Features

Revisiting Humanism in Education:Insights from Tagore

By Panduka Karunanayake

Professor in the Department of Clinical Medicine and former Director, Staff Development Centre, University of Colombo

(The 34th J.E. Jayasuriya Memorial Lecture14 February 2025 SLFI Auditorium, Colombo)

Professor J.E. Jayasuriya is remembered today for his work in so many diverse aspects of the field of education. Indeed, one can be forgiven for wondering whether this is just one person or a combination of several. These aspects include his excellence as a teacher and a writer of textbooks on Mathematics; a renowned school principal, handpicked by Dr C.W.W. Kannangara to establish the first Central College; an able administrator; a Professor of Education in the University of Ceylon and a leading academic; a pioneer in the fields of educational psychology, population education and even my own area of medical education; a policymaker, analyst and commentator at both national and international levels; an advocate and political activist; an internationally recognised expert and author; and last but not least, a great teacher and much-loved mentor. My own debt to his work would be patently obvious to anyone who reads my book Ruptures in Sri Lanka’s Education, in which I have relied heavily on his insightful analyses. It is no surprise, therefore, that this memorial lecture had been delivered in the past by some of the most eminent women and men of intellect produced by our country, not only from the field of education but even other fields. I am truly humbled when I think of the stature of this great intellectual or read the list of those eminent past speakers. I will strive to do justice to the expectations placed on me by the J.E. Jayasuriya Memorial Foundation when they invited me to join that list of names, and I thank the President and Management Council of the Foundation. Following in Professor Jayasuriya’s path, in this lecture I, too, will deal with education as a social institution and look at it through a wide-angle lens.

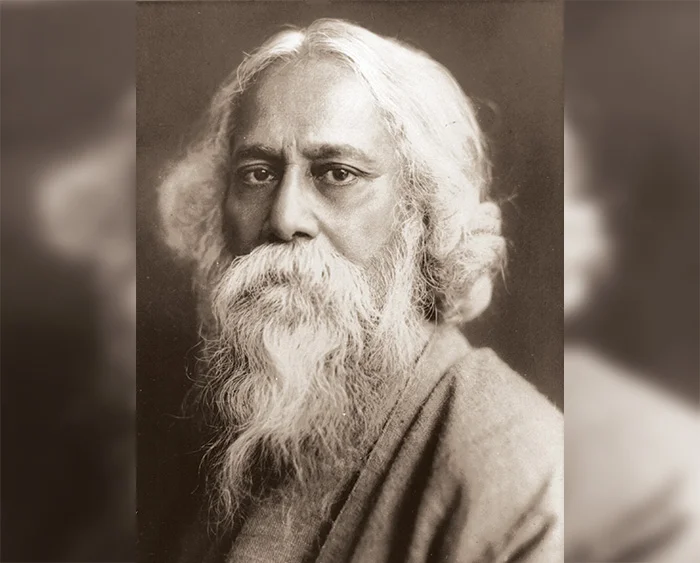

Ladies and Gentlemen: For some time now, I have been impressed by the education-related work of the great Indian intellectual Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). (His actual name in Bengali is Robindronat Thakur: the name Rabindranath Tagore is an anglicisation, much better known across the world than the Bengali original.) Tagore was, of course, a very famous person: the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize; a well-known poet, lyricist, musician, dramatist, novelist and painter; a polymath; an inspiring writer and public speaker; a social reformer; a philosopher; and one of the most widely travelled Indians of his generation and, unsurprisingly, an internationalist. In fact, his work on education – while an amazing labour of love – might be thought of as a lesser known part in his fame. In this lecture, I wish to delve specifically on his work on education.

One could point out that he carried out his iconoclastic experiments in education a century ago, and that the educational institutions that he created back then exist now only in name. Their original nature has changed with the rigors of time. So am I here trying to recreate a world one hundred years past and propagate nostalgia? If you bear with me, I trust you will find that my reasons are better than that.

The reason why I was so impressed with his work is the significant currency of his ideas to the contemporary world. Now this will immediately seem like a contradiction. If the ideas are still current, why did the institutions that were based on those ideas have to change with time?

I would explain these two contradictory positions by saying that his ideas were actually prescient – they weren’t sustained, because they were ahead of their time. Besides, although he correctly identified problems and designed effective solutions, the problems were not fully solved by them – because of asymmetrical power relations and lack of funding. Today, we see the same problems throughout the globe – in all their enormity, reach and complexity. They engulf us and in a way blind us, because we have been trained to think that the reasons underlying them are ‘natural givens’. And by a quirk of fate, the solutions are now hidden in the sands of time.

Let me offer a quick illustration of this. We can clearly identify elements of humanistic education in Tagore’s ideas, even though humanistic education itself was recognised only some decades after his death and still hasn’t permeated education widely.

In this lecture, I would invite you to retrace my own steps into his educational philosophy. I, too, began with the belief that his ideas were hopelessly out of tune with our times. That was because I had been trained to see the world of education in a certain way, and from that position Tagore’s ideas seemed alien. I am reminded of something that Marcel Proust wrote: “The real journey of discovery lies not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” But as we all know, letting go of existing perceptions and forming entirely new ones is probably the hardest thing for the human mind to do. And yet, as any good educator would tell you, learning to form new perceptions is the very essence of education.

Current education landscape and its discontents

Let me start with a proposition. Education in today’s world needs a fundamental reposturing – not because it is doing its job badly but because it is doing the wrong job. Everywhere we can see educational institutions doing a great job, but our society is no better for it. This state of affairs hasn’t risen suddenly or recently; rather, it has been emerging slowly and developing over a century or so.

Let us examine the last one hundred years or so. During this time, throughout the world, democratisation has given expanding access to education, decolonisation has helped to switch the medium of instruction from colonising languages to the mother tongue, expanding industries and middle class populations have led to increasing massification of university education, and the human capital theory has led to increasing investment and growth in all levels of education. Can anyone in education think of a better century?

But during this same period, what has education given society? Chemists invented the weapons of the First World War. Physicists invented the weapons of the Second World War. Biologists bequeathed us biological weapons. Medicine became more successful and less trustworthy. Economics created economic hit men and cross-border practices that made markets volatile and national economies vulnerable. The law reduced community rights and increased patent rights. Mass communications, which could not give populations any democratic skills, could nevertheless give them insatiable consumerism. Social scientists have not explained the underlying reasons, much less solve them, but continue to create faultlines in societies and fragment them. The humanities have failed to bring the human family closer. And the biggest invention that technology has given us thus far is climate change.

It would not be enough to merely put the blame for all this on a few demagogues or dictators – throughout this period, populations had at least acquiesced with them and had often strengthened them. The purpose of education should have been to give the masses the skill to avoid these traps, but instead, the masses have been compliant while the experts have been selling their souls. This is why I said that education – assuming it was doing its job well – has been doing the wrong job.

The question of why education went to work for ‘the wrong boss’ has intrigued me for some time now, all the more because I know that during this whole period, policymakers and educationists have mostly been genuine in their intentions. My earliest clues came from two writers from the 1960s and 1970s. The first was the iconoclastic social critic Ivan Illich (1970) who published the book Deschooling Society. The second was a relatively unknown American education administrator, Grant Venn (1965, 1971).

Venn pointed out that throughout the twentieth century, the role that was required of education in society was undergoing a gradual change, although its response was not forthcoming. The general organisational structure of education everywhere was one that had been inherited from the time of the Industrial Revolution, but changing times were demanding a new structure. But educationists everywhere were not perceptive to it. They merely kept the old structure and tried to tinker with it.

In the old days, the majority of schoolchildren were destined to end up in farms, mines or manufactories, and they only needed an education in the 3 R’s and some basic disciplines such as punctuality. Only a few had to be selected and groomed for higher office. Learning how to live well, on the other hand, was acquired quite easily outside of school. The school itself played a relatively small role in people’s lives, except for the select few, and nobody would have equated education to school-going, because much of education happenned outside school. Our organisational structure was one that was created for this era.

But all this changed after the increasing domination of scientific technology in society. Thereafter, more schoolchildren had to be educated to a higher level – as tasks transformed from physical ones to cognitive ones, ‘work’ transformed into ‘jobs’, and the preparation needed for a life transformed from apprenticeship to prolonged schooling. Schools became a pervasive presence in people’s lives and tied them to their destinies, both individually and at the national level. Gradually, education became equated to school-going – learning how to live well, which had been learnt outside school, became sidelined, ignored and eventually lost.

As Venn observed:

[C]hanges now confronting us must be thought about in terms of certain new relationships that have developed between man, education, and society. Essentially, for the first time in man’s history, education is the link between an individual and society; and for the

first time this is true for every individual. Education, instead of a selection agency, must become an including agency.

When he suggested here that education must change from a selection agency to an including agency, he was referring to inclusion in the world of work and community, rather than merely inclusion in the school. In other words, he wasn’t talking about access to education – he was worried about what would happen to school-leavers when they go to live in the world outside.

If we look back at how education did respond, we would see that it has been preoccupied with strengthening the link between school and work. Let’s take Sri Lanka. In the 1970s we had pre-vocational studies. In the 1980s we had life skills. In the 1990s we had soft skills. In the 2000s we had twenty-first century skills. Nowadays we have industry-based capstone projects and entrustable professional activities. By and large, these were not our own inventions – they were simply the global responses replicated locally. But even these had no chance of success, because while education could prepare school-leavers for jobs, the economy still had to create those jobs. Without that, all one could have is what Ronald Dore (1976) forewarned us: qualification inflation and qualification escalation. In the 1960s the human capital theory suggested that education could serve as a springboard for economic development, and there were, indeed, some early successes, such as with Japan and South Korea. But more recently, that theory, too, has run into controversies and failure.

The failure to adapt to these changing circumstances manifested as what we see today in its fully developed form. We have over-indulged ourselves in designing education to chase after employment, and compromised education’s role in preparing students to be citizens in the community. This is not to say that education should not have played a role in economic development or preparing its students for the world of work. It is to point out the loss of balance in achieving these two goals: economic development on the one hand and human flourishing on the other hand.

But while education may have lost sight of the second goal, it also didn’t do very well promoting the first goal. Even here, it has lost its way.

After the Cold War ended in the 1990s a bipolar world was replaced by a unipolar world, with ‘all roads leading to Washington’. When that happened, a more balanced use of technology – what used to be known in the 1970s as ‘appropriate technology’ – was replaced by the use of often highly expensive and inappropriate technology that came tied to funding. This was because the global economy was capitulating to the major industries and multinational corporations and conglomerates, which were initially situated in the West but are now situated in other countries, too. We can conceptualise these as the ‘core’ in the ‘core-periphery relationship’ in global financing, knowledge production and commoditisation.

The reason why education lost its way is because that, too, became merged with – and disappeared into – this core-periphery relationship. Education ceased to serve local communities or support appropriate technology, and instead began serving the interests of big industries and promoting inappropriate technological behemoths. In the past, a well-educated person was one who served one’s community well – today the well-educated person is one who works for a successful global industrial giant.

One of the interesting changes in education that was promoted by the World Bank in the 1990s was the concept of the ‘three E’s’ of education: effectiveness, equity and efficiency. They were meant to help align educational systems to national goals. But they were overly quantitative, promoting measurable outcomes and ignoring the unmeasurable ones. What they succeeded in doing is replacing the broad goals of education with immediately measurable outcomes. Thus, quality was pushed aside in favour of effectiveness, and value-for-money in favour of efficiency. Insidiously, we also began chasing after the measurable parameters that served the industries in the core countries. Today, we judge ourselves by their indices, such as webometrics, accreditations and citations.

Even before these quantitative indices emerged, Venn asked some insightful questions about ‘quality’. Can quality be measured based on how well the institution serves those most in need of education rather than only those who are lucky, or defined in terms of how well individual differences and unique talents are developed rather than how well students become like all others, or in terms of one’s behaviour and contributions after one leaves school rather than on what one does while in school? Can accreditation be based on how well the school succeeds in its own goals rather than those of other schools? Can status for an educational institution be gained by how well it meets unfilled needs of society rather than how much it is like recognised institutions? We ought to have focused on these tasks; but instead, we have lost these unmeasurable attributes in our rush to comply with measurable parameters.

But it is not merely that this approach has robbed society of important attributes that were unmeasurable. Arguably, even those who were ‘successfully educated’ lack a wholesome education. This had been noted even before the 1990s, as when Aldous Huxley wrote in his book Psychedelics:

Literary or scientific, liberal or specialist, all our education…fails to accomplish what it is supposed to do. Instead of transforming children into fully developed adults, it turns out students of the natural sciences who are completely unaware of Nature as the primary fact of experience, it inflicts upon the world students of the Humanities who know nothing of humanity, their own or anyone else’s.

To use a phrase from his book, we have mistaken the menu for the meal!

So what kind of different organisational structure would help us achieve this balance? Let me quote Illich, as he hints the answer:

Everyone learns how to live outside school. We learn to speak, to think, to love, to feel, to play, to curse, to politick and to work without interference from a teacher… Increasingly, educational research demonstrates that children learn most of what teachers pretend to teach them from peer groups, from comics, from chance observations,…”

– and to this, today I could add ‘from social media and the Internet’.

In other words, although the education-industry link is important, we need to realise that education itself is a lot more than this role. In order to capture the other important goals of education, we must broad-base it. Education is not something that happens only in the syllabus; it happens outside it, too. It is not something that is destined to enter only the workplace; it enters our private lives and community life, too. In fact, its true value lies therein. We need to rediscover this balance – this broader concept of education.

It is when we begin to see the true role of education in this way that we can begin to see sense in Tagore’s ideas. So now, it is time to turn to him.

Features

Meet the women protecting India’s snow leopards

In one of India’s coldest and most remote regions, a group of women have taken on an unlikely role: protecting one of Asia’s most elusive predators, the snow leopard.

Snow leopards are found in just 12 countries across Central and South Asia. India is home to one of the world’s largest populations, with a nationwide survey in 2023 – the first comprehensive count ever carried out in the country – estimating more than 700 animals, .

One of the places they roam is around Kibber village in Himachal Pradesh state’s Spiti Valley, a stark, high-altitude cold desert along the Himalayan belt. Here, snow leopards are often called the “ghosts of the mountains”, slipping silently across rocky slopes and rarely revealing themselves.

For generations, the animals were seen largely as a threat, for attacking livestock. But attitudes in Kibber and neighbouring villages are beginning to shift, as people increasingly recognise the snow leopard’s role as a top predator in the food chain and its importance in maintaining the region’s fragile mountain ecosystem.

Nearly a dozen local women are now working alongside the Himachal Pradesh forest department and conservationists to track and protect the species, playing a growing role in conservation efforts.

Locally, the snow leopard is known as Shen and the women call their group “Shenmo”. Trained to install and monitor camera traps, they handle devices fitted with unique IDs and memory cards that automatically photograph snow leopards as they pass.

“Earlier, men used to go and install the cameras and we kept wondering why couldn’t we do it too,” says Lobzang Yangchen, a local coordinator working with a small group supported by the non-profit Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) in collaboration with the forest department.

Yangchen was among the women who helped collect data for Himachal Pradesh’s snow leopard survey in 2024, which found that the state was home to 83 snow leopards – up from 51 in 2021.

The survey documented snow leopards and 43 other species using camera traps spread across an area of nearly 26,000sq km (10,000sq miles). Individual leopards were identified by the unique rosette patterns on their fur, a standard technique used for spotted big cats. The findings are now feeding into wider conservation and habitat-management plans.

“Their contribution was critical to identifying individual animals,” says Goldy Chhabra, deputy conservator of forests with the Spiti Wildlife Division.

Collecting the data is demanding work. Most of it takes place in winter, when heavy snowfall pushes snow leopards and their prey to lower altitudes, making their routes easier to track.

On survey days, the women wake up early, finish household chores and gather at a base camp before travelling by vehicle as far as the terrain allows. From there, they trek several kilometres to reach camera sites, often at altitudes above 14,000ft (4,300m), where the thin air makes even simple movement exhausting.

The BBC accompanied the group on one such trek in December. After hours of walking in biting cold, the women suddenly stopped on a narrow trail.

Yangchen points to pugmarks in the dust: “This shows the snow leopard has been here recently. These pugmarks are fresh.”

Along with pugmarks, the team looks for other signs, including scrapes and scent‑marking spots, before carefully fixing a camera to a rock along the trail.

One woman then carries out a “walk test”, crawling along the path to check whether the camera’s height and angle will capture a clear image.

The group then moves on to older sites, retrieving memory cards and replacing batteries installed weeks earlier.

By mid-afternoon, they return to camp to log and analyse the images using specialised software – tools many had never encountered before.

“I studied only until grade five,” says Chhering Lanzom. “At first, I was scared to use the computer. But slowly, we learned how to use the keyboard and mouse.”

The women joined the camera-trapping programme in 2023. Initially, conservation was not their motivation. But winters in the Spiti Valley are long and quiet, with little agricultural work to fall back on.

“At first, this work on snow leopards didn’t interest us,” Lobzang says. “We joined because we were curious and we could earn a small income.”

The women earn between 500 ($5.46; £4) and 700 rupees a day.

But beyond the money, the work has helped transform how the community views the animal.

“Earlier, we thought the snow leopard was our enemy,” says Dolma Zangmo, a local resident. “Now we think their conservation is important.”

Alongside survey work, the women help villagers access government insurance schemes for their livestock and promote the use of predator‑proof corrals – stone or mesh enclosures that protect animals at night.

Their efforts come at a time of growing recognition for the region. Spiti Valley has recently been included in the Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve, a Unesco-recognised network aimed at conserving fragile ecosystems while supporting local livelihoods.

As climate change reshapes the fragile trans-Himalayan landscape, conservationists say such community participation will be crucial to safeguarding species like the snow leopard.

“Once communities are involved, conservation becomes more sustainable,” says Deepshikha Sharma, programme manager with NCF’s High Altitudes initiative.

“These women are not just assisting, they are becoming practitioners of wildlife conservation and monitoring,” she adds.

As for the women, their work makes them feel closer to their home, the village and the mountains that raised them, they say.

“We were born here, this is all we know,” Lobzang says. “Sometimes we feel afraid because these snow leopards are after all predatory animals, but this is where we belong.”

[BBC]

Features

Freedom for giants: What Udawalawe really tells about human–elephant conflict

If elephants are truly to be given “freedom” in Udawalawe, the solution is not simply to open gates or redraw park boundaries. The map itself tells the real story — a story of shrinking habitats, broken corridors, and more than a decade of silent but relentless ecological destruction.

“Look at Udawalawe today and compare it with satellite maps from ten years ago,” says Sameera Weerathunga, one of Sri Lanka’s most consistent and vocal elephant conservation activists. “You don’t need complicated science. You can literally see what we have done to them.”

What we commonly describe as the human–elephant conflict (HEC) is, in reality, a land-use conflict driven by development policies that ignore ecological realities. Elephants are not invading villages; villages, farms, highways and megaprojects have steadily invaded elephant landscapes.

Udawalawe: From Landscape to Island

Udawalawe National Park was once part of a vast ecological network connecting the southern dry zone to the central highlands and eastern forests. Elephants moved freely between Udawalawe, Lunugamvehera, Bundala, Gal Oya and even parts of the Walawe river basin, following seasonal water and food availability.

Today, Udawalawe appears on the map as a shrinking green island surrounded by human settlements, monoculture plantations, reservoirs, electric fences and asphalt.

“For elephants, Udawalawe is like a prison surrounded by invisible walls,” Sameera explains. “We expect animals that evolved to roam hundreds of square nationakilometres to survive inside a box created by humans.”

Elephants are ecosystem engineers. They shape forests by dispersing seeds, opening pathways, and regulating vegetation. Their survival depends on movement — not containment. But in Udawalawa, movement is precisely what has been taken away.

Over the past decade, ancient elephant corridors have been blocked or erased by:

Irrigation and agricultural expansion

Tourism resorts and safari infrastructure

New roads, highways and power lines

Human settlements inside former forest reserves

“The destruction didn’t happen overnight,” Sameera says. “It happened project by project, fence by fence, without anyone looking at the cumulative impact.”

The Illusion of Protection

Sri Lanka prides itself on its protected area network. Yet most national parks function as ecological islands rather than connected systems.

“We think declaring land as a ‘national park’ is enough,” Sameera argues. “But protection without connectivity is just slow extinction.”

Udawalawe currently holds far more elephants than it can sustainably support. The result is habitat degradation inside the park, increased competition for resources, and escalating conflict along the boundaries.

“When elephants cannot move naturally, they turn to crops, tanks and villages,” Sameera says. “And then we blame the elephant for being a problem.”

The Other Side of the Map: Wanni and Hambantota

Sameera often points to the irony visible on the very same map. While elephants are squeezed into overcrowded parks in the south, large landscapes remain in the Wanni, parts of Hambantota and the eastern dry zone where elephant density is naturally lower and ecological space still exists.

“We keep talking about Udawalawe as if it’s the only place elephants exist,” he says. “But the real question is why we are not restoring and reconnecting landscapes elsewhere.”

The Hambantota MER (Managed Elephant Reserve), for instance, was originally designed as a landscape-level solution. The idea was not to trap elephants inside fences, but to manage land use so that people and elephants could coexist through zoning, seasonal access, and corridor protection.

“But what happened?” Sameera asks. “Instead of managing land, we managed elephants. We translocated them, fenced them, chased them, tranquilised them. And the conflict only got worse.”

The Failure of Translocation

For decades, Sri Lanka relied heavily on elephant translocation as a conflict management tool. Hundreds of elephants were captured from conflict zones and released into national parks like Udawalawa, Yala and Wilpattu.

The logic was simple: remove the elephant, remove the problem.

The reality was tragic.

“Most translocated elephants try to return home,” Sameera explains. “They walk hundreds of kilometres, crossing highways, railway lines and villages. Many die from exhaustion, accidents or gunshots. Others become even more aggressive.”

Scientific studies now confirm what conservationists warned from the beginning: translocation increases stress, mortality, and conflict. Displaced elephants often lose social structures, familiar landscapes, and access to traditional water sources.

“You cannot solve a spatial problem with a transport solution,” Sameera says bluntly.

In many cases, the same elephant is captured and moved multiple times — a process that only deepens trauma and behavioural change.

Freedom Is Not About Removing Fences

The popular slogan “give elephants freedom” has become emotionally powerful but scientifically misleading. Elephants do not need symbolic freedom; they need functional landscapes.

Real solutions lie in:

Restoring elephant corridors

Preventing development in key migratory routes

Creating buffer zones with elephant-friendly crops

Community-based land-use planning

Landscape-level conservation instead of park-based thinking

“We must stop treating national parks like wildlife prisons and villages like war zones,” Sameera insists. “The real battlefield is land policy.”

Electric fences, for instance, are often promoted as a solution. But fences merely shift conflict from one village to another.

“A fence does not create peace,” Sameera says. “It just moves the problem down the line.”

A Crisis Created by Humans

Sri Lanka loses more than 400 elephants and nearly 100 humans every year due to HEC — one of the highest rates globally.

Yet Sameera refuses to call it a wildlife problem.

“This is a human-created crisis,” he says. “Elephants are only responding to what we’ve done to their world.”

From expressways cutting through forests to solar farms replacing scrublands, development continues without ecological memory or long-term planning.

“We plan five-year political cycles,” Sameera notes. “Elephants plan in centuries.”

The tragedy is not just ecological. It is moral.

“We are destroying a species that is central to our culture, religion, tourism and identity,” Sameera says. “And then we act surprised when they fight back.”

The Question We Avoid Asking

If Udawalawe is overcrowded, if Yala is saturated, if Wilpattu is bursting — then the real question is not where to put elephants.

The real question is: Where have we left space for wildness in Sri Lanka?

Sameera believes the future lies not in more fences or more parks, but in reimagining land itself.

“Conservation cannot survive as an island inside a development ocean,” he says. “Either we redesign Sri Lanka to include elephants, or one day we’ll only see them in logos, statues and children’s books.”

And the map will show nothing but empty green patches — places where giants once walked, and humans chose. roads instead.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAll set for Global Synergy Awards 2026 at Waters Edge