Features

Sir Baron Jayatilaka (1864-1944): unique among Ceylon’s great men

(Excerpted from Selected Journalism by HAJ Hulugalle)

Among the great men produced by the country, Sir Baron Jayatilaka was unique. He was the village lad from an obscure family who rose to the top by his own ability and strength of character. He learned his first letters and laid the foundations of oriental scholarship at a temple school, but thereafter obtained a modern education at Wesley College. At 21 he was a graduate of Calcutta University, and twenty years of work and study intervened before he was able to go to Jesus College, Oxford, where he became an M.A.

Jayatilaka was a school-master before he entered the legal profession and a political career. He seemed to take everything in his stride, biding his time, but never lost the respect of those he left behind in the race.

He died 19 years before this article was written, and in this land of short memories, it looked as if he would be forgotten by those who came after him. Nobody suggested a statue of that broad-shouldered and squat figure with a defiant air in times of crisis. His portrait is not to be seen in public places nor is his Roman profile perpetuated in a postage stamp. A street may have been named after him, but I have not heard of it.

In his life Jayatilaka did not need reclame, and in the Elysian fields, or where-ever else he may be, he would be the first to laugh at any efforts to preserve his memory in wood or stone. He would have said exigi monumentum acre perennius (“I have completed a monument more lasting than brass.”)

He seemed to reflect in his life all that is best in our culture, in the Buddhist tradition and in oriental philosophy, and possessed in full measure those gifts and graces which characterize a civilized person such as tolerance, fair-play and compassion.

He had married the very intelligent and charming daughter of a great scholar. Their home, where they lived simply and modestly, was an intellectual centre for men of learning. Long before “D.B.” became a member of the Legislative Council he was the leading Buddhist layman in the country. His influence on the priesthood of all the Nikayas was decisive, for in scholarship and personality he was the equal of the best among them. He was president of the YMBA as long as he lived. His editions of the Sinhala classics are prized by other scholars. His articles in the Dinamina made that paper the leading Sinhalese daily.

There were times when he took his courage in his hands and fought for unpopular causes, It was touch and go whether the Legislative Council would accept the Donoughmore reforms. He advised the country to try to work them. Many of his close friends, such as E.W. Perera, were against him, but he carried the day.

He fought for the report of the Akbar Commission on the University site, of which he was a member, against a formidable array which included James Peiris, Ramanathan, Marcus Fernando, George Wille, Marrs (the Principal of the University College) and the hierarchy of two churches, and won. He was a splendid debater and gave as hard as he got. No heckler could have the better of him. On September 20, 1920, at a special meeting of the Ceylon National Congress, he was proposing the main resolution and was interrupted. The report of that meeting has the following passage:

Mr. Jayatilaka: I predict victory for us if we exercise self-restraint and moderation….

A Voice: Cowardice?

Mr Jayatilaka: I am prepared to accept the challenge from that quarter…. A Voice: Cowardice.

Mr Jayatillaka: I challenge that gentleman to get up and say where he has shown bravery which I have not been equal to. (Tremendous applause which prevented Mr. Jayatilaka from continuing for several seconds).

Mr. A.E.Goonesinha: We never meant it for you. We acknowledge you as the greatest man who has come forward. When we spoke of…..

Mr.Jayatilaka: It is only a distinction without a difference.

As a young journalist whose business it was to interview leaders of the reform movement, I first met D.B. Jayatillaka in 1918. Not being a Buddhist or a Sinhalese scholar myself, the occasions when I came into close contact with him were few, but from the outset I was an admirer. He possessed not only the qualities of a statesman but also the courage of a leader. He had intellectual honesty and refused to play down to the masses. He stood for national unity.

I remember his presidential address to the 1924 Congress when he said: “if we are determined to attain responsible government we must bestir ourselves and bring about that condition of national unity that is indispensable for the realization of our goal. Full responsible government can only be demanded by and granted to a united people”. I doubt whether he would have become a politician if he did not believe in national unity. He would have felt betrayed had his successors thought otherwise.

Jayatilaka began his public life in the temperance movement, but education was his major interest. In both these fields he was the associate of men with high ideals like Colonel Olcott, the Ven. Hikkaduwa Sri Sumangala, Anagarika Dharmapala, W.A. de Silva, Arthur V. Dias and the Senanayakes. He spent 20 years guiding the destinies of Dharmaraja College and the Buddhist Theosophical Society. It was as a result of these activities that he was arrested and kept in prison for 46 days during the 1915 riots. He tasted injustice but it did not embitter him.

The fight for political reforms began in earnest when the country’s leaders decided that never again will such arbitrary action by the military be permitted. Jayatilaka made many journeys to London to press for reforms and impressed Lord Milner, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, and his officials, by his moderation and good sense.

In 1924 he was elected unopposed to the Legislative Council as the member for the Western Province. Very soon he was the unofficial leader of the Council, and when the Donoughmore Constitution was introduced in 1931 he became Leader of the House, Vice-President of the Board of Ministers and Home Minister. He held these offices for 10 years.

Although Jayatilaka never lost the mastery of the State Council, when he reached his seventies he had lost a great deal of his fire. He was easy-going and lenient. He had lost the sureness of his touch, and signed papers which he had not read. His ability to see both sides of a question was not appreciated by contestants for power. He was the Asquith of Ceylon politics, a noble mind ill at ease in an atmosphere of intrigue and tension.

The mistakes he made were often the result of manoeuvring by others when he himself was too old to play political chess. The Bracegirdle affair was a ludicrous interlude, and the pan-Sinhalese Board of Ministers was a foolish move, both out of character with the elder statesman.

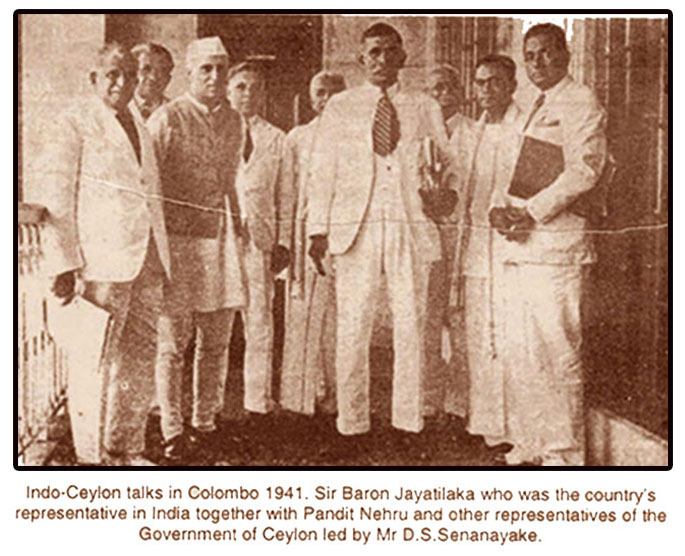

He resigned in 1940 to become the first Ceylon representative in India, a country in whose culture and history he was deeply interested. No one could have represented Ceylon better, but it seemed as if he had been kicked upstairs by more dynamic men. The extremes of the Delhi climate did not suit him and he kept bad health. He died in the aeroplane which was bringing him back to Ceylon. There was perhaps no more appropriate way for a great Buddhist to attain Nirvana but he would not have minded an honoured and leisured retirement on earth to round off his career and arrange his papers. It is given to few mortals to order their exits and entrances suitably.

Many eloquent tributes were paid to Sir Baron in the State Council when a vote of condolence was moved. His doughty opponent Mr. G.G. Ponnambalam summed up his qualities when he said: “Mr. Speaker, there might have been, individually, a greater scholar, a greater administrator or a greater politician. But in the remarkable combination of qualities of scholarship, of statesmanship and erudition, I think Sir Baron will not be easily surpassed in the future. He was a happy blend of eastern culture and western poise”.

A man like “D.B.” would probably be a misfit in the political scene of today. We are all socialists now. His work was over when he succeeded in bringing Ceylon to the threshold of independence. His thinking and actions helped to shape events in Ceylon for half a century. The ethos of our people was embodied in his life and work more than in those of any other man of the century.

Features

The State of the Union and the Spectacle of Trump

President Donald J. Trump, as the American President often calls himself, is a global spectacle. And so are his tariffs. On Friday, February 20, the US Supreme Court led by Chief Justice John Roberts and a 6-3 majority, struck down the most ballyhooed tariff scheme of all times. Upholding the earlier decisions of the lower federal courts, the Supreme Court held that Trump’s use of ‘emergency powers’ to impose the so called Liberation Day tariffs on 2 April 2025, is not legal. The Liberation Day tariffs, which were comically announced on a poster board at the White House Rose Garden, is a system of reciprocal tariffs applied to every country that exported goods and services to America. The court ruling has pulled off the legal fig leaf with which Trump had justified his universal tariff scheme.

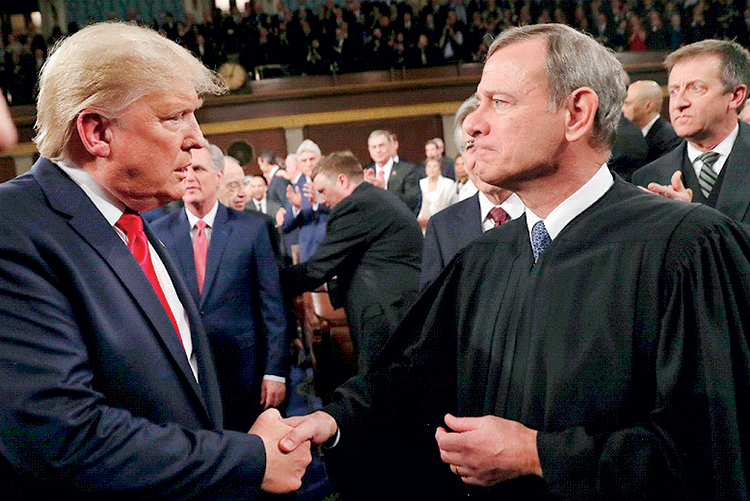

Trump was livid after the ruling on Friday and invectively insulted the six judges who ruled against Trump’s tariffs. There was nothing personal about it, but for Trump, the ever petulant man-boy, there isn’t anything that is not personal. On Tuesday night in Washington, Trump delivered his first State of the Union address of his second presidency. The Chief Justice, who once called the State of the Union, “a political pep rally,” attended the pomp and exchanged a grim handshake with the President.

Tuesday’s State of the Union was the longest speech ever in what is a long standing American tradition that is also a constitutional requirement. The Trump showmanship was in full display for the millions of Americans who watched him and millions of others in the rest of world, especially mandarins of foreign governments, who were waiting to parse his words to detect any sign for his next move on tariffs or his next move in Iran. There was nothing much to parse, however, only theatre for Trump’s Republican followers and taunts for opposing Democrats. He was in his usual elements as the Divider in Chief. There was truly little on offer for overseas viewers.

On tariffs, he is bulldozing ahead, he boasted, notwithstanding the Supreme Court ruling last Friday. But the short lived days of unchecked executive tariff powers are over even though Trump wouldn’t let go of his obsessive illusions. On the Middle East, Trump praised himself for getting the release of Israeli hostages, dead or alive, out of Gaza, but had no word for the Palestinians who are still being battered on that wretched strip of land. On Ukraine, he bemoaned the continuing killings in their thousands every month but had no concept or plan for ending the war while insisting that it would not have started if he were president four years ago.

He gave no indication of what he might do in Iran. He prefers diplomacy, he said, but it would be the most costly diplomatic solution given the scale of deployment of America’s fighting assets in the region under his orders. In Trump’s mind, this could be one way of paying for a Nobel Prize for peace. More seriously, Trump is also caught in the horns of a dilemma of his own making. He wanted an external diversion from his growing domestic distractions. If he were thinking using Iran as a diversion, he also cannot not ignore the warnings from his own military professionals that going into Iran would not be a walk in the park like taking over Venezuela. His state of mind may explain his reticence on Iran in the State of the Union speech.

Even on the domestic front, there was hardly anything of substance or any new idea. One lone new idea Trump touted is about asking AI businesses to develop their own energy sources for their data centres without tapping into existing grids, raising demand and causing high prices and supply shortages. That was a political announcement to quell the rising consumer alarms, especially in states such as Michigan where energy guzzling data centres are becoming hot button issue for the midterm Congress and Senate elections in November. Trump can see the writing on the wall and used much of his speech to enthuse his base and use patriotism to persuade the others.

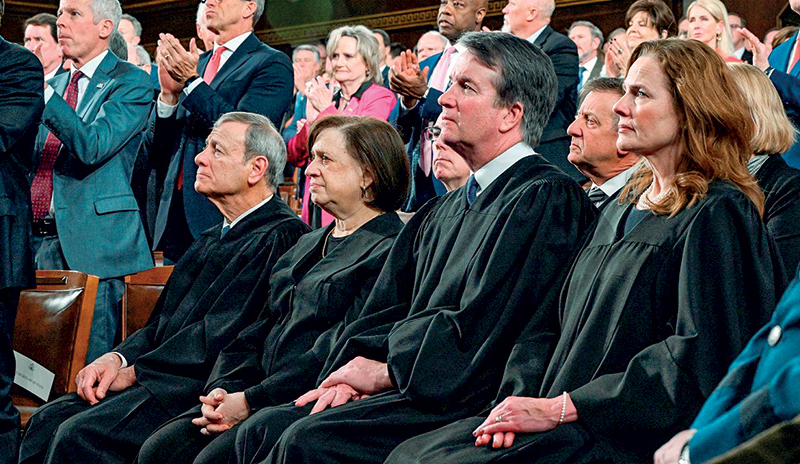

Political Pep Rally: Chief Justice John G. Roberts sits stoically with Justices Elena Kagan, Bret Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, as Republicans are on their feet applauding.

Although a new idea, asking AI forces to produce their own energy comes against a background of a year-long assault on established programs for expanding renewable energy sources. Fortunately, the courts have nullified Trump’s executive orders stopping renewable energy programs. But there is no indication if the AI sector will be asked to use renewable energy sources or revert to the polluting sources of coal or oil. Nor is it clear if AI will be asked to generate surplus energy to add to the community supply or limit itself to feeding its own needs. As with all of Trump’s initiatives the devil is in the details and is left to be figured out later.

The Supreme Court Ruling

The backdrop to Tuesday’s State of the Union had been rendered by Friday’s Supreme Court ruling. Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority ruling was both unassuming and assertive in his conclusion: “We claim no special competence in matters of economics or foreign affairs. We claim only, as we must, the limited role assigned to us by Article III of the Constitution. Fulfilling that role, we hold that IEEPA (International Emergency Economic Powers Act) does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.”

IEEPA is a 1977 federal legislation that was enacted during the Carter presidency, to both clarify and restrict presidential powers to act during national emergency situations. The immediate context for the restrictive element was the experience of the Nixon presidency. One of the implied restrictions in IEEPA is in regard to tariffs which are not specifically mentioned in the legislation. On the other hand, Article 1, Section 8 of the US Constitution establishes taxes and tariffs as an exclusively legislative function whether they are imposed within the country or implemented to regulate trade and commerce with other countries. In his first term, Trump tried to impose tariffs on imports through the Congress but was rebuffed even by Republicans. In the second term, he took the IEEA route, bypassing Congress and expecting the conservative majority in the Supreme Court to bail him out of legal challenges. The Court said, No. Thus far, but no farther.

The main thrust of the ruling is that it marks a victory for the separation of powers against a president’s executive overreach. Three of the Court’s conservative judges (CJ Roberts, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett) joined the three liberal judges (all women – Sonia Sotomayor, Elana Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson) to chart a majority ruling against the president’s tariffs. The three dissenters were Brett Kavanugh, who wrote the dissenting opinion, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett were appointed by Trump. Trump took out Gorsuch and Barrett for special treatment after their majority ruling, while heaping praise on Kavanaugh who ruled in favour of the tariffs. Barrett and Kavanaugh attended the State of the Union along with Roberts and Kagan, while the other five stayed away from the pep rally (see picture).

The Economics of the Ruling

In what was a splintered ruling, different judges split legal hairs between themselves while claiming no special competence in economics and ruling on a matter that was all about trade and economics. Yale university’s Stephen Roach has provided an insightful commentary on the economics of the court ruling, while “claiming no special competence in legal matters.” Roach takes out every one of Trump’s pseudo-arguments supporting tariffs and provides an economist’s take on the matter.

First, he debunks Trump’s claim that trade deficits are an American emergency. The real emergency, Roach notes, is the low level of American savings, falling to 0.2% of the national income in 2025, even as trade deficit in goods reached a new record $1.2 trillion. America’s need for foreign capital to compensate for its low savings, and its thirst for cheap imported goods keep the balance of payments and trade deficits at high levels.

Second, by imposing tariffs Trump is not helping but burdening US consumers. The Americans are the ones who are paying tariffs contrary to Trump’s own false beliefs and claims that foreign countries are paying them. 90% of the tariffs have been paid by American consumers, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Small businesses have paid the rest. Foreign countries pay nothing but they have been making deals with Trump to keep their exports flowing.

According to published statistics, the average U.S. applied tariff rate increased from 1.6% before Trump’s tariff’s to 17%, the highest level since World War II. The removal of reciprocal tariffs after the ruling would have lowered it to 9.1%, but it will rise to 13% after Trump’s 15% tariffs. The registered tariff revenue is about $175 billion, 0.6% of U.S. gross domestic product. The tariff monies collected are legally refundable. The Supreme Court did not get into the modalities for repayment and there would be multiple lawsuits before the lower courts if the Administration does not set up a refunding mechanism.

Lastly, in railing against globalization and the loss of American industries, Trump is cutting off America’s traditional allies and trading partners in Europe, Canada and Mexico who account for 54% of all US trade flows in manufactured goods. Cutting them off has only led these countries to look for other alternatives, especially China and India. All of this is not helping the US or its trade deficit. The American manufacturers (except for sectoral beneficiaries in steel, aluminum and auto industries), workers and consumers are paying the price for Trump’s economic idiosyncrasies. As Roach notes, the Court stayed away from the economic considerations, but by declaring Trump’s IEEPA tariffs unconstitutional, the Court has sent an important message to the American people and the rest of the world that “US policies may not be personalized by the whims of a vindictive and uninformed wannabe autocrat.”

by Rajan Philips

Features

The Victor Melder odyssey: from engine driver CGR to Melbourne library founder

He celebrated his 90th birthday recently, never returned to his homeland because he’s a bad traveler

(Continued from last week)

THE GARRAT LOCOS, were monstrous machines that were able to haul trains on the incline, that normally two locos did. Whilst a normal loco hauled five carriages on its own, a Garrat loco could haul nine. When passenger traffic warranted it and trains had over nine carriages or had a large number of freight wagons, then a Garret loco hauled the train assisted by a loco from behind.

When a train was worked by two normal locos (one pulling, the other pushing) and they reached the summit level at Pattipola (in either direction), the loco pushing (piloting) would travel around to the front the train and be coupled in front of the loco already in front and the two locos took the train down the incline. With a Garraat loco this could not be done as the bridges could not take the combined weight. The pilot loco therefore ran down single, following THE TRAIN.

My father was stationed at Nawalapitiya as a senior driver at the time, and it wasn’t a picnic working with him. He believed in the practical side of things and always had the apprentices carrying out some extra duties or the other to acquaint themselves with the loco. I had more than my fair share.

After the four months upcountry, we were back at Dematagoda on the K. V. steam locos. From the sublime to the ridiculous, I would say after the Garret locos upcountry. Here the work was much easier and at a slower pace, as the trains did not run at speed like their mainline counterparts. The last two months of the third year saw us on the two types of diesel locos on the K.V. line, the Hunslett and Krupp diesels, which worked the passenger trains. For once this was a ‘cushy, sit-down’ job, doing nothing exciting, but keeping a sharp lookout and exchanging tablets on the run. The third year had come to an end and ‘the light at the end of tunnel was getting closer’.

The fourth year saw us all at the Diesel loco shed at Maradana, which was cheek by jowl with the Maradana railway station. The first three months we worked with the diesel mechanical fitters and the following three months with the electrical fitters. Heavy emphasis was placed on a working knowledge of the electrical circuits of the different diesel locos in service, to ensure the drivers were able to attend to electrical faults en-route and bring the train home. This was again a period of lectures and demonstrations

We also spent three months at the Ratmalana workshops, where the diesels were stripped down to the core and refitted after major repairs, to ensure we had a look at what went on inside the many closed and sealed working parts. This was again a 7.00am to 4.00pm day job. Back again at the Diesel shed, Maradana, saw us riding as assistants for the next three months on all the diesel locos in service – The Brush Bragnal (M1), General Electrical (M2), Hunslett locos (G2) and Diesel Rail Cars.

After the final written test on Diesel locos, we began our fifth and final year, which was that of shunting engine driver. The first six months were spent at Maligawatte Yard on steam shunting locos and the next three months shunting drivers on the diesel shunting locos at Colombo goods yard. The final three months were spent as assistants on the M1 and M2 locos working all the fast passenger and mail trains.

I was finally appointed Engine Driver Class III on July 6, 1962, as mentioned earlier I lost eight months of my apprenticeship due to being ill and had to make up the time. This appointment was on three years’ probation, on the initial salary of the scale Rs 1,680 – 72 – Rs 2,184, per annum.

Little did the general traveling public realize that they had well trained and qualified engine drivers working their trains to time Victor was stationed in Galle until December 1967, when he resigned from the railway to migrate to Melbourne, Australia to join the rest of his family. He was the last of 11 siblings to leave Ceylon. Their two elder children were born in Galle. Victor and Esther had three more children in Australia. The children, three boys and two girls) were brought up with love and devotion. They have seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren. They meet often as a family.

He worked for the Victorian State Public Service and retired in 1993 after 25 years’ service. At the time of retirement, he worked for the Ministry for Conservation & Environment. He held the position of Project Officer in charge of the Ministry’s Procedural Documents.

He worked part-time for the Victorian Electoral Office and the Australian Electoral Office, covering State and Federal Elections, from 1972 to 2010. From 1972 to 1982 and was a Clerical Officer and then in 1983 was appointed Officer-in-Charge, Lychfield Avenue Polling Booth, Jacana which is my (the writer’s) electorate.

As part of serving the community Victor participated in a number of ways, quite often unremunerated. He worked part-time for the Department of Census & Statistics, and worked as a Census Collector for the Census of 1972, 1976, 1980 and then Group Leader of 16 Collectors in his area for the 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008 and 2012.

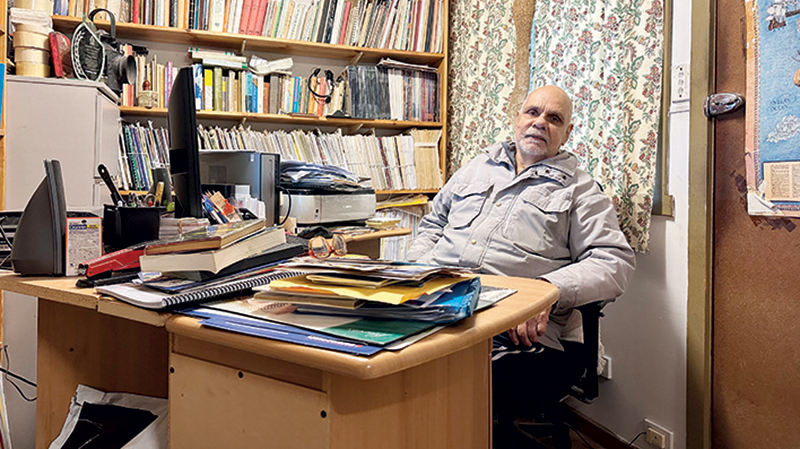

In 1970, Victor began this library, now known as the ‘Victor Melder Sri Lanka Library’, for the purpose of making Sri Lanka better known in Australia. On looking back he has this to say: “Forty-five years later, I can say that it is serving its purpose. In 1993 President Ranasinghe Premadasa of Sri Lanka bestowed on me a national honor – ‘Sri Lanka Ranjana’ for my then 25 years’ service to Sri Lanka in Australia. I feel very privileged to be honored by my motherland, which I feel is the highest accolade one can ever get.”

There were many more accolades over the years:

15.10. 2004, Serendib News, 2004 Business and Community Award.

4.2.2008, Award for Services to the SL Community by The Consulate of Sri Lanka in Victoria (by R. Arambewela)

2024 – SL Consul General’s Award

In 2025 , Victor was one of the ten outstanding Sri Lankans in Australia at the Lankan Fest.

An annual Victor Melder Appreciation award was established to honour an outstanding member by the SriLankan Consulate.

The following appreciation by the late Gamini Dissanayake is very appropriate.

Comment by the late Minister Gamini Dissanayake, in the comment book of the VMSL library.

A man is attached to many things. Attachments though leading to sorrow in the end

are the living reality of life. Amongst these many attachments, the most noble are the attachments to one’s family and to one’s country. You have left Sri Lanka long ago but “she” is within you yet and every nerve and sinew of your body, mind and soul seem to belong there. In your love for the country of your birth you seem to have no racial or religious connotations – you simply love “HER” – the pure, clear, simple, abstract and glowing Sri Lanka of our imagination and vision. You are an example of what all Sri Lankan’s should be. May you live long with your vision and may Sri Lanka evolve to deserve sons like you.

With my best Wishes.

Gamini Dissanayake, Minister from Sri Lanka.

15 February 1987.

The Victor Melder Lecture

The Monash council established the Victor Melder Lecture which is presented every February. It is now an annual event looked forward to by Melbournians. A guest lecturer is carefully chosen each year for this special event.

Victor and his library has featured on many publications such as the Sunday Times in 2008 and LMD International in 2026.

“Although having been a railway man, I am a poor traveler and get travel sickness, hence I have not travelled much. I have never been back to Sri Lanka, never travelled in Australia, not even to Geelong. I am happiest doing what I like best, either at Church or in this library. My younger daughter has finally given up after months of trying to coax, cajole and coerce me into a trip to Sri Lanka to celebrate this (90th) birthday.

I am most fortunate that over the years I have made good friends, some from my school days. It is also a great privilege to grow old in the company of friends — like-minded individuals who have spent their childhood and youth in the same environment as oneself and shared similar life experiences.”

Victor’s love of books started from childhood. Since his young years he has been interested in reading. At St Mary’s College, Nawalapitiya, the library had over 300 books on Greek and Roman history and mythology and he read every one of them.

He read the newspapers daily, which his parents subscribed to, including the ‘Readers Digest’.His mother was an avid fan of Crossword Puzzles and encouraged all the children to follow her, a trait which he continues to this day.

At his workplace in Melbourne, Victor encountered many who asked questions about Ceylon. Often, he could not find an answer to these queries. This was long before the internet existed. He then started getting books on Ceylon/SriLanka and reading them. Very soon his collection expanded and he thought of the Vicor Melder SriLanka Library as source of reference. It is now a vast collection of over 7,000 books, magazines and periodicals.

Another driver of his service to fellow men is his deep Catholic faith in which he follows the footsteps of the Master.

Victor was baptized at St Anthony’s Cathedral, Kandy by Fr Galassi, OSB. Since the age of 10 he have been involved with Church activities both in Sri Lanka and Australia. He remains a devout Catholic and this underlies his spirit of service to fellowmen.

He began as an Altar Server at St Mary’s Church, Nawalapitiya, and continued even in his adult life. In Australia, Esther and Victor have been Parishioners at St Dominic’s Church, Broadmeadows, since 1970.He started as an Adult Server and have been an Altar Server Trainer, Reader and Special Minister He was a member of the ‘Counting Team’ for monies collected at Sunday Masses, for 35 years.

He has actively retired from this work since 2010, but is still ‘on call’, to help when required. To add in his own words

“My Catholic faith has always been important to me, and I can never imagine my having spent a day away from God. Faith is all that matters to Esther too. We attend daily Mass and busy ourselves with many activities in our Parish Church.

For nearly 25 years, we have also been members of a religious order ‘The Community of the Sons & Daughters of God’, it is contemplative and monastic in nature, we are veritable monks in the world. We do no good works, other than show Christ to the world, by our actions. Both Esther and I, after much prayer and discernment have become more deeply involved, taking vows of poverty, obedience and chastity, within the Community. Our spirituality gives us much peace, solace and comfort.”

“This is not my CV for beatification and canonization. My faith is in fact an antidote for overcoming evil, I too struggle like everyone else. I have to exorcise the demons within me by myself. I am a perfect candidate for “being a street angel and home devil” by my constant impatience, lack of tolerance and wanting instant perfection from everyone. “

The above exemplifies the humility of the man who admits to his foibles.

More than 25 years ago The Ceylon Society of Australia was formed in Sydney by a group of Ceylon lovers led by Hugh Karunanayake. Very soon the Melbourne chapter of the organization was formed, and Victor was a crucial part of this. At every Talk, Victor displayed books relevant to the topic. For many years he continued to do so carrying a big box of books and driving a fair distance to the meeting place. Eventually when he could no longer drive his car, he made certain that the books reached the venue through his close friend, Hemal Gurusinghe.

He also was the guest speaker at one of the meetings and he regaled the audience with railway stories.

Victor has dedicated his life on this mission, and we can be proud of his achievements. His vision is to find a permanent home for his library where future generations can use it and continue the service that he commenced. The plea is to get like-minded individuals in the quest to find a suitable and permanent home for the Victor Melder Srilankan Library.

by Dr. Srilal Fernando

Features

Sri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

Sri Lanka is set to make scientific history by hosting the world’s first global conference dedicated entirely to snake research, conservation and public health, with the World Congress on Snakes (WCS) 2026 scheduled to take place from October 1–4 at The Grand Kandyan Hotel in Kandy World Congress on Snakes.

The congress marks a major milestone not only for Sri Lanka’s biodiversity research community but also for global collaboration in herpetology, conservation science and snakebite management.

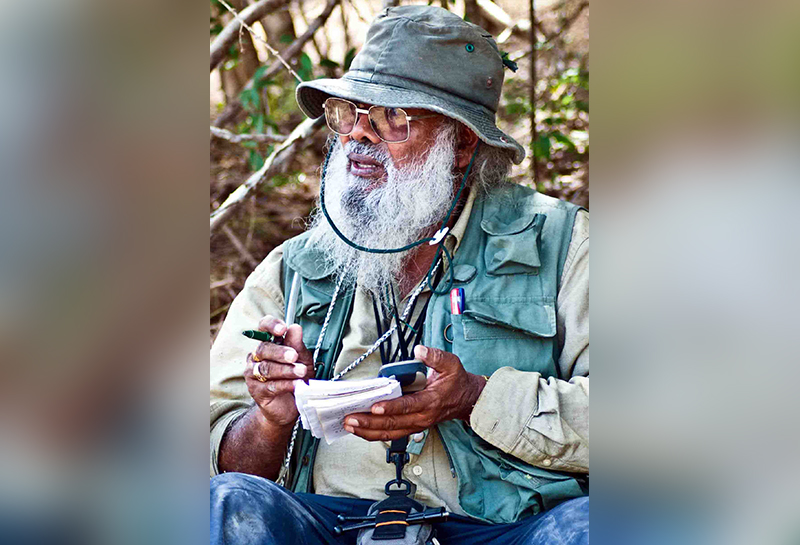

Congress Chairperson Dr. Anslem de Silva described the event as “a long-overdue global scientific platform that recognises the ecological, medical and cultural importance of snakes.”

“This will be the first international congress fully devoted to snakes — from their evolution and taxonomy to venom research and snakebite epidemiology,” Dr. de Silva said. “Sri Lanka, with its exceptional biodiversity and deep ecological relationship with snakes, is a fitting host for such a historic gathering.”

Global Scientific Collaboration

The congress has been established through an international scientific partnership, bringing together leading experts from Sri Lanka, India and Australia. It is expected to attract herpetologists, wildlife conservationists, toxinologists, veterinarians, genomic researchers, policymakers and environmental organisations from around the world.

The International Scientific Committee includes globally respected experts such as Prof. Aaron Bauer, Prof. Rick Shine, Prof. Indraneil Das and several other authorities in reptile research and conservation biology.

Dr. de Silva emphasised that the congress is designed to bridge biodiversity science, medicine and society.

“Our aim is not merely to present academic findings. We want to translate science into practical conservation action, improved public health strategies and informed policy decisions,” he explained.

Addressing a Neglected Public Health Crisis

A key pillar of the congress will be snakebite envenoming — widely recognised as a neglected tropical health problem affecting rural communities across Asia, Africa and Latin America.

“Snakebite is not just a medical issue; it is a socio-economic issue that disproportionately impacts farming communities,” Dr. de Silva noted. “By bringing clinicians, toxinologists and conservation scientists together, we can strengthen prevention strategies, improve treatment protocols and promote community education.”

Scientific sessions will explore venom biochemistry, clinical toxinology, antivenom sustainability and advances in genomic research, alongside broader themes such as ecological behaviour, species classification, conservation biology and environmental governance.

Dr. de Silva stressed that fear-driven persecution of snakes, habitat destruction and illegal wildlife trade continue to threaten snake populations globally.

“Snakes play an essential ecological role, particularly in controlling rodent populations and maintaining agricultural balance,” he said. “Conservation and public safety are not opposing goals — they are interconnected. Scientific understanding is the foundation for coexistence.”

The congress will also examine cultural perceptions of snakes, veterinary care, captive management, digital monitoring technologies and integrated conservation approaches linking biodiversity protection with human wellbeing.

Strategic Importance for Sri Lanka

Hosting the global event in the historic city of Kandy — a UNESCO World Heritage site — is expected to significantly enhance Sri Lanka’s standing as a hub for scientific and environmental collaboration.

Dr. de Silva pointed out that the benefits extend beyond the four-day meeting.

“This congress will open doors for Sri Lankan researchers and students to access world-class expertise, training and international partnerships,” he said. “It will strengthen our national research capacity in biodiversity and environmental health.”

He added that the event would also generate economic activity and position Sri Lanka as a destination for high-level scientific conferences, expanding the country’s international image beyond traditional tourism promotion.

The congress has received support from major international conservation bodies including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Save the Snakes, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo and the Amphibian and Reptile Research Organization of Sri Lanka (ARROS).

As preparations gather momentum, Dr. de Silva expressed optimism that the World Congress on Snakes 2026 would leave a lasting legacy.

“This is more than a conference,” he said. “It is the beginning of a global movement to promote science-based conservation, improve snakebite management and inspire the next generation of researchers. Sri Lanka is proud to lead that conversation.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoIndia, South Africa meet in the final before the final

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoProtection of Occupants Bill: Good, Bad and Ugly

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPrime Minister Attends the 40th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Nippon Educational and Cultural Centre

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHuawei unveils Top 10 Smart PV & ESS Trends for 2026

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCoal ash surge at N’cholai power plant raises fresh environmental concerns