered. Disasters bring deep anguish. Thankfully, the Government, nation, institutions, society and the international community have recognised the level of emergency and are providing assistance in a myriad of forms. I hope that, in a small way, this article presents opportunities to reduce future suffering.

by Prof. Michael G. Petterson

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoAir quality deteriorating in Sri Lanka

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCardinal urges govt. not to weaken key socio-cultural institutions

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoAnother Christmas, Another Disaster, Another Recovery Mountain to Climb

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCID probes unauthorised access to PNB’s vessel monitoring system