Opinion

Revisiting Humanism in Education: Insights from Tagore – II

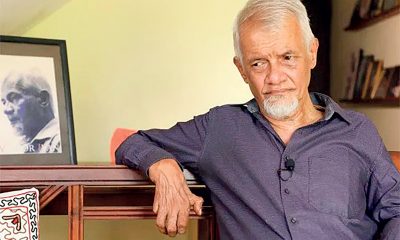

by Panduka Karunanayake

Professor in the Department of Clinical Medicine and former Director, Staff Development Centre,

University of Colombo

The 34th J.E. Jayasuriya Memorial Lecture

14 February 2025

SLFI Auditorium, Colombo

(Continued from 17 Feb.)

Tagore and humanism

Tagore was born to a wealthy Bengali family in British colonial India in the year 1861. This was a time of great social transformation in India, involving political, social, religious and literary movements. In his youth he saw the organisational structure that I described in its formative days, and immediately realised how it is unsuited for anything except the British colonial plans. In particular, he appreciated the strengths of traditional Indian education such as the gurukula, ashrama and tapovana systems, the value of the aesthetic sense to human growth and the role of the environment in our lives. He placed a huge importance on emotions and social values, and decried a materialistic or hedonistic approach to life. Always explaining his ideas through brilliant similes, he said: “The timber merchant may think that flowers and foliage are only frivolous decorations for a tree, but he will know to his cost that if these are eliminated, the timber follows them.”

But he also saw the value of the science and technology that the British were bringing in. He wasn’t a simplistic indigene fighting to chase the British out. He wanted to combine the good of both the old and the new, both India and the world. The best description that we can give of the man is call him a great harmoniser of ideas and an incorrigible optimist.

According to Subhransu Maitra, who is a well-known Indian intellectual who translates Bengali works into English, Tagore’s experimental journey on education lasted approximately fifty years, from the 1890s to the 1940s, and evolved through three phases. In the first phase, roughly from the 1890s to the 1910s, he thought of education as ‘freedom to learn,’ in contradistinction to the kind of straightjacketed rote-learning that British colonial education had introduced to India. He also fought for education in the mother tongue instead of English. This was the time Tagore set up the Brahmacharyashrama, a school for boys in Santiniketan. In the second phase, from the 1910s to the 1930s, he thought of education as ‘freedom from ignorance and want’ and as a powerful tool to emancipate humanity from poverty, superstition and suffering. This was the time when he set up the Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan, his version of a university, as well as Sriniketan, his effort at rural upliftment. And in the third phase, from the 1930s until his death in 1941, which was the time when Visva-Bharati was flourishing, he thought of education as an internationalist, humanist project or ‘freedom from bondage’, in contradistinction to nationalism. I will follow Tagore’s journey in this sequence, and at each stage try to highlight the lessons his educational philosophy gives us today.

But in toto, I feel that the common thread that runs through this journey is his commitment to humanistic education – a term that actually became popular only after his death, following the work of educational psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. So let me start by briefly explaining what humanistic education means.

Humanistic education is the application of the principles of humanism or humanistic philosophy to education. I am sure that many in this audience already know what humanism means, but bear with me when I try to explain it. I want to highlight the fact that humanism is not the same as some concepts with which it is often conflated – such as humanitarianism or humaneness or the humanities. In essence, humanism believes in the primacy of human agency, or the belief that humans are in charge of their own destinies; it is an Enlightenment idea that took agency away from divinity and placed it in the hands of the human being. (But of course, it is also very much part of some ancient philosophies.) But it identifies this agency as a responsibility both to oneself and one’s society, rather than as a libertarian licence. The ideal of humanism is human flourishing – not hedonism, nor any goal in the afterlife.

In humanism, human beings are considered independent, inherently good and capable of positive growth. One might look at these assumptions somewhat cynically – but it is hard to deny these qualities to a newborn child who has arrived on this world in all its innocence. As Tagore once famously said, “Every child comes with the message that God is not yet discouraged of man.”

As Ratna Navaratnam (1958) wrote in New Frontiers in East-West Philosophies of Education:

“Humanism takes as its dominant pattern the progress of the individual from helpless infancy to self-governing maturity…The child is put at the centre of the picture and the educator judges the truth of any theory and the success of any system, by the contribution it makes to the transformation of creative childhood into creative manhood.”

In humanistic education, several features can be identified:

* The student is given a free choice to decide what to study, how and for how long, within reason. As a result, the motivation to learn is intrinsic, rather than extrinsic goals such as exams, grades or certificates.

* The educational experience is left open, exploratory and self-driven. There is little or no emphasis on a curriculum, syllabus or what we today call ‘intended learning outcomes’.

* The setting for learning is safe. What the teacher does is provide the student with the resources to quench curiosity and play a supportive and facilitatory role, as a resource person and guide. There is no coercion, judgement, criticism or corporeal punishment.

* The learning environment focuses on both cognitive and emotional aspects of the learning experience; in other words, both ‘knowing’ and ‘feeling’ are considered valid and important to the learning process.

* And finally, at least a significant portion of the learning time is spent in contact with nature and the environment, rather than inside a classroom.

With that background, let me now turn to the three phases in Tagore’s journey in education.

Phase 1: ‘Freedom to learn’

Tagore was urged to experiment with education because he saw the unsatisfactory nature of schools, which he described as “…educational factories, lifeless, colourless, dissociated from the context of the universe, within bare white walls, staring like eyeballs of the dead…It provided information and knowledge for the intellectual growth and it neglected the aspects of human growth.”

Let me quote Tagore at length:

“The way we understand it, the word school means an education factory or mill of which the schoolmaster is a part. The bell goes off at half past ten and the mill begins to work. As the mill starts, the master also keeps spouting off. The mill closes at four o’clock. The master too, stops spouting and the students return home, their heads stuffed with factory-made lessons. Later, at the time of examinations, these lessons are evaluated and stamped.

“The advantage of factory production is that the products are exactly made to a standard and the products of different factories differ but little from one another. So, it is easy to grade them. But individuals differ a great deal from one another. Even an individual may not be the same from one day to the next.

“Even so, a man cannot get from machines what he gets from another man. A machine produces, it can’t give. It can supply oil, but it can’t light a lamp.”

Tagore’s journey was dedicated to find a suitable alternative to such factory-style education

You can see that he disliked uniformity and intellectual dominance in education, and he preferred freedom to do, experience, feel and learn. This is especially noteworthy today, because educational psychologists have since found the importance of the affective domain for learning: the so-called cognitive-emotional model of learning.

Importantly, the reason he liked a more active style of learning is not merely because it is better for assimilation or long-term memory – as we are accustomed to think today – but because it promoted the growth of individual talents and tastes and imparted a communitarian rather than an individualistic outlook to life.

He also preferred a more idyllic, rural setting to educate children, because he felt that cities and towns rob the students of their bonding with nature, which was necessary for the growing mind to grow freely, wholistically and strongly. This also included creating opportunities for social contact with the rural folk, and trying to help the villagers at least in small ways. So he was especially keen that school and society were welded together. That was his way of teaching two things: first, communication skills, and second, a sense of social service. It would be interesting to compare this to a similar local experiment: Dr C.W.W. Kannangara’s Handessa rural education scheme. (For an excellent account, see Gunasekara [2013].)

To Tagore, the school-society link was also necessary to impart moral virtues: “It is utterly futile to expect that the preaching of a few textbook precepts…at school will set right everything when countless varieties of dishonesty and perversity are destroying decency and taste every moment in today’s artificial life. This only results in different kinds of hypocrisy and insolent flippancy in the name of morality…”

All around us today, we can see how textbook-based teaching of virtues has led to hypocrisy among those who do wrong with impunity, flippancy among those who allow wrong to happen as if it is the norm, and cynicism among those who try to reconcile what they see with what they were taught in classrooms.

I am sure you will appreciate that some of Tagore’s humanistic ideas are being put into practice in pre-school and primary education even today, for instance following the teachings of Maria Montessori. In Sri Lanka, however, because of the bottleneck effect of exams, they are being throttled by the competitiveness and the rush to obtain certificates. This has enormous implications to our own education system. What Tagore taught us – by not judging learning through exams – is that if we had exams, much of what we expect students to learn would be ignored because they are not specifically assessed in the exams. The reason we want exams is because we want to compare student with student. But how can we compare student with student if each student is a unique person? What do we value greater: the comparison or the uniqueness? We must be careful when answering this question, because often it turns out that our answer is actually not that of the educationist but that of the industrialist, and not that of our society’s but that of the countries in the core of knowledge production.

Phase 2: ‘Freedom from ignorance and want’

This is perhaps the phase of his work that is hardest to pin down to a few fundamentals. But I will try.

To me, it appears that his first lesson is to tailor education to our own needs, rather than to import and transplant an educational system from elsewhere. (Tagore himself was, of course, warning about the dangers of blindly following the British system.) This is an excellent testament for what we today call contextual knowledge or conditional knowledge.

Looking around, I cannot help feel that this is such an important lesson for us too. I wish that as educationists we paid more attention to this. We cannot do so if we merely ask our teachers to do what international experts advise. We must study our own society, our own past practices and experiments, how they have succeeded or failed and why, what would work for us now and so on. Tagore said:

“Only when we are able to channel the current of education in our country through the numerous experiments of numerous teachers, it will become a natural thing of the country. Only then will we come across real teachers here and there, now and then. Only then a tradition, a succession of teachers will naturally follow. We cannot invent a particular educational system by labelling it as ‘national’. We can call ‘national’ only education of that kind which is being conducted in a variety of ways through a variety of endeavours by a variety of our countrymen…When a particular education system seeks to fasten a static ideal on to the country, we cannot call it ‘national’. It is communal and therefore, fatal to the country.”

To me, such a uniform education system is worse than communal – at best it would facilitate pedantry, at worst it could even facilitate totalitarianism and fascism.

Importantly, Tagore was keen to point out that when times change, the same energy needs to be spent on amending our systems and practices. In one speech he used a beautiful simile: he likened time to a river, and said that people who don’t change with changing times are like the people who would not change the position of the ferry even after the river has changed its position. He asked, How can they cross the river from the old ferry? This would be great advice for a country that still runs its educational system dictated to by policies that are over eighty years old.

The next crucial lesson is his trust in science and technology – but only appropriate technology – as well as his disdain for outdated traditions, superstitions and rituals. In this sense, he was remarkably modern. He said:

“When in the East we were busy calling upon the ghostbuster in case of disease, the astrologer to placate hostile planets in case of trouble, worshiping the goddess Sitala to ward off smallpox and similar epidemics, and practising home-grown black magic to get rid of enemies, in the West a woman asked Voltaire: ‘I have heard one can kill whole flocks of sheep by chanting a mantra?’ Voltaire replied: ‘It can certainly be done, but an adequate supply of arsenic along with it is also required.’ It cannot be absolutely ruled out that a modicum of faith in magic and the supernatural still persists in isolated pockets in Europe, but a trust in the efficacy of arsenic in this connection is almost universal there. That is why they can kill us whenever they want to and we are liable to die even when we do not want to.”

Tagore was wise enough to note that the British colonial government was actually quite keen to deny Indians this gift of science and technology. He pointed out that the colonial colleges and universities actually functioned with many constraints and limitations imposed by the colonial government. One of the main hopes that Tagore had in establishing Visva-Bharati was overcoming this. He knew that foreigners, both western and eastern, yearn to come to India to learn about her strong and vibrant achievements in the humanities. He welcomed them. In return, he also created space for Indians to come there and learn what the West had to teach – which, of course, was mainly science. This was the confluence of East and West that Tagore envisaged for Visva-Bharati. And I think that one

of the reasons why Visva-Bharati failed later on was that after Independence, India had an alternative, perhaps better way to forge ahead with science, when Jawaharlal Nehru set up the Indian Institutes of Technology. But I wonder whether Tagore’s plan in combining the strength in our humanities with the strength in science and technology of other lands within our educational system could still serve us here.

Tagore also created Sriniketan and its Institute of Rural Reconstruction, a rural upliftment

programme using what would later come to be called ‘appropriate technology’. This was not a

blind exercise in importing European machines and gadgets like washing machines or floor polishers. Instead, it was an attempt to solve the problems faced by the rural folk by the use of scientific knowledge and appropriate technological tools. It included components such as rural education, village sanitation, roving dispensaries, anti-malaria and child welfare schemes, cooperative societies, scientific

agriculture, experimental farming, dairy farming, weaving, tannery, smithy, carpentry and other

projects. It was designed to promote selfconfidence and self-help and eliminate ignorance and superstition among the villagers. As Tagore described his educational mission:

“Our centre of culture should not only be the centre of intellectual life of India, but the centre of her economic life as well. It must cultivate land, breed cattle, to feed itself and its students; it

must produce all necessaries, devising the best means and using the best materials, calling science to its aid. Its very success would depend on the success of its industrial ventures carried out on the co-operative principle; which will unite the teachers and students in a living and active bond of necessity. This will also give us a practical, industrial training, whose motive is not profit.”

When the time came for Tagore to send his son Rathindranath for higher education, he sent him not to Oxford but to learn agricultural science at Illinois: “Indians should learn to become better farmers in Illinois than better ‘gentlemen’ in Oxford”. Similarly, he sent the children of his relatives and friends, including his son-in-law, to learn other skills, such as scientific dairykeeping, the cooperative movement and rural medical systems.

We can see that Tagore’s educational philosophy was not merely bookish but also practical, not merely ideological but also pragmatic, not merely effective but also of quality, and not merely focused on the individual but also on uplifting the community. We can see that it was not pedantic but contextual, not blind but appropriate, and not profit-oriented but promoting human flourishing.

(To be concluded)

Opinion

Why so unbuddhist?

Hardly a week goes by, when someone in this country does not preach to us about the great, long lasting and noble nature of the culture of the Sinhala Buddhist people. Some Sundays, it is a Catholic priest that sings the virtues of Buddhist culture. Some eminent university professor, not necessarily Buddhist, almost weekly in this newspaper, extols the superiority of Buddhist values in our society. Some 70 percent of the population in this society, at Census, claim that they are Buddhist in religion. They are all capped by that loud statement in dhammacakka pavattana sutta, commonly believed to have been spoken by the Buddha to his five colleagues, when all of them were seeking release from unsatisfactory state of being:

‘….jati pi dukkha jara pi dukkha maranam pi dukkham yam pi…. sankittena…. ‘

If birth (‘jati’) is a matter of sorrow, why celebrate birth? Not just about 2,600 years ago but today, in distant port city Colombo? Why gaba perahara to celebrate conception? Why do bhikkhu, most prominent in this community, celebrate their 75th birthday on a grand scale? A commentator reported that the Buddha said (…ayam antima jati natthi idani punabbhavo – this is my last birth and there shall be no rebirth). They should rather contemplate on jati pi dukkha and anicca (subject to change) and seek nibbana, as they invariably admonish their listeners (savaka) to do several times a week. (Incidentally, Buddhists acquire knowledge by listening to bhanaka. Hence savaka and bhanaka.) The incongruity of bhikkhu who preach jati pi duklkha and then go to celebrate their 65th birthday is thunderous.

For all this, we are one of the most violent societies in the world: during the first 15 days of this year (2026), there has been more one murder a day, and just yesterday (13 February) a youngish lawyer and his wife were gunned down as they shopped in the neighbourhood of the Headquarters of the army. In 2022, the government of this country declared to the rest of the world that it could not pay back debt it owed to the rest of the world, mostly because those that governed us plundered the wealth of the governed. For more than two decades now, it has been a public secret that politicians, bureaucrats, policemen and school teachers, in varying degrees of culpability, plunder the wealth of people in this country. We have that information on the authority of a former President of the Republic. Politicians who held the highest level of responsibility in government, all Buddhist, not only plundered the wealth of its citizens but also transferred that wealth overseas for exclusive use by themselves and their progeny and the temporary use of the host nation. So much for the admonition, ‘raja bhavatu dhammiko’ (may the king-rulers- be righteous). It is not uncommon for politicians anywhere to lie occasionally but ours speak the truth only more parsimoniously than they spend the wealth they plundered from the public. The language spoken in parliament is so foul (parusa vaca) that galleries are closed to the public lest school children adopt that ‘unparliamentary’ language, ironically spoken in parliament. If someone parses the spoken and written word in our society, there is every likelihood that he would find that rumour (pisuna vaca) is the currency of the realm. Radio, television and electronic media have only created massive markets for lies (musa vada), rumour (pisuna vaca), foul language (parusa vaca) and idle chatter (samppampalapa). To assure yourself that this is true, listen, if you can bear with it, newscasts on television, sit in the gallery of Parliament or even read some latterday novels. There generally was much beauty in what Wickremasinghe, Munidasa, Tennakone, G. B. Senanayake, Sarachchandra and Amarasekara wrote. All that beauty has been buried with them. A vile pidgin thrives.

Although the fatuous chatter of politicians about financial and educational hubs in this country have wafted away leaving a foul smell, it has not taken long for this society to graduate into a narcotics hub. In 1975, there was the occasional ganja user and he was a marginal figure who in the evenings, faded into the dusk. Fifty years later, narcotics users are kingpins of crime, financiers and close friends of leading politicians and otherwise shakers and movers. Distilleries are among the most profitable enterprises and leading tax payers and defaulters in the country (Tax default 8 billion rupees as of 2026). There was at least one distillery owner who was a leading politician and a powerful minister in a long ruling government. Politicians in public office recruited and maintained the loyalty to the party by issuing recruits lucrative bar licences. Alcoholic drinks (sura pana) are a libation offered freely to gods that hold sway over voters. There are innuendos that strong men, not wholly lay, are not immune from seeking pleasures in alcohol. It is well known that many celibate religious leaders wallow in comfort on intricately carved ebony or satin wood furniture, on uccasayana, mahasayana, wearing robes made of comforting silk. They do not quite observe the precept to avoid seeking excessive pleasures (kamasukhallikanuyogo). These simple rules of ethical behaviour laid down in panca sila are so commonly denied in the everyday life of Buddhists in this country, that one wonders what guides them in that arduous journey, in samsara. I heard on TV a senior bhikkhu say that bhikkhu sangha strives to raise persons disciplined by panca sila. Evidently, they have failed.

So, it transpires that there is one Buddhism in the books and another in practice. Inquiries into the Buddhist writings are mainly the work of historians and into religion in practice, the work of sociologists and anthropologists. Many books have been written and many, many more speeches (bana) delivered on the religion in the books. However, very, very little is known about the religion daily practised. Yes, there are a few books and papers written in English by cultural anthropologists. Perhaps we know more about yakku natanava, yakun natanava than we know about Buddhism is practised in this country. There was an event in Colombo where some archaeological findings, identified as dhatu (relics), were exhibited. Festivals of that nature and on a grander scale are a monthly regular feature of popular Buddhism. How do they fit in with the religion in the books? Or does that not matter? Never the twain shall meet.

by Usvatte-aratchi

Opinion

Hippocratic oath and GMOA

Almost all government members of the GMOA (the Government Medical Officers’ Association). Before joining the GMOA Doctors must obtain registration with Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC) to practice medicine. This registration is obtained after completing the medical studies in Sri Lanka and completing internship.

The SLMC conducts an Examination for Registration to Practise Medicine in Sri Lanka (ERPM) – (Formerly Act 16 in conjunction with the University Grants Commission (UGC), which the foreign graduates must pass. Then only they can obtain registration with SLMC.

When obtaining registration there are a few steps to follow on the as stated in the “

GUIDELINES ON ETHICAL CONDUCT FOR MEDICAL & DENTAL PRACTITIONERS REGISTERED WITH THE SRI LANKA MEDICAL COUNCIL” This was approved in July 2009, and I believe is current at the time of writing this note. To practice medicine, one must obtain registration with the SLMC and complete the oath formality. For those interested in reading it on the web, the reference is as follows.

https://slmc.gov.lk/images/PDF_Main_Site/EthicalConduct2021-12.pdf

I checked this document to find the Hippocratic Oath details. They are noted on page 5. The pages 6 & 7 provide the draft oath form that every Doctor must complete with his/her details. Oath must be administered by

the Registrar/Asst. Registrar/President/ Vice President or Designated Member of the Sri Lanka Medical Council and signed by the Doctor.

Now I wish to quote the details of the oath.

I solemnly pledge myself to dedicate my life to the service of humanity;

The health of my patient will be my primary consideration and I will not use my profession for exploitation and abuse of my patient;

I will practice my profession with conscience, dignity, integrity and honesty;

I will respect the secrets which are confided in me, even after the patient has died;

I will give to my teachers the respect and gratitude, which is their due;

I will maintain by all the means in my power, the honour and noble traditions of the medical profession;

I will not permit considerations of religion, nationality, race, party politics, caste or social standing to intervene between my duty and my patient;

I wish to ask the GMOA officials, when they engage in strike action, whether they still comply with the oath or violate any part of the oath that even they themselves have taken when they obtained registration from the SLMC to practise medicine.

Hemal Perera

Opinion

Where nature dared judges hid

Dr. Lesego the Surgical Registrar from Lesotho who did the on-call shift with me that night in the sleepy London hospital said a lot more than what I wrote last time. I did not want to weaken the thrust of the last narrative which was a bellyful for the legal fraternity of south east Asia and Africa.

Lesego begins, voice steady and reflective, “You know… he said, in my father’s case, the land next to Maseru mayor’s sunflower oil mill was prime land. The mayor wanted it. My father refused to sell. That refusal set the stage for everything that followed.

Two families lived there under my dad’s kindness. First was a middle-aged man, whose descendants still remain. The other was an old destitute woman. My father gave her timber, wattle, cement, Cadjan, everything free, to build her hut. She lived peacefully for two years. Then having reconciled with her once estranged daughter wanted to leave.

She came to my father asking for money for the house. He said: ‘I gave you everything free. You lived there for two years completely free and benefitting from the produce too. And now you ask for money? Not a cent.’ In hindsight, that refusal was harsh. It opened the door for plunderers. The old lady ‘sold’ the hut to Pule, the mayor’s decoy. Soon, Pule and his fellow compatriots, were to chase my father away while he was supervising the harvesting of sunflowers.

My father went to court in September 1962, naming Thasoema, the mayor, his Chief clerk, and the trespassers as respondents. The injunction faltered for want of an affidavit, and under a degree of compulsion by the judge and the attending lawyers, my father agreed to an interim settlement of giving away the aggressors total possession with the proviso that they would pay the damages once the court culminates the case in his favour. This was the only practical alternative to sharing the possession with the adversaries.

From the very beginning, the dismissals and flimsy rulings bore the fingerprints of extra‑judicial mayoral influence. Judges leaned on technicalities, not justice. They hid behind minutiae.

Then nature intervened. Thasoema, the mayor, hale and hearty, died suddenly of what looked like choking on coconut sap which later turned out to be a heart attack. His son Teboho inherited the case. Months later, the Chief clerk also died of a massive heart attack, and his son took his place. Even Teboho, the mayor’s young son of 30 years died, during a routine appendectomy, when the breathing tube was wrongly placed in his gullet.

About fifteen years into the case, another blow fell. A 45‑year‑old judge, who had ruled that ‘prescription was obvious at a glance, while adverse possession was being contested in court all the time, died within weeks of his judgment, struck down by a massive heart attack.

After that, the case dragged on for decades, yo‑yoing between district and appeal courts. Judges no longer died untimely deaths, but the rulings continued to twist and delay. My father’s deeds were clear: the land bought by his brother in 1933, sold to him in 1936, uninterrupted possession for 26 years. Yet the courts delayed, twisted, and denied.

Finally, in 2006, the District Court ruled in his favour embodying every detail why it was delivering such a judgement. It was a comprehensive judgement which covered all areas in question. In 2015, the Appeal Court confirmed it, his job being easy because of the depth the DC judge had gone in to. But in October 2024, the Supreme Court gave an outrageously insane judgment against him. How? I do not know. I hope the judge is in good health, my friend said sarcastically.

Lesego paused, his voice heavy with irony “Where nature dared, judges hid. And that is the truth of my father’s case.”

Dr.M.M.Janapriya

UK

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction