Features

Reminiscences of my short stint in teaching

by HM Nissanka Warakaulle

In the late 1950s, the University of Ceylon authorities used to send a form to every undergraduate sitting the final examinations for those who were desirous of serving as teachers to furnish their personal details and mention two districts in order of preference, where they were willing to serve. Most undergraduates duly filled up the forms, and others were not interested in teaching. Most of us who wanted to get a teaching position not because we wanted to make teaching our career, but to mark time until we secured a job of our choice.

I finished my last paper on the 26 April 1962, and went home. Two days later, I got a letter from the Ministry of Education appointing me as a teacher at the Maha Vidyalaya in Dambulla with effect from 02 May, just six days after sitting the final examination! My first preference was Kandy District. I had mentioned Matale as my second preference not realising that the Matale District extended up to Sigirya. My neighbour, Tissa, had received the appointment to Holy Trinity College, Nuwara Eliya. He wanted me to accompany him to Nuwara Eliya to see how the school was. When we reached the school and met the Principal, Mr. Atapattu, I was happy to hear that he was an old boy from my own school, Kingswood College, Kandy. Tissa was happy and accepted the appointment.

On the afternoon of 01 May, I left home with a travelling bag filled with my clothes and linen and took a bus to Kandy and then a bus going to Anuradhapura. When the bus stopped at the halt near the Dambulla temple, I alighted from the bus and inquired from a person in a boutique for directions to get to the school. He gave the directions correctly and I wended my way to the school.

Before I proceed with my experiences in the school, I thought I should describe what Dambulla was at that time. There were only four permanent government buildings, namely, the hospital, police station, school and Rest House; and the small building for the circuit judge to hear the cases which were taken up monthly. The roads did not have any streetlamps and there was no pipe borne water. The well situated in close proximity to the school was the only available source of water for drinking, cooking, washing and bathing. As the well was a deep one we had to draw the water with a pail that was operated through a pulley tied onto a beam above the well. However, the water was brackish. Whenever I went to the school after dark, I had to carry a powerful torch to see whether there were any serpents on the roads.

The school was situated halfway on the road that connected the Kandy Road and the Kurunegala Road. When I reached the school and walked in, there were three men in sarong in an old building built with granite bricks. The building was partitioned into two sections. One section was the temporary hostel for the teachers and the other was occupied by the Public Works Department (PWD) Overseer. As I entered the premises, the three men were wondering who I was. I introduced myself and told them that I have been appointed as a teacher at that school. They introduced themselves to me as Jayasuriya the graduate Slnhala teacher (who had been a monk up to graduation), the second (who used to wear the national dress) and Wimalweera by name, as the Mathematics teacher and the third, Bandara as the teacher in charge of Music. Fortunately for me there was a bed with mattress and pillow and a net. The net was an important item in that area as there were tarantulas and other dangerous insects such as the centipedes, and serpents such as mapilas.

Having completed the preliminaries of introductions and accommodation, the three teachers told me about how the hostel was run. We had to pool and buy the requirements for the tea in the morning and afternoon. All three meals were provided by a woman who was known by the sobriquet “Buthamma” and this appellation had stuck with her for the rest of her life. I had no clue as to how hygienically the food was prepared. But then there was no alternative and from what I could fathom no one has had even a mild irritation in their abdomens, and of course, the food was palatable. I agreed to these, and the money was paid at the end of the month for the tea to Jayasuriya and to the “Bathamma” for the meals.

The following morning, I got ready and went to the school. The school comprised tow long buildings for the classes and a room for the Principal’s office. The Principal, Mr. Wickramaratne commuted daily by bus from home which was close to Matale. He used to wear the western attire, sans the tie. I introduced myself divulging the subjects I had done while reading for the degree at Peradeniya. I had been sent as a replacement to a lady teacher, Mrs. Alwis, who was going on transfer. That day she was also present, and it was a wonderful sight to see all the students who had studied English, Geography and Government going down on their knees and worshipping in appreciation of the work she had done as well as to bid adieu. We could see Mrs. Alwis’ eyes welled with tears at the way the students did it.

I was assigned to teach Geography, Government and English in the HSC (now Advance Level) class and English and Geography in the SSC class (now Ordinary Level). English was of course a cake walk. But the other two modules were real killers, especially Geography. I had done my degree in the English medium and now I had to teach in the Sinhala medium. I had to refer to the glossaries to get the equivalent of the English terms and prepare for the lessons. I did not study so hard even to sit the final examination at the university! Fortunately, I mastered it by the end of the first year and thereafter I had no problem.

I took up the teaching appointment at Dambulla thinking that I would be able to get to a school in or closer to Kandy. This was because the company in Dambulla was not that enjoyable, and I also missed my participation is sports activities. In my second year there were five teachers who came to Dambulla after finishing their training at Maharagama. They were Upali Nanayakkara, Vithanage and Benedict Fernando and two lady teachers of whom I remember the name of one, that is, Ms. Dharmaratne. A little later another graduate from Peradeniya, Premadasa joined the staff. Now it became a little more interesting. Though these young teachers were boarded in houses close to the school, on and off we used to meet to play some softball cricket on the playground opposite the school along with some of the boys of the school and other residents. We also used to go to the courts when in session to listen to the cases being heard. Once in a way we used to go to the Rest House to have a quiet drink(it was only Jubilee beer that we had) and have some fun at the expense of Premadasa, who never lost his temper though he was the butt end of all the jokes.

There was a Physical Training Instructor (PTI), Mr.Silva, who used to go to Kandy to play for the Education team in the tournament conducted by the Kandy District Cricket Association on duty leave. I told him that I too played cricket. I accompanied him to Kandy on a day a match was being played and he introduced me to the captain of the Education team, Balasooriya. I was included in the team thereafter and played in the team in all matches thereafter even after changing schools. Justin Perera and Henry Jayaweera from Talatuoya Central school (who later became my colleagues on the same staff) and Bertie Nillegoda who was a relative of mine and a teacher at St. Sylvesters College, Kandy (and later became the Principal of that school) were the others known to me. We really enjoyed meeting together more than playing in matches.

While at Dambulla a few of us went to Polonnaruwa to engage in a shramadana campaign to clear the roadway to the Somawathie stupa as there was no macadamized road to the chaitya at that time. The entire area surrounding the chaitya was a dense forest. We noticed there were footprints and dung of the wild elephants on the way to the chaitya. The other trip we made was to a village called Makulugaswewa off Galewela for the music teacher to record some folk songs by the villagers. The villagers were very obliging and rendered some of the folk songs they used to sing at functions like harvesting or transplanting of paddy.

The heartening news I heard later was that a few of the students I had taught had entered the university, graduated and had been successful in joining the Sri Lanka Administrative Service.

After having completed almost three years I requested a transfer to a school in Kandy. But the Principal used to always state that I could be released if replacement is given. Though his predicament was understandable I was not happy. So, I decided to go and meet the Director of Education at Kandy, Mr. Welagedera and told him that I must have a transfer to a school in Kandy or else I would have no alternative but to tender my resignation. He gave me a transfer to the Maha Vidyalaya in Ankumbura.

When I got the letter, I did not know where the school was located. After verifying the location, I embarked on the trip to the school on the first day of term. I had to take three buses to get to the school, that is, first from home to Kandy, then from Kandy to Alawathugoda and the third from Alawathugoda to Ankumbura. I can remember the Principal, a Mr. Abeyratne, a graduate teache, Mr. Ekanayake and the lady music teacher who was from the same school as the music teacher at Dambulla, namely Talatuoya Central. I had to get up at 4.00 am, have breakfast get ready and leave home. I felt bad more than for myself for my mother as she had to get up very early to get the meal ready. After school when I returned home it was about 3.00 pm and that was the time, I had my lunch. At the beginning of the next term two other graduates known to me at Peradeniya, Navaratne ( Koti Nava), and Lelwela and another graduate, also named Navaratne joined the staff. Koti Nava later joined the Ceylon Transport Board and Lelwela the Sri Lanka Export Development Board.

After two terms I thought enough was enough and went and met Mr. Shelton Ranaraja who was our MP and known to me and told him that I needed a transfer to a school close to home. He arranged a transfer to Talatuoya Central school. This school was just four miles from home, and I had to travel against the traffic as the buses from Kandy to Talatuoya were almost empty and it took me only half an hour to get to school. On the first day of term, I went and met the Principal, Mr. Gallela. He greeted me well and assigned me Geography in the HSC and SSC classes and English in some junior classes. Justin and Henry were there, and in addition Lal Wijenayake, who joined Peradeniya in my final year and who was in the same Hall with me, Mr. and Mrs. Silva (who came to school by car), Shelton Perera, who along with Lal joined the legal profession laterand practiced in Kandy.

Henry was training a football team with practices being held on a playground just a little bigger than a tennis court and with hardly any grass. I thought I too should do something to help the children and thought of starting hockey. The boys in that school had not seen a hockey stick leave alone a hockey match. I told the Principal what I had in mind, without expecting much support. However, I was taken aback when he agreed to release the money needed to buy all the equipment required for the purpose! I went ahead and purchased all the equipment from Chands, the sports good shop in Kandy at a discount.

I trained two teams, namely, the under 19 and under 17 teams, concentrating more on the latter as they would be playing for a longer time. Then to everybody’s surprise, the under 17 novices team beat the Nugawela Central college team, which had been playing hockey for some time. The Principal and the other members of the staff were very happy.

During the interval, Justin, Lal, Henry, Tudor, Mr. and Mrs. Silva, Shelton and myself would meet in Justin’s Laboratory to have a snack brought by one teacher and a cup of tea. We used to take turns to bring the snack to share. Of course, a few of us who used to smoke would enjoy a quick puff. It was a very good time that all of us had.

Tudor Dharmadasa, who was one year senior to me at Peradeniya, was also a teacher at Talatuoya and he was the teacher in charge of the hostel. The hostellers were provided with all three meals of the day. When I inquired from Tudor how much it costs to feed the boys, he told me that they were given funding at the rate of Rs. 3.00/- per student per day to cover all three meals! I was a bit surprised. But he assured me that there was no problem, and it was done to the satisfaction of all concerned. He wanted me to come one day and taste the lunch provided. I accepted the invitation and found the food quite good and palatable.

While at Talatuoya Central, Henry Jayaweera and I used to umpire school hockey matches in Kandy, Peradeniya and Gampola without any payment. Both of us enjoyed it. I also attended a one-week hockey coaching camp at Nuwara Eliya where I and my vice- captain at Peradeniya, SB Ekanayake were the coaches. The boys who followed the coaching had never played hockey before nor had they even seen a hockey match! But at the end of the camp most of them had mastered the art.

After teaching at Talatuoya for two terms, I received a letter from the Ceylon Transport Board (CTB) summoning me to appear for a viva voce at the CTB Head office in Narahenpita. I went on the designated day and faced the interview panel. The following week I received a letter from the CTB indicating that I had been selected and to assume duties on 16th June 1966. I informed the Principal, gave him the letter of resignation and bade farewell to the teachers of the tea club and left the school giving up teaching at last. Anyway, all in all, it was a happy ending as I really enjoyed teaching at Talatuoya Central school.

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

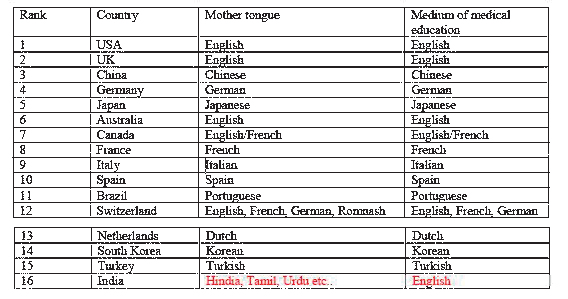

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

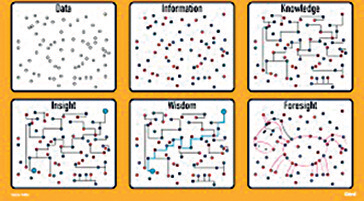

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

Features

Ukraine crisis continuing to highlight worsening ‘Global Disorder’

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

One fatal consequence of the foregoing trends is relentlessly increasing ‘Global Disorder’ and the heightening possibility of a regional war of the kind that broke out in Europe in the late thirties at the height of Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler’s reckless territorial expansions. Needless to say, that regional war led to the Second World War. As a result, sections of world opinion could not be faulted for believing that another World War is very much at hand unless peace making comes to the fore.

Interestingly, the outbreak of the Second World War coincided with the collapsing of the League of Nations, which was seen as ineffective in the task of fostering and maintaining world law and order and peace. Needless to say, the ‘League’ was supplanted by the UN and the question on the lips of the informed is whether the fate of the ‘League’ would also befall the UN in view of its perceived inability to command any authority worldwide, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine blood-letting.

The latter poser ought to remind the world that its future is gravely at risk, provided there is a consensus among the powers that matter to end the Ukraine crisis by peaceful means. The question also ought to remind the world of the urgency of restoring to the UN system its authority and effectiveness. The spectre of another World War could not be completely warded off unless this challenge is faced and resolved by the world community consensually and peacefully.

It defies comprehension as to why the Russian political leadership insists on prolonging the invasion, particularly considering the prohibitive human costs it is incurring for Russia. There is no sign of Ukraine caving-in to Russian pressure on the battle field and allowing Russia to have its own way and one wonders whether Ukraine is going the way of Afghanistan for Russia. If so the invasion is an abject failure.

The Russian political leadership would do well to go for a negotiated settlement and thereby ensure peace for the Russian people, Ukraine and the rest of Europe. By drawing on the services of the UN for this purpose, Russian political leaders would be restoring to the UN its dignity and rightful position in the affairs of the world.

Russia, meanwhile, would also do well not to depend too much on the Trump administration to find a negotiated end to the crisis. This is in view of the proved unreliability of the Trump government and the noted tendency of President Trump to change his mind on questions of the first importance far too frequently. Against this backdrop the UN would prove the more reliable partner to work with.

While there is no sign of Russia backing down, there are clearly no indications that going forward Russia’s invasion would render its final aims easily attainable either. Both NATO and the EU, for example, are making it amply clear that they would be staunchly standing by Ukraine. That is, Ukraine would be consistently armed and provided for in every relevant respect by these Western formations. Given these organizations’ continuing power it is difficult to see Ukraine being abandoned in the foreseeable future.

Accordingly, the Ukraine war would continue to painfully grind on piling misery on the Ukraine and Russian people. There is clearly nothing in this war worth speaking of for the two peoples concerned and it will be an action of the profoundest humanity for the Russian political leadership to engage in peace talks with its adversaries.

It will be in order for all countries to back a peaceful solution to the Ukraine nightmare considering that a continued commitment to the UN Charter would be in their best interests. On the question of sovereignty alone Ukraine’s rights have been grossly violated by Russia and it is obligatory on the part of every state that cherishes its sovereignty to back Ukraine to the hilt.

Barring a few, most states of the West could be expected to be supportive of Ukraine but the global South presents some complexities which get in the way of it standing by the side of Ukraine without reservations. One factor is economic dependence on Russia and in these instances countries’ national interests could outweigh other considerations on the issue of deciding between Ukraine and Russia. Needless to say, there is no easy way out of such dilemmas.

However, democracies of the South would have no choice but to place principle above self interest and throw in their lot with Ukraine if they are not to escape the charge of duplicity, double talk and double think. The rest of the South, and we have numerous political identities among them, would do well to come together, consult closely and consider as to how they could collectively work towards a peaceful and fair solution in Ukraine.

More broadly, crises such as that in Ukraine, need to be seen by the international community as a challenge to its humanity, since the essential identity of the human being as a peacemaker is being put to the test in these prolonged and dehumanizing wars. Accordingly, what is at stake basically is humankind’s fundamental identity or the continuation of civilization. Put simply, the choice is between humanity and barbarity.

The ‘Swing States’ of the South, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa and to a lesser extent Brazil, are obliged to put their ‘ best foot forward’ in these undertakings of a potentially historic nature. While the humanistic character of their mission needs to be highlighted most, the economic and material costs of these wasting wars, which are felt far and wide, need to be constantly focused on as well.

It is a time to protect humanity and the essential principles of democracy. It is when confronted by the magnitude and scale of these tasks that the vital importance of the UN could come to be appreciated by human kind. This is primarily on account of the multi-dimensional operations of the UN. The latter would prove an ideal companion of the South if and when it plays the role of a true peace maker.

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation